Abstract

This study investigated how parental beliefs about children’s emotions and parental stress relate to children’s feelings of security in the parent-child relationship. Models predicting direct effects of parental beliefs and parental stress, and moderating effects of parental stress on the relationship between parental beliefs and children’s feelings of security were tested. Participants were 85 African American, European American, and Lumbee American Indian 4th and 5th grade children and one of their parents. Children reported their feelings of security in the parent-child relationship; parents independently reported on their beliefs and their stress. Parental stress moderated relationships between three of the four parental beliefs about the value of children’s emotions and children’s attachment security. When parent stress was low, parental beliefs accepting and valuing children’s emotions were not related to children’s feelings of security; when parent stress was high, however, parental beliefs accepting and valuing children’s emotions were related to children’s feelings of security. These findings highlight the importance of examining parental beliefs and stress together for children’s attachment security.

Keywords: Parental Beliefs, Stress, Attachment security

Secure attachment is thought to provide children with a close emotional relationship and a secure base from which to explore their environment (Ainsworth, 1979). Through this relationship children also develop a mental schema of their self, their attachment figure, and relationships in general (Ainsworth, 1979; Bowlby, 1980). The importance of children’s sense of security in relationships with parents has been demonstrated in a myriad of studies investigating cognitive, emotional, and social development (e.g. Allen, Porter, McFarland, McElhaney, & Marsh, 2007; Cassidy, 1994; Diener, Isabella, Behunin, & Wong, 2008; Kerns & Richardson, 2005; McQuaid, Bigelow, McLaughlin, & MacLean, 2008).

Emotion is central to parenting (Dix, 1991) and researchers in the fields of attachment (e.g. Bretherton, 1990) and emotion (e.g. Tomkins, 1962; 1963) have consistently identified how these two constructs are inextricably linked. The organization of the attachment relationship begins in infancy, when caregivers’ emotion-related behaviors including expressiveness, warmth, responsiveness, and sensitivity to distress are powerful predictors of children’s attachment security (e,g, Ainsworth, 1979; Bowlby, 1980; Laible, 2006; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). In middle childhood, the attachment relationship is somewhat different, in part due to children seeking more autonomy from their parents (Allen & Land, 1999), their increasingly complex understanding of the self (Harter, 1999), and more advanced emotion understanding and regulation (Murphy, Eisenberg, Fabes, Shepard & Guthrie, 1999; Saarni, 1999). Nevertheless, children’s perceptions of their parents as emotionally available, open to communication about emotions, and responsive to their emotions continues to be important (Bowlby, 1980; Bretherton, 1985; 1990; Cassidy, 1994; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn 1997; Kerns & Richardson, 2005), with children in middle childhood choosing parent attachment figures over peers to help them deal with negative emotions (Kerns, Tomich, & Kim, 2006).

Although children in middle childhood continue to rely on and benefit from parents’ emotion-related support, parents of children at this age vary in how much they accept and value their children’s emotions (Dunsmore, Her, Halberstadt, & Perez-Rivera, 2009). Given the importance of parents’ responsiveness to children’s emotions, parents who have core beliefs that children’s emotions are of value are likely to have children who report greater attachment security.

Indeed, parental beliefs about children’s emotion are thought to play a central role in guiding parental behaviors (Dix, 1991; Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad 1998; Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996; Parke & McDowell, 1998; Parker et al., 2010), which, in turn, are thought to be associated with important emotion-related outcomes for children (Dix, 1991; Dunsmore & Halberstadt, 1997; Eisenberg et al.1998; Gottman et al., 1996). Theory and evidence described below supports the notion that parental beliefs about emotion may well initiate the relationship between parents’ emotion socialization behaviors and children’s attachment security (Dunsmore & Halberstadt, 1997). Thus, the current study took the first step of assessing parental beliefs as a possible avenue for understanding the family socialization environment that influences children’s attachment security.

Parental Beliefs

There is increasing evidence that children’s understanding of their social relationships is cultivated by parental beliefs about children’s emotions. For example, parental emotion-related beliefs predict children’s peer relationships (Gottman et al., 1996; Wong, Diener, & Isabella, 2008), use of social support in response to stress (Halberstadt, Thompson, Parker, & Dunsmore, 2008), emotion understanding (Dunsmore et al., 2009; Dunsmore & Karn, 2001; 2004), and emotion regulation (Gottman et al., 1996; Halberstadt et al., 2008). Thus, parental beliefs may also influence the complex and intricate processes through which children come to understand their relationship with their parents.

Previous studies have identified four independent parental beliefs related to the value of children’s emotions (Halberstadt, Dunsmore, Thompson, Beale, Parker, & Bryant, 2010; Parker et al., 2010). Two beliefs concern the value of positive emotions and the value of negative emotions in children. Parents who value children’s positive and negative emotions believe that these emotions are useful and worthy of attention. It is important to note that parents who value children’s emotions do not necessarily believe that children should express all positive and negative emotions; rather they endorse beliefs that emotion-related experiences are beneficial. In contrast, parents who believe that children’s emotions are dangerous or problematic endorse the belief that emotion is not useful in most situations and should be avoided. The final value belief is similar to parents’ laissez-faire philosophy within the meta-emotion literature (Gottman et al., 1996; Hakim-Larson, Parker, Lee, Goodwin, & Voelker, 2006) and includes parents’ thinking that children’s emotions are just a part of life.

