Abstract

William Henry Welch's selection in 1884 as the first faculty member of the new medical school at Johns Hopkins created the invigorating atmosphere that generated the revolutionary changes in medical training and laboratory medicine that transformed medicine in America. Dr. Welch's family traditions, his New England upbringing, Yale education, and German university experience prepared a unique individual to lead American medicine into the 20th century.

“In addition to a three-story intellect Welch has an attic on top.” —William Osler (1)

On April 8, 1930, a special tribute was held in Washington, DC, to celebrate the 80th birthday and honor the achievements of William Henry Welch. No physician before or after Dr. Welch has been recognized so widely or honored in such an extraordinary manner. Sixteen hundred of his friends and associates assembled with President Herbert Hoover. The event was disseminated around the country and the world by radio broadcast. Additional celebrations occurred in Norfolk, Connecticut, Dr. Welch's birthplace; Yale University, his alma mater; Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he had graduated from medical school; the Rockefeller Institute; Princeton University; the University of Pennsylvania; Western Reserve University; Vanderbilt University; Minnesota University; and Stanford University. Further celebrations were held by the American Social Hygiene Association in New York City, Portland, Oregon, and Cleveland, Ohio. Around the world, celebrants gathered at the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland; the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France; the London School of Hygiene in London, England; the Peiping Union Medical College in Beijing, China; the Kitasato Institute in Tokyo, Japan; the Robert Koch Prussian Institute in Berlin, Germany; and medical society meetings in Leipzig, Copenhagen, and Dublin. A special portrait was painted for the occasion, and copies were presented to the organizations that participated; this portrait graced the cover of the April 14, 1930, issue of Time (Figure 1) (2).

Figure 1.

Time cover, April 14, 1930. Reprinted with permission from the Alan Mason Chesney Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Welch acknowledged that his success had much to do with the advances in education, technology, and science that were transforming society at the end of the 19th century (3). It was a propitious time to initiate changes in medicine. In the United States, medical education and medical practice had experienced a century-long slide characterized by unprofessional and inadequate training programs, the absence of any laboratory teaching or scientific investigation, a lack of certification or training requirements, and the widespread use of quackery in the practice of medicine. Accomplished men had tried to implement change, but it was the work of Welch at Johns Hopkins that began an era of biological investigation and quality medical education that created an improvement in the standards of practice in the United States that has been sustained for over 100 years (4).

Welch's character was forged by his unique family and its New England traditions. He was the descendant of an Irish refugee and from a family of three generations of prominent physicians and community leaders. This essay describes his ancestors, his childhood, his education at Yale College and Columbia Physicians and Surgeons medical school, and his experiences in Germany, where medical laboratories served as a model for biological research that Welch initiated in New York and applied at the Johns Hopkins University.

ANCESTORS

Oliver Cromwell's soldiers, in a rampage across Ireland, drove two thirds of the Irish from their homes. In 1636, William Welch's ancestor Philip Welch, an 11-year-old boy, was kidnapped and sold into servitude to Samuel Symonds, the governor of Massachusetts. Philip escaped after 3 years, refusing to work without pay for the usual 7 years. Philip's great-grandson was Hopestill Welch. Hopestill served in the French and Indian Wars under General Putram and as a soldier in the Continental Army under Benedict Arnold. Pensioned as a sergeant, he retired to Norfolk, Connecticut, about 1772 (5).

Hopestill had 3 sons and 10 daughters. His son Benjamin was born in Windsor, Connecticut, in 1767 and moved with the family to Norfolk. There Benjamin was placed in apprenticeship with Dr. Ephraim Guiteau. He was a founder of the county medical association, was the first physician resident in the town, and was widely respected, with a large and successful practice (6). Benjamin apprenticed in Dr. Guiteau's home until he was 21 years old and was granted a medical degree by the county medical association in 1788. Benjamin had eight children; the three sons all became physicians. A man of substantial energy, he was active in the church and community. During his life, he held almost every elected office in the town, establishing a leadership tradition that was continued with his son and grandson. His eulogy described him as “a man and a physician [who] possessed and exhibited all those qualities that inspire confidence and win regard” (7).

William Wickham Welch, the son of Benjamin and the father of William Henry, was born in 1818. William Wickham apprenticed briefly with his older brother Benjamin before entering the Yale Medical Institution, from which he graduated in 1839.

