Abstract

Rolling leukocytes are exposed to different adhesion molecules and chemokines. Neutrophil rolling on E-selectin induces integrin αLβ2-mediated slow rolling on intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by activating a phospholipase C (PLC)γ2- and a separate phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)γ-dependent pathway. E-selectin-signaling cooperates with chemokine signaling to recruit neutrophils into inflamed tissues. However, the distal signaling pathway linking PLCγ2 (Plcg2) to αLβ2-activation is unknown. To identify this pathway, we used different TAT-fusion-mutants and gene-deficient mice in intravital microscopy, autoperfused flow chamber, peritonitis, and biochemical studies. We found that the small GTPase Rap1 is activated following E-selectin engagement and that blocking Rap1a in Pik3cg−/− mice by a dominant-negative TAT-fusion mutant completely abolished E-selectin mediated slow rolling. We identified CalDAG-GEFI (Rasgrp2) and p38 MAPK as key signaling intermediates between PLCγ2 and Rap1a. Gαi-independent leukocyte adhesion to and transmigration through endothelial cells in inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle were completely abolished in Rasgrp2−/− mice. The physiologic importance of CalDAG-GEFI in E-selectin-dependent integrin activation is shown by complete inhibition of neutrophil recruitment into the inflamed peritoneal cavity of Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with pertussis toxin to block Gαi-signaling. Our data demonstrate that Rap1a activation by p38 MAPK and CalDAG-GEFI is involved in E-selectin-dependent slow rolling and leukocyte recruitment.

Keywords: Rap1a, CalDAG-GEFI, p38, integrin, signalling

Introduction

Leukocyte recruitment into inflamed tissue is tightly regulated. A disturbance of this process leads to a reduced inflammatory response such as seen in leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD). This disease is characterized by a reduced leukocyte recruitment into the tissue and is accompanied by recurrent bacterial infections due to an inappropriate inflammatory response to injury or infection.[1] Overwhelming activation of leukocytes is also associated with tissue damage.[2] Therefore, understanding leukocyte activation and recruitment is of key importance for many diseases.

Leukocyte recruitment into inflamed tissue proceeds in a coordinated sequence of events.[3–5] The first steps of this cascade are mediated by endothelial P- and E-selectin interacting with their counter receptor P-selectin glycoprotein ligand (PSGL)-1 on leukocytes.[5] During the intimate contact of leukocytes with the inflamed endothelium, leukocytes are activated by different stimuli.[5, 6] This process induces integrin activation, arrest, crawling, and subsequently leads to extravasation of leukocytes into inflamed tissue.[5]

Inflamed endothelial cells express P- and E-selectin on the cell surface. Binding of the different selectins to PSGL-1 activates distinct signaling pathways and also leads to different rolling velocities in vivo. E-selectin mediates slower rolling (3–7 μm/s) than P-selectin (20–40 μm/s).[7–9] E-selectin binding to PSGL-1 induces a signaling pathway that ultimately leads to partial LFA-1 activation mediating integrin-dependent slow rolling on ICAM-1.[8–10] PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin induces the phosphorylation of the Src kinase Fgr [8, 11] and the ITAM-containing adaptor proteins DAP12 and FcRγ which likely associate with the tyrosine kinase Syk.[8] PSGL-1 and the activation of Syk are required for E-selectin mediated slow rolling.[9] In neutrophils from Fgr−/− mice and Lyn−/−/Hck−/− mice, E-selectin engagement fails to induce DAP12 and Syk phosphorylation.[8, 11] Similarly, elimination of both DAP12 and FcRγ blocks Syk phosphorylation and slow rolling.[8, 11] The Tec family kinase Bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) is downstream of Syk [11, 12] and regulates two pathways. One is phospholipase (PLC)γ2- and the other phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)γ-dependent.[12]

Following E-selectin engagement, p38 MAPK is phosphorylated and blocking of p38 MAPK by a pharmacologic inhibitor increases the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1 compared to the control group.[9–11] Rolling of isolated human neutrophils on cells transfected with E-selectin and ICAM-1 induces p38 MAPK-dependent adhesion.[13] In the E-selectin-mediated pathway, p38 MAPK is downstream of PLCγ2. However, it is unknown how PLCγ2 connects to LFA-1, the integrin responsible for the reduction of the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1. Blocking LFA-1 by a monoclonal antibody completely abolishes E-selectin mediated slow rolling in vitro and in vivo.[9, 11]

During leukocyte rolling on inflamed endothelium, leukocytes are exposed to chemokines that bind to and activate chemokine receptors on neutrophils.[14] The activation of these G-protein coupled receptors leads to the activation of the phospholipases C (PLC) β2 and PLC β3,[15, 16] whereas E-selectin engagement induces the activation of PLCγ2.[12] PLC isoforms hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate to produce inositol-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. Inositol triphosphate subsequently mobilizes Ca2+ from nonmitochondrial stores.

CalDAG-GEFI is expressed in megakaryocytes, platelets, and neutrophils as well as in neurons.[17, 18] CalDAG-GEFI is a member of the CalDAG-GEF/RasGRP family of intracellular signaling molecules and has binding sites for calcium and diacylglycerol as well as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain important for the activation of Rap GTPases. The Rap family consists of two Rap1 genes and two Rap2 genes, with Rap1A and Rap1B being the major isozymes expressed in neutrophils and platelets, respectively.[19, 20] Platelets and neutrophils deficient in CalDAG-GEFI are characterized by impaired activation of Rap1 and of β1, β2, and β3 integrins, both in vitro and in vivo.[17, 21] Consequently, Rasgrp2−/− mice are characterized by a defective inflammatory response and markedly impaired hemostasis.[17, 21] Neutrophil recruitment into the peritoneal cavity following thioglycollate injection was almost completely abolished in Rasgrp2−/− mice,[21] which led us to hypothesize that not only GPCR signaling but also selectin-mediated signaling may be disturbed. To test this, we used a series of dominant-negative, constitutively-active or wild-type Rap1 peptides (ref) that were introduced into neutrophils as TAT fusion peptides (ref).

The present study was designed to uncover the signaling pathway downstream of PLCγ2 leading to integrin activation following E-selectin engagement. Using ex vivo flow chamber assays, in vivo inflammation experiments, and in vitro phosphorylation assays with untreated and TAT-fusion mutants pretreated neutrophils from gene-deficient mice and WT mice, we demonstrate that Rap1a activation by p38 MAPK and CalDAG-GEFI is involved in E-selectin mediated slow leukocyte rolling.

