Abstract

Study Design

A study of the morphometrical and histological changes of the intervertebral discs (IVDs) in biglycan (Bgn)-deficient mice.

Objective

In this study we investigate whether the absence of Bgn accelerates the degenerative process in mouse IVD.

Summary of Background Data

Proteoglycans and collagen fibrils are major components in the extracellular matrix (ECM) composition of IVD. The ECM of IVD contains several members of the small leucine repeat proteoglycans (SLRPs) family. Bgn is one member of SLRPs family, and showed a unique expression with age and degeneration in the human IVD. To date there have been no in vivo studies to see if SLRPs have a role in maintaining the structural integrity of IVD. To explore the functions of Bgn in the IVD, we examined discs in Bgn-deficient mice.

Methods

A total of 30 spine specimens were harvested from wild-type (WT) and Bgn-deficient mice. Five specimens for each genotype at 4, 6, and 9 months old were examined in the experiments. Morphometrical and histological analysis of the IVD were performed. Histological gradings were performed separately on nucleus pulposus (NP), annulus fibrosus (AF), and end plate (EP) according to the classification system proposed by Boos et al.

Results

The Bgn-deficient mice exhibited progressive decreases of NP area with age, which were representative changes consistent with disc degeneration. We found that Bgn-deficient mice developed an early onset of disc degeneration compared to WT mice. The degenerative scores of Bgn-deficient mice were significantly higher than those of WT mice at 4 and 9-month-old. High scores for NP and AF in Bgn-deficient mice significantly affected the difference in total degenerative scores at 9 months of age.

Conclusion

Bgn deficiency significantly accelerated disc degeneration.

Keywords: intervertebral disc, biglycan, knock-out mouse, degeneration, SLRP (small leucine rich repeat proteoglycan)

Introduction

The relationship between human intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and low back pain remains unclear. There is no correlation between the severity of pain and the severity of disc degeneration 1, 2, but deterioration of IVD with loss of normal composition could change the mechanical load acting on the IVD itself and surrounding structures such as facet joints, ligaments, and paravertebral muscles, which serve to stabilize the spine, leading ultimately to the development of symptomatic degenerative disorders such as disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Degenerative changes of IVD that occur as a pathologic process are similar to those that occur with normal aging 3. Pathologic features unique to degeneration and not aging have not been identified. In that sense, degeneration of IVD might be a premature or early onset of the aging process.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) composition of IVD is similar to articular cartilage. Proteoglycans and collagen fibrils are major components in the ECM of articular cartilage. The ECM of articular cartilage contains several members of the small leucine repeat proteoglycans (SLRPs) family 4. SLRPs form a specific subgroup with the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) superfamily of proteins, and can be divided into 3 classes based on similarity of genomic organization and core protein structure 5. Biglycan (BGN) belongs to a class I SLRP. Several SLRPs bind to TGF-βs, collagens, and other matrix molecules 6. Bgn-deficient mice and fibromodulin (Fmd) -deficient mice developed premature osteoarthritis (OA) 7. The development of OA by those mice suggests that mutations in the SLRPs might be predisposing genetic factors 8. Recently, asporin, one member of a class I SLRP, was demonstrated to be a susceptible gene for OA of knee and hip joints in the Japanese population 9. Asporin acts as a crucial modulator of TGF-β, a key growth factor in cartilage metabolism.

Temporal and spatial expressions of some SLRPs were also demonstrated in Ovine 10 and human IVD 11–13. The level of BGN expression showed a unique pattern with age and degeneration in the human IVD. In a study of human lumbar IVD with normal appearance, the amount of BGN has been found to be highest in the outer AF, and was greatly reduced or absent in the NP 11, 12. The progressive loss of BGN in the AF has been observed with age 12, 13. BGN has been found to exist in different forms, glycosaminoglycan-containing (glycanated) forms and non-glycanated forms 14. The non-glycanated BGN has been found to be relatively predominant with age in the IVD 11, 14. On the other hand, in a study of the degenerated lumbar IVD obtained at surgery, the content of BGN and decorin (DCN) in the AF was significantly elevated at early stages of degeneration, and then declined in severely degenerated stage 12, 13. In the NP, the contents of the SLRPs (BGN, DCN, and FMOD) showed a decrease at early stages of degeneration. The levels of DCN and FMOD continued to decrease progressively with increasing grade of degeneration. However, the content of BGN bounced back to normal levels even in advanced stage 13.