In 1843, on a visit to Hillsdale, New York, he was introduced to his future wife, Emeline Collin. Emeline traced her ancestry to Huguenot exiles who fled from France to Rhode Island in 1695. A fanciful young woman, she enjoyed writing and often depicted herself as secluded, intellectual, and observing of life rather than actively partaking in its pleasures. William Wickham was enchanted by Emeline and followed the initial visit with a request for a ride in the countryside, where without hesitation he proposed marriage. Alleging a busy practice, he sustained the relationship by mail and returned to Hillsdale only after she had accepted his proposal for marriage.

Emeline bore two children: a daughter, Emeline Alice, born May 13, 1847, and a son, William Henry, born April 8, 1850. In 1846, she developed a serious illness from which she never recovered completely. Following William's birth, a serious decline in her health led to her death on October 29, 1850, when William was only 6 months old (8).

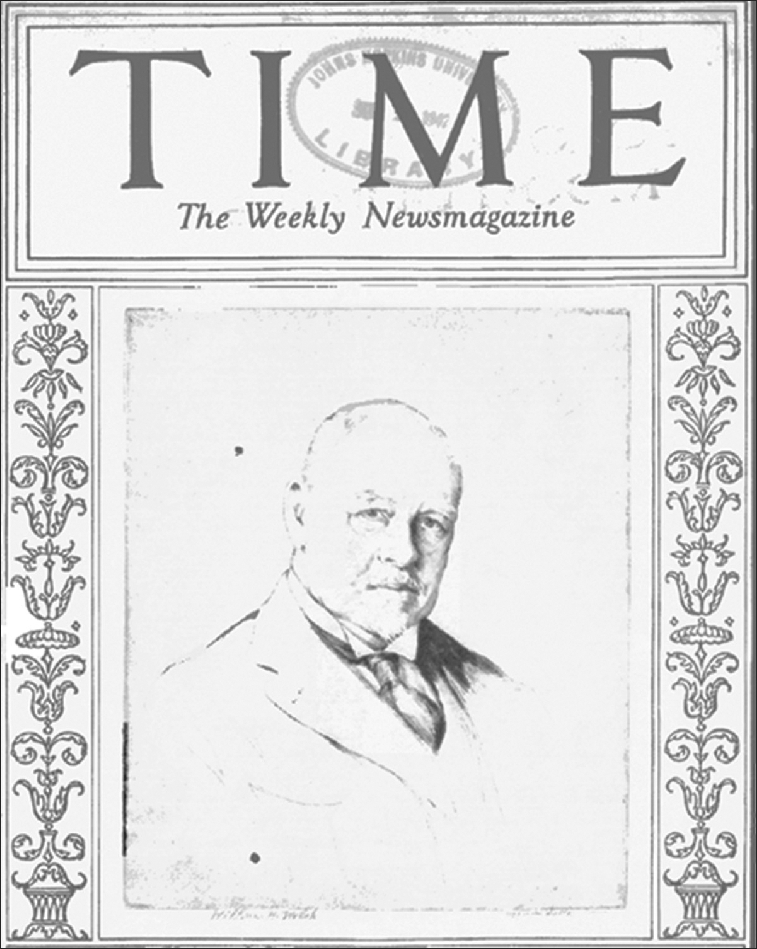

William Wickham placed his daughter with her mother's aunt in Winchester Center, a community 6 miles from Norfolk. The responsibility for running the house and raising his son was given to his mother, Elizabeth, a deeply religious woman, active in the church and known in the community by the endearment “Grandma Welch.” Her relationship to her grandson was a pious combination of benevolence, austerity, and affection. It seems that young Welch grew up with an absentee father and an attentive, caring but sober, spiritual, and fastidious grandmother. He was close with his sister who in later years often served as a confidant and advisor (Figure 2). His playmates were his many cousins who lived in close proximity to his father's home (8).

Figure 2.

Standing on the porch of William Wickham Welch's home and office, from left to right: Frederic Walcott, his brother-in-law; William Henry Welch; Emily Sedwick Welch, his stepmother; William Wickham Welch, his father; and Emeline Walcott, his sister. Seated are the Walcott children. Reprinted with permission from the Norfolk Historical Museum.

William Wickham Welch represented the town in the General Assembly from 1848 to 1881, was a state senator in 1851, and served in the US Congress from 1855 to 1857 (9). At his funeral, Dr. Hiram Eddy said:

Never have I known a physician whose presence in the sickroom was so sweet and encouraging a benediction. He had a sympathetic courage for his patient, and the patient caught it like a contagion. The warm, sincere and cheerful feeling for his patient was an anodyne which helped his prescriptions. His goodness had a healing power. His touch when examining the pulse and diagnosing the disease, was a professional touch indeed; but it was more; it was a touch of kindness; you loved to have him feel your pulse and the pulse itself felt a sort of thrill, and wanted to be as he would like to have it. While his quiet and unostentatious sympathy, one of the powers of the ideal physician, was conspicuous in Dr. Welch, still this warm sentiment was connected with a profound skill that called him in council and practice, over the State and out of it (10).

