INTRODUCTION

Currently, an estimated 300,000 children under the age of 18 are involved in military forces or armed rebel groups worldwide. Children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAAFAG), commonly referred to as “child soldiers,” are both boys and girls “who are part of any kind of regular or irregular armed force or armed group in any capacity, including, but not limited to: cooks, porters, messengers and those recruited for sexual purposes and for forced marriage.” [1] During Sierra Leone’s bloody civil war (1991–2002), thousands of children were involved in the Revolutionary United Front (RUF)-- the main rebel group in the war—as well and Civilian Defense Forces (CDF) and the Sierra Leone Army (SLA). [2] The conflict is known for the extremity of its violence and atrocities [3, 4]: tens of thousands of civilians were killed and almost 75% of the population experienced displacement. [2, 5] While some youth joined the conflict voluntarily, many more were forcibly recruited; of these forced recruits, approximately 50% were abducted at age 15 or younger. [6]

In recent years, research has investigated the roles of women and girls in at least 20 conflicts, including the war in Sierra Leone. [6–9] Ethnographic reports indicate that armed groups in Sierra Leone used girls to fulfill multiple roles during their time with fighting forces. [10, 11] While they were frequently abducted for sexual purposes, girls almost always had other military tasks, including combat, laying explosives, portering, and performing domestic tasks. [9, 12] Girls cared for the sick and wounded, served as spies, and even worked in diamond mines for their commanders or so-called “husbands”. [9] Research also documents very high levels of rape and sexual abuse among female CAAFAG. [9, 13] Recent reports from other conflict areas such as the Democratic Republic of Congo indicate that sexual assault is rapidly becoming one of the most common forms of war-related violence. [14]

Research suggests that in the aftermath of war, girls are confronted with gender-specific physical and psychological challenges. Within strongly patriarchal post-conflict societies, female CAAFAG are frequently expected to resume traditional gender roles rather than seek broader opportunities. [10, 15–17] In Sierra Leone, many female CAAFAG were excluded from government Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration programs and a very small fraction of returning girls benefited from education or livelihood packages. [7, 18] Studies have shown that girls work far more hours than boys, have lower literacy rates, and suffer preventable deaths because they lack reproductive health care. [9] Despite a high rate of rape among female CAAFAG, sexual violence is rarely reported due to community stigma and personal sense of shame. [12, 19]

Given these particularly harsh adversities, it is likely that returning female CAAFAG are at greater risk of developing psychological or adjustment problems. Females affected by war-related trauma have demonstrated higher rates of psychosocial distress compared to males [20], and research suggests that females are more vulnerable to depression [21] and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially during adolescence. [22] However, in the handful of existing empirical studies of child soldiers, the relationships between gender, war experiences and post-conflict psychosocial adjustment have not been well-documented. [23–25] For example, Boothby’s 16-year follow-up of a small group (N=39) of Mozambican former CAAFAG involved an all-male sample. [26] Studies documenting the mental health of CAAFAG in Uganda [27] and the Democratic Republic of Congo [28] involved relatively small samples of females or did not disaggregate findings by gender. In a recent study of child soldiers in Nepal, researchers found gender differences in the association between violence exposure and mental health outcomes and postulated that unmeasured, gender-sensitive variables such as rape and stigma, which were not measured, may have played an explanatory role. [25] These findings underscore how sensitivity to gender is critical to understanding war experiences and post-conflict reintegration of child soldiers, and for developing effective interventions. [9, 16, 20, 27]

The aims of this analysis were threefold: (1) to compare the war experiences of male and female CAAFAG, including witnessing of violence, direct involvement in war activities and combat, and experience of rape; (2) to examine the differences between psychosocial outcomes of male and female child soldiers post conflict; (3) to examine the moderating effects of gender on the relationship between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has explored these types of interaction effects between gender and war exposures among a sample of former child soldiers. Hypotheses informed by an examination of existing literature [9–11, 29] anticipated that male CAAFAG would report higher rates of direct involvement in atrocities while girls would report higher rates of rape. It was also expected that females exposed to violence would demonstrate higher levels of psychosocial distress, particularly internalizing problems. [30] Additionally, we anticipated finding the most detrimental psychosocial effects in groups exposed to highly traumatic events (rape and wounding/killing others), and that gender would moderate these effects.