With regard to children’s security, parental beliefs about the value of emotion may impact how children feel about their parents. Parents who value children’s positive and negative emotions react in accepting ways and encourage children’s sharing of their emotional experience and expression (Gottman et al., 1996; Wong, McElwain, & Halberstadt, 2009), which are behaviors that have consistently defined secure attachments (Bretherton, 1990; Cassidy, 1994). Their children are then likely to feel more positive about their relationships with the knowledge that their parents are interested in and value their feelings. When parents believe that children’s emotions are not valuable, or are problematic in some way, they may react to children’s emotions by ignoring, suppressing, or denying them and, thus, children would feel less secure and more negative about their relationship. Finally, parents who believe that children’s emotions are a part of life may acknowledge emotions without evaluating them as good or bad, and may foster open communication with children about their emotions, which then contributes to children’s feelings of security.

We predicted that children whose parents value positive and negative emotion experience and expression would have a greater sense of security than children whose parents do not value these emotions. Further, children whose parents believe that emotional experience and expression tends to be problematic or dangerous would have a lower sense of security than children whose parents do not endorse that belief. Finally, children whose parents acknowledge that emotions are a normal part of life experience would be more securely attached than children whose parents believe that emotions are not a part of life experience.

Parental Stress

Parental stress is thought to have a spillover effect into the parent-child relationship. To illustrate, the more stress parents experience, the less supportive and more nonsupportive they are in response to children’s negative emotions (Nelson, O’Brien, Blankson, Calkins, & Keane, 2009). In the family-work literature, mothers who reported greater workloads or levels of interpersonal stress at work were described, by themselves and by independent observers, as being more behaviorally and emotionally withdrawn (Repetti & Wood, 1997). Interpersonal relationship stressors are also associated with greater parent-child tension (Almeida, Wethington, & Chandler, 1999). Finally, in a sample of mothers and infants, relationship stress was negatively related to infant attachment security (Coyl, Roggman, Newland, 2002) and indirectly related through maternal depression and spanking.

In summary, previous studies of attachment indicate that parents’ reported stress plays a role in children’s attachment status. Further, because parents who experience stressful events seem to have more negative emotion, less energy, emotional support, and patience to offer during parent-child interactions, their children may perceive them as being less sensitive and responsive to their emotions. Thus, we predicted that children whose parents experienced high levels of daily stress would report less secure feelings in the parent-child relationship, compared to children whose parents did not experience high levels of daily stress.

Parental Beliefs and Stress

As suggested above, parental beliefs and parental stress may have their own individual impact on children’s feelings of security, but they may also converge to have a joint, unique impact on children’s sense of security. When parents are stressed, and are thus less resilient in the face of their own negative feelings or the negative feelings of their children, their beliefs may become more apparent. For example, parents may be patient with their children’s emotions in low stress conditions whether or not they value children’s emotions. As their own stress increases, however, parents who do not value their children’s emotions may reduce their emotional availability and responsiveness to their children, as they do not see that investment as important in the face of other challenges depleting their emotional reserves. In comparison, parents who do value their children’s emotions may maintain or even increase their emotional availability and responsiveness to their children during stressful times. These parents are more likely to perceive their children’s emotions as worthy and important, despite constraints on their time and energy. Thus, when parental stress is high, parental belief systems may become more apparent in their responses to children’s emotions, which, in turn, impacts children’s perceptions of security with their parents.

In summary, we predicted that parental beliefs about children’s emotions and parental daily stress would both relate directly to children’s sense of security in the parent-child relationship. Further, we predicted that parental stress would moderate the relationship between parental beliefs about emotions and children’s attachment security, such that the relationship would be strongest when parents were also experiencing stress in their daily lives.

To test these hypotheses, parents reported on their beliefs about the value of children’s emotions and their experience of stress in the last 24 hours in a variety of domains. Children independently reported on their feelings of security in the parent-child relationship. We tested for four different kinds of beliefs about the value of children’s emotions, using a recently developed questionnaire. We tested for parental stress with a 7-item measure of daily stress. This brief measure demonstrates moderate to strong relationships with both chronic stress (e.g., Serido, Almeida, & Wethington, 2004) and mood (Eckenrode, 1984), suggesting that daily stress reflects longstanding conditions and may impact parents’ emotional support and availability. We measured children’s feelings of security with a well-established self-report measure of attachment security for children in middle childhood.

