Summary

-

1

Intrarenal oxygen availability is the balance between supply, mainly dependent on renal blood flow, and demand, determined by the basal metabolic demand and the energy-requiring tubular electrolyte transport. Renal blood flow is maintained within close limits in order to sustain stable glomerular filtration, so increased intrarenal oxygen consumption is likely to cause tissue hypoxia.

-

2

The increased oxygen consumption is closely linked to increased oxidative stress, which increases mitochondrial oxygen usage and reduces tubular electrolyte transport efficiency; both contributing to increased total oxygen consumption.

-

3

Tubulointerstitial hypoxia stimulates productions of collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin, indications of increased fibrogenesis. Furthermore, the hypoxic environment induces epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation and aggravating fibrosis, which result in reduced peritubular blood perfusion and oxygen delivery due to capillary rarefaction.

-

3

Increased oxygen consumption, capillary rarefaction and increased diffusion distance due to the increased fibrosis per se further aggravate the interstitial hypoxia.

-

4

Recently, it has also been demonstrated that hypoxia simulates infiltration and maturation of immune cells, which provides an explanation for the general inflammation commonly associated with the progression of chronic kidney disease.

-

5

Therapies targeting interstitial hypoxia could potentially reduce the progression of chronic renal failure in millions of patients that otherwise are likely to eventually present with fully developed end-stage renal disease.

Keywords: Tubulointerstitial hypoxia, Oxidative stress, Oxygen consumption, Fibrosis

Introduction

In any given tissue, oxygen tension (pO2) is determined by the balance between oxygen (O2) delivery and consumption (QO2). O2 delivery is determined by blood flow and by O2 extraction from blood, whereas QO2 is affected by mitochondrial activity, cellular QO2 and electrolyte transport.

In the kidney, renal blood flow (RBF) constitutes approximately 25% of cardiac output during resting conditions. Since renal QO2 only equals a minute part of total body QO2, O2 extraction from the blood is generally low and arterio-venous O2 difference lower than in most other organs, meaning renal venous blood remains relatively well oxygenated even compared to arterial blood (1). However, in pioneering studies, Levy and colleagues demonstrated renal O2 shunting in pre-glomerular vessels from arterial to venous blood in canine kidneys, using labelled erythrocytes and O2 supersaturated perfusion fluid (2, 3). This phenomenon provides an explanation to why intrarenal pO2 values are remarkably lower than arterial pO2.

A heterogeneous environment

Despite precapillary shunting of O2 in the kidney, one might believe that the remarkably well-perfused kidney cortex should be protected from ischaemic insults. Still, ischaemic renal failure is a complication far more common than the corresponding injuries to heart, liver or brain. One explanation for this apparent paradox is the heterogeneous distribution of O2 within the kidney. Whereas the kidney cortex is highly perfused, the medulla only receives about 10% of the flow to the cortex. In combination with differences in local intrarenal O2 demand, these flow discrepancies result in an intrarenal O2 gradient with a cortical pO2 of about 40-45 mmHg, but an inner medullary pO2 as low as 10-15 mmHg (4, 5). However, it should be noticed that the cortico-medullary O2 gradient is contingent upon prevailing physiological conditions, as evident from the report by Stillman et al. showing that chronic salt depletion for four weeks caused marked cortical hypoxia whereas the medullary oxygenation increased to levels only found in the normally well-oxygenated kidney cortex (6).

The terminal electron carrier of the mitochondrial chain, cytochrome C oxidase, is oxidized at normal pO2 and is normally only reduced when O2 delivery is insufficient (7, 8). In the kidney however, cytochrome C oxidase is partially reduced already during normal physiology (9, 10). Reducing proximal tubular QO2 does not alter the redox state, but treatment with loop diuretics, e.g. bumetanide and furosemide, will increase oxidation of cytochrome C oxidase (10). In conclusion, medullary O2 delivery barely matches physiological demand and results in relative hypoxia as part of normal renal physiology (11), possibly explaining why a decreased medullary concentrating ability is the most common defect in acute renal failure and generally considered a good indication of impending renal failure (12).

There are several intrarenal mechanisms maintain normal pO2 within the kidney. These include altered O2 delivery, via either altered RBF or O2 extraction from the blood, but also changes in kidney QO2 due to altered O2 demand, secondarily to altered glomerular filtration rate (GFR), or altered efficiency for tubular sodium transport sodium transport (TNa) (13). However, QO2 is a main determinant of the intrarenal pO2 if RBF is unaltered and within normal range. Approximately 20% of the total renal QO2 is related to basal cellular O2 demanding processes and 80% is related to TNa, resulting in TNa being a major factor influencing total kidney QO2 (14).