METHODS

Study Cohort and Procedures

This study presents a cross-sectional analysis of data collected in 2004 as part of a larger longitudinal study of Sierra Leonean war-affected youth. This longitudinal study was launched in 2002 by the first author in collaboration with the International Rescue Committee (IRC). In 2002, 260 former child soldiers (11% females and 89% males) completed baseline interviews. Participants were selected from pooled registries of all young people processed through the IRC Interim Care Center (ICC) in Kono district between June 2001 and February 2002, the most active period of demobilization. At follow-up in 2004, 56% (N=146) of the original participants were re-interviewed, as well as a new sample of 127 self-reintegrated former child soldiers (50% females, 50% males), identified by outreach lists compiled by NGOs in the Makeni region. A screening questionnaire was used to confirm that self-reintegrated participants had not received formal reintegration services. All participants were under the age of 18 at time of involvement with the RUF. The 2004 cross-sectional sample was selected for the present gender-focused analysis given its sizeable number of female participants.

The Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical School/Boston Medical Center approved all research protocols. Data for all participants (N=273) were collected through face-to-face interviews conducted by a team of trained Sierra Leonean research assistants monitored by the study PI and IRC staff. Social workers traveled with the research team to respond to serious emotional or physical health needs and make referrals to local service programs.

Instruments and Scales

The study employed a mix of locally-derived measures and standard measures validated for cross-cultural use. [23] All measures were selected and adapted in close consultation with Sierra Leonean staff and community members. Focus groups of youth and adults were used to develop additional questionnaire items and to determine the face validity and cultural relevance of standard measures.

Several independent variables were of interest. A 28-item adapted version of the Child War Trauma Questionnaire (CWTQ) was used to assess individual-level war experiences. Initially developed for Lebanese war-affected youth, [20] the questionnaire was revised to capture the Sierra Leone context; for example, items on bombing and shelling were removed and items on cutting (machete attacks), school raids, and sexual assault were added. War experiences were coded for occurrence versus no occurrence. Following recommendations by Netland [31], Layne [32], and others [20], conceptual grouping (rational approach) was used to derive five war exposure categories: two groupings of conceptually-similar items and three single-item categories of events considered to be particularly detrimental to child mental health (see Table 1). Grouped events included: 1) Witnessing of violence (13 items); and 2) RUF-related abuse and violence/injury (12 items). Single-item categories included: 1) Killing others; 2) Surviving rape/sexual assault; and 3) Death of mother or father.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics, war exposures, and mental health outcomes of the full sample by gender

| Full Sample (N=273) | Males (N=194) | Females (N=79) | P Value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic Characteristic | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age at interview, y | 16.55 (2.61) | 16.69 (2.65) | 16.19 (2.48) | 0.16 |

| Age of abduction, y | 10.60 (2.87) | 10.68 (2.86) | 10.39 (2.89) | 0.47 |

| Years with armed forces, y | 2.69 (2.18) | 2.80 (2.28) | 2.38 (1.88) | 0.18 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Research group | <0.0001 | |||

| ICC reintegrated | 146 (53) | 131 (68) | 15 (19) | |

| Self-reintegrated | 127 (47) | 63 (32) | 64 (81) | |

| Religion | 0.60 | |||

| Christian | 128 (47) | 89 (46) | 39 (49) | |

| Muslim | 145 (53) | 105 (54) | 40 (51) | |

| Literacy | <0.0001 | |||

| Poor | 24 (10) | 8 (5) | 16 (25) | |

| Basic | 130 (55) | 95 (55) | 35 (56) | |

| Moderate | 57 (24) | 49 (28) | 8 (13) | |

| Excellent | 24 (10) | 20 (12) | 4 (6) | |

| Caregiver Now | 0.81 | |||

| Natural mother, father, or both | 152 (56) | 110 (57) | 42 (53) | |

| Siblings | 21 (8) | 16 (8) | 5 (6) | |

| Extended Family | 65 (24) | 41 (21) | 24 (30) | |

| Other Family (Foster, step etc.) | 24 (9) | 18 (9) | 6 (8) | |

| In school at time of interview | 210 (79) | 162 (85) | 48 (63) | <0.0001 |

| War Exposure | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Witnessing of violence | ||||

| Witnessed intimidation, beating or torture, No (%) | 180 (66%) | 129 (66%) | 51 (65%) | 0.76 |

| Witnessed violent physical injury | 116 (42%) | 79 (41%) | 37 (47%) | 0.35 |

| Witnessed violent death | 163 (60%) | 116 (60%) | 47 (59%) | 0.96 |

| Witnessed rape | 65 (24%) | 37 (19%) | 28 (35%) | 0.004 |

| Witnessed bomb/grenade explosion at a close distance | 180 (66%) | 123 (63%) | 57 (72%) | 0.17 |