This benediction clearly describes the special character of the Welch family.

CHILDHOOD

Welch recalled his childhood education:

The educational advantages were good for that time and the intellectual and interests were not lacking. There was a small circulating library and as we grew in years there was much reading of books. It was a time when everyone was reading the same books, fewer in number but more intensively perused than today. It might be Dickens, or Scott, or Harriet Beecher Stowe, or even Jane Eyre, Rutledge, or Beulah Dred or Wide, Wide World to say nothing of the Scottish Chiefs and Thaddeus of Warsaw. We exchanged books and we talked about them.

The outlook upon life may have been narrow but upon the small altars the fire burned brightly. Our patriotism was stimulated by the Fourth of July celebrations and orations and especially by the events of the civil war. The days of the old Lyceum lectures had not passed.

As in many New England towns characters of strong individuality sometimes even of marked personal idiosyncrasy were developed. The religious faith which had come down from the fathers of the New England Commonwealths was still strong and the life of the church and of the town meeting was vigorous. The social atmosphere was that of genuine democracy of mutual interest of mutual helpfulness and kindliness, strikingly exemplified (11).

Welch commented on the special character of New England life that was important to his own success. At the unveiling of a tablet in memory of Miss Isabella Eldridge, a prominent patroness of Norfolk, he said:

In the middle of the last century, the New England towns, and none more so than this beautiful town of Norfolk, afforded the best which this country could offer in the way of heredity and environment for the up building of that strength of character, that soundness of mind and of body, those moral and intellectual ideals which have been in the past (whatever the future may have in store for us), the determining forces in the development and prosperity of our country and happy they whose lot was here cast.

Our life's as children centered around the family, the church, the Sunday school, the walks to the cemetery on Sunday afternoon, the school, the village green, our games, our picnics in the old spring lot, our birthday parties. I was led to believe by my father, and I do not dispute it, that I owed every thing in my start in life to my attendance at the Misses Nettleton's school, and I am sure that it was an excellent school of its kind.

The Norfolk of those and later days bore no resemblance to the “Main Street” depicted so realistically in that most depressing book by Sinclair, in these beautiful surroundings there resulted a life and work of sincere grace (11).

The Welch family chronicles described a family fully integrated in its community. Welch's life was rich in love and affection and mentored by family members with a deep commitment to each other, their profession, and their church. It was an intellectual environment with an emphasis on learning and reading. Harvey Cushing described the family in his eulogy to Welch:

So it would seem there must have been at least ten doctors in three generations, all apparently men of very similar type, good judges of people and good public servants, men able to instill confidence and win regard, all of them blessed with a rare capacity to gain and retain friendships with young and old, all of them apparently men who were respected, admired and beloved (12).

The characteristics so evident in his later life—an agreeable personality, engaging conversation, elegant manners, and an extraordinary mind, full of energy—were forged during this time.

EDUCATION

In 1866, Welch entered Yale College. He was an ardent, intense, proud individual, secure in his intellect and spiritually devout. Yale at this time was a parochial school. The college had only eight full professors, a classical curriculum, and the entire 4 years consisted of required courses. The academic departments consisted of natural philosophy, astronomy, moral philosophy, metaphysics, rhetoric, English literature, geology and mineralogy, Latin and Greek language and literature, history, and mathematics. The sciences were not included in the curriculum.

Those Yale years are revealed in a letter to Welch from his classmate, Professor E. S. Dana, who wrote:

My thoughts go back to our years of 1866 to 1870, and I am much impressed at the complete change in the intellectual side of the life at Yale. Do you recall “Pill” Otis, who was our Sophomore Latin tutor? Also “Nancy” Smith, who commenced Natural Philosophy (Olmstead's) with us in junior year by telling us frankly that he was not familiar with the subject but would make it as interesting as possible…. Sumner began with us in Geometry and was one of the few who appreciated the difference between teaching and hearing the boys recite all that dear old Loomis (the professor of natural philosophy and astronomy) wanted was to hear again the exact words in his book—“not a superfluous word in the book” was his motto…. Certainly we lived through a strangely stagnant time in Yale's history (13).

