Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to examine the interrelationships among individualism, collectivism, homosexuality-related stigma, social support, and condom use among Chinese homosexual men.

Methods

A cross-sectional study using the respondent-driven sampling approach was conducted among 351 participants in Shenzhen, China. Path analytic modeling was used to analyze the interrelationships.

Results

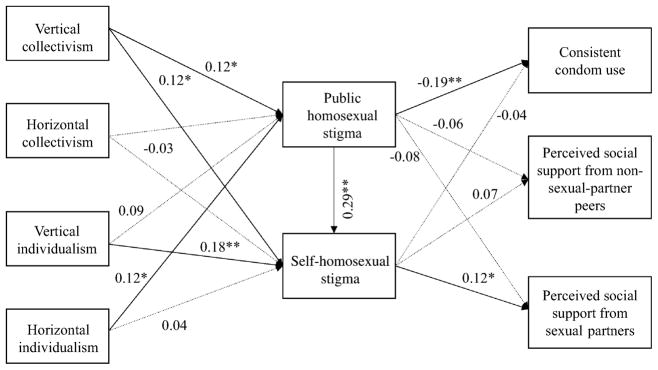

The results of path analytic modeling document the following statistically significant associations with regard to homosexuality: (1) higher levels of vertical collectivism were associated with higher levels of public stigma [β (standardized coefficient) = 0.12] and self stigma (β = 0.12); (2) higher levels of vertical individualism were associated with higher levels self stigma (β = 0.18); (3) higher levels of horizontal individualism were associated with higher levels of public stigma (β = 0.12); (4) higher levels of self stigma were associated with higher levels of social support from sexual partners (β = 0.12); and (5) lower levels of public stigma were associated with consistent condom use (β = −0.19).

Conclusions

The findings enhance our understanding of how individualist and collectivist cultures influence the development of homosexuality-related stigma, which in turn may affect individuals’ decisions to engage in HIV-protective practices and seek social support. Accordingly, the development of HIV interventions for homosexual men in China should take the characteristics of Chinese culture into consideration.

Keywords: collectivism, HIV/AIDS, homosexuality, individualism

Introduction

Homosexual men in China are facing two intertwined threats: homosexuality-related stigma and HIV infection. Since a significant proportion of homosexual men engage in HIV-risk behaviors, the HIV epidemic has been spreading in this stigmatized population in China (Wang et al., 2009). As in some other countries, homosexuality is largely unacceptable in Chinese society, homosexual men are thus widely stigmatized (Liu & Choi, 2006; Liu, Liu, Cai, Rhodes & Hong, 2009a).

Stigma has been defined as a discrediting attribute that decreases the status of an individual who possesses a characteristic that is undesirable in the eyes of society (Goffman, 1963). Conceptually, there are three forms of stigma: structural stigma, public stigma and self stigma. Structural stigma refers to the policies of private and public institutions or organizations that restrict the opportunities of stigmatized groups, and is created by socio-political forces (Corrigan et al., 2005). Public stigma refers to the general public’s negative attitudes, beliefs or reactions towards people with stigmatized attributes, such as homosexuality (Corrigan, 2004). This type of stigma can be perceived or experienced by homosexual men. However, self stigma or internalized stigma, refers to the fear, perceived by people who have such stigmatizing attributes, of societal attitudes and potential discrimination (Scambler, 1998). In a society that widely endorses stigmatizing attitudes, homosexual men may internalize these attitudes and believe that they should be stigmatized or discriminated against. Research has demonstrated homosexuality-related stigma and its consequences in populations of homosexual men (Diaz, Ayala & Bein, 2004; Neillands, Steward & Choi, 2008). Stigma is a complicated issue which is believed to be deeply rooted in culture (Valdiserri, 2002). Different forms of stigma have been identified in countries with different cultures (Murthy, 2002). Therefore, it is necessary to take the specific local culture into consideration when investigating the formulation and consequences of stigma.

