Abstract

Objective

To refine a previously reported linkage peak for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26, and conduct follow-up analyses and a fine-mapping association study across the region to identify new candidate genes for endometriosis.

Design

Case-control study.

Setting

Academic research.

Subject(s)

Cases = 3,223 women with surgically confirmed endometriosis; Controls = 1,190 women without endometriosis and 7,060 population samples.

Intervention(s)

Analysis of 11,984 SNPs on chromosome 10.

Main outcome measure(s)

Allele frequency differences between cases and controls.

Results

Linkage analyses on families grouped by endometriosis symptoms (primarily subfertility) provided increased evidence for linkage (logarithm of odds (LOD) score = 3.62) near a previously reported linkage peak. Three independent association signals were found at 96.59 Mb (rs11592737, P=4.9 × 10−4), 105.63 Mb (rs1253130, P=2.5 × 10−4) and 124.25 Mb (rs2250804, P=9.7 × 10−4). Analyses including only samples from linkage families supported the association at all three regions. However, only rs11592737 in the cytochrome P450 subfamily C (CYP2C19) gene was replicated in an independent sample of 2,079 cases and 7060 population controls.

Conclusion(s)

The role of the CYP2C19 gene in conferring risk for endometriosis warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Endometriosis, linkage, association, subfertility, CYP2C19

Introduction

Endometriosis, a disease affecting 6–10% of women of reproductive age, is defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue in sites outside of the uterus, most commonly the pelvic peritoneum, ovaries and recto-vaginal septum (1). Although symptoms vary, affected women most commonly experience chronic pelvic pain, severe dysmenorrhea and subfertility. The disease is inherited as a complex genetic trait (1–3), and aggregates within families in humans (4,5) and non-human primates (6). Genetic factors accounted for 52% of the variation in liability to endometriosis in an Australian twin study, with a relative-recurrence risk of 2.34 for sibs of endometriosis patients (7).

We previously reported significant genetic linkage (logarithm of odds (LOD) score >3) to endometriosis on chromosome 10q26 in a study of 1,176 families (8). We have now performed further analyses to refine the linkage peak and extensive fine mapping to identify regions associated with risk of developing endometriosis. We used latent class analysis to determine whether stratification by disease stage and/or symptoms was possible, and the relative contribution of these factors to linkage in the region. Subsequently, we genotyped a high-density SNP panel in 1,144 familial cases and 1,190 controls. The best association signals were detected at three independent loci although only SNPs at the 96.59 Mb region, harbouring the cytochrome P450 family subfamily C (CYP2C19) gene, showed evidence of replication in independent case:control samples.

Material and Methods

Refining the linkage peak

Latent class analysis

The linkage study included 931 affected sister pair families collected by the Queensland Institute of Medical Research (QIMR) and 245 collected by the University of Oxford (8,9). To refine the published linkage peak we sought to increase the genetic homogeneity of the sample by examining endometriosis subtypes using information about self-rated symptoms of pelvic pain (ever experiencing severe pelvic pain) and subfertility (failure to conceive after trying for 12 months) and physician-diagnosed disease stage (based on the revised American Fertility Society (rAFS) classification system) (10). As it can be difficult to stage disease accurately using clinical records alone, a simplified two-stage system was used (9,10): stage A (rAFS I–II or some ovarian disease plus a few adhesions) and stage B (rAFS III–IV). Latent class analysis (LCA), a method to find subtypes of related cases from multivariate categorical data, was used to investigate the presence and composition of endometriosis subgroups using the Bayes Information Criterion (BIC) (11) as the index of model goodness-of-fit. The null hypothesis of a one-class (group) solution (i.e. all individuals belong to the same class or group) is rejected if models with more parameters (groups) provide a smaller BIC value.