Results

Rap1a is involved in E-selectin mediated slow rolling

Activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) on neutrophils leads to an increase of the intracellular calcium concentration and Rap1 activation.[21] In order to test whether Rap1 is also activated following PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin, we investigated Rap1 activation, i.e., the exchange of GDP for GTP [22, 23] in response to E-selectin engagement without chemokine stimulation., Cell lysates were treated with GTPγS to activate the endogenous Rap1 or treated with GDP to inactivate Rap1. A strong signal for Rap1 was detected by Western blotting using GTPγS-treated cell lysate, while no signal was detected when GDP-treated cell lysate was used (Figure 1A). We detected no activated Rap1 in lysates of resting WT neutrophils. Following stimulation of WT neutrophils with E-selectin under shear, Rap1 activation was significantly elevated after 1 minute and a further increase of Rap1 activation was observed after 5 minutes (Figure 1B+C). E-selectin mediated Rap1 activation was weaker than GPCR triggered Rap1 activation induced by LTB4 as a positive control (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Rap1a is involved in E-selectin mediated slow rolling.

(A) Bone-marrow-derived neutrophils from WT mice were lysed, treated with GTPγS (activator) or GDP (inactivator), and then purified using GST-RalGDS-RBD. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using a specific anti-Rap1 antibody. (B) Bone-marrow-derived neutrophils from WT mice were plated for different time intervals in multiwell plates with or without E-selectin coating, after which lysates were prepared. Western blots of activated Rap1 (affinity-precipitated Rap1-GTP) demonstrate Rap1 activation following E-selectin stimulation. Results are representative of 4 individual experiments. (C) Rap-1-GTP normalized to Rap1-GTP in unstimulated WT neutrophils (n=4). (D) Rolling velocities of reconstituted Lys-M-GFP+ leukocytes and Pik3cg−/− leukocytes pretreated with either wild type Rap1a TAT-peptides (Rap1-WT) or blocking Rap1a TAT-peptides (Rap1-DN) in inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle of Lys-M-GFP+ mice and WT mice. The reconstituted cells were pretreated with PTx, and the mice were pretreated with anti–P-selectin mAb. Average rolling velocity of leukocytes presented as mean ± SEM. (D) Rolling velocities of reconstituted Plcg2−/− leukocytes pretreated with either wild type Rap1a TAT-peptides (Rap1-WT) or constitutively active Rap1a TAT-peptides (Rap1-CA) in inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle of Lys-M-GFP+ mice. The reconstituted cells were pretreated with PTx, and the mice were pretreated with anti–P-selectin mAb. Average rolling velocity of leukocytes presented as mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05. * P < 0.05 vs. other groups.

In order to test whether Rap1a is involved in E-selectin mediated slow rolling, we blocked Rap1a by using dominant-negative Rap1a TAT-fusion mutants in WT leukocytes and investigated the rolling velocity of reconstituted leukocytes in postcapillary venules of the inflamed cremaster muscle (Figure 1D). Blocking Rap1a in WT neutrophils partially elevated the rolling velocity in vivo. We previously showed that the E-selectin-dependent integrin activation pathway splits into a PLCγ2- and PI3Kγ-dependent arm downstream of Btk.[12] When we blocked Rap1a in Pik3cg−/− neutrophils, E-selectin was unable to induce LFA-1-dependent slow rolling (Figure 1D). These data demonstrate that Rap1 is activated following E-selectin engagement and suggests that Rap1a is involved in the PLCγ2-dependent signaling pathway.

Furthermore, we incubated Plcg2−/− neutrophils with either Rap1a-WT or Rap1a-CA peptides (ref) and looked for the rolling velocity in vivo. The average rolling velocity of Plcg2−/− neutrophils pretreated with Rap1a-WT peptides in vivo was 5.6 ± 0.6 μm/s. Treating Plcg2−/− neutrophils with Rap1a-CA peptides reduced the rolling velocity compared to Plcg2−/− neutrophils pretreated with Rap1-WT peptides (Figure 1E).

Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils have impaired E-selectin mediated slow rolling

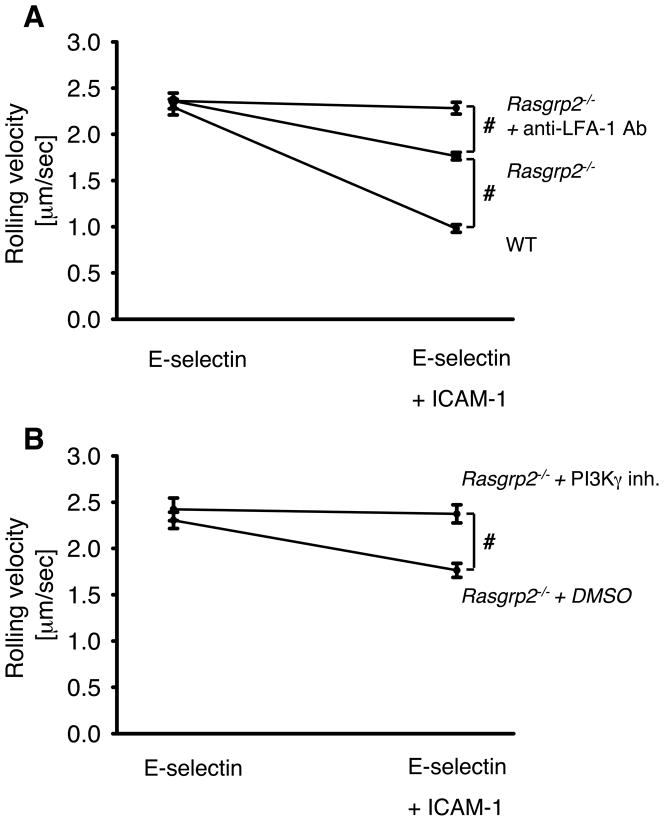

CalDAG-GEFI, encoded by the Rasgrp2 gene, is a major exchange factor for Rap1 (ref). To test whether CalDAG-GEFI is involved in E-selectin–mediated slow rolling, we investigated the rolling velocity of neutrophils from WT mice and Rasgrp2−/− mice in an autoperfused flow chamber.[8, 9] The advantage of this system is that neutrophils can be investigated in whole blood without cell isolation procedures that may activate the cells.[24–26] As previously demonstrated,[8, 9] WT neutrophils show an LFA-1-dependent reduction of the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1 compared to E-selectin alone.[8, 9] The rolling velocity of neutrophils from Rasgrp2−/− mice and WT mice on E-selectin alone was similar (Figure 2A). Neutrophils from WT mice showed a reduction of the rolling velocityon E-selectin plus ICAM-1 (Figure 2A). Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils also showed a reduced rolling velocity on E-selectinplus ICAM-1, but the reduction was significantly less compared to WT neutrophils (Figure 2A). To test whether Rasgrp2−/− neutrophil slow rolling still involved LFA-1, we blocked the β2-integrin LFA-1 by a monoclonal antibody in Rasgrp2−/− mice. Following blocking of LFA-1 in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils, the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1 increased to the level seen on E-selectin alone (Figure 2A). This is similar to the effect seen in WT neutrophils [9] showing that some LFA-1 still becomes activated in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils following E-selectin engagement. Blocking PI3Kγ in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils by a specific pharmacological inhibitor significantly elevated the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1 in the flow chamber above that seen for untreated Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils (Figure 2B). This suggests that CalDAG-GEFI, similar to Rap1a, is involved in the PLCγ2-dependent, but not PI3Kγ-dependent, signaling pathway.

