Abstract

In the early years of the new millennium, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health began funding Oral Health Research Education Grants using the R25 mechanism to promote the application of basic and clinical research findings to clinical training and to encourage students to pursue careers in oral health research. This report describes the impact of an R25 grant awarded to the Texas A&M Health Science Center’s Baylor College of Dentistry (BCD) on its curriculum and faculty development efforts. At BCD, the R25 grant supports a multipronged initiative that employs clinical research as a vehicle for acquainting both students and faculty with the tools of evidence-based dentistry (EBD). New coursework and experiences in all four years of the curriculum plus a variety of faculty development offerings are being used to achieve this goal. Progress on these fronts is reflected in a nascent EBD culture characterized by increasing participation and buy-in by students and faculty. The production of a new generation of dental graduates equipped with the EBD skill set as well as a growing nucleus of faculty members who can model the importance of evidence-based practice is of paramount importance for the future of dentistry.

Keywords: evidence-based dentistry, curriculum, clinical research, faculty development, dental education

For at least two decades, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has been using the R25 mechanism to fund a class of Research Education grants with the varied goals of encouraging student diversity, education in drug abuse and addiction, cancer education, and attracting graduate and postdoctoral students into underrepresented fields of science. The NIH-National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) R25 Oral Health Research Education Grants first offered in the early 2000s sought applications proposing “to strengthen the research component of dental education, to enhance the application of basic and clinical research findings to clinical training, and to encourage both dental school and undergraduate students to pursue careers in oral health research.” The rationale for this initiative lay in the realization that dental curricula often fall short of the goals of incubating critical thinking skills and the ability to integrate scientific discovery into clinical therapeutics, outcomes that are the foundations of lifelong learning and evidence-based practice.1–4 In 2003, the first R25 grant was funded by NIDCR, followed by seven or eight others through 2008. While two symposia provided snapshots of the varied initiatives funded by R25 grants at the American Dental Education Association (ADEA) Annual Session & Exhibition in 2006 and 2010, we felt it important to describe in some detail the impact and transformative power of R25 funding for our institution, Texas A&M Health Science Center’s Baylor College of Dentistry, if others are to use our experience as a guide.

BCD and Its History: The Formation and Eruption of “CUSPID”

Long known for the clinical skills of its graduates, in the early to mid-1990s BCD made important decisions to increase and improve the profile of research and research training at the school and implement a competency-based dental curriculum. In 2004, funding of a U24 Infrastructure Improvement Grant from the NIDCR dramatically increased the number of research faculty members at the college and strengthened a graduate program specifically designed to train dental and craniofacial researchers. The implementation of the competency-based curriculum led to ongoing college-wide self-assessment that early on saw the need to develop cross-cutting competencies centered on professionalism. These competencies stress the importance of training dental students to be lifelong learners and critical thinkers.

In the formation of BCD’s most recent strategic plan (2005–12), the competencies for critical thinking and lifelong learning evolved into a focus on the incorporation of evidence-based dentistry into the curriculum. Our R25 initiative, designated “CUSPID,” is based on the theme that “Clinicians Using Science Produce Inspired Dentists.” CUSPID complements the recent advances at BCD in competency-based education and the development of a strong and sustainable infrastructure for research in the oral health sciences. These research advances include 1) a significant increase in the critical mass of researchers supported by the NIDCR Research Infrastructure Enhancement Program (R24 and U24) awards to BCD; 2) formal collaboration with the University of Texas-Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) in Dallas, a world-class research institution for basic and clinical research; and 3) a comprehensive training program (T32) to develop dental student and faculty researchers for successful dental academic research careers. Collaboration with UTSW is a key part of the T32 grant, but it also includes participation by BCD faculty and students in an NIH Roadmap K12 award for multidisciplinary training of Clinical Research Scholars and a CTSA (Clinical and Translational Science Award, U54) to develop a strong infrastructure for clinical and translational sciences at UTSW and BCD.

Implementing CUSPID and Associated Developments

CUSPID Goals and Organizational Framework

The main thrust of CUSPID is to incorporate critical thinking and formal instruction in evidence-based dentistry into a competency-based curriculum. The principal goals of CUSPID are to 1) create a curricular theme throughout all four years of dental school centered on the knowledge, principles, and skills of scientific inquiry necessary for the dentist to critically evaluate new information and advances in treatment and to participate in dental practice research networks; 2) implement enrichment activities through a Dental Scholars Program that will provide a subset of dental students with additional training and experiences in clinical and translational research; and 3) implement a faculty development program that will enhance the ability of all faculty members to teach students the sound scientific rationale for incorporation of new information and technologies into oral health care.

We chose clinical research as the vehicle for achieving these goals; specifically, we placed a new emphasis in our curriculum on the evaluation and interpretation of clinical research as it relates to practice and development of the skills needed to achieve its integration into clinical dentistry. The rigor and knowledge needed for excellent clinical research, which involves a unique set of skills in epidemiology, biostatistics, and related fields, is often underappreciated by clinicians and dental academicians in both basic science research and clinical teaching areas. Indeed, this underappreciation forms a deep structural problem in biomedical research in the United States and is the rationale for the development of the NIH-National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) roadmap initiatives in developing homes for clinical research through the CTSA initiative. Instruction leading to competence in clinical literature evaluation and synthesis in the context of evidence-based dentistry involves an intersection of clinical skills, scientific knowledge, and critical thinking. For most dental students, this scientific-based competence has the clearest applicability to future practice, where they will continue to exercise these skills as they seek out the newest advances in their field. To reflect the varied and integrative nature of the R25 effort, CUSPID is jointly administered by a team of three principal investigators, each with a unique skill set and academic profile: a basic scientist-educator, a clinician-scientist, and the BCD dean of academic affairs. These choices reflect the intersection in this grant of curriculum, science, and clinical skills.