The design of the program at Yale was narrow and the teaching less than dynamic. Welch felt personally that his election to the secretive senior honorary society Skull and Bones was the most important event that occurred for him at Yale. Welch wrote to his nephew that any number of places would do for the man who could not make Bones, but only Yale for the man who could. This secret society's membership included some of Yale's most famous and influential graduates. Skull and Bones membership was determined by scholarship, social position, popularity, and leadership skills. Its members were influential with the administration of Yale, and it was rumored that Bones was involved in the business of the college, sitting in judgment of instructors and curriculum (14). This was Welch's first opportunity to participate in the politics and organization of the university, an experience he seems to have relished. It is of interest to note that Daniel Coit Gilman, the future president of Johns Hopkins University, was a Bones man and still at Yale associated with the Sheffield Scientific School when Welch was a student. Although there is no record of their acquaintance prior to Welch's interview at Johns Hopkins, it is likely they had contact given the reputation for alumni to remain active in the organization.

Welch had hoped to stay at Yale as an instructor in the classics department, but the desired position never materialized. He reluctantly accepted a position at a new preparatory school for girls in Norwich, New York, where he found the task of teaching young ladies the classics both boring and monotonous. The school failed after its first year, and he was left without a position or an inclination to continue in teaching (15).

A gifted scholar, but not a talented or passionate teacher, he was unable to find a place for himself at the college. Yale and Bones had aroused an enthusiasm for organization, policy, and supervision. He returned to his family for advice. His father had long been encouraging him to enter medicine with the hope he would join him in Norfolk; now his stepmother and sister, who were his confidants and advisers, encouraged him to consider medicine.

Welch chose not to go directly to medical school but to first improve his scientific training by entering the Sheffield Scientific School in New Haven. The school, associated with Yale, had excellent laboratories, and its chemistry laboratories were superior to those of any medical school in the country. The faculty of the school included respected scientists Oscar Allen and George Fredrick Barker, professors who taught hands-on experiments in the laboratory (16).

In the fall of 1872, Welch entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. He was soon immersed in and committed to his medical studies. Although the College of Physicians and Surgeons was one of the oldest and most respected medical schools in the country, it was, like all American medical schools, proprietary and without scientific laboratories or entrance requirements for the students. Only 2 years, which consisted of two 6-month terms, were required for graduation. The students bought tickets for the entire term of lectures and attended in any order that appealed to them. The third year of training involved an apprentice with a physician associated with the medical school. The only exam was the final, which Welch described as the easiest test he had ever taken. The professors were paid entirely from the tuition of the students, which served as a strong incentive not to fail many in the class. Reflecting on the school, Welch commented:

One can decry the system in those days, but the results were better than the system. The College of Physicians and Surgeons stood then, as it has always stood, in the front rank of American medical schools. Our teachers were men of fine character, devoted to the duties of their chairs, they inspired us with enthusiasm, interest in our studies and hard work, and they imparted to us sound traditions of our profession; nor did they send us forth so utterly ignorant and unfitted for professional work as those born of the present, greatly improved methods of training and opportunities for practical study are sometimes wont to suppose (3).

During medical school, Welch's one opportunity for hands-on laboratory experience and respite from the lecture hall was in the anatomy dissecting room. There his knowledge was extended with direct observation, and he became passionately interested in pathological anatomy. He developed a close relationship with his teacher, Francis Delafield, who provided a course in pathological anatomy, an elective that emphasized the findings at autopsy as an important source of medical knowledge. Delafield appointed Welch curator of the Wood Museum of Pathological Specimens, a position that required Welch to supervise postmortem examinations and record the findings. Delafield was an expert microscopist and spent considerable time studying diseased organs through the instrument. Welch, who had won a Varick microscope from his neurology professor, Edward Seguin, for the best essay on his course, could only gaze at the instrument longingly, as there were no courses on using the instrument and professors like Delafield did not offer assistance or training (17).

STUDY IN GERMANY

Welch had another professor in New York whom he greatly admired and visited occasionally at his home, Abraham Jacobi. He was a leading figure in American medicine at the end of the 19th century and advised Welch to seek further study in Germany. The tradition of studying abroad had developed from America's earliest leaders in medicine. American medical students went first to Edinburgh, then to Paris, and then to Germany, with its new university-affiliated laboratory science medical schools. These schools had become the leading centers for scientific investigation and the newly evolving application of the biological sciences to medicine.