Linkage and ordered subset analyses

To investigate whether stratifying on subfertility provided a more phenotypically homogenous sample, the approach of Cox et. al. (12) was adapted to conduct linkage analyses with families weighted according to reported subfertility (0=subfertility, 1=no subfertility). Non-parametric, multipoint, affected-only LOD scores were calculated on the basis of the S-pairs scoring function and an exponential allele-sharing model (exponential LOD (expLOD) scores) using the ALLEGRO analysis package (13). Ordered subset analyses (OSA) (14) were performed to assess the increased evidence of linkage in subsets of families ordered by their subfertility value relative to the entire sample.

Association mapping sample selection

For the fine-mapping association analyses we genotyped unrelated cases mostly from the families included in the linkage study (8). Subject to DNA availability, cases were chosen to include individuals with the most severe disease, i.e. the highest disease stage or the youngest age at onset if both sisters had the same disease stages. There were 871 such cases from the 931 QIMR families and 231 from Oxford. A further 40 QIMR cases were chosen from families not included in the original linkage analysis but containing a proband plus at least 2 affected relatives using the same criteria.

QIMR controls (N=952) were chosen from female twin pairs originally recruited for a study of gynaecological health (15), including one sample from pairs where neither sister had self-reported endometriosis. Oxford controls (N=238) were unrelated women recruited in collaborating hospitals who were: 1) undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain, subfertility or other gynaecological complaints, hysterectomy or sterilisation; 2) free of endometriosis at surgery, and 3) without a previous surgical diagnosis of endometriosis. All study participants were volunteers, had signed written informed consent and had provided a blood sample for DNA extraction. Ethics approval was obtained from the QIMR Human Research Ethics Committee, and the UK Regional Multi-centre and local Research Ethics Committees.

Fine-mapping

SNP selection

The 95% confidence interval for both the published (region 112–129 Mb) and ‘fertility-related’ (region 94–107 Mb) linkage peaks extends over 36 Mb (NCBI build 36; http://www.ensembl.org). Assays for 13,589 SNPs were manufactured and the genotyping and initial quality control performed at Illumina Inc (San Diego, CA, USA) on an Illumina Infinium iSelect custom platform. Across the entire 36 Mb region, gene-based SNPs were included in all exons and 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions for approximately 250 genes, and under the published and fertility-related linkage peaks SNPs tagged to a minimum pair-wise r2 of 0.97. In an attempt to capture information from rare SNPs (minor allele frequencies (MAFs) <1%)) we did not exclude loci with MAFs of 0 in the HapMap (www.hapmap.org) although most variants were common in our dataset: only 6% of SNPs had MAFs <1% (range 0.0002–0.0098; Table 1).

Table 1.

Minor allele frequency ranges for 11,984 polymorphic SNPs included in the fine-mapping association analyses.

| Minor allele frequencies | SNPs per frequency class |

|---|---|

| Common | |

| MAF > 5% | 10,245 (85.5%) |

| Low frequency | |

| MAF 1–5% | 1008 (8.4%) |

| Rare | |

| MAF < 1% | 731 (6.1%) |

Quality control and association analyses

Additional quality control was performed on genotype data from 2,369 (1,158 cases, 1,211 controls) individuals and 12,537 polymorphic SNPs using PLINK (16). We detected and removed individuals with non-Caucasian ancestry and SNPs with >5% missing genotypes or Hardy-Weinberg P-values <1 × 10−4 in control samples. Thereafter, 1,144 cases (911 QIMR; 233 Oxford), 1,190 controls (952 QIMR; 238 Oxford) and 11,984 SNPs remained in the dataset. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) tests of association were performed using PLINK including QIMR and Oxford data as different strata to account for any subtle differences between populations in baseline effect (17). Breslow-Day (BD) tests were conducted to check that the assumptions of the CMH test (i.e. similar effect size across strata) were true. The significance of the association signals was assessed by permutation (10,000 replicates).