A New Curricular Theme

The development and implementation of EBD courses and other experiences in each year of the D.D.S. curriculum are central to the EBD initiative at Baylor. In order to focus on each new course or experience, we have chosen to introduce the course-work incrementally, one year at a time (Table 1). Our plan was to lay the foundation in the D1 year and to reinforce this concept in course content presented in subsequent years, increasing the sophistication of its application by our students. In so doing, we wanted the EBD curriculum in successive years to become more small group-driven, with the clinical faculty taking an increasingly prominent role and with EBD becoming integral to clinical instruction and practice.

Table 1.

Curricular resources developed at Baylor College of Dentistry as part of the R25 grant

| Course | Format | Goals | Small Group Focus | Faculty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1: “Fundamentals of EBD and Clinical Research” | Lecture, small groups | Provide foundational knowledge in EBD tools. Fall semester: basic epidemiology; how to assess variation; research design; sampling; confounders and bias. Spring semester: how to read a paper; how to ask a focused clinical question; searching methods; Critically Appraised Topics (CATs). | Assigned articles: small groups are a “lab” in which to practice the skills students are learning in the didactic portion of the course; around 9 students per group discuss a paper on a clinically relevant topic using a standardized format. Sample topics: breast-feeding and caries, fluoride and hip fractures, tobacco use and tooth loss. | Core EBD faculty |

| D2: “Application of EBD I” | Small groups | Maintain student skills at critiquing articles by reading articles that directly relate to preclinical courses in restorative, endo, and pedo; practice writing CATs based on scenarios written by D2 clinical faculty. | Articles and clinical scenarios: article topics include survival of amalgam vs. composites in posterior teeth; effect of taper on crown stability; healing following 1 vs. 2-visit endo. | Core EBD faculty + clinical faculty |

| Each student presents his or her CAT via PowerPoint presentation to the group. | ||||

| All sessions include both a core EBD faculty and clinical faculty member from D2 year. | ||||

| D3: “Application of EBD II” | Treatment planning case conferences | Practice EBD skills in a clinical context. | Clinical dilemmas arising from cases assigned to D3 students. | D3 group leaders |

In fall 2008, a course for first-year dental students entitled “Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Dentistry and Clinical Research” made its debut. This year-long course, which consists of large group lectures/interactive sessions and small group discussions and seminars, has two primary aims: to provide a foundation of knowledge necessary for the effective practice of EBD and to begin to develop the practical skills needed for such practice. Foundational knowledge includes a background in applied clinical epidemiology, biostatistics, and some areas of modern dental and craniofacial research. The development of practical skills emphasizes how to evaluate clinical studies, how to formulate a focused clinical research question, and how to search the dental literature to find and evaluate evidence to answer that question. The didactic portion of the course makes generous use of audience response systems (clickers) to involve students interactively in course content. The small group sessions consist of biweekly meetings of around eight to ten students with one or two faculty members to discuss an assigned paper on a clinically relevant topic, using a standardized article review format. To date, the topics have included breastfeeding and caries, fluoride in water and hip fracture, tobacco use and tooth loss, and fluoride varnish and caries prevention, among others.

In the EBD content developed for D2 students (“Application of Evidence-Based Dentistry I”), each student participates in small group sessions several times per semester to obtain further practice in analyzing clinical research articles. In one session each semester, each student prepares a Critically Appraised Topic (CAT) report based on a clinical scenario written by the BCD clinical faculty and presents this report orally to the group and course faculty. An important feature of this course is the pairing of an EBD core faculty member (typically an instructor in the D1 lecture or small group sessions) with a clinical faculty member for each small group session. This approach has been very successful in providing a clinical perspective on the evidence presented, especially in the CAT.

We anticipate that extension of these experiences into the D3 and D4 years will feature an increasing integration of EBD into coursework and chairside interactions in clinical dentistry. The introduction of EBD into the D3 curriculum, which began in fall 2010, includes integration into case conferences—weekly small group meetings in which students present cases currently under treatment to their group leaders and other students.

Faculty Development: Foundation for Lasting Curricular Change

For our curricular innovations to take hold and flourish, clinical faculty buy-in and support are essential. Yet many, perhaps most, clinical faculty members lack formal training in EBD and have variable degrees of interest in acquiring EBD skills. This is understandable since the training of most faculty members predates the recent and growing interest in EBD within organized dentistry. Furthermore, EBD skills are often strongly associated with difficult and unfamiliar subjects such as statistics and epidemiology. Accordingly, we have adopted a multipronged approach that offers a spectrum of faculty development experiences that seek to accommodate different levels of interest—and stimulate the desire to learn more (Table 2).

Table 2.

