Abstract

Background

New legislation in the U.S. prohibits tobacco companies from labelling cigarette packs with terms such as ‘light,’ ‘mild,’ or ‘low’ after June 2010. However, experience from countries that have removed these descriptors suggests different terms, colors, or numbers communicating the same messages may replace them.

Purpose

The main purpose of this study was to examine how cigarette pack colors are perceived by smokers to correspond to different descriptive terms.

Methods

Newspaper advertisements and craigslist.org postings directed interested current smokers to a survey website. Eligible participants were shown an array of six cigarette packages (altered to remove all descriptive terms) and asked to link package images with their corresponding descriptive terms. Participants were then asked to identify which pack in the array they would choose if they were concerned with health, tar, nicotine, image, and taste.

Results

A total of 193 participants completed the survey from February to March 2008 (data were analyzed from May 2008 through November 2010). Participants were more accurate in matching descriptors to pack images for Marlboro brand cigarettes than for unfamiliar Peter Jackson brand (sold in Australia). Smokers overwhelmingly chose the ‘whitest’ pack if they were concerned about health, tar, and nicotine.

Conclusions

Smokers in the U.S. associate brand descriptors with colors. Further, white packaging appears to most influence perceptions of safety. Removal of descriptor terms but not the associated colors will be insufficient in eliminating misperceptions about the risks from smoking communicated to smokers through packaging.

Introduction

Product packaging is an important tool for producers to communicate with consumers.1 Tobacco manufacturers have effectively used cigarette pack design, colors, and descriptive terms to communicate the impression of lower-tar or milder smoke while preserving taste ‘satisfaction’.2–5 Smokers’ beliefs about a given product are likely to be shaped in part by the descriptors, colors, and images portrayed on the pack and in related marketing materials. The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Article 11) calls for a ban on misleading descriptors in an effort to address consumer misperceptions about tobacco products.6 New regulations contained in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (FSPTCA) prohibit tobacco companies from labelling cigarette packs with terms such as ‘light,’ ‘mild,’ or ‘low’ after June 2010.7 However, experience from countries that have removed these descriptors suggests that cigarette marketers circumvent the intended goal of the regulation by using different terms, colors, or numbers to communicate the same messages.8, 9 Recent research has shown that consumers in the UK and Canada, which have removed ‘light’ and ‘mild’ descriptors, perceive cigarettes in packs with lighter colors as less harmful and easier to quit compared to cigarettes in packs with darker colors.10, 11

The main purpose of this study was to examine how different pack colors are perceived by U.S. smokers to correspond to different descriptors. Participants were shown a series of packs for a brand with which they are familiar as being heavily marketed and sold in the U.S. (Marlboro, Philip Morris USA) as well as a brand with which they are unfamiliar (Peter Jackson, Philip Morris International), sold in Australia. The purpose of selecting the unfamiliar Peter Jackson brand was twofold: first, participants were not expected to know, in advance of completing the survey, which descriptor terms matched which pack. Therefore, this study tested the participant’s ability to match the descriptor terms with packs and colors that are completely foreign to them.

Second, this study hypothesized that participants would be more likely to correctly match descriptors for a brand of cigarettes with which they are familiar, given the marketing they are exposed to with relation to that brand and the conditioning that occurs among the population from that marketing, compared to a brand for which they never see marketing materials. This hypothesis tests the value of removing the descriptor terms (such as ‘light’ and ‘ultra light’) from packs that participants are familiar with and can identify as such, absent of the term explicitly obvious on the pack.

Methods

Survey Administration

Data collection occurred from February through March 2008. Participants were recruited using newspaper advertisements and postings on CraigsList.org, which directed interested respondents to a survey website. A brief screening survey was used to determine eligibility for participation. Eligible participants were defined as current smokers (a ‘yes’ response to the question “Have you smoked at least 1 cigarette, even a puff in the last 30 days?”), aged ≥18 years, and not color blind. Colorblindness was determined using two questions, the first asking the participant if, to their knowledge, they are colorblind, and a second based on the Ishihara test, where the participant was presented with the number ‘74’ in green text embedded in a red background and had to input the text into a box. If the input text was correct, it was presumed that the participant was not colorblind. Participants then viewed a description of the study and could choose whether to continue or discontinue with the study.

