Abstract

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a movement disorder with prominent tau neuropathology. Brain diseases with abnormal tau deposits are called tauopathies, the most common being Alzheimer’s disease. Environmental causes of tauopathies include repetitive head trauma associated with some sports. To identify common genetic variation contributing to risk for tauopathies, we carried out a genome-wide association study of 1,114 PSP cases and 3,247 controls (Stage 1) followed up by a second stage where 1,051 cases and 3,560 controls were genotyped for Stage 1 SNPs that yielded P ≤ 10−3. We found significant novel signals (P < 5 × 10−8) associated with PSP risk at STX6, EIF2AK3, and MOBP. We confirmed two independent variants in MAPT affecting risk for PSP, one of which influences MAPT brain expression. The genes implicated encode proteins for vesicle-membrane fusion at the Golgi-endosomal interface, for the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response, and for a myelin structural component.

PSP is a rare neurodegenerative movement disorder clinically characterized by falls, axial rigidity, vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, bradykinesia, and cognitive decline. Though PSP is rare (prevalence is 3.1–6.5/100,0001), after Parkinson’s disease (PD), PSP is the second most common cause of degenerative parkinsonism2. PSP is a tauopathy with abnormal accumulation of tau protein within neurons as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), primarily in the basal ganglia, diencephalon, and brainstem, with neuronal loss in globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra. Abnormal tau also accumulates within oligodendroglia and astrocytes3. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), even though all cases have NFTs, Aβ plaques are closely tied to the primary disease process, and thus AD is a secondary tauopathy. PSP is a primary tauopathy because tau is the major abnormal protein observed. Both environmental insults and inherited factors contribute to the risk of developing tauopathies4. Repetitive brain trauma, associated with certain sports, can cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy associated with tau deposits5. Viral encephalitis, associated with subsequent parkinsonism, is also associated with tau neuropathology. In PSP, neurotoxins4 and low education levels6 may also contribute to risk. Genetic risk for PSP is in part determined by variants at a 1 Mb inversion polymorphism that contains a number of genes including MAPT, the gene that encodes tau7. The inversion variants are called H1 and H2 “haplotypes”, with H1 conferring risk for PSP8. H1 also contributes to risk for corticobasal degeneration9,10 and Guam amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism dementia complex11, both rare tauopathies. H1 does not contribute to risk for AD. Surprisingly, H1 is also a risk factor for PD12, a movement disorder with clinical features that overlap those of PSP, yet in PD there are no neuropathologically recognizable tau containing lesions.

We performed a genome wide association (GWA) study of PSP to identify genes that modify risk for this primary tauopathy. We performed a two-stage analysis to maximize efficiency while maintaining power13,14. For Stage 1 we used only autopsied cases (n = 1,114), thereby essentially eliminating incorrect diagnoses. These were contrasted with 3,287 controls; 96% of cases and 90% of controls were of European ancestry (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). We assessed association between genotypes at 531,451 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and PSP status among subjects of all ancestries (Supplementary Table 2) and those of only European ancestry (Table 2) using an additive model. Results from both ancestry groups were similar. Because our control samples were younger than cases, we compared their allele frequencies at significant and strongly suggestive SNPs to those of older controls (N = 3,816) from three datasets from the NIH repository Database for Genotypes and Phenotypes (Supplementary Table 3). Only SNPs with no significant differences in allele frequencies between old and young controls are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the samplesa

| Cohort | Total sample analyzed |

Gender (male) | Onset Age | Age-at-death | Disease Duration | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | nb | Mean age |

Range | SD (±) |

n | Mean age |

range | SD (±) |

n | Mean duration (years) |

range | SD (±) |

n | ||

| PSP stage 1c | 1,114 | 55 | 599 | 68 | (41–93) | 8.2 | 827 | 75 | 45–99 | 8.0 | 1,070 | 7.4 | 1–21 | 3.2 | 827 |

| PSP stage 1 European Ancestry | 1,069 | 55 | 570 | 68 | (41–93) | 8.3 | 794 | 75 | 45–99 | 8.0 | 1,025 | 7.4 | 1–21 | 3.1 | 794 |

| PSP stage 2d | 1,051 | 53 | 530 | 65 | (40–91) | 7.3 | 913 | 75 | 57–94 | 7.4 | 118 | 8.0 | <1–18 | 3.3 | 42 |

Controls were young normal subjects recruited from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Health Care Network (See Online Methods for details). These were 3,287 controls for Stage 1 and 3,560 for Stage 2;

n, number of samples with available data. Values of n for each type of analysis do not add up to the total samples used because of missing values;

Stage 1 consisted of autopsy-confirmed cases.

The stage 2 dataset included 130 cases with autopsies. All stage 2 samples (cases and controls) were independent of stage 1 samples.

Table 2.

Results from Stage 1, Stage 2, and joint analysis among subjects of European Ancestry: SNPs Significant at P < 5 × 10−8 in the joint analysis

| Chr band | SNP Location (bp) |

Gene or nearby gene |

Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Joint P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAFa Case |

MAF Contb |

ORc/CI | P1 | MAF Case |

MAF Cont |

OR / CI | P2 | OR/CI | PJ | |||

| 1q25.3 | rs1411478 179,229,155 |

STX6 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.73 0.65 – 0.81 |

1.8 × 10−9 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.85 0.77 – 0.94 |

1.5 × 10−3 | 0.79 0.74 – 0.85 |

2.3 × 10−10 |

| 2p11.2 | rs7571971 88,676,716 |

EIF2AK3 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.75 0.66 – 0.84 |

7.4 × 10−7 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.75 0.67 – 0.83 |

8.7 × 10−8 | 0.75 0.69 – 0.81 |

3.2 × 10−13 |

| 3p22.1 | rs1768208 39,498,257 |

MOBP | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.70 0.63 – 0.79 |

10 × 10−10 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.74 0.67 – 0.82 |

