Abstract

The urban emergency department is an important site for the detection of HIV infection. Current research has focused on strategies to increase HIV testing in the emergency department. As more emergency department HIV cases are identified, there need to be well-defined systems for linkage to care. We conducted a retrospective study of rapid HIV testing in an urban public emergency department and level I trauma center from June 1, 2008, to March 31, 2010. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the increase in the number of tests and new HIV diagnoses resulting from the addition of targeted testing to clinician-initiated diagnostic testing, describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection, and assess the effectiveness of an HIV clinic based linkage to care team. Of 96,711 emergency department visits, there were 5340 (5.5%) rapid HIV tests performed, representing 4827 (91.3%) unique testers, of whom 62.4% were male and 60.8% were from racial/ethnic minority groups. After the change in testing strategy, the median number of tests per month increased from 114 to 273 (p=0.004), and the median number of new diagnoses per month increased from 1.5 to 4 (p=0.01). From all tests conducted, there were 65 new diagnoses of HIV infection (1.2%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.9%, 1.5%). The linkage team connected over 90% of newly diagnosed and out-of-care HIV-infected patients to care. In summary, the addition of targeted testing to diagnostic testing increased new HIV case identification, and an HIV clinic-based team was effective at linkage to care.

Introduction

The urban emergency department is a key site for the detection of undiagnosed HIV infection. Marginalized and vulnerable populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, the socioeconomically disadvantaged) at higher risk for HIV frequently use the emergency department as their primary or only source of care.1 In addition, studies have found that some patients diagnosed with HIV have visited the emergency department on prior occasions.2,3 Finally, the yield of HIV testing in the emergency department may be greater relative to other medical testing sites.4 For these reasons, emergency departments have played a prominent role in the implementation of the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommending routine HIV screening for all persons aged 13–64 years in areas where the HIV prevalence is above 0.1%.5

As more emergency departments undertake rapid HIV testing efforts, they have used different strategies with regard to patient selection. The 2007 National Emergency Department HIV Testing consortium noted that the word “routine” as used in the CDC guidelines could refer either to choosing patients for testing without regard to risk factors or to less exceptional testing practices, such as opt-out consent.6 Thus, the consortium made explicit the following patient selection strategies: diagnostic testing, which is based on clinical signs or symptoms, targeted screening, which focuses on a defined subpopulation thought to have a higher risk of infection than the general population, and nontargeted screening, in which any patient within the available population may be tested. In addition, emergency department HIV testing programs have used different staffing strategies,7 ranging from the exclusive use of ancillary staff to offer and perform testing to incorporating testing fully into the duties of existing staff.4,8–10

The optimal emergency department testing strategy in terms of staffing and patient selection remains unknown, but studies suggest that the colocation of HIV care in the same hospital as the emergency department may facilitate linkage to care.11 To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effectiveness of a linkage to care team based in a hospital HIV clinic, as opposed to the emergency department social workers, HIV counselor/testers, or public health staff used by many emergency department HIV testing programs.12,13 In addition, programs that have chosen to rely on clinician-initiated testing may seek strategies for increasing the number of tests performed. Thus, the objectives of this study were to: (1) describe and evaluate the addition of targeted testing to a model of clinician-initiated diagnostic testing in order to increase the number of HIV tests performed; (2) characterize new diagnoses of HIV infection with regard to demographics and CD4 cell count, and (3) assess linkage to care outcomes for newly diagnosed as well as out-of-care HIV-infected patients.

Methods

Study design

Using retrospective chart and database review, we evaluated test outcomes, population characteristics, and linkage to care outcomes for an emergency department rapid HIV testing program that was funded in part by a CDC demonstration project designed to increase testing among groups disproportionately affected by HIV. The dates of analysis were June 1, 2008, through March 31, 2010.

Setting and program development

San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) is a 300-bed public safety net hospital for the city and county of San Francisco that provides care to an urban, underserved population. The emergency department is a level I trauma center with approximately 55,000 annual patient visits.