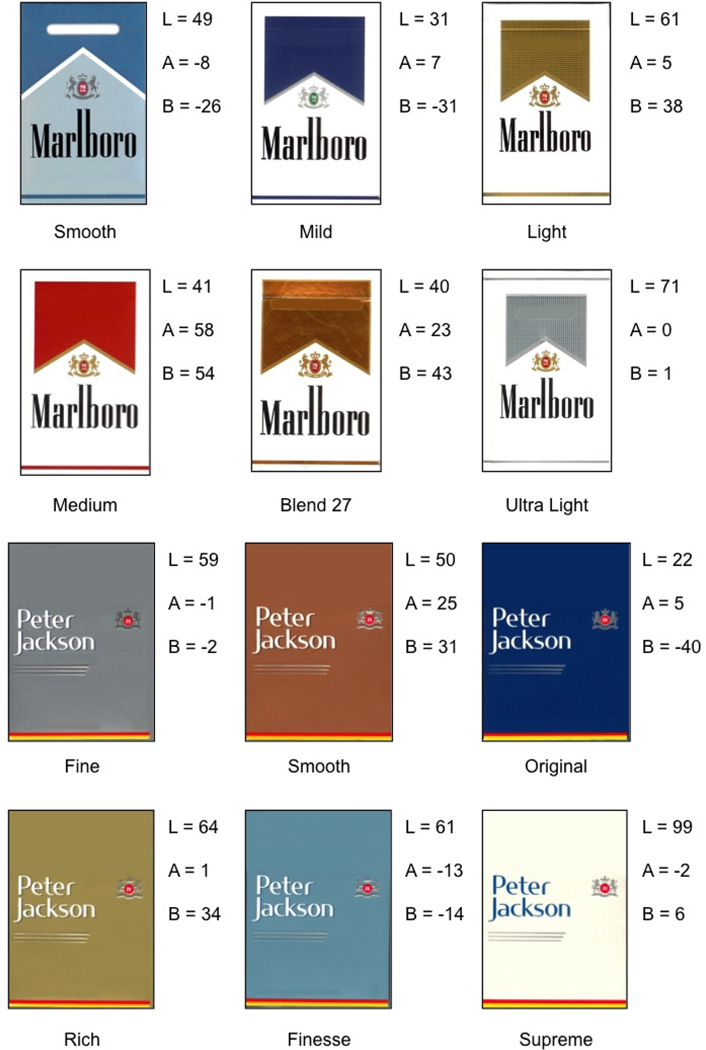

Participants then were shown an array of six cigarette packages which had been digitally altered to remove all descriptive terms with the exception of brand names (Figure 1). They were then asked to link the number listed next to each package image with one of the descriptive terms shown at the bottom of the page. Arrays of six-packs from two brands were presented—Marlboro (a brand familiar to U.S. smokers) and Peter Jackson (an Australian brand unfamiliar to U.S. smokers), in random order. Peter Jackson was examined as a control brand for two reasons: (1) Marlboro cigarettes would have a long history of association between words and colors for U.S. participants; and (2) Australia had already phased out traditional Light and Mild descriptors, so the Peter Jackson cigarettes used descriptors uncommon in the U.S. at the time of the study.

Figure 1.

Marlboro and Peter Jackson packages shown in the web survey with corresponding descriptors and CIELAB values.

L, lightness; A, red–green; B, blue–yellow

After linking pack images to descriptors, participants were asked to identify which pack in each brand array (Marlboro, Peter Jackson) they would choose if they were concerned with health, tar, nicotine, image, and taste (order of presentation randomized) with the following question: “Based on what you see, which of these packs would you choose if you were most concerned about…”. The pack arrays shown were the same as those shown for the descriptor matching task described earlier (Figure 1). Participants also completed a tobacco use history and a nine-item assessment of Need for Cognition, which relates to engagement in critical thinking.12, 13 The utility of this score was twofold: first, it allows for a proxy evaluation of the level of engagement of the respondent who is completing this web-based survey independently in an outside location; and second, it is reasonable to hypothesize that smokers with comparable Need for Cognition scores might process the colors on cigarette packs in similar ways. Participants were debriefed at the end of the survey and received a $20 check for their time. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute IRB.