As noted above, we were particularly interested in parental beliefs and stress because they are thought to play important roles in guiding parental behaviors. In this exploratory study, we did not measure parental behaviors. Although parental beliefs and stress must be expressed in some verbal or behavioral form for children to experience them, capturing those behaviors is a nontrivial process. Creating emotional experiences and then assessing the multiple pathways by which beliefs and stress may be expressed through parental behaviors (e.g., discussing children’s strongly felt emotions, reacting to children’s emotions) in lab settings would be challenging. Observing parenting behavior in response to naturally-occurring emotionally-laden interactions in a home or community setting is cost- and time-prohibitive. Additionally, related research on parental beliefs, parental behaviors, and children’s coping strategies indicated that parental beliefs were stronger indicators of children’s coping strategies than were parental behaviors (Halberstadt et al., 2008), suggesting that parents’ ability to summarize their beliefs in a questionnaire may sometimes be a stronger predictor of children’s outcomes than assessments of parental behaviors in a single setting.

We were interested in middle elementary school aged children because they are demonstrating greater autonomy in the family, yet parents remain an important source for emotional feedback and support. There has also been increased focus on understanding the parent-child relationship in this age group, particularly regarding attachment security (e.g., Kerns, Tomich, Aspelmeier, & Contreras, 2000; Kerns et al., 2006). In addition, we chose to invite families from two regional ethnic groups to respond to a call for more ethnic diversity in psychological research.

Method

Participants

A total of 85 parent-child dyads participated (48% African American, 6% European American, and 46% Lumbee American Indian parent-child dyads; 40% mother-daughter dyads, 42% mother-son dyads, 13% father-son dyads, and 5% father-daughter dyads). The African American and European American families were recruited from a medium-sized Southern metropolitan area. Lumbee families were recruited from the Robeson County area in North Carolina where a large proportion of Lumbee reside.1 Recruitment strategies included contacting parents who had participated in previous studies, announcements at local churches and organizations such as the Boys and Girls Club, flyers in public locations, invitations to parents attending recreational sports practices such as Pop Warner football, and emails via online web listings and university alumni organizations.

Parents’ average age was 38.57 (range 28 to 53) years. All parents had completed high school, and many had completed college (mean years of education = 16.31, SD = 2.27 range = 12 to 21 years). Family yearly income ranged from $20,000 to $200,000 with a median of $62,500. Children were in 4th or 5th grade (M = 9.61 years, range = 8 to 11 years).

Procedure

Parents and children were greeted as they arrived at a university laboratory, and given time to feel comfortable in the setting. Children were asked to fill out the Security Scale along with other measures unrelated to the current study. Interviewers assisted by reading each item to the child as the child read along on their own sheet. Then the child selected the most appropriate answer about their relationship with the parent accompanying them in the study. Parents went to an adjoining room to complete the two questionnaires described below; then they participated in other activities unrelated to the current study. The entire session lasted approximately 1 to 1½ hours. For their participation, parents received $25 and children received $5 and a small gift. A racially mixed group of researchers assisted during data collection.

Measures

Parental beliefs about children’s emotions (PBACE)

The PBACE questionnaire was developed in previous studies, beginning with focus groups (Parker et al., 2010) followed by exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of responses from 1108 parents from three ethnicities (African American, European American, and Lumbee American; Halberstadt et al., 2010). Eleven scales, representing a variety of parental beliefs about emotion emerged.

In the present study, the four scales assessing the value of children’s emotions were used because of their direct relevance to children’s attachment security. These four distinct beliefs, followed by reliability and sample items are: 1) negative emotions are valuable: α = .80, “Feeling sad helps children to know what is important to them”; 2) positive emotions are valuable: α = .80; “It is important for children to express their happiness when they feel it”; 3) all emotions are problematic or dangerous: α = .81, “Children who feel emotions strongly are likely to face a lot of trouble in life”; and 4) emotions just are a part of life, neither good nor bad: α = .86, “Showing emotions isn’t a good thing or a bad thing; it’s just a part of being human”. Parents responded to all 45 items on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. For each factor, higher scores represent greater agreement with that belief.

Convergent and discriminant validity for these scales is promising. For example, the parental belief that negative emotions are valuable relates to parents’ encouraging, emotion-focused, and problem-focused reactions to children’s negative emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2010). The belief that positive emotions are valuable relates negatively with parents’ discomfort with children’s positive emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2010). Further, the parental belief that children’s emotions are problematic or dangerous was associated with parents’ greater masking of their own facial expressions while watching emotion-inducing films and knowing that their children were watching their faces (Dunsmore et al., 2009), as well as with parents’ greater distress, punitive, and minimization reactions to children’s negative emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2010). Finally, the parental belief that emotions are just a part of life was associated with parents encouraging, emotion-focused, and problem-focused reactions to children’s negative emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2010). None of the relationships between the four PBACE scales and constructs such as alexithymia, anxiety, and depression were significant. One significant correlation with social desirability emerged, suggesting that parents who perceived that emotions are dangerous scored lower in social desirability

Parental stressors

The Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002) includes seven different life stressors; parents responded “yes” or “no” to indicate if they had experienced those stressors in the past 24 hours. Some examples from the DISE are: “In the last 24 hours did you have an argument or disagreement with anyone?”, and “Did anything happen in your workplace or volunteer setting that most people would consider stressful?” The sum of the “yes” items constitutes the total score and, thus, higher scores indicate more perceived stressor exposure. In addition, parents were asked to determine how typical the last day was compared to other days. Most parents (75%) reported that the day was “somewhat” to “very similar”. Only four parents reported the day was not at all similar to other days, suggesting that this measure stress reflects longstanding conditions in the family.2 Overall daily stressors and specific types of daily stressors reported on the DISE, such as interpersonal tensions and network stressors, have been shown to predict health symptoms, cognitive functioning, well-being and mood, suggesting reasonable construct validity (Almeida et al., 2002; Neupert, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2008; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007; Piazza, Charles, Almeida, 2007).