In May 2006, SFGH eliminated the requirement for written consent for HIV testing and added HIV antibody testing to the routine laboratory order form.14 In response to the CDC guidelines issued in September 2006 on routinizing HIV testing in medical settings,5 the SFGH HIV clinic convened meetings with key stakeholders, including hospital administration, the hospital laboratory, the emergency department, and the San Francisco Department of Public Health on how to expand hospital capacity for HIV testing. In February 2007 the hospital switched its entire HIV testing platform to central laboratory-based rapid testing on venipuncture specimens. This service was made available 24 h per day, 7 days per week, with results reported in the electronic medical record (EMR) within 1–2 h after specimen receipt in the laboratory. Prior to the new testing platform rollout, the HIV clinic committed to expanding an existing linkage to care team to the emergency department and other hospital testing sites in order to assist with disclosure of positive results, handle all follow-up appointments, and conduct medical and social work intakes. This team consisted of a registered nurse, a social work associate, and a nurse practitioner.

Testing protocol

From February 2007 through November 2008, clinicians could initiate HIV testing for patients they suspected of having signs or symptoms of HIV infection, i.e., diagnostic testing. In June 2008, the CDC awarded the emergency department HIV testing program a grant to increase the number of patients tested. This funding was used to hire a testing program coordinator, who facilitated a series of in-services among emergency department physicians and staff to raise awareness of the availability of HIV testing, and to support the linkage to care team. Working together, the emergency department and the HIV clinic launched an expanded testing effort with revised criteria for testing on December 1, 2008 (World AIDS Day). Clinical presentations consistent with HIV infection were listed and systematically disseminated to emergency department clinicians on a laminated pocket card. In addition, clinicians were encouraged to undertake targeted testing of two groups of patients: (a) patients with HIV risk factors and (b) patients slated for inpatient admission, regardless of their presenting complaints. If concern existed for acute HIV infection and a rapid test was negative, quantitative HIV viral load testing was available. All patients age 13 and over were potentially eligible for HIV testing in the emergency department.

Nurses drew blood and the hospital laboratory performed rapid HIV antibody testing (Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV Test, Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) on plasma or heparin specimens. Negative rapid test results were considered negative and patients were given written materials on HIV testing and prevention. Positive rapid test results were reported as “preliminary positive” in the EMR and the specimen was retested with enzyme immunoassay (EIA; Genetic Systems HIV-1/HIV-2 Plus O EIA, Bio-Rad, Redmond, WA) and confirmatory immunofluorescence (IFA; Fluorognost HIV-1 IFA, Sanochemia Pharmazeutika, Vienna, Austria) with results available in 1–3 days. If EIA and IFA were both negative, the rapid “preliminary positive” test result was deemed a false-positive, and a final HIV antibody result was reported as negative. If EIA and IFA were both positive, a final HIV antibody result was reported as positive. In cases where the EIA and IFA results were discrepant, specimens were sent to the San Francisco Department of Public Health laboratory for repeat EIA/IFA and Western blot testing. Clinicians disclosed both negative and “preliminary positive” rapid test results prior to emergency department discharge. Patients with preliminary positive rapid test results received packets with resources for follow-up, including drop-in appointment times in the HIV clinic for confirmatory test results within 1–3 days. The hospital laboratory also notified the linkage to care team of all preliminary positive rapid antibody test results to ensure complete follow-up of all patients. The linkage team met patients in person if notified during business hours and otherwise contacted patients within 1 business day. The testing program coordinator provided regular feedback to emergency department clinicians on outcomes for patients diagnosed in the emergency department, including clinic attendance and antiretroviral therapy initiation.

Data collection and analysis

Data were obtained from the hospital laboratory on all emergency department rapid HIV antibody tests from June 1, 2008 to March 31, 2010. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate proportions with confidence intervals. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the median number of tests and new HIV diagnoses per month before and after the expanded program launch. Demographic data on patients undergoing testing was obtained from the EMR. The χ2 test was used to assess associations between demographic characteristics and a positive rapid test result. The emergency department HIV testing program database was queried for additional information on subjects with positive rapid tests results, including rapid test disclosure, prior HIV diagnosis, confirmatory test results, sexual orientation, housing status, CD4 cell count, and time to linkage to care for new diagnoses. Linkage to care was defined as one HIV-related outpatient visit. All analyses were conducted in Stata SE/10. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California San Francisco approved this study.

