Abstract

Hypertension (HTN) is a highly prevalent risk factor for cardiovascular (CV), cerebrovascular, and renal diseases and disproportionately affects African Americans (AAs). It has been shown that promoting the adoption of healthy lifestyles, ones that involve best practices of diet and exercise and abundant expert support, can, in a healthcare setting, reduce the incidence of hypertension in those who are at high risk. In this paper, we will examine whether similar programs are effective in the AA church-community-based participatory research settings, outside of the healthcare arena. If successful, these church-based approaches may be applied successfully to reduce the incidence and consequences of hypertension in large communities with potentially huge impact on public health.

1. Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) is one of the most common diseases facing the American public today with elevated blood pressure (BP) representing the number 1 attributable risk for death worldwide [1–3]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data indicate that the age-standardized prevalence of HTN increased from 24.4% to 28.9% (P < .001) between surveys conducted in 1989–1991 and 1999–2004 [4]. An aging population, growing rates of obesity, high-sodium diets, and a sedentary lifestyle all are thought to contribute to this increase [5]. Nationally, HTN is the largest treatable contributor to stroke and the second largest contributor to coronary artery disease (CAD). It is also the second leading cause of end-stage renal disease and contributes significantly to congestive heart failure [6]. HTN increases the risk of stroke, heart attack, heart failure, and kidney disease [1, 3], and though it is a modifiable risk factor for all the aforementioned diseases, however, no significant change in HTN prevalence is seen from 1999 to 2006 [7, 8]. In 2005-2006, approximately 29% of the US population over the age of 18 was hypertensive (almost equal prevalence between male and female), with the definition of HTN being systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mm Hg, or taking medications for HTN [3, 7, 8].

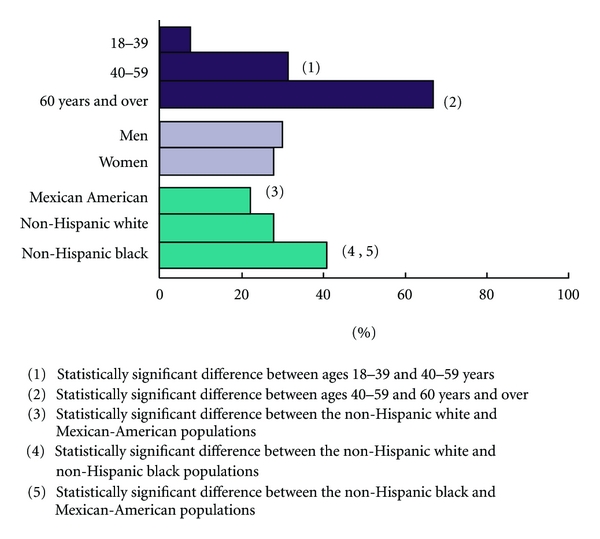

The prevalence of HTN increased with age from 7% among those aged 18–39 years to 67% among those aged 60 years and older [7]. Furthermore, during this time period, pre-HTN, defined as SBP between 120–139 mm Hg and DBP between 80–89 mm Hg emerged as is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [9] and is associated with an increase in all-cause and CV mortality [10–14]. Currently an estimated 37% of adult Americans have pre-HTN, including 41,900,000 men and 27,800,000 women [14, 15]. People with pre-HTN are more likely to have obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and type 2 diabetes than those without it [16]. Pre-HTN is associated with a decreased life expectancy, increased hospitalizations, and increased health care costs and serves as a precursor to HTN [17–19].

In African Americans (AAs), HTN is more common, more severe, develops at an earlier age, and leads to more clinical sequelae than in age-matched non-Hispanic whites (Figure 1) [3, 6]. As a result, among hypertensive AAs, the stroke mortality rate is 80% higher, CAD mortality rate is 50% higher, and HTN-related end-stage renal disease rate is 320% higher than for the general population [7]. This high-CVD-risk group, hypertensive AAs, now totals greater than 9 million American adults, and with the increasing age, health disparities, and weight of society as a whole, this number will continue to rise [2, 7]. The objective of this paper is to provide review of hypertension control programs focusing on life style and diet modifications. In addition, we also provide details on DASH (dietary approaches to stop hypertension) diet program and its implication in the community settings.

Figure 1.

Age-specific and age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in adults: United States, 2005-2006.

2. Role of Diet and Lifestyle Modification in HTN Prevention and Treatment

The magnitude of HTN, including pre-HTN, in terms of population size, the severe consequences of uncontrolled HTN, and the personal and economic costs to individuals and to the nation's health care system demand that national nutrition policy regarding HTN management promote strategies that have been proven to be effective, safe, and feasible. Such approaches are typically associated with concomitant benefits such as extended life expectancy, enhanced quality of life, and improvements in multiple risk factors. Joint National Committee-7 (JNC-7) guidelines direct physicians to prescribe lifestyle modification to all patients with BP classified as pre-HTN or greater [8]. The recommendations for lifestyle treatment include losing weight if overweight, reducing sodium intake, increasing physical activity, limiting alcohol intake, and eating a healthy dietary pattern such as the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) pattern [20–24]. The successful NIH-funded DASH feeding study (details below) showed greater improvement in BP (greater effect in AAs than other groups) than a diet high in fruits and vegetables only [20]. Moreover, adherence to the DASH-style diet is associated with a lower risk of CAD, stroke and recently showed lowering in the incidence of heart failure [25–27]. Subsequently, the DASH-Sodium trial (details below) found that additional sodium restriction resulted in even greater BP reduction [27–31]. The DASH diet has also been shown to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels [23]. The DASH diet is now widely promoted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) for the prevention and treatment of hypertension [8] and is included as an example of a healthy eating pattern in the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [32].