Children’s attachment security

The 15-item Security Scale (Kerns, Klepac, & Cole, 1996) is designed to tap components of the attachment relationship that reflect the security of attachment in middle childhood. Children are first asked which of two statements is more like them, such as “Some kids find it easy to trust their mom (dad)” BUT “Other kids are not sure if they can trust their mom (dad)”. Once they choose the statement that is more like them, they determine if this statement is “really true” or “sort of true” for them. Thus, item responses range from 1 to 4, and these are summed to derive the final score. Higher scores represent greater security in the parent-child relationship. The measure has been validated with middle childhood/preadolescent children using projective measures of attachment (Granot & Mayseless, 2001), and theoretically related constructs, such as children’s friendship quality, peer acceptance, perceptions of their competence, self-esteem, and preoccupied and avoidant coping (Diener et al., 2008; Granot & Mayseless, 2001; Kerns et al., 1996). Stability of children’s reports of security has been demonstrated over a 2-week period with mothers (Kerns et al., 1996) and 2-year period with fathers, but not mothers (Kerns et al., 2000). Reliability of the Security Scale in the current study was acceptable, α = .79.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.3 Intracorrelations between the four types of parent beliefs indicate low to moderate relations; see Table 1. Because most of the correlations were not strong (absolute median r = .18), and the parental beliefs are theoretically distinct from one another, the subscales were not combined.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Parent and Child Measures (N = 85)

| Negative valuable (12 items) | Positive valuable (10 items) | Emotions dangerous (13 items) | Emotions part of life (10 items) | Parent Stress (7 items) | Child security (15 items) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions are valuable | 4.37 (.71) | .23* | −.27* | .51* | .21 | .13 |

| Positive emotions are valuable | 5.68 (.34) | .03 | .07 | .14 | −.03 | |

| Emotions are dangerous | 2.98 (.80) | −.12 | −.07 | −.21 | ||

| Emotions are part of life | 5.67 (.77) | .21 | .19 | |||

| Parent stress | 3.06 (1.79) | .05 | ||||

| Child security | 50.13 (6.78) |

p < .05

Note: Means and standard deviations are along the diagonal. Parent belief subscale scores can range from 1 to 6; parent stress from 1 to 7; and child security from 15 to 60.

Intercorrelations and MANOVAs were conducted with parental beliefs, parental stressors, and child attachment security, and the demographic variables (parent age, education, income, and sex; child sex and ethnicity). The belief that all emotions are problematic or dangerous was negatively related with education and age, rs = −.42 and −.30, ps < .001 and .05, respectively. Fathers reported greater belief than mothers that emotions are dangerous, F(1, 74) = 4.74, p < .05, η2 = .06, with no differences for ethnicity or child sex. There were no demographic differences for parental stress or children’s attachment security. Because we had no hypotheses about the demographic variables, nor were they related to the child outcome variable, they were not considered further.

Relations Between Parental Beliefs, Parental Stress, and Children’s Attachment Security

Regression analyses tested for direct relationships between parental beliefs and children’s attachment security, and between parental stress and children’s attachment security. Regression analyses also tested for moderation of parental stress on the relationship between parental beliefs about children’s emotions and children’s sense of security. To reduce nonessential multicollinearity, the independent variables (parental beliefs and parental stress) were centered (Aiken & West, 1991). An interaction term was also created with each parent belief and parental stress, resulting in a total of four interaction terms. Children’s attachment security was the outcome variable. The main effects for each parent belief and parental stress were entered in step one, and the interaction term was entered in step two. When interactions occurred, follow-up simple slope tests were conducted to explore the nature of the significant interactions (Aiken & West, 1991; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006).

As shown in Table 2, only one parent belief was directly related to children’s attachment security. The belief that children’s emotions are just a part of life and are neither good nor bad was positively related to children’s attachment security, suggesting that when parents report greater acceptance of children’s emotion as just a part of life, children have stronger feelings of security in the parent-child relationship. Parental stress was not directly related to children’s attachment.

Table 2.

