Abstract

The roles of muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptors in perirhinal cortex in object recognition memory were compared. Rats' discrimination of a novel object preference test (NOP) test was measured after either systemic or local infusion into the perirhinal cortex of the nicotinic receptor antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA), which targets alpha-7 (α7) amongst other nicotinic receptors or the muscarinic receptor antagonists scopolamine, AFDX-384, and pirenzepine. Methyllycaconitine administered systemically or intraperirhinally before acquisition impaired recognition memory tested after a 24-h, but not a 20-min delay. In contrast, all three muscarinic antagonists produced a similar, unusual pattern of impairment with amnesia after a 20-min delay, but remembrance after a 24-h delay. Thus, the amnesic effects of nicotinic and muscarinic antagonism were doubly dissociated across the 20-min and 24-h delays. The same pattern of shorter-term but not longer-term memory impairment was found for scopolamine whether the object preference test was carried out in a square arena or a Y-maze and whether rats of the Dark Agouti or Lister-hooded strains were used. Coinfusion of MLA and either scopolamine or AFDX-384 produced an impairment profile matching that for MLA. Hence, the antagonists did not act additively when coadministered. These findings establish an important role in recognition memory for both nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in perirhinal cortex, and provide a challenge to simple ideas about the role of cholinergic processes in recognition memory: The effects of muscarinic and nicotinic antagonism are neither independent nor additive.

Much evidence indicates that the perirhinal cortex is critically involved in object recognition memory (for reviews, see Murray and Bussey 1999; Brown and Aggleton 2001; Mumby 2001; Aggleton and Brown 2006; Mumby et al. 2007; Aggleton et al. 2010; Brown et al. 2010; Winters et al. 2010). Recognition memory is impaired by lesions of the perirhinal cortex (Zola-Morgan et al. 1989; Gaffan and Murray 1992; Meunier et al. 1993, 1996; Mumby and Pinel 1994; Ennaceur et al. 1996; Winters et al. 2004) or by local perirhinal infusions of glutamatergic receptor antagonists (Winters and Bussey 2005; Barker et al. 2006b).

The cholinergic system is widely hypothesized to play a prominent role in mechanisms of memory and attention (for reviews, see Voytko 1996; Sarter and Bruno 1997; Easton and Parker 2003; Sarter et al. 2003; Hasselmo and Giocomo 2006; Hasselmo and Stern 2006; Dani and Bertrand 2007). Nicotinic and muscarinic receptors are located on neurons in the cerebral cortex, including perirhinal cortex (Saleem et al. 2007). Nicotinic receptor subunits form ligand-gated ion channels (Sargent 1993), while muscarinic receptors are G-protein linked (Wess 1993). Most nicotinic receptor subtypes are permeable to Na+ and K+ ions, but the alpha-7 (α7) subtype is of particular interest because it is also permeable to Ca2+ ions (Seguela et al. 1993) and has been linked to second messenger pathways important in plasticity and memory formation (Bitner et al. 2007). Indeed, it has been claimed that α7 nicotinic receptors play a role in hippocampal LTP (Matsuyama et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2006) and the nicotinic antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) that acts against α7, as well as other nicotinic receptors (Mogg et al. 2002), has been shown to inhibit hippocampal LTP induction (Freir and Herron 2003; Chen et al. 2006). In perirhinal cortical slices, the broad spectrum muscarinic receptor antagonist scopolamine blocks LTD but not LTP (Warburton et al. 2003) and application of the cholinomimetic carbachol induces a long-lasting depression (Massey et al. 2001). The role of nicotinic, including α7 receptors in perirhinal plasticity, is unknown.

It has been reported previously that scopolamine can impair familiarity discrimination (Huston and Aggleton 1987; Ennaceur and Meliani 1992; Bartolini et al. 1996; Besheer et al. 2001; Norman et al. 2002; Warburton et al. 2003; Winters et al. 2007), including when infused directly into the perirhinal cortex in monkeys (Tang et al. 1997) or rats (Abe and Iwasaki 2001; Warburton et al. 2003; Winters et al. 2007). However, studies of nicotinic receptors have chiefly investigated agonist actions and none have determined the role of antagonists within the perirhinal cortex (Van Kampen et al. 2004; Boess et al. 2007; Pichat et al. 2007). In the experiments reported here, the effect upon recognition memory of MLA, which strongly antagonizes α7 nicotinic but may also antagonize other nicotinic receptors (Mogg et al. 2002), has been compared with that of the broad-spectrum muscarinic antagonist scopolamine. The actions were found to doubly dissociate across 20-min and 24-h time delays. As this result was unexpected and the effect of scopolamine was not in accord with a previous study, further experiments were performed with AFDX-384 (at a concentration designed to act also as a broad-spectrum muscarinic antagonist) (Dorje et al. 1991), scopolamine using variants of the basic experimental conditions, and the selective M1 muscarinic antagonist pirenzepine. Additionally, to determine whether impairment at both 20 min and 24 h could be produced by combining muscarinic with nicotinic antagonism, the effects of coadministration were sought. The findings established an unusual double dissociation in the effects of muscarinic and nicotinic antagonism that provides a challenge to simple ideas about the role of cholinergic processes in recognition memory.