| Witnessed stabbing, chopping at a close distance | 109 (40%) | 70 (36%) | 39 (49%) | 0.04 |

| Witnessed shooting at a close distance | 194 (71%) | 130 (67%) | 64 (81%) | 0.02 |

| Witnessed massacre of many people at once | 132 (48%) | 91 (47%) | 41 (52%) | 0.45 |

| Witnessed raid of school | 43 (16%) | 28 (14%) | 15 (19%) | 0.35 |

| Witnessed raid of homes | 87 (32%) | 53 (27%) | 34 (43%) | 0.01 |

| Witnessed raid of villages | 156 (57%) | 109 (56%) | 47 (59%) | 0.62 |

| Witnessed amputation | 95 (35%) | 62 (32%) | 33 (42%) | 0.12 |

| Witnessed indiscriminate firing | 170 (62%) | 122 (63%) | 48 (61%) | 0.74 |

| RUF-Related Abuse | ||||

| Being in detention | 92 (34%) | 64 (33%) | 28 (35%) | 0.70 |

| eing chased by armed forces | 122 (45%) | 88 (45%) | 34 (43%) | 0.73 |

| Being kidnapped by armed forces | 137 (50%) | 94 (48%) | 43 (54%) | 0.37 |

| Being arrested by armed forces | 144 (53%) | 100 (52%) | 44 (56%) | 0.53 |

| Recruited and trained by armed forces | 86 (38%) | 65 (42%) | 21 (28%) | 0.03 |

| Being beaten by armed forces | 160 (59%) | 112 (58%) | 48 (61%) | 0.65 |

| Being threatened to be killed | 171 (63%) | 120 (62%) | 51 (65%) | 0.68 |

| Being stabbed or chopped | 22 (8%) | 12 (6%) | 10 (13%) | 0.07 |

| Being shot | 45 (17%) | 32 (16%) | 13 (16%) | 0.99 |

| Being without food for 2 days | 222 (81%) | 157 (81%) | 65 (82%) | 0.80 |

| Being without water for 2 days | 79 (29%) | 46 (24%) | 33 (42%) | 0.003 |

| Being without clothes/shoes for 2 days | 211 (77%) | 144 (74%) | 67 (85%) | 0.06 |

| Forced to take drugs | 93 (34%) | 67 (35%) | 26 (33%) | 0.80 |

| Killing of others | 80 (29%) | 57 (29%) | 23 (29%) | 0.96 |

| Raped/sexually abused by armed forces | 44 (16%) | 9 (5%) | 35 (44%) | <0.0001 |

| Lost mother or father during the war | 75 (27%) | 45 (23%) | 30 (38%) | 0.01 |

| Mental Health Outcome | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) [95% CI] | Mean (SD) [95% CI] | |

| HSCL Anxiety | 20.55 (6.54) | 19.58 (6.65) [18.62 – 20.53] | 22.90 (5.64) [21.63 – 24.17] | 0.0001 |

| HSCL Depression | 30.59 (9.11) | 29.64 (9.22) [28.31 – 30.97] | 32.92 (8.45) [31.00 – 34.84] | 0.008 |

| Hostility | 21.02 (6.05) | 20.49 (6.35) [19.58 – 21.40] | 22.32 (5.06) [21.18 – 23.47] | 0.01 |

| Confidence | 24.02 (4.20) | 24.66 (3.96) [24.10 – 25.23] | 22.37 (4.37) [21.37 – 23.38] | <.0001 |

| Prosocial Attitude | 33.11 (4.88) | 33.75 (4.48) [33.10 – 34.39] | 31.59 (5.47) [30.36 – 32.82] | 0.003 |

T-tests used to evaluate mean differences between male and female participants for continuous variables and χ2 used for categorical data.

In addition, a demographic survey collected information on gender, age, manner of reintegration (DDR-supported vs. self–reintegration), length of abduction, school access, and level of education and literacy. The survey also included a 4-item locally-derived measure assessing families’ socio-economic status in relation to others in the community with responses totaled to provide a continuous measure (Cronbach’s α=0.77).