1.3 × 10−8 | 0.72 0.67 – 0.78 |

1.0 × 10−16 |

| 17q21.31 | rs8070723 41,436,651 |

MAPT | 0.05 | 0.23 | 5.50 4.40 – 6.86 |

2.1 × 10−51 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 4.74 3.92 – 5.74 |

4.8 × 10−67 | 5.46 4.72 – 6.31 |

1.5 × 10−116 |

| rs242557 41,375,823 |

MAPT | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.48 0.43 – 0.53 |

2.2 × 10−37 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.54 0.48 – 0.59 |

5.0 × 10−35 | 0.51 0.47 – 0.55 |

4.2 × 10−70 | |

|

crs242557/ rs8070723 |

MAPT | --- | --- | 0.66 0.58 – 0.74 |

1.3 × 10−11 | --- | --- | 0.74 0.67 – 0.83 |

6.3 × 10−8 | 0.70 0.65 – 0.76 |

9.5 × 10−18 | |

MAF, minor allele frequency;

OR based on major allele,

rs242557 controlling for rs8070723;

Abbreviations and gene symbols: P1, stage 1 P value; P2, stage 2 P value; PJ, joint P value; STX6, syntaxin 6; EIF2AK3, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-α kinase 3; MOBP, myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein; MAPT, microtubule associated protein tau; a summary of the function of each gene listed is in Supplementary Table 9. Associations were determined using an additive genetic model. Exploratory analyses (results not shown) of PSP using dominant and recessive models did not produce new loci although some of the associations in 17q21.31 were also consistent with these non-additive models. These less parsimonious models did not fit the data significantly better than the additive model. By evaluating 5000 SNPs with the smallest P-values in more complicated models involving main effects and interactions38, no noteworthy gene-gene interactions were uncovered. There were additional SNPs in the regions for the above loci that were significant or strongly suggestive for association; however, they were no longer significant after controlling the most significant SNP in the region (Supplementary Table 5). All loci significant in the joint analyses remained so after controlling for the MAPT inversion (Supplementary Table 10).