Investigation of association in a replication data set

We attempted to replicate the results from the ‘discovery’ sample in an independent set of 2,079 cases (1,383 QIMR; 696 Oxford), all surgically confirmed, without a family history, recruited within the QIMR and Oxford studies. Each was genotyped on Illumina Human670Quad Beadarrays for a genome-wide association (GWA) study (17). There were 7,060 population controls genotyped using: a) Human610Quad (QIMR controls: 1,870 unrelated individuals recruited within the Brisbane Adolescent Twin Study (18,19)) or b) Human1M-Duo beadchips (Oxford controls: 5,190 UK unrelated population controls provided by The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2). Association analysis, and meta-analysis of the P-values for both datasets, were performed using PLINK (16).

Results

Linkage

Latent class analysis

Comparative fits of LCA models determined a two-class solution as the most parsimonious with a minimum BIC of −247.50 (one-class BIC −237.30; three-class BIC −220.81). The main phenotypic measure discriminating between the two classes was subfertility. Class 1 families (CL1: 51.7% of the linkage families; 663 QIMR, 138 Oxford) represented an endometriosis type typically without subfertility (91%), a slightly lower proportion with stage B disease (27%), but more common experience of pelvic pain (80.3%). Class 2 (CL2; 48.3%; 268 QIMR, 107 Oxford) families represented a form typically seen with subfertility (89%), a slightly higher proportion with stage B disease (40%) and less common experience of pelvic pain (72.3%).