Faculty development initiatives conceived as part of the R25 grant at Baylor College of Dentistry

| Activity | Format/Date | Goals | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| For faculty members with uncertain interest | |||

| Retreat focused on engaging the link between basic science and clinical decision making | Faculty retreat, January 2008 | Serve as kickoff for EBD initiative supported by likely funded R25 grant; inform and energize faculty. | EBD updates included at 2009 and 2010 faculty retreats to maintain momentum. |

| Breakfast and lunch meetings with selected clinical faculty members | Small group, June–July 2008 | Target selected clinical faculty members thought to be interested in becoming EBD champions. | Grant-funded “Eat and Learn.” |

| Presentations to clinical departments | Small group, January 2009 | Inform and build interest among key members of Restorative Sciences Department. | At invitation of chair of Restorative Sciences Department. |

| Clinical colloquium | CE-type presentation, began May 2009 | Prior to clinic, update clinical faculty on topics of direct relevance to clinical dentistry; invite clinical experts to present evidence-based talks on controversial topics; lecture followed by Q&A; CE credit awarded. | Attendance for first speaker exceeded all previous records, a trend that has been maintained. Speakers so far have included Jim Summit, Tom Hilton, Chuck Wakefield, and Frank Higginbottom. |

| Research and Scholarship Day | Annual event for which clinics are closed | Enlarge scope of traditional, basic science-focused Research Day to include topics and activities of interest to clinical faculty and D3 and D4 students. | 2009: included clinical case presentations by D3 and D4 students. |

| 2010: added presentations by D2 students on the best of the CATs from fall 2009, as well as a keynote lecture on a clinical research topic by one of our restorative faculty members. | |||

| For faculty members with heightened interest | |||

| Course on fundamentals of EBD for clinical faculty | Small group, summer 2009 and 2010 | Familiarize clinical faculty with the basic tools of EBD (PICO, PubMed searching, fundamentals of statistics, research design, levels of evidence, CATs) in preparation for interacting with students; 9–10 week course, twice per week. | Lectures, but highly interactive with clinical faculty discussions and presentations an important part of the course. |

| EBD workshops and conferences | As pertinent | Provide enrichment experiences for faculty members who are interested in expanding or deepening EBD-related expertise. | R-25 funded attendance at ADA Champions Conference, an EBD workshop in England, and an EBD-based workshop at a national prosthodontics meeting. |

For faculty members with a nascent interest in EBD, we have offered the following opportunities:

EBD information at annual faculty retreats

Our January 2008 faculty retreat, “Engaging the Link Between Basic Science and Clinical Decision Making,” featured presentations designed to inform and generate interest about the soon-to-be-funded R25 grant. Subsequent retreats have featured EBD updates to promote visibility of the initiative. The interest piqued by these events, as well as a series of information-oriented talks to self-selected faculty members or departmental gatherings, has provided the foundation for our next steps in faculty development.

Clinical colloquium

In May 2009, the first in a series of clinical updates on evidence-based topics of interest to the clinical faculty was inaugurated. A total of ninety-one faculty members and residents were in attendance, the largest such gathering of clinical faculty that anyone at BCD can remember. Subsequent seminars have continued to elicit similar attendance by clinical faculty members and residents. With speakers funded by the R25 grant and the provision of continuing education credit, these seminars followed by question-and-answer sessions are intended to stimulate discussion among the clinical faculty on subjects of wide clinical interest, with the hope of increasing familiarity with an evidence-based approach. Topics so far have addressed controversies regarding pulp capping, remineralization of carious lesions, dental adhesives, and osseointegrated implants.

Expanded scope of Research Day

We have expanded the scope of our traditional, basic science-focused Research Day to include topics and activities of interest to the clinical faculty and D3 and D4 students. The reconfigured Research and Scholarship Day program that took place in April 2009 included clinical case presentations by four D3 and four D4 students. In 2010, we added presentations by D2 students of the best of the CATs from fall 2009, as well as a keynote lecture on a clinical research topic by one of our restorative faculty members. These changes increase the visibility of EBD-based efforts and expand the audience to include both students and faculty.

For those clinical faculty members with a previous research background or a desire to learn more about EBD, we have provided the following opportunities for more formal and intensive training:

Summer EBD fundamentals course for clinical faculty

In recognition of the need for EBD champions (clinical faculty members who will carry the EBD effort into the D3 and D4 years), the core EBD faculty created a course that meets twice a week prior to the start of clinic for eight to nine weeks. The intent is to familiarize clinical faculty members with the basic tools of EBD (PICO, PubMed searching, fundamentals of statistics, research design, levels of evidence, CATs) in preparation for interacting with students. Consistent with the principles of adult learning, the course conveys information using a lecture/facilitated-discussion format that is collegial, minimizes jargon, and offers opportunities for hands-on experiences. Six faculty volunteers (most from restorative sciences, general dentistry, and periodontics) “graduated” from the summer 2009 course, and ten more took the summer 2010 course.

Funding for off-campus EBD workshops and conferences

The R25 grant provides funds to support attendance by faculty members (and students) at EBD/critical thinking-themed conferences and workshops. Although curriculum demands sometimes temper enthusiasm and availability for these opportunities (a significant rationale for our in-house EBD course for the clinical faculty), to date the grant has partly or fully funded attendance by BCD faculty members at the American Dental Association (ADA) Champions Conference, an EBD workshop in England, and an EBD-based workshop at a national prosthodontics meeting.