Results

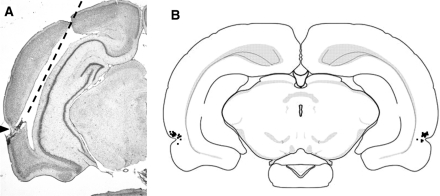

To establish the role of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors in recognition memory, the effects of systemic administration or local infusions of the nicotinic antagonist MLA or muscarinic antagonists into the perirhinal cortex were determined on the rats' preferential exploration of a novel compared with a familiar object. Systemic injections or perirhinal infusions (see Fig. 1B for infusion sites) of vehicle or antagonist were made 30 min (systemic) or 15 min (local infusion) prior to the acquisition phase of the object recognition test with the choice (test) phase being at a delay of either 20 min or 24 h. The discrimination ratio (DR) at test was calculated by dividing the difference in time exploring the novel and the familiar object by the time taken exploring both objects.

Figure 1.

Site of intracerebral infusions into the perirhinal cortex. (A) Cresyl violet-stained section showing the track mark of the guide cannula (20° from vertical—see dashed line) and the infusion site within the perirhinal cortex (rhinal sulcus is marked by the black triangle). (B) Reconstructed individual infusion sites from the 25 animals included in the analysis from Experiments 1–5 shown on a representative brain section at −5.8 with respect to bregma (Paxinos and Watson 1998). Black squares indicate the tip of the guide cannula (note some symbols may overlap). All cannulae were accurately located in the perirhinal cortex.

All rats under control conditions showed significant discrimination at all time intervals (t-tests, P ≤ 0.05). Additionally, the total time exploring objects in the acquisition or choice phases showed no significant differences dependent on whether the animals had received vehicle or cholinergic antagonists (Table 1).

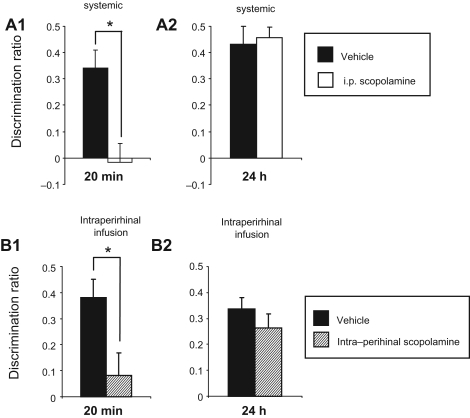

Table 1.

Exploration of animals in the acquisition and choice phases

Values shown are mean time exploring both objects in seconds (SEM) for vehicle or drug at each of the time-points investigated. For acquisition trials, three factor ANOVA (treatment, route/dose, delay) for Experiments 1 and 2, or two factor ANOVA for Experiments 3, 4A, or 4B, (treatment, delay) revealed no significant effects across any of the experimental groupings. Similarly, for choice trials, three factor ANOVA and two factor ANOVA revealed no significant effects across any of the experimental groupings.

Experiment 1 investigated the effect of nicotinic receptor antagonism.

Experiment 1: Object recognition memory following administration of the nicotinic receptor antagonist MLA

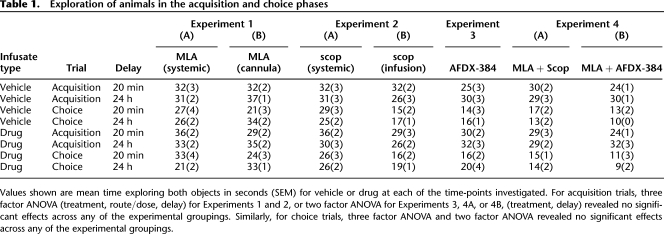

Figure 2 shows that MLA impaired recognition memory at a delay of 24 h, but not at a delay of 20 min, whether administration was systemic (87.5 µg/kg) or local via cannula infusion (0.0875 ng/µL) into the perirhinal cortex.

