Abstract

The BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) inbred mouse strain displays a low sociability phenotype relevant to the first diagnostic symptom of autism, deficits in reciprocal social interactions. Previous studies have shown that BTBR mice exhibit reduced social approach, juvenile play, and interactive behaviors. The present study evaluated the behavior of the BTBR and C57BL/6J (B6) strains in social proximity. Subjects were closely confined and tested in four experimental conditions: same strain male pairs (Experiment 1); different strain male pairs (Experiment 2); same strain male pairs and female pairs (Experiment 3); and same strain male pairs treated with an anxiolytic (Experiment 4). Results showed that BTBR mice displayed decreased nose tip-to-nose tip, nose-to-head and upright behaviors and increased nose-to-anogenital, crawl under and crawl over behaviors. These results demonstrated avoidance of reciprocal frontal orientations in the BTBR, providing a parallel to gaze aversion, a fundamental predictor of autism. For comparative purposes, Experiment 3 assessed male and female mice in a three-chamber social approach test and in the social proximity test. Results from the three-chamber test showed that male B6 and female BTBR displayed a preference for the sex and strain matched conspecific stimulus, while female B6 and male BTBR did not. Although there was no significant interaction between sex and strain in the social proximity test, a significant main effect of sex indicated that female mice displayed higher levels of nose tip-to-nose tip contacts and lower levels of anogenital investigation (nose-to-anogenital) in comparison to male mice, all together suggesting different motivations for sociability in males and females. Systemic administration of the anxiolytic, diazepam, decreased the frequency of two behaviors associated with anxiety and defensiveness, upright and jump escape, as well as crawl under behavior. This result suggests that crawl under behavior, observed at high levels in BTBR mice, is elicited by the aversiveness of social proximity, and possibly serves to avoid reciprocal frontal orientations with other mice.

Keywords: autism, mouse models, BTBR, gaze aversion, social behavior, social proximity

1. Introduction

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder that is diagnosed by observable behaviors rather than specific biomarkers [2],[33]. The diagnostic symptoms of autism form a triad of behavioral deficits consisting of abnormal social interactions, impaired communication and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior [2]. A strong genetic component for the disorder [1],[5],[29] is evident in the high (70–90%) concordance rates for autism in monozygotic twins [24],[37],[64] and the markedly high heritability of the individual diagnostic symptoms [58],[59]. Neuropathologies such as increased gross brain volume [7],[17],[30],[51],[55] and reduction in size of the corpus callosum [13],[22],[25],[39],[52] are also frequently associated with the disorder.

Because the etiology of autism may involve complex and heterogenous genetic and experiential interactions, mouse models are critical to isolating its underlying mechanisms [1],[21],[32],[43],[44]. Current animal models of autism include both inbred mouse strains that exhibit relevant behavioral characteristics [45],[48] and mouse lines engineered with targeted mutations of candidate genes [43],[46]. Inbred mouse strains are particularly useful in relating existing phenotypes to potential genetic or physiological abnormalities. However, the complexity of mouse social behavior presents a challenge to designing tasks to assess social interactions relevant to autism. A combination of social interaction tests have been used to identify low social responsiveness in inbred candidate strains [4],[11],[12],[18],[19],[20],[41],[45],[46],[48],[54],[70]. Such tests quantify social tendencies in mice by measuring the duration of proximity with another animal and the frequency of behaviors which characterize the nature of interactions. Results from previous social interaction tests have indicated that the inbred BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mouse strain displays several social deficits congruent with the diagnostic criteria of autism including reduced social approach [41],[69], huddling, social investigation [11],[54] and juvenile play [41],[70]. In comparison to the C57BL/6J (B6) mouse strain, BTBR mice additionally displayed restricted interest in objects [50], repetitive grooming [50],[63], abnormal patterns of scent marking and unusual vocalizations [60],[62],[67], offering face validity to the core symptoms of autism.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent results for anxiety in BTBR mice. Baseline anxiety measured in the elevated plus maze (EPM) yielded conflicting results across studies: the duration of open arm time has been reported as reduced [53] and not different [8],[48],[68] from B6 mice; the number of open arm entries has been reported as increased [68], decreased [53] and not different [48] from those of B6 mice. Results from testing in the elevated zero maze indicated that BTBR mice consistently spent more time in the open arms [41],[53]. In addition, BTBR mice displayed heightened stress reactivity on the elevated plus maze following tail suspension [8]. Thus, the possible influence of anxiety on BTBR social behavior remains uncertain. The lack of preference for a social stimulus over a non-social stimulus [41],[48],[53],[69] and the low levels of social approach displayed by BTBR mice [11],[54] suggest social anxiety [38],[40] in this strain. Moreover, adminstration of an anxiolytic, diazepam, rescued BTBR preference for a social stimulus [53], suggesting that social approach is inhibited, at least in part, by anxiety.

The aim of the present study was to characterize BTBR behavior in a social proximity test and investigate the role of anxiety in that context. BTBR and B6 mice were tested in various pair configurations in a novel social proximity test that placed mice together in a small enclosure that required some physical contact of the animals. Specific avoidance behaviors, such as facial avoidance, are difficult to detect in contexts that permit substantial social distance, as mice are able to avoid contact with specific body parts by maintaining a comfortable distance from others. Assessment in social proximity conditions enables clearer analysis of specific components of avoidance behaviors. Potential investigatory, orientation, escape and avoidance behaviors are exposed by restricting social distancing of subjects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Subjects were 12–14 week old C57 BL/6J (B6) and BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mice (n=14/group/experiment, Experiments1–3; n=8 or 10/group, Experiment 4). All subjects were male except for Experiment 3, where both males and females were used. Naïve animals were used in each experiment, and except for Experiment 3 where males and females were initially run in the social approach test and later paired in the social proximity test, only a single test was run per animal. Animals were bred in-house from stock received from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were housed with same sex partners in groups of 4–5 in polycarbonate cages (26.5 × 17 × 11.5 h cm) fitted with microisolator tops. Ear tags were used for identification. Food and water were available ad libitum. Mouse colonies were contained within the animal facilities at the University of Hawaii in a room with controlled lighting (12:12 light/dark cycle with lights on at 0600), temperature (21 ± 3 °C), and humidity (52–58%).