Characteristics of chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common co-morbidity of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and hypertensive and diabetic kidney damage are well known causes of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (15). It is becoming widely accepted that, regardless of the initial cause of renal failure, tubulointerstitial fibrosis is the major cause of disease progression (16, 17). Typically, functional impairment in CKD correlates with particularly tubulointerstitial fibrosis, but also glomerulosclerosis. However, tubulointerstitial damage is closely correlated with reduced creatinine clearance and is currently the best predictor of disease progression (17, 18). Characteristic of tubulointerstitial damage is accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), infiltration of inflammatory cells, increased number of interstitial fibroblasts, α-smooth muscle actin expressing myofibroblasts, tubular atrophy and finally loss of peritubular capillaries (19).

Renal Hypoxia in Fibrotic Kidney Disease

Recently, hypoxia and altered O2 handling have received increased attention for their putative roles in the development of renal injury. Today, renal hypoxia, increased renal QO2 and oxidative stress are all thought to play important roles in progression of kidney disease. In 1989, Brazy et al. reported that proximal tubules isolated from early hypertensive SHR utilize more O2 than tubules from normotensive rats and respond with greater increase in QO2 to stimulation by noradrenaline (20). Similarly, QO2 by proximal tubular cells isolated from streptozotocin-diabetic rats was found by Körner et al. in 1994 to be greater than that of control animals (21). In several models of experimental kidney damage, tissue pO2 is significantly reduced throughout the kidney. O2 microelectrodes, blood oxygen level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging and pimonidazole staining have been used to demonstrate renal hypoxia in glomerulonephritic or uninephrectomized animals as well as in models of diabetic nephropathy, cyclosporine nephropathy and polycystic kidney disease (22-30). Finally, the aging kidney displays relative hypoxia despite only mild tubulointerstitial disease, which may indicate that hypoxia is an early occurrence in renal disease and that fibrosis correlates with the degree of tubulointerstitial injury (31). This suggests a causal role for hypoxia in fibrotic renal disease.

Hypertensive as well as diabetes-induced renal hypoxia is related to decreased electrolyte transport efficiency, defined as QO2 required for TNa (TNa/QO2). In 2001, Welch et al. used O2 electrodes to demonstrate reduced pO2 in the tissue, glomeruli and cortical tubules in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) compared to its normotensive counterpart. SHR also displayed reduced RBF, renal O2 delivery and GFR, resulting in lower TNa. However, since total renal QO2 was not decreased in SHR, it was concluded these animals display limited renal pO2, due to reduced TNa/QO2 (23). Similar reduction in TNa/QO2 has been reported in 2-kidney, 1-clip Goldblatt hypertension (2K,1C) rats (32). Oxidative stress is elevated in both the hypertensive and diabetic kidney and can affect all of the factors determining the intrarenal regional pO2 by reducing RBF, elevating mitochondrial respiration, and by altering the efficiency of tubular electrolyte transport processes (33). The hypoxic environment accelerates the fibrosis, which results in loss of peritubular capillaries, correlating with deterioration in renal function (Figure 1) (18). Furthermore, it was recently demonstrated that indoxyl sulfate, an uremic toxin that accumulates due to declining urinary clearance in CKD, induces massive oxidative stress resulting in accelerated kidney tissue hypoxia due to significantly elevated QO2 (34). Indeed, normalizing the oxidative stress will normalize renal QO2, pO2 and TNa/QO2 (23, 32, 35).

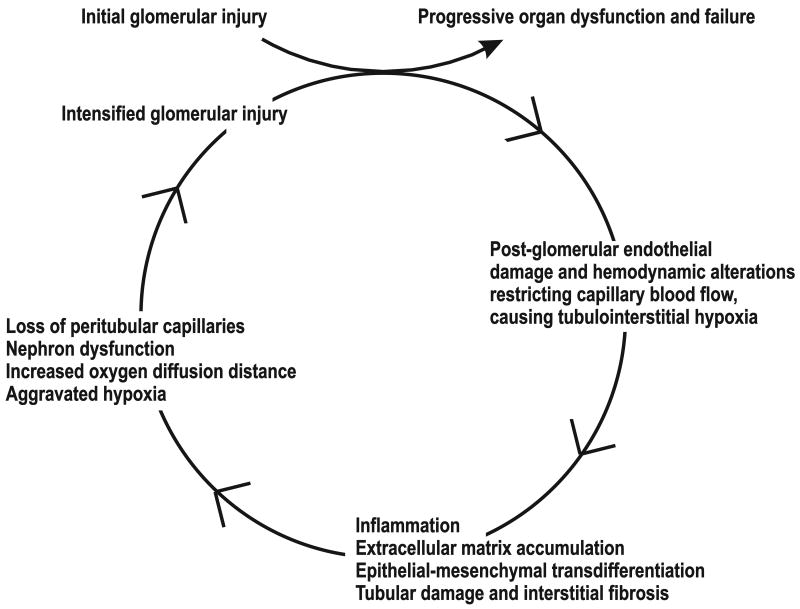

Figure 1.