Figure 2.

Effect of methyllycaconitine (MLA) on object recognition memory at 20-min or 24-h delays tested in Dark Agouti rats in the arena. (A) Effect of systemic injection of MLA (87.5 µg/kg, ip). MLA impaired memory after a 24-h (A2) but not a 20-min (A1) delay. (B) Effect of intraperirhinal infusion (0.0875 ng/µL) of MLA. Again, MLA impaired memory after a 24-h (B2), but not after a 20-min (B1) delay. (*) P < 0.05.

Analyzing across all of the MLA conditions, three factor ANOVA (delay [20 min or 24 h], administration route [systemic injection or intracerebral infusion], treatment [vehicle or drug]) revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(1,40) = 6.62, P = 0.01), and a significant interaction of treatment by delay (F(1,40) = 4.61, P = 0.04). Data for the two delays were therefore analyzed separately.

For the 20-min delay tests, two factor ANOVA (administration route, treatment) showed no significant effect of treatment (F(1,20) < 1, P = 0.8) and no significant interaction of administration route by treatment (F(1,20) < 1, P = 0.4). The MLA-treated animals showed significant discrimination in the test (DR > 0: t-test, systemic injection: P = 0.001; intracerebral infusion: P = 0.001).

For the 24-h delay tests, two factor ANOVA (administration route, treatment) showed a significant effect of treatment (F1,20 = 15.17, P = 0.001) and no significant interaction of administration route by treatment (F(1,20) = 2.00, P = 0.2). Post-hoc analysis for the 24-h tests with ANOVAs showed a significant impairment in the MLA-treated rats compared with controls (systemic injection: F(1,9) = 7.74, P = 0.02; intracerebral infusion: F(1,11) = 7.48, P = 0.02); the MLA-treated animals did not show significant discrimination in the test (DR = 0: t-test, systemic injection: P = 0.3; intracerebral infusion: P = 0.4).

As previously reported work (Warburton et al. 2003; Winters et al. 2006) had not looked at the effects of muscarinic antagonism at both 20-min and 24-h delays under the same experimental conditions, to allow direct comparison with the effects of MLA, Experiment 2 sought the effects of the broad spectrum muscarinic antagonist scopolamine under the same experimental conditions as for MLA.

Experiment 2: Object recognition memory following administration of the muscarinic receptor antagonist scopolamine

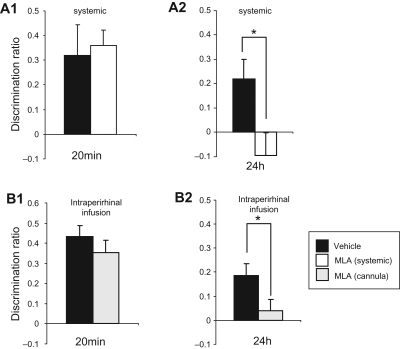

Figure 3 reveals that scopolamine impaired recognition memory at a delay of 20 min, but not at a delay of 24 h, whether administration was systemic (0.05 mg/kg) or local via cannula infusion (0.05 ng/μL) into the perirhinal cortex.

Figure 3.

Effect of scopolamine on object recognition memory at 20 min and 24 h tested in Dark Agouti rats in the arena. (A) Effect of systemic injection of scopolamine (0.05 mg/kg, ip) prior to object recognition memory testing. Scopolamine impaired memory at a 20 min (A1) but not at a 24 h (A2) delay. (B) Effect of intraperirhinal infusion of scopolamine (0.05 ng/µL) prior to object recognition memory testing. Scopolamine impaired memory at a 20-min (B1) but not at a 24-h (B2) delay. (*) Significance of ANOVA test at P < 0.05.

Analyzing across all ofthe scopolamine conditions, three factor ANOVA (delay [20 min or 24 h], administration route [systemic injection or intracerebral infusion], treatment [vehicle or drug]) revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(1,39) = 13.67, P = 0.001) and a significant interaction of treatment by delay (F(1,39) = 10.27, P = 0.003). Data for the two delays were therefore analyzed separately.

