Abstract

Skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) is difficult to diagnose when a patient presents with multiple cranial nerve palsies but no obvious infectious focus. There is no report about SBO with septic pulmonary embolism. A 51-yr-old man presented to our hospital with headache, hoarseness, dysphagia, frequent choking, fever, cough, and sputum production. He was diagnosed of having masked mastoiditis complicated by SBO with multiple cranial nerve palsies, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, and septic pulmonary embolism. We successfully treated him with antibiotics and anticoagulants alone, with no surgical intervention. His neurologic deficits were completely recovered. Decrease of pulmonary nodules and thrombus in the sinus was evident on the follow-up imaging one month later. In selected cases of intracranial complications of SBO and septic pulmonary embolism, secondary to mastoiditis with early response to antibiotic therapy, conservative treatment may be considered and surgical intervention may be withheld.

Keywords: Mastoiditis, Skull Base Osteomyelitis, Thrombophlebitis, Septic Pulmonary Embolism

INTRODUCTION

Patients with atypical skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) are difficult to diagnose because multiple cranial nerve deficits mimicking symptoms caused by mass located at a posterior fossa often develop, even without definite abnormalities suspicious of ear problems (1). Mastoiditis can result in intracranial complications of SBO (2) and/or sigmoid sinus thrombosis (3). Most patients with mastoiditis require surgical debridement including mastoidectomy (4). Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis complicated by multiple pulmonary septic emboli was described by Hoshino et al. (5). Some children presenting with septic pulmonary emboli and deep venous thrombosis secondary to acute osteomyelitis of the long bones have been also reported (6). Here we describe the first, to the best of our knowledge, case of atypical SBO caused by masked mastoiditis complicated by sigmoid sinus thrombosis and multiple septic pulmonary emboli; the patient was successfully treated with antibiotics and anticoagulants. We suggest an alternative treatment option for successful non-surgical treatment of an immunocompetent patient who has intracranial complications of mastoiditis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 51-yr-old man presented to our emergency department with left temporo-occipital and retro-orbital facial pain of 1-week duration on April 3, 2009. There was no history of ear infection. At presentation, cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an encephalomalacic change in the right parietal lobe which was unrelated to the presenting manifestations; the patient was allowed to leave emergency department on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Three weeks later, the patient again presented to the emergency department with new-onset hoarseness, dysphagia, frequent choking upon swallowing liquids, fever, cough, and sputum production. The left temporo-occipital and retro-orbital facial pain had become aggravated and did not respond to conservative measures such as a soft diet and NSAIDs. He had been admitted to a local hospital and managed with empirical antibiotics for 3 days before being referred to our hospital for further evaluation. He was previously healthy and denied tobacco or alcohol use.

At admission, he was afebrile. Neurologic examination revealed the presence of left vocal cord palsy, deviation of tongue to the left side, and a decreased gag reflex, suggesting left IXth, Xth, and XIIth cranial nerve palsies. On otologic examination the tympanic membrane was intact without impairment of hearing capacity.

Laboratory testing revealed an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 6.58 mg/dL without leukocytosis. All other laboratory tests including hemoglobin, platelet count, hepatic enzymes, electrolytes, cerebrospinal fluid, VDRL, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer, D-dimer level and urinalysis were within normal range. A cranial MRI and MR venography showed left mastoiditis, venous thrombosis in the left transverse and sigmoid sinuses, thrombophlebitis and skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) (Fig. 1). Chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) showed multiple peripheral pulmonary nodules of varying degrees of cavitation in both lungs (Fig. 2). The patient was diagnosed of having atypical SBO caused by masked mastoiditis complicated by sigmoid sinus thrombosis and multiple septic pulmonary emboli, and intravenous (IV) piperacillin/tazobactam (18 g/day) and heparinization was started after 3 pairs of blood cultures were performed. Percutaneous needle aspiration (PCNA) biopsy of one cavitary consolidation was performed to exclude pulmonary tuberculosis, vasculitis, or fungal infection; the pathologic findings revealed many neutrophils and foamy histiocytes but no granuloma or fungal organisms, suggesting the existence of septic pulmonary emboli (Fig. 3). Fungal- and acid-fast bacillus-specific stains were negative. Enterobacter aerogenes was isolated from sputum culture. No organism was obtained from blood cultures.

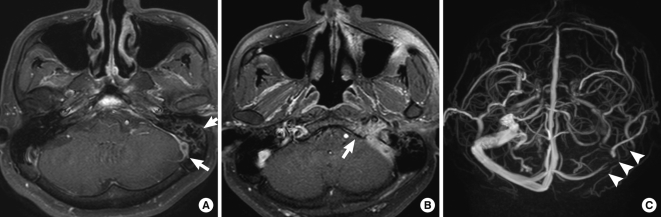

Fig. 1.

