Abstract

Purpose

Adolescents are at high risk for HIV infection, yet have not been included in HIV vaccine trials.

Methods

In preparation for their enrollment in HIV vaccine trials, 100 HIV-negative 14 to 17 year olds from Cape Town were recruited into a cohort. HIV, syphilis, pregnancy testing, and sexual risk questionnaires were performed at varying intervals for one year.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 15 years, and 70% were female. Recruitment was completed in three months. Retention was 82% at 1 year. The main reasons for dropout were relocation to other communities, phlebotomy, and visit frequency. In a Cox proportional hazards model, only female gender was significantly associated with retention. No change in reported sexual risk occurred, but the proportion knowing their partners’ HIV status was significantly higher (17% at baseline, 83% at one year; p<0.001). There were five pregnancies during follow-up.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective adolescent HIV prevention cohort in Southern Africa. Despite reports of risky sex and high pregnancy rates, HIV seroconversions did not occur in the retained cohort. HIV prevention trials with high-risk adolescents will require rigorous efforts to prevent pregnancy, and may require risk eligibility criteria. Retention may improve with transport provision, incentivizing visits, and efforts to retain males.

Keywords: Adolescents, HIV, sexual risk, retention, cohort

Introduction

Although HIV prevalence rates around the world vary, it is clear that the age group of highest risk for HIV infection globally is youth [1]. Therefore, adolescents and preadolescents will be target populations for a preventative HIV vaccine. The development of a successful HIV vaccine is taking far longer than expected, and any additional delay in implementing phase I/II HIV vaccine trials in adolescents may result in excluding youth from efficacy trials. This would result in extended time to vaccine licensure for adolescents, with consequent ongoing preventable infections.

Although Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine trials enrolled adolescents from an early stage [2], no HIV vaccine trials have included participants under the age of 18 years, except for trials in neonates. Enrolment of adolescents in HIV vaccine trials is perceived as potentially challenging for a number of reasons. Firstly, the stigma attached to HIV is seemingly greater than that associated with HPV, which is often associated with cancer rather than a sexually transmitted infection [3]. Therefore, enrolling adolescents at high risk for HIV, where parental consent is required, is complicated. Second, HIV is a well-known STI, as opposed to HPV, and therefore the potential for sexual disinhibition as a result of perceived protection from vaccination exists within the trial. Although no evidence of sexual disinhibition has been reported in adult HIV prevention trials [4–6], there is the possibility that adolescents may have a greater tendency toward disinhibition than adults, due to their potential for greater risk-taking behaviour. Thirdly, adolescents are thought to be difficult to recruit and retain in longitudinal studies, although data from HPV vaccine and other cohort trials do not support this notion [7,8].

HIV vaccine trials require data on HIV incidence in the population under study in order to calculate sample size. There have been a few studies of incidence in South African youth. Hlabisa, in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal, has incidence data based on the standardized algorithm for recent HIV-1 seroconversion (STARHS) technique using ELISAs of differing sensitivities. Incidence of HIV-1 using this technique was 5.4% in 15 year olds in 1998 [9]. Prevalence in this age group is assumed to closely approximate annual incidence [1] and varies from 4% to 21% per year in sub Saharan African countries.

In preparation for the inclusion of adolescents in HIV vaccine trials, we recruited 14 to 17 year old adolescents from a peri-urban community into a one-year retention cohort, with regular HIV, pregnancy, and STI testing, as well as self-reported sexual risk and other behavioural and knowledge assessments.

Methods

The prospective cohort study was conducted between April 2006 and September 2007 in a peri-urban, Xhosa community near Cape Town. This community has an antenatal HIV prevalence of 29% [10], and a population of 15,000 people with one primary care clinic. Recruitment occurred through three methods, each identified by means of a flyer of a different color: direct recruitment through the community educators; recruitment from the clinic voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) service; and indirect recruitment through family members of patients in the antiretroviral clinic.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from a parent or guardian and the adolescents respectively. Eligibility criteria included: age between 14 and 17 years; HIV-negative at screening; and a negative urine pregnancy test for females.