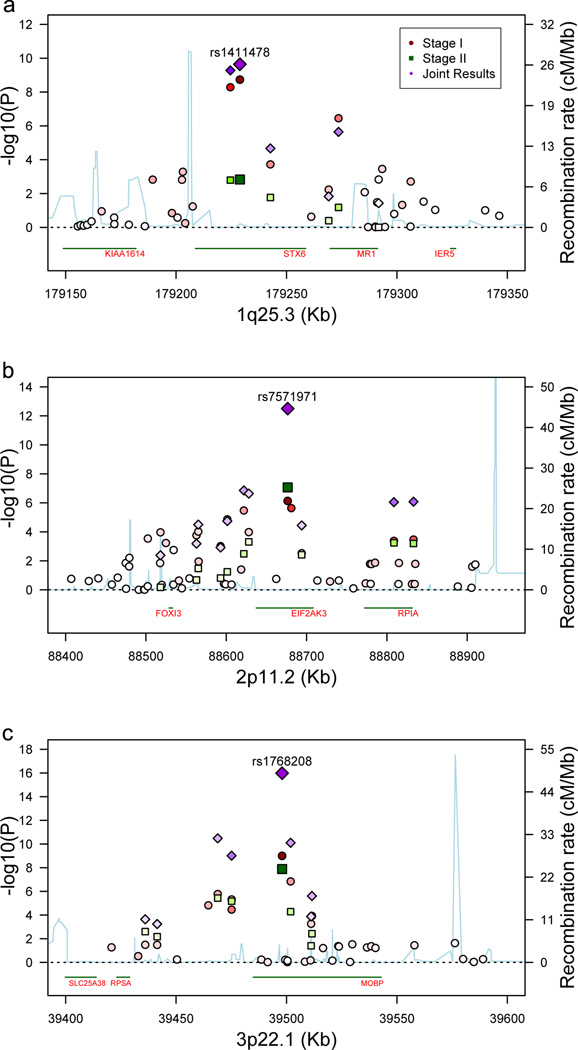

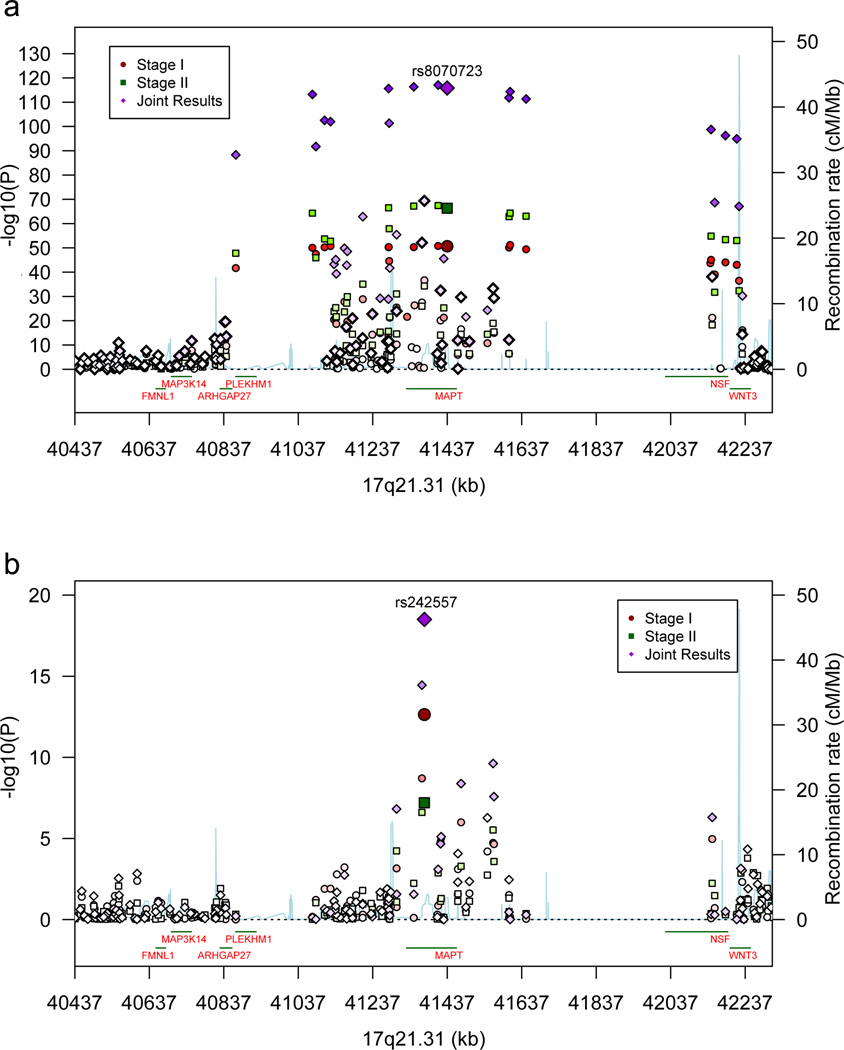

Stage 1 P-values (P1) for SNPs in three regions crossed the significance threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 (Table 2, Fig. 1). At 1q25.3, a SNP in STX6 crossed this threshold (P1 = 1.8 × 10−9). Another SNP at 3p22.1 in MOBP crosses this threshold (P1 = 1.0 × 10−9). The third region was 17q21.31, in which 58 SNPs had P1 < 5 × 10−8 (Table 2, Fig. 2a). This focus of association is the approximately 1 Mb H1/H2 inversion polymorphism containing MAPT15.

Figure 1.

(a) Association results for 1q25.3 STX6. (b) Association results for 2p11.2 EIF2AK3. (c) Association results for 3p22.1 MOBP regions. –log10 P values are shown for Stages 1 and 2 and the joint analyses. Recombination rate, calculated from the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of the region, is derived from Hapmap3 data. LD, encoded by intensity of the colors, is the pairwise LD of the most highly associated SNP at Stage 1 with each of the SNPs in the region. Transcript positions are shown below each graph.

Figure 2.

(a) Association results for the 17q21.31 H1/H2 inversion polymorphism (40,974,015 – 41,926,692 Kb) and flanking segments. (b) Association results for 17q21.31 controlling for H1/H2. Results are shown for Stages 1 and 2 and the joint analyses. Recombination rate, calculated from the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of the region, is derived from Hapmap3 data. LD, encoded by intensity of the colors, is the pairwise LD of the most highly associated SNP at Stage 1 with each of the SNPs in the region.

SNPs for Stage 2 were selected from the original set if they yielded a P1 < 10−3. We assessed 4,099 SNPs for association in 1,051 cases, mostly living subjects clinically diagnosed with PSP (Supplementary Table 4) and 3,560 control subjects, all of European ancestry. We also included 197 ancestry informative markers16 to evaluate population substructure. Clinically diagnosed PSP17 is reasonably concordant with autopsy results18. We estimated the diagnostic misclassification rate as 12%, which has only a small impact on power (Online Methods).

All three loci associated in Stage 1, were replicated by joint analysis (Table 2, Figs. 1 and 2). Joint analysis revealed two new loci with joint P-values (PJ) below the genome-wide significant threshold. One was at 2p11.2, within EIF2AK3 (PJ = 3.2 × 10−13). Another, rs12203592 (PJ = 6.2 × 10−15), at 6p25.3, highlighted IRF4, with a neighboring SNP in EXOC2, rs2493013 (PJ = 6.0 × 10−7); rs2493013 was significant after controlling for rs12203592 at P < 1 × 10−3 (Supplementary Table 5). However, allele frequencies for rs12203592 and rs2493013 in older controls were significantly different from those of our controls (Supplementary Table 3). Curiously, the older control data sets were all significantly different from each other. While rs12203592 alleles frequencies vary widely across Europe19, we could not ascribe these fluctuations amongst controls to either ancestry or genotyping artifacts. In the joint analysis, 3 other loci reached suggestive association (an intergenic region at 1q41, PJ = 2.8 × 10−7; BMS1, PJ = 4.9 × 10−7; SLCO1A2, PJ = 1.9 × 10−7; Supplementary Table 6 and Figure 5).

In the MAPT region, most of the PSP-associated SNPs mapped directly or closely onto H1/H2, producing very small P-values (e.g., for rs8070723, P1 = 2.1 × 10−51, PJ = 1.5 × 10−116). H1 confers risk and 95% of PSP subject chromosomes are H1 compared to 77.5% of control chromosomes. In the Stage 1 autopsy cases, the odds ratio (OR) is 5.5 [confidence interval (C.I.) 4.4 – 6.86, Table 2], which is stronger than the OR for the APOE ε3/ε4 genotype as a risk locus for AD20. The OR for the Stage 2 PSP samples was comparable to the Stage 1 OR, evidence that the clinically and autopsy-diagnosed cohorts are similar in composition.

If all of the risk from 17q21.31 were associated with H1/H2, controlling for H1/H2 (using rs8070723 as a proxy) should be sufficient to make association at all other loci in this region non-significant. That is not the case; instead certain SNPs remained associated, with the maximum falling in MAPT (rs242557) (Table 2, Figure 2, Supplementary Table 5). No other 17q21.31 SNPs showed association after controlling for rs8070723 and rs242557 genotypes. SNP rs242557 was previously identified as a key regulatory polymorphism influencing MAPT expression21. Note that rs242557 accounts for only part of the total risk associated with H1/H2 (Table 2).