Figure 2. Elimination of CalDAG-GEFI impairs E-selectin mediated slow rolling.

(A) Carotid cannulas were placed in WT mice (n=3) and Rasgrp2−/− mice (n=3) and connected to autoperfused flow chambers. The wall shear stress in all flow chamber experiments was 5–6 dynes/cm2. (B) Rolling velocity of Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils on E-selectin alone or E-selectin/ICAM-1 of either PI3kγ-inhibitor (define molecule)- or DMSO-pretreated mice. Average rolling velocity of neutrophils on E-selectin (left) and E-selectin/ICAM-1 (right) presented as mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05.

CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK are located in the PLCγ2-dependent signaling pathway

Following GPCR engagement, activation of phospholipase C with the subsequent production of second messengers (IP3 and DAG) and intracellular calcium increase is required for CalDAG-GEFI activation.[18] We recently showed that PLCγ2 is required for IP3 production following E-selectin engagement and E-selectin-mediated slow rolling.[12] Blocking of PLC by incubating whole blood with the PLC inhibitor U73122 increased the rolling velocity on E-selectin and ICAM-1 in autoperfused flow chamber experiments (Figure 3A). However, incubation of blood from Rasgrp2−/− mice with the PLC inhibitor U73122 did not further affect the rolling velocity of neutrophils on E-selectin plus ICAM-1 compared to blood from Rasgrp2−/− mice incubated with DMSO (Figure 3B). This data suggests that PLC is upstream of CalDAG-GEFI and may be required to provide calcium for activating CalDAG-GEFI.

Figure 3. CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK are located in the PLCγ2-dependent signaling pathway.

(A) Rolling velocity of WT neutrophils on E-selectin alone or E-selectin/ICAM-1 of either PLC inhibitor (U73122)- or DMSO-pretreated whole blood. (B) Rolling velocity of Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils on E-selectin alone or E-selectin plus ICAM-1 of either U73122- or DMSO-pretreated whole blood. (C) Rolling velocity of Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils on E-selectin alone or E-selectin/ICAM-1 of either p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580)– or DMSO-pretreated mice. Data presented as mean ± SEM from 3 mice. (D) (D) Whole human heparinized blood was treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10μM for 30 minutes at RT) or SB203580 (10μM) plus anti–LFA-1 antibody (10 μg/mL for 20 minutes at RT), then perfused through flow chambers coated with E-selectin with or without ICAM-1. Average rolling velocity of neutrophils on E-selectin (left) and E-selectin/ICAM-1 (right) is presented as mean ± SEM (n=3). (E) Whole human blood was treated with either Rap1-WT or Rap1-DN peptides (1μM for 30 minutes at RT), then perfused through flow chambers coated with E-selectin with or without ICAM-1. Average rolling velocity of neutrophils on E-selectin (left) and E-selectin/ICAM-1 (right) is presented as mean ± SEM (n=3). (F) HL-60 cells transfected with either siRNA specific for CalDAG-GEFI or a non-silencing control sequence were perfused through flow chambers coated with E-selectin and isotype antibody or KIM127 for 2 minutes at 5.94 dyn/cm2. The number of adherent cells per one representative field of view was determined. Data are from 3 experiments. #P < 0.05.

Following E-selectin engagement, p38 MAPK is phosphorylated and participates in neutrophil slow rolling and adhesion.[8, 9, 11–13, 27, 28] Inhibition of p38 MAPK by a pharmacologic inhibitor reduces E-selectin mediated slow rolling.[9, 11] However, blocking p38 MAPK by incubating blood from Rasgrp2−/− mice with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 did not further increase the rolling velocity on E-selectin alone or E-selectin and ICAM-1 in the autoperfused flow chamber (Figure 3C). These data in addition to the fact that p38 MAPK phosphorylation is absent in Plcg2−/− neutrophils after E-selectin engagement[12] suggest that p38 MAPK is involved in the PLCγ2-CalDAG-GEFI-dependent pathway.

To investigate the physiological relevance of our findings, we performed flow chamber assays with human neutrophils and with a human granulocytic cell line (HL-60).[10]. To determine whether p38 MAPK, Rap1a, and CalDAG-GEFI are involved in selectin-mediated integrin activation, we blocked p38 MAPK by an inhibitor (Figure 3D) and Rap1a by a dominant negative Tat-peptide (Figure 3E) and determined the rolling velocity of human neutrophils in whole blood on E-selectin alone and E-selectin and ICAM-1. The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 partially inhibited slow rolling on E-selectin and ICAM-1 (Figure 3D). As expected, adding an LFA-1 blocking mAb to SB203580-treated neutrophils in whole blood completely restored their rolling velocity to the level seen on E-selectin alone (Figure 3D), demonstrating that the p38 pathway is only partially involved in slow rolling. Blocking Rap1a also partially inhibited slow rolling on E-selectin and ICAM-1 (Figure 3E).

In separate experiments, we investigated whether CalDAG-GEFI is involved in selectin-mediated integrin activation, using an immobilized reporter assay as described previously.[10] Down-regulation of CalDAG-GEFI in HL-60 cells by using siRNA (data not shown) inhibited neutrophil accumulation when KIM127 was co-immobilized with E-selectin (Figure 3F), confirming that CalDAG-GEFI is indeed necessary for integrin activation.

CalDAG-GEFI is involved in E-selectin mediated slow rolling in vivo

To test whether Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils show the same defect in slow rolling on E-selectin and ICAM-1 in vivo, we conducted intravital microscopy on mixed chimeric mice. Lethally irradiated WT mice received bone marrow cells from wild-type LysM-GFP+ mice [29] and GFP-negative Rasgrp2−/− mice mixed in a ratio of 1:1. After blocking P-selectin (to limit our observations to E-selectin) and Gαi-signaling (to block chemokine signaling), leukocyte rolling was analyzed in TNF-α-treated venules of the cremaster muscle. The advantage of this system is that leukocytes from gene-targeted mice and WT mice can be directly compared under the same hemodynamic conditions in the same venules. The average rolling velocity of Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes (6.3 ± 1.0 μm/s) in vivo was significantly elevated compared to WT leukocytes (4.2 ± 0.7 μm/s, p < 0.05, Figure 4A). Blocking LFA-1 by a monoclonal antibody further increased the rolling velocity of Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes to a level seen in wild-type mice following antibody-blockade of LFA-1 or both, Mac-1 and LFA-1 (Figure 4A).[9] The mean blood flow velocity and the wall shear rate in these venules were 3.5 ± 0.3 mm/s and 2,100 ± 150 s−1, respectively.