Previous studies have shed light on the different BGN expression level of IVD between normal aging and degenerative process. To explore the functions of Bgn in the homeostasis of IVD, we examined discs in Bgn-deficient mice. Specifically, we asked whether the absence of Bgn accelerates the degenerative process in IVD in a similar fashion to that seen in the articular cartilage of SLRPs (Bgn and/or Fmd)-deficient mice 7.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals and tissue preparation

All animal studies were performed according to the institutionally approved protocol for animal use. Bgn-deficient mice were generated by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells as described previously 15. All mice were maintained in a hybrid (C57B6/129) genetic background. We used male mice for experimental animals because Bgn gene is located on the X chromosome and absent from the Y chromosome. Hereafter, Bgn-deficient mice will be referred to as Bgn−/0 mice. DNA was isolated from tail samples, and the genotype of the wild-type (WT) and Bgn−/0 mice was determined by PCR as described previously 16. PCR products were separated and resolved on 2% agarose gels. The successful genetic deletion in Bgn−/0 mice was confirmed by the absence of Bgn mRNA and Bgn protein in Bgn−/0 mice 15.

A total of 30 spine specimens were harvested from male mice of each genotype (WT, and Bgn−/0). Five specimens for each genotype at 4, 6, and 9 months old were examined in the experiments. Isolated spines were fixed for 2 weeks in 4% paraformaldehyde, and decalcified for 2 weeks in 20% EDTA.

Morphometrical analysis of the nucleus pulposus

All the decalcified lumbar spines, before processing to histological preparation, were underwent lateral plain radiography using a high potential generator (model DHF-155H; Hitachi Medical Corp., Tokyo, Japan), with a collimator-to-film distance 70cm, exposure of 40mAs, and penetration power of 60kV. The radiographs, taken several times on each specimen, underwent morphometrical analysis under 100× magnification (Figure 1A). The radiolucent area between the radiopaque margins of the end plate (EP), which representing the shape of the nucleus pulposus (NP), were measured using Doctor File Viewer version.1.02.0 (Finggal Link Co. LTD, Tokyo, Japan). All radiographs were measured independently by 2 authors (T.F and K.I) in double blind fashions.

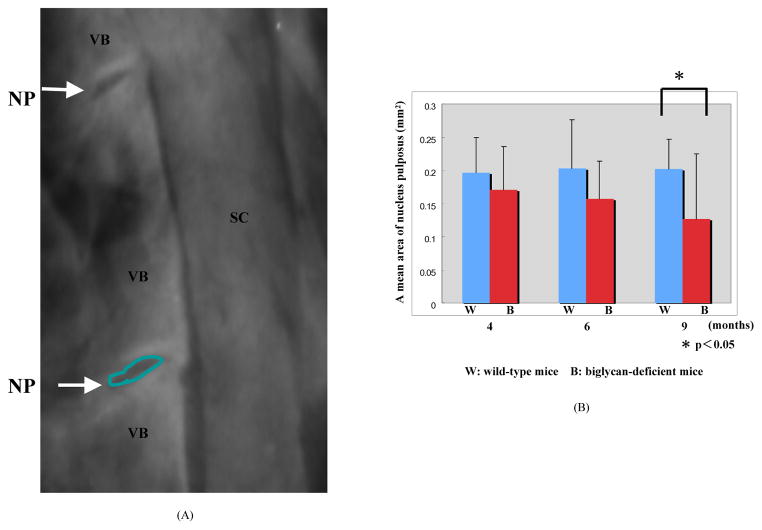

Figure 1.

Morphometrical analysis of the nucleus pulposus (NP). A, representative picture with the outline of the radiolucent area between the radiopaque margins of the end plate (EP). VB (vertebral body) SC (spinal cord); B, the mean and standard deviation of NP area are shown. Biglycan-deficient mice at 9-month-old had a significantly reduced size compared to age-matched wild-type mice (P<0.05).

Histological analysis of the lumbar disc

The decalcified spines were carefully cleaved in a sagittal plane. They were dehydrated in graded alcohols and xylene, embedded in paraffin, and cut serially into 4μm sagittal sections. Midsagittal sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and alcian blue-PAS. All specimens were evaluated at L1/L2 disc level microscopically. The IVD degeneration was scored according to the classification system proposed by Boos et al 17 (Table I). They developed a classification system for grading the histological features of age-related changes in the lumbar disc. Histological gradings were performed separately on nucleus pulposus (NP), annulus fibrosus (AF), and end plate (EP). Their classification system was based on an extensive semiquantitative histological analysis (NP/AF 0-22, EP 0-18, total 0-40). With this scoring system, a higher score indicated a more severe stage of disc degeneration. The sections underwent double blind examinations by 2 authors independently (T. F and K. I).