In March 1875, Welch wrote his father seeking support for a year of further study in Germany. The senior Welch was not enthusiastic, and Welch responded to his father: “If by absorbing a little German lore I can get a little start on a few thousand rivals and thereby reduce my competition to a few hundred more or less, it is a good point to tally” (18).

Welch sailed for Europe on April 19, 1876. He chose Strassburg, possibly on the advice of Jacobi, or encouraged by several of the medical school faculty who had trained there. The area had recently been acquired by Germany after the Franco-Prussian conflict. Germany was attempting to extend its influence in the area by developing the university into a great center of learning. In Strassburg, Welch found Carl Waldeyer, the renowned anatomist; the pathologist von Recklinghausen, one of Virchow's most famous pupils; and Hoppe-Seyler in physiologic chemistry, one of the founders of this field of study. Welch had hoped to study with von Recklinghausen, but as he had no microscopy skills he had to begin in histology with Waldeyer. He was fascinated and excited with his introduction to German laboratory science. However, he knew he must develop skills for clinical practice and left for Leipzig in August 1876. There he hoped to study neurology with Johann Heubner. He had to change his plans when he found that Heubner was no longer teaching neurology and had turned his attention to pediatrics. This circumstance was most serendipitous for Welch, who chose to work with Carl Ludwig, the foremost experimental physiologist in the world, a committed scientist and medical investigator (19). His outstanding laboratory and method of scientific investigation made an irrevocable impression on Welch, who wrote his father:

My work with Prof. Ludwig has been very profitable, especially in giving me an insight into the apparatus and methods of modern physiology, which is by far the most exact of any of the branches of medicine, this position of exactness having been obtained more through the effort of Prof. Ludwig than any living man. I hope I have learned from Prof. Ludwig's precept and practice that most important lesson for a microscopist, as well as for every man of science, not to be satisfied with loose thinking and half proofs, not to speculate and theorize but to observe closely and carefully facts (20).

Carl Ludwig advised Welch to visit Breslau where his former pupil, Julius Cohnheim, had developed a laboratory of experimental pathology. Welch described the school, the professors, and the significance of the experience in a letter to his father, written shortly after his arrival. He commented:

Prof. Cohnheim and Prof. Wagner are in some respects the antipodes of each other. Wagner has perhaps a greater array of facts at his disposal … has gone deeper into the microscopic details of a pathological change, but while Wagner is often satisfied with the possession of a bare fact, Cohnheim's interest centers on the explanation of the fact. It is not enough for him to know that congestion of the kidney follows heart disease or that hypertrophy of the heart follows contraction of the kidney, or that atheroma occurs in old age, he is constantly inquiring why does it occur under these circumstances. The result is that Cohnheim has taken for his especial studies such common subjects as inflammation, dropsy, embolism and through his investigation these have become perhaps the only subjects in pathology in which our knowledge approaches exactness what is known concerning a physical or chemical process. Pathology and even practical medicine have entered upon a new era since Cohnheim's discoveries in the process of inflammation for there is hardly a disease of which our conception is thereby modified. He is almost the founder and certainly the chief representative of the so-called experimental or physiological school of pathology. That is, he occupies himself with the study of the diseased processes induced artificially on animals (21).

Cohnheim frequently invited the students to dinners that often included prominent German jurists, intellectuals, and visiting scientists. The permanent Cohnheim circle included the philosophy professor Dilthey, the jurists Gieke and von Bar, and the national economist Luigi Brentano. Welch's fellow student, the famous Danish bacteriologist Carl Julius Salomonsen, described reminiscences of the summer semester of 1877 at Breslau. The article was written for the journal Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift in an issue dedicated to Nobel Laureates Paul Ehrlich and Emil von Behring. Salomonsen commented that Welch was a student in the same laboratory, having just finished 8 months under Ludwig. They worked on experiments directly proposed and directed by Cohnheim. They attended lectures and demonstrations and visited the clinics in addition to their experiments. Salomonsen described the day as beginning very early, with breakfast in the many “gardens,” which were divided into beer, coffee, and milk gardens. They arrived at work by 7:00 AM and worked the entire day, returning to the laboratory after dinner and staying until 7:00 or 8:00 PM. It is during this period that Welch completed important studies on the cause of pulmonary edema. As students, they were encouraged to participate in the sessions of the various medical societies. These sessions often included excursions into the beautiful surrounding countryside. Here they heard presentations by Breslau investigators and enjoyed the opportunity for close personal communication. The Breslau summer was an exposure to the entire depth of the German medical university experience: the meticulous experimental work, the intellectual interaction at every level, and inclusion of the brightest minds in the social, political, and scientific communities (22).