Figure 4. CalDAG-GEFI is involved in E-selectin mediated slow rolling in vivo.

(A) Mixed chimeric mice were generated by injecting bone marrow cells from Rasgrp2−/− mice and LysM-GFP+ WT mice into lethally irradiated WT mice. Cumulative histogram of rolling velocity of 120 GFP+ leukocytes (wild-type, open circle), 120 GFP− leukocytes (Rasgrp2−/−, filled triangle), and 120 Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with a blocking LFA-1 antibody (Rasgrp2−/− + anti-LFA-1-antibody, open triangle) in inflamed cremaster muscle venules of mixed chimeric mice (n=4) treated with PTx and a monoclonal blocking P-selectin antibody. Insert: Mean ± SEM. #P<0.05. (B) Rolling velocities of reconstituted Lys-M-GFP+ leukocytes and Rasgrp2−/−- leukocytes pretreated with wild-type (WT) or constitutive-active (CA) Rap1a TAT-peptides in inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle of Lys-M-GFP+ mice and WT mice. The reconstituted cells were pretreated with PTx, and the mice were pretreated with anti–P-selectin mAb. Average rolling velocity of leukocytes presented as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 vs. other groups. (C) Rap1a is involved in L-selectin clustering in rolling leukocytes. Wild-type leukocytes pretreated with either Rap1a-WT or Rap1a-DN peptides were injected in TNF-alpha treated mice before analysis of L-selectin redistribution by intravital microscopy. Results are derived from the analysis of three mice per group. #P<0.05.

In order to test whether Rap1a is activated in Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes following E-selectin engagement, we added a gain-of-function in vivo experiment. We treated Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes with PTx and either wild-type (WT) Rap1a TAT peptides or constitutive-active (CA) Rap1a TAT peptides and injected the cells in TNF-α pretreated LysM-GFP+-mice that were also treated with an anti-P-selectin antibody. Two hours after TNF-α injection, the rolling velocity of GFP−-cells (Raspgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with the TAT-peptides) were measured in the microcirculation of the cremaster. Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with a WT-Rap1a construct showed an elevated rolling velocity compared to WT leukocytes pretreated with the same construct (Figure 4B). However, Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with a CA-Rap1a TAT-construct showed a reduced rolling velocity compared to Rasgrp2−/− leukocytes treated with the WT-Rap1a construct (Figure 4B).

Previous studies have shown that the ligation of E-selectin ligands triggers p38 MAPK-dependent polarization of L-selectin and PSGL-1 on mouse and human neutrophils.[13, 30, 31] To determine whether Rap1a is also involved in the polarization of L-selectin on mouse neutrophils following E-selectin engagement, we assessed in real time L-selectin distribution on rolling leukocytes by using fluorescence video microscopy. We observed that a large fraction of rolling WT leukocytes pretreated with Rap1a-WT peptides exhibited L-selectin polarization (Figure 4C). Inhibition of Rap1a by using a dominant negative peptide significantly reduced L-selectin redistribution on rolling leukocytes (Figure 4C). These results indicate that Rap1a is involved in E-selectin-mediated redistribution of L-selectin on rolling leukocytes in vivo.

PLCγ2 is upstream of CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK and both molecules are involved in Rap1 activation

To test whether the activation of Rap1 is affected by PLC blockade, we performed a Rap1 activation assay with untreated or U73122 (PLC inhibitor) pretreated WT neutrophils (Figure 5A). After blocking PLC in WT mice, Rap1 is no longer activated after stimulation with E-selectin (Figure 5A). Rap1 also fails to be activated in Plcg2−/− neutrophils (Figure 5B), Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils (Figure 5C), and WT neutrophils pretreated with a pharmacological inhibitor of p38 MAPK (Figure 5D) following E-selectin engagement. In order to test whether Rap1 is located in the PI3Kγ-dependent signaling pathway, we looked for Rap1 activation in Pik3cg−/− neutrophils after stimulation with E-selectin. Rap1 activation was not different between WT and Pik3cg−/− neutrophils following stimulation with E-selectin (Figure 5E). Stimulation of neutrophils from WT mice and Rasgrp2−/− mice with immobilized E-selectin induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 5F), which was blocked in neutrophils pretreated with the PLC inhibitor (Figure 5G). These data in combination with the autoperfused flow chamber data suggest that PLCγ2, CalDAG-GEFI, and p38 MAPK are located upstream of Rap1 and that p38 MAPK activation does not require CalDAG-GEFI after E-selectin engagement.

Figure 5. PLCγ2 is upstream of CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK and both are involved in Rap1 activation.

Bone marrow–derived neutrophils from WT mice (untreated or pretreated with different inhibitors: phospholipase C: U73122, p38 MAPK: SB203580), Pik3cg−/− mice, Plcg2−/− mice, and Rasgrp2−/− mice were plated on uncoated (unstimulated) or E-selectin–coated wells, and then lysates were prepared. (A-C) Total Rap1 and GTP-bound Rap1 protein levels were measured in untreated or pretreated neutrophils from WT mice (A, untreated or pretreated with a phospholipase inhibitor (U73122)), Plcg2−/− mice (B), and Rasgrp2−/− mice (C) after stimulation with E-selectin. Representative blots from 3 independent experiments are shown. (D) Total Rap1 and GTP-bound Rap1 protein levels were measured in unstimulated and stimulated neutrophils from WT mice after inhibiting p38 MAPK (I, SB203580, 10μM). Representative blots from 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Total Rap1 and GTP-bound Rap1 protein levels were measured in unstimulated and stimulated neutrophils from Pik3cg−/− mice. Representative blots from 3 independent experiments are shown. (F+G) Bone-marrow-derived neutrophils from WT mice (untreated or pretreated with a phospholipase inhibitor (U73122)) and Rasgrp2−/− mice were plated in multiwell plates with or without E-selectin coating for 10 minutes, after which lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with antibody to phosphorylated p38 MAPK (phospho-p38) or total p38. Representative blots from 3 independent experiments are shown.