Ideally, this dietary pattern would be a key intervention for AA with HTN. As >10 years of accumulateddata have now proven, the dietary pattern exemplified by the DASH diet meets all of these criteria, particularly for AA, and is the obvious ‘‘best practice” among dietary modifications for reducing HTN and CVD risk in this population. In the original efficacy study of DASH, the effect on BP of the DASH diet was more pronounced in AA participants as compared to white participants (6.8 versus 3 mm Hg, P < .05) [21]. The subsequent clinic-based community trial called PREMIER (details below) tested the DASH dietary pattern plus established lifestyle modifications for BP control [33–39]. In PREMIER study, the DASH dietary pattern plus established lifestyle recommendations decreased BP by 4.3 mm Hg, whereas an advice only intervention group had a reduction of 2.6 mm Hg only (P < .001) [30–33]. However, the impact of the established plus DASH intervention in AA was less than what might be expected given prior efficacy studies. This was particularly true for AA women, where there was no significant difference in BP reduction compared to the advice-only intervention [33–36, 39].

3. Community-Based Health Promotion (CBHP) Programs

Enough available clinical evidence suggests that DASH diet [20–22] with intensive lifestyle modification (PREMIER)—is an effective preventive intervention for HTN prevention and treatment [8, 20–22, 33–39]. Delivery of these lifestyle interventions through CBHP programs has emerged as the important next step [40–43]. For example, during the past decade numerous intervention studies have shown the ability of small portions of lifestyle programs to reduce risk factors for CVD in both clinical and community settings [12, 40–46], and several frameworks for evaluating these CBHP programs have been proposed [41]. Churches and other faith-based organizations have, for a number of reasons, become increasingly popular settings in which to conduct health promotion programs and research studies [47–51]. Most AAs attend church or other organized religious venues, making these settings ideal for reaching and recruiting potential participants for public health programs. The historical Bible belt also continues to thrive; data for states such as Missouri and Kansas indicate that >90% of adults (majority of AAs) report some religious affiliation [47]. Also, the number of “mega-churches” (churches with ≥2000 members), is increasing nationally, with ~1200 mega-churches listed in 2005 by the Faith Communities Today Project [51, 52]. Faith-based settings are good for effectiveness trials, because AAs are more likely to identify themselves as being religious [47].

There are still other reasons to use church settings to conduct health promotion programs. Religious affiliation and church attendance improve physical and psychological health across religions and populations worldwide [37, 38]. Many religious organizations include health as part of their mission or ministry and often create health committees and participate in community outreach activities such as soup kitchens. Churches also provide an attractive venue to recruit and retain participants, because they tend to be stable institutions with members who attend church activities frequently over many years. The purpose of holding CBHP programs in churches is to reduce health disparities, especially in AAs [38, 39] which is consistent with the mission of AA churches to contribute to the social, economic, and political welfare of their congregants, and to the community at large [50, 51].

Nevertheless, CBHPs, even church-affiliated ones, face obstacles. One is that many of today's chronic diseases, including HTN, are complex and have multiple contributing risk factors. Hence, health promotion programs that address the multilevel nature of chronic diseases are also more complex and more difficult to conceptualize and implement. But they are also more likely to cause lasting behavioral changes [51], especially if the affiliation is strong. For example, church-affiliated CBHP programs can be classified into 1 of 3 categories: faith-based, faith-placed, and collaborative [52]. Faith-based programs emanate from existing committees or groups within the church (e.g., health ministries). Faith-placed programs work with churches, but originate outside the church [51]. Collaborative programs include partnerships between churches and outside groups. A literature review on church-affiliated CBHP programs from 1990 to 2005 showed that ~25% of programs are faith-based, 40% are faith-placed, and 35% are collaborative [41]. The later programs, collaborative partnerships, were particularly recommended for efforts that are meant to be evaluated and their findings disseminated and were found to be more effective than the other two. This current project is developed as collaborative community-based participatory research (CBPR) health promotion faith-based program in 16 AA churches.

4. Health Disparities Related to HTN

AAs have a disproportionately higher incidence of HTN, but are less likely to benefit from clinical lifestyle modification program. Although behavior modification is an important step in the management of HTN, AA have consistently been less successful at achieving behavior modifications, as seen in PREMIER, Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOPH), and the Hypertension Prevention Trial [33–39, 53, 54]. Despite clear efficacy, as in the DASH example, effectiveness has been difficult to achieve. This has been attributed to social and cultural barriers [55, 56] including different body-image ideals and food attitudes, to having fewer models for PA, and to normative views of overweight and obesity [55]. Thus, to successfully address health disparities, multiple sociocultural factors need to be addressed. Recruitment of participants into research is particularly challenging when working with AA or other racial/ethnic minority groups that traditionally have not been well served by health programs or research. Thus, an initial and vitally important step in recruiting participants is the establishment of trust and credibility within the AA community. Moreover, a church-affiliated, CBHP approach offers a way to make programs culturally appropriate by involving them in the development and implementation of these programs [57, 58]. Such programs can (a) foster dialogue and partnership to improve community health and (b) integrate the strengths and insights of all partners to address health disparities in a powerful way [48]. Fit body and Soul diabetes prevention program and HEALS (Healthy Eating and Living Spiritually) hypertension control program are some examples of strong community partnership and successful CBHP programs [59–61].