Regression Analysis Predicting Moderation for Parental Beliefs, Parental Stressors, and Children’s Attachment Security (N = 85)

| Predictors | B | SE | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Negative emotions are valuable | 1.13 | 1.02 | .12 |

| Stressors | −.11 | .41 | −.03 |

| Negative emotions valuable × Stress | 2.43* | .75 | .34 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Positive emotions are valuable | .45 | 2.20 | .02 |

| Stressors | .29 | .41 | .08 |

| Positive emotions valuable × Stress | 2.36* | .83 | .31 |

| Model 3 | |||

| Emotions are dangerous | −1.70 | .93 | −.20 |

| Stressors | .15 | .42 | .04 |

| Emotions dangerous × Stress | −.55 | .73 | −.08 |

| Model 4 | |||

| Emotions are just part of life | 2.16* | 1.00 | .24 |

| Stressors | −.39 | .44 | −.10 |

| Emotions part of life × Stress | 2.23* | .96 | .27 |

p < .05

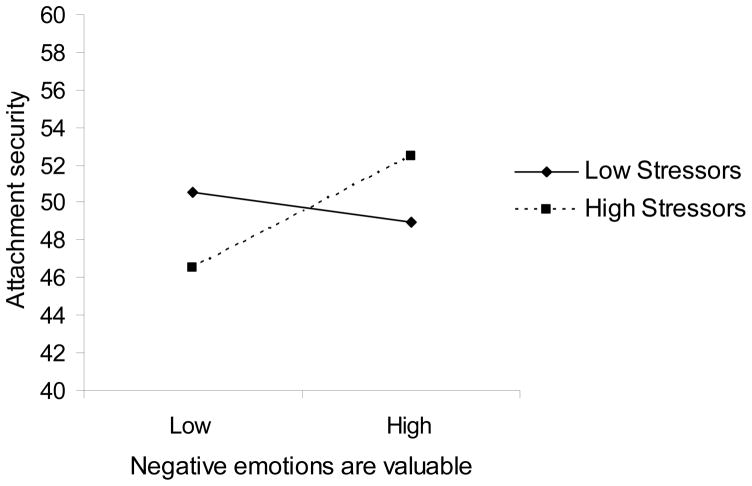

Moderating effects were significant, with stress moderating three of the four relationships between parental beliefs and children’s feelings of security. First, the relationship between the belief that children’s negative emotions are valuable and children’s attachment security was moderated by parental stress, F(3, 83) = 4.03, p < .05. The model explained 13% percent of the variance in children’s attachment security. To visualize the significant interaction effects, simple regression lines were plotted for low (−1 SD), and high (+1 SD) values of the moderator, parental stress; please see Figure 1. For parents reporting more stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that negative emotions are valuable was associated with children’s greater sense of security, B = 3.23, SE = 1.04, t(83) = 3.12, p < .05. In contrast, for parents reporting less stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that negative emotions are valuable was not significantly associated with children’s security, B = −1.63, SE = 1.05, t(83) = −1.56, p > .05. Thus, in situations in which there is more stress, children’s experience of security in the parent-child relationship is greater when parents believe negative emotions are valuable, compared to when parents don’t value negative emotions.

Figure 1.

Relationship of parental belief that negative emotions are valuable with child attachment security at low and high levels of parents’ reported stress.

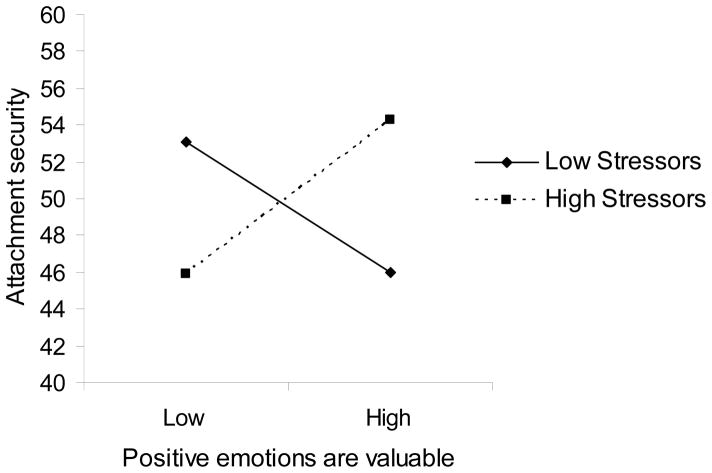

Second, the relationship between the parental belief that children’s positive emotions are valuable and children’s attachment security was moderated by parental stress, F(3, 83) = 2.81, p < .05. The model explained 9% percent of the variance in children’s attachment security. To visualize the significant interaction effects, simple regression lines were plotted for low (−1 SD), and high (+1 SD) values of the moderator, parental stress; please see Figure 2. For parents reporting more stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that positive emotions are valuable was associated with children’s greater sense of security, B = 2.84, SE = 1.22, t(83) = 2.32, p < .05. In contrast, for parents reporting less stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that positive emotions are valuable was associated with children’s lower sense of security, B = −2.53, SE = .99, t(83) = −2.54, p < .05. Thus, for those parents reporting more stress, the more they believe that positive emotions are valuable, the more security their children experience in the parent-child relationship. Conversely, for those parents reporting less stress, the less they believe that positive emotions are valuable, the more security their children experience in the parent-child relationship.3

Figure 2.

Relationship of parental belief that positive emotions are valuable with child attachment security at low and high levels of parents’ reported stress.