Welch left Breslau on October 26, 1877, for Vienna, which was the center of clinical medicine in Europe. He was still very concerned about preparing for eventual clinical practice in America. Welch's experience there was a disappointment. He enjoyed the culture of Vienna but was not satisfied with the clinical experience. He sailed for America on February 6, 1878, hopeful that he could further his interest in laboratory investigation on his return to New York.

In Germany, Welch's luminous mind, alert, intelligent, and receptive, appreciated the significance of the revolution occurring in medicine and recognized that he was capable of initiating this revolution in America. His restless energy, industrious attitude, and ambition were perfectly suited for creating what no American had yet achieved: laboratory-based science and teaching in American medical schools. He was aware of the plan for the Johns Hopkins Medical School and had interviewed with John Shaw Billings, who was Gilman's representative responsible for the physical and intellectual design of the medical school. Welch returned from Europe committed to scientific investigation; clinical practice was no longer a serious consideration.

EARLY CAREER IN THE UNITED STATES

Welch returned to New York seeking a position that might provide a livelihood and still permit laboratory investigation. Francis Delafield at the College of Physicians and Surgeons offered him an unpaid position as lecturer in pathology. Welch asked instead for the opportunity to initiate a laboratory facility at Physicians and Surgeons. Delafield responded that if he could find any available space in the building, he could use it for a laboratory. Welch searched every office, lecture hall, and storage space but to no avail. He turned to his friend and former classmate at Yale, Frederick Dennis, a wealthy and influential member of New York society. Dennis was associated with Bellevue Medical College, the less prestigious New York school but home to one of the most prominent clinicians in America, Austin Flint Sr. It was at Bellevue after much negotiation that Welch obtained three rooms furnished with kitchen tables. There were no microscopes, instruments, or specimens, and the college had provided only $25 to equip the laboratory. Welch expressed his frustrations in a letter to his sister:

I have been trying to get the laboratory in order so as to organize a class this summer, but the material was so scanty that I should have given up the idea of starting anything there this summer, unless those who wish to have their students work there were not so urgent to have me begin. I can get as many students as there are places for, but I can not make much of a success out of the affair at present. I seem to be thrown entirely upon my own resources for equipping the laboratory and do not think that I can accomplish much.

I some times feel rather blue when I look ahead and see that I am not going to be able to realize my aspirations in life. I may be able to make a support in New York, and even if I should succeed in accordance with the hopes of my friends, it would not be the kind of success which I should like. I am not going to have any opportunity for carrying out as I would like the studies and investigations for which I have a taste. There is no opportunity in this country, and it seems improbable that there ever will be. I can quiz students, I can teach microscopy; and pathology, and perhaps get some practice and make a living after a while, but that is all patchwork and the drudgery of life and what hundreds do. I shall never be independent of these things (23).

Welch persevered and obtained six antique microscopes for his laboratory with slides and dyes for specimens. Since the students had no microscopy experience, specimens obtained from the dead house were not appropriate. Welch, with the assistance of his family and friends, went frog hunting and used live frogs for their first investigations. The first laboratory course at an American medical school began in 1879 and was an immediate success. Students from all three New York medical schools sought admission to the class. The demand placed considerable pressure on the faculty of Physicians and Surgeons to open their own laboratory. Where there had been no space, equipment, or money, new resources were secured and a laboratory was created with Delafield as the director. Welch was offered a position as director of histology with a $500 salary. He was very much attracted to the offer and the financial support, but Flint applied considerable pressure for him to stay at Bellevue, where he had been given his first opportunity.

Welch later commented on his experience in New York with his observations in Germany:

I was often asked in Germany how it is that no scientific work in medicine is done in this country, how it is that many good men who do well in Germany and show evident talent there are never heard of and never do any good work when they come back here. The answer is that there is no opportunity for, no appreciation of, no demand for that kind of work here. In Germany on the other hand every encouragement is held out to young men with taste for science (24).

The Bellevue laboratory produced a paltry income limited to the students' fees and, in order to support himself, Welch was required to lecture students, tutor for tests, maintain an office practice, and serve as assistant to the senior Flint. There was no time for original investigation, but Welch remained focused on his goal to be a research pathologist. When Austin Flint Sr. offered him a full professorship of clinical medicine, he turned it down, persistent in his hope to be a research pathologist.