“Participatory Action Research” involves collaboration of the community and the researchers as colearners, and may be particularly suited to strategies for primary prevention of HTN in well-defined communities [62, 63]. These approaches tend to be highly valued by local communities because they can ensure the cultural relevance and appropriateness of interventions. To evaluate current evidence for the effectiveness of such an approach, we reviewed two types of studies: (a) recent studies that adapted lifestyle interventions using a CBPR approach in AA churches (Table 1) and (b) a few reports from community based trials that focused on DASH or DASH lifestyle program for HTN prevention and treatment (Table 2) in AA or other community settings.

Table 1.

Church-based participatory research interventions through African American churches.

| Study (ref) | Design | Outcomes | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Joy [64] n = 529 AA women from 16 churches | Randomization at church level-1-year followup | SBP, body weight, waist circumference, dietary energy and total fat, sodium intake | Spiritually based, behavior modification, program or self-help behavior modification | Intervention group improved: SBP (−1.6 mm Hg), weight loss (−1.1 lbs), waist circumference (−0.66 inches), dietary energy (−177 kcal), dietary total fat (−8 g), sodium intake (−145 mg) No change in self-help group |

| Baltimore Church High Blood Pressure Program (CHBPP) [54, 55] n = 187, 184 AA and 3 white women from black churches in Baltimore, MD | Randomized into those taking anti-hypertensive's than those without −8 wk counseling and exercising session −2 years | BP and body weight | Church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among black women: eight weekly 2-h diet counseling/exercise sessions. | Final SBP was <140 mm Hg for 74% of participants, versus 52% initially. Final DBP was <90 mm Hg in 92% versus 65% initially Mean weight loss was 6 lb in both groups: −18 to +7 lb in the Rx group and −31 to +3 lb in the no Rx group |

| Church-based education [56]. An outreach program for African Americans with hypertension N = 97 from AA churches | Outreach demonstration study | Knowledge, social support and BP | Registered nurses (RNs) were trained as church health educators The intervention's content included the bases of HTN and HTN management strategies, and was taught in eight 1-hr sessions. | Significant increase in knowledge scores from pre to post1 and post2. Education, age and number of years with high BP explained 49% of the variance associated with high BP knowledge. SBP/DBP and mean arterial BP significantly decreased from pre to post1 and post2 relationships were found between social support and DBP, and social support and mean arterial BP |

| Lighten Up: a church-based lifestyle program [57, 58] n = 381, 66% AA and 83% women | Partnership with christian church communities | BP and weight church counselors with experts were interventionists. | Total 10 wks-8 educational sessions, combining study of scripture and health messages, followup at 10 weeks and 1-yr. | Significant reductions in BP and weight (at 10 wks), which sustained throughout the year. 70% participants attended 50% or more sessions. Whites had greater reductions in risk factors than did AA |

| Church-based Cholesterol Education Program [70, 71] N = 348 from six churches with predominantly black members | Randomization at church level −6 months | Cholesterol and BP reduction | 6-week nutrition education class of 1 hour each week about techniques to lower blood cholesterol and BP. Information about cholesterol was also mailed to them. Church members selected as educationalists | Significant difference in the mean SBP was seen; 137.4 ± 22 SD for education group and 129.5 ± 18 SD for usual care group (P < .001) Education group had 23.4 mg per dl decrease in the mean cholesterol level |

HTN: hypertension; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; Rx: treatment; SD: standard deviation, wk: week; hr: hour.

Table 2.

Population-based DASH interventions to prevent or treat HTN in AA adults.

| Study (ref) | Study design and duration | Interventions/outcome | Community involvement and culturally relevant components | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appel et al. PREMIER trial [33–39, 70] | Multicenter randomized-controlled trial: 18 months. | Three arms; (a) advice only, (b) comprehensive lifestyle intervention, and (c) comprehensive lifestyle intervention plus DASH diet. Established guidelines from JNC V (weight loss, limited sodium and alcohol intake, and increased physical activity | N = 810 diverse participants from 4 clinical centers across the US communities among free living US adults. Healthy men and women age ≥25 years with high-normal BP (SBP = 130–139, DBP = 85–89) or stage 1 HTN (SBP = 140–159, DBP = 90–99) but not taking BP medication | The prevalence of HTN decreased from a baseline of 38% to 17% in the established group (P = .01) and to 12% in the established plus DASH group (P < .001) compared with a decrease to 26% in the advice-only group. Less reduction in AA as compare to other groups |

| Rankins et al. DASH dinners for AA [44, 75] | Neighborhood health care center for study enrollment | 1-2 hr weekly intervention × 8 wks. program included BP and weight monitoring brief nutrition education, meal service, recipe demonstrations, and taste-testing | N = 82 AA hypertensives list was obtained from medical records and recruited from AA communities. Dinners were based on DASH diet plan | BP was significantly lowered (P < .05) among participants who missed no more than 2 of 8 sessions |