Hope for the Future: The Dental Scholars Track

The remaining thrust of our R25 initiative involves the creation of a track (Dental Scholars) for a few select dental students in each class who express interest and aptitude for a career in patient-oriented research and/or dental academics. This track offers enrichment experiences designed to mirror three primary aspects of a clinician-scholar in an academic position: teacher, researcher, and mentor. Three entering D1 students from the class of 2013 were chosen as the first Dental Scholars based on their interests and background. All three participated in faculty-mentored research projects in summer 2009. Two of the three submitted American Association for Dental Research student research fellowship applications for 2010, one of which was funded. They have also attended BCD seminars featuring speakers on developmental biology of the craniofacial region and craniofacial surgery, preceded by a journal club discussion of one of the speaker’s articles. Activities in ensuing years will include elective courses in teaching and dental academia, attendance at clinical research workshops, participation in an academic fellows program and teaching practicum, and rotations in clinical research. Each Dental Scholar will receive a 25 percent reduction in tuition for years D2–D4 and will be afforded special recognition as a Graduate with Honors in Scholarship at the graduation ceremony.

The Dental Scholars program has been included in a short presentation given to all D.D.S. interviewees, and a flier outlining the program is now included in a mailing to all accepted students. We anticipate selecting more Dental Scholars from subsequent classes, starting with the class of 2014, to build a cohort of like-minded students.

Outcomes to Date

As befits an evidence-based initiative, proof that our efforts are productive can only be obtained via the gathering of evidence, i.e., outcomes data. The process of institutional improvement has long been central to the culture of BCD. Thus, even though our EBD initiative is only two years old, we have documented some encouraging outcomes and trends that suggest we are on the way to creating an EBD culture. Some highlights are as follows:

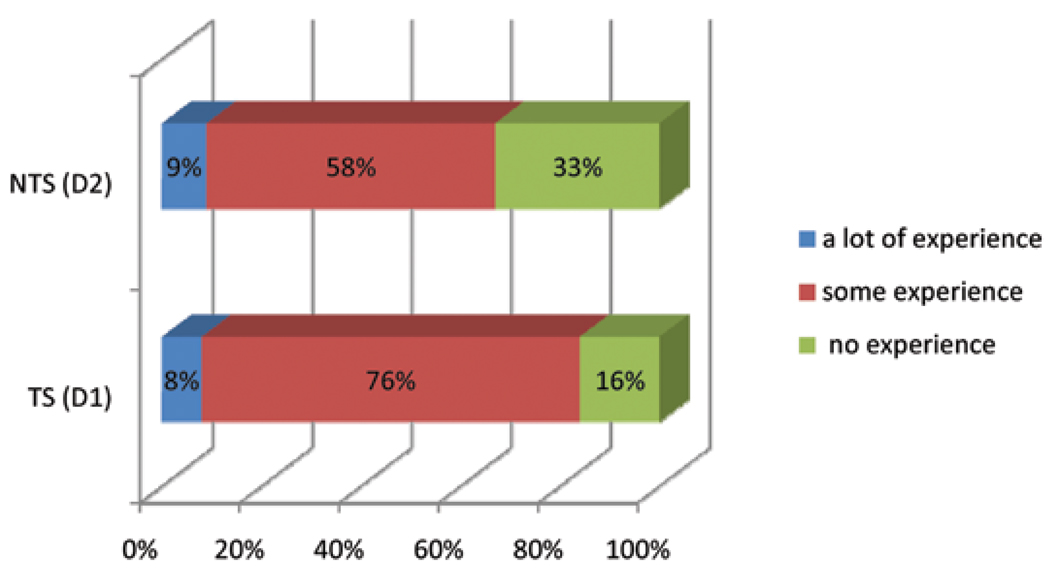

Our EBD curriculum stimulates interest in research and academic careers in students

Using a survey instrument that assessed practices, experience, attitudes, and knowledge about EBD, we were able to document the following for students and faculty: the participant’s habitual information sources, experience in reading and evaluating the dental literature, research and related activities, attitudes about EBD and interest in clinical/translational research, and EBD knowledge based on analysis of a short research report. The survey was administered to D1 and D2 students in spring 2009 near the end of the first academic year of the program’s introduction. Thus, the D2 students constituted a completely EBD-naïve sample, and the D1 students constituted a sample with almost a year of EBD instruction. The survey5 revealed that the trained D1 students (TS) were more likely to read dental and medical journals (p<0.001) and reported more confidence in evaluating research reports (p<0.001) and more experience using evidence from the professional literature to form conclusions (p<0.05) than the untrained D2 students (Figures 1–3). The trained students were also more interested in learning about research careers (p<0.05) and teaching p<0.001) than the untrained D2 students (Figure 4). These students were more supportive of EBD principles (p<0.01) and believed that it had changed the way they read clinical articles (p<0.001) (Figure 5). Not surprisingly, they exhibited higher scores (p<0.001) on the knowledge portion of the test. We will follow these students as they progress through the curriculum to determine whether these trends continue or become more pronounced. Despite the pedagogical contrast presented by the interactive/critical thinking EBD course with the more traditional biomedical sciences of the D1 year, student reviews of the D1 EBD course indicate an appreciation for the applicability of the skill set being taught (even if the statistics side of it is not appreciated!) as well as the small group sessions that encourage them to work in teams to review articles. The D2 EBD course, which is entirely small group-based, is regarded even more highly.