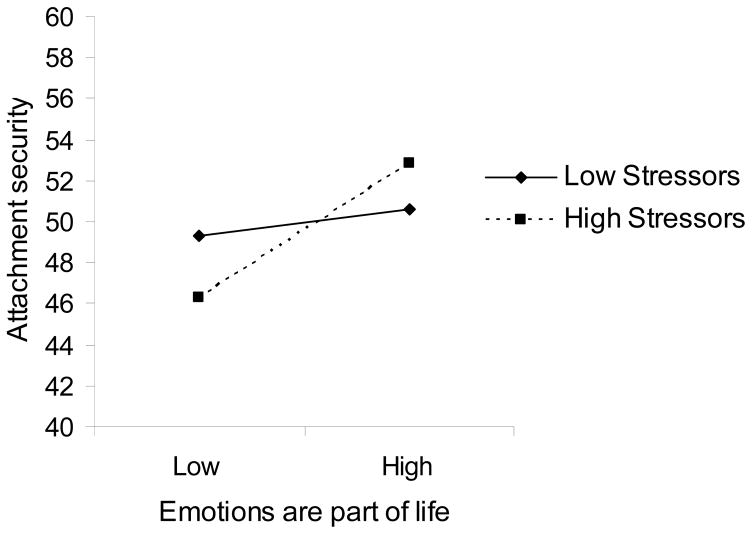

Third, the relationship between the parental belief that children’s emotions are just a part of life and children’s attachment security was moderated by parental stress, F(3, 83) = 2.34, p < .05. The model accounted for 8% percent of the variance in children’s attachment security. To visualize the significant interaction effects, simple regression lines were plotted for low (−1 SD), and high (+1 SD) values of the moderator, parental stress; please see Figure 3. For parents reporting more stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that emotions are just a part of life was associated with children’s greater sense of security B = 3.29, SE = 1.27, t(83) = 2.59, p < .05. In contrast, for parents reporting less stress in the past 24 hours, their belief that emotions are just a part of life was not significantly associated with children’s sense of security B = −.40, SE = 1.14, t(83) = −.35, p > .05. Thus, in situations in which there is more stress, children’s experience of security in the parent-child relationship is greater when parents believe emotions are just a part of life.

Figure 3.

Relationship of parental belief that emotions are part of life with child attachment security at low and high levels of parents’ reported stress.

Finally, the model with the parental belief that children’s emotions are dangerous was not significant, R2 = .05, F(3, 83) = 1.45, p > .05.4

Discussion

Our study explored how four types of parental beliefs about children’s emotions and parents’ experience of daily stress relate to children’s feelings of security in the parent-child relationship in middle childhood. We had predicted both individual and joint associations of parental beliefs and parental experience of stress with children’s attachment security. We found some limited support for a relationship between parental beliefs and children’s attachment security. Most interesting, however, was the consistent evidence suggesting an interplay between parental beliefs and stress when predicting children’s attachment security. Specifically, parental stress moderated the relationship between three of the four parental beliefs about children’s emotions and children’s attachment security. Within the context of high parental stress, children reported greater security in the parent-child relationship when their parents had stronger beliefs about the value of children’s negative emotions, the value of children’s positive emotions, and the nature of children’s emotions as a part of life. When parents were not experiencing much stress in their daily lives, children’s attachment security was largely unrelated to parental beliefs about children’s emotions, with the one exception we address next.

The unexpected negative relationship between parental beliefs about the value of children’s positive emotions and children’s attachment security when parents were not stressed was not consistent with the pattern of findings for the other beliefs about emotions, and leaves us to consider what about positive emotions beliefs could be problematic during times of low stress. It may be that strong encouragement of children’s positivity during non-stressful, typical day-today situations is perceived by children as somewhat intrusive or forcing a “too happy” view of things; in contrast, parents who do not value positive emotions may put less pressure on children to express positive emotions when they are not necessarily experiencing them. Another possibility is that children are driving this effect.5 For example, it could be that children who express both low positive affect and an insecure attachment in less stressful circumstances may elicit parental beliefs that place greater value on positive emotions, as they do not observe these behaviors frequently in their child. This association is more likely for parental beliefs about the value of positive emotions than for the other beliefs; nevertheless, replication would be needed to establish confidence in this particular effect.

As noted above, there was some evidence for an overall positive relationship between the parental belief that children’s emotions are just a part of life and children’s attachment security. That this effect emerged in the regressions but not the correlational analyses suggests the possibility of a suppression effect. That is, parental stress may be suppressing the relationship between the parental belief that emotions are just a part of life and children’s attachment security, which then emerges when parental stress is controlled in the regression. The lack of support for the other direct relationships, however, suggests that it is the combined conditions of value beliefs and high stress which are associated with children’s perceptions of the parent-child relationship.