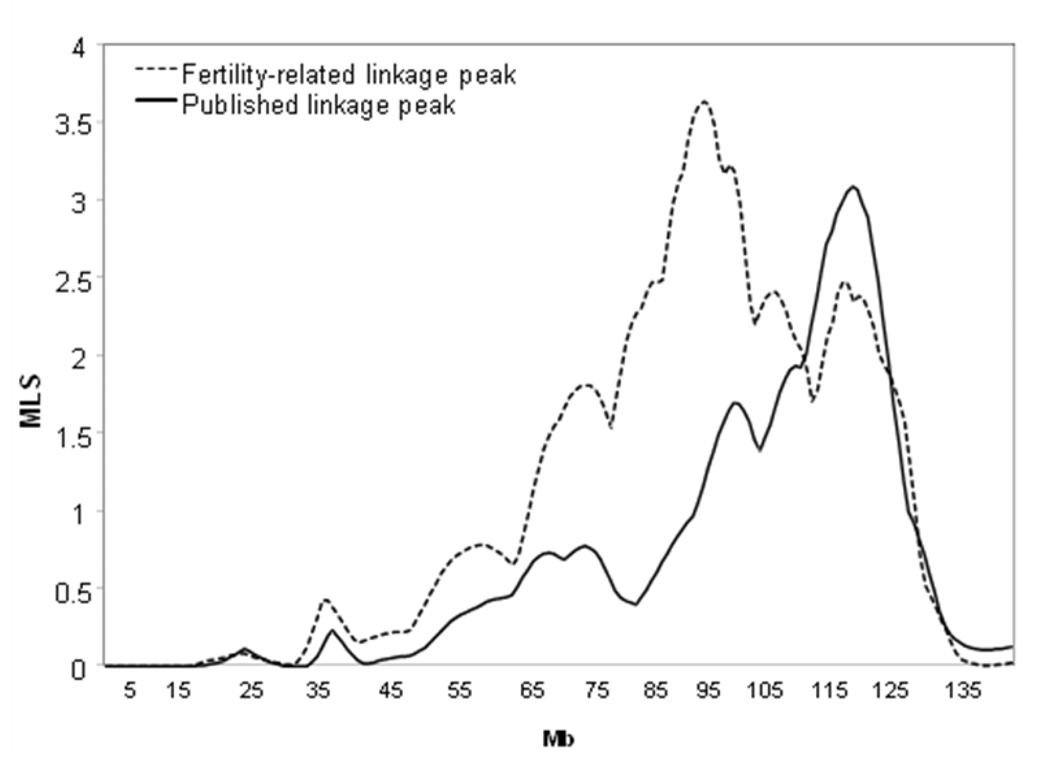

The results of linkage analyses, performed using the subfertility weighting, did not change substantially by including CL2 families only. Restricting the analysis to CL1 families produced an expLOD=3.62 at approximately 98 Mb, 27 Mb closer to the centromere than the published significant linkage peak (expLOD=3.08 at 125 Mb) (Fig. 1). These results were confirmed by the ordered subset analysis, with an increased expLOD=3.58 when families ranked by fertility scores were successively added to the linkage analysis. The increased evidence for linkage in the fertile subset relative to the entire sample (assessed via 10,000 permutations) was significant (P=0.02).

Figure 1.

Chromosome 10 linkage peaks for endometriosis

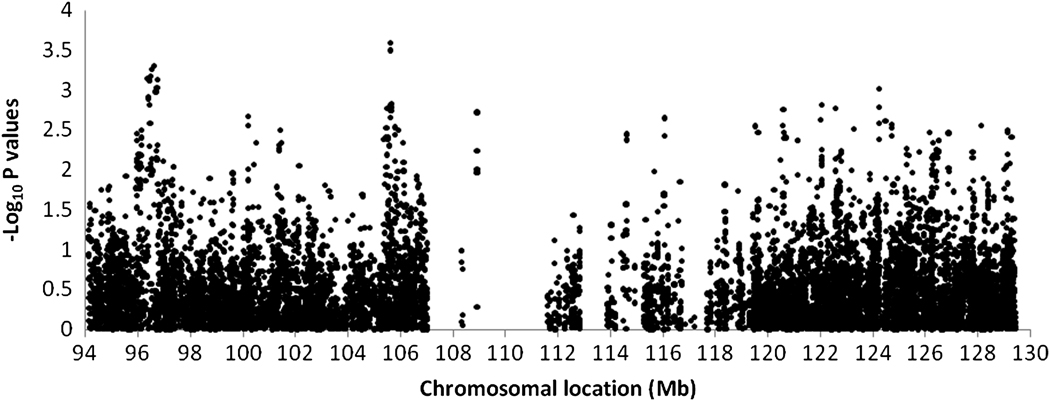

Fine-mapping association analyses in the discovery sample

Nominal signals of association (P<1×10−3), supported by multiple SNPs, were seen in three regions (Table 2, Fig. 2). The SNPs with the smallest P-values were under the fertility-related linkage peak: at ~96.59 Mb (top SNP rs11592737, P=4.9 × 10−4, OR=0.78) in intron 7 of the CYP2C19 gene, and at ~105.63 Mb (rs12573103, P=2.5 × 10−4, OR=1.24) upstream of the SH3 and PX domain-containing adaptor (SH3PXD2A) gene. The next smallest P-value was for rs2250804 at 124.25 Mb (P=9.7 × 10−4; OR=1.22) under the published linkage peak, in intron 3 of the HtrA serine peptidase 1 precursor (HTRA1) gene. All three signals were independent, with no linkage disequilibrium between the SNPs. However, the permutation analysis showed that none of association signals was significant at a study-wide level (P<0.05), with corrected empirical P-values of 0.92, 0.75 and 0.99 for rs11592737, rs12573103 and rs2250904, respectively.

Table 2.

