Abstract

Fungi associated with the marine sponge Tethya aurantium were isolated and identified by morphological criteria and phylogenetic analyses based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. They were evaluated with regard to their secondary metabolite profiles. Among the 81 isolates which were characterized, members of 21 genera were identified. Some genera like Acremonium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, Phoma, and Trichoderma are quite common, but we also isolated strains belonging to genera like Botryosphaeria, Epicoccum, Parasphaeosphaeria, and Tritirachium which have rarely been reported from sponges. Members affiliated to the genera Bartalinia and Volutella as well as to a presumably new Phoma species were first isolated from a sponge in this study. On the basis of their classification, strains were selected for analysis of their ability to produce natural products. In addition to a number of known compounds, several new natural products were identified. The scopularides and sorbifuranones have been described elsewhere. We have isolated four additional substances which have not been described so far. The new metabolite cillifuranone (1) was isolated from Penicillium chrysogenum strain LF066. The structure of cillifuranone (1) was elucidated based on 1D and 2D NMR analysis and turned out to be a previously postulated intermediate in sorbifuranone biosynthesis. Only minor antibiotic bioactivities of this compound were found so far.

Keywords: Tethya aurantium, sponge-associated fungi, phylogenetic analysis, natural products, cillifuranone

1. Introduction

Natural products are of considerable importance in the discovery of new therapeutic agents [1]. Apart from plants, bacteria and fungi are the most important producers of such compounds [2]. For a long time neglected as a group of producers of natural products, marine microorganisms have more recently been isolated from a variety of marine habitats such as sea water, sediments, algae and different animals to discover new natural products [3,4]. In particular, sponges which are filter feeders and accumulate high numbers of microorganisms have attracted attention [5,6]. Though the focus of most of these investigations was concerned with the bacteria, a series of investigations identified marine sponges also as a good source of fungi [7–18]. Due to the accumulation of microorganisms, it is no surprise that sponges account for the majority of fungal species isolated from the marine realm [19]. However, the type of association and a presumable ecological function of accumulated fungi in sponges remain unclear and little evidence is available on fungi specifically adapted to live within sponges. One example is represented by fungi of the genus Koralionastes, which are known to form fruiting bodies only in close association with crustaceous sponges associated with corals [20].

Consistently, fungi isolated from sponges account for the highest number (28%) of novel compounds reported from marine isolates of fungi [19]. Marine isolates of fungi evidently are a rich source of chemically diverse natural products which has not been consequently exploited so far. Among a number of metabolites from sponge-associated fungi with promising biological activities are the cytotoxic gymnastatins and the p56lck tyrosine kinase inhibitor ulocladol [21,11]. In view of these exciting data and our own previous work on the bacterial community associated with Tethya aurantium [22], we have now isolated and identified a larger number of fungi from this sponge. In European waters, Tethya aurantium is commonly found in the Atlantic Ocean, the English Channel, the North Sea as well as the Mediterranean Sea, where our specimens originated from [23]. Except for a single report from Indriani [24], fungi associated with Tethya sp. have not been investigated so far. The formation of natural products by these fungi and their biotechnological potential has not been evaluated yet.

For the identification of the fungal isolates from Tethya aurantium, we combined morphological criteria and phylogenetic analyses based on the sequence of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions 1 and 2. On the basis of their classification, strains were selected for analysis of their ability to produce natural products. In addition to a number of known compounds, the new cyclodepsipeptides scopularide A and B were produced by a Scopulariopsis brevicaulis isolate [25]. Because of their antiproliferative activities against several tumor cell lines, these peptides and their activities have been patented [26]. During the present study, we have isolated four so far undescribed substances. Structure and properties of the new cillifuranone, a secondary metabolite from Penicillium chrysogenum strain LF066 are reported here.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of the Fungal Strains Isolated from T. aurantium

In most studies on fungi associated with sponges the taxonomic classification of the fungi was based exclusively on morphological characteristics and in many cases identification was possible only at the genus level [17]. This can be attributed to the fact that taxonomic identification of fungi at the species level is not always easy. It is impaired by the fact that under laboratory conditions many fungi do not express reproductive features like conidia or ascomata, which represent important traits for identification. These fungi are classified as “mycelia sterilia”.

Therefore, morphological criteria as well as sequence information and the determination of phylogenetic relationships are considered to be necessary for the identification of fungi. Consequently, we have combined the morphological characterization with a PCR-based analysis using ITS1-5.8S-rRNA-ITS2 gene sequences to identify 81 fungi isolated from Tethya aurantium. Based on these criteria the strains could be identified to the species level (Figure 1, Table 1).

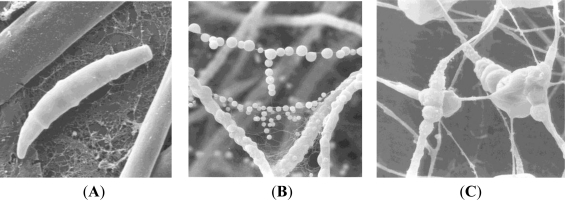

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrographs of Fusarium sp. strain LF236. (A) Multicellular, curved conidiospore; (B) Exudates in the surface layer of a liquid culture; (C) Intercalary chlamydospores in the mycelium.

Table 1.

Identification of fungal strains isolated from Tethya aurantium samples based on morphological criteria as well as genetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Closest relatives to fungal strains according to BLAST search are presented. In case BLAST search yielded a cultured but undesignated strain as closest relative, the closest cultured and the designated relative is given additionally.

| Strain | Morphological identification | Seq. length (nt) | Next related cultivated strain (BLAST) | Acc. No. | Similarity (%) | Overlap (nt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF063 | Cladosporium sp. | 483 | Fungal sp. ARIZ AZ0920 Cladosporium sphaerospermum isolate KH00280 |

HM123596.1 GU017501.1 |

99 99 |

482 482 |

| LF064 | Scopulariopsis murina | 473 | Ascomycota sp. 840 Phialemonium obovatum strain CBS 279.76 |

GU934604.1 AB278187.1 |

92 89 |

360 340 |

| LF065 | Penicillium sp. | 546 | Penicillium glabrum strain 4AC2K | GU372904.1 | 99 | 545 |

| LF066 | Penicillium sp. | 551 | Penicillium chrysogenum strain JCM 22826 | AB479305.1 | 99 | 549 |

| LF073 | Aspergillus sp. | 533 | Aspergillus versicolor isolate UOA/HCPF 8709 | FJ878627.1 | 100 | 532 |

| LF177 | Alternaria sp. | 568 | Lewia infectoria strain IA310 | AY154718 | 99 | 561 |

| LF178 | Cladosporium sp. | 479 | Fungal endophyte sp. g6 Cladosporium cladosporioides strain CC1 |

HM537022.1 HM210839.1 |

100 100 |

479 479 |

| LF179 | Mycelia sterilia | 559 | Fungal endophyte isolate 9137 Paraphaeosphaeria sp. LF6 |

EF419991.1 GU985234.1 |

100 99 |

555 557 |

| LF183 | Cladosporium sp. | 523 |

Dothideomycetes sp. 11366 Cladosporium cladosporioides isolate SLP001 |

GQ153254.1 FJ932747.1 |

99 99 |

522 521 |

| LF184 | Cladosporium sp. | 475 | Fungal endophyte sp. g6 Cladosporium cladosporioides strain CC1 |

HM537022.1 HM210839.1 |

100 100 |

475 475 |

| LF236 | Fusarium sp. | 512 |

Fusarium sp. CPK3469 Gibberella intricans strain ATCC MYA-3861 |

FJ827615.1 GU291255.1 |

99 99 |

511 511 |

| LF237 | Fusarium sp. | 503 |

Fusarium sp. CPK3337 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 36478 |

FJ827616.1 GQ505743.1 |

100 100 |

503 503 |

| LF238 | Fusarium sp. | 513 |

Fusarium sp. CPK3469 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 36478 |

FJ827615.1 GQ505743.1 |

100 100 |

513 513 |

| LF239 | Fusarium sp. | 509 |

Fusarium sp. NRRL 45997 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 36478 |

GQ505761.1 GQ505743.1 |

99 99 |

503 503 |

| LF240 | Mycelia sterilia | 528 |

Lewia sp. B32C Lewia infectoria strain IA241 |

EF432279.1 AY154692.1 |

99 99 |

525 525 |

| LF241 | Mycelia sterilia | 513 |

Botryosphaeria sp. GU071005 Sphaeropsis sapinea strain CBS109943 |

AB472081.1 DQ458898.1 |

100 100 |

512 512 |

| LF242 | Penicillium sp. | 538 | Penicillium brevicompactum isolate H66s1 | EF634441.1 | 99 | 537 |

| LF243 | Penicillium sp. | 532 | Penicillium virgatum strain IHB F 536 | HM461858.1 | 100 | 530 |

| LF244 | Cladosporium sp. | 516 | Fungal endophyte sp. g2 Davidiella tassiana strain BLE25 |