For the 20-min delay tests, two factor ANOVA (administration route, treatment) showed a significant effect of treatment (F(1,20) = 15.49, P = 0.001) and no significant interaction of administration route by treatment (F(1,20) < 1, P = 0.7). The scopolamine-treated animals did not show significant discrimination in the test (DR > 0: t-test, intracerebral infusion: P = 0.5, systemic injection: P = 0.5).

For the 24-h delay tests, two factor ANOVA (administration route, treatment) showed no significant effect of treatment (F(1,19) < 1, P = 0.6) and no significant interaction of administration route by treatment (F(1,19) = 1.19, P = 0.3). The scopolamine-treated animals showed significant discrimination in the test (DR > 0: t-test, intracerebral infusion: P = 0.001, systemic injection: P = 0.001).

The deficit at 20 min for scopolamine replicated the findings of Warburton et al. (2003). However, the failure to find a clear impairment with scopolamine at a 24-h delay conflicts with the findings of Winters et al. (2006). Winters et al. (2006) investigated the effects of scopolamine using a Y-maze and Lister Hooded rats. In studies reported in the Supplementary Material (Experiments 1SA,B; Figs. 1SA,B), the same pattern of memory loss, with impairment at 20 min, but unimpaired performance at 24 h, was found using a Y-maze or using Lister Hooded rats, thereby confirming the findings of Experiment 2. As the pattern of scopolamine-induced impairment was unusual, Experiment 3 tested broad-spectrum muscarinic antagonism produced by a different compound, AFDX-384.

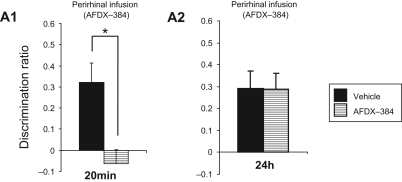

Experiment 3: Object recognition memory following intraperirhinal infusion of the muscarinic receptor antagonist AFDX-384

To determine whether the unusual pattern of impairment produced by scopolamine was replicable with a different muscarinic antagonist, experiments were undertaken using the AFDX-384 at a dose sufficiently high to antagonize all muscarinic receptor subtypes (Dorje et al. 1991). Administration was by local perirhinal infusion (12 ng/µL), and Dark Agouti rats were tested in the arena.

Figure 4 reveals that AFDX-384 produced the same pattern of memory deficit as scopolamine: impairment at 20 min, but not 24 h. An overall analysis by two factor ANOVA (delay [20 min or 24 h], treatment [vehicle or drug]) revealed a near-significant effect of treatment (F(1,15) = 4.35, P = 0.06) and a near-significant interaction of treatment by delay (F(1,15) = 4.16, P = 0.06). To allow closer comparison with the findings for scopolamine, data for the two delays were analyzed separately.

Figure 4.

Effect of the muscarinic antagonist AFDX-384 on recognition memory at 20-min and 24-h delays tested in Dark Agouti rats in the arena. Intraperirhinal infusion of AFDX-384 (12 ng/µL) to object recognition memory prior to object recognition memory testing impaired memory after a 20-min (A1), but not a 24-h (A2) delay.

For the 20-min delay, the post hoc analysis showed significant impairment for the muscarinic antagonist-treated animals compared with controls (ANOVA: F(1,8) = 7.64, P = 0.02); the AFDX-384-treated animals did not show significant discrimination (DR = 0: t-test: P = 0.4).

For the 24-h delay, the post hoc analysis showed no significant impairment for the muscarinic antagonist-treated animals compared with controls (ANOVA: F(1,7) = <1, P > 0.9); the AFDX-384-treated animals showed significant discrimination (DR > 0: t-test, AFDX-384: P = 0.006).

To further investigate the unusual pattern of impairment produced by scopolamine and AFDX-384, the experiment was repeated with the selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist pirenzepine. Pirenzepine produced the same pattern of memory deficit as scopolamine and AFDX-384: impairment at a 20-min, but not a 24-h delay (see Supplemental Material).

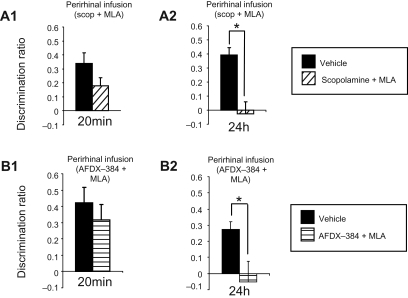

Given the different impairments found with nicotinic and muscarinic antagonism, it was predicted that coadministration of both types of antagonist should produce an impairment at both long and short delays: this was tested in Experiment 4.