Visits were three-monthly for one year. Participants completed paper questionnaires on demographics, sexual risk behaviour, HIV knowledge, and perceived risk for HIV. The questionnaires were available in both English and the local language, isiXhosa, and were interviewer-assisted; the study nurse read the questions out loud so as to ensure understanding, and the participant chose an answer out of sight of the interviewer to allow confidentiality. Paper methods have proven reliable for sexual risk behavior data collection from adolescents in this community previously [11]. The sexual risk survey instrument, completed at baseline and at 12 months, contained questions covering the following domains: demographics, sexually transmitted infection symptoms and treatment, sexual history (including partner history), condom use, transactional sex, and coerced sex. Additional items investigated knowledge of HIV and HIV vaccines, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials. Small group education sessions around HIV and HIV vaccines were held between month two and three, with pre and post education knowledge questionnaires. Most responses were multiple choice with space to provide additional information, and with the option to refuse to answer. All data collection was confidential. Participants received transport reimbursement and a snack for their attendance to study visits. Participants who withdrew were given a questionnaire regarding their reasons for doing so. Those who were lost-to-follow up were traced through home visits, and the withdrawal questionnaire was either completed by the participant or a family member if the participant was not available.

HIV and syphilis testing, and pregnancy testing where applicable, were performed at baseline and every three months thereafter. Rapid HIV testing was performed using Abbott Determine HIV 1/2, and positive results were confirmed using a second test (Efoora HIV Rapid Test HIV 1/2). Indeterminate results were confirmed via laboratory ELISA. Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) was performed to ascertain the participant’s syphilis status with reflex fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA) testing for positive or indeterminate results.

Data were entered into an Access database and analyzed using Stata Version 10.0 (College Station, Texas, USA). Bivariate analyses using chi-square, Fisher’s exact and t-tests were performed to examine the associations between participant demographic characteristics, sexual risk behaviors, pregnancy, and loss-to-follow up (LTFU). Cox proportional hazards models predicting LTFU, excluding those lost due to relocation, were calculated to examine associations after multiple statistical adjustments. Multiple logistic regression models were developed to identify variables predictive of pregnancy in the female participants. Variables were included in the models if they were hypothesized to have an effect on retention or pregnancy, and were removed from models if their removal did not affect associations involving other covariates. The results of these models are presented as hazards ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI’s). All statistical tests are 2-sided at α=0.05.

Results

Of the 107 adolescents screened for the study, all were recruited through direct outreach activities, and none from VCT or family members on treatment. Three participants were ineligible due to HIV infection, three due to pregnancy, and one was underage. The study was fully enrolled in four months.

The mean age of the cohort at enrolment was 15.0 (range 14.0–17.9) years, and 70% were female. The median highest level of education achieved was 8th grade (range, <6 to 11). All participants were attending school. Although 94% of adolescents were living with their mother, only 42% were living with people they considered both parents (there was no distinction made between non-biological and biological parents in the questionnaire).

Overall 43% of participants reported having ever had sex at baseline, 13 (30%) of whom reported having more than one partner in the past 12 months (Table 1). Of the sexually active adolescents, 95% considered their partners in the previous year to be a steady boyfriend or girlfriend, as opposed to a stranger, an acquaintance, a relative, or a school teacher. At baseline, two (2%) of all the adolescents reported having had anal sex in the past 6 months, and none reported having sex with someone on the first day they met, or having transactional sex (sex for money, drugs, a place to stay, transport, clothing, or, food). Of the sexually active adolescents, 24 (59%) reported consistent condom use in the past six months, yet only 7 (17%) of them knew the HIV status of their partners as negative.

Table 1.

Reported sexual behaviour of the cohort at baseline and at one year.

| Behaviour | Baseline | 12 months | P value* |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than 1 partner past year | 13 (13%) | 10/69 (14%) | 0.197 | 2.0 (0.62–7.46) |

| Ever had sex | 43 (43%) | 47/69 (68%) | <0.001 | 0.06 (<0.01–0.35) |

| Partner in the last year steady boy/girlfriend | 41/43 (95%) | 44/46 (96%) | 1.0 | 1 (0.1–78.5) |

| Anal sex past 6 months | 2/99 (2%) | 1/69 (1%) | 1.0 | 1 (0.1–78.5) |

| Casual sex past 6 months | 0/43 | 1/47 (2%) | n/a | |

| Money for sex past year | 0/43 | 1/47 (2%) | n/a | |

| Sex on alcohol or drugs past year | 5/43 (12%) | 2/47 (4%) | 1.0 | 1.0 (0.01–78.4) |

| Partner on drugs past year | 5/43 (12%) | 4/46 (9%) | 0.414 | 2 (0.29–22.1) |

| Partner forced sex past year | 2/43 (5%) | ** | ||

| You forced partner past year | 1/43 (2%) | ** | ||

| Always used condom past 6 mo | 24/41 (59%) | 33/47 (70%) | 0.796 | 0.88 (0.27–2.76) |

| Know partner HIV negative past | 7/42 | 40/48 (83.3%) | <0.001 | 0 (0–0.24) |

| year | (16.6%) |

McNemar’s paired t-test

Not asked at 12 month visit

There were few statistically significant changes in sexual behaviour between baseline and the final visit (12 months) although more adolescents had become sexually active (43%, vs. 68%; p<0.001) over the study period (Table 1). There was, however, a large increase in the proportion of adolescents who knew their partners HIV status as negative (17% vs. 83% by the end of the study; p<0.001).