HM537019.1 FN868485.1 |

99 99 |

516 516 |

| LF245 | Fusarium sp. | 494 |

Fusarium sp. CPK3514 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 13402 |

FJ840530.1 GQ505681.1 |

100 100 |

494 494 |

| LF246 | Volutella sp. | 548 | Volutella ciliata strain BBA 70047 | AJ301966.1 | 99 | 547 |

| LF247 | Fusarium sp. | 520 |

Fusarium sp. LD-135 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 13402 |

EU336989.1 GQ505681.1 |

99 99 |

509 504 |

| LF248 | Botrytis sp. | 504 | Fungal endophyte sp. g18 Botryotinia fuckeliana strain OnionBC-1 |

HM537028.1 FJ169667.2 |

100 100 |

504 504 |

| LF249 | Penicillium sp. | 552 |

Penicillium sp. BM Penicillium commune isolate HF1 |

GU566211.1 GU183165.1 |

99 99 |

551 551 |

| LF250 | Penicillium sp. | 564 | Penicillium chrysogenum strain ACBF 003-2 | GQ241341.1 | 97 | 547 |

| LF251 | Penicillium sp | 550 |

Penicillium sp. F6 Penicillium chrysogenum strain ACBF 003-2 |

GU566250.1 GQ241341.1 |

100 100 |

550 550 |

| LF252 | Fusarium sp | 513 |

Fusarium sp. NRRL 45997 Fusarium equiseti strain NRRL 36478 |

GQ505761.1 GQ505743.1 |

99 99 |

511 511 |

| LF253 | Trichoderma sp. | 543 | Hypocrea lixii strain OY3207 | FJ571487.1 | 100 | 540 |

| LF254 | Clonostachys sp | 525 | Bionectria ochroleuca strain G11 | GU566253.1 | 100 | 524 |

| LF255 | Alternaria sp | 518 | Fungal endophyte sp. g76 Alternaria alternata strain 786949 |

HM537053.1 GU594741.1 |

100 100 |

518 518 |

| LF256 | Botrytis sp. | 535 | Beauveria bassiana strain G61 | GU566276.1 | 99 | 533 |

| LF257 | Cladosporium sp. | 495 | Davidiella tassiana strain G20 | GU566258.1 | 100 | 495 |

| LF258 | Phoma sp. nov. | 538 | Fungal sp. GFI 146 Septoria arundinacea isolate BJDC06 |

AJ608980.1 GU361965.1 |

93 91 |

470 460 |

| LF259 | Penicillium sp. | 522 | Penicillium brevicompactum strain: JCM 22849 | AB479306.1 | 100 | 522 |

| LF260 | Sphaeropsidales | 508 | Pyrenochaeta cava isolate olrim63 | AY354263.1 | 100 | 508 |

| LF491 | Aspergillus sp. | 555 | Petromyces alliaceus isolate NRRL 4181 | EF661556.1 | 99 | 555 |

| LF494 | Fusarium sp. | 469 | Fusarium sp. CB-3 | GU932675.1 | 100 | 469 |

| LF496 | Mycelia sterilia | 531 | Verticillium sp. TF17TTW | FJ948142.1 | 99 | 529 |

| LF501 | Aspergillus sp. | 514 | Aspergillus granulosus isolate NRRL 1932 | EF652430.1 | 100 | 514 |

| LF508 | Not identified | 501 | Phoma sp. W21 | GU045305.1 | 99 | 497 |

| LF509 | Fusarium sp. | 504 | Fusarium sp. CPK3514 | FJ840530.1 | 99 | 503 |

| LF510 | Fusarium sp. | 516 | Fusarium sp. FL-2010c isolate UASWS0396 | HQ166535.1 | 99 | 514 |

| LF514 | Trichoderma sp. | 546 | Trichoderma sp. TM9 | AB369508.1 | 100 | 546 |

| LF526 | Eurotium sp. | 486 |

Eurotium sp. FZ Eurotium chevalieri isolate UPM A11 |

HQ148160.1 HM152566.1 |

100 100 |

486 486 |

| LF530 | Alternaria sp. | 522 | Alternaria sp. 7 HF-2010 | HQ380788.1 | 100 | 522 |

| LF534 | Penicillium sp. | 540 | Penicillium roseopurpureum strain E2 | GU566239.1 | 99 | 536 |

| LF535 | Acremonium sp. | 525 |

Acremonium sp. FSU2858 Lecanicillium lecanii strain V56 |

AY633563.1 DQ007047.1 |

99 99 |

523 510 |

| LF537 | Cladosporium sp. | 503 | Cladosporium cladosporioides strain F12 | HQ380766.1 | 100 | 503 |

| LF538 | Mucor hiernalis | 598 | Mucor hiemalis isolate UASWS0442 | HQ166553.1 | 100 | 598 |

| LF540 | Not identified | 578 | Hypocrea lixii isolate FZ1302 | HQ259308.1 | 99 | 575 |

| LF542 | Mycelia sterilia | 458 |

Peyronellaea glomerata isolate NMG_27 Phoma pomorum var. pomorum strain CBS 539.66 |

HM776432 FJ427056.1 |

99 99 |

457 457 |

| LF543 | Alternaria sp. | 522 | Alternaria citri strain IA265 | AY154705.1 | 100 | 522 |

| LF547 | Aspergillus sp. | 539 | Aspergillus minutus isolate NRRL 4876 | EF652481.1 | 98 | 529 |

| LF550 | Mycelia sterilia | 524 |

Bartalinia robillardoides CBS:122686 Ellurema sp. 42-3 |

EU552102.1 AY148442.1 |

99 99 |

522 514 |

| LF552 | Epicoccum nigrum | 506 | Epicoccum nigrum strain GrS7 | FJ904918.1 | 99 | 503 |

| LF553 | Aspergillus sp. | 528 | Aspergillus sp. Da91 | HM991178.1 | 100 | 528 |

| LF554 | Aspergillus sp. | 525 | Aspergillus sp. Da91 | HM991178.1 | 100 | 525 |

| LF557 | Mycelia sterilia | 528 |

Fusarium sp. FL-2010f Fusarium oxysporum strain TS08-137-1-1 |

HQ166539.1 AB470850.1 |

99 | 522 |

| LF558 | Not identified | 498 | Phoma sp. W21 | GU045305.1 | 100 | 498 |

| LF562 | Tritirachium sp. | 504 | Tritirachium sp. F13 | EU497949.1 | 99 | 498 |

| LF563 | Trichoderma sp. | 537 | Hypocrea lixii isolate DLEN2008014 | HQ149778.1 | 100 | 537 |

| LF576 | Clonostachys sp. | 504 | Bionectria cf. ochroleuca CBS 113336 | EU552110.1 | 99 | 503 |

| LF577 | Penicillium sp. | 538 | Penicillium brevicompactum isolate NMG_25 | HM776430.1 | 99 | 534 |

| LF580 * | Scopulariopsis brevicaulis | 916 | Scopulariopsis brevicaulis strain NCPF 2177 | AY083220.1 | 99 | 686 |

| LF581 | Fusarium sp. | 504 | Fusarium sp. NRRL 45996 | GQ505760.1 | 99 | 502 |

| LF584 | Aspergillus sp. | 543 | Aspergillus sp. N13 | GQ169453.1 | 99 | 542 |

| LF590 | Penicillium sp. | 522 | Penicillium citreonigrum strain Gr155 | FJ904848.1 | 100 | 522 |

| LF592 | Paecilomyces sp. | 544 | Fungal endophyte sp. P1201A Paecilomyces lilacinus strain CG 271 |

EU977225.1 EU553303.1 |

99 98 |

541 516 |

| LF594 | Mycelia sterilia | 531 |

Fusarium sp. FL-2010c Fusarium acuminatum strain NRRL 54217 |

HQ166535.1 HM068325.1 |

99 99 |

527 527 |

| LF596 | Penicillium sp. | 529 |

Penicillium sp. FF24 Penicillium canescens strain QLF83 |

FJ379805.1 FJ025212.1 |

100 100 |

529 529 |

| LF607 | Penicillium sp. | 532 |

Penicillium sp. 17-M-1 Penicillium sclerotiorum strain SK6RN3M |

EU076929.1 EU807940.1 |

99 99 |

523 520 |

| LF608 | Cladosporium sp. | 495 | Fungal sp. mh2981.6 Cladosporium cladosporioides strain CC1 |

GQ996077.1 HM210839.1 |

100 100 |

495 495 |

| LF610 | Clonostachys sp. | 528 | Fungal sp. mh2053.3 Bionectria ochroleuca isolate Rd0801 |