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Use and Care Committee at the University of Hawaii and were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Apparatus

Social proximity testing was conducted in a clear rectangular chamber (7 × 14 × 30 cm H) constructed of acrylic plastic.

Social approach testing was conducted in a 3-chambered arena (41 × 70 cm × 28 cm H). The arena was constructed of black acrylic plastic except for a 6.35 cm high panel of clear acrylic plastic built into the front wall of all chambers. The center chamber was connected to the outer chambers by manually operated sliding doors. An inverted wire cup (Galaxy Cup, Kitchen Plus) was placed in each of the outer chambers.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Social Proximity Testing

Subjects were transported from the animal housing room to the experimental room at least 20 minutes before testing. For testing, two non-cagemate subjects were simultaneously placed in the testing chamber for a 10 minute trial. Conditions for each experiment were as follows:

-

Experiment 1

To examine within strain interactions, either 2 B6 males or 2 BTBR males were placed in the testing chamber.

-

Experiment 2

To examine between strain interactions, 1 B6 male and 1 BTBR male were placed together in the testing chamber.

-

Experiment 3

To examine sex and strain interactions, and the relationship between behaviors in the social approach test, and the social proximity test. Male and female B6 and BTBR subjects were first run in the social approach test, and, 7 days later, in the social proximity test. In the latter, pairs consisting of 2 B6 males, 2 B6 females, 2 BTBR males or 2 BTBR females were placed into the testing chamber.

-

Experiment 4

To examine the influence of anxiety on social behavior in the social proximity test, pairs of B6 males or pairs of BTBR males were injected with either vehicle or diazepam (DZP; 2 mg/kg, IP) 20 minutes before being placed in the testing chamber.

After each trial, subjects were removed from the apparatus and placed in a holding cage separate from naïve cagemates until all animals in the homecage were tested (30 minutes maximum), preventing transmission of the odor from the novel animal encountered in testing. Between trials, the apparatus was cleaned with 20% ethanol. Testing was conducted under dim red light during the light phase of the light/dark cycle. Video from two black and white CCTV cameras providing front and side views was transferred to a video merge processor which combined both channels into a single side-by-side output. The availability of both views aided in the discrimination of behaviors by reducing occlusion of one animal from view by the other. The output from the video processor displaying both the front and side view was transmitted to a DVD recorder for storage and subsequent analysis. The following behaviors were manually quantified:

Nose tip-to-nose tip (NN): Subject’s nose tip and/or vibrissae contact the nose tip and/or vibrissae of the other mouse.

Nose-to-head (NH): Subject’s nose or vibrissae contacts the dorsal, lateral, or ventral surface of other mouse’s head.

Nose-to-anogenital (NA): Subject’s nose or vibrissae contacts the base of the tail or anus of the other mouse.

Crawl Over (CO): Subject’s forelimbs cross the midline of the dorsal surface of the other mouse.

Crawl Under (CU): Subject’s head goes under the ventral surface of the other mouse to a depth of at least the ears of the subject animal crossing the midline of the other mouse’s body.

Upright (U): Subject displays a reared posture oriented towards the other mouse with head and/or vibrissae contact.

Jump Escape (JE): Subject makes a vertical leap with all feet leaving the ground.

2.3.2. Social Approach Testing

The three chamber/social approach test was conducted for subjects in Experiment 3 to provide comparative data for the social proximity test. Social approach testing was conducted 7 days prior to the social proximity test. The procedure for social approach testing was as previously described by Moy et al. [46],[47],[48]. Briefly, subjects were placed into the 3-chambered arena for a ten minute habituation period. At the end of the habituation period, subjects were placed into the center chamber while a sex, strain and age matched conspecific stimulus (not used in later testing) was placed in one of the stimulus cups. The social approach phase began when the doors were raised allowing free access to the entire arena for ten additional minutes. Time spent in each chamber was manually quantified for both the habituation and social approach phases of the test.

2.3.3 Statistical analysis

Data from the social proximity test of Experiments 1 and 2 and the social approach test of Experiment 3 were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data from the social proximity tests of Experiments 3 and 4 were analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with sex and strain as within group factors for experiment 3 and treatment and strain as within group factors for experiment 4. Post hoc comparisons were made using the Newman-Keuls test. Comparisons of social approach and social proximity scores used Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A probability level of p < 0.05 was adopted as the level of statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1- Social Proximity tests in BTBR and B6 male pairs