Results

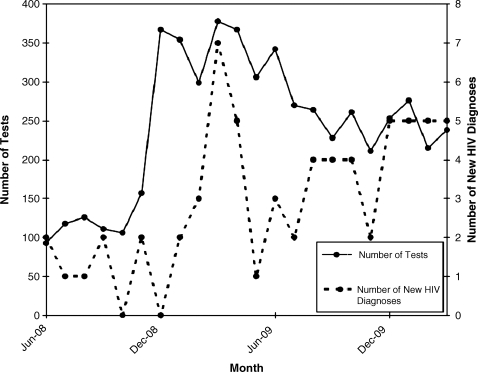

There were 96,711 emergency department visits during the observation period, during which 5340 (5.5%) rapid HIV antibody tests were performed, representing 4827 (91.3%) unique patients. There were 16,662 inpatient admissions (17.2% of emergency department visits), with a median of 738 admissions per month. Of the HIV antibody tests performed, 2430 (45.5%) were on patients who were admitted to the hospital. After the expanded testing launch on December 1, 2008, the number of tests increased from a median of 114 tests per month to 273 tests per month, p=0.004 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Number of rapid HIV tests and new HIV diagnoses by month, June 2008 to March 2010.

The first rapid test result for each patient is shown in Table 1. Rapid test results were positive for 126 testers (2.6%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2%, 3.1%), of which 10 were false-positive, resulting in 116 confirmed cases of HIV infection. The median age of testers was 44 years, (interquartile range [IQR] 31–55 years). Women accounted for nearly 40% of testers but individuals with positive rapid test results were more likely to be male (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Rapid HIV Testing and Testing Newly HIV Positive in the San Francisco General Hospital Emergency Department, June 2008–March 2010

| Total tested, n (%) | Positive rapid test, n (% of total with a positive rapid test) | χ2Test, p | Confirmed rapid test, n (% of total with a confirmed rapid test) | Confirmed HIV infection, newly diagnosed, n (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4827 (100%) | 126 (2.6%) | 116 (2.4%) | 65 (100%) | |

| Age categories (years)a | |||||

| 13–24 | 653 (13.5%) | 9 (1.4%) | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (9.2%) | |

| 25–44 | 1791 (37.1%) | 66 (3.7%) | p=0.001 | 61 (3.4%) | 33 (50.8%) |

| 45–64 | 1961 (40.7%) | 46 (2.4%) | 43 (2.2%) | 23 (35.4%) | |

| >65 | 418 (8.7%) | 5 (1.2%) | 5 (1.2%) | 3 (4.6%) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3014 (62.4%) | 103 (3.4%) | p<0.001 | 96 (3.2%) | 50 (76.9%) |

| Femaleb | 1813 (37.6%) | 23 (1.3%) | 20 (1.1%) | 15 (23.1%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 1692 (35.0%) | 24 (37.0%) | |||

| Black | 1348 (27.9%) | 16 (24.6%) | |||

| Latino | 988 (20.5%) | 14 (21.5%) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 597 (12.4%) | 10 (15.4%) | |||

| Other/unknown | 202 (4.2%) | 1 (1.5%) | |||

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Gay/bisexual | 29 (44.6%) | ||||

| Heterosexual | 23 (35.4%) | ||||

| Unknown | 13 (20.0%) | ||||

| Housing status | |||||

| Permanent (own/rent) | 32 (49.2%) | ||||

| Temporary (e.g., SRO) | 7 (10.8%) | ||||

| Homeless/shelter | 23 (35.4%) | ||||

| Unknown | 3 (4.6%) | ||||

| Median CD4 cell countc,d | 268 | ||||

| IQR | (65, 472) | ||||

| CD4 cell count <200 | |||||

| Yes | 23 (40.0%) | ||||

| No | 36 (60.0%) | ||||

| Admitted to hospital | |||||

| Yes | 29 (44.6%) | ||||

| No | 26 (55.4%) | ||||

New diagnoses include three patients with acute HIV infection (rapid test negative, quantitative viral load >500,000 copies/mL) and one patient who tested positive on a subsequent emergency department visit.

Includes 5 male-to-female transgender patients.

CD4 cell counts available for 59/65 patients.

CD4 cell counts in cells per microliter.

SRO, single room occupancy; IQR, interquartile range.

Of the 116 confirmed cases of HIV infection, 55 individuals had known HIV infection, 58 patients had newly diagnosed HIV infection, and 3 patients were suspected new HIV diagnoses, as they had no record of a previous positive test (2 patients left the emergency department prior to disclosure and 1 was intubated in the emergency department and died during hospitalization). In addition to the 61 patients without a prior known HIV diagnosis, 3 patients presented with symptoms consistent with acute retroviral syndrome and were diagnosed with acute HIV infection based on negative rapid HIV antibody test results and HIV RNA levels higher than 500,000 copies per milliliter. Furthermore, 1 patient with a negative HIV test tested HIV positive on a repeat emergency department visit, for a total of 65 new emergency department HIV diagnoses out of the 5340 tests (1.22%: 95% CI, 0.94%–1.55%). The median number of new HIV diagnoses increased from 1.5 per month to 4 per month during the study period p=0.01 (Fig. 1). Patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection were 76.9% male and 37% white (Table 1). The median CD4 cell count was 268 cells per microliter, with 40% of patients having CD4 cell counts under 200 cells per microliter.