Culture has been defined as a unique meaning and information system, shared by a group and transmitted across generations, that allows the group to meet basic needs of survival, pursue happiness and well-being, and derive meaning from life (Matsumoto & Juang, 2008). It has further been categorized into two main dimensions: collectivism and individualism (Triandis, 1995). Individuals in a collectivist culture tend to see themselves as interdependent within their groups and usually behave according to collectivist social norms. People in a collectivist society are advised to exercise emotional restraint in order to avoid shame and save face (Yang & Kleinman, 2008). In contrast, individuals in an individualist culture see themselves as independent of groups and generally behave according to personal choices. Individualistic people are motivated by their self-interests, which are often valued over the interests of their in-groups (Triandis, 1995). Both individualist and collectivist orientations coexist within individuals and cultures. For example, based on their studies, Ho and Chiu concluded that, although Chinese culture is more collectivist than individualist, both individualist and collectivist values are endorsed within Chinese culture (Ho & Chiu, 1994).

To measure cultural orientations at the individual level, Triandis proposed two sub-dimensions of individualism and collectivism (Triandis, 2001). In the vertical dimension, societies are hierarchically structured; members tend to accept inequality and acknowledge the importance of social status. In the horizontal dimension, societies are egalitarian in structure; members accept interdependence and equal status for all. Triandis proposed four types of cultures from these sub-dimensions (Triandis, 2001). Horizontal individualism is where people want to be unique and do their own thing. Vertical individualism is where people want to do their own thing and also to be the best. Horizontal collectivism is where people merge themselves with their in-groups. Vertical collectivism is where people submit to the authorities of the in-group and are willing to sacrifice themselves for their in-group. Although the consequences of individualism and collectivism have been conceptualized, few empirical studies have examined these consequences, including their consequences for homosexuality-related stigma.

Influenced by a collectivist culture, Chinese people tend to subordinate personal interests to those of the group or collective (Hui & Triandis, 1986). Individuals who are considered non-conforming to group values are devalued by a collectivist society. In China, homosexuality is not considered to be conforming to a group value (Lin & Lin, 1981). Therefore Chinese culture may foster homosexuality-related stigma. According to Confucianism, individuals are defined within the context of their familial relationships (Neillands et al., 2008). The cultural imperative of familial responsibility, rather than individual rights, results in the stigmatization of not only homosexual individuals, but also their family members (Lin, 1981). Many Chinese homosexual men are married to women while continuing to have secret homosexual relationships (Neillands et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2009). No studies have examined the relationships between the specific dimensions of Chinese culture and homosexuality-related stigma. Based on the above literature review, we hypothesized that high levels of collectivism would be positively associated with HIV-related stigma and homosexuality-related stigma, while high levels of individualism would be negatively associated with these two types of stigma.

HIV- and homosexuality-related stigma can affect social support and HIV prevention practices. A recent meta-analysis of 21 studies reported that HIV stigma was negatively associated with social support (Smith, Rossetto & Peterson, 2008). Studies also found that individuals who were socially stigmatized tended to seek support from people with similar conditions. For example, people living with HIV/AIDS were more likely to seek support from others living with HIV/AIDS (Davison, Pennebaker & Dickerson, 2000). Similarly, while gay men who were psychologically distressed were less likely to seek social support, a higher acceptance of gay identity at the community level led to a higher level of seeking for social support (Turner, Hays & Coates, 1993). Moreover, research has revealed that high levels of stigma are associated with inconsistent condom use and are also associated with increased likelihood of engagement in sexual-risk behaviors for HIV among homosexual men (Preston et al., 2004; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz & Sanchez, 2009). Based on these empirical studies, we further hypothesized that higher levels of HIV- and homosexuality-related stigma experienced by homosexual men were associated with inconsistent condom use, higher levels of social support from sexual partners, and lower levels of social support from non-sexual-relation peers. The hypothesized interrelationships among individualist and collectivist cultures, HIV- and homosexuality-related stigma, social support and condom use are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model.