GQ996069.1 HQ115728.1 |

99 99 |

524 524 |

| LF626 | Mycelia sterilia | 588 | Trichoderma cerinum isolate C.P.K. 3619 | GU111565.1 | 99 | 586 |

| LF627 | Aspergillus sp. | 509 | Aspergillus sp. 4-1 | HQ316558.1 | 100 | 509 |

| LF629 | Mycelia sterilia | 510 | Cladosporium cladosporioides strain F12 | HQ380766.1 | 99 | 509 |

| LF630 | Penicillium sp. | 518 | Penicillium brevicompactum isolate H66s1 | EF634441.1 | 100 | 518 |

| LF631 | Epicoccum nigrum | 514 | Epicoccum nigrum strain AZ-1 | DQ981396.1 | 99 | 512 |

| LF634 | Aspergillus sp. | 581 | Aspergillus terreus isolate UOA/HCPF 10213 | GQ461911.1 | 99 | 579 |

| LF644 | Clonostachys sp | 528 | Bionectria rossmaniae strain CBS 211.93 | AF210665.1 | 99 | 521 |

| LF646 | Mycelia sterilia | 510 | Cladosporium cladosporioides strain F12 | HQ380766.1 | 99 | 509 |

A = anamorph; T = teleomorph; Alternaria (A) = Lewia (T); Aspergillus (A) = Petromyces (T) and Eurotium (T); Beauveria (A) = Cordyceps (T); Botrytis (A) = Botryotinia (T); Cladosporium (A) = Davidiella (T); Fusarium (A) = Gibberella (T); Clonostachys (A) = Bionectria (T); Trichoderma (A) = Hypocrea (T); Phoma = Pleurophoma (synonym); nt = nucleotides;

phylogenetic data to LF580 are derived from the 18S rRNA gene sequence.

First of all, morphological criteria enabled the identification of most of the fungal isolates at the genus level (Table 1). However, under the culture conditions applied, 11 strains did not produce spores and were designed as “mycelia sterilia”. A morphological classification of these strains was not possible. Despite the formation of spores, another four strains could not be classified on the basis of morphological characteristics.

In order to verify the results of the morphological examination and identify the strains at the species level, they were subjected to ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 gene sequence analysis. The results obtained from this sequence analysis corresponded well with those from the morphological identification (Table 1, Figure 2) and in addition allowed identification of those strains not identified microscopically. In most cases, the sequence data and the phylogenetic relationships allowed the identification at the species level. Results from BLAST search are depicted in Table 1. Taking together morphological and genetic characteristics, most isolates belong to the Ascomycotina with representatives of the fungal classes Dothideomycetes (24 isolates), Eurotiomycetes, (25 isolates), Sordariomycetes (30 isolates) and Leotiomycetes (1 isolate). Only a single isolate (strain LF538) was classified as belonging to the Mucoromycotina.

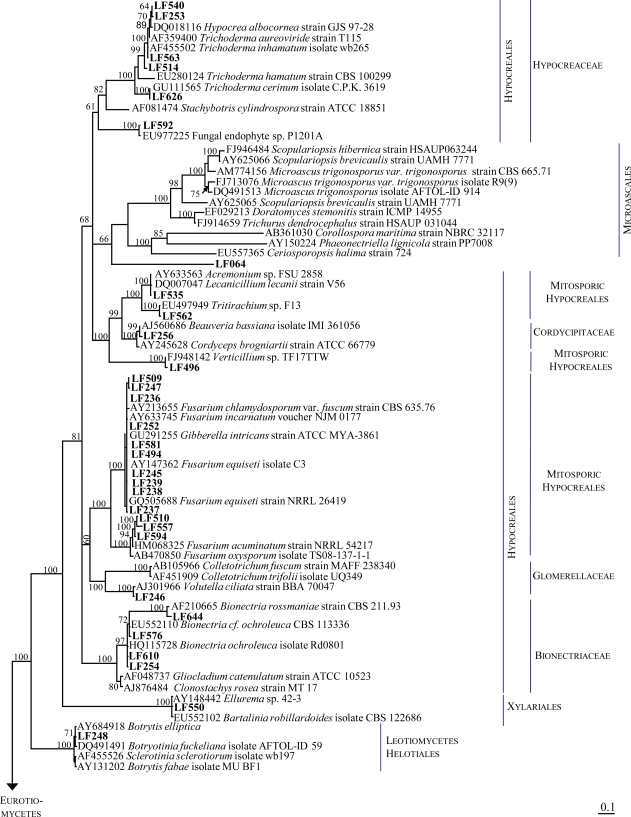

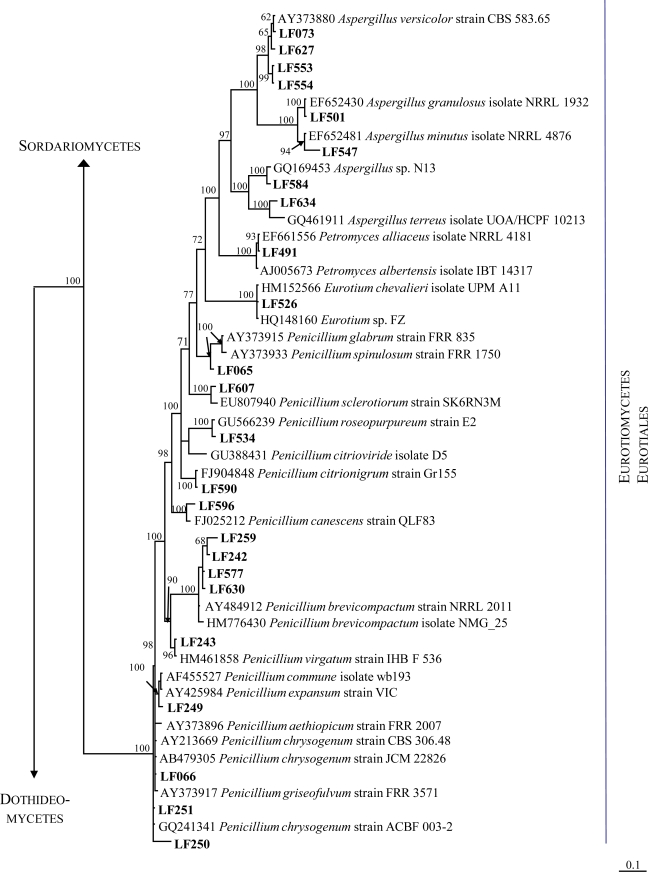

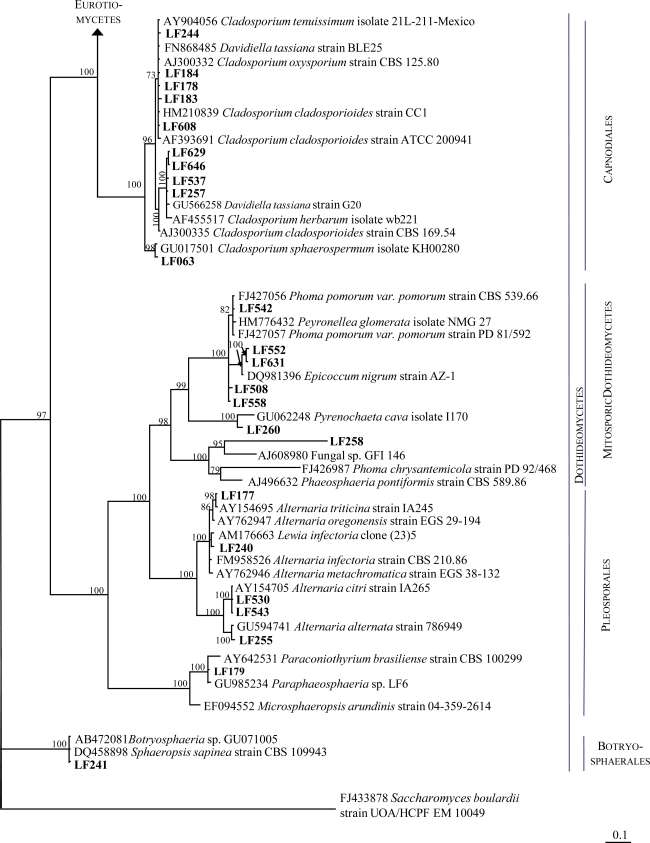

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic consensus tree based on ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 gene sequences calculated by Bayesian inference assuming the general time reversible (GTR) model (6 substitution rate parameters, gamma-shaped rate variation, proportion of invariable sites). Isolates from Tethya aurantium obtained during this study are printed in bold. Numbers on nodes indicate Bayesian posterior probability values. nt = nucleotides.