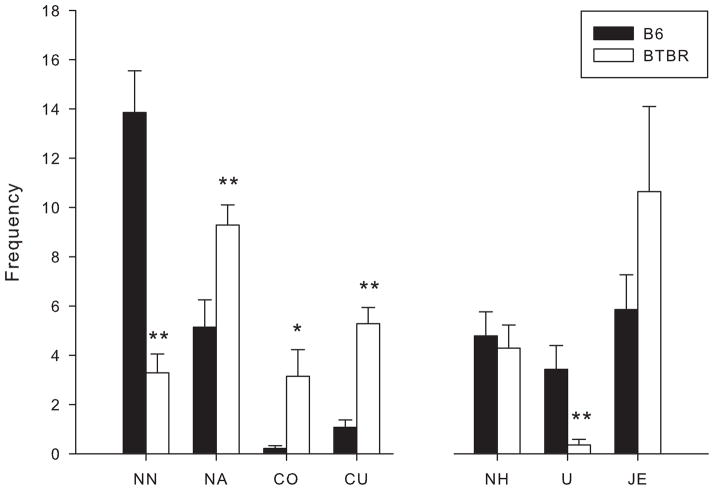

Confining subjects within the social proximity apparatus (Fig. 1) elicited markedly different behaviors in the BTBR and B6 strains (Fig. 2). BTBR males showed significantly less nose tip-to-nose tip contact [t(26) = 5.688, p < 0.0001] while displaying reliably higher nose-to-anogenital contact [t(26) = 3.011, p < 0.01] than B6 males. Upright behaviors, which often accompany contact with the mystacial vibrissae of the other animal, were displayed by only 3 of 14 BTBR mice, and were significantly decreased [t(26) = 3.100, p < 0.005] in comparison to B6 mice. BTBRs also showed significantly more crawl over [t(26) = 2.688, p < 0.05] and crawl under [t(26) = 5.871, p < 0.001] behaviors. Notably, in contrast to the crawl over and under behaviors of the BTBR strain, B6 mice oriented towards, and locomoted around, one another.

Figure 1.

BTBR mice confined in the social proximity test. The side walls of the clear colorless testing chamber are tinted a false gray to emphasize the area of confinement.

Figure 2.

Male B6 and BTBR mice were confined with a same strain partner in the social proximity test. Behavioral frequencies are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Behaviors measured were nose tip-to-nose tip contact (NN), nose-to-anogenital contact (NA), crawl over (CO), crawl under (CU), nose-to-head contact (NH), upright (U) and jump escape (JE). Significant differences are indicated by (*), p < 0.01 and (**), p < 0.001.

3.2. Experiment 2- Social Proximity tests in mixed male pairs: BTBR and B6 mice

When naïve BTBR and B6 mice were paired and confined in the social proximity test (Fig. 3), nose tip-to-nose tip contact failed to differentiate the two groups (t(26) = 0.171, p > 0.05). This appears to reflect that B6 mice initiated nose tip-to-nose tip contact with BTBR mice; however, such contact often elicited rapid head withdrawal by BTBR mice. Nose-to-head contact was decreased in BTBR mice [t(26) = 5.242, p < 0.001], while nose-to-anogenital contact [t(26) = 5.051, p < 0.001] and crawl under [t(26) = 4.417, p < 0.001] were increased. BTBR mice would often crawl under B6 mice and remain there, eliciting crawl over behavior from the B6, providing a likely explanation for the lack of difference between the strains for crawl over behavior. Table 1 presents individual scores for each subject in the 14 BTBR-B6 pairs, to illustrate the marked behavioral discrimination between the strains. BTBR mice consistently displayed higher frequencies of crawl under and anogenital contact than their B6 partner with only 1 tie for crawl under. BTBR mice displayed lower frequencies of head contact in all but 2 BTBR-B6 pairs, for which head contact scores were ties.

Figure 3.

Male B6 and BTBR mice were paired together in the social proximity test. Behavioral frequencies are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Behaviors measured were nose tip-to-nose tip contact (NN), nose-to-anogenital contact (NA), crawl over (CO), crawl under (CU), nose-to-head contact (NH), upright (U) and jump escape (JE). Significant differences are indicated by (*), p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Frequencies of 4 behaviors for each pair member of 14 B6/BTBR pairs, presenting which strain within each pair showed the higher number of behaviors.

| Pair | Nose-to-head | Nose-to-anogenital | Crawl Over | Crawl Under | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | BTBR | B6 | BTBR | B6 | BTBR | B6 | BTBR | |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 13 |

| 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 12 |

| 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| 11 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| 12 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 13 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 14 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Subjects with higher frequency of behavior within each pair | 12 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

3.3. Experiment 3- Social Approach and Social Proximity tests in male and female BTBR and B6 mice

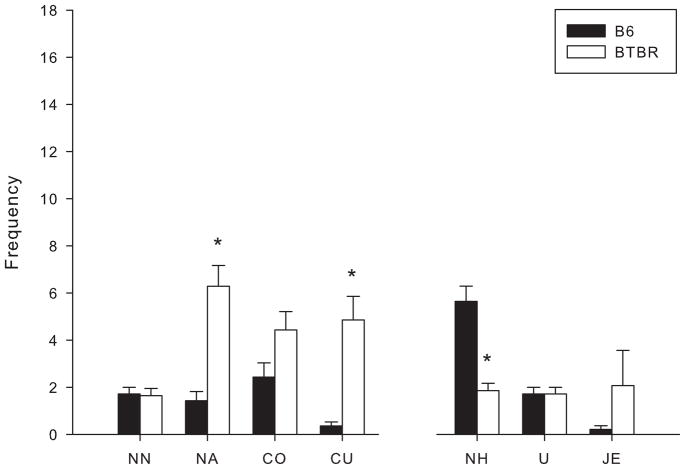

3.3.1. Social approach Test

B6 males spent significantly more time with the conspecific than with the empty cup [t(26) = 3.844, p < 0.001]; however, B6 females failed to show a significant preference for either stimulus [t(26) = 1.873, p > 0.05] (Fig. 4). BTBR mice showed an opposite pattern of gender effects: females spent more time with the conspecfic than with the empty cup [t(26) = 2.820, p < 0.01], while males showed no preference for either [t(26) = 0.227, p > 0.05].