Cranial MRI of the case. (A) Gadolinium-enhanced fat saturation T1WI revealed left mastoiditis (short arrow) and a filling defect at the left sigmoid sinus (long arrow). (B) The arrow indicates diffuse enhancement in the left jugular fossa and the right side of the clivus, suggesting thrombophlebitis and skull base osteomyelitis. (C) MR venography demonstrated a decreased flow at the left transverse sinus, and an absence of flow at the distal portion of the left transverse sinus and the sigmoid sinus (arrowheads).

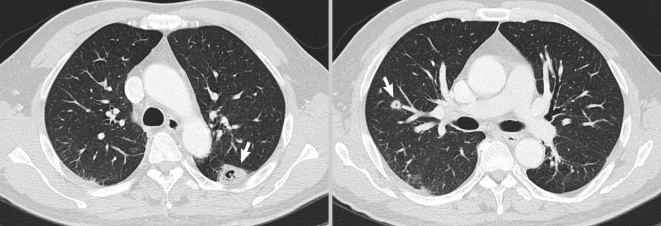

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographies of the chest show multiple peripheral pulmonary nodules with varying degrees of cavitation in both lungs (arrows).

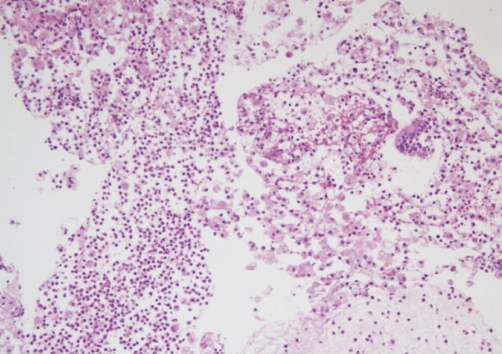

Fig. 3.

Histopathology of the lung biopsy reveals many neutrophils and foamy histiocytes. Hematoxylin-and-eosin stain (original × 100).

Upon discharge 1 month after admission, the patient's neurologic deficits were completely recovered, the CRP level returned to normal range and simultaneously conducted chest radiography and CT showed regression of the scattered pulmonary nodules (Fig. 4). Follow-up cranial MRI and venography also showed a decrease in the volume of thrombus in the sinus, compared to the previous study (Fig. 5). The patient was discharged on oral antibiotics (levofloxacin, 750 mg/day) and oral anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. Antibiotics were maintained for 5 weeks in conjunction with anticoagulants. Warfarin treatment was continued with a target INR being between 2 and 3, without hemorrhagic complications, over 1 yr. Follow-up cranial MRI and MR venography showed complete resolution of the thrombus in the sigmoid sinus. No recurrence has been noted 2 yr after hospital discharge.

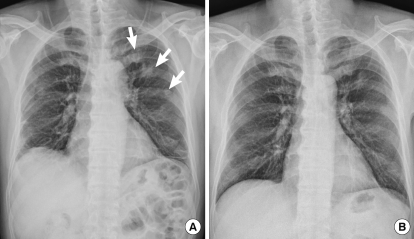

Fig. 4.

Chest X-ray findings. (A) Image on admission with multiple nodules in both lungs (arrows). (B) A repeat chest X-ray shows that the pulmonary lesions decreased in extent after commencement of antimicrobial therapy.

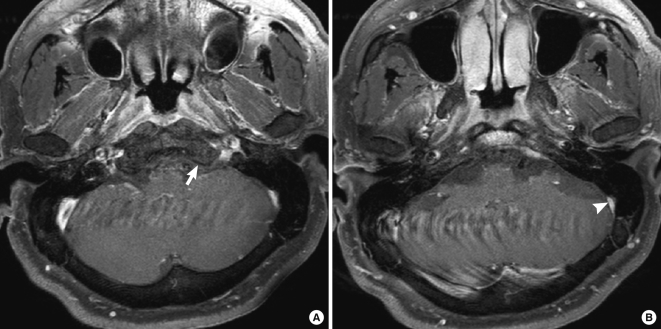

Fig. 5.

(A) Gadolinium-enhanced fat saturation T1WI reveals elimination of the diffuse enhancement in the left jugular fossa and adjacent bony structures (arrow). (B) Arrowhead indicates regression of the thrombus in the sinus.

DISCUSSION

The triad of osteomyelitis, deep venous thrombophlebitis and septic pulmonary embolism is a rare, but life-threatening syndrome that requires prompt recognition and treatment (6). Recognition of any one of the triad should prompt a search for the other associated conditions. Our patient, a 51-yr-old immunocompetent male, had SBO caused by masked mastoiditis complicated by sigmoid sinus thrombosis and a septic pulmonary embolism. Fortunately, he was successfully treated without surgical intervention.