Association signal in the 96.5 Mb and 105.6 Mb regions for the fine-mapping (discovery), replication, and combined datasets. Results are shown for the most significant SNP in each region, and for the replication and meta-analysis for SNPs in moderate LD (r2 > 0.5) for which the replication samples had been genotyped.

| Linkage peak | Fine-mapping | Replication | Meta-analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Position | r2* | RAF** | P | OR*** | P | OR | P | OR |

| 96.59 Mb | |||||||||

| rs11592737 | 96593404 | 0.79 (A) | 4.9 × 10−4 | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| rs12243416 | 96444146 | 0.99 | 0.79 (G) | 7.6 × 10−4 | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | 5.0 × 10−2 | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 8.4 × 10−4 | 1.14 (1.05–1.22) |

| rs11188067 | 96483699 | 0.99 | 0.79 (A) | 6.7 × 10−4 | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | 5.0 × 10−2 | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 8.4 × 10−4 | 1.14 (1.05–1.22) |

| rs7085745 | 96672504 | 0.98 | 0.79 (T) | 1.0 × 10−3 | 1.28 (1.11–1.47) | 4.0 × 10−2 | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 7.6 × 10−4 | 1.14 (1.05–1.22) |

| 105.63 Mb | |||||||||

| rs12573103 | 105629231 | 0.48 (A) | 2.5 × 10−4 | 1.24 (1.10–1.39) | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| rs10748858 | 105629504 | 0.68 | 0.41 (G) | 3.2 × 10−4 | 1.24 (1.10–1.39) | 0.60 | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) | 6.0 × 10−3 | 1.09 (1.02–1.15) |

| rs1980653 | 105644154 | 0.94 | 0.49 (T) | 1.8 × 10−3 | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) | 0.11 | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 1.3 × 10−3 | 1.01 (1.04–1.17) |

| rs11191865 | 105662832 | 0.93 | 0.49 (G) | 1.5 × 10−3 | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 0.13 | 1.06(0.98–1.14) | 1.7 × 10−3 | 1.01 (1.04–1.17) |

| 124.25 Mb | |||||||||

| rs2250804 | 124254868 | 0.33 (C) | 9.7 × 10−4 | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| rs2300433 | 124233447 | 0.50 | 0.31 (G) | 4.8 × 10−2 | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 0.44 | 0.96 (0.89–1.05) | 0.53 | 1.04 (0.96–1.14) |

| rs2253755 | 124231547 | 0.50 | 0.31 (G) | 4.5 × 10−2 | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 0.47 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.50 | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) |

r2 values between the best SNPs in each region (in bold) to those included both in the fine-mapping dataset and on the Illumina 610 K chips, calculated using the fine-mapping data.

Risk allele frequency

Odds ratios were calculated for the risk allele, indicated in parentheses

Figure 2.

Fine-mapping association analysis results across the 36 Mb region under the published and fertility-related linkage peaks for endometriosis.

Exploratory analyses were performed limiting cases to those from the previously published linkage families (1,105 cases) and CL1 families only (755 cases). P-values for the SNPs at 96.59 Mb, 105.63 Mb and 124.25 Mb remained the smallest in these analyses. For rs11592737 at 96.59 Mb, a P=9.0 × 10−4 (OR=1.26) was obtained including only linkage family cases but was below background levels including only CL1 family cases (P=5.0 × 10−2; OR=1.18). For rs12573103 at 105.63 Mb, a P=1.0 × 10−4 (OR=1.25) was obtained including only linkage family cases and P=5.3 × 10−5 (OR=1.31) for CL1 cases. The signal for rs2250804 at 124.25 Mb was reduced by including only linkage family (P=1.1 × 10−3, OR=1.23) and CL1 (P=1.2 × 10−2, OR=1.19) cases.

Replication analyses in an independent case-control sample

The SNPs with the smallest P-values in the 96.59 Mb, 105.63 Mb and 124.25 Mb regions were not present on the commercial Illumina arrays typed in the replication samples. However, additional SNPs that were in moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD: pairwise r2>0.5) were included in our Illumina iSelect panel, allowing a direct comparison of P-values for the discovery and replication datasets. All three SNPs in LD (r2≥0.98) with rs11592737 at 96.59 Mb showed nominal evidence of association (P=4.0 × 10−2 for rs7085745 and 5.0 × 10−2 for rs12243416 and rs11188067; ORs=1.10) in the replication dataset (Table 2), with corresponding P-values between 3.1–4.5 × 10−4 (ORs=1.14) in the meta-analysis of the fine-mapping discovery and replication datasets (Table 2).