Figure 4.

Male and female B6 and BTBR mice were assessed in the social approach test. Duration of time spent in each chamber is expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Significant differences in duration of time spent in the chamber containing the conspecific stimulus are indicated by (*), p < 0.01 and (**), p < 0.001.

3.3.2. Social Proximity Test

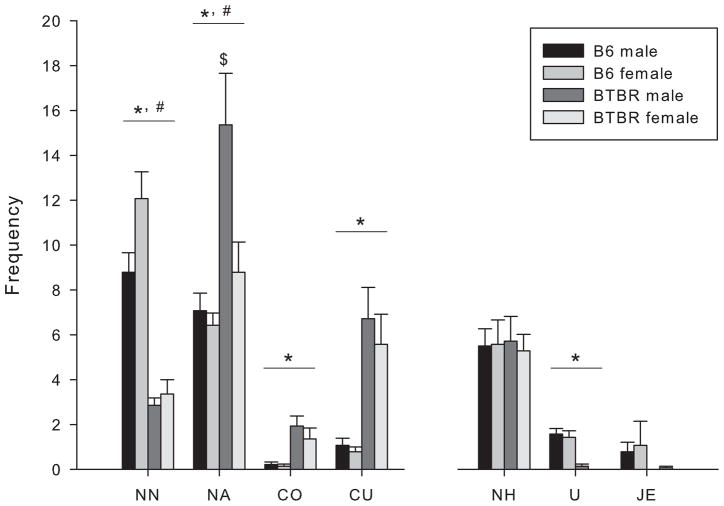

The behaviors showing a significant difference between BTBR and B6 mice in this experiment exactly matched those in Experiment 1 (Fig. 5). ANOVA showed a significant effect of strain for several behaviors. BTBR mice displayed reduced nose tip to-nose tip contact [F(1,52) = 79.280, p < 0.001] as well as upright posture [F(1,52) = 52.000, p < 0.001] when compared with B6 mice. Nose-to-head contact, which can be made from a side or rear approach, did not significantly differ between the strains [F(1,52) = 0.0014, p > 0.05]. BTBR mice displayed elevated nose-to-anogenital contact [F(1,52) = 14.179, p < 0.001]; crawl over [F(1,52) = 18.535, p < 0.001]; and crawl under [F(1,52) = 27.817, p < 0.001] behaviors, compared to B6 mice. The duration of time spent in the chamber containing the conspecific stimulus did not significantly correlate with any of the behaviors measured in the social proximity test.

Figure 5.

Male and Female B6 and BTBR mice were confined with a same sex and same strain partner in the social proximity test. Behavioral frequencies are expressed as mean (± S.E.M. Behaviors measured were nose tip-to-nose tip contact (NN), nose-to-anogenital contact (NA), crawl over (CO), crawl under (CU), nose-to-head contact (NH), upright (U) and jump escape (JE). (*) indicates a significant difference between BTBR and B6 mice, p < 0.001. (#) indicates a significant difference between males and females, p < 0.05. ($) indicates a significant difference from all other groups, p < 0.05.

ANOVA showed a significant main effect of sex in 2 of the 7 behaviors measured. Females showed more nose tip-to-nose tip nose contacts [F(1,52) = 50.161, p < 0.05], but fewer nose-to-anogenital contacts [F(1,52) = 6.515, p < 0.05] than males. Post hoc analysis on a significant interaction between sex and strain [F(1,52) = 4.400, p < 0.05] indicated that BTBR males performed more nose-to-anogenital contacts than any other group.