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

In 1867, Johns Hopkins, a director of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, devoted his fortune to establishing a new university, hospital, and medical school. The founding board of trustees selected Daniel Coit Gilman, who was the president of the University of California, for the purpose of creating a university-affiliated medical school that would set the standard for medical education in America. Gilman then chose John Shaw Billings, formerly of the US Surgeon General's office, to assist in designing the hospital and selecting faculty for the medical school. For this purpose, he had traveled to Europe several times to observe their medical institutions and interview possible candidates, including European professors and Americans training in their laboratories. It was in Germany that Billings first met Welch and discussed a future position at Johns Hopkins (24).

John Shaw Billings finally did interview Welch in New York in 1884, where he observed Welch demonstrate an autopsy in the hospital amphitheatre. He wrote to President Gilman:

I saw Dr Welch, had a long talk with him, heard him lecture and saw him directing work in his laboratory. He is 33 years old, unmarried, of good personal address, modest, quiet, and a gentleman in every sense so far as I can judge. He is a good lecturer, an excellent laboratory teacher, and has a keen desire for an opportunity to make original investigations, being activated I think by the true scientific spirit. He has written little under his own name. He has been trying to make some original investigations in the causes and pathology of Dysentery but has very little time as he has to make his living by students and Doctors fees and must give them the first place. Upon the whole I think he is the best man in this country for the Hopkins (25).

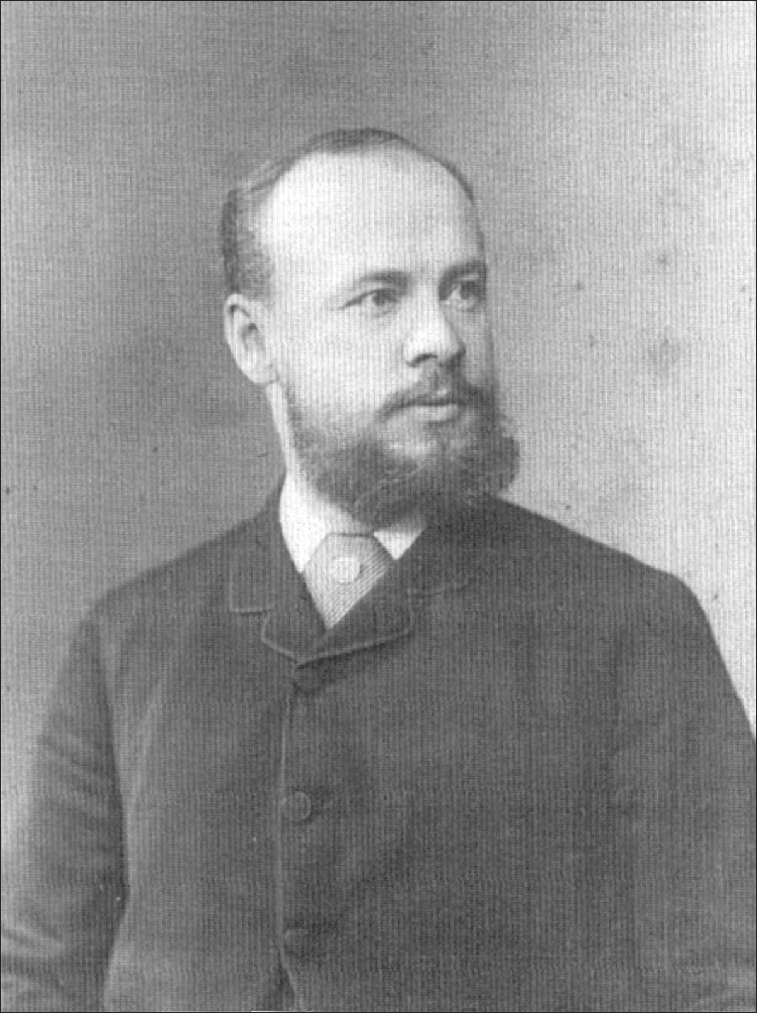

Welch at Johns Hopkins opened new doors for American physician scientists and created a new paradigm for medical education (Figure 3). Welch was the foundation upon which the medical school was built, but it is William Osler who was the most famous representative of the institution. Michael Bliss in his biography of William Osler described Osler's popularity with the students, his contribution to innovative teaching methods, his charismatic personality, the classical and entertaining lectures, and the authoritative textbook—all of which contributed to making Johns Hopkins a very, very good medical school (26). Bliss described Welch as aloof, remote, and reticent. He was considered by some of the students as a poor teacher and lazy, a bon vivant who enjoyed gourmet dining and amusement parks. But this was not the opinion of his contemporaries at Johns Hopkins or the leaders of philanthropic organizations that sought his advice. Alan M. Chesney, dean of Johns Hopkins Medical School, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Welch's birth, described Welch as follows:

Figure 3.