| Bavikati VV [88] Effect of comprehensive therapeutic lifestyle changes on pre-HTN. | Community-based program of therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) for 6-months | TLC included exercise training, nutrition, weight management, stress management, and smoking cessation interventions | N = 2,478 ethnically diverse (AA n = 448, Caucasians n = 1,881) men (n = 666) and women (n = 1,812) with pre-HTN | SBP of 120 to 139 mm Hg (n = 2,082), decreased by 7 ±12 mm Hg (P = .001). DBP of 80 to 89 mm Hg (n = 1,504), decreased by 6 ±3 mm Hg (P = .001). No racial differences in BP reduction; women had greater BP reductions than men (P = .001) |

| Moore et al. [76] | 12 months Internet-based nutrition education program | DASH for Health program to provide weekly articles about healthy nutrition via the Internet. Dietary advice was based on the DASH diet | N = 2,834 corporation employees and their families. Outcome measures were weight and BP reduction and lifestyle modification | In 26% who were remained in the study in the study, weight change at 12 months was −4.2 lbs, SBP fell 6.8 mm Hg at 12 months, DBP 2.1 mm Hg. On self-entered food surveys, (n = 181) at 12 months were eating significantly more fruits, more vegetables, and fewer grain products |

| Bertoni et al. (Un-published) | Randomized: 3 months | Intervention: 8 group and 2 individual sessions and emphasize the adoption of DASH diet pattern at breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, both at home and when dining out Control: standard DASH and high blood pressure informational handouts |

Adoption of DASH eating pattern by African American adults with hypertension and prehypertension living in lower-income minority community | Results not available yet |

| Ard et al. [89] | Randomized: 4 years | Behavioral: DASH diet Behavioral: Intervention with no dietary component info |

Develop modified DASH dietary pattern that is culturally appropriate for African-Americans | Study in progress, and results not yet available |

5. Church-Based Behavioral Lifestyle

To generate Table, we identified a total of 76 studies published in 1990 or later using several web-based search engines (pub-med, midline, Cochrane, etc.). We closely examined only those (n = 5) that reported using a CBHP/CBPR or behavioral lifestyle intervention with BP as one of the outcome measures in the setting of an AA church. Some were led by church members and pastors, others by experts. They were conducted in a variety of geographic areas with sample sizes ranging from 39 to 251 [54–58, 64–71]. As shown in Table 1, a variety of health promotion and behavioral intervention strategies and techniques were shown to be effective at changing SIMPLE health behaviors of church members. Only a few were designed to rigorously test one strategy versus another or in combination with another [64, 65]. Outcomes varied and included BP reduction [54–58, 64, 70, 71], dietary change [54–56, 64–71], improved physical activity [65, 66], and weight loss [54–58, 64–69].

We found that certain overarching themes and core elements were necessary for CBHP programs to be implemented at any level (i) Some used church member volunteers as lay advisors/facilitators/peer educators to deliver intervention activities [64, 70, 71]. (ii) Some used registered nurses as interventionists [67]. (iii) The majority provided self-help materials that were culturally appropriate and/or individually tailored [54–58, 64–68, 70, 71]. (iv) Some included telephone counseling [65, 66]. These studies demonstrate that CBHP approaches can be effective in achieving simple health behavior changes in real world settings. However, none of these church-based studies used DASH diet with primary objective of prevention and treating HTN. Although several of these studies provide an effective model for partnering with AA churches [64–69], many were not successful in demonstrating significant lifestyle behavioral (BP, weight loss, and physical activity) changes [53, 64, 65]. Likely reasons for this include the fact that a proven lifestyle program was not used, the commitment of lay health counselors may not have been enough to sustain the program, and the interventions were led by church members without continuous support of experts [64]. Similarly, many other studies listed in Table 1 used similar approaches in their CBHP programs, which led to increased empowerment and community ownership of the health promotion program, and thus greater participation. However, several did not include a control group [65–69] and did not specify any theoretical framework. In some studies, change was evaluated only by self-report measures [64]. Also, long-term sustainability was generally not assessed or reported [65–67, 70, 71]. Thus, there is a dearth of literature on successful behavioral lifestyle programs with primary focus on HTN control in AA church settings. Last, many of these programs did not have an expert and church health counselor team working together as program interventionists (that we bring in this project), and this is one reason for the nonsustainability of the programs and for the limited commitment by church members [72, 73]. Also, none of these behavioral lifestyle programs were tailored towards reducing future risk of HTN in AA communities.

6. Community-Based Lifestyle Interventions Using DASH for HTN Control and Prevention

Some recent and relevant community interventions targeted toward HTN are shown in Table 2 [33–39, 44, 74]. These include targeted populations known to be at higher risk for HTN and CVD compared to the US population at large. Many included comparison groups. PREMIER trial (Table 2, Row 1) details given below showed the effectiveness of DASH plus lifestyle measures in free living adults in a clinical setting and in diverse and in an indigenous population [33–39, 74]. A small pilot CBPR study (Table 2, Row 2) was designed as a university-neighborhood health care center intervention to produce soul foods (DASH dinners) that met the nutrient criteria of the DASH diet plan [44, 75]. In this study, participants were low-income AA adults (N = 82) with poorly controlled BP. Six groups, each consisting of 12 to 15 participants taking antihypertensive medications, met for 1 to 2 hours per week for 8 weeks [44]. The intervention followed constructs of social cognitive theory and featured dinners based on the DASH diet plan. BP was significantly lowered (P < .05) among participants who missed no more than 2 of 8 sessions [44]. The DASH soul study was also developed following the same principles of the DASH diet, but targeting AA women with metabolic syndrome [75]. Though participants achieved goals, the sample was small, the duration was short, and sustainability of the program was not measured [44].