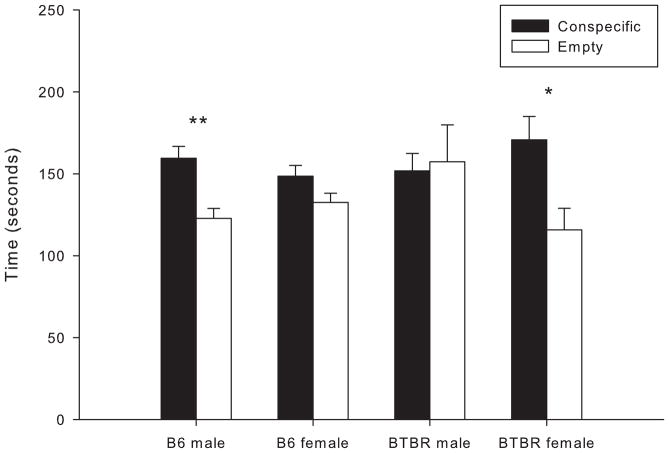

3.4. Experiment 4- Diazepam effects on Social Proximity Measures in male mice

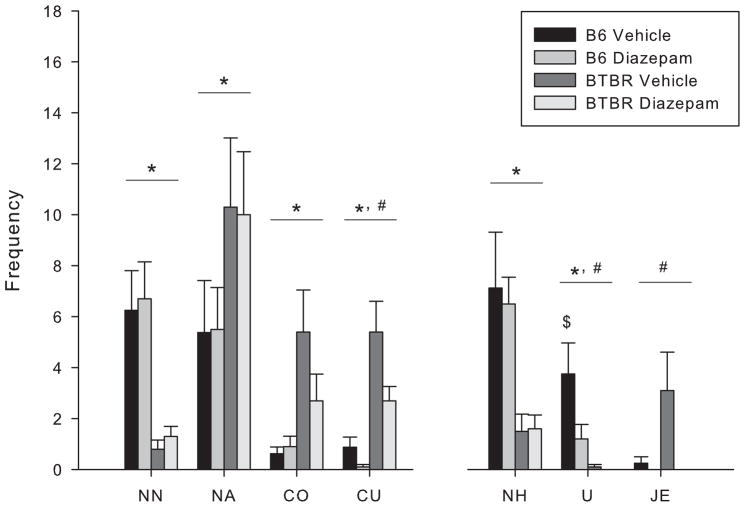

The pattern of strain differences evident in Experiments 1 and 3 was also seen in Experiment 4 (Fig 6). A significant main effect of strain showed that BTBR mice displayed elevated levels of nose-to-anogenital [F(1,34) = 4.199, p < 0.048], crawl over [F(1,34) = 9.573, p < 0.005] and crawl under [F(1,34) = 24.135, p < 0.001]; and fewer nose tip-to-nose tip contacts [F(1,34) = 26.808, p < 0.001], nose-to-head contacts [F(1,34) = 20.407, p < 0.001] and uprights [F(1,34) = 16.507, p < 0.001] than B6 mice, showing a pattern that is virtually identical to that of experiments 1 and 3.

Figure 6.

Male B6 and BTBR mice were administered vehicle or diazepam and confined with a same strain partner in social proximity test. Behavioral frequencies are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Behaviors measured were nose tip-to-nose tip contact (NN), nose-to-anogenital contact (NA), crawl over (CO), crawl under (CU), nose-to-head contact (NH), upright (U) and jump escape (JE). (*) indicates a significant difference between BTBR and B6 mice, p < 0.05. (#) indicates a significant difference between vehicle and diazepam treatment, p < 0.05. ($) indicates a significant difference from all other groups, p < 0.05.

A significant main effect of treatment showed that subjects administered diazepam displayed decreased crawl under [F(1,34) = 5.741, p < 0.05], upright [F(1,34) = 4.928, p < 0.05] and jump escape [F(1, 34) = 4.308, p < 0.05] behaviors. Following a significant interaction between strain and treatment [F(1,34) = 4.212, p < 0.05], post hoc analysis indicated that the B6 vehicle group made more uprights than any other group.

4. Discussion

The overarching goal of the present study was to determine how BTBR and B6 mice differ in response to enforced social proximity. Deficiencies in social behavior have been consistently reported for BTBR mice. In a three-chamber social approach test, BTBR mice failed to spend more time in the chamber containing a mouse within a cup compared to the chamber containing an empty cup [41],[48],[53],[63],[68],[69],[70]. BTBR mice also spent less time engaged in social interactions compared to B6 mice and other strains in neutral arena tests [11],[41]. In a semi-natural visible burrow system, BTBR mice showed decreased front approach, rear approach, allogrooming and huddling behaviors; and increased self-grooming and alone behaviors [54]. Reductions in BTBR juvenile play have also been reported [41],[68],[70]. Collectively, these findings make BTBR mice the most extensively documented mouse line in terms of autism-like deficiencies in social approach and social behavior. In contrast, the current study used a novel social proximity test, in which mice were constrained in a space so small that virtually any form of body displacing movement would bring the subject mouse into contact with another mouse. As subjects confined in social proximity could hardly avoid touching the other animal, the question was not whether BTBR would avoid contact, as is typically a core variable in situations that permit avoidance, but how they would contact the other mouse, and how the other mouse might react to this contact.

The BTBR-B6 differences in contact behaviors across this series of studies was extremely consistent: Experiments 1 and 3 and the controls of Experiment 4, utilizing within-strain male pairs, both reported significant BTBR reductions in nose tip-to-nose tip frequencies, and upright behaviors, with significant increases in crawl under, crawl over, and nose-to-anogenital contacts. Experiments 1 and 4 used test-naïve mice, whereas the mice of Experiment 3 had previously been run in the social approach test, providing a clear consistency of results indicating that previous (noncontact) experience with an unfamiliar male mouse has little effect on the microstructure of social contacts for BTBR vs. B6 mice.

The differences in test situation may be crucial to an understanding of the fit between the present results and previous studies of social behaviors in BTBR mice. In contrast to the present results, previous studies have reported decreased push/crawl over behaviors in 21-day old BTBR as compared to B6 mice [41],[70]. While the use of juvenile mice in those studies, as compared to the adults used here, might suggest a developmental difference in the direction of BTBR/B6 differences, it is notable that these tests were run in a much larger arena affording opportunity for avoidance, and that the young BTBR mice showed reductions in behaviors such as allogrooming and face sniffs that are not only similar to those obtained here, but that are also highly compatible with a view that the BTBR mice were simply avoiding contact with each other. Crawl over/under reductions for the juveniles are compatible with this interpretation.

It is interesting, however, to note that the present results indicate increases in crawl under, crawl over, and nose-to-anogenital contacts for BTBR males, with the first of these being particularly consistent, appearing in mixed-strain as well as same-strain pairs. One factor that these have in common is orientation away from the direct frontal contact that is often seen in B6 mice, but much less often in BTBR (e.g. “nose sniffing” higher in B6 than BTBR [41],[70]). In fact, present findings suggest that the orientation that BTBR are avoiding may be quite specific: facing and nose tip-to-nose tip contact was virtually absent in BTBR in either of the present studies (Experiments 1, 3, and 4) utilizing same-strain pairs of males. The findings of severely reduced nose tip-to-nose tip contact in BTBR-BTBR pairs, but not in BTBR-B6 pairs (compare Fig. 3 to Fig. 2, Fig. 5 or Fig. 6) appears to reflect initiation of nose tip-to-nose tip contact by B6 mice and withdrawal by BTBR mice in the mixed strain pairs. This view that BTBR are actively avoiding the nose tip-to-nose tip orientation is strengthened by our observations that BTBR often jerked away from an oncoming approach in this orientation from a B6 animal. In addition, the present decrements in frontal approaches are consonant with previous findings for juvenile [70] and adult [54] BTBR mice.