Pack color quantification

Since a major objective of this project was to compare smokers’ perceptions of pack colors, objective assessments of color and color differences were needed. ‘CIELAB’, defined as the International Commission on Illumination LAB color space, is a three-dimensional color-opponent space where a color is described in reference to its values in three dimensions: dimension L is lightness and A (red–green) and B (blue–yellow) are the color components, meaning every color can be described in terms of 3 coordinates. It is this type of three-dimensional space that allows one to distinguish among shades of blue such as navy, aqua, and turquoise, or between dark red and bright red, for example. CIELAB coordinates were obtained from the images for defined regions in each pack—for Peter Jackson, this was the area next to the brand name, while for Marlboro this was the center of the ‘chevron’.

CIELAB values for each pack are provided in Figure 1. To quantify the extent to which two colors differ, one calculates CIELAB Delta E (ΔE), the Euclidian distance between two color values in the three-dimensional CIELAB color space, defined as: .14 It is dimensionless and represents an absolute difference in color, with larger values (increasing from 0) indicating larger differences. To provide a single-number score for each pack, a ΔE score was calculated relative to white (L=110, A=0, B=0). To assess the color gradient within a brand family as tar yields reduced, a between-pack ΔE score was also calculated comparing each pack to the member of the brand family with the highest tar level (Marlboro Smooth and Peter Jackson Original, respectively).

Statistical Analyses

Data preparation and analysis were conducted using SPSS Version 16.0 (Chicago, IL) from May 2008 through November 2010. Data files were cleaned to ensure that all participants met eligibility criteria (aged >18 years, did not report being colorblind, correct response to Ishihara test, current smoker). Descriptive statistics are reported for demographic and tobacco use characteristics, as well as frequencies for correct responses of descriptor term to pack image and word associations for each of the brands. Correlation was assessed with Spearman’s rho and agreement was assessed using Kendall’s tau-B. Wilcoxon tests were used to compare scores. In order to examine if performance on the pack-matching tasks (total and for each brand) were influenced by a person’s demographic and tobacco-use characteristics, a negative binomial regression analysis using a generalized estimating equations framework (log link, unstructured working correlation matrix) was performed.

The main outcome variable was the number of correctly matched packs (to descriptor term), with product rated considered a within-subjects repeated factor. In the negative binomial model, an offset equaling the natural logarithm of 6 (1.79176) was used so that findings would be expressed as a proportion correct. Logistic regression (binomial distribution, logit link, unstructured working correlation matrix) was used to examine factors associated with selecting packs on the basis of health, tar, and nicotine. Multivariate analyses were adjusted for age in years, gender (male; female), race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic; nonwhite and/or Hispanic race/ethnicity), current brand (Marlboro; Other), Heaviness of Smoking Index (range 0–6), and Need for Cognition (range 12–45). Significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 193 participants were eligible for and completed the web-based survey, with a median completion time of 23 minutes. Participants had a median age of 29 years (IQR 18 years), 57% were female, and 89% were non-Hispanic white. The three most commonly reported usual cigarette brands were Marlboro (32%), Camel (20%), and Newport (14%). Eighty-one percent reported smoking 20 cigarettes or fewer per day, and 62% reported smoking within 30 minutes of waking. Participants’ median Heaviness of Smoking Index 15 score was 3 (IQR 3). In terms of smoking-cessation behavior, 66% reported an intention to quit smoking in the future, and 64% reported at least one 24-hour quit attempt in the past year. The median Need for Cognition score was 33 (IQR 10), comparable to prior samples of smokers.13