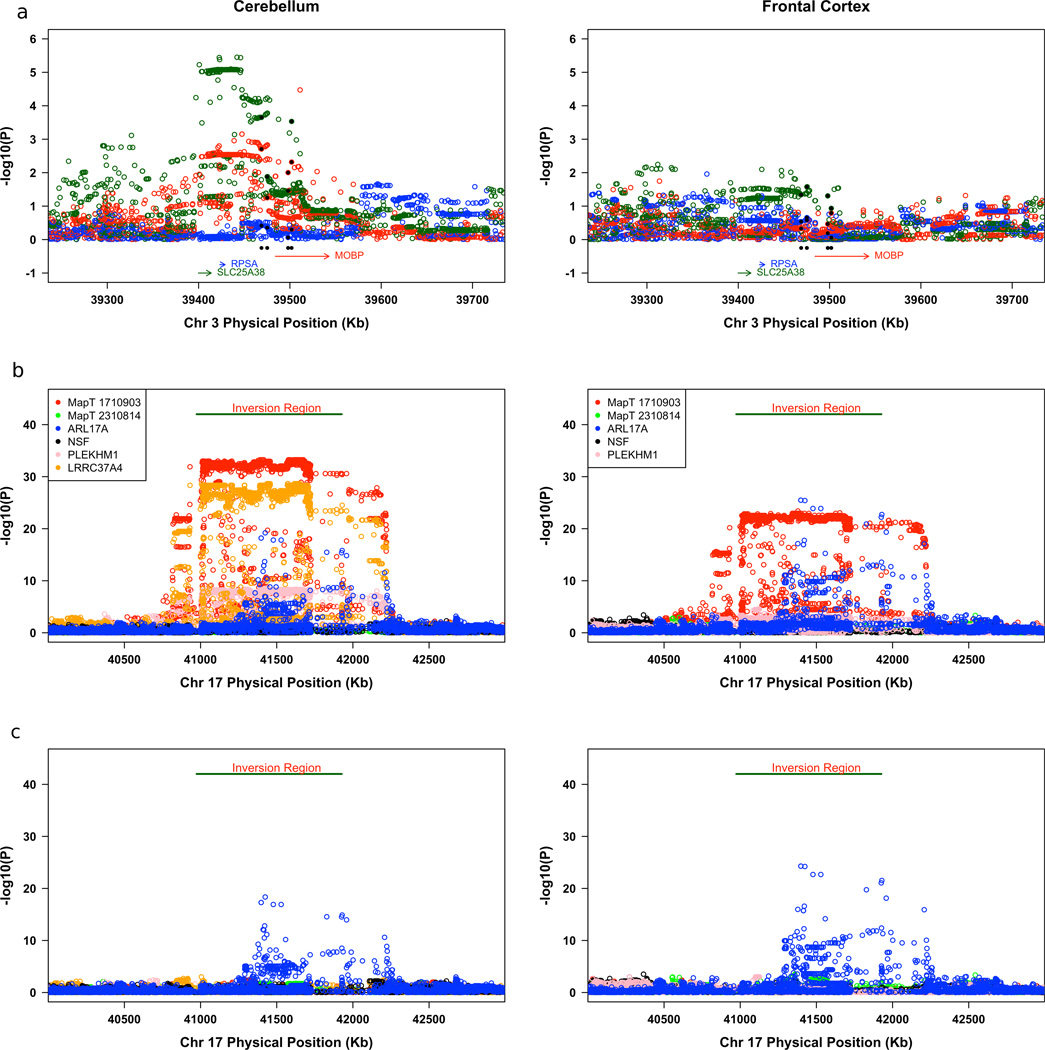

The SNPs used to detect a GWA signal are not necessarily the risk-causing variants. For STX6 and EIF2AK3, there are non-synonymous SNPs in close proximity to and highly correlated with the top GWA SNPs (Supplementary Table 7) making these coding changes candidates for the pathogenic change. To evaluate the possibility that some risk-variants regulate gene expression, we analyzed the correlations between gene expression levels from two brain regions of 387 normal subjects and SNP genotypes for the regions listed in Table 2. Two regions showed strong genotype-expression associations (Fig. 3). SNPs falling in or near MOBP have some effect on MOBP expression, but are more strongly correlated with SLC25A38 expression, which is 70 kb from MOBP (Fig. 3a). This effect on SLC25A38 is seen in cerebellum but is weaker in the frontal cortex.

Figure 3.

(a) Association results for the relationship between SNP genotypes and mRNA transcripts from the cerebellum and frontal cortex for the SLC25S38/MOBP region. (b) Association results for the relationship between SNP genotypes and mRNA transcripts from the cerebellum and frontal cortex for the H1/H2 inversion polymorphism region. (c) Association results for the relationship between SNP genotypes and mRNA transcripts from the cerebellum and frontal cortex for the H1/H2 inversion polymorphism region controlling for H1/H2. The color of the circle corresponds to the color assigned each gene and each SNP is tested against multiple cis transcripts. The data presented here are independent samples from those used previously by Simon-Sanchez et al.12.

The second region showing a strong genotype-expression correlation is the MAPT inversion region. SNP alleles across the entire H1/H2 inversion and flanking regions show strong correlation with not only MAPT expression (p = 8.71 × 10−28 for multiple SNPs), but also with ARL17A (P = 9.2 × 10−22), PLEKHM1 (P = 1.0 × 10−9), and LRRC37A4 (P = 2.2 × 10−35)12. Note that while MAPT expression is correlated with SNPs across the entire inversion region, the SNPs influencing ARL17A are associated with a subset of regional SNPs and these are not identical to the SNPs affecting MAPT expression. Expression of CRHR1 and KIAA1267, genes that are in the inversion region and that flank MAPT, is not correlated with H1/H2 SNPs.