Gαi-independent leukocyte adhesion, transmigration, and recruitment are defective in Rasgrp2−/− mice

Leukocyte adhesion to and transmigration through inflamed endothelium of the cremaster muscle as well as neutrophil recruitment into the peritoneal cavity after thioglycollate injection is promoted by E-selectin– and chemokine-dependent pathways.[12]

Transition from leukocyte rolling to firm adhesion after TNF-α pretreatment is mediated in an overlapping fashion by E-selectin- and CXCR2-signaling.[32] Leukocyte adhesion in the inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle was only investigated in PTx-pretreated mice, because CXCR2-mediated leukocyte arrest is completely abolished in Rasgrp2−/− mice (data not shown). In contrast to WT mice, blocking of G-protein–coupled receptor signaling in Rasgrp2−/− mice significantly reduced leukocyte adhesion after TNF-α application (Figure 6A). Microvascular parameters (vessel diameters, centerline velocities, wall shear rates) were similar between the groups (data not shown).

Figure 6. Gαi-independent leukocyte adhesion, transmigration and recruitment is defective in Rasgrp2−/− mice.

All mice were treated with pertussis toxin (PTx) to block Gαi-signaling. (A) Numbers of adherent cells per square millimeter in murine cremaster muscle venules. The cremaster muscle was exteriorized 2 hours after intrascrotal injection of 500 ng TNF-α in WT and Rasgrp2−/− mice. (B) Number of extravasated leukocytes in inflamed cremasteric venules of WT (n=3) and Rasgrp2−/− mice (n=3) per 1.5 × 104 μm2 tissue area. The measurements were performed 2 hours after intrascrotal TNF-α injection. (C+D) Representative reflected light oblique transillumination microscopic pictures of cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of PTx pretreated WT mice (C) and Rasgrp2−/− mice (D) 2 h after TNF-α application. Demarcations on each side of the venule determine the areas in which extravasated leukocytes were counted. Scale bar equals 50 μm. (E) Neutrophil influx into the peritoneal cavity 8 hrs after 1 ml injection of 4% thioglycollate into mixed chimeric mice generated by injecting bone marrow from WT mice and Rasgrp2−/− mice into lethally irradiated WT mice. After 6 weeks, , mice received 4μg PTx i.v. to block Gαi-signaling followed bye thioglycollate injection. Migration efficiency was calculated (number of recruited neutrophils/number of neutrophils in the blood). Data presented as mean ± SEM from 5 mice. #P < 0.05.

To investigate the contribution of CalDAG-GEFI signaling to leukocyte transmigration, we visualized extravasated leukocytes in the cremaster muscle using reflected-light oblique transillumination(RLOT) microscopy.[12] WT mice treated with 4 μg PTx viatail vein injection before intrascrotal injection of 500 ngTNF-α showed 11 ±3 extravasated leukocytes per 1.5 × 104 μm2. However, the treatment of Rasgrp2−/− mice with PTx caused a significant reduction in leukocyte extravasation (4 ± 1/1.5 × 104 μm2, Figure 6B). Representative reflected light oblique transillumination microscopic images of PTx pretreated WT mice and Rasgrp2−/− mice 2 h after TNF-α application are shown in Figure 6C and D, respectively. These data suggest that the E-selectin–mediated pathway is defective in CalDAG-GEFI-deficient leukocytes.

The injection of thioglycollate into the peritoneal cavity induces neutrophil recruitment, which is promoted by E-selectin- and chemokine-dependent pathways.[8, 9, 32] To investigate the physiological importance of CalDAG-GEFI in a model of acute inflammation, neutrophil recruitment in thioglycollate-induced peritonitis was investigated in mixed chimeric mice reconstituted with bone marrow cells from Rasgrp2−/− mice and Lys-M-GFP+ mice. To selectively focus on the E-selectin pathway, the mice were pretreated with PTx [32] in order to block Gαi-signaling. The calculated migration efficiency (number of recruited neutrophils/number of neutrophils in the blood) demonstrates that the recruitment of Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils was reduced by over 90% compared to WT neutrophils (Figure 6E).

Discussion

CalDAG-GEFI is involved in G-protein coupled receptor-mediated Rap1 activation and β2-integrin-dependent neutrophil arrest.[21] In addition to chemokine-triggered arrest, neutrophils show partial LFA-1 activation and slow rolling when interacting with E-selectin. In this study, we demonstrate that Rap1 is activated following E-selectin engagement and that CalDAG-GEFI-mediated Rap1a activation is involved in E-selectin-mediated slow leukocyte rolling. Knockout and inhibitor studies demonstrate that CalDAG-GEFI is downstream of PLCγ2 following E-selectin engagement. We also show that p38 MAPK, Rap1a, and CalDAG-GEFI are involved in selectin-mediated integrin activation in human neutrophils. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK is dependent on PLCγ2, but not on CalDAG-GEFI. Rasgrp2−/− mice had a reduced Gαi-independent leukocyte adhesion to and transmigration through endothelial cells in inflamed postcapillary venules of the cremaster. Gαi-independent neutrophil recruitment into the inflamed peritoneal cavity was reduced in Rasgrp−/− mice, demonstrating the functional relevance of our findings.

We recently showed that PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin induces activation of the Src kinase Fgr and phosphorylation of ITAM-containing adaptor proteins, which in turn associate with Syk.[8] Following E-selectin engagement, Bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) is phosphorylated in a Syk-dependent manner,[11, 12] and the signalling pathway downstream of Btk divides into a PLCγ2- and PI3Kγ-dependent pathway.[12] In other signaling pathways, activation of phospholipase C induces the production of second messengers and subsequently activates Rap1 in a CalDAG-GEFI-dependent manner.[33, 34] However, the PLC-CalDAG-GEFI-Rap1-pathway has different functions in different cell types and signalling pathways. Following stimulation of T-cells with SDF-1 or neutrophils with LTB4, β2-integrin activation is completely dependent on the activation of Rap1 by CalDAG-GEFI.[21, 33] This is functionally relevant, because elimination of CalDAG-GEFI completely abolished chemokine-induced lymphocyte adhesion to ICAM-1 [33] and neutrophil arrest in vivo.[21] However, PAR4-induced αIIβ3-activation in platelets requires CalDAG-GEFI and protein kinase C, which act synergistically on integrin activation.[34] All the aforementioned signalling pathways have in common that they are completely PLC-dependent. In contrast to the aforementioned signalling pathways, E-selectin mediated slow leukocyte rolling is only partially PLC-dependent. Our results demonstrate that PLCγ2 is involved in E-selectin-mediated slow rolling and likely provides the substrates for the activation of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK, which subsequently activates Rap1 and the β2-integrin LFA-1. Furthermore, the flow chamber and intravital microscopy experiments suggest that LFA-1 activation is partially blocked in Rasgrp2−/− mice. However, due to the lack of reporter antibodies in the murine system, we are not able to distinguish whether LFA-1 affinity or valency regulation is perturbed in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils. Elimination of CalDAG-GEFI partially reduces slow neutrophil rolling, but completely abolishes Gαi-independent leukocyte adhesion and transmigration as well as neutrophil migration into the peritoneal cavity. Inhibiting PI3Kγ in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils or blocking Rap1a in Pik3cg−/− neutrophils completely abolished E-selectin mediated slow rolling, suggesting that the PLCγ2- and PI3Kγ-dependent pathways may use different signalling molecules to fully mediate αLβ2-integrin-dependent E-selectin-induced slow leukocyte rolling. Pharmacologic inhibition of PLC in WT and Rasgrp2−/− mice and the use of Plcg2−/− neutrophils suggest that PLCγ2 is upstream of Rap1 which is activated by CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK. Although we treated neutrophils with different inhibitors and peptides, which may activate these cells, we found no evidence that the used components disturb the rolling behaviour of neutrophils.