Eye gaze serves as a nonverbal cue used to regulate several aspects of social interaction [34],[61] and reduced direct eye contact (gaze aversion) is associated with autism [42],[56],[65] to the extent that it may serve as an important predictor for early detection of the disorder [6],[16]. The present clear and consistent BTBR avoidance of reciprocal frontal orientations with other mice may present a potential parallel to such gaze aversion. That this deficit specifically involves reciprocal frontal orientation is additionally supported by the consistent finding (Experiments 1, 3, and 4) that upright behaviors, which almost always involve frontal vibrissae-to-vibrissae contact [10] are also significantly reduced in BTBR same-strain pairs. The consistently higher frequencies of crawl under behavior seen in BTBR mice may also be related to this phenomenon, possibly representing additional BTBR attempts to evade front-facing encounters.

Previous reports suggest increased reactivity to stressors in BTBR mice [8],[53]. The consistent findings of Experiments 1 and 3 of avoidance of nose tip-to-nose tip contact, uprights, and enhanced crawl under behavior, for BTBRs suggest that these mice find such contact aversive or stressful. Experiment 4 therefore examined the role of anxiety in these social proximity measures. Administration of the anxiolytic, diazepam, reduced uprights, due almost exclusively to changes in the B6 mice, as BTBRs showed minimal upright frequencies under any condition; demonstrating the ability of the anxiolytic to reduce a defensive behavior often seen in the context of agonistic behavior between mice [35],[36]. It also reduced crawl under displays, seen at consistently higher levels in BTBR mice and consonant with an interpretation that crawl under behaviors reflect a stressful response to attempted frontal contact. Jump escapes, which tended, albeit nonsignificantly, to be more frequent in the BTBR mice also declined with diazepam administration. This effect of diazepam is in agreement with previous studies showing that high frequencies of jump escape reflect elevated contextual anxiety [9],[26]. More specifically, diazepam was previously reported to reduce both jump escape and upright behaviors in BALB/c and Swiss mice tested in a mouse defensive test battery (MDTB) [27],[28]. Although diazepam is capable of inducing mild sedation at higher doses [23], sedative effects appear unlikely in the present study given the similar levels of investigation and orientation behaviors observed in treated and untreated mice.

The present findings of avoidance of nose tip-to-nose tip contact in BTBR mice, in conjunction with enhanced crawl under, as well as a nonsignificant tendency to show jump escapes from the social proximity situation, all suggest that social stimuli may produce higher levels of anxiety in these animals. Previous studies of anxiety in BTBR mice have been somewhat inconsistent, in aggregate failing to indicate a strong difference between these, and B6 mice. While low levels of anxiety-like behaviors for BTBR have been reported in a variety of tests: Elevated plus-maze (EPM) [48]; light-dark test [68]; open field [41],[63],[70]; and elevated zero maze [41], Pobbe et al. [53] reported decreased open arm durations and increased risk assessment in BTBR mice, suggesting increased anxiety in the EPM. Neither Benno et al. [8], nor Yang et al. [68] found open arm differences in the EPM between BTBR and B6 mice that had not been stressed. However, Benno et al. reported a decrease in open arm duration following tail suspension stress, raising the possibility that BTBR mice are more reactive to stress, potentially impacting their scores on tests such as the EPM.

In the MDTB, BTBR mice displayed increased vocalizations when confronted with the anesthetized predator, suggesting increased defensiveness, but failed to show the immobility typically associated with the predator context [53]: in aggregate suggesting only a mild enhancement of anxiety to this animate, but nonconspecific, stressor. However, the Pobbe et al. [53] report demonstrating that diazepam can rescue deficits in social approach by BTBR mice in the three chamber social approach test, suggests that defensiveness to a social stimulus may be an important contributor to the avoidance by BTBR males of conspecifics.

Finally, the social approach test was run in order to provide a comparison to the social proximity test. BTBR showed reduced social approach in the three chamber test, and avoidance of specific aspects of contact with a conspecific in the social proximity test. However, no significant correlations were obtained between variables of the two tests, even though the male BTBR-B6 differences were in agreement. Sex differences in the three-chamber test were striking: B6 males and BTBR females displayed a social approach preference; however, B6 females and BTBR males did not. The BTBR data are interesting, considering the sexual dimorphic aspect of autism, in which the male:female ratio ranges from 2 to 4:1 [15],[57],[66],[71]. However, while these social approach data for males of both strains are consistent with previous findings [12],[41],[48] the female data differed from previous studies [63],[68] reporting no sex differences in the social approach behaviors of these strains. This may possibly reflect differences in the stimuli used: the current study used a same sex conspecific of the same strain as the social stimulus, whereas previous studies used a different stimulus strain (129Sv/ImJ). Individuals of inbred strains, such as B6 and BTBR, are not readily discriminable by scent [3],[14],[31],[49]. For example, a habituation/dishabituation task, which exposes the subject to the same stimulus animal over consecutive trials followed by a trial exposing a novel stimulus animal, showed that when B6 mice are used as stimuli, presentation of a novel B6 fails to elicit a change in scent marking by the subject [3]. Thus, a stimulus of the same strain for these (group-housed) animals may have been perceived as a familiar cage-mate, resulting in a behavioral response different from that to a perceptibly unfamiliar mouse.