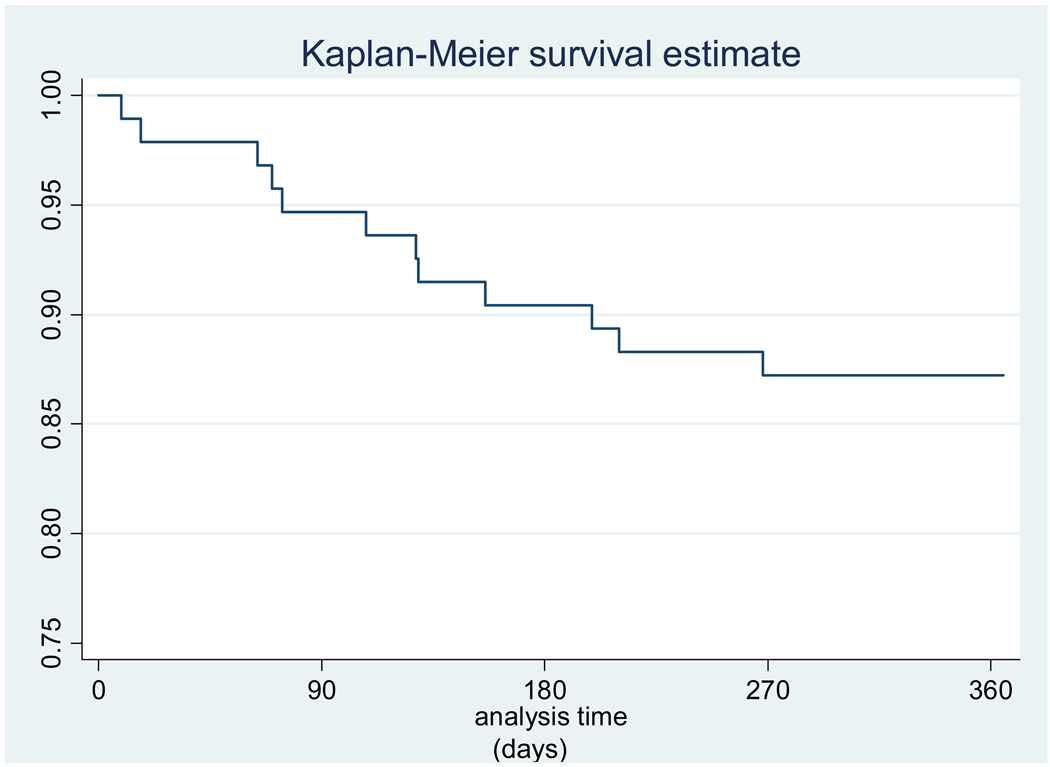

Retention was 82% at one year, and most of the attrition occurred before the third visit (n=13, 81% of all LTFU). Relocation to other communities accounted for 7 (35%) of the participants LTFU (Table 2). Once relocation to other nearby communities was excluded, retention was 87% (Figure 1). The most common reported reasons for withdrawal were the frequency of phlebotomy and of clinic visits (Table 2). Although pregnant females were offered continued follow-up, two chose to withdraw after the diagnosis of pregnancy. In a Cox proportional hazard model that excluded adolescents who had relocated and included age, gender, sexual activity, perceived HIV risk, and an intact family unit, loss-to-follow-up was associated with male gender (HR 7.24; 95% CI 1.40–37.44) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Reasons for loss-to-follow-up (n=18). Participants could choose more than 1 option.

| Reason for withdrawal of loss to follow-up | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Relocated to another community | 6 (33) |

| Frequency of blood draws | 10 (56) |

| Frequency of clinic visits | 7 (39) |

| Personal questions in the questionnaire | 2 (11) |

| Pregnancy | 2 (11) |

| Hospitalised (unknown cause) | 1 (6) |

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier curve of retention over one year (excluding loss due to relocation).

Table 3.