A similar study among corporation employees and families was conducted where nutrition advice based on the DASH diet was provided over the internet (Table 2, Row 4-Appendix A) [76]. This single-armed study was followed for 12 months and showed weight and BP reduction, but only 26% percent of total study subjects were retained at the end of 12 months, and AA were not significantly represented in this study (only 2%) [76].

Limitations of the above-mentioned studies include short intervention durations, large numbers of non-responders, and inability to link self-reported lifestyle changes to health outcomes/indicators. Few studies included AA communities [76] or showed positive outcomes for all intermediate outcomes of interest (e.g., healthy eating behaviors and increased PA). Further, few studies assessed whether the interventions were effective among target populations in reducing and sustaining lower or other risk factors for HTN. Finally, except one [44], none of these approaches were conducted in church-based or other faith-based settings.

Among published studies, most were done in populations with a disproportionately high incidence/prevalence of HTN, with their communities either initiating the study or collaborating with researchers. This finding is important and likely reflects the concern of leaders from these communities about HTN. Many researchers and collaborating communities are now breaking ground by implementing culturally relevant prevention programs in settings where many socioeconomic and environmental challenges exist. Although recent clinical trials have shown that DASH diet with lifestyle modification can prevent and treat HTN as well as delay the development of HTN [8, 20–22, 33–36], many of these clinical trials were conducted in resource-intensive clinical settings. There are few church-affiliated studies or programs led by church-based educators and counselors and supported by experts. We hereby present brief overview of DASH, DASH-sodium, and PREMIER studies.

7. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH Study)

The DASH study, sponsored by the National Institutes of health (NIH), was a highly successful, multicenter controlled, outpatient feeding study that assessed the efficacy of three separate diet plans for 8 weeks in diverse study population [8, 20–22, 77]. The trial enrolled 459 adults with SBP of less than 160 mm Hg and DBP of 80–95 mm Hg. The three eating plans were (a) one that includes foods similar to what many Americans regularly eat, (b) a plan that includes foods similar to what many Americans regularly eat plus more fruits and vegetables, and (c) the DASH eating plan. A typical DASH diet includes fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts, only small amounts of red meat, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages, and it contains decreased amounts of total and saturated fat and cholesterol (Table 3). The results were convincing. Subjects enrolled in both the plan that included more fruits and vegetables and the DASH eating plan had reduced BP, and DASH eating plan was more effective in reducing BP especially for those who had higher BP [20–22, 77]. The DASH diet lowered SBP by 5.5 mm Hg and DBP by 3 mm Hg over the control diet. DASH diet plan lowered BP substantially both in people with HTN and those without HTN, as compared to controlled typical diet in the US. The DASH diet was proven to reduce HTN, and the effect was greatest for AA, who showed higher BP reductions on the DASH diet as compared to other ethnic groups [77]. However, lower adherence to DASH diet in AA communities was seen that was attributable to mainly due to sociocultural reasons [78]. DASH now is recommended in national guidelines [8, 79, 80].

Table 3.

Dash eating plan.

| Food group | Daily servings | Serving sizes |

|---|---|---|

| Grains* | 6–8 | 1 slice bread |

| 1 oz dry cereal† | ||

| 1/2 cup cooked rice, pasta, or cereal | ||

| Vegetables | 4-5 | 1 cup raw leafy vegetable |

| 1/2 cup cut-up raw or cooked vegetable | ||

| 1/2 cup vegetable juice | ||

| Fruits | 4-5 | 1 medium fruit |

| 1/4 cup dried fruit | ||

| 1/2 cup fresh, frozen, or canned fruit | ||

| 1/2 cup fruit juice | ||

| Fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products | 2-3 | 1 cup milk or yogurt 1.5 oz cheese |

| Lean meats, poultry, and fish | 6 or less | 1 oz cooked meats, poultry, or fish 1 egg |

| Nuts, seeds, and legumes | 4-5 per week | 1/3 cup or 1.5 oz nuts 2 Tbsp peanut butter |

| 2 Tbsp or 1/2 oz seeds | ||

| 1/2 cup cooked legumes (dry beans and peas) | ||

| Fats and oils | 2-3 | 1 tsp soft margarine |

| 1 tsp vegetable oil | ||

| 1 Tbsp mayonnaise | ||

| 2 Tbsp salad dressing | ||

| Sweets and added sugars | 5 or less per week | 1 Tbsp sugar 1 Tbsp jelly or jam |

| 1/2 cup sorbet, gelatin | ||

| 1 cup lemonade | ||

*Whole grains are recommended for most grain servings as a good source of fiber and nutrients.

†Serving sizes vary between 1/2 cup and 1.25 cups, depending on cereal type. Check the product's nutrition facts label.