To distinguish between the effects on gene expression of the inversion versus other independent effects, we controlled for H1/H2 as was done for association with PSP (Table 2). After controlling for H1/H2, all significant genotype-expression correlation for MAPT and LRRC37A4 disappears (Fig. 3c) showing that either the orientation of this region or a polymorphism that maps onto H1/H2, determines MAPT expression. In contrast, controlling for H1/H2 has no effect on genotype-expression correlations for ARL17A. Potential eSNPs for ARL17A include rs242557 (Table 2), which is highly associated with PSP but more modestly correlated with ARL17A expression, and rs8079215, which is highly correlated with ARL17A expression but not as strongly with risk for PSP. Statistical modeling of these data produce the following conclusions: haplotypes involving H1 and rs242557 alleles predict a highly significant portion of the variability of ARL17A expression; however, essentially all of that variance can be explained by alleles at rs8079215, which are correlated with H1/H2 and rs242557 alleles; and that alleles at rs8079215 cannot predict risk for PSP independent of H1/H2 status even though they are excellent predictors of ARL17A expression. In sum, risk for PSP does not rise and fall with ARL17A expression. The global MAPT brain region expression analyzed here does not explain how rs242557 alleles confer risk to PSP. Yet this SNP or a correlated polymorphism is assumed to have a regulatory effect because there are no coding variants in MAPT brain isoforms that are candidate pathogenic variants. One possible explanation is that rs242557 alleles could affect alternative splicing without altering total MAPT expression levels22,23.

Because AD and PSP are tauoptahies, and because H1 is a shared risk factor for PSP and PD, we determined whether any confirmed AD24–28 or PD29 loci also produced suggestive evidence for PSP association (Supplementary Table 8). Besides the overlap between PD and PSP at MAPT, the single noteworthy result was from rs2075650 in TOMM40 that yielded PJ = 1.28 × 10−5 for association with PSP. TOMM40 is adjacent to APOE and rs2075650 tags the AD risk allele, e4, in APOE. The effect in PSP is opposite that seen in AD: e4 frequency is elevated in AD and diminished in PSP (for rs2075650, the estimated MAF in cases is 0.11 versus 0.15 in both our young and older controls; r2 between rs2075650 and e4 is 0.33).

Our work suggests a number of intriguing insights into PSP. One comes from EIF2AK3, a gene that encodes PERK, a component of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) unfolded protein response (UPR). When excess unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, PERK is activated and protein synthesis is inhibited allowing the ER to clear mis-folded proteins and return to homeostasis. The UPR is active in PSP30, AD31, and PD32. In PSP, activated PERK is in neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes30. In AD, activated UPR components are found in pre-tangle neurons in a number of brain regions31. In PD, UPR activation occurs in neuromelanin containing dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra32. How the UPR contributes to PSP pathogenesis is unclear because the primary mis-folded protein in PSP, tau, is not a secreted protein and thus is not expected to traffic through the ER.

The PSP susceptibility gene STX6 encodes syntaxin 6 (Stx6), a SNARE class protein. SNARE proteins are part of the cellular machinery that catalyzes the fusion of vesicles with membranes33. Stx6 is localized to the trans-Golgi network and endosomal structures34. Since our work implicates ER-stress in PSP pathogenesis, genetic variation at STX6 could influence movement of mis-folded proteins from the ER to lysosomes via the endosomal system.

MOBP (PJ = 1 × 10−16), like the myelin basic protein gene (MBP), encodes a protein (MOBP) that is produced by oligodendrocytes and is present in the major dense line of CNS myelin. MOBP is highly expressed in the white matter of the medulla, pons, cerebellum, and midbrain35, regions affected in PSP. Our findings suggest that myelin dysfunction or oligodendrocyte mis-function contributes to PSP pathogenesis.

Our work generates a testable translational hypothesis based on the results for EIK2AK3. Our work suggests that perturbation of the UPR can influence PSP risk, and that the UPR is not just a downstream consequence of neurodegeneration. Thus pharmacologic modulation of the UPR is a potential therapeutic strategy for PSP36,37.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families that participated in this study. This work was funded by grants from the CurePSP Foundation, the Peebler PSP Research Foundation, and National Institutes on Health (NIH) grants R37 AG 11762, R01 PAS-03-092, P50 NS72187, P01 AG17216 [National Institute on Aging(NIA)/NIH], MH057881 and MH077930 [National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)]. Work was also supported in part by the NIA Intramural Research Program, the German National Genome Research Network (01GS08136-4) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HO 2402/6-1), Prinses Beatrix Fonds (JCvS, 01–0128), the Reta Lila Weston Trust and the UK Medical Research Council (RdS: G0501560). The Newcastle Brain Tissue Resource provided tissue and is funded in part by a grant from the UK Medical Research Council (G0400074), by the Newcastle NIHR Biomedical Research Centre in Ageing and Age Related Diseases to the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Research Trust as part of the Brains for Dementia Resarch Project. We acknowledge the contribution of many tissue samples from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. We also acknowledge the 'Human Genetic Bank of Patients affected by Parkinson Disease and parkinsonism' (http://www.parkinson.it/dnabank.html) of the Telethon Genetic Biobank Network, supported by TELETHON Italy (project n. GTB07001) and by Fondazione Grigioni per il Morbo di Parkinson. The University of Toronto sample collection was supported by grants from Wellcome Trust, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Brain-Net-Germany is supported by BMBF (01GI0505). RdS, AJL and JAH are funded by the Reta Lila Weston Trust and the PSP (Europe) Association. RdS is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (Grant G0501560) and Cure PSP+. ZKW is partially supported by the NIH/NINDS 1RC2NS070276, NS057567, P50NS072187, Mayo Clinic Florida (MCF)Research Committee CR programs (MCF #90052030 and MCF #90052030), and the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch (MCF #90052031/PAU #90052). The Mayo Clinic College of Medicine would like to acknowledge Matt Baker, Richard Crook, Mariely DeJesus-Hernandez and Nicola Rutherford for their preparation of samples. PP was supported by a grant from the Government of Navarra ("Ayudas para la Realización de Proyectos de Investigación" 2006–2007) and acknowledges the "Iberian Atypical Parkinsonism Study Group Researchers", i.e. Maria A. Pastor, Maria R. Luquin, Mario Riverol, Jose A. Obeso and Maria C Rodriguez-Oroz (Department of Neurology, Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain), Marta Blazquez (Neurology Department, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain), Adolfo Lopez de Munain, Begoña Indakoetxea, Javier Olaskoaga, Javier Ruiz, José Félix Martí Massó (Servicio de Neurología, Hospital Donostia, San Sebastián, Spain), Victoria Alvarez (Genetics Department, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain), Teresa Tuñon (Banco de Tejidos Neurologicos, CIBERNED, Hospital de Navarra, Navarra, Spain), Fermin Moreno (Servicio de Neurología, Hospital Ntra. Sra. de la Antigua, Zumarraga, Gipuzkoa, Spain), Ainhoa Alzualde (Neurogenétics Department, Hospital Donostia, San Sebastián, Spain).