As shown in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2), 10 isolates of the Dothideomycetes closely affiliated to fungal species of the order Capnodiales (Cladosporium spp. and its teleomorph Davidiella). Within the order Pleosporales (13 isolates) 5 isolates were closely related to Alternaria sp., including Lewia infectoria as teleomorph. From the same order we also isolated 2 strains of the species Epicoccum nigrum and 1 Paraphaeosphaeria strain. Furthermore, 5 isolates of the genus Phoma were found, of which one isolate (strain LF258) shows only 91% sequence similarity to Septoria arundinacea as next relative according to BLAST results (Table 1) and presumably represents a new species in the Phoma lineage. The low similarity of this isolate to known sequences is also reflected in the position in the phylogenetic tree, clustering distinct from other Phoma species. A single isolate (strain LF241) was assigned to Sphaeropsis sapinea/Botryosphaeria sp. within the order Botryosphaeriales in the class Dothideomycetes.

All 25 isolates assigned to the class Eurotiomycetes were affiliated to the order Eurotiales and are represented by 14 isolates closely affiliating to Penicillium species (P. glabrum, P. virgatum/ P. brevicompactum, P. griseofulvum/P. commune, P. chrysogenum, P. sclerotiorum/P. citreonigrum, P. citreoviride/P. roseopurpureum, P. canescens), 10 representatives of the genus Aspergillus (including 2 of its teleomorphs, Petromyces alliaceus and Eurotium chevalieri) and 1 isolate of Paecilomyces.

The 30 isolates affiliated to the class Sordariomycetes were grouped into the orders Hypocreales (26 isolates), Microascales (2 isolates) and Xylariales (1 isolate). Within the Hypocreales, one isolate each was closely related to Beauveria bassiana (strain LF256), Tritirachium album (strain LF562), Verticillium sp. (strain LF496), and Volutella ciliata (strain LF246). The most frequent genera within this order were Fusarium (13 isolates), Trichoderma (5 isolates, including Hypocrea teleomorphs) and Clonostachys (4 isolates, including teleomorphs of Bionectria). The Microascales were represented by two isolates of the genus Scopulariopsis. One of these (strain LF064), morphologically classified as Scopulariopsis murina, was distantly related to the next cultured relative (89% according to BLAST search) and appears as a sister group to the Scopulariopsis lineage in the phylogenetic tree. The order Xylariales was represented by only a single isolate (strain LF550), Bartalinia robillardoides. As the only representatives of the order Helotiales within the class Leotiomycetes strain LF248 was closely related to Botryotinia fuckeliana.

The combination of microscopic and genetic analyses has proven to be a reliable method for the identification of fungal isolates and results from both approaches corresponded quite well (Table 1, Figure 2). The reliable identification of isolates is a fundamental prerequisite in order to characterize the producers of marine natural products [3], to determine the occurrence of fungal species in different habitats, and to correlate distinct secondary metabolite patterns to fungal species. Therefore, we highly recommend that morphological identification of fungal isolates consequently should be verified by molecular means and thus raise the number of reliably identified species in public databases.

A number of investigations, mainly with the aim of finding novel natural products, showed that most marine sponges harbor a plethora of cultivable fungi within their tissue [10–15,18]. Despite the large number of fungi isolated from sponges, a selective accumulation of specific taxa within sponges and a truly marine nature of these fungi is doubted, which is why they are commonly referred to as “marine-derived” [27,28]. In fact, it could be shown that the phylogenetic diversity of fungi isolated from different sponges varies [17]. It has also been stated that the taxa frequently isolated from sponges resemble those described from terrestrial habitats [11,16,28]. This is in good accordance with our results, showing representatives of Acremonium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, Phoma, and Trichoderma to be abundant in Tethya aurantium and with those of Wang (2006) demonstrating that they also are widely distributed among different sponges from various locations [29]. Although it appears that the marine environment indeed provides various habitats for fungi, this has rarely been demonstrated. Nonetheless, due to the accumulation of fungi within sponges a large number of strains can be isolated which increases the probability to find representatives of less common taxa which might produce unprecedented secondary metabolites. For example, fungi belonging to the genera Beauveria, Botryosphaeria, Epicoccum, Tritirachium, and Paraphaeosphaeria have rarely been obtained from marine sponges [11,18,24] and, to the best of our knowledge, we have isolated Bartalinia sp. and Volutella sp. from a marine sponge for the first time.

Although evidence is presented that some bacterial symbionts of sponges are the producers of metabolites originally assumed to be produced by the sponge [4], equivalent evidence for fungi is lacking. There is actually little evidence for sponge-specific fungal associations and the only reports on this matter deals with the above mentioned Koralionastes species and a yeast living in symbiosis with the sponge Chondrilla sp. [30]. In fact, most of the studies had the biotechnological potential of sponge-derived fungi in mind but not the ecological role. Our culture-dependent approach was not considered to approach the aspect of specificity of the association with the sponge and molecular-based studies would be more suited to identify specifically sponge-associated fungi.

2.2. Secondary Metabolite Analyses

With the cultivation-based approach used in this study, we obtained a variety of strains from a surprisingly broad range of phylogenetic groups of fungi. A selection of the isolated and identified fungi was subjected to analysis of their secondary metabolite profiles. Strains were selected in order to represent a wide spectrum of genera, representatives of a variety of different genera, some known to include strains and species known for the production of secondary metabolites others from less common taxa. Some of the strains selected according to systematic criteria did not produce detectable amounts of secondary metabolites under the applied culture conditions. Unraveling their potential of secondary metabolite production will require more intense studies. Those extracts which did contain at least one compound in significant amounts were analyzed by HPLC with DAD (UV)- and MS-detection and the metabolites which could be identified are listed in Table 2. A high percentage of the substances identified this way could be verified by 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Table 2). The majority of these metabolites have been reported from fungi before. Two of our previous reports on metabolites from fungi isolated from Tethya aurantium deal with the antiproliferative scopularides A–B [25,26] and the sorbifuranones A–C [31].

Table 2.

Secondary metabolites identified in extracts of fungi isolated from the sponge Tethya aurantium.

| Genus | Strain | Compound | Reported from a | Bioactivity a,b | Method of dereplication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria | LF177 | infectopyrone | Alternaria infectoria, Leptosphaeria maculans/Phoma lingum | UV, MS, NMR | |

| phomenin A & B | Phoma tracheiphila, Leptosphaeria maculans/Phoma lingum, Ercolaria funera | phytotoxin | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| Aspergillus | LF627 | sterigmatocystin | Aspergillus versicolor, Chaetomium | mycotoxin [32] | UV, MS |

| notoamid D | Aspergillus sp. | UV, MS | |||

| stephacidin A | Aspergillus ochraceus | cytotoxic | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| LF547 | cinereain | Botrytis cinerea | plant growth regulator, phytotoxin | UV, MS, NMR | |

| (2′E,4′E,6′E)-6-(1′-carboxyocta-2′,4′,6′-trien)-9-hydroxydrim-7-ene-11,12-olide | Aspergillus ustus | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| (2′E,4′E,6′E)-6-(1′-carboxyocta-2′,4′,6′-trien)-9-hydroxydrim-7-ene-11-al | Aspergillus ustus | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| compound A | hit in Scifinder [33], but no publication available | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| compound B | no hit in database | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| LF553 | sydonic acid | Aspergillus sydowii | weakly antibacterial [34] | UV, MS, NMR | |

| hydroxysydonic acid | Aspergillus sydowii | UV, MS | |||

| LF584 | WIN-6 6306 | Aspergillus flavipes | substance P antagonist, inhibition of HIV-1 integrase [35] | UV, MS | |

| aspochalasines | Aspergillus flavipes and other Aspergillus sp. | antibiotic, moderately cytotoxic [36] | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| Aspergillus/ Petromyces | LF491 | isokotanin A–C | Aspergillus alliaceus and Petromyces alliaceus | moderate antiinsectan activities [37] | UV, MS, NMR |

| 14-(N,N-Dimethyl-l-leucinyloxy)paspalinine | Aspergillus alliaceus | potassium channel antagonist [38] | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| nominine or a similar indoloditerpene | Aspergillus nomius, Aspergillus flavus, Petromyces alliaceus | insecticidal properties | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| Phoma | LF258 | monocerin | Helminthosporium monoceras, Fusarium larvarum, Dreschlera ravenelii, Exserohilum rostratum, Readeriella mirabilis | antifungal, insecticidal and phytotoxic properties | UV, MS |

| intermediate in the bio-synthesis of monocerin | Dreschlera ravenelii | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| evernin- or isoeverninaldehyde | Guignardia laricina | weak phytotoxin | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| Epicoccum | LF552 | epicoccamide | Epicoccum purparescens and other Epicoccum sp., Aurelia aurita | UV, MS | |