Table I.

Classification system for grading age-related histologic changes in the intervertebral disc and endplate

| Nucleus pulposus/Annulus fibrosus | Endplate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| cells (chondrocyte proliferation) | (0~6) | cells | (0~4) |

| mucous degeneration | (0~4) | cartilage disorganization | (0~4) |

| cell death | (0~4) | cartilage cracks | (0~4) |

| tear and cleft formation | (0~4) | microfracture | (0~2) |

| granular changes | (0~4) | new bone formation | (0~2) |

| bony sclerosis | (0~2) | ||

|

| |||

| total 0~22 points | total 0~18 points Boos N, et al. 2002 |

||

Proteoglycan (PG) density was quantified by image analysis on midsagittal sections as described by Van der Kraan et al 18. The tissue sections were stained with Safranin O/Fast green FCF for the detection of PG depletion. Images were captured using a color CCD camera (DFC420C; Leica, Cambridge, UK). A circle of 60 × 60 pixels was measured for each NP and calcified EP at fixed portions (2 zones for the NP and 6 zones for the calcified EP as indicated in Figure 3). The amount of red staining was measured using Image J 1.38X (developed by the US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and was presented as a unitless number.

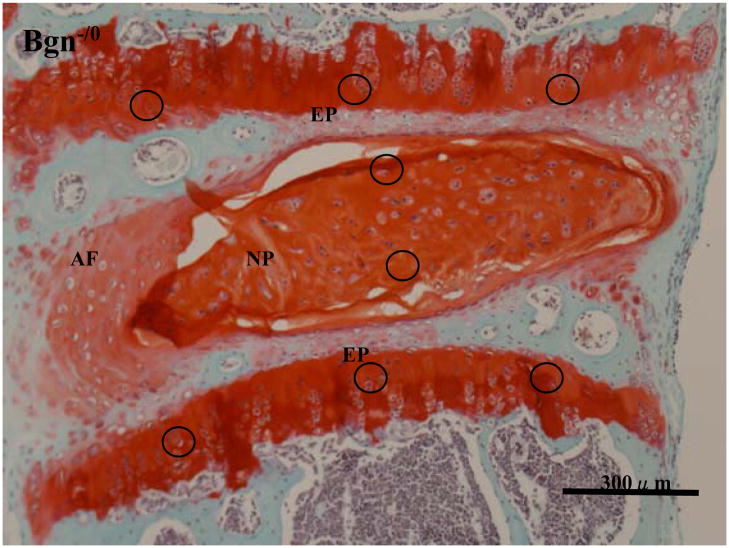

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of intervertebral disc (IVD) from Bgn-deficient mouse at 6 months of age, Safranin O/Fast green FCF staining. NP: nucleus pulposus, AF: annulus fibrosus, EP: end plate

Losses of notochordal cells associated with proliferation of chondrocyte-like cells are seen in the NP.

A circle of 60×60 pixels were measured at fixed portions, anterior 1/3, middle 1/3, and posterior 1/3 for the upper and lower calcified EP (total 6 zones). For the NP, 2 fixed portions, upper-middle and lower middle zone, were measured.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between WT and Bgn−/0 mice at different developmental steps for the morphometry of NP and the total degenerative scores of IVD. The differences among means of data at 4, 6, and 9 months old were analyzed for each genotype using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) as a post hoc test. Furthermore, the total degenerative scores of each genotype were analyzed with 2-way ANOVA for 2 factors, the developmental steps (4, 6, and 9 months of age) and a portion of the disc (NP/AF or EP). Statistical analysis was performed using the Statview (version 4.02; SPSS, Chicago, IL) program package. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Morphometry of the nucleus pulposus

The size of NP did not appear to differ between WT and Bgn−/0mice at 4-month-old (mean ± standard deviation(SD); WT 0.19 ± 0.054mm2, Bgn−/0 0.17 ± 0.064mm2) and 6-month-old (WT mice 0.20 ± 0.073mm2, Bgn−/0 mice 0.15 ± 0.057mm2) (Figure 1B). Bgn−/0 mice at 9-month-old, in contrast, had a significantly reduced size compared to age-matched WT mice (Figure 1B; WT 0.2 ± 0.045mm2, Bgn−/0 0.13 ± 0.098mm2, P<0.05). The size of NP did not show significant changes over time in WT mice. In contrast, it showed a trend for decrease in Bgn−/0 mice with ages, although, the differences among means of data at 4, 6, and 9-month-old were not significant.