8. DASH-Sodium Study

Reducing the sodium chloride content of typical diets in the US lowers BP [81, 82], and guidelines recommend reducing the daily dietary sodium (Na) intake to 100 mmol (equivalent to 2.3 g of sodiumor 5.8 g of sodium chloride) or less [8]. DASH-Sodium trial studied the effect of different levels of dietary sodium, in conjunction with the DASH diet. DASH-Sodium trial studied the effect of different levels of dietary sodium, in conjunction with the DASH diet [28–30]. In a multicenter, randomized trial design, 412 participants were randomly assigned to eat either a control diet typical of intake in the US or the DASH diet. Within the assigned diet, participants ate foods with high (a target of 150 mmol per day with an energy intake of 2100 kcal), intermediate (a target of 100 mmol per day, reflecting the upper limit of the current national recommendations) and low (a target of 50 mmol per day, reflecting a level that we hypothesized might produce an additional lowering of BP) levels of sodium for 30 consecutive days each, in random order. The study showed that reducing the sodium intake from the high to the intermediate level reduced the SBP significantly by 2.1 mm Hg during the control diet and by 1.3 mm Hg during the DASH diet. Furthermore, reducing the sodium intake from the intermediate to the low level caused additional reductions of 4.6 mm Hg during the control diet and 1.7 mm Hg during the DASH diet. The effects of sodium were observed in participants with and in those without hypertension, AAs and those of other races, and women and men [28–30]. The DASH-Sodium study was the basis for PREMIER study described below.

9. The PREMIER Trial

The PREMIER study was conducted among 810 diverse participants from 4 clinical centers across the US [33–39, 74]. It established the effectiveness of a multifaceted behavioral intervention incorporating the efficacious DASH diet [8] among free-living US adults. This 18-months study consisted of 3 arms: (1) an “advice only” comparison group, (2) a behavioral intervention, termed “established” traditional lifestyle recommendations [79], and (3) a behavioral intervention, termed “established plus DASH” that implemented the same traditional recommendations plus the DASH diet [80]. During the first 12 weeks, there were 8 group sessions, one each week for 4 weeks, followed by a 2-week break during which individual sessions were held, then another group each week during weeks 7 through 10. There was another 2-week break for another individual visit. From weeks 13 through 24, another 6 group sessions were held (bringing the total to 14 group sessions). From months 7 until 18, the groups met monthly (bringing the total number of group sessions to 26), with individual sessions held quarterly. Each session included a topic on nutrition, PA and a behavior strategy, as well as a tasting experience focused on DASH related foods (or low fat foods for the non-DASH established arm) [33, 34]. There were significant weight changes between the comparison arm and behavioral arms at 6 months (mean change −1.1 kg versus −4.9 kg versus −5.8 kg, resp., P < .001 for difference between behavioral arms versus comparison, P = .07 for difference between behavioral arms). There were significant BP changes between behavioral arms versus the comparison at 6 months. Among all participants, there was a mean SBP change of −3.7 mm Hg between the behavioral only arm versus comparison (P < .001), a mean SBP change of −4.3 mm Hg between the behavioral plus DASH arm versus comparison (P < .001). There was not a significant BP change between the behavioral arms at 6 months. However, when DASH was translated with lifestyle modifications in this PREMIER study, only modest BP lowering benefit were seen in AA and no immediate benefit was seen AA women, in particular [28, 29]. However, though AA women were hardest to lose weight, effect was seen eventually.

10. Economics of Altering Dietary Behavior

Food availability and the cost of healthier food options has been the subject of a fair bit of research in recent years. Briefly, studies have demonstrated that actual and perceived food availability, prices, and quality differ by type of retail outlet, geographic location, and socioeconomic status. In turn, segments of the population, for example, inner city AAs, face potential barriers to high-quality dietary nutrients [81–87]. Most of these studies have analyzed environments using cross-sectional survey methods or secondary data sets making their results difficult to interpret with respect to individuals' behaviors. In addition, many studies were limited to particular urban areas and homogeneous socioeconomic groups.

11. Conclusion and Future Recommendations

Despite more than 30 years of intense activity to improve control—and more recently prevention—high BP continues to be a major public health problem. Since the 1970s, community-based programs have been instrumental in raising awareness, increasing knowledge, and promoting changes in health behavior to improve blood pressure control. Faith-based initiatives for lifestyle change show promise in helping to promote healthy behaviors in AA communities. AA individuals are more likely to attend faith-based services than Whites from similar backgrounds. Because of their disproportionately greater risk of HTN, AAs are a logical target for high-risk research and AA churches make an ideal setting for such programs. While faith- and community-based strategies are getting more attention from policy makers, further research on the effect of faith- and other community-based strategies is needed to understand how to improve health and health care practices among patients who are often locked out of the traditional health care system. Lifestyle programs that have been used in clinic settings can be translated to a faith-based setting. Published reports of applications of the DASH or PREMIER lifestyle intervention in community-based church settings are generally lacking. Additional research is needed and this is a promising area for further research.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the University of Kansas Medical Center, Department of Internal medicine for their full support with the HEALS project.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2007;56(5):1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Health, United States, 2007 with chart book on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, Md, USA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(2):199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):818–827. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostchega Y, Yoon SS, Hughes J, Louis T. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control—continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005-2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2008;(3):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. May 2010, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7. [PubMed]