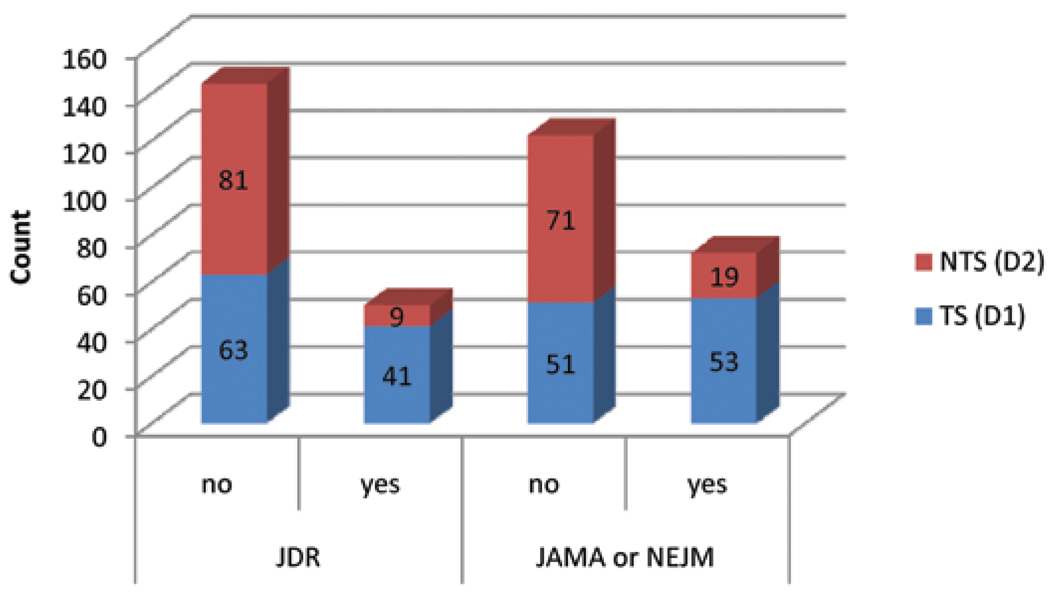

Figure 1. Number of EBD-non-trained (NTS) and EBD-trained (TS) students who reported that they read or had read the Journal of Dental Research (JDR), Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), or New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Note: TS=104 students, NTS=90 students. Differences between TS and NTS are significant at p<0.001 (chi-square).

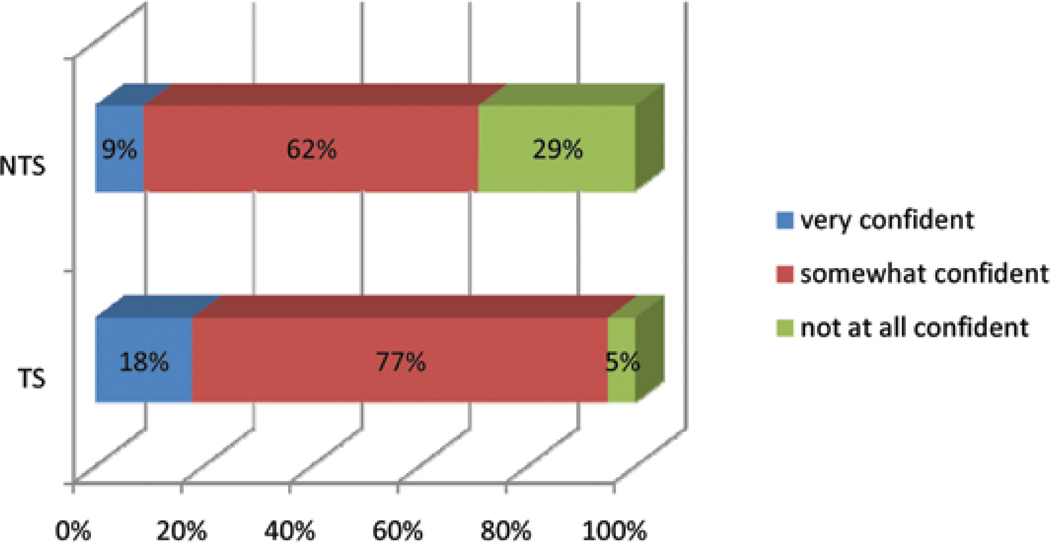

Figure 3. Level of confidence in evaluating research reports among EBD-non-trained (NTS) and EBD-trained (TS) students.

Note: Differences between TS and NTS are significant at p<0.001 (Mann-Whitney U).