Predictors of loss-to-follow-up excluding relocation

| Factor (at baseline or visit 2) |

Lost to follow up (n=12) |

Retained (n=82) |

Univariate | Multivariate model* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Age (years) | 14.9 | 14.9 | 0.99 | 0.52– 1.88 | 0.86 | 0.40– 1.88 |

| Male gender | 50 % | 27 % | 2.56 | 0.82–7.92 | 7.24 | 1.40– 37.44 |

| Had sex ever | 50 % | 50 % | 1.43 | 0.46–4.42 | 4.04 | 0.74– 22.03 |

| Perceived at risk for HIV | 25 % | 16 % | 0.77 | 0.29–2.07 | 0.70 | 0.23– 2.08 |

| Live with both parents | 25 % | 44 % | 0.44 | 0.12–1.61 | 0.29 | 0.07– 1.20 |

Adjusted for all other variables in table

HR: Hazard Ratio; CI: Confidence interval

Of the retained cohort, there were no HIV seroconversions and no positive syphilis tests in the 12 month follow-up period. However, there were five pregnancies amongst the female participants (7%); two 14 year olds, and three 15 year olds. In a multivariate analysis predicting pregnancy which included age, education level, perceived risk for HIV, and living with their mother, the odds for pregnancy was significantly lower in adolescents with maternal figures in the household (OR 0.03; 95% CI <0.01–0.83). No such association was evident with paternal households. There were no pregnancies in households with both parents present.

Discussion

The presence of high-risk behavior in this young age group confirms that early adolescence is a critical time point for HIV prevention interventions. In addition to reports of risky sexual behavior in this cohort, there was also a high pregnancy rate, confirming that unprotected sex was occurring. However, there was not a single HIV seroconversion or positive RPR during the year. In a randomly-selected, cross-sectional study performed in the same community during 2004 – 2005, we found an HIV prevalence of 6.6% amongst 14 year olds, jumping to 17.9% amongst 18 year olds [12]. Possible explanations for the lack of seroconversions in our current study are that volunteers recruited via word-of-mouth and community outreach may have led to enrolment of a group with particularly low HIV risk or partner prevalence. Since the group was small, the lack of HIV infections may have happened by chance alone. Another possibility is that participants who were lost-to-follow-up may have been a higher risk group for incidence infections, although there was no association with reported sexual activity or perceived HIV risk and retention identified in the model of this small sample.

Other possible explanations for the lack of HIV seroconversions is the provision of accessible HIV testing resulting in serosorting, defined as the practice of identifying social and sexual partners based on HIV status. This explanation may be supported by the significant change in the proportion of adolescents who knew the HIV status of their partners by the end of the study. In a study of a behavioural intervention to reduce HIV transmission in men who have sex with men, Morin et al [13] found reduced transmission risk acts in both the intervention and the control group, that was due to serosorting. It is possible that study participation and the frequency of HIV testing in our study encouraged adolescents to choose less risky partners. In addition, VCT has been effective in reducing risk in other populations [14]. One of the frequently cited protests against the inclusion of adolescents in HIV prevention research is the theoretical risk of sexual disinhibition [15], although no evidence of sexual disinhibition has been found in previous HIV vaccine trials with adults [6]. Certainly, we found no evidence of sexual disinhibition over the period of the study, albeit that no biological interventional product was given, in this adolescent cohort. If anything, participation in HIV prevention research may have reduced risk for these adolescent participants.

Recruitment of the cohort was rapid and was best achieved by community outreach activities. It is possible that the other recruitment routes, i.e. VCT and patients in HIV care, underperformed due to poor engagement of the counselors and clinicians involved in these services. Community outreach, together with a lack of stated high-risk behavioural criteria, may have been associated with the recruitment of a cohort at low risk for HIV acquisition, however, and therefore future trials that may require a higher risk population may need to explore other avenues of recruitment, such as sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics. VCT is underutilized by adolescents in this and similar communities in Southern Africa [16,17], and therefore at present is not a useful venue for recruitment of high-risk adolescents. Adolescent-friendly VCT should be a high priority in settings such as these. Finally, a certain level of behavioural risk may need to become part of the inclusion or exclusion criteria

Retention of the cohort was 82% at one year. Adolescents cited frequent blood draws and clinic visits as the major deterrent for retention. It is unlikely that HIV vaccine trials will have fewer clinic visits or blood draws than the three-monthly visits in our study. The majority of the dropout was between the first and third visits, thereafter adolescents were more likely to be retained. Therefore adolescent retention in HIV prevention research may be improved by requiring a number of visits prior to enrolment to allow for the early attrition. Female gender was significantly associated with retention, therefore male-targeted retention efforts will be necessary. Relocation to other communities was also a common cause of dropout, and transport could be provided to overcome this. Finally, the pregnancy rate in these teens is unacceptably high for an HIV vaccine trial, and LTFU would have been greater if pregnancy was a reason for study withdrawal, as is the case for HIV vaccine trials. Vaccine trial sites may need to provide on-site family planning and counseling. The association between fewer pregnancies in households where mothers are present is intriguing and should be examined further, but enrolling adolescent females based on family structure to avoid pregnancies would be logistically difficult.