A series of dependent variables were of interest. Anxiety and depression were assessed using an adapted version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist/SF-25 (HSCL-25). [33] The instrument has been widely used to measure mental health problems among war-affected populations. In this sample, the HSCL-25 demonstrated good internal consistency for depression (Cronbach’s α=0.88) and anxiety sub-scales (Cronbach’s α=0.89). A recommended cut-point used in other war-affected populations (mean cumulative symptom score exceeding 1.75) was applied. [34]

Three additional constructs - hostility, confidence, and prosocial attitudes - were measured using the IRC/Oxford Psychosocial Instrument. This standardized scale was developed in the Krio language to measure psychosocial adjustment in Sierra Leonean child soldiers. [23] The three subscales achieved good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.87 for hostility; α=0.71 for confidence; α=0.81 for prosocial attitudes).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in three stages. First, descriptive statistics were analyzed. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated as descriptive measures; t-tests were used to perform unadjusted comparisons by gender. For categorical data, descriptive statistics were calculated using frequencies and associated percentages. Unadjusted tests of association with gender were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test. Multiple imputation was used for missing values. This approach aims to reduce bias, increase precision, and account for sampling variability across imputations. [35] Imputed datasets were generated using the method of chained equations as implemented in IVEware. [36] All remaining analyses were conducted across imputations and results were combined using the MIANALYZE procedure in SAS software, version 9.2. [37]

Second, multiple linear regression assessed the effect of independent variables - gender and war experiences - on the dependent variables - anxiety, depression, hostility, confidence, and prosocial outcomes. All models were adjusted for socio-demographic variables.

Third, a series of interaction terms examined the moderating effect of gender on the statistically significant relationships between war exposures and psychosocial outcomes. All statistical tests were two-sided and conducted at the α=0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sample’s demographic and socioeconomic characteristics by gender. Females constituted 29% (N=79) of the sample. Eighty-one percent (N=64) of female participants and 32% (N=63) of male participants self-reintegrated without formal assistance; fifty-three percent of the total (N=146) received NGO assistance via ICCs. The average age of abduction was comparable among males (mean=10.68, SD=2.86) and females (mean=10.39, SD=2.89). Males and females reported comparable family placements post-conflict, with the majority of girls (53%) and boys (57%) living with at least one natural parent. In this sample, there was no significant difference between the length of time spent by girls and boys in captivity with fighting forces. Twenty-five percent of girls reported poor reading/writing skills compared to 5% of boys. A significantly smaller proportion of females were attending school at the time of the study.

War Exposures

Assessments revealed that the nature, frequency, and severity of most war-related experiences were similar for male and female CAAFAG (Table 1). Boys and girls reported witnessing similarly high rates of beatings, injuries, torture and violent deaths. Females were just as likely to have witnessed bomb explosions, massacres and indiscriminate firing, and were more likely than males to have witnessed stabbings, shootings and raids of homes (Table 1).

Boys (42%) were more likely than girls (28%) to have been trained as soldiers. Girls and boys experienced almost equally-high rates of abuse by armed groups. Comparable numbers of male and female former child soldiers were beaten, threatened with murder, shot, deprived of food, and forced to take drugs. Contrary to our hypotheses, boys and girls were equally likely to have been involved in injuring or killing others.

Significant differences related to gender were recorded for a few items. More girls reported being without water for longer than two days, and more female CAAFAG reported losing a parent during the war. Significantly higher rates of rape were recorded among girls (44% vs. 5% of boys).

Mental Health Outcomes

Females demonstrated significantly higher scores of depression and anxiety (see Table 1), with many more girls scoring within the clinical range for anxiety (80% vs. 52% of boys) and depression (72% vs. 55% of boys). IRC/Oxford psychosocial instrument scores revealed significantly higher levels of hostility symptoms among females compared to males. Females also reported significantly lower levels of confidence and lower levels of prosocial attitudes.

In multiple regression analyses adjusted for method of reintegration, socio-economic status, age, and school attendance (Table 2), losing a parent was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Killing/injuring others was strongly associated with more severe depression, anxiety and hostility symptoms, while being a victim of rape/sexual abuse was predictive of anxiety and hostility, but not depression. In analyses adjusted for all other factors, gender did not persist as a significant predictor of anxiety, depression or hostility; however, lower confidence levels were predicted by female gender, and higher confidence levels and prosocial attitudes were predicted by school attendance. On average, youth who had survived rape/sexual assault reported higher levels of prosocial attitudes and confidence, adjusting for other factors.