The initial events linking increased oxidative stress to the development of chronic kidney disease. Elevated oxidative stress increases kidney oxygen consumption, whereas no compensatory increase in renal blood flow occurs. The developing hypoxia is not counteracted by activation of the hypoxia-inducible factors due to decreased sensitivity induced by the elevated oxidative stress. Chronic hypoxia induces histological alterations in the tubulointerstitium, which further aggravates the hypoxia and the development of chronic kidney disease.

The Chronic Hypoxia Hypothesis

In 1998, Fine and colleagues suggested chronic hypoxia as the common mediator of development of progressive renal disease, with hypoxia as the transmitter of glomerular injury to the tubulointerstitium (36). The stipulated “chronic hypoxia hypothesis” suggested that a primary glomerular disease will restrict post-glomerular flow and injure the downstream, peritubular capillaries. In turn, microvascular dysfunction will cause a hypoxic milieu and trigger a fibrotic response and the development of fibrosis in tubulointerstitial cells. By affecting close by capillaries and nephrons, the fibrotic response exacerbates hypoxia and fibrosis, leading to a vicious cycle that ultimately results in organ failure (Figure 2). This hypothesis provides an explanation for the progressive nature of fibrosis and has lately been corroborated in vitro as well as in vivo by studies showing a correlation between peritubular capillary loss and glomerular and tubulointerstitial scarring (37). Taken together, the decline in renal pO2 precedes matrix accumulation, suggesting hypoxia to be a pivotal stimulus for fibrogenesis that initiates and promotes fibrotic progression.

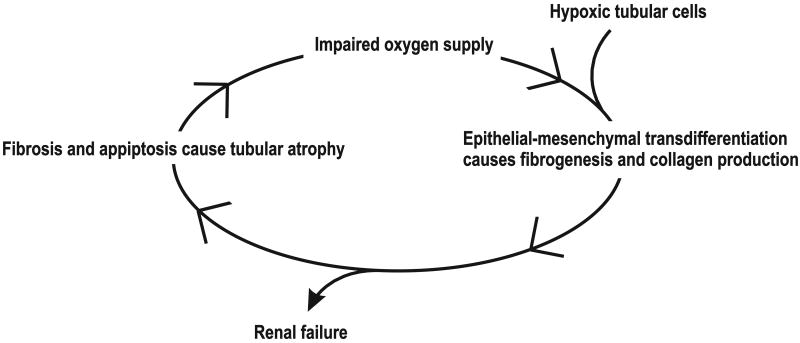

Figure 2.

The “Chronic hypoxia hypothesis” stipulates that hypoxia stimulates fibrogenesis and is the transmitter of an initial and progressive glomerular injury to the interstitium. By restricting post-glomerular flow, a primary glomerular disease causes hypoxia and triggers a fibrotic response by tubulointerstitial cells. When close-by capillaries are affected, hypoxia and fibrosis are exacerbated, eventually resulting in organ dysfunction and renal failure. Modified from (72).

Consequences of renal hypoxia

In normal physiology, an adequate hypoxic gene response will promote cell survival and adaptation, counteracting the reduction in pO2. Adequate gene response is elementary to maintain sufficient tissue pO2, which is mainly accomplished by the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) -1 and -2 that are both activated by hypoxia (38, 39). In the kidney, HIF isoforms HIF-1α and HIF-2α are expressed in tubules and interstitial cells, and in peritubular endothelial cells, mesangial cells and fibroblasts, respectively. It is likely that HIF-1α and HIF-2α exert unique as well as overlapping effects (40).