There was no replication signal for SNPs at either 105.63 Mb or 124.25 Mb. The SNP in highest LD with rs12573103 at 105.63 Mb (rs1980653, r2=0.94) had a P=0.60 (OR=1.02) in the replication dataset. The two SNPs in highest LD with rs2250804 at 124.25 Mb (rs2300433 and rs2253755, r2=0.50) had P-values of 0.44 and 0.47 in the replication dataset (Table 2).

Discussion

Analysis of endometriosis stage and pelvic pain and subfertility symptoms identified two classes of families, distinguished primarily by the presence or absence of subfertility. Separate linkage analyses with the two classes produced significantly increased evidence for linkage amongst families without subfertility, shifting the linkage peak approximately 27 Mb. We genotyped SNPs at high density across the region covered by both the published and fertility-related linkage peaks and found evidence of association at three independent loci. Although this was not significant at a study-wide level, there was evidence for replication of the signal(s) at 96.59 Mb within the CYP2C19 gene in the independent set of endometriosis cases.

The most significantly associated SNP at 96.59 Mb is in intron 7 of CYP2C19, which participates in the metabolism of drugs and oestrogen including conversion of oestradiol (E2) to oestrone (E1), and the production of E1 and E2 2α- and 16α-hydroxylation metabolites (20,21). The key SNP rs11592737 is in complete LD with rs12248560 (the second best SNP in the region), a functional variant located in the CYP2C19 promoter. The rs12248560 “T” allele (CYP2C19*17; http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2c19.htm) increases the rate of CYP2C19 transcription and was initially thought to produce an ‘ultra-rapid’ metaboliser form of the CYP2C19 protein (22), although a recent review found drug metabolic rates within the ranges seen for wild-type homozygotes (23).

Further evidence for a role for CYP2C19 in diseases influenced by oestrogen comes from a recent study showing a decreased risk of breast cancer in rs12248560 carriers, possibly through increased catabolism resulting in lower overall oestrogen levels (24). CYP2C19 has also been associated with endometriosis in a small study of 50 cases and 50 controls suggesting that affected women were significantly more likely (P=0.023; OR=3.12) to be heterozygous carriers of rs4244285, a splice site defect that abrogates gene expression (25). However, these findings were not replicated in another small study of 46 cases and 39 controls (26). While both studies were clearly under-powered, the initial study adds further support to CYP2C19 as a plausible endometriosis candidate gene. The P-value for rs4244285 in our discovery sample was only nominally significant (P=0.011; OR=1.23), indicating this SNP is not driving our association signal in the region. Several lines of evidence now point to a role for CYP2C19 either through the effect on transcription of the rs12248560 variant or additional rare and low frequency alleles in LD with this SNP. The association result does not account for the linkage signal. Linkage to this region could result from a combination of a common variant like the one described here in CYP2C19 and rare variants of larger effect that might be observed in only a few families.

There was no evidence for replication of the 105.63 Mb or 124.25 Mb signals. The directions of the effects were the same for both the fine-mapping and replication datasets, and both regions harbour plausible candidate genes for endometriosis: SH3PXD2A is an interaction partner of ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (ADAM12), which has a role in uterine decidualization in mice (27, 28). HTRA1 is upregulated in human decidual cells, suggesting a role in preparing the endometrium for embryo implantation (29). It is likely that these associations represent false positive signals, although we were unable to test the key SNPs directly in the replication study. Additionally, the discovery sample used familial cases but these were not available for the replication sample, and non-familial cases may have different underlying disease aetiology.