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis of mental health and psychosocial outcomes.

| Variable | Depression^ | Anxiety | Hostility | Confidence | Prosocial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1.35 (−1.57, 4.27) | 1.53 (−0.48, 3.54) | 0.81 (−1.09, 2.70) | −1.65* (−3.00,−0.30) | −0.98 (−2.56, 0.60) |

| Age | 0.32 (−0.14, 0.77) | 0.12 (−0.19, 0.44) | −0.11 (−0.40, 0.18) | 0.20+ (−0.01, 0.41) | 0.12 (−0.12, 0.37) |

| ICC Reintegrated | −0.61 (−1.84, 0.63) | −0.30 (−1.16, 0.56) | −0.39 (−1.19, 0.41) | 0.61* (0.04, 1.18) | 1.11* (0.43, 1.78) |

| Socio-Economic Status (SES)1 | −0.39 (−1.71, 0.92) | −0.24 (−1.16, 0.67) | 0.08 (−0.88, 1.05) | −0.16 (−1.01, 0.68) | −0.38 (−1.56, 0.81) |

| In school | −0.37 (−1.57, 0.82) | −0.18 (−0.99, 0.63) | 0.33 (−0.45, 1.12) | 0.88* (0.34, 1.42) | 1.15** (0.52, 1.78) |

| Years with Armed Forces | 0.29 (−0.20, 0.78) | 0.09 (−0.26, 0.43) | 0.30+ (−0.03, 0.62) | 0.10 (−0.18, 0.37) | 0.02 (−0.29, 0.33) |

| Lost mother or father | 2.83* (0.57, 5.10) | 1.73* (0.14, 3.32) | 0.32 (−1.16, 1.80) | −0.71 (−1.80, 0.38) | −0.55 (−1.82, 0.72) |

| Witnessing of Violence | 0.16 (−1.22, 1.54) | 0.52 (−0.40, 1.45) | 0.50 (−0.50, 1.50) | −0.42 (−1.06, 0.23) | −0.60 (−1.59, 0.39) |

| RUF-Related Abuse† | 0.31 (−0.96, 1.59) | 0.16 (−0.83, 1.16) | 0.02 (−0.90, 0.93) | 0.10 (−0.55, 0.75) | −0.28 (−1.19, 0.63) |

| Killing Others | 5.01*** (2.65, 7.36) | 3.81*** (2.16, 5.46) | 4.78*** (3.25, 6.32) | −0.48 (−1.60, 0.64) | 0.04 (−1.28, 1.35) |

| Sexual Assault/Rape | 2.42 (−0.99, 5.84) | 2.85* (0.45, 5.26) | 2.37* (0.16, 4.59) | 1.87* (0.21, 3.53) | 2.26* (0.27, 4.26) |

| R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | |

| .18 | .23 | .24 | .16 | .16 | |

Statistically significant at P = .05;

Statistically significant at P = .01;

Statistically significant at P <.0001

Values are expressed as β (95% CI).

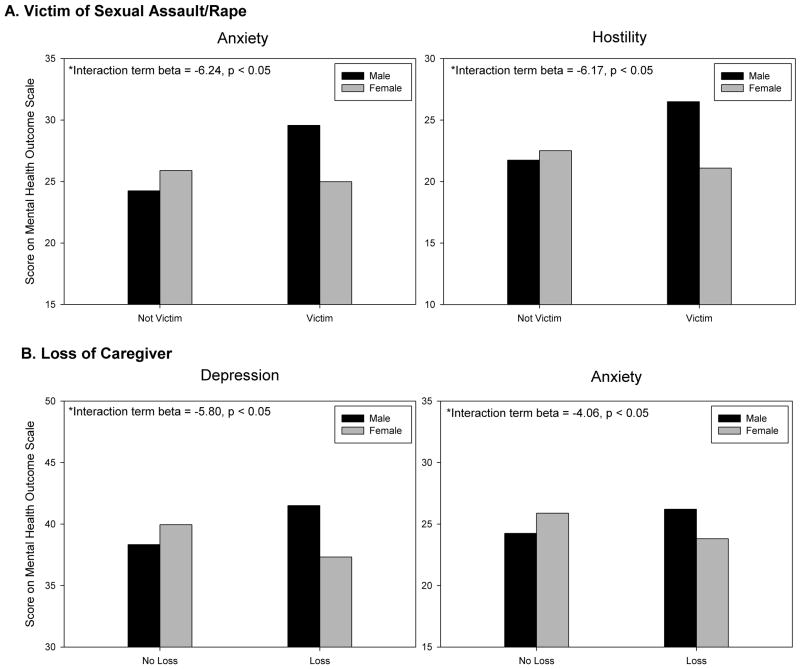

Analyses examining the moderating effects of gender revealed significant associations between gender and rape as a predictor of both anxiety and hostility. Gender also moderated the relationship between losing a caregiver during the war, depression and anxiety.