Histological features

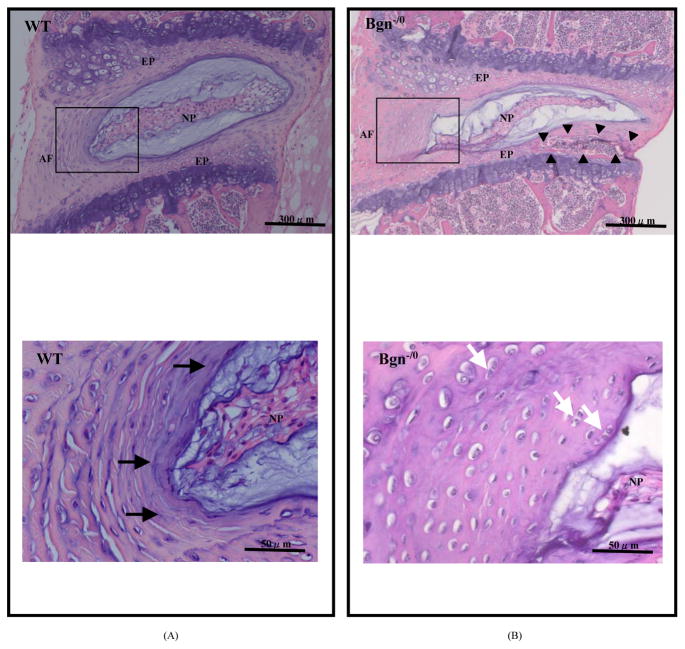

At 4 months of age, early signs of degeneration were present in the inner AF of mutant mice. The fibroblastic elongated cell shape seen in WT mice (Figure 2A) became a small rounded cell resembling a chondrocyte in Bgn−/0 mice (Figure 2B). Cell density increased and small-size clones were frequently visible. New bone formation was frequently seen in the cartilaginous EP of Bgn−/0 mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of the intervertebral disc (IVD) from 4-month-old mouse, hematoxylin and eosin staining. NP: nucleus pulposus, AF: annulus fibrosus, EP: end plate, WT: wild-type mouse, Bgn−/0: Bgn-deficient mouse. Note small rounded cells resembling chondrocytes (white arrows) proliferate in the inner AF from Bgn−/0 mouse (B), while IVD from WT mouse shows fibroblastic elongated cells (black arrows) in the inner AF (A). New bone formation (arrowheads) is seen in the cartilaginous EP of Bgn−/0 mice (B).

At 6 months of age, degenerative changes were evident in IVDs of all mutant mice. The NP of Bgn−/0 mice exhibited an early loss of notochordal cells associated with a proliferation of chondrocyte-like cells (Figure 3). A substantial increase of cell density associated with a small number of cell deaths became evident in NP and AF. In some of the Bgn−/0 mice, scar formation in the NP was noted (data not shown).