In summary, the current study provided a microanalysis of social behaviors in a situation in which mice are constrained to close contact with each other. BTBR mice showed a consistent pattern of avoidance of nose-to-nose contact, and also reductions in upright behaviors in which mice face each other with contact between their mystacial vibrissae. They also showed high levels of crawl under behaviors that may have functioned to reduce contact with the nose/face of the other mouse. The crawl under and upright behaviors were reduced by the anxiolytic diazepam, consistent with a view that these behaviors reflect stress or anxiety to facial contact. Diazepam also reduced jump escapes, which tended to be higher, albeit not significantly so, in BTBR males. These findings may provide a specific parallel to the gaze aversion responses that are commonly reported in autistic individuals, contributing to a view that these mice constitute excellent models for the analysis of autistic-like behaviors. The current results also suggest that the social proximity paradigm, which is simple, easy to score, and highly effective at discriminating BTBR and B6 mice, is a useful tool for assessment of particular social behaviors in mice.

Research Highlights.

BTBR mice display gaze aversion-like behavior

A novel social proximity test shows clear behavioral discrimination between BTBR T+ tf/J and C57BL/6J mice

Diazepam alters mouse social behavior in social proximity

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant MH081845-01A2 to RJB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Andres C. Molecular genetics and animal models in autistic disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arakawa H, Arakawa K, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. A new test paradigm for social recognition evidenced by urinary scent marking behavior in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;190:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arakawa H, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Colony formation of C57BL/6J mice in visible burrow system: identification of eusocial behaviors in a background strain for genetic animal models of autism. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25:63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, Swettenham J, Nightingale N, Morgan K, Drew A, et al. Psychological markers in the detection of autism in infancy in a large population. Brit J Psychiat. 1996;168:158–163. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauman ML, Kemper TL. Neuroanatomic observations of the brain in autism: a review and future directions. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benno R, Smirnova Y, Vera S, Ligget A, Schanz N. Exaggerated responses to stress in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse: an unusual behavioral phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard DC, Griebel G, Blanchard RJ. The Mouse Defense Test Battery: pharmacological and behavioral assays for anxiety and panic. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:97–116. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard RJ, Takahashi LK, Fukunaga KK, Blanchard DC. Functions of the vibrissae in the defensive and aggressive behavior of the rat. Aggressive Behav. 1977;3:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolivar VJ, Walters SR, Phoenix JL. Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodkin ES, Hagemann A, Nemetski SM, Silver LM. Social approach-avoidance behavior of inbred mouse strains towards DBA/2 mice. Brain Res. 2004;1002:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casanova MF, El-Baz A, Mott M, Mannheim G, Hassan H, Fahmi R, et al. Reduced gyral window and corpus callosum size in autism: possible macroscopic correlates of a minicolumnopathy. J Autism Dev Disord Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:751–764. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0681-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheetham SA, Thom MD, Jury F, Ollier WER, Beynon RJ, Hurst JL. The genetic basis of individual-recognition signals in the mouse. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cialdella P, Mamelle N. An epidemiological study of infantile autism in a French department (Rhône): a research note. J Child Psychol Psyc. 1989;30:165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clifford S, Young R, Williamson P. Assessing the Early Characteristics of Autistic Disorder using Video Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of Brain Overgrowth in the First Year of Life in Autism. JAMA. 2003;290:337–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawley JN. Designing mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autistic-like behaviors. Ment Retard Dev D R. 2004;10:248–258. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral assays relevant to the symptoms of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:448–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawley JN. Behavioral phenotyping strategies for mutant mice. Neuron. 2008;57:809–818. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiCicco-Bloom E, Lord C, Zwaigenbaum L, Courchesne E, Dager SR, Schmitz C, et al. The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6897–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egaas B, Courchesne E, Saitoh O. Reduced size of corpus callosum in autism. Arch Neurol-Chicago. 1995;52:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ennaceur A, Michalikova S, van Rensburg R, Chazot P. Are benzodiazepines really anxiolytic?: Evidence from a 3D maze spatial navigation task. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:136–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B. Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:943–955. doi: 10.1038/35103559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frazier TW, Hardan AY. A meta-analysis of the corpus callosum in autism. Biol Psychiat. 2009;66:935–941. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griebel G, Blanchard DC, Jung A, Lee JC, Masuda CK, Blanchard RJ. Further evidence that the mouse defense test battery is useful for screening anxiolytic and panicolytic drugs: effects of acute and chronic treatment with alprazolam. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1625–1633. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griebel G, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Characterization of the behavioral profile of the non-peptide CRF receptor antagonist CP-154,526 in anxiety models in rodents: comparison with diazepam and buspirone. Psychopharmacology. 1998;138:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s002130050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griebel G, Stemmelin J, Scatton B. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant in models of emotional reactivity in rodents. Biol Psychiat. 2005;57:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta AR, State MW. Recent Advances in the Genetics of Autism. Biol Psychiat. 2007;61:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardan AY, Minshew NJ, Mallikarjuhn M, Keshavan MS. Brain Volume in Autism. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:421–424. doi: 10.1177/088307380101600607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst JL, Payne CE, Nevison CM, Marie AD, Humphries RE, Robertson DH, et al. Individual recognition in mice mediated by major urinary proteins. Nature. 2001;414:631–634. doi: 10.1038/414631a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Insel TR. Mouse models for autism: report from a meeting. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:755–757. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1968;35:100–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleinke CL. Gaze and eye contact: a research review. Psychol Bull. 1986;100:78–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kršiak M. Effects of drugs on behaviour of aggressive mice. Brit J Pharmacology. 