Methods

Study Site and Subjects

The study site has been previously described (Liu et al., 2009a). A cross-sectional study was conducted among homosexual men in Shenzhen City, China. Shenzhen, the first special economic region in China, is located along the southern coast of China, bordering Hong Kong and Guangzhou. An estimated 60,000 homosexual men live in the city (Feng et al., 2005). A man was eligible for this study if he: (1) was between 18 and 45 years old; (2) reported having engaged in anal intercourse with one or more men in the past year; and (3) had lived in Shenzhen for more than 3 months at the time of the interview.

Respondent-driven Sampling (RDS)

The respondent-driven sampling approach was used to recruit homosexual men (Heckathorn, 1997). We selected 12 homosexual men who served as ‘seeds’. The seeds received an explanation of the study’s purpose and three coupons to recruit other homosexual men from their network. All new recruits in the subsequent waves received an anonymous interview and three coupons. The respondent-driven sampling approach generated a sample that covered a broad cross-section of the target population, indicating acceptable representativeness (Liu et al., 2009a). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Virginia Commonwealth University and Chinese Center for HIV/STD Control and Prevention.

Interview

Eligible subjects participated in a face-to-face anonymous interview in a private room. All interviewers received intensive training in interviewing techniques, developing rapport, and ensuring confidentiality before conducting the interviews. A pilot test of the interviewers’ skills, questionnaires, and respondent-driven sampling procedures were performed with 10 homosexual men in order to ensure suitability of language and context.

Measurements

Stigma

The psychometric assessment of HIV stigma, public homosexual stigma, and self-homosexual stigma among this homosexual men sample of has been reported (Liu, Feng, Rhodes & Liu, 2009b). Public HIV stigma was measured with seven items (e.g., HIV infected people would lose their friends if they knew their HIV status). Public homosexual stigma was measured with 10 items (e.g., Many people would treat a gay individual differently than they would treat others). Self-homosexual stigma was measured with eight items (e.g., I am afraid that my family and friends would find out about my sexual orientation). Higher scores on these measurement scales indicated a greater perception of HIV and homosexual stigma. The Cronbach coefficient alpha was 0.81 for HIV stigma, 0.85 for public homosexual stigma, and 0.78 for self-homosexual stigma. All measures are available from the authors on request.

Individualism and collectivism

Individualism and collectivism were measured in a scale adapted from the scales developed by Triandis (Triandis, 1995) and Chirkov et al. (Chirkov, Ryan, Kim & Kaplan, 2003). Horizontal individualism was measured with eight items (e.g., I would like to do what I like. I do not care about what others think). Vertical individualism was measured with seven items (e.g., I will try my best to do things well. I do not like to fall behind others). Vertical collectivism was measured with six items (e.g., I could give up a personal pursuit or interest in order to take care of my family). Horizontal collectivism was measured with five items (e.g., I will try my best to maintain harmony in a community or a group). Respondents were asked to rate the extent of their agreement to these items across a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score for each dimension was calculated by summing all item scores. The Cronbach coefficient alpha was 0.66 for vertical individualism, 0.57 for horizontal individualism, 0.51 for vertical collectivism, and 0.60 for horizontal collectivism.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was measured in an inventory modified from the Norbeck Social Support questionnaire (NSSQ) (Norbeck, Lindsey & Carrieri, 1983; Liu, et al., 2009c). Six items were used to measure social support that homosexual men perceived to receive from sexual partners and non-sexual-partner peers (such as family members, teachers, classmates, colleagues, villagers and others). Respondents rated the possibility of perceived social support from 0 (not possible at all) to 4 (quite sure). Example items are take care of the respondent if he was confined to bed for 2–3 weeks; agree with or support the respondent’s actions or thoughts; or make the respondent confide in the network members. The total score for each perceived social support source was calculated by summing all individual item scores. Reliability measured by Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was 0.75 for non-sexual-partner peers’ support and 0.70 for sexual partners’ support.

Consistent condom use

Participants were asked about the frequency of condom use in the past six months. The frequency was dichotomized as using condoms for every sexual act (consistent condom use) and not using condoms for every sexual act (inconsistent condom use).

Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients were estimated to describe the degrees of associations among variables of interest. Path analytic modeling was performed to test the hypothesized interrelationships presented in Fig. 1. Standardized coefficients (β) for all paths were estimated. The goodness-of-fit of models was assessed by a non-significant χ2 value, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.90, and comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Bryan, Schmiege & Broaddus, 2007). These analyses were completed using Mplus 4 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

A total of 351 homosexual men were recruited and interviewed. Sixteen subjects did not provide data on condom use and were excluded from the analysis, making a final sample of 335 homosexual men. The mean age of respondents was 27 years [ranging from 18 to 44 years old, standard deviation = 6.3]. Sixty-five percent of homosexual men had a high school education or higher. Thirty-eight percent worked in entertainment venues, such as bars, bathhouses, karaoke bars, and dancing halls, while 61% reported other types of work such as construction, factory, business, and self-employment. The majority of the respondents were single (78%). Sixty-one percent reported having used condoms for every sex act in the past six months.

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations and correlations for variables that were used in the path analytic model. Some correlations were statistically significant, e.g., higher levels of vertical collectivism were significantly correlated with higher levels of public HIV stigma, higher levels of public homosexual stigma, higher levels of self-homosexual stigma, higher levels of horizontal collectivism, and higher levels of vertical individualism. Although these correlations were significant, the correlation coefficients ranged from small to moderate in size, and this may suggest that the original hypothesized path model may be a poor fit for the data.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Culture, Stigma, and Social Support (n = 335)

| Variables | Correlation

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 1. Vertical collectivism | 2.04 | 0.56 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.11* | 0.15* | 0.15* | 0.05 | 0.16* | 0.24** | – |

| 2. Horizontal collectivism | 2.51 | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.27** | – | |

| 3. Vertical individualism | 2.27 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.17** | 0.17* | 0.33** | – | ||

| 4. Horizontal individualism | 2.00 | 0.53 | 0.15 | 0.14** | 0.14* | 0.09 | 0.15* | – | |||

| 5. Public homosexual stigma | 2.50 | 0.35 | 0.11* | −0.02 | 0.44** | 0.32** | – | ||||

| 6. Self homosexual stigma | 2.66 | 0.35 | 0.15** | −0.05 | 0.18** | – | |||||

| 7. HIV stigma | 2.16 | 0.36 | 0.02 | −0.03 | – | ||||||

| 8. Perceived social support from non-sexual-partner peers | 11.17 | 6.56 | −0.21** | – | |||||||

| 9. Perceived social support from sexual partners | 8.55 | 9.03 | – | ||||||||

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Path Analytic Model Analysis

Based on the relationship paths presented in the hypothesized model (Fig. 1), a standardized coefficient was estimated for each of the paths. The assessment of goodness-of-fit documented that this model did not fit data well (χ2 = 24.0, df= 20, p = 0.01, n=335). The value of RMSEA, TLI and CFI was 0.06, 0.89, and 0.73, respectively, indicating that the fit between model and data needed to be improved.

Due to the highly significant correlation between public homosexual stigma and public HIV stigma (r = 0.44, p < 0.01), we modified the model by removing all paths connected to public HIV stigma. In addition, we attempted to add two paths from perceived social support either from sexual partners or non-sexual-partner peers to condom use. However, the coefficients on the two paths (from the two types of perceived social support to condom use) were very low (β = 0.02, p > 0.05, and β = −0.1, p > 0.05) and the overall model fit was not acceptable. The revised model (the final model in Fig. 2) fit the data well. It had a non-significant model chi-square value (χ2= 8.3, df = 9, p = 0.59, n=335), and better values on the TLI (0.91), CFI (0.95), and RMSEA (0.045). The following relationships were found to be statistically significant in the revised model: (1) higher levels of vertical collectivism were significantly associated with higher levels of public homosexual stigma [β (standardized coefficient) = 0.12; that is, each 1 stantard deviation increase in vertical collectivism results a 0.12 standard deviation increase in public homosexual stigma score) and higher levels of self homosexual stigma (β = 0.12); (2) higher levels of vertical individualism were significantly associated with higher levels of self-homosexual stigma (β = 0.18); (3) higher levels of horizontal individualism were significantly associated with higher levels of public homosexual stigma (β = 0.12); (4) lower levels of public homosexual stigma were significantly associated with consistent condom use (β = −0.19; that is, the correlation between the residuals of public homosexual stigma and condom use was −0.19); (5) higher levels of self homosexual stigma were significantly associated with higher levels of social support from sexual partners (β = 0.12); and (6) higher levels of public homosexual stigma were significantly associated with higher levels of self-homosexual stigma (β = 0.29).