Blocking of p38 MAPK in WT mice by a pharmacological inhibitor partially elevated the rolling velocity on E-selectin/ICAM-1 [9] and reduced E-selectin mediated adhesion of isolated human neutrophils to L cells expressing E-selectin and ICAM-1.[13] A recently published study demonstrated that E-selectin mediates the redistribution of PSGL-1 and L-selectin to a major pole on slowly rolling leukocytes through p38 MAPK signaling.[30] The data showing that p38 MAPK phosphorylation is intact in Rasgrp2−/− neutrophils and inhibiting p38 MAPK blocks Rap1 activation suggest that p38 MAPK is either upstream of CalDAG-GEFI or that the signaling pathway downstream of PLCγ2 divides into two branches. Both CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK are involved in Rap1 activation.

The distal signaling pathway elicited by GPCR has similarities with the E-selectin-mediated signaling pathway. The binding of a chemoattractant to its receptor induces the activation of the associated G-protein, which dissociates into the GTP-bound Gα-subunit and the Gβγ-complex.[35] The Gβγ-subunit activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)γ and phospholipase C (PLC) β2 and PLC β3.[15, 16] PLC hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to produce IP3 and diacylglycerol.[6] IP3 mobilizes Ca2+ from nonmitochondrial stores. Ca2+ and diacylglycerol bind to and activate CalDAG-GEFI, which subsequently activates Rap1 and β2-integrins.[21] The LTB4- and CXCR2-induced arrest is totally CalDAG-GEFI dependent (data not shown),[21] whereas LFA-1 activation following E-selectin engagement is only partially CalDAG-GEFI-dependent. These data together with the present data suggest that the GPCR signaling pathway merges with the E-selectin mediated pathway at the stage of CalDAG-GEFI, but an additional CalDAG-GEFI-independent pathway is also triggered by E-selectin engagement.

Elimination of CalDAG-GEFI abolishes integrin-dependent adhesion of leukocytes following GPCR engagement [21] and partially blocks E-selectin mediated slow rolling. However, the recruitment of neutrophils into the inflamed peritoneal cavity of PTx-treated mice is almost completely abolished. The reduction of neutrophil recruitment in Rasgrp2−/− mice is quantitatively similar to the reduction seen in PTx-treated Syk−/− chimeric mice,[9] Tyrobp−/−Fcrg−/− mice,[8] or Plcg2−/− chimeric mice.[12] This data demonstrate the physiological relevance of CalDAG-GEFI in the GPCR- and E-selectin mediated signaling pathway.

The observed role of PLCγ2 in CalDAG-GEFI, and p38 MAPK activation, and E-selectin mediated slow rolling suggests a possible role for calcium and calcium-dependent signaling molecules. Indeed, intracellular calcium levels increase following E-selectin engagement.[36] Different calcium-dependent signaling molecules including some isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) and the RasGRP family of exchange factors may be involved in activating RAS family GTPases.[37] Further downstream, talin and kindlins may directly interact with β2-intergins and modulate their affinity.[38, 39]

In summary, our study establishes that CalDAG-GEFI- and p38 MAPK-mediated Rap1a activation is involved in E-selectin mediated partial LFA-1 activation and slow rolling in vitro and in vivo. This signaling pathway is relevant for neutrophil recruitment in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Animals and bone marrow chimeras

Eight to 12 week-old C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), Rasgrp2−/− mice,[17, 21] Lys-M-GFP+ mice,[29] Plcg2−/− mice,[40] and Pik3cg−/− mice [16] were housed in an SPF facility. The Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Virginia (Charlottesville), LIAI (San Diego, California) and the University of Münster (Germany) approved all animal experiments. Mixed chimeric mice were generated by performing bone marrow transplantation as described previously.[8, 41] Briefly, bone marrow cells isolated from Rasgrp2−/− mice and Lys-M-GFP+ mice were mixed and unfractionated cells were injected intravenously into lethally irradiated mice. Experiments were performed 6–8 weeks after bone marrow transplantation.

Rap1A TAT-fusion mutants

The G12V mutation (constitutive active, CA) and S17N mutation (dominant negative, DN) were introduced into the Ras family small GTP binding protein Rap1A (RAP1A00000, wild type, WT) via the Quickchange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The TAT-fusion mutants have been generated as described previously.[42]

Intravital microscopy

In order to investigate E-selectin mediated slow rolling, adhesion, and transmigration in vivo, mice received TNF-α (500 ng intrascrotally, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and PTx (4 μg i.v., Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) 2 h before the preparation of the cremaster muscle.[8] Mice were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (125 mg/kg, Sanofi Winthrop Pharmaceuticals, USA) and xylazine (12.5 mg/kg, Tranqui Ved, Phonix Scientific, USA) and the cremaster muscle was prepared for intravital imaging as previously described.[8, 9] Intravital microscopy was performed on an upright microscope (Axioskop; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with a 40 × 0.75 NA saline immersion objective. Leukocyte rolling velocity, and leukocyte adhesion were determined by transillumination intravital microscopy, whereas leukocyte extravasation was investigated by reflected light oblique transillumination microscopy as previously described.[12] Recorded images were analyzed off-line using ImageJ and AxioVision (Carl Zeiss) software. Leukocyte rolling flux fraction was calculated as percent of total leukocyte flux. Emigrated cells were determined in an area reaching out 75 μm to each side of a vessel over a distance of 100 μm vessel length (representing 1.5 × 104μm2 tissue area). The microcirculation was recorded using a digital camera (Sensicam QE, Cooke, Germany). Postcapillary venules with a diameter between 20–40 μm were investigated. Blood flow centerline velocity was measured using a dual photodiode sensor system (Circusoft Instrumentation, Hockessin, DE). Centerline velocities were converted to mean blood flow velocities as previously described.[9]

In some experiments, the rolling velocity of reconstituted leukocytes were measured as previously described.[11] Briefly, bone marrow leukocytes from Lys-M-GFP+ mice or gene-targeted mice were incubated with TAT-fusion mutants (1μM, 37°C, 30 min) and PTx (200ng/ml, 37°C, 2h), and then injected i.v. 30 minutes after intrascrotal injection of TNF-α. Two hours after TNF-α application, the rolling velocity of the reconstituted leukocytes was measured in postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle by intravital microscopy. In some of these experiments, L-selectin distribution on the surface of rolling cells was analyzed as described previously.[30] Briefly, mice were injected i.v. immediately before recording with 1.74μg/mouse of Alexa-Fluor-594-conjugated L-selectin antibody (clone MEL-14) as well as an Alexa-Fluor-594-conjugated rat IgG antibody. These experiments were performed on an upright microscope (LSM 5 live; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with a saline immersion objective.