Matching descriptive terms to packs

Across both brands, participants matched a median of 5 (IQR 3) packs correctly to descriptors, or about 42%. Participants were more accurate in matching descriptors to pack images for Marlboro brand cigarettes (median 4 correct, IQR 2) than for the unfamiliar Peter Jackson (median 1 correct, IQR 1.5) [Wilcoxon Z =−10.66, p<0.001]. In a negative binomial regression model controlling for other factors, this difference in accuracy was maintained (61% correct for Marlboro vs 20% for Peter Jackson, B=−1.299, p<.001). Proportion of packs correctly identified was inversely related to age [B=−0.009, p=0.003], and positively related to Need for Cognition score [B=0.010, p=0.030]. A significant interaction was also observed between current product used (Marlboro vs other brands) and brand being rated [B=0.333, p=.033]. Marlboro smokers were more accurate in matching Marlboro packs to brand descriptors compared to other brand smokers (63% vs 60%) and less accurate in matching Peter Jackson packs to descriptors (17% vs 23%). No significant effects were detected of gender [B=−0.087, p=0.180], race/ethnicity [B=0.150, p=0.159], or HSI score [B=0.031, p=0.127].

Pack color and consumer perceptions

Table 1 shows ΔE scores for each pack relative to white and relative to the highest-tar member of the brand family. No discernable patterns were seen for ΔE scores relative to the highest-tar variety within or across brands—the observed variability is likely explained by the use of different color schemes within brand families and would have diminished if brand families utilized different shades of the same color to differentiate varieties (e.g., different shades of blue among packs in a brand). However, across brands, color difference relative to white correlated strongly with tar yield, suggesting increasing ‘whiteness’ as tar yields decrease [rS = 0.78, p=0.003].

Table 1.

Delta-E scores and health, tar, and nicotine ratings by brand.

| Brand | Tar25 (mg) |

ΔE from white |

Between- pack ΔE |

Healtha (%) |

Tarb (%) |

Nicotinec (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marlboro Smooth | 15 | 57.8 | ref | 10.90 | 13.50 | 16.60 |

| Marlboro Blend 27 | 12 | 77.3 | 76.18 | 4.10 | 3.10 | 2.60 |

| Marlboro Medium |

11 | 98.8 | 104.02 | 8.30 | 9.30 | 23.80 |

| Marlboro Mild | 11 | 76.0 | 23.96 | 3.10 | 1.60 | 4.10 |

| Marlboro Light | 10 | 54.7 | 66.40 | 5.20 | 7.30 | 5.20 |

| Marlboro Ultra Light | 6 | 29.0 | 35.74 | 67.90 | 64.20 | 47.70 |

| Statistical test* | χ2 (5) | 372.3 | 331.0 | 173.6 | ||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| PJ Original | 12 | 87.8 | ref | 4.10 | 12.40 | 8.80 |

| PJ Rich | 8 | 49.5 | 85.18 | 7.30 | 7.80 | 5.20 |

| PJ Smooth | 6 | 63.9 | 78.90 | 3.60 | 6.70 | 9.80 |

| PJ Fine | 4 | 41.1 | 53.38 | 17.10 | 16.60 | 21.80 |

| PJ Finesse | 2 | 43.4 | 50.21 | 6.70 | 3.60 | 7.80 |

| PJ Supreme | 1 | 6.4 | 89.97 | 60.60 | 51.80 | 46.10 |

| Statistical test* | χ2 (5) | 284.6 | 187.3 | 141.1 | ||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Bold entries indicate significant differences were detected, p-value<0.001.

Measure was assessed with the question: “Based on what you see, which of these packs would you choose if you were most concerned about health?”

Measure was assessed with the question: “Based on what you see, which of these packs would you choose if you were most concerned about tar?”

Measure was assessed with the question: “Based on what you see, which of these packs would you choose if you were most concerned about nicotine?”