| orevactaene | Epicoccum nigrum | binding inhibitor of HIV-1 rev protein to Rev response element (RRE) | UV, MS | ||

| Eurotium | LF526 | echinulin | Eurotium repens, Aspergillus amstelodami, Aspergillus echinulatus, Aspergillus glaucus | experimentally hepatic and pulmonary effects | UV, MS |

| neoechinulines | Aspergillus amstelodami | antioxidative activity | UV, MS | ||

| auroglaucines and flavoglaucine | Aspergillus and Eurotium spp. | mycotoxin, shows antineo-plastic properties [39] | UV, MS | ||

| Fusarium | LF236 | equisetin | Fusarium equiseti and Fusarium heterosporum | antibacterial activity, inhi-bition of HIV-1 integrase | UV, MS, NMR |

| LF238 | equisetin | Fusarium equiseti and Fusarium heterosporum | antibacterial activity, inhi-bition of HIV-1 integrase | UV, MS, NMR | |

| fusarins | Fusarium moniliforme | mutagenic [40] | UV, MS | ||

| LF594 | enniatine | various Fusarium sp. | ionophore, insecticidal, ACAT inhibition, GABA receptor binding | UV, MS | |

| Paecilomyces | LF592 | leucinostatins | Paecilomyces lilacinus and other Paecilomyces sp. | active against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi | UV, MS |

| Penicillium | LF066 | compound C | no hit in database | UV, MS, NMR | |

| meleagrin | Penicillium meleagrinum and Penicillium chrysogenum | structurally similar to tremorgenic mycotoxins | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| roquefortin C | Penicillium roquefortii and other Penicillium sp. | neurotoxin | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| sorbifuranones A–C | Penicillium chrysogenum [31] | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| 2′,3′-dihydrosorbicillin | Penicillium notatum, Verticillium intertextum | weakly antibacterial [41] | UV, MS | ||

| bisvertonolone | Penicillium chrysogenum, Verticillium intertextum, Acremonium strictum, Trichoderma longibrachiatum | β-1,6glucan biosynthesis inhibitor, antioxidative, inducer of hyphal malformation in fungi | UV, MS | ||

| ergochromes | Aspergillus ochraceus, Claviceps purpurea, Aspergillus aculeatus, Gliocladium sp., Penicillium oxalicum, Phoma terrestris, Pyrenochaeta terrestris | teratogenic effects | UV, MS | ||

| LF259 | mycophenolic acid | Penicillium brevicompactum and other Penicillium sp. | antineoplastig, antiviral immunosuppressant properties, useful in treating psoriasis and leishmaniasis, | UV, MS | |

| LF590 | citreoviridins | Penicillium citreoviride, Penicillium toxicarium, Penicillium ochrosalmoneum, Aspergillus terreus | neurotoxic | UV, MS, NMR | |

| territrem B | Penicillium sp. and Aspergillus terreus | inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase | UV, MS | ||

| LF607 | sclerotiorin | Penicillium sclerotiorum and Penicillium multicolor | inhibits cholesterin ester transfer protein activity | UV, MS | |

| sclerotioramine | UV, MS, NMR | ||||

| compound D | no hit in database | UV, MS, NMR | |||

| Penicillium | LF596 | griseofulvin | Penicillium griseofulvum and other Penicillium sp. | antifungal, possible human carcinogen | UV, MS, NMR |

| tryptoquivalin | Aspergillus clavatus | tremorgenic toxin | UV, MS | ||

| nortryptoquivalin | Aspergillus clavatus and Aspergillus fumigatus | tremorgenic toxin | UV, MS | ||

| fiscalins A and C | Neosartorya fischeri | substance P inhibitor, neurokinin binding inhibitor | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| Scopulariopsis | LF580 | scopularide A and B | Scopulariopsis brevicaulis | antiproliferative [25,26] | UV, MS, NMR |

| Clonostachys | LF254 | T-988B | Tilachlidium sp. | cytotoxic | UV, MS, NMR |

| bionectin B | Bionectria byssicola | antibacterial (MRSA) | UV, MS, NMR | ||

| verticillin C | Verticillium sp. | antibiotic | UV, MS |

According to the Dictionary of Natural Products [42] if not stated otherwise;

blank cells indicate that no entry concerning bioactivity in the Dictionary of Natural Products was available and no report on bioactivity was found.

For four compounds, database searches [33,42–43] did not lead to a hit (B, C, D) or no publication was available (A). The structure elucidations of compounds A and B, metabolites with modified diketopiperazine substructures, and compound D, a new azaphilone derivative, are in progress. Compound C was identified as the new metabolite cillifuranone and its structure is described in the following.

Penicillium strain LF066, the producer of cillifuranone, was singled out for further investigations, because first surveys proved it to be a very potent producer of secondary metabolites. From the same strain, sorbifuranone B and C as well as 2′,3′-dihydrosorbicillin have already been described by Bringmann et al. [31] and it was obvious that the full potential of the strain had not been exploited, yet. Further analysis led to the detection of xanthocillines and sorbifuranones and the isolation of sorbifuranone B, meleagrin, roquefortin C, a couple of ergochromes as well as the new cillifuranone (1) whose structure was elucidated based on 1D and 2D NMR experiments.

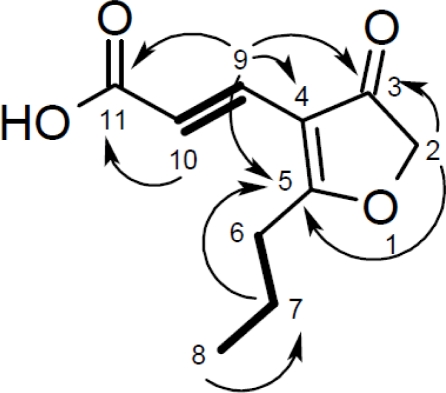

The 13C NMR spectrum of 1 displayed 10 clearly distinguishable carbon signals which was in good agreement with the molecular formula C10H12O4, deduced from the result of a HRESI-MS measurement (calculated for C10H12O4Na 219.0628, measured 219.0627). The carbon signals included resonances belonging to three carbonyl or enol carbons (δC 170.9, 196.7 and 201.7), three sp3 hybridized methylene carbons (δC 20.9, 31.6 and 76.3), one methyl group (δC 14.0), two olefinic methines (δC 118.5 and 133.0) and finally one quaternary olefinic carbon (δC 112.6). The structure of the molecule could be delineated from 1D (1H, 13C and DEPT) and 2D NMR (1H-13C HSQC, 1H-1H COSY and 1H-13C HMBC) spectra. From the 1H-1H COSY spectrum two separate spin systems could be identified. The first one consisted of the olefinic methine groups CH-9 (δC 133.0, δH 7.32) and CH-10 (δC 118.5, δH 6.83), forming an E-configured double bond as proven by their 3J coupling constant of 16 Hz. The corresponding protons H-9 and H-10 both showed 1H-13C HMBC correlations to the carboxyl carbon C-11 (δC 170.9) as well as to the quarternary carbons of the furanone ring, C-3 (δC 201.7) to C-5 (δC 196.7). C-3 was the ketone carbonyl group included in the furanone substructure which was in accordance with its chemical shift. C-4 (δC 112.6) and C-5 were also part of the furanone and formed a tetrasubstituted double bond in which C-5 was located adjacent to an oxygen atom. Compared to an unsubstituted enol, the resonance of C-5 was shifted further downfield due to the conjugation of the double bond Δ4,5 with the carbonyl carbon C-3. Apart from C-9 of the double bond Δ9,10, the carbonyl carbon C-3 and the oxygen atom of the furanone ring, Δ4,5 was also connected to C-6 of the second spin system consisting of the methylene groups CH2-6 (δC 31.6, δH 2.76) and CH2-7 (δC 20.9, δH 1.76) as well as the methyl-group CH3-8 (δC 14.0, δH 1.03). Thus, the second spin system evidently was an n-propyl-chain. The furanone ring was completed with the methylene group CH2-2 (δC 76.3, δH 4.67). Its 1H and 13C shifts proved it to be linked to an oxyen atom, the 1H-13C HMBC correlations to C-3 and C-5 secured its exact position. Thus, the structure of cillifuranone (1) could be unambiguously determined (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Spin systems deduced from the 1H-1H COSY spectrum (bold) and selected 1H-13C HBMC correlations (arrows) relevant to the structure elucidation of cillifuranone (1).

Table 3.