1979;65:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1979.tb07861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudryavtseva NN, Bondar NP. Anxiolytic and Anxiogenic Effects of Diazepam in Male Mice with Different Experience of Aggression. B Exp Biol Med+ 2002;133:372–376. doi: 10.1023/a:1016202205966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lichtenstein P, Carlström E, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Anckarsäter H. The Genetics of Autism Spectrum Disorders and Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Childhood. Am J Psychiat. 2010 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Fyer AJ, Klein DF. Social Phobia: Review of a Neglected Anxiety Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1985;42:729–736. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300097013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manes F, Piven J, Vrancic D, Nanclares V, Plebst C, Starkstein SE. An MRI Study of the Corpus Callosum and Cerebellum in Mentally Retarded Autistic Individuals. J Neuropsych Clin N. 1999;11:470–474. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcin MS, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiology of social anxiety disorder: the relevance of fear and anxiety. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2003;417:51–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFarlane HG, Kusek GK, Yang M, Phoenix JL, Bolivar VJ, Crawley JN. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+ tf/J mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:152–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mirenda PL, Donnellan AM, Yoder DE. Gaze behavior: A new look at an old problem. J Autism Dev Disord. 1983;13:397–409. doi: 10.1007/BF01531588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moy SS, Nadler JJ. Advances in behavioral genetics: mouse models of autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:4–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Magnuson TR, Crawley JN. Mouse models of autism spectrum disorders: the challenge for behavioral genetics. Am J Med Genet. 2006;142C:40–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, Barbaro RP, Johns JM, Magnuson TR, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Nonneman RJ, Grossman AW, Murphy DL, et al. Social approach in genetically engineered mouse lines relevant to autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Nonneman RJ, Segall SK, Andrade GM, et al. Social approach and repetitive behavior in eleven inbred mouse strains. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pearson BL, Defensor EB, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. C57BL/6J mice fail to exhibit preference for social novelty in the three-chamber apparatus. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearson BL, Pobbe RLH, Defensor EB, Oasay L, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, et al. Motor and cognitive stereotypies in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piven J, Arndt S, Bailey J, Havercamp S, Andreasen N, Palmer P. An MRI study of brain size in autism. Am J Psychiat. 1995;152:1145–1149. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piven J, Bailey J, Ranson B, Arndt S. An MRI study of the corpus callosum in autism. Am J Psychiat. 1997;154:1051–1056. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pobbe RLH, Defensor EB, Pearson BL, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. General and social anxiety in the BTBR T+ tf/J mouse strain. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pobbe RLH, Pearson BL, Defensor EB, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Expression of social behaviors of C57BL/6J versus BTBR inbred mouse strains in the visible burrow system. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Redcay E, Courchesne E. When Is the Brain Enlarged in Autism? A Meta-Analysis of All Brain Size Reports. Biol Psychiat. 2005;58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richer JM, Coss RG. Gaze aversion in autistic and normal children. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1976;53:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1976.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritvo E, Freeman B, Pingree C, Mason-Brothers A, Jorde L, Jenson W. The UCLA-University of Utah epidemiologic survey of autism: prevalence. Am J Psychiat. 1989;146:194–199. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ronald A, Happé F, Bolton P, Butcher LM, Price TS, Wheelwright S, et al. Genetic heterogeneity between the three components of the autism spectrum: a twin study. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2006;45:691–699. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215325.13058.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ronald A, Happé F, Price TS, Baron-Cohen S, Plomin R. Phenotypic and genetic overlap between autistic traits at the extremes of the general population. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2006;45:1206–1214. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000230165.54117.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roullet FI, Wohr M, Crawley JN. Female urine-induced male mice ultrasonic vocalizations, but not scent-marking, is modulated by social experience. Behav Brain Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruffman T, Garnham W, Rideout P. Social Understanding in Autism: Eye Gaze as a Measure of Core Insights. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2001;42:1083–1094. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scattoni ML, Gandhy SU, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silverman JL, Tolu SS, Barkan CL, Crawley JN. Repetitive self-grooming behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism is blocked by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:976–989. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steffenburg S, Gillberg C, Hellgren L, Andersson L, Gillberg IC, Jakobsson G, et al. A Twin Study of Autism in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. J Child Psychol Psyc. 1989;30:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Volkmar FR, Mayes LC. Gaze Behavior in Autism. Dev Psychopathol. 1990;2:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Volkmar FR, Szatmari P, Sparrow SS. Sex differences in pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1993;23:579–591. doi: 10.1007/BF01046103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wohr M, Roullet FI, Crawley JN. Reduced scent marking and ultrasonic vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00582.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang M, Clarke AM, Crawley JN. Postnatal lesion evidence against a primary role for the corpus callosum in mouse sociability. Eur J Neurosci. 2009:1663–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang M, Scattoni ML, Zhodzishsky V, Chen T, Caldwell H, Young WS, et al. Social approach behaviors are similar on conventional versus reverse lighting cycles, and in replications across cohorts, in BTBR T+tf/J, C57BL/6J, and vasopressin receptor 1B mutant mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2007;1:1–9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08/001.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang M, Zhodzishsky V, Crawley JN. Social deficits in BTBR T+ tf/J mice are unchanged by cross-fostering with C57BL/6J mothers. Int J Devl Neuroscience. 2007;25:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yeargin-Allsopp M, Rice C, Karapurkar T, Doernberg N, Boyle C, Murphy C. Prevalence of Autism in a US Metropolitan Area. JAMA. 2003;289:49–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]