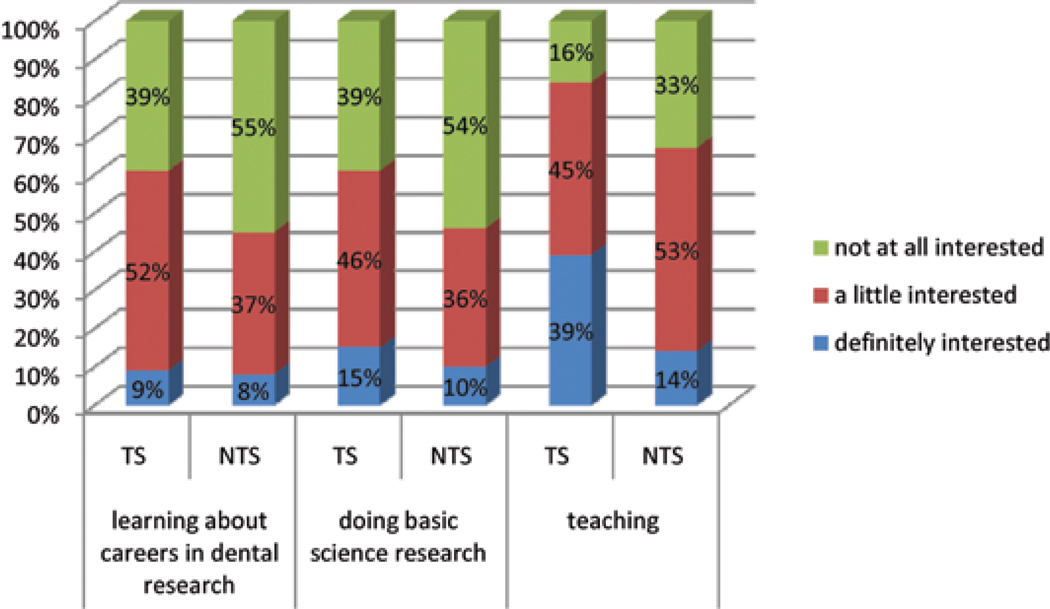

Figure 4. Level of interest indicated by EBD-non-trained (NTS) and EBD-trained (TS) students in learning about dental (clinical) research, doing basic science research, and teaching.

Note: Differences between TS and NTS are significant at p<0.046 for dental research, p<0.049 for basic science research, and p<0.001 for teaching.

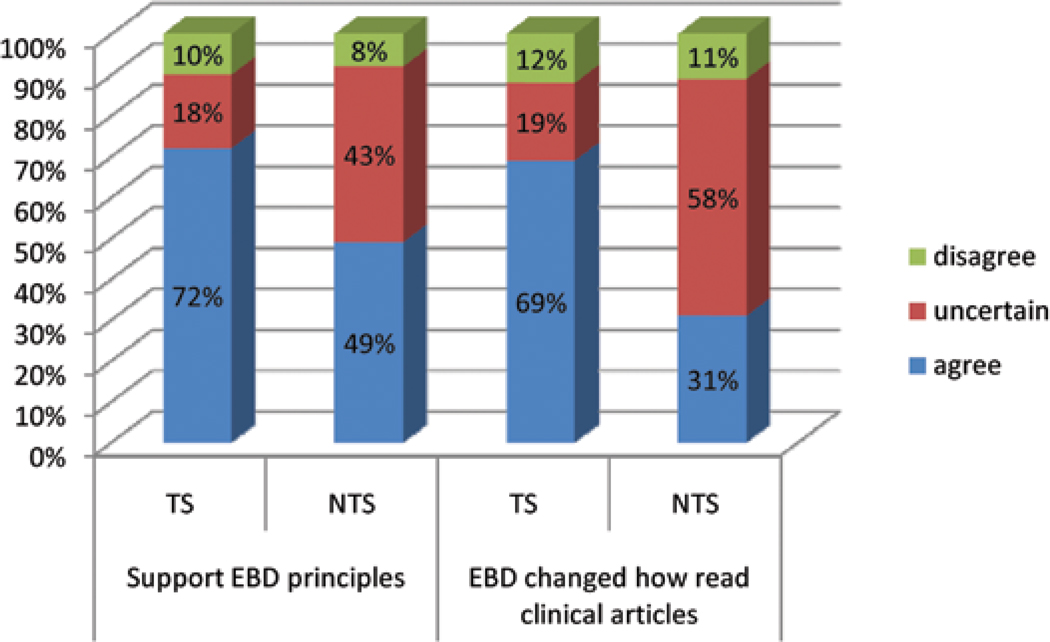

Figure 5. Levels of support for EBD principles and extent to which EBD changed how they read an article: responses among EBD-non-trained (NTS) and EBD-trained (TS) students.

Note: Differences between TS and NTS are significant at p<0.011 for EBD principles and p<0.001 for how they read articles.

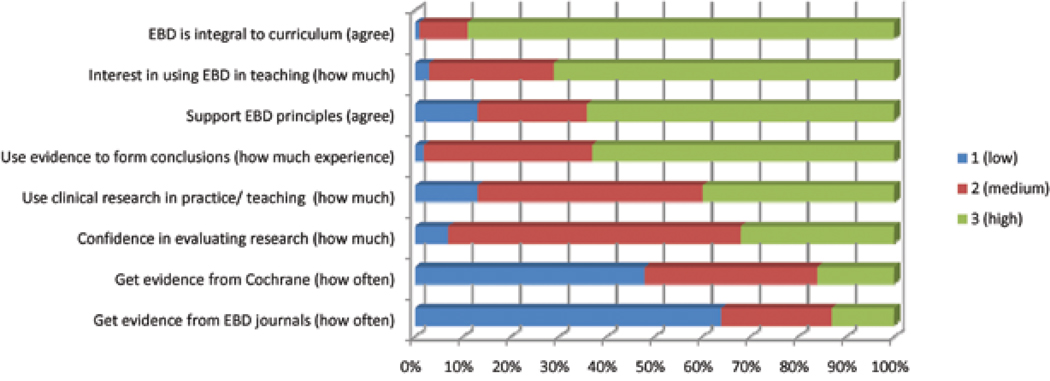

Faculty development efforts have energized subsets of the clinical faculty

Using a modified version of the same assessment instrument, all faculty members with 50 percent FTE or greater were surveyed in spring 2009. The results of this survey (based on 62/142 faculty members) constitute a baseline level of knowledge and opinions regarding EBD against which subsequent progress can be measured. While the majority of faculty respondents expressed support for EBD principles and their inclusion in the curriculum, a considerably smaller cohort indicated a high level of confidence in actually using EBD in their teaching or practice (Figure 6). On the EBD knowledge test, the faculty respondents performed similarly to the trained D1 students (p>0.50).