William H. Welch in 1884 after his appointment at Johns Hopkins. Reprinted with permission from the Alan Mason Chesney Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Dr. Welch had a strong hold upon the students and his nickname, “Popsy”, attested to the respect and affection in which he was held by all of them. They could not fail to appreciate the lucidity of his presentations, the breadth of his knowledge of the subject matter under consideration, nor the faculty, which he possessed to an unusual degree, of investing each topic which he discussed with a measure of interest that seemed almost to transcend, at times, the intrinsic value of the subject itself. Indeed, many a time the discussion which Dr. Welch gave of a colleague's paper in the meetings of the Johns Hopkins Medical Society was a clearer and better exposition of the subject than was the paper itself (27).

The attributes that Welch brought to Johns Hopkins were his intellectual brilliance, organizational ability, and judgment in recognizing and advancing talented individuals. These were the contributions so appreciated by Osler, Chesney, Cushing, and Welch's contemporaries. Welch's original desire to pursue research was altered as the medical school became the model to change medicine in America. Unlike Osler, who was always a committed clinician, teacher, and investigator, Welch moved from project to project, leaving behind his interest in laboratory research and teaching students as he went on to create and enhance the institutions, journals, and professional societies that revolutionized medicine in America. If “Popsy” was a nickname of respect and affection by his colleagues, it was also used with ridicule and humor by the students.

He lived a productive 84 years, served as dean of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, adviser to the Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Milbank Foundations, brigadier general in the army, founder of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, and first director of the Johns Hopkins Institute of Medical History. He died on April 30, 1934, and was buried with the Doctors Welch in the church burial grounds in Norfolk, Connecticut.

References

- 1.Riesman D. William Henry Welch, scientist and humanist. Scientific Monthly. 1937;41(3):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeburg V, editor. William Henry Welch at Eighty: A Memorial Record of Celebrations Around the World in His Honor. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund; 1930. pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch WH. Papers and Addresses by William Henry Welch. vol. 3. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press; 1920. The Harvey Lecture: Medical education in the United States. Address delivered before the Harvey Society, New York City, April 20, 1916; pp. 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludmerer KM. Learning to Heal. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1985. The innovative period. chap. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crissey TW. History of Norfolk, Litchfield County, Connecticut 1744–1900. Everett, MA: Massachusetts Publishing Co; 1900. pp. 466–469. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crissey: 470–472.

- 7.Crissey: 481.

- 8.The Lure of the Litchfield Hills – The Great Welch Family of Doctors [magazine], August 1934, pp. 4–27. Available at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Series XIV/A, Folder 163/62.

- 9.Crissey: 475–477.

- 10.Crissey: 468.

- 11.Welch WH. Remarks at the unveiling of a tablet in memory of Miss Isabella Eldridge in the Congregational Church, Norfolk, Conn. Litchfield County Leader, July 1, 1921.

- 12.Cushing H. The Doctors Welch of Norfolk. N Engl J Med. 1934;201:1132–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flexner S, Flexner JT. William Henry Welch and the Heroic Age of American Medicine. New York: Viking Press; 1941. Letter from Dana to Welch, Nov. 5, 1933; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrett WH., 2nd Yale, Skull and Bones, and the beginnings of Johns Hopkins. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2011;24(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2011.11928679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming D, William H. Welch and the Rise of Modern Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flexner and Flexner: 55–56.

- 17.Flexner and Flexner: 64.

- 18.Flexner and Flexner: 76.

- 19.Flexner and Flexner: 79–82.

- 20.Flexner and Flexner: Letter to his father, February 25, 1877: 85.

- 21.Flexner and Flexner: Letter to his father, September 23, 1877: 95.

- 22.Salomonsen CJ. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift. 1914;51(1):485–490. translated by C. Lilian Temkin. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flexner and Flexner: Letter to his sister, April 21, 1878: 112.

- 24.Welch WH. Some of the conditions which have influenced the Development of American Medicine, Especially during the Last Century. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1908;19:33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billing JS. Letter to D.C. Gilman, March 1, 1884. Available at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

- 26.Bliss M. William Osler, A Life in Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chesney AM. William Henry Welch, a Tribute on the Centenary of his Birth, April 1950. Available at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.