We detected evidence of genetic association in a region of significant linkage to endometriosis on chromosome 10. This signal does not fully account for the previously reported or fertility-related linkage peaks. However, the finding of suggestive association, and the presence of an extremely plausible candidate gene in the region of association, suggest that further investigation is warranted. Future studies should include replication in other samples, a search for rare and novel genetic variants and gene expression studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women who participated in the QIMR, OXEGENE studies, and Endometriosis Associations for supporting study recruitment. The QIMR Study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (241944, 339462, 389927,389875, 389891, 389892, 389938, 443036, 442915, 442981, 496610, 496739, 552485, 552498), the Cooperative Research Centre for Discovery of Genes for Common Human Diseases (CRC), Cerylid Biosciences (Melbourne), and donations from Neville and Shirley Hawkins, the Endometriosis Associations of Queensland and Western Australia, and the family of the late Kim Goodwin. The fine-mapping genotyping was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA) grant number R01HD50537. DRN is supported by the NHMRC Fellowship (339462 and 613674) and ARC Future Fellowship (FT0991022) schemes. GWM is supported by the NHMRC Fellowships Scheme (339446, 619667). We thank B. Haddon, D. Smyth, H. Beeby, O. Zheng, B. Chapman and additional research assistants and interviewers for project and database management, sample processing, and genotyping. We thank Brisbane gynaecologist Dr Daniel T O’Connor for confirmation of diagnosis and staging of disease for some Australian patients. We also thank the many hospital directors and staff, gynaecologists, general practitioners, and pathology services in Australia who provided assistance with confirmation of diagnoses. We thank Sullivan Nicolaides and Queensland Medical Laboratory for pro bono collection and delivery of blood samples and other pathology services for assistance with blood collection.

The genome-wide association study was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (WT084766/Z/08/Z), and makes use of WTCCC2 control data generated by the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium. A full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of these data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk. Funding for the WTCCC project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 076113 and 085475. APM is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (WT081682/Z/06/Z). SK is supported by the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre with funding from the Department of Health NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. KTZ is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellowship (WT085235/Z/08/Z). We thank Louise Cotton, Lesley Pope, Gillian Chalk, Gail Farmer (University of Oxford). We also thank Philippe Koninckx, (Leuven, Belgium), Martin Sillem (Heidelberg, Germany), Colm O’Herlihy and Mary Wingfield (Dublin, Ireland), Mette Moen (Trondheim, Norway), Leila Adamyan (Moscow, Russia), Enda McVeigh (Oxford, UK), Christopher Sutton (Guildford, UK), David Adamson (Palo Alto, USA), and Ronald Batt (Buffalo, USA), for providing diagnostic confirmation.

Financial support

Queensland Institute of Medical Research:

National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA): R01HD50537.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia: 241944, 339446, 339462, 389927,389875, 389891, 389892, 389938, 443036, 442915, 442981, 496610, 496739, 552485, 552498, 613674, 619667.

Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship scheme: (FT0991022.

Oxford University:

Wellcome Trust: 084766, 081682, 085235, 076113 and 085475.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest declared.