Chi-square test of distribution (null assuming equal cell sizes)

Chi-square tests also found that smokers consistently chose the ‘whitest’ pack in both arrays (i.e., lowest ΔE relative to white; Marlboro Ultra Light and Peter Jackson Supreme) if they were concerned about health (68% for Marlboro, 61% for Peter Jackson), tar (55% for Marlboro, 45% for Peter Jackson), and nicotine (48% for Marlboro, 46% for Peter Jackson). In logistic regression models (see Table 2), there was no influence of demographic factors, nor a difference by brand, for selection of packs for health or nicotine. However, for concern about tar, the whitest Marlboro pack was more likely to be selected that the whitest Peter Jackson pack, and women and those with higher Need for Cognition scores were more likely overall to select the whitest pack for concern about tar.

Table 2.

Logistic regression results examining correlates of selecting the ‘whitest’ pack for concern about health, tar, and nicotine

| Health | Tar | Nicotine | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | ORa | 95% CI | p | OR* | 95% CI | p | OR* | 95% CI | p | |

| Product | Marlboro | 1.38 | 0.93,2.06 | 0.114 | 1.73 | 1.18, 2.56 | 0.005 | 1.02 | 0.71, 1.45 | 0.932 |

| P. Jackson | ref | ref | ref | |||||||

| Gender | Female | 1.08 | 0.19, 3.49 | 0.770 | 1.83 | 1.10, 3.03 | 0.019 | 1.07 | 0.65, 1.75 | 0.793 |

| Male | ref | ref | ref | |||||||

| Race | Nonwhite | 0.99 | 0.43, 2.28 | 0.990 | 0.72 | 0.29, 1.75 | 0.465 | 0.45 | 0.19, 1.07 | 0.070 |

| White | ref | ref | ref | |||||||

| Usual brand | Marlboro | 1.31 | 0.76, 2.26 | 0.334 | 1.32 | 0.75, 2.33 | 0.330 | 1.38 | 0.80, 2.38 | 0.246 |

| Other | ref | ref | ref | |||||||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 | 0.866 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.421 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.281 | |

| HIS | 1.16 | 0.98, 1.36 | 0.077 | 1.08 | 0.93, 1.26 | 0.332 | 1.09 | 0.93, 1.27 | 0.288 | |

| Need for Cognition | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.04 | 0.851 | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.09 | 0.014 | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.469 | |

Bold entries indicate significant differences were detected, p-value<0.05.

ORs adjusted for all variables in the model.

HSI,

Discussion

Overall, this survey found that smokers in the U.S. associate brand descriptors with colors when they are familiar with the brands, even when controlling for person-level covariates. Further, whiter packaging appears to most influence perceptions of safety. This finding is not unique to this study as demonstrated by unpublished internal marketing research conducted by Philip Morris nearly 2 decades ago.16, 17 Therefore, removal of descriptor terms but not the associated colors may be insufficient in eliminating misperceptions about the risks from smoking communicated to smokers through packaging.