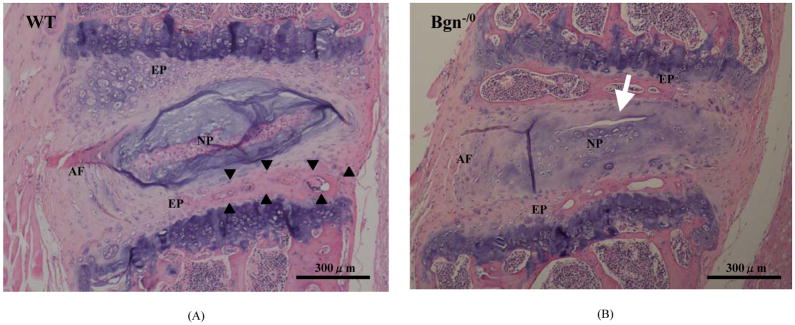

At 9 months of age, advanced degenerative changes were present in the NP and AF of Bgn−/0 mice (Figure 4B). In the NP, there was a regression in the number of chondrocytes, whereas the number of small-size clones increased. Boundaries between the NP and inner AF became less distinct. Tears and clefts of NP and AF were seen abundantly. Mucous degeneration was frequently seen in the NP of Bgn−/0 mice, but was not seen in that of WT mice (data not shown). The structural changes of the AF and EP in WT mice were similar to those seen in Bgn−/0 mice at 4 months. In the AF of WT mice, the cell shape became a small rounded cell resembling a chondrocyte (Fig 4A). Furthermore, new bone formation was identified in the cartilaginous EP of WT mice at 9-month-old (Figure 4A), which was frequently seen in the cartilaginous EP of Bgn−/0 mice at 4-month-old (Figure 2B).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of the intervertebral disc from 9-month-old mouse, hematoxylin and eosin staining. NP: nucleus pulposus, AF: annulus fibrosus, EP: end plate, WT: wild-type mouse, Bgn−/0: Bgn-deficient mouse. In the AF of WT mouse, the shapes of cells become rounded, resembling chondrocytes. New bone formation is identified in the cartilaginous EP, which is frequently seen in the EP of Bgn−/0 mouse at 4-month-old (A). In the NP of Bgn−/0 mouse, there is a regression in the number of chondrocytes. Arrow indicates cleft in the NP (B).

In this study microfracture and bony sclerosis of the vertebral endplate adjacent to cartilage EP were not seen obviously in Bgn−/0 mice, as well as in any WT mice.

Image analysis of Safranin-O staining showed changes of proteoglycan (PG) density of the NP and EP with age. The PG density of NP increased in WT mice at 6-month-old and showed sustained level at 9 months, whereas it showed a gradual decrease in Bgn−/0 mice (Table II). The PG density of calcified EP did not show significant changes over time and no differences were noted between WT mice and Bgn−/0 mice.

Table II.

Average density of Safranin O staining for nucleus pulposus and end plate in wild-type and biglycan-deficient mice

| WT

|

Bgn−/0 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months | 6 months | 9 months | 4 months | 6 months | 9 months | |

| Nucleus pulposus | 104.86 ± 86.84 | 182.98 ± 102.99 | 175.95 ± 98.94 | 189.39 ± 58.83 | 159.37 ± 85.14 | 107.97 ± 73.46 |

| Endplate | 252.92± 4.08 | 252.13 ± 6.14 | 254.77 ± 0.39 | 253.26 ± 3.03 | 250.53 ± 7.33 | 254.67 ± 0.65 |

Values are presented as means ± SD; n=5 intervertebral discs per genotype and time point.

WT: wild-type mice, Bgn−/0: biglycan-deficient mice

Statistical analysis (Table III, Figure 5)

Table III.

Histological grading for nucleus pulposus/annulus fibrosus and end plate in wild-type and biglycan-deficient mice

| WT

|

Bgn−/0 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months | 6 months | 9 months | 4 months | 6 months | 9 months | |

| Nucleus pulposus/Annulus fibrosus | ||||||

| Chondrocyte proliferation | 0 | 0.6±0.89 | 0.8±1.10 | 2.0±0.00 | 2.2±0.45 | 2.6±0.55 |

| Mucous degeneration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6±0.55 |

| Cell death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6±0.89 | 2.2±0.84 |

| Tear/cleft | 0.2±0.45 | 0.2±0.45 | 0.2±0.45 | 1.0±0.71 | 0.8±1.30 | 2.0±0.71 |

| Granular changes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6±0.89 | 1.6±1.14 |

| Endplate | ||||||

| Cell proliferation | 0.2±0.45 | 0.8±0.45 | 1.2±0.45 | 1.0±0.00 | 1.0±0.00 | 0.8±0.45 |

| Cartilage disorganization | 0.6±0.55 | 1.0±0.00 | 1.4±0.55 | 1.8±0.45 | 1.8±0.45 | 1.8±0.45 |

| Cartilage cracks | 0.8±0.45 | 1.4±0.55 | 1.0±0.00 | 1.0±0.00 | 0.8±0.45 | 1.0±0.00 |

| Microfracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New bone formation | 0.8±0.45 | 0.4±0.55 | 0.8±0.45 | 1.0±0.00 | 0.8±0.45 | 0.8±0.45 |

| Bony sclerosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values are presented as means ± SD; n=5 intervertebral discs per genotype and time point.