Of the 65 patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection, 58 patients received results at the time of testing and 49 patients were eligible for linkage to outpatient care. Reasons for ineligibility were discharge to a skilled nursing facility after inpatient admission (n=3), incarceration at time of testing (n=2), private insurance incompatible with the publicly funded SFGH HIV clinic (n=2), death during inpatient admission (n=1), and out-of-county residence (n=1). Forty-six patients (93.9%, 95% CI: 83.1, 98.7%) were successfully linked to care, with 73% linked by 7 days, 84% linked by 30 days, and 90% by 90 days. Of the 7 patients whose results were not disclosed at the time of the test, 4 were able to be contacted with results after discharge and 1 presented to the emergency department at a later date; 4 of these patients were also linked to care. Of the 55 patients with known HIV infection, the majority identified as in care (n=39), while a few had out-of-county residence (n=2) or were incarcerated (n=1). Two patients had unknown care status. Of the remaining 11 patients, 10 (90.9%, 95% CI: 58.7%, 99.8%) were successfully relinked to care.

Discussion

A clinician-initiated diagnostic testing model utilizing the hospital laboratory and dedicated linkage to care staff has been described as a successful way to implement and sustain HIV testing in the emergency department.13 We present data to support this claim. In addition, we are the first to describe a successful linkage mechanism based in the hospital HIV clinic, rather than the emergency department. We also demonstrate that additional new diagnoses of HIV infection can be identified through the implementation of strategies other than hiring ancillary staff to conduct testing, namely by re-emphasizing clinical indicators of HIV infection and expanding testing to admitted and high-risk patients. These efforts helped create a “culture change” among busy emergency department clinicians with regard to incorporating HIV testing into their everyday practice. In addition, external funding was used to support the linkage to care team, as concern about patient follow-up has been a commonly cited barrier to clinician-initiated emergency department HIV testing.15 The effort of the program coordinator and the linkage team corresponded to 2 full-time equivalent positions (FTEs). The program's cost effectiveness is reported separately.16

In our study, the linkage to care team achieved rates of success exceeding 90% for both newly diagnosed and out-of-care HIV patients, although studies have shown that connection to care does not necessarily mean patients stay in care.17 Although a small number of patients left the emergency department before disclosure of positive rapid test results, most of these patients were contacted by the linkage team. Even though the turnaround time of the rapid test was one to two hours after specimen receipt in the laboratory, the main barrier to disclosure was discharging patients before test results were available, either because patients wanted to leave or because of overcrowding in the emergency department. The high proportion of patients with previously diagnosed HIV infection in our study is notable, and consistent with other studies.9 Reasons for this finding merit further investigation. Most of these patients did not have prior HIV test results available in the electronic medical record, though a minority did. It may be that patients do not initially disclose their HIV status; they do not believe their diagnosis; they lack documentation of HIV status; or they seek reengagement in care.

The optimal approach to emergency department-based HIV testing remains uncertain.18 A recent study found that nontargeted testing identified only a modestly increased number of new HIV diagnoses compared to physician-initiated diagnostic testing, despite large increases in the number of patients tested.19 A previous blinded study in the SFGH emergency department found that the prevalence of HIV infection was 8.0%, of whom 0.9% had unknown HIV infection.20 While our data indicate that emergency department clinicians can identify populations with a prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection greater than 1%, the additional yield of non-targeted screening in this setting is unknown. Limitations of our data are that we do not know testing rates by category of clinician (e.g., attending, resident) nor we do know the rates and yield of diagnostic versus targeted testing, which in many cases may overlap. However, using the magnitude of the increase in testing allows us to define a reasonable “upper bound” of the proportion of patients tested via targeted criteria: (273–114)/273=58%.