FACS analysis was used to show that > 90% of leukocytes took up fluorescence labeled TAT-fusion mutants up and that the uptake of the different used TAT-fusion mutants was similar (data not shown).

Cell culture

The human promyelocytic cell line HL-60 was purchased at ATCC [CCL-240] and was grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine (2 mM), streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and penicillin (100 U/mL). The cells were cultured at 37 °C, in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air.

RNA interference assays

HL-60 cells (2.5 × 106) were transiently transfected with 1–2 μg siRNA specific for CalDAG-GEFI or a non-silencing control sequence [33] using the Nucleofector apparatus (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Eighteen hours post-transfection, cells were processed for flow chamber experiments.

Autoperfused flow chamber

In order to investigate the rolling velocity, we used a previously described flow chamber system.[8, 9, 43] Rectangular glass capillaries (20×200 μm) were filled either with E-selectin (2.5 μg/ml, R&D Systems, MN, USA) alone or in combination with ICAM-1 (2 μg/ml, R&D) for 2 h and then blocked for 1 h using casein (Pierce Chemicals, Dallas, TX, USA). One side of the chamber was connected to a PE 10 tubing (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) and inserted into a mouse carotid artery. The other side of the chamber was connected to a PE 50 tubing and used to control the wall shear stress in the capillary.[8, 9, 43] One representative field of view was recorded for 1 min using an SW40/0.75 objective and a digitalcamera (Sensicam QE, Cooke Corporation, Romulus, MI, USA).

In some experiments, blood was collected by cardiac puncture and incubated with a pharmacologic phospholipase C inhibitor (U73122; 1 μM; Cayman Chemical) or DMSO control for 30 minutes according a previously published protocol.[44]

In some experiments Rasgrp2−/− mice were pretreated with pharmacologic p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580; 2 mg/kg,[9] Biomol International), PI3Kγ inhibitor (#528106, 20 mg/kg,[12] Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or DMSO 1 h prior experiment.

To investigate selectin-mediated integrin activation in human neutrophils or in a promyelocytic cell line (HL-60), we used previously described flow chamber assays.[10] In some experiments, HL-60 cells were transfected with siRNA or whole human blood was incubated with SB203580 (20mM at 37°C for 30 minutes), Rap1a-WT or Rap1-DN peptides (1mM at 37°C for 30 minutes) before perfusion through flow chambers.

Engagement of PSGL-1 with E-selectin

For biochemical assays, bone-marrow derived neutrophils were isolated,[8] suspended in PBS (containing 1 mM each CaCl2 and MgCl2) and left untreated or were pretreated with a pharmacologic phospholipase C inhibitor (U73122; 1 μM; Cayman Chemical), a pharmacologic p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580; 10 μM; Biomol International) or DMSO control for 30 minutes Subsequently the cells were incubated under rotating conditions (65 rpm) for 10 minutes at 37°C on E-selectin coated dishes.[8] Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer [8] and lysates were boiled with sample buffer. Cell lysates were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, immunoblotted using antibodies against p38 MAPK, and phospho-p38 MAPK (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and developed using Amersham’s ECL system (Piscataway, NJ, USA).

In order to investigate Rap1 activation, bone-marrow derived neutrophils were stimulated with E-selectin and immediately lysed with EDTA-free ice-cold lysis buffer.[8] Detection of GTP-bound Rap1 (Rap1-GTP) in PMN lysates was performed with the Rap1 small GTPase immunoblot assay kit from Pierce as described previously.[21] In brief, Rap1-GTP was precipitated from lysates using a GST-RalGDS-RDB fusion protein. Precipitated proteins were separated using a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. To determine the level of total Rap1, a small portion of the cell lysate was mixed with SDS sample buffer and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. Rap1 was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Peritonitis Model