WT: wild-type mice, Bgn−/0: biglycan-deficient mice

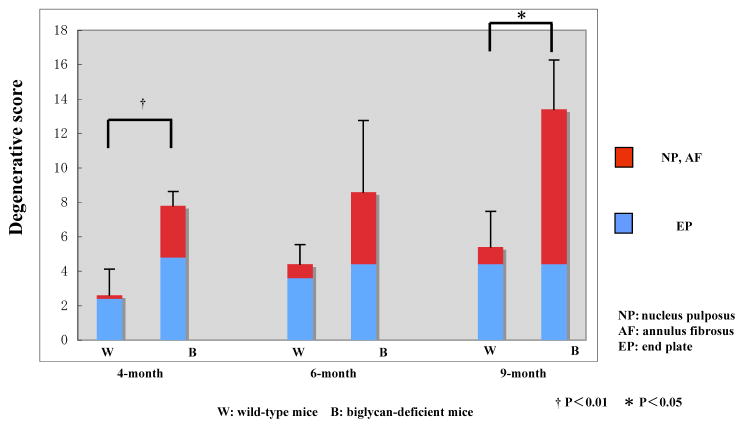

Figure 5.

Histological gradings for intervertebral disc in wild-type (WT) and Bgn-deficient (Bgn−/0) mice. Total degenerative scores of Bgn−/0 mice are significantly higher than those of WT mice (p=0.0037 at 4M, p=0.098 at 6M, p=0.018 at 9M). The degenerative scores of WT and Bgn−/0 mice significantly increase with age. High scores of the NP and AF in Bgn−/0 mice significantly affect the difference in total degenerative scores at 9 months of age.

The Student’s t-test revealed that total degenerative scores of Bgn−/0 mice were significantly higher than those of WT mice (p=0.0037 at 4M, p=0.098 at 6M, p=0.018 at 9M). The 1-way ANOVA indicated that there were significant differences among means of data at 4, 6 and 9-month-old for Bgn−/0 mice (WT: p=0.042, Bgn−/0: p=0.018). Further analysis using the Fisher’s PLSD test revealed that the degenerative scores of 9-month-old WT mice were significantly higher than those of 4-month-old WT mice (p=0.0013). In Bgn−/0 mice, the degenerative scores at 9-month-old mice were significantly higher than those at each 4, and 6-month-old-mice (4M versus 9M: P=0.006, 6M versus 9M: P=0.037). The 2-way ANOVA demonstrated that high scores of NP/AF in Bgn−/0 mice significantly affected the difference in total degenerative scores at 9 months of age. In WT mice, however, each score of NP/AF and EP did not affect the difference in total degenerative scores at every age examined. There were no significant intra and inter-observer differences.

Discussion

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of intervertebral disc (IVD) contains several members of the small leucine repeat proteoglycans (SLRPs) family 11–13. To date there have been no in vivo studies to see if SLRPs have a role in maintaining the structural integrity of IVD. Biglycan (BGN) is one member of the SLRPs family. To explore the function of Bgn in the homeostasis of IVD, we investigated IVD in Bgn-deficient (Bgn−/0) mice. In the soft tissue radiographic measurements, the NP area did not show significant changes over time in WT mice. In contrast, it exhibited progressive decreases in Bgn−/0 mice with age. Histological analysis revealed that Bgn−/0 mice at 4 months of age exhibited apparent proliferation of chondrocyte-like cells in the AF. Furthermore, in the NP at 6 months of age for these mice, there was an early loss of notochordal cells associated with a proliferation of chondrocyte-like cells. In the NP at 9 months of age, these mutant mice exhibited a decrease in the number of chondrocyte-like cells. Proteoglycan (PG) density of the NP showed a gradual decrease in Bgn−/0 mice with age, and with increasing grade of degeneration. The scoring system confirmed that IVD of Bgn−/0 mice were in a more advanced degenerative state than that of wild-type mice at every age examined. The Bgn deficiency significantly accelerated disc degeneration.

There are several possible mechanisms whereby the absence of Bgn accelerates the degeneration of IVD.

A possible mechanism is that loss of Bgn might cause structural instability within ECM, leading to weakness and instability of IVD as a whole. Wiberg et al observed in detail the interaction of Dcn and Bgn with other components in the cartilaginous ECM extracellular matrix of Swarm rat chondrosarcoma 19. They showed that Dcn/Bgn formed complexes with matrillin-1, and these complexes acted as linkages between collagen VI microfibrils in a pericellullar matrix and collagen II fibrils or aggrecan in a territorial matrix. Thus, they demonstrated that an important role of LRR-proteoglycan is to serve as adapter proteins connecting macromolecular networks in the cartilage ECM. Deficiency of Bgn in the NP might destabilize the macromolecular assembly, and compromise the ability of NP to disperse compressive forces. This condition could render the IVD more vulnerable to damage, and could evoke premature degenerative disease.