HIF is activated in conjunction with renal injury as a mechanism to prevent damage. The HIF α-subunit is degraded by an O2-dependent mechanism, resulting in accumulation of the α-subunit during hypoxia. The resulting heterodimerization with the constitutively expressed HIF β-subunit binds to hypoxia-response elements in the regulatory regions of numerous target genes, including erythropoietin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), heme-oxygenase (HO)-1, nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-regulated enzyme, which is required in order to normalize tissue pO2 (27, 41-43). Ohtomo et al. reported that HIF-1α induction by the hypoxia mimetic cobalt chloride in obese, hypertensive type 2 diabetic rats improved proteinuria and histological kidney injury (44). Trimetazidine is protective against ischaemia-reperfusion injury, and it was shown in a pig model of ischaemia-reperfusion damage that kidneys treated with trimetazidine had increased HIF-1α expression and developed less kidney damage (45). It has been reported by Faleo et al. that in Lewis rats, low concentrations of carbon monoxide are protective against renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury, and that these protective effects involve upregulated levels of HIF-1 and VEGF. All effects were completely reversed by the HIF-1α inhibitor YC-1 (46). In 2009, Bernhardt and colleagues demonstrated that HIF accumulation through donor pre-treatment with a single bolus of FG-4497, an inhibitor of the HIF α-subunit degrading enzyme prolyl hydroxylase, improved outcomes of transplanted rat kidney. The results also showed that FG-4497 reduced acute renal injury and early mortality, and improved long-term survival of the recipient animals (47).

Oxidative stress and renal hypoxia

In the event of a compromised hypoxic gene response, arterial hypertension, impaired salt handling, fibrosis and/or oxidative stress can result (48). Two weeks of chronic infusion of angiotensin II (Ang II) to rats using osmotic minipumps resulted in hypertension and elevated oxidative stress due to NADPH oxidase activation (25). Interestingly, these rats also presented with kidney tissue hypoxia. Activation of the renin-angiotensin system, as a compensatory mechanism to maintain normal systemic blood pressure, is also a possible explanation for the cortical hypoxia observed in chronically salt depleted rats (6). Although circulating Ang II levels are reduced in both patients and animal models of type 1 diabetes, intrarenal tissue levels of Ang II are elevated (49). In addition, oxidative stress will impair renal O2 sensing, as concluded from the lack of increased VEGF, HO-1 and erythropoietin in diabetic rat kidneys. This is further supported by the observation that several hypertensive animal models, including streptozotocin-diabetic rats, SHR, 2K,1C, Ang II-induced and Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats display normal or close to normal haematocrit (35, 50-52). Furthermore, Rosenberger et al. reported that treating hypoxic kidneys with the antioxidant 4-hydroxytempo paradoxically increased HIF-1α expression although tissue hypoxia, determined by pimonidazole staining, was reduced (30). The mechanism for oxidative stress-induced impaired HIF activation in the kidney remains to be determined. However, Welch and colleagues stipulated that from an evolutionary view, it might be beneficial to reduce O2 availability in situations of elevated oxidative stress, since this per se will be a “last line of defence” against uncontrolled superoxide products (53). The trade off of such a defence will be tissue hypoxia.

A Final Commmon Pathway between Renal Hypoxia and Fibrosis

As previously described, HIF induction serves to counteract short-term hypoxia. However, chronic hypoxia and increased HIF expression may be pro-fibrotic and HIF activation may itself induce fibrosis and glomerular injury (44, 54, 55). HIF induction has been reported to correlate with tubulointerstitial injury in biopsies from patients with diabetic nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, and chronic allograft nephropathy (29, 55-57). In early streptozotocin-induced diabetes, pigment epithelium-derived factor has been reported to be renoprotective. Its overexpression decreases albuminuria, inhibits renal matrix protein deposition and inhibits pathways and factors such as HIF-1α, NF-kappaB, Tumour necrosis factor α, and VEGF in experimental diabetes, as well as in primary human renal mesangial cells exposed to high glucose (58).

Recently, chronic tubulointerstitial hypoxia has been postulated as a final common pathway to ESRD. Tubular cells can be transformed into myofibroblasts, a process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation (EMT) (59). By exposing renal tubular cells to chronic hypoxia or the hypoxia mimetic cobalt chloride, Manotham et al. demonstrated that HIF activation can induce fibrosis (60). EMT was confirmed in vivo in a ligated kidney rat model of chronic kidney ischaemia. Compared to normal tubular cells, transformed cells have increased migratory capacity, and increased production of collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin (60). The tubular atrophy accompanying fibrosis is likely a result of EMT and apoptosis. It was therefore concluded that the initial events inducing renal failure occur mainly in the tubulointerstitium (26, 27). Furthermore, it was hypothesized that hypoxia-induced tubulointerstitial injury may induce interstitial fibrosis and rarefaction of peritubular capillaries, and that fibrosis in turn would impair the tubular and interstitial O2 supply. Together, these events would constitute a vicious cycle that aggravates and accelerates renal injury (Figure 3) (17, 26, 27, 61). In 2007, Higgins and colleagues reported that HIF-1α will increase in vitro EMT and cause epithelial cells to migrate in primary renal epithelial cells and renal proximal tubules from kidneys subjected to unilateral obstruction of the ureter (55). Although endothelial cell loss in fibrotic kidneys suggests the main renal endothelial response to hypoxia may be apoptosis, endothelial cells can also transdifferentiate and disrupt peritubular capillaries (62).