NMR spectroscopic data of cillifuranone (1) in methanol-d4 (500 MHz).

|

Cillifuranone (1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δC, mult. | δH, (J in Hz) | COSY | HMBC |

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | 76.3, CH2 | 4.67, s | 6 | 3, 5, 6, 7 |

| 3 | 201.7, C | |||

| 4 | 112.6, C | |||

| 5 | 196.7, C | |||

| 6 | 31.6, CH2 | 2.76, t (7.5) | 2, 7 | 4, 5, 7, 8 |

| 7 | 20.9, CH2 | 1.76, sext. (7.5) | 6, 8 | 5, 6, 8 |

| 8 | 14.0, CH3 | 1.03, t (7.5) | 7 | 6, 7 |

| 9 | 133.0, CH | 7.32, d (16.0) | 10 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11 |

| 10 | 118.5, CH | 6.83, d (16.0) | 9 | 3, 4, 5, 9, 11 |

| 11 | 170.9, C | |||

Cillifuranone (1) was tested in a panel of bioassays evaluating the compound with respect to cytotoxic, antimicrobial and enzyme inhibitory activity. Very low activity was only found against Xanthomonas campestris (24% growth inhibition) and Septoria tritici (20% growth inhibition) at a concentration of 100 μM.

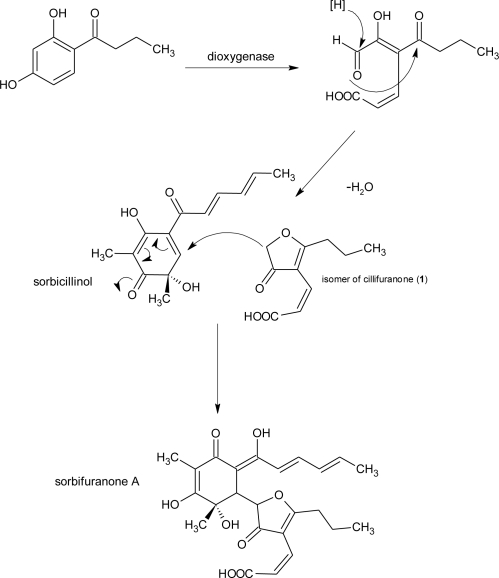

Strain LF066 was identified as Penicillium chrysogenum, a species that in our experience often produces metabolites deriving from sorbicillinol as a biosynthetic precursor (sorbicillinoids). The detection of bisvertinolone and the sorbifuranones in culture extracts of the fungus was consistent with this experience. Furanone substructures are abundant in natural products and can be found in metabolites from bacteria, fungi and plants [42] and presumably are products from different biosynthetic pathways [44–46]. From the genus Penicillium a number of furanone containing compounds has been described, including simple small molecules like penicillic acid, but also more complex ring structures such as the rotiorinols [47] or rugulovasines [48]. In most cases the furanone ring is a furan-2(5H)-one, whereas in cillifuranone (1) we have a furan-3(2H)-one. With that differentiation being made the number of related compounds gets fewer, furan-3(2H)-ones do not seem to be as ubiquituous as the furan-2(5H)-ones. From Penicillium strains, apart from the above mentioned sorbifuranones, berkeleyamide D [49] and trachyspic acid [50], both spiro compounds like sorbifuranone C, are examples. The new cillifuranone represents a substructure of the sorbifuranones, albeit with a different configuration of the exocyclic double bond, and represents the substructure which makes the sorbifuranones unique in the compound class of the sorbicillinoids. Just recently Bringmann et al. [31] published the structures of the sorbifuranones and postulated 1 to be an intermediate in their biosynthesis (Figure 4) which makes the isolation of 1 a very interesting result. The only difference between the postulated intermediate and our structure is, as stated above, the configuration of the double bond. However, in the crude extract of the strain, we detected two isomers with the same molecular weight and a very similar UV-spectrum, so that we assume that both isomers were present, but after the isolation process only the E-isomer was obtained, so that it might be the favoured configuration under the applied conditions.

Figure 4.

Biosynthesis of sorbifuranone A via Michael reaction of an isomer of cillifuranone (1) and sorbicillinol as postulated by Bringmann et al. (modified from [31]).

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Sampling Sites

The Limsky kanal (Canal di Lemme or Limsky channel) is a semi-closed fjord-like bay in the Adriatic Sea nearby Rovinj (Istrian Peninsula, Croatia). It is situated along an east-west axis, with an approximate length of 1 km and a maximum width of about 650 m and reaches a maximum depth of 32 m [51]. The sampling site was located at N45°7972′ and E13°43,734′.

3.2. Sponge Collection

Several specimens (13) of the Mediterranean sponge Tethya aurantium were collected by scuba diving. They were obtained in April 2003, June 2004, May 2005 and August 2006 in a depth of 5–15 m. The sponges were collected into sterile plastic bags, cooled on ice and transported immediately to the laboratory, where they were washed three times with sterile filtered seawater (0.2 μm). The sponge tissue was then cut into small pieces of approximately 0.1 cm3 each, which were either placed directly onto GPY agar plates (LF236 to LF255) or homogenized and diluted with membrane-filtered seawater (all other isolates).

3.3. Isolation, Cultivation and Storage of Fungi

Fungi were isolated on a low nutrient GPY agar, based on natural seawater of 30 PSU, containing 0.1% glucose, 0.05% peptone, 0.01% yeast extract and 1.5% agar. Small pieces of sponge tissue or 50 μL of the homogenate (undiluted or 1:10 or 1:100 diluted with sterile seawater) were used as inoculum. The agar plates were incubated for periods of 3 days to 4 weeks and were checked regularly for fungal colonies, which were then transferred to GPY agar plates. Pure cultures were used for morphological identification by light microscopy and for scanning electron microscopy. Fungal isolates were stored as agar slant cultures at 5 °C, and additionally were conserved at −80 °C using Cryobank vials (Mast Diagnostica).

3.4. Morphological Identification of Fungal Isolates

The morphology of GPY agar grown fungal isolates was studied using a stereo microscope (10–80× magnification) and a phase-contrast microscope (300–500× magnification). By this method, the majority of spore-producing isolates could be identified up to the generic level using the tables of Barnett and Hunter [52] and, for more detailed descriptions, the site of MycoBank [53]. Morphological identification of the selected pure cultures was supported by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy.

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

For electron microscopy, young GPY agar colonies were cut in 1 cm2 samples, transferred through an ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 90, 3 × 100%; each 15 min) and subsequently critical-point-dried in liquid carbon dioxide (Balzers CPD030). Samples were sputter-coated with gold-palladium (Balzers SCD004) and analyzed with a ZEISS DSM 940 scanning electron microscope.

3.6. Genetic Identification of Fungal Isolates and Phylogenetic Analysis

DNA-extraction was performed using the Precellys 24 system (Bertin Technologies). To one vial of a Precellys grinding kit with a glass beads matrix (diameter 0.5 mm, peqlab Biotechnologies GmbH) 400 μL DNAse-free water (Fluka) were added. Cell material from the fungal culture was then transferred to this vial and homogenized two times for 45 s at a shaker frequency of 6500. The suspension was centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 min and 15 °C. The supernatant was stored at −20 °C until further use in PCR.

Fungal specific PCR by amplifying the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 fragment was carried out using puReTaq™ Ready-To-Go™ PCR Beads (GE HEalthcare) with the ITS1 (5′-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′) primers according to White et al. [54]. PCR was conducted as follows: initial denaturation (2 min at 94 °C), 30 cycles of primer denaturation (40 s at 94 °C), annealing (40 s at 55 °C), and elongation (1 min at 72 °C) followed by a final elongation step (10 min at 72 °C). PCR products were checked for correct length (complete ITS1, 5.8S rRNA and ITS2 fragment length of Penicillium brevicompactum strain SCCM 10-I3 (EMBL-acc. No. EU587339 is 494 nucleotides), a 1% agarose gel in 1× TBE buffer (8.9 mM Tris, 8.9 mM borate, 0.2 mM EDTA).

PCR products were sequenced using the ABI PRISM® BigDye™ Terminator Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI PRISM® 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems). The ITS1 primer was used for sequencing. Sequence data were edited with ChromasPro Version 1.15 (Technelysium Pty Ltd.). Sequences from fungal strains obtained during this study were submitted to the EMBL database and were assigned accession numbers (FR822769-FR822849). Closest relatives were identified by sequence comparison with the NCBI Genbank database using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) [55]. Sequences were aligned using the ClustalX version 2.0 software [56] and the alignment was refined manually using BioEdit (version 7.0.9.0) [57]. For alignment construction, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 gene fragments from closest cultured relatives according to BLAST as well as type strains were used, whenever possible. However, not from all fungal species, ITS sequences from type strains were available in NCBI/Genbank. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 gene sequence of Saccharomyces boulardii strain UOA/HCPF EM10049 (acc. No. FJ433878) was used as outgroup sequence for phylogenetic calculations. Phylogenetic calculations were performed with all closest relatives according to BLAST results (data not shown). For clarity, not all of these sequences were included in Figure 2. Phylogeny was inferred using MrBayes version 3.1 [58,59], assuming the GTR (general time reversible) phylogenetic model with 6 substitution rate parameters, a gamma-shaped rate variation with a proportion of invariable sites and default priors of the program. 1,000,000 generations were calculated and sampled every 1000th generation. Burn-in frequency was set to 25% of the samples. The consensus tree was edited in Treeview 1.3 [60].