The peritonitis model was performed as described previously.[8, 9] Briefly, peritonitis in mixed chimeric mice was induced by injecting sterile 4% thioglycollate i.p. (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). 2 h before thioglycollate injection, mice received 4 μg PTx i.v. in order to block Gαi-signaling. After 8 h, mice were killed, the peritoneal cavity was washed with 10 mlPBS and the number of leukocytes was counted. Neutrophils were detected by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) based on expression of GFP, CD45 (clone 30-F11), GR-1 (clone RB6-8C5), and 7/4 (clone 7/4, both BD Biosciences-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Neutrophil migration efficiency was calculated by dividing number of recruited neutrophils by the number of neutrophils in the blood.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with with SPSS (version 14.0, Chicago, IL). Differences between thegroups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance, Student-Newman-Keuls test or t-test where appropriate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Katrin Tkotz for technical support and Stefanie Kliche for providing the GST-RalGDS fusion protein for Rap1. This study was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (AZ 428/3-1 to A.Z.), Interdisciplinary Clinical Research Center (IZKF Muenster, Germany, Za2/001/10 to A.Z.), and the NIH (NHLBI POI HL056949 to D.D.W). W.B. was supported by a Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Anderson DC, Springer TA. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency: an inherited defect in the Mac-1, LFA-1, and p150,95 glycoproteins. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:175–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butcher EC. Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell. 1991;67:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarbock A, Ley K. Mechanisms and consequences of neutrophil interaction with the endothelium. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1–7. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunkel EJ, Ley K. Distinct phenotype of E-selectin-deficient mice. E-selectin is required for slow leukocyte rolling in vivo. Circ Res. 1996;79:1196–1204. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarbock A, Abram CL, Hundt M, Altman A, Lowell CA, Ley K. PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin signals through Src kinase Fgr and ITAM adapters DAP12 and FcR gamma to induce slow leukocyte rolling. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2339–2347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarbock A, Lowell CA, Ley K. Spleen tyrosine kinase Syk is necessary for E-selectin-induced alpha(L)beta(2) integrin-mediated rolling on intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Immunity. 2007;26:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuwano Y, Spelten O, Zhang H, Ley K, Zarbock A. Rolling on E- or P-selectin induces the extended but not high-affinity conformation of LFA-1 in neutrophils. Blood. 2010;116:617–624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yago T, Shao B, Miner JJ, Yao L, Klopocki AG, Maeda K, Coggeshall KM, McEver RP. E-selectin engages PSGL-1 and CD44 through a common signaling pathway to induce integrin alphaLbeta2-mediated slow leukocyte rolling. Blood. 2010;116:485–494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller H, Stadtmann A, Van Aken H, Hirsch E, Wang D, Ley K, Zarbock A. Tyrosine kinase Btk regulates E-selectin-mediated integrin activation and neutrophil recruitment by controlling phospholipase C (PLC) gamma2 and PI3Kgamma pathways. Blood. 2010;115:3118–3127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon SI, Hu Y, Vestweber D, Smith CW. Neutrophil tethering on E-selectin activates beta 2 integrin binding to ICAM-1 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Immunol. 2000;164:4348–4358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ley K. Arrest chemokines. Microcirculation. 2003;10:289–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camps M, Carozzi A, Schnabel P, Scheer A, Parker PJ, Gierschik P. Isozyme-selective stimulation of phospholipase C-beta 2 by G protein beta gamma-subunits. Nature. 1992;360:684–686. doi: 10.1038/360684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in inflammation. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crittenden JR, Bergmeier W, Zhang Y, Piffath CL, Liang Y, Wagner DD, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. CalDAG-GEFI integrates signaling for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2004;10:982–986. doi: 10.1038/nm1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Toki S, Canales JJ, Harlan P, Blumenstiel JP, Chen EJ, Bany IA, Mochizuki N, Ashbacher A, Matsuda M, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torti M, Lapetina EG. Structure and function of rap proteins in human platelets. Thromb Haemost. 1994;71:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn MT, Parkos CA, Walker L, Orkin SH, Dinauer MC, Jesaitis AJ. Association of a Ras-related protein with cytochrome b of human neutrophils. Nature. 1989;342:198–200. doi: 10.1038/342198a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergmeier W, Goerge T, Wang HW, Crittenden JR, Baldwin AC, Cifuni SM, Housman DE, Graybiel AM, Wagner DD. Mice lacking the signaling molecule CalDAG-GEFI represent a model for leukocyte adhesion deficiency type III. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1699–1707. doi: 10.1172/JCI30575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bos JL, de Rooij J, Reedquist KA. Rap1 signalling: adhering to new models. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:369–377. doi: 10.1038/35073073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caron E. Cellular functions of the Rap1 GTP-binding protein: a pattern emerges. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:435–440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsyth KD, Levinsky RJ. Preparative procedures of cooling and re-warming increase leukocyte integrin expression and function on neutrophils. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90206-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasser L, Fiederlein RL. The effect of various cell separation procedures on assays of neutrophil function. A critical appraisal. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:662–669. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuijpers TW, Tool AT, van der Schoot CE, Ginsel LA, Onderwater JJ, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ. Membrane surface antigen expression on neutrophils: a reappraisal of the use of surface markers for neutrophil activation. Blood. 1991;78:1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hentzen E, McDonough D, McIntire L, Smith CW, Goldsmith HL, Simon SI. Hydrodynamic shear and tethering through E-selectin signals phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase and adhesion of human neutrophils. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:987–1001. doi: 10.1114/1.1511240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urzainqui A, Serrador JM, Viedma F, Yanez-Mo M, Rodriguez A, Corbi AL, Alonso-Lebrero JL, Luque A, Deckert M, Vazquez J, Sanchez-Madrid F. ITAM-based interaction of ERM proteins with Syk mediates signaling by the leukocyte adhesion receptor PSGL-1. Immunity. 2002;17:401–412. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faust N, Varas F, Kelly LM, Heck S, Graf T. Insertion of enhanced green fluorescent protein into the lysozyme gene creates mice with green fluorescent granulocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2000;96:719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Wild MK, Vestweber D, Frenette PS. Complete identification of E-selectin ligands on neutrophils reveals distinct functions of PSGL-1, ESL-1, and CD44. Immunity. 2007;26:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green CE, Pearson DN, Camphausen RT, Staunton DE, Simon SI. Shear-dependent capping of L-selectin and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 by E-selectin signals activation of high-avidity beta2-integrin on neutrophils. J Immunol. 2004;172:7780–7790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith ML, Olson TS, Ley K. CXCR2- and E-selectin-induced neutrophil arrest during inflammation in vivo. J Exp Med. 2004;200:935–939. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghandour H, Cullere X, Alvarez A, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Essential role for Rap1 GTPase and its guanine exchange factor CalDAG-GEFI in LFA-1 but not VLA-4 integrin mediated human T-cell adhesion. Blood. 2007;110:3682–3690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cifuni SM, Wagner DD, Bergmeier W. CalDAG-GEFI and protein kinase C represent alternative pathways leading to activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 in platelets. Blood. 2008;112:1696–1703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bokoch GM. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood. 1995;86:1649–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaff UY, Yamayoshi I, Tse T, Griffin D, Kibathi L, Simon SI. Calcium flux in neutrophils synchronizes beta2 integrin adhesive and signaling events that guide inflammatory recruitment. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:632–646. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9453-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:546–559. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moser M, Legate KR, Zent R, Fassler R. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science. 2009;324:895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose DM, Alon R, Ginsberg MH. Integrin modulation and signaling in leukocyte adhesion and migration. Immunol Rev. 2007;218:126–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Feng J, Wen R, Marine JC, Sangster MY, Parganas E, Hoffmeyer A, Jackson CW, Cleveland JL, Murray PJ, Ihle JN. Phospholipase Cgamma2 is essential in the functions of B cell and several Fc receptors. Immunity. 2000;13:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarbock A, Singbartl K, Ley K. Complete reversal of acid-induced acute lung injury by blocking of platelet-neutrophil aggregation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3211–3219. doi: 10.1172/JCI29499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolomini-Vittori M, Montresor A, Giagulli C, Staunton D, Rossi B, Martinello M, Constantin G, Laudanna C. Regulation of conformer-specific activation of the integrin LFA-1 by a chemokine-triggered Rho signaling module. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:185–194. doi: 10.1038/ni.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chesnutt BC, Smith DF, Raffler NA, Smith ML, White EJ, Ley K. Induction of LFA-1-dependent neutrophil rolling on ICAM-1 by engagement of E-selectin. Microcirculation. 2006;13:99–109. doi: 10.1080/10739680500466376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zarbock A, Deem TL, Burcin TL, Ley K. Galphai2 is required for chemokine-induced neutrophil arrest. Blood. 2007;110:3773–3779. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]