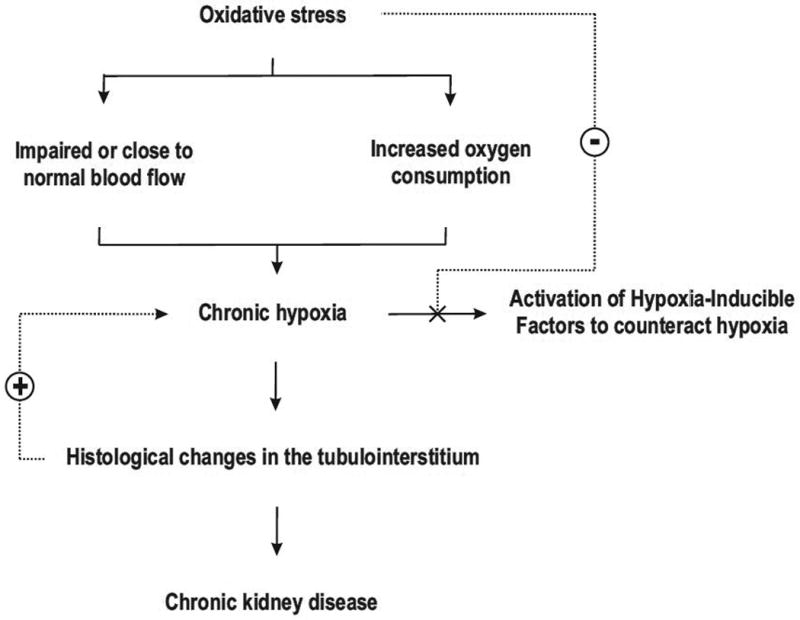

Figure 3.

Hypoxic tubular cells induce epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Transdifferentiated cells regulate renal fibrogenesis and stimulate production of collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin. Tubular atrophy occurs due to the combined effect of transdifferentiation and apoptosis. The impaired oxygen supply further accelerates the process and creates a vicious cycle.

Hypoxia-Induced Pathways

Numerous factors influence basal renal QO2 and may cause renal injury. Whereas oxidative stress results in renal hypoxia, hypoxia per se can activate post-translational collagen modifying enzymes that may lead to an extracellular matrix composition that is resistant to degradation (for review see Norman and Fine (28)). Hypoxia and fibrotic development will decrease anti-fibrotic factors such as hepatocyte growth factor and bone morphogenetic protein-7, parallel with increased expression of proinflammatory, vasoconstrictive, and fibrogenic factors, e.g. transforming growth factor (TGF) -β, connective tissue growth factor, platelet derived growth factor, angiopoietin-like 4, fibroblast growth factor-2, endothelin-1, and Ang II (19, 27, 28). Similarly, HIF-1α activation reduced renal injury in type 2 diabetic rats, a reduction parallel with reduced levels of connective tissue growth factor and TGF-β (44). Rundicki et al. reported that VEGF-A down-regulation in the presence of HIF activation predicted progression of proteinuria, renal function, and degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis in patients with proteinuric glomerulopathy (63).

Fibroblasts are the major ECM-producing cells in the tubulointerstitium (19). Hypoxia will induce ECM accumulation by increasing collagen production, up-regulating matrix proteins and suppressing matrix degradation in proximal tubular cells as well as in fibroblasts (28). HIF-1α inhibition in uninephrectomized Sprague-Dawley rats reduced natriuresis and medullary blood flow and also caused salt-sensitive hypertension (64).