The datasets used for older controls were obtained from Database for Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGap) at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap. Funding support for the “Genetic Consortium for Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease” was provided through the Division of Neuroscience, NIA. The Genetic Consortium for Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (Study accession number: phs000168.v1.p1) includes a genome-wide association study funded as part of the Division of Neuroscience, NIA. Assistance with phenotype harmonization and genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination, was provided by Genetic Consortium for Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Funding support for the “CIDR Visceral Adiposity Study” (Study accession number: phs000169.v1.p1) was provided through the Division of Aging Biology and the Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology, NIA. The CIDR Visceral Adiposity Study includes a genome-wide association study funded as part of the Division of Aging Biology and the Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology, NIA. Assistance with phenotype harmonization and genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination, was provided by Heath ABC Study Investigators. Funding support for the Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP) was provided through a cooperative agreement (U01HG004608) with the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), with additional funding from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) The samples used for PMRP analyses were obtained with funding from Marshfield Clinic, Health Resources Service Administration Office of Rural Health Policy grant number D1A RH00025, and Wisconsin Department of Commerce Technology Development Fund contract number TDF FYO10718. Funding support for genotyping, which was performed at Johns Hopkins University, was provided by the NIH (U01HG004438). Assistance with phenotype harmonization and genotype cleaning was provided by the eMERGE Administrative Coordinating Center (U01HG004603) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The datasets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from dbGaP at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap through dbGaP accession number phs000170.v1.p1.

PSP Genetics Study Group coauthors

Roger L. Albin31,32, Elena Alonso33,34, Angelo Antonini35,36, Manuela Apfelbacher37, Steven E. Arnold38, Jesus Avila39, Thomas G. Beach40, Sherry Beecher41, Daniela Berg42, Thomas D. Bird43, Nenad Bogdanovic44, Agnita J.W. Boon45, Yvette Bordelon46, Alexis Brice47,48,49, Herbert Budka50, Margherita Canesi35, Wang Zheng Chiu45, Roberto Cilia35, Carlo Colosimo51, Peter P. De Deyn52, Justo García de Yebenes53, Laura Donker Kaat45, Ranjan Duara54, Alexandra Durr47,48,49, Sebastiaan Engelborghs52, Giovanni Fabbrini51, NiCole A. Finch55, Robyn Flook56, Matthew P. Frosch57, Carles Gaig58, Douglas R. Galasko59, Thomas Gasser42, Marla Gearing60, Evan T. Geller41, Bernardino Ghetti61, Neill R. Graff-Radford62, Murray Grossman63, Deborah A. Hall64, Lili-Naz Hazrati65, Matthias Höllerhage66, Joseph Jankovic67, Jorge L. Juncos68, Anna Karydas69, Hans A. Kretzschmar70, Isabelle Leber47,48,49, Virginia M. Lee41, Andrew P. Lieberman71, Kelly E. Lyons72, Claudio Mariani35, Eliezer Masliah59,73, Luke A. Massey74, Catriona A. McLean75, Nicoletta Meucci35, Bruce L. Miller69, Brit Mollenhauer76,77, Jens C. Möller66, Huw R. Morris78, Chris Morris79, Sean S. O’Sullivan74, Wolfgang H. Oertel66, Donatella Ottaviani51, Alessandro Padovani80, Rajesh Pahwa72, Gianni Pezzoli35, Stuart Pickering-Brown81, Werner Poewe82, Alberto Rabano83, Alex Rajput84, Stephen G Reich85, Gesine Respondek66, Sigrun Roeber70, Jonathan D. Rohrer86, Owen A. Ross55, Martin N. Rossor86, Giorgio Sacilotto35, William W. Seeley69, Klaus Seppi82, Laura Silveira-Moriyama74, Salvatore Spina61, Karin Srulijes42, Peter St. George-Hyslop65,87, Maria Stamelou66, David G. Standaert88, Silvana Tesei35, Wallace W. Tourtellotte89, Claudia Trenkwalder77, Claire Troakes90, John Q. Trojanowski41, Juan C. Troncoso91, Vivianna M. Van Deerlin41, Jean Paul G. Vonsattel92, Gregor K. Wenning82, Charles L. White93, Pia Winter94, Chris Zarow95, Anna L. Zecchinelli35