Experiment 4: Object recognition memory following combined intraperirhinal infusion of MLA and a muscarinic antagonist

To test the expectation of impairment at both delays, MLA was coinfused with scopolamine or AFDX-384 at the doses previously used. Figure 5 shows the results after Dark Agouti rats were tested in the square arena.

Figure 5.

Effect of coinfusion of muscarinic antagonists and MLA on object recognition memory at 20-min or 24-h delays in Dark Agouti rats tested in the arena. (A) Effect of intraperirhinal infusion of scopolamine with MLA prior to object recognition memory testing. Scopolamine with MLA did not impair memory at a 20-min (A1), but did at a 24-h (A2) delay. (B) Effect of intraperirhinal infusion of AFDX-384 with MLA prior to object recognition memory testing. AFDX-384 with MLA did not impair memory at a 20-min (B1), but did at a 24-h (B2) delay. (*) P < 0.05.

Analyzing across all of the conditions, three factor ANOVA (delay [20 min or 24 h], drug combination [MLA + scop, MLA + AFDX-384], treatment [vehicle or drug]) revealed a significant effect of treatment (F(1,35) = 18.81, P < 0.001) and a significant interaction of treatment by delay (F(1,35) = 4.02, P = 0.05). For the 20-min delay test, two factor ANOVA (drug combination [MLA + scop, MLA + AFDX-384], treatment [vehicle or drug]) showed no significant effect of treatment (F(1,17) = 2.69, P = 0.12) and no significant interaction of treatment by drug combination (F(1,17) = <1, P = 0.7). For the 24-h delay test, two factor ANOVA (drug combination [MLA + scop, MLA + AFDX-384, MLA + pirenzepine], treatment [vehicle or drug]) showed a significant effect of treatment (F(1,18) = 20.37, P < 0.001) and no significant interaction of treatment by drug combination (F(1,18) < 1, P = 0.7). Hence, in each case the pattern of impairment mirrored that produced by MLA with impairment only at the 24-h delay rather than there being an impairment at both delays.

The results for the individual drug coadministrations are as follows. At the 20-min delay there was no significant effect of treatment (all Ps > 0.1) for MLA plus scopolamine or MLA plus AFDX-38. In each case the drug group showed significant discrimination (DR > 0; P > 0.01). At the 24-h delay there was a significant effect of treatment for MLA plus scopolamine (ANOVA, F(1,11) = 12.93, P = 0.004), and MLA plus AFDX-38 (ANOVA, F(1,7) = 9.82, P = 0.02). In both cases the drug group failed to show significant discrimination (DR > 0; P > 0.2).

Taken together, the results for coapplication of MLA and muscarinic antagonists (scopolamine or AFDX-384) provide evidence against an additive effect for antagonism of nicotinic receptors and muscarinic receptors. Coinfusions of MLA and scopolamine, or MLA and AFDX-384 all blocked memory after a 24-h but not a 20-min delay. Hence, addition of the muscarinic antagonist did not alter the profile of impairment produced by MLA administered alone, so that MLA appeared to override the effect of muscarinic antagonism.

Discussion

The results demonstrate a double dissociation in the effects of nicotinic and muscarinic receptor antagonism on object recognition memory measured at 20-min and 24-h delays. Nicotinic antagonism does not impair memory measured after 20 min, but does impair memory after 24 h, whereas blockade of muscarinic receptors impairs memory after 20 min, but not after 24 h. Coapplication of the nicotinic antagonist MLA and a muscarinic antagonist resulted in impairment at a delay of 24 h, but not at 20 min.