Effects of Hypoxia on the Immune System

Inflammation is a well known component of a fibrotic response (19), and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the tubular interstitium correlates with deteriorating renal function (18). Higgins and colleagues found that in the absence of HIF-1α, tubulointerstitial fibrosis was inhibited along with reduced interstitial collagen deposition and infiltration of inflammatory cells in kidneys subjected to unilateral obstruction of the ureter (55). Hypoxia is part of normal immune cell development and function, and HIF-1α is a critical regulator of these processes. For instance, HIF-1α deficient mice develop abnormal B-lymphocytes and autoimmunity (65). In addition, chronic hypoxia causes accumulation of inflammatory cells at the site of injury, and can be a pro-inflammatory stimulus by activating immune cells (66). Hypoxia also causes production of pro-inflammatory factors and may alter the function of intrinsic stem cell populations in tubulointerstitial cells (67, 68). Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) provides fatty acids for production of lipid mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes (69), and are found in high concentrations in serum from patients with inflammatory diseases (70). It has been reported that HIF-2 α binds to the PLA2 promoter in mesangial cells and that, under inflammatory conditions, hypoxia can potentiate interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-1β-induced PLA2 expression and activity in renal mesangial cells (71).

In 2008, Rama and colleagues provided a link between hypoxia and immune activation when they showed that low O2 can induce HIF-1α-dependent dendritic cell differentiation and stimulate lymphocyte proliferation (66). Also in vivo, ischaemia-reperfusion injured mouse kidneys showed clear signs of dendritic cell maturation. After differentiation, the dendritic cells displayed elevated HIF-1α levels and downstream target genes such as VEGF and glucose transporter-1. Immunosuppression with rapamycin dose-dependently inhibited dendritic cell maturation, highlighting the pivotal role of the HIF-1α pathway for regulating the immune response.

Concluding Remarks

After first being suggested in 1998, the ‘chronic hypoxia hypothesis’ has gathered considerable support as a common mechanism for progression of CKD. It is now established that tubulointerstitial hypoxia results in renal fibrosis and deteriorated kidney function. Although renal tissue hypoxia can be at least semi-quantitatively estimated in patients using non invasive magnetic resonance imaging, considerable effort will be required before introducing it into clinical practice. Furthermore, CKD usually progresses during a prolonged period of time and a substantial commitment will be required from the pharmaceutical industry to establish functional therapeutical interventions effective in reducing hypoxia-induced kidney damage. However, the patient population affected by tubulointerstitial hypoxia is quite considerable and there are significant benefits from a functional treatment for these patients. Even slowing down the acute progression of CKD by a seemingly trivial rate could constitute a major benefit for those patients a decade later and postpone the progression to fully developed ESRD by several years.

Acknowledgments

The work from our laboratory presented in this review was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, the Lars Hierta Foundation, the Magnus Bergvall Foundation, the Åke Wiberg Foundation and NIH/NIDDK K99/R00 grant (DK077858).