Another possible explanation is that loss of Bgn in the AF and fibrous connective tissues surrounding IVD could increase mechanical stress on IVD, leading to premature degeneration. Bgn is thought to play a critical role in collagen fibrillogenesis. Structural abnormalities in collagen fibrils were precisely observed in the tendons of Bgn−/0 mice 7. These mice contained larger and more irregular collagen fibers. Similar changes could occur in fibrous tissues, including ligaments, muscles, and AF, which support the spinal column. Although the properties of anterior and posterior longitudinal ligament are not tested biomechanically in Bgn−/0 mice, mechanical failure of the ligaments and the AF might destabilize the spinal column, and allow abnormal impaction to act on IVD, ultimately triggering premature degeneration.

Another possible mechanism is that loss of Bgn could inhibit or buffer transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which is a well-known growth factor that promotes the production of ECM in osteo-chondral tissues. Hildebrand et al showed that each of the 3 SLRPs (DCN, BGN, and FMOD) binds to TGF-β via their core proteins with similar binding activities 20. Recent data suggest that the collagen-bound DCN sequesters and inactivates TGF-β 21. In a culture system of calvarial osteoblastic cells, Chen et al demonstrated that Bgn modulates BMP-stimulated osteoblastic differentiation 22. They proposed a model in which Bgn and Dcn competitively bind BMP/TGF-β, and balance the supply of those growth factors to the target cells. Bgn promotes the binding of BMP/TGF-β to their receptors, while Dcn suppresses it. Deficiency of Bgn, thus, might promote these growth factors to bind exclusively to Dcn, repress signaling transduction of BMP/TGF-β, and ultimately impair osteoblastic differentiation. A similar mechanism could be working in the chondrocytes of IVD, and the absence of Bgn might repress the signaling transduction of TGF-β, ultimately leading to a suppressed response for repairing ECM.

There are many reports evaluating the relationship between IVD degeneration and bone mineral density (BMD) of the vertebral body 23–26. There is evidence for an inverse association between the grades of IVD degeneration and BMD-people with advanced IVD degeneration having a higher BMD than those without. The mechanism is thought that as vertebral BMD increases, mechanical stress acting on IVD increases, subsequently accelerating disc degeneration. Bgn−/0 mice in this study showed decreased BMD and bone mass with age compared to age matched controls 15. Therefore, in these mutant mice, abnormal bone metabolism itself is less likely to result in the premature disc degeneration.

Boos et al developed a practical classification system for disc aging or premature aging (degeneration) based on an analysis of human lumbar intervertebral disc 17. Histological gradings were performed separately for NP/AF and EP (Table I). The extents of the histological variable are assessed semi-quantitatively for 5 histological markers (cell proliferation, mucoid degeneration, cell death, tears and clefts, and granular changes) in the NP/AF and 6 markers (cell proliferation, cartilage disorganization, cracks, microfracture, new bone formation, and bony sclerosis) in the EP. We applied their classification system to evaluate mice discs. During the evaluation of WT mice specimens, we think that their system could be suitable for describing histological changes in mouse IVD with age. However, in the evaluation of 9-month-old mice, no degenerative findings of the later stage of human spondylosis, such as subchondral sclerosis and osteophytes formation in the vertebral body, were seen for Bgn−/0 mice as well as WT mice. Longer-term observation is necessary to see if the Bgn mutant mice develop a further degenerative progression in the IVD.

Sobajima et al 27 have shown a progressive decrease of NP area with time in a rabbit model of IVD degeneration with use of MRI. The Bgn−/0 mice showed representative changes consistent with disc degeneration (Figure 1). Studies on the IVD of Bgn−/0 mice would be useful for understanding molecular processes that lead to early onset of IVD degeneration.

Key Points.

To date there have been no in vivo studies to see if the small leucine repeat proteoglycans (SLRPs) have a role in maintaining the structural integrity of intervertebral disc; therefore, we examined discs in biglycan (Bgn)-deficient mice to explore the functions of SLRPs in vivo.

Bgn-deficient mice exhibited progressive decreases of NP area with age, which were representative changes consistent with disc degeneration.

Bgn-deficient mice developed an early onset of disc degeneration compared to wild-type mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Eiko Saito for her technical assistance with tissue processing. We also thank Mr. Takashi Kawamura for his technical assistance in morphometrical analysis.