These results should be interpreted carefully for several reasons. Our relatively small sample size means that the estimate of events is somewhat imprecise. Response biases in the collection of reported high-risk sexual behaviors always exist in studies of self-reported behaviors, especially when questionnaires are interviewer-administered. Optimal methods for collecting sensitive information from this age-group should be explored. Finally, questions regarding HIV vaccine trial participation should be considered with caution in a study where no actual intervention is being explored.

The data presented here may facilitate the recruitment and retention of large numbers of adolescents in HIV vaccine trials. Trials similar to the one described in this paper but with an actual intervention such as a licensed vaccine could provide further insight into the challenges of HIV vaccine trials involving adolescents. Although there are challenges specific to the inclusion of adolescents in HIV vaccine trials, these must be overcome to ensure the rapid assessment of safety and efficacy of promising vaccine candidates in this important target group.

Acknowledgments

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C). This study was sponsored in part by the South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative. HBJ is supported in part by NIH Training grant 5T32HD007233-28.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors dedicate this paper to the late Professor Alan J Flisher whose contribution to the field of adolescent health in South Africa is unsurpassed.

References

- 1.WHO/UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update 2007

- 2.Rambout L, Hopkins L, Hutton B, Fergusson D. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomavirus infection and disease in women: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2007;177(5):469–479. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Read DS, Joseph MA, Polishchuk V, Suss AL. Attitudes and perceptions of the HPV vaccine in Caribbean and African-American adolescent girls and their parents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010 Aug;23(4):242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, Akumatey B, Clarke PL, Macqueen KM, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior among participants in a PrEP HIV Prevention trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 Dec;35(12):1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agot KE, Kiarie JN, Nguyen HQ, Odhiambo JO, Onyango TM, Weiss NS. Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo Districts, Kenya: prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):66–70. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242455.05274.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartholow BN, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Goli V, Koblin B, Para M, et al. HIV sexual risk behavior over 36 months of follow-up in the world's first HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 May 1;39(1):90–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143600.41363.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanford PD, Monte DA, Briggs FM, et al. Recruitment and Retention of Adolescent Participants in HIV Research: Findings From the REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) Project. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:192–203. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Nov 13–19;364(9447):1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouws E, Williams BG, Sheppard HW, Enge B, Karim SA. High incidence of HIV-1 in South Africa using a standardized algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Apr 15;29(5):531–535. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. Pretoria: DOH; National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Sero-prevalence Survey in South Africa 2007. 2008

- 11.Jaspan HB, Flisher AJ, Myer L, Mathews C, Seebregts C, Berwick JR, et al. Brief report: methods for collecting sexual behaviour information from South African adolescents--a comparison of paper versus personal digital assistant questionnaires. J Adolesc. 2007;30(2):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaspan HB, Berwick JR, Meyer L, et al. Adolescent HIV prevalence, sexual risk, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials. J Adol Health. 2006;39:642–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morin SF, Shade SB, Steward WT, Carrico AW, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. A Behavioral Intervention Reduces HIV Transmission Risk by Promoting Sustained Serosorting Practices Among HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Nov 4; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merson MH, Dayton JM, O-Reilly K. Effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions in developing countries. AIDS. 200;14 Suppl 2:S68–S84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swartz L, Kagee A, Kafaar Z, Smit J, Bhana A, Gray G, et al. Social and behavioral aspects of child and adolescent participation in HIV vaccine trials. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic Ill) 2005 Dec;4(4):89–92. doi: 10.1177/1545109705285033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD. The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: do families and friends matter? AIDS Care. 2008 Jan;20(1):101–105. doi: 10.1080/09540120701427498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H. "You must do the test to know your status": attitudes to HIV voluntary counseling and testing for adolescents among South African youth and parents. Health Educ Behav. 2008 Feb;35(1):87–104. doi: 10.1177/1090198106286442. Epub 2006 Jul 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]