PSP Genetics Study Group coauthor affiliations 31Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 32Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VA Ann Arbor Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 33Neurogenetics laboratory, Division of Neurosciences, University of Navarra Center for Applied Medical Research, Pamplona, Spain. 34Neurogenetics laboratory, Division of Neurosciences, University of Navarra Center for Applied Medical Research, Pamplona, Spain. 35Parkinson Institute, Istituti Clinici di Perfezionamento, Milan, Italy. 36Department for Parkinson's Disease, IRCCS San Camillo, Venice, Italy. 37Institute of Legal Medicine, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany. 38Department of Psychiatry, Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 39Centro de Biologia Molecular Severo Ochoa (CSIC-UAM), Campus Cantoblanco, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. 40Civin Laboratory for Neuropathology, Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, Arizona, USA. 41Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 42Center of Neurology, Department of Neurodegeneration, Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, University of Tübingen and German Center for Neurodegenerative diseases (DZNE), Tübingen, Germany. 43Departments of Medicine, Neurology, and Medical Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. 44Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, Hudding University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. 45Department of Neurology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 46Department of Neurology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA. 47Centre de Recherche de l'Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle épinière, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France. 48Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Paris, France. 49Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, France. 50Institute of Neurology, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria. 51Dipartimento di Scienze Neurologiche e Psichiatriche, Sapienza Università di Roma, Rome, Italy. 52Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. 53Department of Neurology, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. 54Wien Center for Alzheimer's Disease and Memory Disorders, Mt Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, Florida, USA. 55Department of Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA. 56Centre for Neuroscience, Flinders University and Australian Brain Bank Network, Victoria, Australia. 57C.S. Kubik Laboratory for Neuropathology and Mass General Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 58Neurology Service, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Hospital Clínic, IDIBAPS, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. 59Department of Neurosciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 60Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 61Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. 62Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA. 63Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 64Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA. 65Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Disease, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 66Department of Neurology, Philipps University, Marburg, Germany. 67Department of Neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA. 68Depratment of Neurology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. 69Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA. 70Institut für Neuropathologie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and Brain Net Germany, Munich, Germany. 71Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. 72Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, USA. 73Department of Pathology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA. 74Reta Lila Weston Institute, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, UK. 75Victorian Brain Bank Network, Mental Health Research Institute, Victoria, Australia. 76Department of Neurology, Georg-August University, Goettingen, Germany. 77Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik, University of Goettingen, Kassel, Germany. 78MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. 79Newcastle Brain Tissue Resource, Newcastle University, Institute for Ageing and Health, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. 80Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Institute of Neurology, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy. 81Neurodegeneration and Mental Health Research Group, Faculty of Human and Medical Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. 82Department of Neurology, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria. 83Department of Neuropathology and Tissue Bank Fundación CIEN, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. 84Division of Neurology, Royal University Hospital, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan, Canada. 85Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA. 86Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, UK. 87Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 88Department of Neurology, Center for Neurodegeneration and Experimental Therapeutics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA. 89Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Healthcare Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA. 90Department of Clinical Neuroscience, MRC Centre for Neurodegeneration Research, King's College London, London, UK. 91Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA. 92Department of Pathology and the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York City, NY, USA. 93Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA. 94Institute of Human Genetics, Justus-Liebig University, Giessen, Germany. 95Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, University of Southern California, Downey, CA, USA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Co-first authors G.U.H., N.M.M., D.W.D., and P.M.A.S. and senior authors U.M. and G.D.S., contributed equally to this project. G.U.H. and U.M. initiated this study and consortium, drafted the first grant and protocol, coordinated the European sample acquisition and preparation, contributed to data interpretation, and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. N.M.M. conducted the analyses and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. D.W.D. contributed to study design, data interpretation, and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. P.M.A.S. contributed in the selection of controls for both phases of the experiment, data QC, data analysis and content curation for the replication phase custom array. L.S.W. participated in the initial association analysis, eSNP and pathway analysis, and functional annotation of SNPs in top genes. L.K. participated in genotype QC and analysis. R.R and R.DeSilva participated in study design, sample preparation and revising the manuscript for content. I.Litvan, D.E.R., J.C.V., P.H., Z.K.W., R.J.U., J.V., H.I.H., R.G.G., W.M., S.G., E.T., B.B., P.P., and the PSP Genetics Study Group (R.L.A., E.A., A.A., M.A., S.E.A., J.A., T.B., S.B., D.B., T.D.B., N.B., A.J.W.B., Y.B., A.B., H.B., M.C., W.Z.C., R.C., C.C., P.P.D., J.G.D., L.D.K., R.Duara, A.Durr, S.E., G.F., N.A.F., R.F., M.P.F., C.G., D.R.G., T.G., M.Gearing, E.T.G., B.G., N.R.G.R., M.Grossman, D.A.H., L.H., M.H., J.J., J.L.J., A.K., H.A.K., I.Leber, V.M.L., A.P.L., K.L., C.Mariani, E.M., L.A.M., C.A.M., N.M., B.L.M., B.M., J.C.M., H.R.M., C.Morris, S.S.O., W.H.O., D.O., A.P., R.P., G.P., S.P.B., W.P., A.Rabano, A.Rajput, S.G.R., G.R., S.R., J.D.R., O.A.R., M.N.R., G.S., W.W.S., K.Seppi, L.S.M., S.S., K.Srulijes, P.S.G., M.S., D.G.S., S.T., W.W.T., C.Trenkwalder, C.Troakes, J.Q.T., J.C.T., V.M.V., J.P.G.V., G.K.W., C.L.W., P.W., C.Z., and A.L.Z.) participated in characterization, preparation and contribution of samples from patients with PSP. L.B.C. coordinated project, sample acquisition and selection, and managed phenotypes. M.R.H. conducted eSNP and pathway analysis. A.Dillman performed mRNA expression experiments in human brain. M.P.V. and D.G.H. performed mRNA expression experiments in human brain, contributed to the design of eQTL experiments. J.R.G. performed computational and statistical analysis of the expression QTL data, contributed to the design of eQTL experiments. M.R.C. and A.B.S. were responsible for overall supervision, design and analysis of eQTL experiments. J.C.V., M.J.F., L.I.G., J.H., A.J.L., participated in study design, and data analysis discussions. C.E.Y. and T.R. participated in the initial design of experiments. B.D. supervised analyses and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. H.H. supervised genotyping and platform and sample selection, participated in analyses, and reviewed the manuscript. G.D.S. led the consortium, supervised study design, coordinated the United States sample acquisition and preparation, contributed to data interpretation, and wrote and coordinated assembly of the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests T.G. serves as an editorial board member of Movement Disorders and Parkinsonism and Related Disorders and is funded by Novartis Pharma, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (NGFN-Plus and ERA-Net NEURON), the Helmholtz Association (HelMA, Helmholtz Alliance for Health in an Ageing Society) and the European Community (MeFoPa, Medndelian Forms of Parkinsonism). T.G. received speakers honoraria from Novartis, Merck-Serono, Schwarz Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim and Valeant Pharma and royalties for his consulting activities from Cefalon Pharma and Merck-Serono. T.G. holds a patent concerning the LRRK2 gene and neurodegenerative disorders. J.H. is consulting for Merck Serono and Eisai. I.Litvan is the founder of the Litvan Neurological Research Foundation, whose mission is to increase awareness, determine the cause/s and search for a cure for neurodegenerative disorders presenting with either parkinsonian or dementia symptoms (501c3).