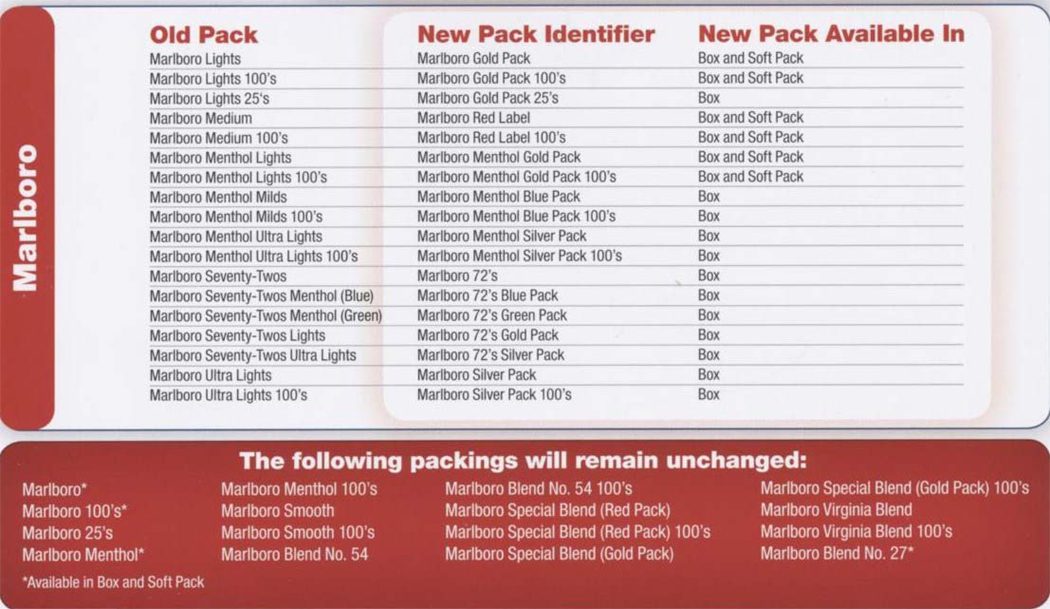

As described by Anderson et al18, a great deal of the impact related to the RICO ruling will be based on the interpretation of the guidelines set forth by Judge Kessler regarding “any other words which reasonably could be expected to result in a consumer believing that smoking the cigarette brand using that descriptor may result in a lower risk of disease or be less hazardous to health than smoking other brands of cigarettes”. If the order is “narrowly interpreted,” evidence from other countries suggests tobacco companies will employ packaging, and advertising imagery to communicate these same messages to consumers. As Figures 1 and 2 of the manuscript illustrate, the industry has already moved in the direction of using color to communicate with smokers on packs that were formerly labeled “light” and “ultra light”. Based on these findings, it is suggested that the RICO ruling be interpreted broadly to include not only the words themselves but long-associated colors.

Figure 2.

List created by Philip Morris U.S.A. outlining anticipated changes to descriptor terms on packs in U.S. after June 2010.

Older smokers were found less likely to correctly match cigarettes correctly with the descriptor terms. Historically to current day, cigarette marketing in the U.S. for brands, including Marlboro, have targeted youth and young adults.19 Therefore, it is possible that younger respondents were more likely to correctly match the Marlboro descriptors with the packs as a result of intense marketing efforts made with this subsample of the population. Further, women were found more likely to select white packs out of concern for tar. This is consistent with prior work showing women are more likely to smoke lower-tar cigarettes, and that brands directed at women tend to use lighter colors.

In jurisdictions that have banned specific terms such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’, industry has replaced banned descriptors with numbers and color names,8–11 and companies in the U.S. have recently implemented color replacements as well. Philip Morris U.S.A. recently created a code sheet for each of their retailers, equating the “Old Pack” descriptor with the anticipated “New Pack Identifier” (Figure 2) (G. Connolly, Harvard School of Public Health, personal communication, 2/16/2010). This document outlines their plan to substitute descriptor terms such as ‘light’ with ‘gold’ and ‘ultra light’ with ‘silver’.

Further, PM introduced pack ‘onserts’ communicating to consumers that the descriptors of their brands had changed, and instructing them to “ask for Marlboro in the gold pack” in the future.20 This prompted FDA to request information from the company about consumer perceptions of pack colors,21 noting that “[b]y stating that only the packaging is changing, but the cigarettes will stay the same, the onsert suggests that Marlboro in the gold pack will have the same characteristics as Marlboro Lights, including any mistaken attributes associated with the “light” cigarettes.” FDA recently sent a similar request for information from Commonwealth Brands for promotional materials distributed and available on their website regarding their similar changes in labeling of “Lights” and “Ultra Lights” products.22

The industry argues that the colors and descriptors define real differences in product taste (strength), but independent studies, including this one, show colors and descriptors are perceived by smokers to communicate health-risk information.11 Indeed, this study observed that concern for health was significantly correlated with concern about tar and nicotine, and in all three cases the lightest pack was selected by those concerned about each. There were few demographic correlates of this behavior, suggesting the tendency to associate whiter packs with health may be widespread among smokers. While a court ruling has rejected the blanket ban of color in cigarette advertising contained in the FSPTCA23 (as of this writing, the case remains under appeal), accumulating evidence suggests that the FDA should investigate whether the use of brand color coding schemes should be restricted in the same way as brand descriptors that may mislead consumers. The findings of this study also lend further support for movement toward plain packaging of cigarettes.24

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, 5R21CA101946-2. KMC has served in the past and continues to serve as a paid expert witness for plaintiffs in litigation against the tobacco industry.