Decades of theorizing and research support the importance of parents’ emotion-related responsiveness in the development of a secure attachment (Bowlby, 1980; Bretherton, 1985; 1990; Cassidy, 1994). The stress literature provides evidence for a spillover effect in which parental stress from different sources outside of the parent-child relationship affects child outcomes (e.g. Dunn, O’Connor, & Cheng, 2005; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Gerard, Krishnakumar, Buehler, 2006; Katz & Gottman, 1996) including the parent-child attachment relationship (Coyl et al., 2002). The present findings make the additional contribution that when life is going well and is relatively stress-free for parents, their beliefs about children’s emotions have little impact on children’s feelings of security with their parents. However, when parents are experiencing high levels of stress, parental beliefs that accept and value children’s emotions are associated with children’s greater security in the parent-child relationship. It may be that parental beliefs that value children’s emotions direct the degree to which they are accepting of and responsive to children’s emotions; which in turn influences children’s perceptions of the parent-child relationship.

Evidence is already accumulating to suggest that parental behavior is the potential mechanism for the communication of these beliefs, including links between parental beliefs and supportive behaviors (Wong et al., 2008; 2009), and between supportive behaviors and children’s attachment security (Bretherton, 1985). Now that the relationship between beliefs and children’s attachment has been established, within the context of parental stress, the next step might be to include a variety of parental behaviors in addition to beliefs, in order to test whether parents who are or are not under stress differentially express their beliefs through various behaviors. Future research might assess whether parents who accept or value negative emotions in children are also more accepting of their own negative emotional experiences, and whether parents who cope better with their own feelings during stress generate different sets of emotion socialization behaviors with their children. In addition, children’s temperament and cultural contexts may moderate these processes.

Due to the concurrent, correlational nature of the data in the current study, there are several alternative explanations for the effects in the current study. We have interpreted the interaction effects as indicating that stress moderates the relationships between parental beliefs and children’s reports of their attachment security. It is also possible that parental beliefs are the moderators, which then clarify the relationship between parental stress and children’s attachment security. This interpretation would suggest that when parents do not value children’s emotions, their stress has greater impact on children’s feeling of security, with greater stress decreasing children’s feelings of security. When parents value children’s emotions, however, their stress fails to alter children’s feelings about them, perhaps because of the support the children feel regarding their own emotional lives. Research including children’s reports of stress as well as parents’ would help provide support for this more complicated, but plausible, alternative interpretation. Finally, these findings could be interpreted as suggesting that children’s perceived attachment security influences parental beliefs about children’s emotions and parental stress. For example, when children are less secure in the parent-child relationship, parents may also feel less secure in the relationship and as a result, report experiencing more stress and less value for children’s emotions. Research assessing parental reports of security in their relationship with their children and over time might help assess the likelihood of such bidirectional possibilities.

One strength of the current study was the inclusion of parents and children from two ethnic minority populations: African Americans and Lumbee American Indians. Participants from these two groups were especially invited in answer to the call for more cultural diversity in the study of psychology (Hall & Maramba, 2001; Sue, 1999). We did not expect any differences as a result of ethnic status, nor did we find any, in our small sample. It should be noted however, as is the case with research including primarily European-American families, caution should be exercised in generalizing conclusions to other samples pending replication of these findings.

The current study extends previous work on understanding the parent-child attachment relationship in middle childhood and illustrates the importance of parental beliefs about children’s emotions for children’s attachment security. Results from the current study suggest that when parents are experiencing stress, their beliefs valuing children’s emotions may provide a buffer that protects or enhances children’s feelings of attachment security, thus contributing to children’s feelings of attachment security with their parents.

Footnotes

The Lumbee have achieved state recognition as American Indians, and seek official status at the federal level. A tight-knit, family- and community- focused population, the Lumbee remain relatively unassimilated with other ethnic groups. Religion, family, and getting along with others are highly valued, and interactions between parents and children are marked by very respectful exchanges (Parker et al., 2010). The majority of the 50,000 Lumbee in the United States live around the small town of Pembroke, North Carolina.

When the data were reanalyzed without the four parents who reported the day was not at all typical, all tests of the hypotheses were highly similar to what we report for the full sample.

Because of the negative skew, scores for the belief that positive emotions are valuable were log transformed and reanalyzed. All effects were highly similar to those reported above.

Although no cultural differences were hypothesized, we had enough participants in two cultural groups (African American and Lumbee American) to assess whether variations appeared in the above patterns. Five of the six intracorrelations within parent beliefs were similar across ethnicity. The correlations between emotions are dangerous and positive emotions are valuable, however, were not equivalent across ethnicities, z = 2.06, p < .05. Although neither correlation was significantly different from zero, the relationship was positive for the African American parents and negative for the Lumbee parents.