References

- 1.Hoppitt T, et al. A Systematic Review of the Incidence and Prevalence of Long-Term Neurological Conditions in the UK. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:19–28. doi: 10.1159/000321712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litvan I. Update on progressive supranuclear palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickson DW, Rademakers R, Hutton ML. Progressive supranuclear palsy: Pathology and genetics. Brain Pathology. 2007;17:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamelou M, et al. Rational therapeutic approaches to progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2010;133:1578–1590. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee AC, et al. TDP-43 Proteinopathy and Motor Neuron Disease in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:918–929. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golbe LI, et al. Follow-up study of risk factors in progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 1996;47:148–154. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefansson H, et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker M, et al. Association of an extended haplotype in the tau gene with progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:711–715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruchaga C, et al. 5'-Upstream variants of CRHR1 and MAPT genes associated with age at onset in progressive supranuclear palsy and cortical basal degeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houlden H, et al. Corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy share a common tau haplotype. Neurology. 2001;56:1702–1706. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundar PD, et al. Two sites in the MAPT region confer genetic risk for Guam ALS/PDC and dementia. Hum. Molec. Genet. 2007;16:295–306. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanock SJ, et al. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M. Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:209–213. doi: 10.1038/ng1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zody MC, et al. Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/ng.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian C, et al. Analysis and application of European genetic substructure using 300 K SNP information. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litvan I, et al. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): Report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47:1–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osaki Y, et al. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy. Movement Disorders. 2004;19:181–189. doi: 10.1002/mds.10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy DL, et al. Multiple pigmentation gene polymorphisms account for a substantial proportion of risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:520–528. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrer LA, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rademakers R, et al. High-density SNP haplotyping suggests altered regulation of tau gene expression in progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:3281–3292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caffrey TM, Joachim C, Paracchini S, Esiri MM, WadeMartins R. Haplotype-specific expression of exon 10 at the human MAPT locus. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15:3529–3537. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers AJ, et al. The MAPT H1c risk haplotype is associated with increased expression of tau and especially of 4 repeat containing transcripts. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;25:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harold D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41 doi: 10.1038/ng.440. 1088-U61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert JC, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seshadri S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010;303:1832–1840. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naj AC, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:436–441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollingworth P, et al. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:429–435. doi: 10.1038/ng.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nalls MA, et al. Imputation of sequence variants for identification of genetic risks for Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet. 2011;377:641–649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unterberger U, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress features are prominent in Alzheimer disease but not in prion diseases in vivo. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2006;65:348–357. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000218445.30535.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoozemans JJM, et al. The Unfolded Protein Response Is Activated in Pretangle Neurons in Alzheimer's Disease Hippocampus. Amer J Pathol. 2009;174:1241–1251. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoozemans JJ, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs--engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendler F, Tooze S. Syntaxin 6: the promiscuous behaviour of a SNARE protein. Traffic. 2001;2:606–611. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.20903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montague P, McCallion AS, Davies RW, Griffiths IR. Myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein: a family of abundant CNS myelin proteins in search of a function. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:479–487. doi: 10.1159/000095110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheper W, Hoozemans JJM. Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein Quality Control in Neurodegenerative Disease: The Good, the Bad and the Therapy. Curr Medicinal Chem. 2009;16:615–626. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paschen W, Mengesdorf T. Cellular abnormalities linked to endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction in cerebrovascular disease - therapeutic potential. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2005;108:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J, Devlin B, Ringquist S, Trucco M, Roeder K. Screen and clean: a tool for identifying interactions in genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:275–285. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauw JJ, et al. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy) Neurology. 1994;44:2015–2019. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickson DW, et al. Office of rare diseases neuropathologic criteria for corticobasal degeneration. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2002;61:935–946. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.11.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee AB, Luca D, Klei L, Devlin B, Roeder K. Discovering genetic ancestry using spectral graph theory. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:51–59. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crossett A, et al. Using ancestry matching to combine family-based and unrelated samples for genome-wide association studies. Stat Med. 2010;29:2932–2945. doi: 10.1002/sim.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian C, Plenge RM, Ransom M, Lee A, Villoslada P. Analysis and application of European genetic substructure using 300K SNP information. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luca D, et al. On the use of general control samples for genome-wide association studies: genetic matching highlights causal variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.003. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibbs JR, et al. Abundant quantitative trait Loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.