This work was supported by a grant from the Yamagata Health Support.

The abbreviations used are

- EDTA

ethylenedinitrilotetraacetic acid

- PAS

periodic acid Schiff

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernon-Rpberts Barrie. Age-related and degenerative pathology of intervertebral discs and apophyseal joints. In: Jayson MIV, editor. The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinegård D, Larsson T, Sommarin Y, et al. Two novel matrix proteins isolated from articular cartilage show wide distributions among connective tissues. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13866–13872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi Y, Mann DM, Ruoslahti E. Negative regulation of transforming growth factor β by the proteoglycan decorin. Nature. 1990;346:281–284. doi: 10.1038/346281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ameye L, Aria D, Jepsen K, et al. Abnormal collagen fibrils in tendons of biglycan/fibromodulin-deficient mice lead to gait impairment, ectopic ossification, and osteoarthritis. FASEB J. 2002;16:673–680. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0848com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ameye L, Young MF. Mice deficient in small leucine-rich proteoglycans: novel in vivo models for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, muscular dystrophy, and corneal diseases. Glycobiology. 2002;12:107R–116R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kizawa H, Kou I, Iida A, et al. An aspartic acid repeat polymorphism in asporin inhibits chondrogenesis and increases susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:138–144. doi: 10.1038/ng1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melrose J, Ghosh P, Taylor TKF. A comparative analysis of the differential spatial and temporal distributions of the large (aggrecan, versican) and small (decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin) proteoglycan of the intervertebral disc. J Anat. 2001;198:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19810003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnstone B, Markopoulos M, Neame P, et al. Identification and characterization of glycanated and non-glycanated forms of biglycan and decorin in the human intervertebral disc. Biochem J. 1993;292:661–6. doi: 10.1042/bj2920661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inkinen RI, Lammi MJ, Lehmonen S, et al. Relative increase of biglycan and decorin and altered chondroitin sulfate epitopes in the degenerating human intervertebral disc. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:506–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo GC, Juan DRS, Turumella V, et al. Changes in mRNA and protein levels of proteoglycans of the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus during intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2002;27:2212–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roughley PJ, White RJ, Magny MC, et al. Non-proteoglycan forms of biglycan increase with age in human articular cartilage. Biochem J. 1993;295:421–6. doi: 10.1042/bj2950421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu TS, Bianco P, Fisher LW, et al. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nature Genetics. 1998;20:78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen XD, Shi S, Xu T, et al. Age-related osteoporosis in biglycan-deficient mice is related to defects in bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:331–340. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boos N, Weissbach S, Rohrbach H, et al. Classification of age-related changes in lumber intervertebral discs. Spine. 2002;27:2631–2644. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Kraan PM, Lange J, Vitters EL, et al. Analysis of changes in proteoglycan content in murine articular cartilage using image analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1994;2:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiberg C, Klatt AR, Wagener R, et al. Complexes of matrilin-1 and biglycan or decorin connects collagen VI microfibrils to both collagen II and aggrecan. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37698–37704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildebrand A, Romarís M, Rasmussen LM, et al. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin, and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor β. Biochem J. 1994;302:527–534. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schönherr E, Broszat M, Brandan E, et al. Decorin core protein fragment Leu1 55-Val 260 interacts with TGF-β but dose not compete for decorin binding to type I collagen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:241–248. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen XD, Fisher LW, Robey PG, et al. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan biglycan modulates BMP-4-induced osteoblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2004;18:948–958. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0899com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harada A, Okuizumi H, Miyagi N, et al. Correlation between bone mineral density and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 1998;23:857–862. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyakoshi N, Itoi E, Murai H, et al. Inverse relation between osteoporosis and spondylosis in postmenopausal women as evaluated by bone mineral density and semiquantitative scoring of spinal degeneration. Spine. 2003;28:492–495. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048650.39042.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanjo Y, Morio Y, Nagashima H, et al. Correlation between bone mineral density and intervertebral disk degeneration in pre- and potmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;21:22–27. doi: 10.1007/s007740300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pye SR, Reid DM, Adams JE, et al. Radiographic features of lumbar disc degeneration and bone mineral density in men and women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:234–238. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobajima S, Kompel JF, Kim JS, et al. A slowly progressive and reproducible animal model of intervertebral disc degeneration characterized by MRI, X-ray, and histology. Spine. 2005;30:15–24. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000148048.15348.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]