Footnotes

No other authors reported financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Underwood RL, Ozanne J. Is your package an effective communicator? A normative framework for increasing the communicative competence of packaging. Journal of Marketing Communications. 1998;4(4):207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. Marketing cigarettes with low machine-measured yields. In: DHHS NIoHNCI, editor. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph 13: Risks Associated with Smoking Cigarettes with Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine. Bethesda, M.D: DHHS; 2001. pp. 199–233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. The dark side of marketing seemingly "Light" cigarettes: successful images and failed fact. Tob Control. 2002 March;11 Suppl 1:I18–I31. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slade J. The pack as advertisement. Tob Control. 1997;6(3):169–170. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002 March;11 Suppl 1:I73–I80. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: Switzerland: WHO Document Production Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.; H.R.1256, H.R.1256–111th Congress; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.King B, Borland R. What was "light" and "mild" is now "smooth" and "fine": new labelling of Australian cigarettes. Tob Control. 2005 June;14(3):214–215. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peace J, Wilson N, Hoek J, Edwards R, Thomson G. Survey of descriptors on cigarette packs: still misleading consumers? N Z Med J. 2009;122(1303):90–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond D, Dockrell M, Arnott D, Lee A, McNeill A. Cigarette pack design and perceptions of risk among UK adults and youth. Eur J Public Health. 2009 September 2;19:631–637. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond D, Parkinson C. The impact of cigarette package design on perceptions of risk. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009 September;31(3):345–353. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manfredo MJ, Bright A. A model for assessing the effects of communication on recreationists. J Leisure Res. 1991;20:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shadel WG, Lerman C, Cappella J, Strasser AA, Pinto A, Hornik R. Evaluating smokers' reactions to advertising for new lower nicotine quest cigarettes. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006 March;20(1):80–84. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brainard DH. Color Appearance and Color Difference Specification. In: Shevell SK, editor. The Science of Color. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2003. p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989 July;84(7):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philip Morris USA, Lalley K, Eisen K, Bonhomme J. Marketing Research Department Report: Marlboro Ultra Lights Qualitative Research. Report No.: Bates No. 2040802520-2040802523. 1988 Aug;22

- 17.Philip Morris USA, Halpern M. Interoffice correspondence: Literature Review--Color. 1994:2–25. Ref Type: Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson SJ, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Implications of the federal court order banning the terms "light" and "mild": what difference could it make? Tob Control. 2007 August;16(4):275–279. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK, Steger C, Leavell NR. Marketing to America's youth: evidence from corporate documents. Tob Control. 2002 March;11 Suppl 1:I5–17. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson D. F.D.A Seeks Explanation of Marlboro Marketing. Vol. 17. New York Times; 2010. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 21.Center for Tobacco Products FUDoHaHS. Letter to Philip Morris USA, Inc., Marketing Marlboro Lights Cigarettes with an Onsert. 2010 June;17 http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm216154.htm.

- 22.Center for Tobacco Products FUDoHaHS. Letter to Commonwealth Brands, Inc., Promotional Materials Disseminated Through the Company's. 2010 July;20 Website. http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm219891.htm.

- 23.Reuters. U.S. judge strikes part of tobacco ad, label law. 2010 http://www reuters com/article/idUSTRE6045A520100105.

- 24.Freeman B, Chapman S, Rimmer M. The case for the plain packaging of tobacco products. Addiction. 2008 April;103(4):580–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor RJ, Hammond D, McNeill A, et al. How do different cigarette design features influence the standard tar yields of popular cigarette brands sold in different countries? Tob Control. 2008 September;17 Suppl 1:i1–i5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]