- 9.Liszka HA, Mainous AG, III, King DE, Everett CJ, Egan BM. Prehypertension and cardiovascular morbidity. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(4):294–299. doi: 10.1370/afm.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AI, Suri MFK, Kirmani JF, Divani AA, Mohammad Y. Is prehypertension a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases? Stroke. 2005;36(9):1859–1863. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177495.45580.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainous AG, III, Everett CJ, Liszka H, King DE, Egan BM. Prehypertension and mortality in a nationally representative cohort. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(12):1496–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kshirsagar AV, Carpenter M, Bang H, Wyatt SB, Colindres RE. Blood pressure usually considered normal is associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Lee ET, Devereux RB, et al. Prehypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease risk in a population-based sample: the strong heart study. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):410–414. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205119.19804.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2008 update: a report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25–e46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Kirmani JF, Divani AA. Prevalence and trends of prehypertension and hypertension in United States: national health and nutrition examination surveys 1976 to 2000. Medical Science Monitor. 2005;11(9):CR403–CR409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenlund KJ, Croft JB, Mensah GA. Prevalence of heart disease and stroke risk factors in persons with prehypertension in the United States, 1999–2000. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(19):2113–2118. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco OH, Peeters A, Bonneux L, de Laet C. Blood pressure in adulthood and life expectancy with cardiovascular disease in men and women: life course analysis. Hypertension. 2005;46(2):280–286. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000173433.67426.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(18):1291–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell LB, Valiyeva E, Carson JL. Effects of prehypertension on admissions and deaths: a simulation. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(19):2119–2124. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogt TM, Appel LJ, Obarzanek E, et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension: rationale, design, and methods. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99(supplement 8):S12–S18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00411-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH collaborative research Ggroup. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336(16):1117–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-sodium collaborative research group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(1):3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure-lowering diet: the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;74(1):80–89. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute. Your Guide to Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH, May 2009, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(7):713–720. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(6):531–540. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Consistency with the DASH diet and incidence of heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(9):851–857. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karanja N, Lancaster KJ, Vollmer WM, et al. Acceptability of sodium-reduced research diets, including the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, among adults with prehypertension and stage 1 hypertension. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(9):1530–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollmer WM, Sacks FM, Ard J, et al. Effects of diet and sodium intake on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the DASH-sodium trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;135(12):1019–1028. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-12-200112180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray GA, Vollmer WM, Sacks FM, et al. A further subgroup analysis of the effects of the DASH diet and three dietary sodium levels on blood pressure: results of the DASH-sodium trial. American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(2):222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chobanian AV, Hill M, Roccella EJ. National heart, lung, and blood institute workshop on sodium and blood pressure: a critical review of current scientific evidence. Hypertension. 2000;35(4):858–863. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. Washington, DC, USA: US Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funk KL, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, et al. PREMIER—a trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control: intervention design and rationale. Health Promotion Practice. 2008;9(3):271–280. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Lin PH, et al. Effects of individual components of multiple behavior changes: the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(5):545–560. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(7):485–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(16):2083–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Appel LJ, Loria C, et al. Reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with weight loss: the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(5):1299–1306. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang YF, Yancy WS, Jr., Yu D, et al. The relationship between dietary protein intake and blood pressure: results from the PREMIER study. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2008;22(11):745–754. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, et al. Reductions in dietary energy density are associated with weight loss in overweight and obese participants in the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(5):1212–1221. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(supplement 4):73–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell MK, Resnicow K, Carr C, et al. Process evaluation of an effective church-based diet intervention: body & Soul. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34(6):864–880. doi: 10.1177/1090198106292020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary) 2004;(99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rankins J, Sampson W, Brown B, Jenkins-Salley T. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) intervention reduces blood pressure among hypertensive African American patients in a neighborhood health care center. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2005;37(5):259–264. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, et al. A barber-based intervention for hypertension in African American men: design of a group randomized trial. American Heart Journal. 2009;157(1):30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones DE, Weaver MT, Friedmann E. Promoting heart health in women: a workplace intervention to improve knowledge and perceptions of susceptibility to heart disease. AAOHN Journal. 2007;55(7):271–276. doi: 10.1177/216507990705500703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kark J, Shemi G, Friedlander Y, et al. Does religious observance promote health? mortality in secular versus religious kibbutzim in Israel. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;86(3):341–346. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oman D, Reed D. Religion and mortality among the community-dwelling elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(10):1469–1475. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eng E, Hatch J, Callan A. Institutionalizing social support through the church and into the community. Health Education Quarterly. 1985;12(1):81–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lasater TM, Becker DM, Hill MN, Gans KM. Synthesis of findings and issues from religious-based cardiovascular disease prevention trials. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;(7, supplement):S46–S53. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thumma S. Mega-churches today 2000: summary of data from the faith communities today 2000 project. 2001, http://hirr.hartsem.edu/org/faith_megachurches_FACTsummary.html.