Figure 1 demonstrates these interaction effects. A smaller percentage of boys experienced rape (5%) or the loss of a caregiver (23%), as compared to girls (44% and 38%, respectively). However, the effect of rape on anxiety and hostility was strong and significant among male child soldiers and did not reach significance among females. Similarly, the loss of a caregiver was associated with elevated anxiety and depression among males but not among females.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Gender and War Exposure on Mental Health Outcome (*p<0.05)

DISCUSSION

This study’s findings challenge the common perception of “child soldiering” as a male-only phenomenon. Girls and boys in our sample experienced comparable levels of exposure to most violent events including participation in front line fighting. At the same time, females reported significantly more instances of rape and sexual abuse, and far more limited access to protective resources such as education. Ethnographic and qualitative reports from post-conflict settings confirm the challenges female CAAFAG face upon returning home. For example, Utas, Persson, and Coulter [29] note that Ugandan and Sierra Leonean men often refuse to marry women associated with armed forces, arguing they are sexually tainted, unpredictable and aggressive. Other research on female CAAFAG documents that high rates of violence exposure and rape among girls are compounded by limited access to protective resources in the post-conflict environment; for instance, McKay and Mazurana [9] note that returning girl soldiers in Mozambique were excluded from reintegration programs because of the government’s concealment of female combatants.

Confirming our second hypothesis, in unadjusted analyses female CAAFAG demonstrated lower levels of positive adjustment and higher levels of depression, anxiety, and hostility. These findings are consistent with previous research on differences observed among male and female war-affected youth in several settings. [20, 22, 25, 38] However, in adjusted regression analyses, the effects of war experiences surpassed the main effects of gender as a significant predictor of most mental health difficulties while female gender remained a significant predictor of lower confidence levels, even upon adjusting for war experiences. These results indicate that regardless of their specific war experiences, female former CAAFAG may find it more difficult to maintain positive self-esteem and confidence in the post-conflict environment.

In measuring exposure to violence, this study sought to distinguish subtypes of war exposures and avoid applying equal weight to qualitatively different experiences. [31, 32] Several researchers have argued that not all war stressors are equally detrimental to a child’s wellbeing and that qualitative differences between stressors should be examined across different settings. [20, 32] Indeed, the present analysis indicated that different forms of violence exposure had different effects on the psychosocial adjustment of male and female CAAFAG. For example, killing/injuring others had negative effects on all mental health outcomes across genders, while death of a caregiver had specific implications for depression and anxiety. Qualitative data helps make these distinctions even clearer. An older male adolescent from Bo who participated in injuring others reported frequent feelings of aggression and hostility:

“If I am reported, at times I feel like fighting the teacher. Even at home if I do anything wrong and they correct me I feel hurt and become angry… At times I behave violently with my guardian …even though later I realize that I have behaved badly.”

A younger adolescent girl from Kono described difficulty in coping with loss of a parent:

“My mother was killed in front of my eyes…At times I will sit and think about all that and I feel lost and I cry.”

Experiences of rape were shown to be detrimental to all youth in the sample. However, male survivors of rape evidenced even higher levels of anxiety and hostility symptoms. These findings highlight that female and male CAAFAG require attention due to the psychological consequences of sexual violence. To our knowledge, only one quantitative study on former soldiers explores the mental health outcomes of male rape survivors: in Liberia, Johnson et al. [38] reported that approximately one-third of adult male ex-combatants in their sample had experienced sexual violence. Compared to men who did not report sexual abuse, these males suffered much higher rates of PTSD, social dysfunction and suicidal ideation; the same association was not true among female ex-combatants. [38]

In comparison to Johnson et al., only 5% of our male CAAFAG reported sexual abuse. However, it is likely that rape was under-reported by males, and that the associations uncovered by our study may thus be underestimated. Qualitative data revealed that females generally share experiences of rape with their mother or close friends; however, it is likely that males hide these experiences even from their closest family members and peers. Boy survivors of rape may suffer from hidden sources of stigma and shame, which could contribute to the heightened levels ofanxiety and hostility among male rape survivors in this sample. The issue of male rape in Sierra Leone has been largely ignored by community sensitization campaigns and services for survivors of gender-based violence. While future rehabilitation programming should continue to direct attention to the topic of sexual violence facing females, this study’s findings recommend that broader programmatic responses also consider male victims.

Some study results were unexpected. For instance, experiencing rape not only had expected associations with anxiety and hostility, but also had positive associations with prosocial behavior and confidence. These unexpected associations have been recorded in previous research. [39] One possible explanation is that youth may have developed resourcefulness and agency in response to harsh treatment. The population of children who survived the harshest treatment may show selection patterns giving preference to individuals with shrewd survival skills, self-efficacy, and confidence. In some cases, youth may also strive for positive social interactions in order to counteract community stigma. [19] The ability of these youth to exert their own sense of agency to overcome community provoking and ensure good relations that facilitate acceptance was also documented in our qualitative data:

“We know how to behave ourselves. We don’t do things that will make them brand us as bad. If we are called upon to assist we do so. If we see an old woman [tending] her farm we will go and help her.”