Effect of nicotinic antagonism on object recognition memory

The results demonstrate that when given so as to be active during acquisition, MLA impairs object recognition memory after 24 h, but not after 20 min. MLA has a well-documented action antagonizing neuronal α-bungarotoxin binding sites (Ward et al. 1990), which are known to reside primarily on α7 receptors (Davies et al. 1999; Whiteaker et al. 1999). However, there is evidence that MLA may also act at α3β2 and α4β2 nicotinic binding sites (Mogg et al. 2002). Accordingly, contributions to the effects produced by MLA on recognition memory by actions at α4β2 containing nicotinic receptors cannot be excluded. Effects from action at the α3β2 site are less likely, as α3β2 subunits are not among the main nicotinic receptor subunits in rodent cortex (Gotti et al. 2006). The profile of long-term (24-h) but not shorter-term (20-min) memory impairment produced by MLA is the same as that found with NMDA receptor antagonism (Barker et al. 2006b), metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonism (Barker et al. 2006a), L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blockade (Seoane et al. 2009), and calcium calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CAMKII) antagonism with KN-62 or autocamtide-2 related inhibitory peptide (AIP) (Tinsley et al. 2009). A previous study (Pichat et al. 2007) found no effect of MLA on object recognition memory at a 1-h delay, though MLA administered intracerebroventricularly in rats has been reported to impair social recognition memory at a 15-min delay (Van Kampen et al. 2004). Further, the α7 receptor agonist, N-[(3R)-1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-3-yl]-7-[2-(methoxy)phenyl]-1-benzofuran-2-carboxamide (ABBF), enhances social recognition memory after a 24-h delay, this enhancement being blocked by MLA (Boess et al. 2007). As the effects of infusing MLA after acquisition were not tested in the present study, it is possible that the memory deficit at a 24-h delay is due to consolidation rather than acquisition mechanisms. Scopolamine given after acquisition or so as to be active during retrieval does not produce an impairment in object recognition memory at a 20-min delay (Warburton et al. 2003); hence, this memory impairment can be ascribed to antagonism of muscarinic receptors during acquisition, rather than actions on retrieval or consolidation mechanisms.

Effect of muscarinic antagonism on object recognition memory

Muscarinic antagonism impaired object recognition memory after a 20-min delay, but not after a 24-h delay. This same unusual pattern of impairment was found for scopolamine, AFDX-384, and pirenzepine. Pirenzepine produced a parallel pattern of impairment to scopolamine (see Supplemental Material), suggesting that the dependency of the deficit is dependent upon M1 rather than other subtypes of muscarinic receptors. The same pattern of deficit was found for both systemic and local perirhinal infusions of scopolamine, in both Dark Agouti and Lister Hooded rat strains (see Supplemental Material). Such a counterintuitive pattern of impairment with amnesia being followed by remembrance has also been described when perirhinal kainate receptors are antagonized (Barker et al. 2006b). AFDX-384 given systemically (1 mg/kg—lower than the dose used in the current experiments) has previously been reported to have no effect on object recognition memory with a 1-h delay (Vannucchi et al. 1997). Impairments of object recognition memory by scopolamine have been reported for delays of 20 min (Warburton et al. 2003), 1 h (Vannucchi et al. 1997), 3 h (Dodart et al. 1997), and 24 h (Winters et al. 2006). In unpublished experiments in Bristol (Fontaine-Palmer 2008) scopolamine was found to impair object recognition memory after a delay of 1 h (in agreement with Vannucchi et al. 1997) or 3 h (Dodart et al. 1997), but not after a delay of 6 h. We have found no reports of the effects of scopolamine on recognition memory at long (>3 h) delays in either monkeys or humans, but there are reports of impairment in monkeys at short delays (Aigner et al. 1991; Tang et al. 1997; Turchi et al. 2008; but, see Browning et al. 2010).

The lack of impairment found here for muscarinic antagonism at the 24-h delay contrasts with the previously reported scopolamine-induced impairment at that delay (Winters et al. 2006). However, in that study (Winters et al. 2006), the scopolamine-induced impairment was partial and the scopolamine-treated animals' discrimination was similar to that of other control groups in the study, albeit lower than that of its particular matched control group. There are several procedural differences between the two studies, including rat strain, testing arena shape, and precise details of cannulae implantation. Neither rat strain nor testing arena shape appear able to explain the pattern of impairment: In the present experiments, using systemic administration, no impairment for a 24-h delay was found for Dark Agouti rats in a square arena or in a Y-maze such as used by Winters et al. (2006) and neither was impairment found for Lister Hooded rats, such as used by Winters et al. (2006), when tested in a square arena (see Supplemental Material). The angle of approach of infusion cannulae differs in the two studies, though coordinates within perirhinal cortex appear to overlap: Winters and colleagues used a vertical approach, whereas our cannulae were angled at 20° to the vertical; however, if used as a basis for explanation, there would then be generated a discrepancy between the results for systemic and intracerebral administration routes. The dose of scopolamine (0.05 ng/µL; 130 nM) in the present experiments was lower than that (10 µg/µL; 26 mM) used by Winters et al. (2006) or Warburton et al. (2003). The lower dose was chosen so as to be closer to the reported Ki values (∼0.3–2 nM) (Huang et al. 2001) for scopolamine and thereby avoid any significant increase in osmolarity and possible nonselective effects. Nevertheless, experiments performed with infusion of 10 µg/µL of scopolamine (data not included), as used in previous reports, produced the same pattern of results as the lower dose (significant impairment at 20 min, and no impairment at 24 h).