3.7. Fermentation and Production of Extracts

The fungi were inoculated in 2 L Erlenmeyer flasks containing 750 mL modified Wickerham-medium [61], which consisted of 1% glucose, 0.5% peptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% malt extract, 3% sodium chloride (pH = 6.8). After incubation for 11–20 days at 28 °C in the dark as static cultures, extracts of the fungi were obtained. The mycelium was separated from the culture medium and extracted with ethanol (150 mL). The fermentation broth was extracted with ethyl acetate (400 mL). Both extracts were combined. Alternatively, cells and mycelium were not separated and the culture broth was extracted together with the cells of some cultures using ethyl acetate. After evaporation of the solvents, the powdery residue was reextracted with ethyl acetate (100 mL). The resulting residues were dissolved in 20 mL methanol and subjected to analytical HPLC-DAD-MS.

3.8. Chemical Analysis

UV-spectra of the identified metabolites were obtained on a NanoVue (GE Healthcare). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX500 spectrometer (500 and 125 MHz for 1H and 13C NMR, respectively), using the signals of the residual solvent protons and the solvent carbons as internal references (δH 3.31 ppm and δC 49.0 ppm for methanol-d4). High-resolution mass spectra were acquired on a benchtop time-of-flight spectrometer (MicrOTOF, Bruker Daltonics) with positive electrospray ionization. Analytical reversed phase HPLC-DAD-MS experiments were performed using a C18 column (Phenomenex Onyx Monolithic C18, 100 × 3.00 mm) applying an H2O (A)/MeCN (B) gradient with 0.1% HCOOH added to both solvents (gradient: 0 min 5% B, 4 min 60% B, 6 min 100% B; flow 2 mL/min) on a VWR Hitachi Elite LaChrom system coupled to an ESI-ion trap detector (Esquire 4000, Bruker Daltonics).

Preparative HPLC was carried out using a VWR system consisting of a P110 pump, a P311 UV detector, a smartline 3900 autosampler and a Phenomenex Gemini-NX C18 110A, 100 × 50 mm, column or a Merck Hitachi system consisting of an L-7150 pump, an L-2200 autosampler and an L-2450 diode array detector and a Phenomenex Gemini C18 110A AXIA, 100 × 21.20 mm, column.

For the preparation of cillifuranone (1), the same solvents were used as for the analytical HPLC, with a gradient from 10% B, increasing to 60% B in 17 min, to 100% B from 17 to 22 min. 1 eluted with a retention time of 6.8 min and the amount of 23.2 mg of 1 could be obtained from a culture volume of 10 L.

Properties of cillifuranone (1): pale yellow needles; UV (MeOH) λmax (logɛ) 278 (4.36); for 1D and 2D NMR data see Table 3 and SI; HRESIMS m/z 219.0627 (calcd for C10H12O4Na 219.0628).

3.9. Bioassays

Possible antimicrobial effects of cillifuranone (100 μM) were tested against Bacillus subtilis (DSM 347), Brevibacterium epidermidis (DSM 20660), Dermabacter hominis (DSM 7083), Erwinia amylovora (DSM 50901), Escherichia coli K12 (DSM 498), Pseudomonas fluorescens (NCIMB 10586), Propionibacterium acnes (DSM 1897T), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (DSM 50071), Pseudomonas syringae pv. aptata (DSM 50252), Staphylococcus epidermidis (DSM 20044), Staphylococcus lentus (DSM 6672), Xanthomonas campestris (DSM 2405), Candida albicans (DSM 1386), Phytophthora infestans, and Septoria tritici according to Schneemann et al. [62]. In addition, cytotoxic activity of cillifuranone (50 μM) towards the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 and the human colon adenocarcinom cell line HT29 were performed according to Schneemann et al. [62]. Inhibitory activities of cillifuranone (10 µM) against the enzymes acetylcholinesterase, phosphodiesterase (PDE-4B2), glycogen synthase kinase 3β, protein tyrosin phosphatase 1B, and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase were tested according to Helaly et al. [63].

4. Conclusion

The marine sponge T. aurantium was found to be a valuable source of secondary metabolite producing fungi. In addition to a variety of known substances, several new natural products were found and it is likely that additional ones can be identified during further studies. The antiproliferative active scopularides [25,26] were the first new metabolites from a Scopulariopsis species isolated from T. aurantium. The new cillifuranone (1) is a second example of a natural product produced by a fungal isolate from T. aurantium. Additional compounds were detected of which the chemical structures are not yet described. The application of alternative cultivation methods, which have not been used so far, are expected to further increase the spectrum of produced metabolites of our isolates obtained from T. aurantium.

The combination of morphological criteria and the results of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 fragment sequencing have been proven to be a valuable tool for the identification of fungal isolates. Apart from representatives of genera, which are widely distributed in terrestrial samples and in addition also reported from different sponges, we also identified members of taxa which so far have not been described to be associated with sponges. These strains distantly affiliated to Bartalinia sp. and Votutella sp. and one strain most likely is a new Phoma species.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the BMBF (03F0414B) and by the Ministry of Science, Economic Affairs and Transport of the State of Schleswig-Holstein (Germany) in the frame of the “Future Program for Economy”, which is co-financed by the European Union (EFRE). We are grateful to Rüdiger Stöhr and Tim Staufenberger for sampling the sponge specimens and to Arlette Erhard, Regine Koppe, Katja Kulke, Kerstin Nagel, Andrea Schneider, Susann Malien, and Regine Wicher for their technical assistance. We thank J.B. Speakman from BASF for providing the strains P. infestans and S. tritici as well as for the support in their cultivation. We are grateful to A.W.A.M. de Cock and N.R. de Wilde from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS, Utrecht, Netherlands) for the identification of strain LF064. We thank M.B. Schilhabel (Institute for Clinical Molecular Biology, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany) and his team for sequencing.

We thank G. Kohlmeyer-Yilmaz, M. Höftmann and F. Sönnichsen for running and processing NMR experiments at the Otto-Diels Institute of Organic Chemistry (Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Germany). We also thank U. Drieling (Otto-Diels Institute of Organic Chemistry (Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Germany) for giving us the opportunity and assisting us with the measurement of the optical rotation.

Footnotes

Samples Availability: Available from the authors.

References

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey AL. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blunt JW, Copp BR, Hu WP, Munro MH, Northcote PT, Prinsep MR. Marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:170–244. doi: 10.1039/b805113p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.König GM, Kehraus S, Seibert SF, Abdel-Lateff A, Müller D. Natural products from marine organisms and their associated microbes. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:229–238. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imhoff JF, Stöhr R. Sponge-associated bacteria: General overview and special aspects of bacteria associated with Halichondria panicea. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2003;37:35–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55519-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Z, Li B, Zheng C, Wang G. Molecular detection of fungal communities in the Hawaiian marine sponges Suberites zeteki and Mycale armata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6091–6101. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01315-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siepmann R, Höhnk W. Über Hefen und einige Pilze (Fungi imp., Hyphales) aus dem Nordatlantik. Veröff Inst Meeresforsch Bremerh. 1962;8:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth FJ, Jr, Ahearn DG, Fell JW, Meyers SP, Meyer SA. Ecology and taxonomy of yeasts isolated from various marine substrates. Limnol Oceanogr. 1962;7:178–185. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höhnk U, Höhnk W, Ulken U. Pilze aus marinen Schwämmen. Veröff Inst Meeresforsch Bremerh. 1979;17:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sponga F, Cavaletti L, Lazzaroni A, Borghi A, Ciciliato I, Losi D, Marinelli F. Biodiversity and potentials of marine-derived microorganisms. J Biotechnol. 1999;70:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Höller U, Wright AD, Matthée GF, König GM, Draeger S, Aust HJ, Schulz B. Fungi from marine sponges: Diversity, biological activity and secondary metabolites. Mycol Res. 2000;104:1354–1365. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steffens S. 2003. Prokaryoten und Mikrobielle Eukaryoten aus Marinen Schwämmen. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