- (male, older adolescent)

In addition, the finding of increased vulnerability to depression and anxiety among males who lost a caregiver was also unexpected. One might anticipate that females in a patriarchical society like Sierra Leone would be more dependent on caregivers to help protect and support them in the post-conflict environment and thus made more vulnerable by their loss. However, in the case of male CAAFAG, loss of caregivers may have shifted family economic and social burdens to young men who returned at the end of the war which may have contributed to increased risk for depression and anxiety.

Finally, findings on positive indicators of psychosocial adjustment point to some promising sources of resilience in these youth. Attending school was associated with higher levels of prosocial attitudes and confidence, adjusting for all other factors. Qualitative data attests to the ways in which school access was a universally important goal for most youth in our study:

“Yes, [school] was very important and beneficial to me because with education I will be able to help my family..“

- (female, older adolescent)

For some girls, the stigma of having been a former child soldier may present additional barriers to school access. In some cases, this could mean lower investment from their families to ensure that they have school access:

“When I came and stayed with my cousin. She wasn’t willing to put me back in school because she said I had known the world [no more a virgin] and I have stayed with the rebels. She said it would be a waste of time and money.”

- (female, adolescent)

In order to address poor family relations and facilitate community acceptance, ICC outreach to families and the work of community sensitization programs are important. [19] In the present analysis, youth served by ICCs demonstrated higher levels of confidence and prosocial behavior. This relationship deserves further examination in future research.

A number of study limitations warrant mention. The ability to interpret the magnitude of mental health problems observed among former CAAFAG is limited by a lack of information on pre-war levels of mental health problems among youth in Sierra Leone and by a lack of normative samples of Sierra Leonean youth never associated with an armed group. Furthermore, although standard HSCL-25 clinical cut-points were applied to determine likely levels of clinical depression and anxiety, these thresholds must be treated with caution, as they have not been validated in this culture and setting. In addition, the small percentage of rape survivors included in the sample limited our statistical power to examine the moderating effect of gender on rape and psychosocial adjustment. In the future, larger samples would allow more robust examinations of these relationships. In addition, we only examined a specified set of mental health outcomes so we cannot generalize our findings to other conditions nor can we provide information on how the outcomes examined here are associated with impairments in functioning. Overall, the percent of variability explained by each of these predictors is moderate at best, indicating that other, unexamined variables are also at play. In particular, future studies should include further examination of post-conflict stressors and protective resources.

Conclusion

The present study contributes to a growing body of literature examining the experience of child soldiers by gender. In particular it provides quantitative data on rates of war experiences among male and female CAAFAG to shed light on important differences and similarities. This study emphasizes that children’s psychosocial adjustment must be considered in light of war experiences, post-conflict resources and gender.

Our findings have important programmatic and policy implications. They suggest that post-conflict resources should consider the unique adversities facing boys and girls, and in particular the hardships and lack of opportunity that many female CAAFAG face. [7, 40] In addition, our findings show that gender-based violence programs may overlook a small but very vulnerable population of male sexual abuse survivors. All CAAFAG who have lost caregivers face increase risk of depression and anxiety, but these effects may be more pronounced in boys who may have to shoulder additional family economic and social burdens.

The reintegration process for both male and female former child soldiers is complex. Fostering and rebuilding family and community relations may be critical to improving the long-term psychosocial adjustment of youth. Child-level interventions that provide immediate psychosocial support, proper follow-up, and opportunities for education and livelihoods are critically important. Additionally, family and community-level interventions should ensure that war-affected youth have the guidance and supports they need to set and achieve goals. All interventions should be designed to consider the influence of gender on profiles or risk and resilience. The authors hope that this and future research can raise awareness – both among local governments and in the international community – of the need to invest in reasonable, effective, and sustainable responses that support the mental health of all war-affected children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sidney Atwood for his assistance in data management and analysis.