Fig. 2.

Standardized coefficients for paths in the final path model [(χ2 = 8.3, df=9, p=0.59, n=335); TLI = 0.91; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.045]. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

This study provides support for the expectation that collectivism and individualism may affect public and self-homosexual stigma, which, in turn, may influence decisions made by homosexual men to engage in HIV prevention practices and to seek social support. Although the interrelationships among cultural factors, stigma, social support, and protected sex are complicated, understanding them may facilitate the development of effective HIV prevention interventions for homosexual men. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study of its kind to look at these interrelationships among homosexual men.

This study supports the previous documentation of the co-existence of both individualist and collectivist orientations in Chinese culture. Findings revealed that Chinese homosexual men with a higher level of vertical collectivism appear to experience greater levels of both public and self-homosexual stigma. Vertical collectivism-oriented individuals usually submit to the authorities of the in-group and are willing to sacrifice themselves for their network peers (Triandis, 2001). Because homosexuality is not accepted by Chinese society, and is strongly disapproved of by authority figures (such as elders, team leaders, or parents), homosexual men may pay special attention to their authority figures’ feelings and reactions to their homosexuality. Consequently, they may perceive a higher degree of stigma. In addition, deeply influenced by Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, Chinese culture emphasizes not only egalitarianism but also team responsibility and sacrifice (Triandis, 1995). The rejection of homosexuality by their society may make homosexual men feel that they lose their dignity or face, and damage group values. One unexpected finding is that the level of horizontal collectivism is not associated with homosexuality-related stigma. Horizontal collectivism-oriented individuals tend to merge themselves with their in-groups. They may not perceive a high degree of stigma if the in-group peers are also homosexual men. However, additional research, especially using a qualitative approach, is needed to explain why there is no such association.

This study documented that vertical individualism was positively associated with self-homosexual stigma while horizontal individualism was positively associated with public homosexual stigma. This finding appears to contradict characteristics of individualism, as individuals with such orientation often disassociate with others’ concerns, place self-interest above those of the group, and do their own things regardless of group disciplines (Ho & Chiu, 1994). Presumably, homosexual men with high levels of individualism would not care about stigma attached to their homosexuality. One possible explanation for our findings is that individualism-oriented homosexual men may perceive that their desire for uniqueness or their passion for self-accomplishment is challenged by the larger collectivist community where homosexual behavior is not accepted and homosexuality-related stigma is highly displayed. They may feel marginalized because both individualism and homosexuality are not in harmony with their social or cultural environment where collectivism prevails. The marginalization of homosexual individuals may provoke stigma among homosexual men because their uniqueness and the best status are neither valued nor accepted by their community and, consequently, by themselves.

While HIV-related stigma was not associated with consistent condom use, public homosexual stigma was inversely related to condom use. When HIV-related stigma was removed from the model, public homosexual stigma remained inversely associated with consistent condom use (Fig. 2). HIV-related stigma may not be a major concern to homosexual men because they know that the majority of their peers are not infected with HIV. The main reason that people stigmatize and discriminate against HIV-infected individuals is that they do not accept their behavior or the practices through which individuals are infected (i.e., through sex or drug injection). Homosexual men may perceive that the public’s stigmatizing attitudes towards their identity of homosexuality is more important and substantial than HIV stigma.