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson JL, Bischoff FZ. Heritability and molecular genetic studies of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955:239–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02785.x. discussion 93-5, 396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery GW, Nyholt DR, Zhao ZZ, Treloar SA, Painter JN, Missmer SA, et al. The search for genes contributing to endometriosis risk. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:447–457. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy S, Mardon H, Barlow D. Familial endometriosis. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 1995;12:32–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02214126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefansson H, Geirsson RT, Steinthorsdottir V, Jonsson H, Manolescu A, Kong A, et al. Genetic factors contribute to the risk of developing endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 2002;17:555–559. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zondervan KT, Weeks DE, Colman R, Cardon LR, Hadfield R, Schleffler J, et al. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in a large pedigree of rhesus macaques. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:448–455. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treloar SA, O'Connor DT, O'Connor VM, Martin NG. Genetic influences on endometriosis in an Australian twin sample. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:701–710. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treloar SA, Wicks J, Nyholt DR, Montgomery GW, Bahlo M, Smith V, et al. Genomewide linkage study in 1,176 affected sister pair families identifies a significant susceptibility locus for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:365–376. doi: 10.1086/432960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treloar S, Hadfield R, Montgomery G, Lambert A, Wicks J, Barlow DH, et al. The International Endogene Study: a collection of families for genetic research in endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:679–685. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis: 1985. Fertility and Sterility. 1985;43:351–352. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox NJ, Frigge M, Nicolae DL, Concannon P, Hanis CL, Bell GI, et al. Loci on chromosomes 2 (NIDDM1) and 15 interact to increase susceptibility to diabetes in Mexican Americans. Nature Genetics. 1999;21:213–215. doi: 10.1038/6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudbjartsson DF, Jonasson K, Frigge ML, Kong A. Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analys. Nat Genet. 2000;25:12–13. doi: 10.1038/75514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser ER, Watanabe RM, Duren WL, Bass MP, Langefeld CD, Boehnke M. Ordered Subset Analysis in Genetic Linkage Mapping of Complex Trait. Genetic Epidemiology. 2004;27:53–63. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treloar SA, Do KA, O'Connor VM, O'Connor DT, Yeo MA, Martin NG. Predictors of hysterectomy: an Australian study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:945–954. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Painter JN, Anderson CA, Nyholt DN, MacGregor S, Lin J, Lee SH, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis. Nat Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ng.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGregor B, Pfitzner J, Zhu G, Grace M, Eldridge A, Pearson J, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to size, color, shape, and other characteristics of melanocytic naevi in a sample of adolescent twins. Genet Epidemiol. 1999;16:40–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1999)16:1<40::AID-GEPI4>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu G, Duffy DL, Eldridge A, Grace M, Mayne C, O'Gorman L, et al. A major quantitative-trait locus for mole density is linked to the familial melanoma gene CDKN2A: a maximum-likelihood combined linkage and association analysis in twins and their sibs. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:483–492. doi: 10.1086/302494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AJ, Cai MX, Thomas PE, Conney AH, Zhu BT. Characterization of the oxidative metabolites of 17beta-estradiol and estrone formed by 15 selectively expressed human cytochrome p450 isoforms. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3382–3398. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cribb AE, Knight MJ, Dryer D, Guernsey J, Hender K, Tesch M, et al. Role of polymorphic human cytochrome P450 enzymes in estrone oxidation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:551–558. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sim SC, Risinger C, Dahl ML, Aklillu E, Christensen M, Bertilsson L, et al. A common novel CYP2C19 gene variant causes ultrarapid drug metabolism relevant for the drug response to proton pump inhibitors and antidepressants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li-Wan-Po A, Girard T, Farndon P, Cooley C, Lithgow J. Pharmacogenetics of CYP2C19: functional and clinical implications of a new variant CYP2C19*17. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justenhoven C, Hamann U, Pierl CB, Baisch C, Harth V, Rabstein S, et al. CYP2C19*17 is associated with decreased breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cayan F, Ayaz L, Aban M, Dilek S, Gumus LT. Role of CYP2C19 polymorphisms in patients with endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:530–535. doi: 10.1080/09513590902972059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bozdag G, Alp A, Saribas Z, Tuncer S, Aksu T, Gurgan T. CYP17 and CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms in patients with endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Guo W, Chen Q, Fan X, Zhang Y, Duan E. Adam12 plays a role during uterine decidualization in mice. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;338:413–421. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, Kim H, Lee SJ, Choi YM, Lee JY. Abundance of ADAM-8, -9, -10, -12, -15 and -17 and ADAMTS-1 in mouse uterus during the oestrous cycle. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2005;17:543–555. doi: 10.1071/rd04110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie G, Hale K, Li Y, Manuelpillai U, Wallace EM, Salamonsen LA. Distinct expression and localization of serine protease HtrA1 in human endometrium and first-trimester placenta. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3448–3455. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]