Figure 6. Distribution of faculty responses to questions about EBD attitudes and practices: responses reflect low, medium, or high levels of interest or enthusiasm for each statement.

Beyond these quantitative results, we are encouraged by the willingness of a core group, mostly comprised of restorative (D3) and general dentistry (D4) faculty members, to acquire EBD tools via the summer course for clinical faculty, thereby stepping forward as champions of the EBD effort. In a focus group conducted following the course, participants indicated that they particularly appreciated the interactive features such as the opportunity to present and discuss their PICOs and CATs. Encouragingly, they spoke of a new realization about the nature and use of evidence; to quote one participant: “I will no longer use the phrase ‘That’s the way I always do it.’” Already, one of our 2009 “graduates” has begun organizing EBD tutorials for faculty members in her department who are interested but unable to attend the summer course. We are also starting to build our own experts: a faculty member with epidemiology training attended the 2010 ADA Evidence Reviewer Program, a workshop in which participants learn to critically appraise systematic reviews. The attendance and informal feedback from faculty members regarding our Clinical Colloquium speakers have been very gratifying, and the colloquium is starting to have its intended effect: knowledge transfer that also heightens appreciation for the importance of evidence in clinical decision making. Finally, the increased collegiality between basic science and clinical faculty members engendered by the EBD initiative has facilitated other curricular efforts. For example, a newly inaugurated Integrative Sciences course in the D2 year, which requires the construction of case-based scenarios based on all first-year disciplines (basic science and preclinical), is drawing on the experience of the R25 initiative and will lead to a future integration of the evaluation of cases that include both EBD principles and an application of basic biomedical science.

The Dental Scholars track, although just begun, shows great promise

Although the Dental Scholars track is in some sense the least important initiative in terms of the overall goal of the grant, its potential for incubating future dental faculty members and clinical researchers is exciting. One option available to each scholar is continuing involvement with his or her clinical research project throughout dental school. This continuing research exposure via an ongoing preceptorship and lab affiliation provides for continuation of an experience that did not previously extend beyond the D2 year, as well as affording the scholar an opportunity to mentor other D.D.S. students or a more junior scholar in the lab. Once the teaching elective has been completed, an alternative option is to conduct an education-related research project that can be presented at an ADEA meeting and at Research and Scholarship Day. We believe that a teaching internship is an important part of the process of attracting future dental faculty members, as studies have found that the opportunity to teach has been an important factor encouraging interest in an academic career.6–8 We are tracking participation in this dual track to evaluate its success in persuading some bright dental graduates of the rewards of a career in dental research and academics.

Synergy and Collateral Possibilities: It’s All Good

The aims of this grant, if achieved, will result in a graduating dentist who is better equipped to analyze and filter the massive amount of information to which he or she will be subjected and to decide whether and/or how to incorporate this information into the treatment of patients. In addition, the training of dental school faculty members in the principles and practices of EBD will enrich them professionally while enabling them to serve as role models for students. Finally, providing a clinical/translational research-based track may induce a small subset of D.D.S. students to enter into academic dentistry and/or clinical research.