- 13.Namikoshi M, Akano K, Kobayashi H, Koike Y, Kitazawa A, Rondonuwu AB, Pratasik SB. Distribution of marine filamentous fungi associated with marine sponges in coral reefs of Palau and Bunaken Island, Indonesia. J Tokyo Univ Fish. 2002;88:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison-Gardiner S. Dominant fungi from Australian coral reefs. Fung Divers. 2002;9:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pivkin MV, Aleshko SA, Krasokhin VB, Khudyakova YV. Fungal assemblages associated with sponges of the southern coast of Sakhalin Island. Russ J Mar Biol. 2006;32:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proksch P, Ebel R, Edrada RA, Riebe F, Liu H, Diesel A, Bayer M, Li X, Lin WH, Grebenyuk V, Müller WEG, Draeger S, Zuccaro A, Schulz B. Sponge-associated fungi and their bioactive compounds: The Suberites case. Bot Mar. 2008;51:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Li Q, Zhu P. Phylogenetic diversity of culturable fungi associated with the Hawaiian sponges Suberites zeteki and Gelliodes fibrosa. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2008;93:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paz Z, Komon-Zelazowska M, Druzhinina IS, Aveskamp MM, Schnaiderman A, Aluma A, Carmeli S, Ilan M, Yarden O. Diversity and potential antifungal properties of fungi associated with a Mediterranean sponge. Fung Divers. 2010;42:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bugni TS, Ireland CM. Marine-derived fungi: A chemically and biologically diverse group of microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:143–163. doi: 10.1039/b301926h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohlmeyer J, Volkmann-Kohlmeyer B. Koralionastetaceae fam. nov. (Ascomycetes) from coral rock. Mycologia. 1987;79:764–778. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amagata T, Minoura K, Numata A. Gymnastatins F–H, cytostatic metabolites from the sponge-derived fungus Gymnascella dankaliensis. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1384–1388. doi: 10.1021/np0600189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiel V, Neulinger SC, Staufenberger T, Schmaljohann R, Imhoff JF. Spatial distribution of sponge-associated bacteria in the Mediterranean sponge Tethya aurantium. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;59:47–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Marine Life. Available online: http://www.european-marine-life.org/02/tethya-aurantium.php (accessed on 15 December 2010).

- 24.Indriani ID. Biodiversity of Marine-Derived Fungi and Identification of their Metabolites. 2007. Ph.D. Thesis, University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany.

- 25.Yu Z, Lang G, Kajahn I, Schmaljohann R, Imhoff JF. Scopularides A and B, cyclodepsipeptides from a marine sponge-derived fungus Scopulariopsis brevicaulis. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1052–1054. doi: 10.1021/np070580e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imhoff JF, Yu Z, Lang G, Wiese J, Kalthoff H, Klose S. Production and use of Antitumoral Cyclodepsipeptide. Patent WO/2009/089810. Jul 23, 2009.

- 27.Ebel R. Secondary Metabolites from Marine-Derived Fungi. In: Proksch P, Müller EG, editors. Frontiers in Marine Biotechnology. Horizon Bioscience; Norfolk, UK: 2006. pp. 73–121. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang G. Diversity and biotechnological potential of the sponge-associated microbial consortia. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maldonado M, Cortadellas N, Trillas MI, Rützler K. Endosymbiotic yeast maternally transmitted in a marine sponge. Biol Bull. 2005;209:94–106. doi: 10.2307/3593127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bringmann G, Lang G, Bruhn T, Schäffler K, Steffens S, Schmaljohann R, Wiese J, Imhoff JF. Sorbifuranones A–C, sorbicillinoid metabolites from Penicillium strains isolated from Mediterranean sponges. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9894–9901. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bünger J, Westphal G, Mönnich A, Hinnendahl B, Hallier E, Müller M. Cytotoxicity of occupationally and environmentally relevant mycotoxins. Toxicology. 2004;202:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SciFinder®. Available online: http://www.cas.org/products/scifindr/index.html (accessed on 13 December 2010).

- 34.Wei MY, Wang CY, Liu QA, Shao CL, She ZG, Lin YC. Five sesquiterpenoids from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. isolated from a gorgonian Dichotella gemmacea. Mar Drugs. 2010;29:941–949. doi: 10.3390/md8040941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochfort S, Ford J, Ovenden S, Wan SS, George S, Wildman H, Tait RM, Meurer-Grimes B, Cox S, Coates J, Rhodes D. A novel aspochalasin with HIV-1 integrase inhibitory activity from Aspergillus flavipes. J Antibiot. 2005;58:279–283. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou GX, Wijeratne EM, Bigelow D, Pierson LS, III, VanEtten HD, Gunatilaka AA. Aspochalasins I, J, and K: Three new cytotoxic cytochalasans of Aspergillus flavipes from the rhizosphere of Ericameria laricifolia of the Sonoran Desert. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:328–332. doi: 10.1021/np030353m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laakso JA, Narske ED, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. Isokotanins A–C: New bicoumarins from the sclerotia of Aspergillus alliaceus. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:128–133. doi: 10.1021/np50103a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Junker B, Walker A, Connors N, Seeley A, Masurekar P, Hesse M. Production of indole diterpenes by Aspergillus alliaceus. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95:919–937. doi: 10.1002/bit.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slack GJ, Puniani E, Frisvad JC, Samson RA, Miller JD. Secondary metabolites from Eurotium species, Aspergillus calidoustus and A. insuetus common in Canadian homes with a review of their chemistry and biological activities. Mycol Res. 2009;113:480–490. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiebe LA, Bjeldanes FF. Fusarin C, a mutagen from Fusarium moniliforme grown on corn. J Food Sci. 1981;46:1424–1426. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maskey RP, Grün-Wollny I, Laatsch H. Sorbicillin analogues and related dimeric compounds from Penicillium notatum. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:865–870. doi: 10.1021/np040137t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buckingham J. Dictionary of Natural Products, Version 191. CRC Press; London, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blunt JW, Munro MH, Laatsch H. AntiMarin Database. University of Canterbury; Christchurch, New Zealand: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niggemann J, Herrmann M, Gerth K, Irschik H, Reichenbach H, Höfle G. Tuscolid and tuscoron A and B: Isolation, structural elucidation and studies on the biosynthesis of novel furan-3(2H)-one-containing metabolites from the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum. Eur J Org Chem. 2004;2004:487–492. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slaughter CJ. The naturally occurring furanones: Formation and function from pheromone to food. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1999;74:259–276. doi: 10.1017/s0006323199005332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White S, O’Callaghan J, Dobson AD. Cloning and molecular characterization of Penicillium expansum genes upregulated under conditions permissive for patulin biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;255:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanokmedhakul S, Kanokmedhakul K, Nasomjai P, Louangsysouphanh S, Soytong K, Isobe M, Kongsaeree P, Prabpai S, Suksamrarn A. Antifungal azaphilones from the fungus Chaetomium cupreum CC 3003. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:891–895. doi: 10.1021/np060051v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorner JW, Cole RJ, Hill R, Wicklow D, Cox RH. Penicillium rubrum and Penicillium biforme, new sources of rugulovasines A and B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:685–687. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.3.685-687.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stierle AA, Stierle DB, Patacini B. The berkeleyamides; amides from the acid lake fungus Penicillum rubrum. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:856–860. doi: 10.1021/np0705054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiozawa H, Takahashi M, Takatsu T, Kinoshita T, Tanzawa K, Hosoya T, Furuya K, Takahashi S, Furihata K, Seto H. Trachyspic acid, a new metabolite produced by Talaromyces trachyspermus, that inhibits tumor cell heparanase: Taxonomy of the producing strain, fermentation, isolation, structural elucidation, and biological activity. J Antibiot. 1995;48:357–362. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuzmanović N. Preliminarna Israživanja Dinamike Vodenih Masa LIMSKOG Kanala (Zavrsni Izvjestaj) Institut Ruder Boskovic; Rovinj, Croatia: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnett HL, Hunter BB. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi. 4th ed. APS Press; St. Paul, MN, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Homepage of MycoBank. Available online: http://www.mycobank.com (accessed on 1 December 2010).

- 54.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall TA. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. Available online: http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html (accessed on 15 April 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. Bayesian analysis of molecular evolution using MrBayes. In: Nielsen R, editor. Statistical Methods in Molecular Evolution. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY, USA: 2005. pp. 183–232. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Page RDM. Treeview: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickerham LJ. Taxonomy of yeasts. US Dep Agr Tech Bull. 1951;29:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schneemann I, Kajahn I, Ohlendorf B, Zinecker H, Erhard A, Nagel K, Wiese J, Imhoff JF. Mayamycin, a cytotoxic polyketide from a marine Streptomyces strain isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria panicea. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1309–1312. doi: 10.1021/np100135b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Helaly S, Schneider K, Nachtigall J, Vikineswary S, Tan GY, Zinecker H, Imhoff JF, Süssmuth RD, Fiedler HP. Gombapyrones, new alpha-pyrone metabolites produced by Streptomyces griseoruber Acta 3662. J. Antibiot. 2009;62:445–452. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]