List of Abbreviations

- 2K,1C

2-kidney, 1-clip Goldblatt hypertension

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HO

heme-oxygenase

- IL

interleukin

- O2

molecular oxygen

- PLA2

Phospholipase A2

- pO2

oxygen tension

- QO2

oxygen consumption

- RBF

renal blood flow

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TNa/QO2

QO2 required for TNa

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Deng A, Miracle CM, Suarez JM, et al. Oxygen consumption in the kidney: effects of nitric oxide synthase isoforms and angiotensin II. Kidney Int. 2005;68:723–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy MN, Sauceda G. Diffusion of oxygen from arterial to venous segments of renal capillaires. Am J Physiol. 1959;196:1336–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.6.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy MN, Imperial ES. Oxygen shunting in renal cortical and medullary capillaries. Am J Physiol. 1961;200:159–62. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.200.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aukland K, Krog J. Renal oxygen tension. Nature. 1960;188:671. doi: 10.1038/188671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brezis M, Heyman SN, Epstein FH. Determinants of intrarenal oxygenation. II. Hemodynamic effects. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:F1063–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.6.F1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stillman IE, Brezis M, Heyman SN, Epstein FH, Spokes K, Rosen S. Effects of salt depletion on the kidney: changes in medullary oxygenation and thick ascending limb size. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4:1538–45. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V481538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaban RS, Soltoff SP, Storey JM, Mandel LJ. Improved renal cortical tubule suspension: spectrophotometric study of O2 delivery. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:F50–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.238.1.F50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance B. Cellular oxygen requirements. Fed Proc. 1957;16:671–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balaban RS, Sylvia AL. Spectrophotometric monitoring of O2 delivery to the exposed rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:F257–62. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.241.3.F257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein FH, Balaban RS, Ross BD. Redox state of cytochrome aa3 in isolated perfused rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:F356–63. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.243.4.F356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonhardt KO, Landes RR. Oxygen tension of the urine and renal structures. Preliminary report of clinical findings. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:115–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196307182690301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brezis M, Rosen S, Silva P, Epstein FH. Renal ischemia: a new perspective. Kidney Int. 1984;26:375–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans RG, Eppel GA, Michaels S, et al. Multiple Mechanisms Act to Maintain Kidney Oxygenation during Renal Ischemia in Anesthetized Rabbits. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00647.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodwall EK, Laake H. The Relation between Oxygen Consumption and Transport of Sodium in the Human Kidney. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1964;16:281–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bleyer AJ, Chen R, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Appel RG. Clinical correlates of hypertensive end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:28–34. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9428448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Garcia Garcia G. The role of tubulointerstitial inflammation in the progression of chronic renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:c81–8. doi: 10.1159/000314656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risdon RA, Sloper JC, De Wardener HE. Relationship between renal function and histological changes found in renal-biopsy specimens from patients with persistent glomerular nephritis. Lancet. 1968;2:363–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohle A, Mackensen-Haen S, von Gise H, et al. The consequences of tubulo-interstitial changes for renal function in glomerulopathies. A morphometric and cytological analysis. Pathol Res Pract. 1990;186:135–44. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)81021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddy AA. Progression in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12:353–65. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazy PC, Klotman PE. Increased oxidative metabolism in renal tubules from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F818–25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.5.F818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korner A, Eklof AC, Celsi G, Aperia A. Increased renal metabolism in diabetes. Mechanism and functional implications. Diabetes. 1994;43:629–33. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palm F, Onozato M, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Blood pressure, blood flow, and oxygenation in the clipped kidney of chronic 2-kidney, 1-clip rats: effects of tempol and Angiotensin blockade. Hypertension. 2010;55:298–304. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch WJ, Baumgartl H, Lubbers D, Wilcox CS. Nephron pO2 and renal oxygen usage in the hypertensive rat kidney. Kidney Int. 2001;59:230–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palm F, Connors SG, Mendonca M, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors and nitric oxide sustain oxygenation in the clipped kidney of early Goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:345–51. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch WJ, Blau J, Xie H, Chabrashvili T, Wilcox CS. Angiotensin-induced defects in renal oxygenation: role of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H22–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00626.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nangaku M. Hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2004;98:e8–12. doi: 10.1159/000079927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nangaku M. Chronic hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:17–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman JT, Fine LG. Intrarenal oxygenation in chronic renal failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:989–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernhardt WM, Wiesener MS, Weidemann A, et al. Involvement of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors in polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:830–42. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberger C, Khamaisi M, Abassi Z, et al. Adaptation to hypoxia in the diabetic rat kidney. Kidney Int. 2008;73:34–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Kato H, Kojima I, et al. Hypoxia and expression of hypoxia-inducible factor in the aging kidney. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:795–805. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch WJ, Mendonca M, Aslam S, Wilcox CS. Roles of oxidative stress and AT1 receptors in renal hemodynamics and oxygenation in the postclipped 2K,1C kidney. Hypertension. 2003;41:692–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052945.84627.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao J, Nangaku M, Miyata T, et al. Imbalance of T-cell subsets in angiotensin II-infused hypertensive rats with kidney injury. Hypertension. 2003;42:31–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000075082.06183.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palm F, Nangaku M, Fasching A, et al. Uremia induces abnormal oxygen consumption in tubules and aggravates chronic hypoxia of the kidney via oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F380–6. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00175.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palm F, Cederberg J, Hansell P, Liss P, Carlsson PO. Reactive oxygen species cause diabetes-induced decrease in renal oxygen tension. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1153–60. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fine LG, Orphanides C, Norman JT. Progressive renal disease: the chronic hypoxia hypothesis. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;65:S74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang DH, Kanellis J, Hugo C, et al. Role of the microvascular endothelium in progressive renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:806–16. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–54. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonard MO, Cottell DC, Godson C, Brady HR, Taylor CT. The role of HIF-1 alpha in transcriptional regulation of the proximal tubular epithelial cell response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40296–304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nangaku M, Eckardt KU. Hypoxia and the HIF system in kidney disease. J Mol Med. 2007;85:1325–30. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen HH, Chen TW, Lin H. Pravastatin attenuates carboplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rodents via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-regulated heme oxygenase-1. Mol Pharmacol. 78:36–45. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park SK, Dadak AM, Haase VH, Fontana L, Giaccia AJ, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-induced gene expression occurs solely through the action of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha): role of cytoplasmic trapping of HIF-2alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4959–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4959-4971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummins EP, Taylor CT. Hypoxia-responsive transcription factors. Pflugers Arch. 2005;450:363–71. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohtomo S, Nangaku M, Izuhara Y, Takizawa S, Strihou CY, Miyata T. Cobalt ameliorates renal injury in an obese, hypertensive type 2 diabetes rat model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1166–72. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jayle C, Favreau F, Zhang K, et al. Comparison of protective effects of trimetazidine against experimental warm ischemia of different durations: early and long-term effects in a pig kidney model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1082–93. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00338.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faleo G, Neto JS, Kohmoto J, et al. Carbon monoxide ameliorates renal cold ischemia-reperfusion injury with an upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by activation of hypoxia-inducible factor. Transplantation. 2008;85:1833–40. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817c6f63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernhardt WM, Gottmann U, Doyon F, et al. Donor treatment with a PHD-inhibitor activating HIFs prevents graft injury and prolongs survival in an allogenic kidney transplant model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21276–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903978106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka T, Nangaku M. The role of hypoxia, increased oxygen consumption, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in progression of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 19:43–50. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283328eed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onozato ML, Tojo A, Leiper J, Fujita T, Palm F, Wilcox CS. Expression of NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase and protein arginine N-methyltransferase isoforms in diabetic rat kidney: effects of angiotensin II receptor blockers. Diabetes. 2008;57:172–80. doi: 10.2337/db06-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welch WJ, Baumgartl H, Lubbers D, Wilcox CS. Renal oxygenation defects in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: role of AT1 receptors. Kidney Int. 2003;63:202–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greene AS, Yu ZY, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr Role of blood volume expansion in Dahl rat model of hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H508–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawada N, Dennehy K, Solis G, et al. TP receptors regulate renal hemodynamics during angiotensin II slow pressor response. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F753–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00423.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y, Gill PS, Welch WJ. Oxygen availability limits renal NADPH-dependent superoxide production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F749–53. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00115.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidemann A, Bernhardt WM, Klanke B, et al. HIF activation protects from acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:486–94. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, et al. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Iwano M, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in the development of tissue fibrosis. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1128–32. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenberger C, Pratschke J, Rudolph B, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in human renal allograft biopsies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:343–51. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang JJ, Zhang SX, Mott R, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of pigment epithelium-derived factor in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1166–73. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00375.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ng YY, Huang TP, Yang WC, et al. Tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int. 1998;54:864–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manotham K, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, et al. Transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells induced by hypoxia. Kidney Int. 2004;65:871–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mackensen-Haen S, Bader R, Grund KE, Bohle A. Correlations between renal cortical interstitial fibrosis, atrophy of the proximal tubules and impairment of the glomerular filtration rate. Clin Nephrol. 1981;15:167–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krick S, Hanze J, Eul B, et al. Hypoxia-driven proliferation of human pulmonary artery fibroblasts: cross-talk between HIF-1alpha and an autocrine angiotensin system. Faseb J. 2005;19:857–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2890fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rudnicki M, Perco P, Enrich J, et al. Hypoxia response and VEGF-A expression in human proximal tubular epithelial cells in stable and progressive renal disease. Lab Invest. 2009;89:337–46. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li N, Chen L, Yi F, Xia M, Li PL. Salt-sensitive hypertension induced by decoy of transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in the renal medulla. Circ Res. 2008;102:1101–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kojima H, Gu H, Nomura S, et al. Abnormal B lymphocyte development and autoimmunity in hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha -deficient chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2170–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rama I, Bruene B, Torras J, et al. Hypoxia stimulus: An adaptive immune response during dendritic cell maturation. Kidney Int. 2008;73:816–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galindo M, Santiago B, Alcami J, Rivero M, Martin-Serrano J, Pablos JL. Hypoxia induces expression of the chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and IL-8 in human dermal fibroblasts. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:36–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Safronova O, Nakahama K, Onodera M, Muneta T, Morita I. Effect of hypoxia on monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) gene expression induced by Interleukin-1beta in human synovial fibroblasts. Inflamm Res. 2003;52:480–6. doi: 10.1007/s00011-003-1205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balsinde J, Winstead MV, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A(2) regulation of arachidonic acid mobilization. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:2–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nevalainen TJ, Haapamaki MM, Gronroos JM. Roles of secretory phospholipases A(2) in inflammatory diseases and trauma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petry C, Huwiler A, Eberhardt W, Kaszkin M, Pfeilschifter J. Hypoxia increases group IIA phospholipase A(2) expression under inflammatory conditions in rat renal mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2897–905. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fine LG, Norman JT. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: from hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2008;74:867–72. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]