SBO is usually found in patients with predisposing factors such as an immunocompromised state, diabetes mellitus, chronic mastoiditis, paranasal sinus infection, or necrotizing otitis externa (2). However, diagnostic difficulties may arise when immunocompetent patients present with headache and cranial nerve involvement, but without obvious infectious focus (1). Such patients have been considered to have atypical SBO because they do not initially present with malignant otitis externa (1). The cause of atypical SBO in our patient was a masked mastoiditis. This is a subclinical infectious inflammatory process of the mucosal lining and the bony structure of the mastoid air cells, with an intact tympanic membrane. The developing bone infection is probably caused by colonizing flora in this unventilated environment, is low-grade, and pus is not formed. An intact eardrum does not imply that bone-eroding disease within the mastoid is not severe.

Chronic mastoiditis may be a predisposing factor to SBO (2), sigmoid sinus thrombosis, or epidural abscess meningitis (3). The frequency of intracranial complications of acute mastoiditis was 6.8% in an earlier retrospective study (3).

Collet-Sicard syndrome (CSS) is a rare condition that includes palsies of cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII. A case of CSS related to SBO initially diagnosed as a cerebrovascular accident, was reported by Sibai et al. (7). Our patient complained of persistent headache and neurologic deficits such as left vocal cord palsy, deviated tongue to the left side, and a decreased gag reflex, making diagnosis more difficult.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa can cause SBO and mastoiditis, but the infection can also be mixed. E. aerogenes was isolated from the sputum of our patient. We assume that this organism was the cause of mastoiditis and SBO because we could not identify any other organism in blood cultures. This may be because of prior prescription of empirical antibiotics elsewhere. If this assumption may be acceptable, the present case constitutes, to the best of our knowledge, the first report of E. aerogenes as a pathogen causing SBO and mastoiditis.

No therapeutic criterion is available for the duration of antimicrobial therapy. Numerous reports have addressed this question, but opinions differ regarding the endpoint of treatment. An earlier study suggested that gallium scanning could be helpful in the evaluation of the response to therapy or disease recurrence (2). We successfully treated our patient with 4 weeks of IV piperacillin/tazobactam, and 1 further week of oral levofloxacin (750 mg/day), until the CRP level became normalized and the MRI and MR venographic evidences of SBO, mastoiditis, and sigmoid sinus thrombosis had significantly improved. We used MRI and MR venography for follow-up imaging and to assist in the decision-making on the endpoint of treatment, because a gallium scan does not reveal sigmoid sinus thrombosis. We consider that the septic pulmonary emboli of our patient arose from hematogenous dissemination of the sigmoid sinus thrombosis via the right side of the heart. A case of septic cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) accompanied by septic pulmonary emboli, has been reported (5). No consensus is available regarding the utility of anticoagulant treatment, or how long such therapy should be continued for septic CST patients, mainly due to the low possibility of performing prospective trials. However, a retrospective review of various reports indicated that intracranial hemorrhage caused by anticoagulation is rare, and that anticoagulation therapy can be safely used as an adjunct to antibiotic treatment if the clinical condition is deteriorating in the absence of hemorrhagic intracranial complications on imaging (8). We employed heparin and warfarin for anticoagulation, because the patient had septic pulmonary emboli and the symptoms became clinically aggravated despite antibiotics treatment. Treatment was successful, without any hemorrhagic complication; the sigmoid sinus thrombosis was completely resolved.

In conclusion, we report a case of masked mastoiditis complicated by atypical SBO, sigmoid sinus thrombophlebitis, and multiple septic pulmonary emboli in an immunocompetent adult, who was successfully treated with antibiotics for 5 weeks in conjunction with anticoagulation therapy. Early diagnosis is of utmost importance as medical treatment has a favorable prognosis and no surgical intervention is required.

References

- 1.Grobman LR, Ganz W, Casiano R, Goldberg S. Atypical osteomyelitis of the skull base. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:671–676. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler JR, Grobman L, Quencer R, Serafini A. Osteomyelitis of the base of the skull. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:245–251. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go C, Bernstein JM, de Jong AL, Sulek M, Friedman EM. Intracranial complications of acute mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;52:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt GR, Gates GA. Masked mastoiditis. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1034–1037. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198308000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoshino C, Satoh N, Sugawara S, Kuriyama C, Kikuchi A, Ohta M. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis complicated by narrowing of the internal carotid artery, subarachnoid abscess and multiple pulmonary septic emboli. Intern Med. 2007;46:317–323. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepage AA, Hess EP, Schears RM. Septic thrombophlebitis with acute osteomyelitis in adolescent children: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1:155–159. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibai TA, Ben-Galim PJ, Eicher SA, Reitman CA. Infectious Collet-Sicard syndrome in the differential diagnosis of cerebrovascular accident: a case of head-to-neck dissociation with skull-based osteomyelitis. Spine J. 2009;9:e6–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia K, Jones NS. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis: are anticoagulants indicated? A review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:667–676. doi: 10.1258/002221502760237920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]