This study was funded by the United States Institute of Peace, USAID/DCOF, Grant #1K01MH077246-01A2 from the National Institute of Mental Health, the International Rescue Committee and the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.UNICEF. Paris principles: Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed conflict. New York: UNICEF; 2007. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson J, Cripe L. Assessment of DCOF-Supported Child Demobilization and Reintegration Activities in Sierra Leone. US Agency for International Development; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kline PM, Mone E. Coping with War: Three Strategies Employed by Adolescent Citizens of Sierra Leone. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2003;20(5):321–333. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepler S. The Rites of the Child: Global Discourses of Youth and Reintegrating Child Soldiers in Sierra Leone. Journal of Human Rights. 2005;4:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medeiros E. Integrating Mental Health into Post-conflict Rehabilitation: The Case of Sierra Leonean and Liberian ‘Child Soldiers’. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(3):498504. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers. Child soldiers: Global report 2008. London: Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKay S, Robinson M, Gonsalves M, et al. Girls Formerly Associated with Fighting Forces and Their Children: Returned and Neglected. London: Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denov M. Girl soldiers and human rights: Lessons from Angola, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and Northern Uganda. International Journal of Human Rights. 2007;12(5):813–836. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKay S, Mazurana D. Where are the girls? Girls in fighting forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone, and Mozambique: Their lives during and after war. Montreal: International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKay S. Girls as “Weapons of Terror” in Northern Uganda and Sierra Leonean Rebel Fighting Forces. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 2005;28(5):385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turshen M, Twagiramariya C. What women do in wartime: gender and conflict in Africa. London; New York: Zed Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazurana DE, McKay SA, Carlson KC, et al. Girls in Fighting Forces and Groups: Their Recruitment, Participation, Demobilization, and Reintegration. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 2002;8(2):97–123. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denov MS. Wartime sexual violence: Assessing a human security response to war-affected girls in Sierra Leone. Security Dialogue 2006. 2006 Sep;37(3):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghlan B, Ngoy P, Mulumba F, et al. Mortality in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: An Ongoing Crisis. New York, NY: The International Rescue Committee; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stark L. Cleansing the wounds of war: An examination of traditional healing, psychosocial health and reintegration in Sierra Leone. Intervention: International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work & Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict. 2006;4(3):206–218. [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Bushra J. Fused in combat: gender relations and armed conflict. Development in Practice; Routledge: 2003. p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ. Nepali concepts of psychological trauma: the role of idioms of distress, ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology in alleviating suffering and preventing stigma. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;34(2):322–352. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brett R. Girl Soldiers: Denial of Rights and Responsibilities. Refugee Survey Quarterly. 2004;23(2):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE, et al. Past horrors, present struggles: the role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jan;70(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macksoud MS, Aber JL. The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child development. 1996 Feb;67(1):70–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen A, Sarigiani PA, Kennedy RE. Adolescent depression: Why more girls? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:247–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01537611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, et al. A second look at comorbidity in victims of trauma: The posttraumatic stress disorder-major depression connection. Society of Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:902–909. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMullin C, Loughry M. Investigating psychosocial adjustment of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone and Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2004;17(4):460–472. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annan J, Blattman C, Horton R. The state of youth and youth protection in northern. Uganda: UNICEF; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Tol WA, et al. Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. JAMA. 2008 Aug 13;300(6):691–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boothby N, Crawford J, Halperin J. Mozambique child solider life outcome study: Lessons learned in rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. Global Public Health. 2006;1(1):87–107. doi: 10.1080/17441690500324347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Schuyten G, et al. Post-traumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet. 2004 Mar 13;363(9412):861–863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayer CP, Klasen F, Adam H. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007 Aug 1;298(5):555–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Utas M, Persson M, Coulter C. Young female fighters in African wars: conflict and its consequences: The Nordic Africa Institute, Conflict, Displacement and Transformation. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breslau N. Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gend Specif Med. 2002 Jan-Feb;5(1):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netland M. Event-list construction and treatment of exposure data in research on political violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005 Oct;18(5):507–517. doi: 10.1002/jts.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Layne CM, Olsen JA, Baker A, et al. Unpacking trauma exposure risk factors and differential pathways of influence: Predicting post-war mental distress in Bosnian adolescents. Child development. 2010;81(4):1053–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974 Jan;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolton P, Neugebauer R, Ndogoni L. Prevalence of depression in rural Rwanda based on symptom and functional criteria. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002 Sep;190(9):631–637. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 37.SAS Institute Inc. SAS. 9.1.2. Cary, North Carolina: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson K, Asher J, Rosborough S, et al. Association of combatant status and sexual violence with health and mental health outcomes in postconflict Liberia. JAMA. 2008 Aug;300(6):676–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betancourt TS, Borisova II, Brennan RB, et al. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child development. 2010;81(4):1077–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wessells MG. Child soldiers: from violence to protection. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]