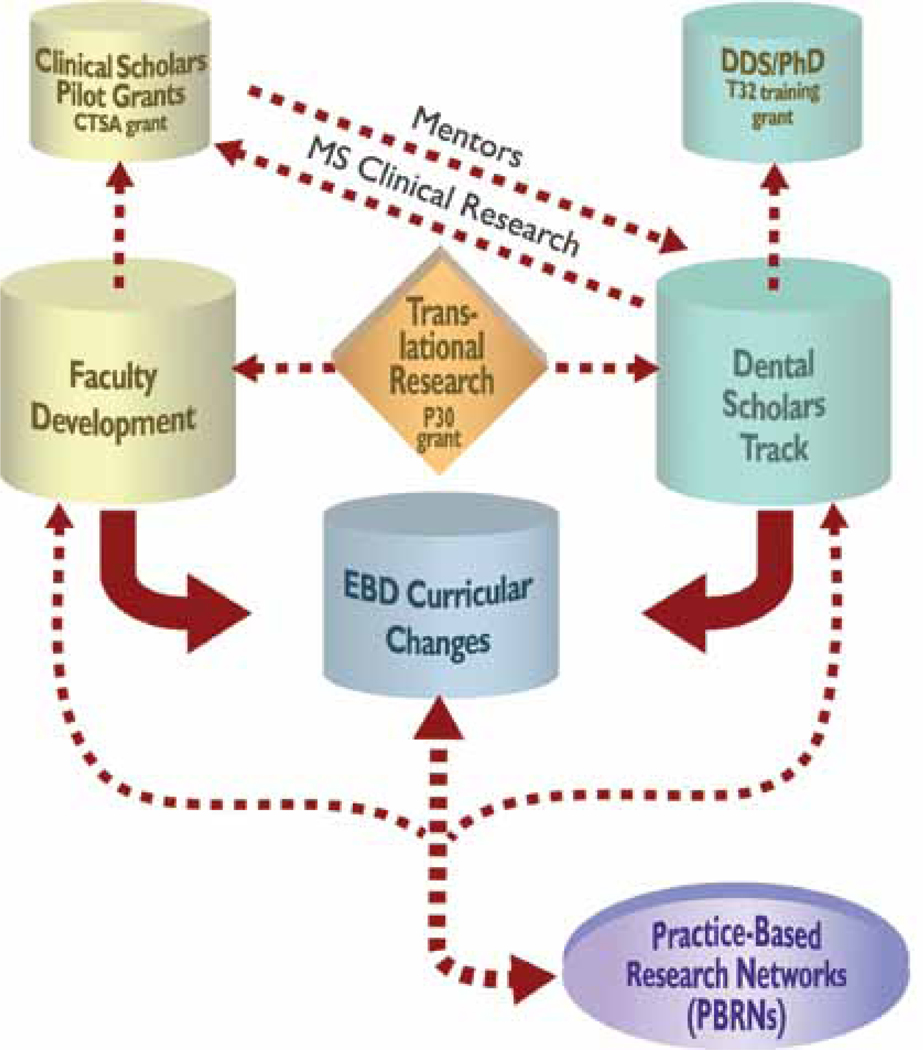

An underappreciated aspect of the R25 mechanism is the impact, sometimes in unanticipated ways, on other efforts within the institution; this too can be culture-changing. While the faculty development efforts and the Dental Scholars track support and reinforce the EBD curricular changes, we expect that each will generate collateral effects of its own (Figure 7). For example, we are encouraging participants in the Dental Scholars track to apply to study for an M.S. in Clinical Research at UTSW (a part of our CTSA agreement) or alternately continue on to earn a Ph.D. via our T32 training grant. Similarly, we anticipate that some faculty members will follow two of their peers and enter the Clinical Scholars program at UTSW or apply for seed grants for translational research projects. The recent funding of a P30 grant at BCD focused on expanding translational research through the integration of mineralized tissue research, bioengineering, and clinical research approaches not only provides mentors for upcoming Dental Scholars but provides resources for the development of new ideas in clinical and translational research.

Figure 7. Interactive effects of R25-sponsored programs with other existing and planned BCD research and training-based initiatives and programs.

It is realistic to predict that the educational approaches utilized at BCD through its R25 award can also be applied to better engage the practicing community of dental clinicians. Such an application can facilitate the linking of practicing clinicians with a core of academically based clinical and health sciences researchers through a Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN). Currently NIDCR supports three dental PBRNs whose participants are engaged in approximately thirty studies. Thus far, data from these studies have alerted the dental academic research community to the types of studies valued by practitioners. EBD instruction provided to established private sector dentists will improve how clinical evidence is used to inform treatment decisions that improve the daily care of patients (Figure 7). In turn, the integration of EBD instruction into PBRN activities for practicing clinicians will provide an additional educational resource for dental students, providing insight into successful real-world study design and subject enrollment protocols and whetting their interest as future PBRN participants.

Figure 2. Experience level of EBD-non-trained (NTS) and EBD-trained (TS) students who reported that they had no/some/a lot of experience using the evidence in the professional literature to form conclusions.

Note: Differences between TS and NTS are significant at p<0.039 (Mann-Whitney U).

Acknowledgments

While the authors of this article are all faculty members who have been integral to the development of materials and programs to date, a schoolwide effort such as this could not proceed without the efforts of many others. In particular, we would like to extend our appreciation to the following: our dean, Dr. James S. Cole, for his support and encouragement before and after funding; Drs. Lavern Holyfield and David Nunez for the Clinical Colloquium, Drs. Charles Berry and Amp Miller for curricular “magic,” and Dr. Robert Spears for the Dental Scholars and Research Day initiatives; Drs. Steve Karbowski and Mohsen Taleghani for leadership in pivotal departments; and Ms. Jeanne Santa Cruz and Mr. Richard Cardenas for facilitating all of the above. The work described herein was funded by NIH-NIDCR grant DE018883 (to RJH and DLJ).

This project was supported by NIH-NIDCR grant DE018883 (to RJH and DLJ).

Contributor Information

Robert J. Hinton, Regents Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Paul C. Dechow, Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Hoda Abdellatif, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Sciences, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Daniel L. Jones, Professor and Chair, Department of Public Health Sciences, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Ann L. McCann, Associate Professor and Director of Assessment, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Emet D. Schneiderman, Associate Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

Rena D’Souza, Professor and Chair, Department of Biomedical, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M Health Science Center

REFERENCES

- 1.Tedesco LA. Issues in dental curriculum development and change. J Dent Educ. 1995;59(1):97–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolami CN. The role and importance of research and scholarship in dental education and practice. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(8):918–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalkwarf KL, Haden NK, Valachovic RW. ADEA Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(10):1085–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendricson WD, Andrieu SC, Chadwick DG, Chmar JE, Cole JR, George MC, et al. Educational strategies associated with development of problem-solving, critical thinking, and self-directed learning. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(9):925–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann AL, Hinton RJ, Jones DL. J Dent Res. Barcelona meeting of the IADR; 2010. [Accessed: August 24, 2010]. Creating an EBD culture through curricular innovation and faculty training. abstract #2003, At: http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2010barce/webprogramcd/Paper132429.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bibb CA, Lefever KH. Mentoring future dental educators through an apprentice teaching experience. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(6):703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rupp JK, Jones DL, Seale NS. Dental students’ knowledge about careers in academic dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(10):1051–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenkein HA, Best AM. Factors considered by new faculty in their decision to choose careers in academic dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(9):832–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]