In a society that ostracizes homosexuals, these men may choose practices that are less likely to lead to disclosure of their sexual identity. Due to the fear of disclosure of their homosexuality and the consequent discrimination, homosexual men may not participate in HIV intervention programs, thus limiting their exposure to prevention messages. Liu and Choi (2006) reported that, in order to avoid the disclosure of their sexual identity, homosexual men may not engage in safer sex, or refuse to accept health outreach services even when these services were are free. Our finding suggests that HIV intervention programs targeting homosexual men should include prevention or reduction of homosexuality-related stigma. For example, education programs targeted towards community members about homosexuality and the need for tolerance, such as has been done in HIV-related stigma programs, may be particularly helpful. Decreasing public homosexual stigma may also help decrease self homosexual stigma due to a reduction in discriminating attitudes from community members.

Homosexual men who have a high degree of self-homosexual stigma perceived more social support from their sexual partners, but not from non-sexual-partner peers. It is possible that homosexual men do not want to receive social support from non-sexual-partner peers because they may be concerned about rejection, especially in a collectivist society where homosexuality is disapproved of and stigmatized (Liu et al., 2006). A previous study among homosexual men in China also found that they continue to fear being rejected by their families or losing their job if they disclose their sexual preference (Choi, Diehl, Yaqi, Qu & Mandel, 2002). However, they may seek social support from their sexual partners because their sexual partners may share the same sexual issues and concerns, can be trusted, and will help them without stigmatizing them. This finding is consistent with findings of a study reporting that those who are socially stigmatized tend to seek support from people with similar conditions (Davison et al., 2000). Our findings imply that the formulation of peer support groups in homosexual mens’ sexual networks may provide them with comfortable venues where they can discuss solutions to cope with homosexual stigma and receive social support. These peer support groups can also be an avenue for the introduction of messages about the importance of condom use in all sexual encounters using the popular opinion leader strategy whereby key opinion leaders in certain populations are identified, trained and enlisted to help educate others in their group (Kelly, 2004).

There are several limitations that should be noted in our study. First, the study subjects were recruited from Shenzhen city which is not representative of all cities in China. Therefore, generalization of the findings to other populations of homosexual men should be made with caution. Since our study employed a cross-sectional design, findings should not be interpreted beyond associations. Reverse relationships may occur in cross-sectional studies; however, this may not be an issue in this study due to the nature of the variables being analyzed (e.g., stigma cannot cause or create culture, and condom use in a sexual encounter cannot create public homosexual stigma). Although Cronbach’s alphas were low for the four cultural constructs, factor analysis of the dimensionality indicated that there were four distinct sub-dimensions reflecting four subscales of collectivism and individualism. According to Cronbach’s (1990) argument of bandwidth and fidelity, if a measurement scale is designed to measure complicated and multifaceted phenomena (such as individualism and collectivism), and it includes a wide range of constructs for the enhancement of its measurement validity, then its internal consistency is usually compromised. As argued by Cronbach & Gleser (1965) and Singlis, Triandis, Bhawuk & Gelfand (1995) measurement scales with relatively low alphas do not necessarily mean that they are also low in validity. Previous studies have reported the reliability of horizontal individualism, vertical individualism, horizontal collectivism, and vertical collectivism scales measured by Cronbach’s alpha was from low to moderate (between 0.52 and 0.74) (Singlis et al., 1995; Lee & Choi, 2005). Nevertheless, future studies are needed to improve their reliability of the sub-scales.

Conclusion

These findings enhance our understanding of how stigma is influenced by individualism and collectivism, how it affects decisions to engage in HIV protective behaviors, and how it alters perceived social support among homosexual men. Given the potential influence of individualist and collectivist cultures on stigma and safer sex, the development of HIV interventions for homosexual men should take the specific characteristics of Chinese culture into consideration, and the prevention of homosexuality-related stigma should be an important component of HIV intervention programs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant (107010-41-RGAT) from the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). We are grateful to all participants for their generosity of time to provide the study data.