One important goal of testing in medical settings is to identify “hidden” populations with HIV infection—those who would not otherwise be diagnosed in a timely fashion. The demographic characteristics of patients with newly identified HIV infection in the SFGH emergency department differ noticeably from newly identified HIV cases in San Francisco at large. In 2008, those newly diagnosed with HIV in San Francisco were nearly 90% male, at least 80% were men who have sex with men, and half were white.21 In contrast, in our study, new HIV diagnoses were nearly one quarter female or male-to-female transgender, nearly two thirds were racial/ethnic minorities, and approximately one third were heterosexual-identified. In addition, the median CD4 cell count was relatively low at the time of diagnosis. Given these findings, it is our opinion that public hospital emergency department-based testing may identify HIV infection that might go undiagnosed by other HIV testing systems.

Rates of clinician-initiated emergency department rapid HIV antibody testing and identification of new HIV cases can be increased by adding a targeted testing component to diagnostic testing. The integration of laboratory rapid testing with a linkage to care team was an effective strategy for connecting newly diagnosed and out-of-care HIV-infected patients to care in our study. These programmatic features should be explored in other settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Clarissa Ospina-Norvell and Alida Marrero-Calderon for their dedication in linking HIV-infected patients to care, Maria Bahn-Tigaoan for program coordination, Noah Carraher for program monitoring data, and Margaret Wong for the laboratory data used in this analysis. The San Francisco General Hospital HIV testing program was supported by CDC grant PS07-768 “Expanded and Integrated Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Testing for Populations Disproportionately Affected by HIV, Primarily African-Americans.” This publication was made possible by grant number UL1 RR024131 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR. Information on NCRR is available at www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 AI60530 and K23 MH092220-01 (KAC).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Garcia TC. Bernstein AB. Bush MA. Emergency department visitors and visits: Who used the emergency room in 2007? NCHS data brief, no 38. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2010. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db38.pdf. [Mar 7;2011 ]. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db38.pdf [PubMed]

- 2.Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection—South Carolina, 1997–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White DA. Warren OU. Scribner AN. Frazee BW. Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in an emergency department despite an HIV screening program. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:245–250. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christopoulos KA. Schackman BR. Lee G. Green RA. Morrison EA. Results from a New York City emergency department rapid HIV testing program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:420–422. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b7220f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branson BM. Handsfield HH. Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons MS. Lindsell CJ. Haukoos JS, et al. Nomenclature and definitions for emergency department human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing: Report from the 2007 conference of the National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothman RE. Lyons MS. Haukoos JS. Uncovering HIV infection in the emergency department: A broader perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:653–657. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J. Shesser R. Simon G. Establishing an ED HIV screening program: lessons from the front lines. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:658–661. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White DA. Scribner AN. Schulden JD. Branson BM. Heffelfinger JD. Results of a rapid HIV screening and diagnostic testing program in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walensky RP. Arbelaez C. Reichmann WM, et al. Revising expectations from rapid HIV tests in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:153–160. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks G. Gardner LI. Craw J. Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:2665–2678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calderon Y. Leider J. Hailpern S, et al. High-volume rapid HIV testing in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:749–755. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haukoos JS. Hopkins E. Eliopoulos VT, et al. Development and implementation of a model to improve identification of patients infected with HIV using diagnostic rapid testing in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1149–1157. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zetola NM. Klausner JD. Haller B. Nassos P. Katz MH. Association between rates of HIV testing and elimination of written consents in San Francisco. JAMA. 2007;297:1061–1062. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arbelaez C. Wright EA. Losina E, et al. Emergency provider attitudes and barriers to universal HIV testing in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Dowdy D. Rodriguez R. Hare CB. Kaplan B. Cost-effectiveness of targeted HIV screening in an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Torian LV. Wiewel EW. Continuity of HIV-related medical care, New York City, 2005–2009: Do patients who initiate care stay in care? AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:79–88. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchant RC. Waxman MJ. HIV screening in health care settings: Some progress, even more questions. JAMA. 2010;304:348–349. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haukoos JS. Hopkins E. Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA. 2010;304:284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zetola NM. Kaplan B. Dowling T, et al. Prevalence and correlates of unknown HIV infection among patients seeking care in a public hospital emergency department. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):41–50. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.San Francisco Department of Public Health. HIV/AIDS epidemiology annual report 2008. www.sfdph.org/dph/files/reports/RptsHIVAIDS/AnnlReport2008-20090630.pdf. [Mar 7;2011 ]. www.sfdph.org/dph/files/reports/RptsHIVAIDS/AnnlReport2008-20090630.pdf