The effect of coinfusing α7 nicotinic and muscarinic antagonists on object recognition memory

In the current experiments, when muscarinic antagonists were coapplied with the nicotinic receptor antagonist MLA, memory was blocked after a 24-h delay, but memory after a 20-min delay was unimpaired. In each instance, the dose of the muscarinic antagonist given alone was sufficient to produce amnesia at the shorter (20-min) delay. Hence, unexpectedly, for memory after a 20-min delay, addition of a potentially amnesic dose of a muscarinic antagonist to a potentially amnesic dose of a nicotinic antagonist removed the impairment produced by the single dose of the muscarinic antagonist. Accordingly, the effects of giving a muscarinic and an α7 nicotinic antagonist together were not additive: The anticipated memory impairment at both 20 min and 24 h was not seen. Titrating dosages of antagonists against each other was not an objective of the current experiments, so it remains to be discovered whether there are doses of a nicotinic plus a muscarinic antagonist that would result in impairment at both 20-min and 24-h delays. (However, coinfusion of MLA with a very high dose of scopolamine [10 µg/µL] left an impairment at the 20-min delay, but did not produce impairment at the 24-h delay [data not included].) These findings were unexpected and provide a challenge to simple ideas about the action of cholinergic receptors in recognition memory: Clearly, the effects of muscarinic and nicotinic antagonism are neither independent nor additive. We have not found reports that scopolamine has agonistic/antagonistic effects on nicotine receptors or that MLA has effects on muscarinic receptors. However, there are multiple opportunities for interactions involving the two types of antagonism, for example, involving presynaptic autoreceptors or alterations in the balance of excitation and inhibition in local circuits. Indeed, there is evidence of interactions involving the two types of receptors: The muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine can either inhibit or potentiate the responses of nicotinic receptors (Zwart and Vijverberg 1997; Parker et al. 2003; Gonzalez-Rubio et al. 2006). Moreover, an interaction between an α7 agonist and scopolamine has been reported previously: The α7 agonist AR-R 17779 reverses the scopolamine-induced impairment in social recognition memory seen at a 15-min delay in rats (Van Kampen et al. 2004). Additionally, AFDX-384 has been reported to reverse the scopolamine-induced impairment of recognition memory at a delay of 1 h (Vannucchi et al. 1997), so that interactions amongst cholinergic receptor subtypes are potentially complex. Eventual explanation of the effects of coadministration found in the current experiments is likely to depend on an understanding of the balance of excitation and inhibition produced by specific cholinergic receptor activations in local perirhinal networks.

The different temporal patterns of impairment produced by antagonism of muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptors in perirhinal cortex mirror those previously described for kainate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonism (Barker et al. 2006b). A potential explanation for these results is provided by following the argument given by Barker et al. (2006b): They suggested that muscarinic (as well as kainate) receptor activation is necessary for the plastic processes of fast-changing perirhinal neuronal responses (“novelty” and “recency” responses) (Xiang and Brown 1998) that are hypothesized to support shorter-term (20-min delay) memory, while nicotinic (as well as NMDA) receptor activation is necessary for the plastic processes of slow-changing perirhinal neuronal responses (“familiarity” responses) (Xiang and Brown 1998) that are hypothesized to support long-term (24-h delay) memory. Muscarinic receptors have been shown to be involved in perirhinal plastic processes (Massey et al. 2001; Warburton et al. 2003), but the involvement of nicotinic receptors in such perirhinal processes is unknown. Studies of processes in other memory systems have reported that certain neurons (Blum et al. 2009), receptors (McNamara et al. 2008), or intracellular pathways (Izquierdo et al. 2000b) support distinct mechanisms for shorter- and longer-term memory.

In sum, our results indicate that (1) shorter- and longer-term object recognition memory are dependent upon different cholinergic receptor types, and (2) that the effects of antagonism of the two types of receptor within the perirhinal cortex are neither independent nor additive. The findings present a challenge to simple ideas about cholinergic actions in recognition memory.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Forty-seven male Dark Agouti rats (200–230 g; Bantin and Kingman, Hull, UK) were used for object recognition experiments. All of the animals were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle (light phase, 18.00–06.00 h). Experiments were conducted during the dark phase of the cycle. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals Scientific Procedures Act (1986) and University of Bristol Ethical Review Group.