- 53.TOHP1.The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. The effects of non-pharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high-normal levels: results of the trials of hypertension prevention, phase I. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267(9):1213–1220. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480090061028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.TOHP2.The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure: the trials of hypertension prevention, phase II. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(6):657–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Demark-Wahnefried W, McClelland JW, Jackson B, et al. Partnering with African American churches to achieve better health: lessons learned during the black churches united for better health 5 a day project. Journal of Cancer Education. 2000;15(3):164–167. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karanja N, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, Kumanyaki SK. Stems to soulful living (steps): a weight loss program for African-American women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12(3):363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooper RS, Kennelly JF, Durazo-Arvizu R, Oh HJ, Kaplan G, Lynch J. Relationship between premature mortality and socioeconomic factors in black and white populations of US metropolitan areas. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):464–473. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research in Health. San Francisco, Calif, USA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dodani S, Fields JZ. Implementation of the fit body and soul, a church-based life style program for diabetes prevention in high-risk African Americans: a feasibility study. Diabetes Educator. 2010;36(3):465–472. doi: 10.1177/0145721710366756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dodani S, Kramer K, Williams L, et al. A church-based behavioral lifestyle program for diabetes prevention in African Americans: Translation into the religious community. Ethnicity & Diseases. 2009;19(2):135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dodani S, Champagne C, Pankey S. A Faith- based hypertension control and prevention program for African American churches. training of church leaders for effective program delivery. doi: 10.4061/2011/820101. International J of Hypertension. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7212):774–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simmons D, Voyle J, Swinburn B, O’Dea K. Community-based approaches for the primary prevention of non-insulin- dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 1997;14(7):519–526. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199707)14:7<519::AID-DIA414>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(supplement 1):68–81. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumanyika SK, Charleston JB. Lose weight and win: a church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among black women. Patient Education and Counseling. 1992;19(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(92)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerber JC, Stewart DL. Prevention and control of hypertension and diabetes in an underserved population through community outreach and disease management: a plan of action. Journal of the Association for Academic Minority Physicians. 1998;9(3):48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith ED, Merritt SL, Patel MK. Church-based education: an outreach program for African Americans with hypertension. Ethnicity & Health. 1997;2(3):243–253. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1997.9961832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oexmann MJ, Ascanio R, Egan BM. Efficacy of a church-based intervention on cardiovascular risk reduction. Ethnicity & Disease. 2001;11(4):817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oexmann MJ, Thomas JC, Taylor KB, et al. Short-term impact of a church-based approach to lifestyle change on cardiovascular risk in African Americans. Ethnicity & Disease. 2000;10(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiist WH, Flack JM. A church-based cholesterol education program. Public Health Reports. 1990;105(4):381–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flack JM, Wiist WH. Cardiovascular risk factor prevalence in African-American adult screenees for a church-based cholesterol education program: the northeast oklahoma city cholesterol education program. Ethnicity & Disease. 1991;1(1):78–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baskin ML, Resnicow K, Campbell MK. Conducting health interventions in black churches: a model for building effective partnerships. Ethnicity & Disease. 2001;11(4):823–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eng E, Hatch JW. Networking between agencies and black churches: the lay health advisor model. Journal of Prevention in Human Services. 1991;10(1):123–146. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Appel LJ. Lifestyle modification as a means to prevent and treat high blood pressure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2003;14(2, supplement 2):S99–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070141.69483.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rankins J, Wortham J, Brown LL. Modifying soul food for the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet (DASH) plan: implications for metabolic syndrome (DASH of Soul) Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17(3, supplement 4):S4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moore TJ, Alsabeeh N, Apovian CM, et al. Weight, blood pressure, and dietary benefits after 12 months of a web-based nutrition education program (DASH for health): longitudinal observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2008;10(4, article e52) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karanja NM, Obarzanek E, Lin PH, et al. Descriptive characteristics of the dietary patterns used in the dietary approaches to stop hypertension trial. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99(8, supplement):S19–S27. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fongwa MN, Evangelista LS, Doering LV. Adherence to treatment factors in hypertensive African American women. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21(3):201–207. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on the Detection,Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure(JNC V) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1993;153(2):154–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The sixth report of the Joint National Committeeon the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cutler JA, Follmann D, Scott Allender P. Randomized trials of sodium reduction: an overview. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;65(supplement 2):643S–651S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.643S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Law MR, Frost CD, Wald NJ. By how much does dietary salt reduction lower blood pressure? III—analysis of data from trials of salt reduction. British Medical Journal. 1991;302(6780):819–824. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6780.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beydoun MA, Wang Y. How do socio-economic status, perceived economic barriers and nutritional benefits affect quality of dietary intake among US adults? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;62(3):303–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bodor JN, Rose D, Farley TA, et al. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;11(4):413–420. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cassady D, Jetter KM, Culp J. Is price a barrier to eating more fruits and vegetables for low-income families? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(11):1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hosler AS, Rajulu DT, Fredrick BL, Ronsani AE. Assessing retail fruit and vegetable availability in urban and rural underserved communities. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;5(4, article A123) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jetter KM, Cassady DL. Increasing fresh fruit and vegetable availability in a low-income neighborhood convenience store: a pilot study. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11(5):694–702. doi: 10.1177/1524839908330808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bavikati VV, Sperling LS, Salmon RD, et al. Effect of comprehensive therapeutic lifestyle changes on prehypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 2008;102(12):1677–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ard JD, Carter-Edwards L, Svetkey LP. A new model for developing and executing culturally appropriate behavior modification clinical trials for African Americans. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(2):279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]