The four moderation models were also tested within each ethnicity and two of the eight moderation models maintained significance despite dividing the sample in half; in all cases, the interaction was in the same direction as in the combined sample. Nevertheless caution in generalizing these findings to other populations is appropriate.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this hypothesis.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979;34:932–937. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Land D. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. Attachment in adolescence; pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Porter MR, McFarland FC, McElhaney KB, Marsh PA. The relation of attachment security to adolescents’ paternal and peer relationships, depression and externalizing behavior. Child Development. 2007;78:1222–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Chandler AL. Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent-child dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:49–61. doi: 10.2307/353882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The daily inventory of stressful events: An interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9:41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102009001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:3–35. doi: 10.2307/3333824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Communication patterns, internal working models, and the intergenerational transmission of attachment relationships. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:237–252. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(199023)11:3<237::AID-IMHJ2280110306>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:228–283. doi: 10.2307/1166148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyl D, Roggman L, Newland L. Stress, maternal depression, and negative mother-infant interactions in relation to infant attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:145–163. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff M, van IJzendoorn M. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. doi: 10.2307/1132107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ML, Isabella RA, Behunin MG, Wong MS. Attachment to mothers and fathers during middle childhood: Associations with child gender, grade, and competence. Social Development. 2008;17:84–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00416.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, O’Connor TG, Cheng H. Children’s responses to conflict between their different parents: Mothers, stepfathers, nonresident fathers, and nonresident stepmothers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:223–234. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Halberstadt AG. The communication of emotion: Current research from diverse perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. How does family emotional expressiveness affect children’s schemas? pp. 45–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Her P, Halberstadt AG, Perez-Rivera MB. Parents’ beliefs about emotions and children’s recognition of parents’ emotions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2009;30:121–140. doi: 10.1007/s10919-008-0066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Karn MA. Mothers’ beliefs about feelings and children’s emotional understanding. Early Education and Development. 2001;12:117–138. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1201_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Karn MA. The influence of peer relationships and maternal socialization on kindergartners’ developing emotion knowledge. Early Education and Development. 2004;15:39–56. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1501_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J. Impact of chronic and acute stressors on daily reports of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:907–918. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MT, Heinen BA, Langkamer KL. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:57–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Marital conflict, parent-child relationship, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:951–975. doi: 10.1177/0192513X05286020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:243–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D, Mayseless O. Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:530–541. doi: 10.1080/01650250042000366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim-Larson J, Parker AE, Lee C, Goodwin J, Voelker S. Parental meta-emotion and psychometric properties of the parenting styles self-test. Early Education and Development. 2006;17:229–251. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1702_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Dunsmore JC, Thompson JA, Beale KR, Parker AE, Bryant A., Jr Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Emotions. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0033695. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Thompson JA, Parker AE, Dunsmore JC. Parents’ emotion-related beliefs and behaviours in relation to children’s coping with the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks. Infant and Child Development. 2008;17:557–580. doi: 10.1002/icd.569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Maramba GG. In search of cultural diversity: Recent literature in cross-cultural and ethnic minority psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:12–26. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of self: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Oxford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 57–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Klepac L, Cole A. Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:457–466. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Richardson RA, editors. Attachment in middle childhood. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Tomich PL, Aspelmeier JE, Contreras JM. Attachment-based assessments of parent-child relationships in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:614–626. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Tomich PL, Kim P. Normative trends in children’s perceptions of availability and utilization of attachment figures in middle childhood. Social Development. 2006;15:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467–9507.2006.00327.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laible D. Maternal emotional expressiveness and attachment security: Links to representations of relationships and social behavior. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:645–670. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2006.0035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth-LaForce C. Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:247–255. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid N, Bigelow AE, McLaughlin J, MacLean K. Maternal mental state language and preschool children’s attachment security: Relation to children’s mental state language and expressions of emotional understanding. Social Development. 2008;17:61–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Guthrie IK. Consistency and change in children’s emotionality and regulation: A longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:413–444. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J, O’Brien M, Blankson A, Calkins S, Keane S. Family stress and parental responses to children’s negative emotions: Tests of the spillover, crossover, and compensatory hypotheses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:671–679. doi: 10.1037/a0015977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Almeida DM, Charles ST. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. Journals of Gerontology. 2007;62:216–225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Mroczek DK, Spiro A. Neuroticism moderates the daily relation between stressors and memory failures. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:287–296. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, McDowell DJ. Toward and expanded model of emotion socialization: New people, new pathways. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:303–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AE, Halberstadt AG, Dunsmore JC, Townley GE, Bryant A, Jr, Beale KS, Thompson JA. “Emotions are a window into one’s heart”: The qualitative analysis of parental beliefs about children’s emotions across three ethnic groups. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2012.00676.x. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza JR, Charles ST, Almeida DM. Living with chronic health conditions: Age differences in affective well-being. Journals of Gerontology. 2007;62:313–321. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Wood J. Effects of daily stress at work on mothers’ interactions with preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:900–108. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.1.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. The development of emotional competence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Serido J, Almeida DM, Wethington E. Chronic stressors and daily hassles: Unique and interactive relationships with psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:17–33. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Science, ethnicity, and bias: Where have we gone wrong? American Psychologist. 1999;54:1070–1077. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins SS. Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol. I. The positive affects. Oxford England: Springer; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins SS. Affect imagery consciousness, 2: The negative affects. New York, NY US: Tavistock/Routledge; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Wong MS, Diener ML, Isabella RA. Parents’ emotion related beliefs and behaviors and child grade: Associations with children’s perceptions of peer competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MS, McElwain N, Halberstadt AG. Parent, family, and child characteristics as predictors of mother- and father-reported emotion socialization practices. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:452–463. doi: 10.1037/a0015552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]