References

- Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov V, Ryan RM, Kim Y, Kaplan U. Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:97–110. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Diehl E, Yaqi G, Qu S, Mandel J. High HIV risk but inadequate prevention services for men on China who have sex with men: an ethnographic study. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:12. doi: 10.1023/A:1019895909291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. On the stigma of mental illness. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Heyrman M, Warpinski A, Gracia G, Slopen N, et al. Structural stigma in state legislation. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:557–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Essentials of psychological testing. 5. New York: HarperCollins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Gleser GC. Psychological tests and personnel decisions. Urbana, PL: University of Illinois Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Davison KP, Pennebaker JW, Dickerson SS. Who talks? The social psychology of illness support groups. The American Psychologist. 2000;55:205–217. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng T, Cai W, Tan J, Chen L, Shi X, Wang F, et al. Using capture-recapture method to estimate size of MSM in Shenzen. China: Haebin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:26. doi: 10.1525/sp.1997.44.2.03x0221m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y-FD, Chiu C-Y. Component idea of individualism, collectivism and social orginization. An application in the study of Chinese culture. In: Kim U, Triandis CH, Kagitcibasi C, Choi S-C, Yoon G, editors. Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication; 1994. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CH, Triandis HC. Individualism-collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology. 1986;17:24. doi: 10.1177/0022002186017002006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA. Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: resolving discrepant findings, and implications for the development of effective community programmes. AIDS Care. 2004;16:139–150. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001640986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W-N, Choi SM. The Role of Horizontal and Vertical Individualism and Collectivism in Online Consumers’ Response toward Persuasive Communication on the Web. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2005;11:article 15. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.tb00315.x. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/wnlee.html. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K-M. Traditional Chinese medical beliefs and their relevance for mental illness and psychiatry. In: Kleinman A, Lin T-Y, editors. Normal and abnormal behavior in Chinese culture. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company; 1981. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY, Lin MC. Love, denial and rejection: Responses of Chinese families to mental illness. In: Klienman A, Lin T-Y, editors. Normal and abnormal behavior in Chinese culture. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company; 1981. pp. 387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Liu JX, Choi K. Experiences of social discrimination among homosexual men in Shanghai, China. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:S25–S33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Liu H, Cai Y, Rhodes AG, Hong F. Money boys, HIV risks, and the associations between norms and safer sex: a respondent-driven sampling study in Shenzhen, China. AIDS and Behavior. 2009a;13:652–662. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Feng T, Rhodes AG, Liu H. Assessment of the Chinese version of HIV and homosexuality related stigma scales. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009b;85:65–69. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Feng T, Liu H, Feng H, Cai Y, Rhodes AG, et al. Egocentric networks of Chinese homosexual men: network components, condom use norms, and safer sex. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009c;23:885–893. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Yang H, Li X, Wang N, Liu H, Wang B, et al. Homosexual men and human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted disease control in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:68–76. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187266.29927.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, Juang L. Culture and Psychology. 4. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy RS. Stigma is universal but experiences are local. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neillands BT, Steward TW, Choi K-H. Assesment of stigma towards homosexuality in China: A study of homosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:838–844. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck JS, Lindsey AM, Carrieri VL. Further development of the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire: normative data and validity testing. Nursing Research. 1983;32:4–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston DB, D’Augelli AR, Kassab CD, Cain RE, Schulze FW, Starks MT. The influence of stigma on the sexual risk behavior of rural homosexual men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:291–303. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.291.40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G. Stigma and disease: changing paradigms. The Lancet. 1998;352:1054–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singlis TM, Triandis HC, Bhawuk D, Gelfand MJ. Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Research. 1995;29:36. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1266–1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(6):18. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Hays RB, Coates TJ. Determinants of social support among gay men: the context of AIDS. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:37–53. doi: 10.2307/2137303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdiserri RO. HIV/AIDS stigma: an impediment to public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:341–342. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang N, Wang L, Li D, Jia M, Gao X, et al. The 2007 Estimates for people at risk for and living with HIV in China: Progress and challenges. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;50:414–418. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong FY, Huang ZJ, Wang W, He N, Marzzurco J, Frangos S, et al. STIs and HIV among men having sex with men in China: a ticking time bomb? AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:430–446. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: the cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]