Object recognition following administration of cholinergic antagonists

Surgery

Prior to testing in the novel object preference test (NOP) test, 25 rats underwent surgical procedures to implant guide cannulae into the perirhinal cortex. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (Merial, Harlow, UK) and placed in a stereotaxic frame with the incisor bar set so as to achieve a horizontal skull. Craniotomies were made 5.6-mm posterior and 4.5-mm lateral to bregma, and 10-mm length, 26-gauge stainless-steel guide cannulae (Plastics One) were inserted 6.7 mm below the surface of the skull in the coronal plane at an angle of 20° to the vertical. The cannulae were attached to the surface of the skull by constructing an implant made from bone cement (DePuy, UK) and attached to the skull with stainless-steel screws (Plastics One). After surgery, rats were allowed a 2-wk recovery period, during which they were housed singly. Post-recovery, cannulated rats were housed in pairs in large cages. Obdurators (Plastics One) were used to keep the cannulae patent between infusions.

Novel object preference test (NOP) test

In a pretraining period, rats were habituated to an arena (length: 100 cm, depth: 100 cm, arena height: 40 cm) surrounded by curtains, (height from arena base: 40–160 cm) in one 5-min period each day for 4 d. For the novel object preference test (NOP) test, rats underwent an acquisition trial and choice trial separated by a delay (20 min or 24 h). During the acquisition trial, each rat was initially exposed to two identical copies of an object (Object A) until it had explored the objects for >40 sec or had spent a maximum of 4 min in the arena. Objects were constructed from Duplo (Lego UK, Slough, UK) (length: ∼16 cm, depth: ∼16 cm, height: ∼12 cm). After a delay period of 20 min or 24 h, each rat was exposed to another copy of Object A and a novel object (Object B) in a choice trial lasting 3 min. In one preferential object recognition memory experiment rats were placed in a Y-maze with the objects positioned in two of the arms (see Supplemental Material; Winters et al. 2006).

Infusions and intraperitoneal injections

Drugs

In each experiment, drug administration was either by a systemic injection or by bilateral intracerebral infusion via guide cannulae directed at the perirhinal cortex. Systemic administration was via an intraperitoneal injection at a volume of 1 mL/kg given 30 min prior to the acquisition trial. Rats received bilateral infusions into the perirhinal cortex using 33-gauge infusion cannula (Plastics One) inserted into the implanted guide cannula and attached to a 25-µL Hamilton syringe by polyethylene tubing. An infusion pump (Harvard Bioscience) was used to inject a volume of 1 µL to each hemisphere during a 2-min period. Infusion cannulae were kept in place for a further 5 min following the infusion. Intracerebral drug infusions were given 15 min prior to acquisition trial, thereby allowing time for the systemic injections to be effective, as in previous studies (Warburton et al. 2003; Winters et al. 2006). The receptor antagonists used were methyllylcaconitine (MLA), scopolamine hydrobromide, AFDX-384, and pirenzepine, all supplied by Tocris Biosciences (Bristol, UK). Previous work with intracerebral infusions indicates that drugs may persist at effective concentrations for ∼1 h post-infusion (Day et al. 2003).

Experiment 1

Dark Agouti rats were administered the nicotinic antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) either systemically at a dose of 87.5 µg/kg or via an intracerebral injection of 0.0875 ng/µL (infusate = 100 nM).

Experiment 2

A: Dark Agouti rats were administered the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine hydrobromide systemically at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg (arena). B: Dark Agouti rats were administered scopolamine hydrobromide via an intracerebral infusion (0.05 ng/μL) (arena) (infusate = 130 nM).

Experiment 3

Dark Agouti rats were administered the nonselective muscarinic antagonist AFDX-384 at a dose of 12 ng/µL (infusate = 25 µM) intracerebrally.

Experiment 4

A: Dark Agouti rats were administered both MLA and 0.05 ng/µL of scopolamine. B: Dark Agouti rats were administered both MLA (0.0875 ng/µL) and AFDX-384 (12 ng/µL) intracerebrally. In each part of Experiment 4, both compounds were dissolved in the same saline solution and infused into the perirhinal cortex as described above.

The dose for MLA was selected so as not to produce deficits in locomotion (Chilton et al. 2004). A high dose of AFDX-384 was required with the aim of blocking all muscarinic subtypes, as occurs with scopolamine (Dorje et al. 1991; Collison et al. 2000). Concentrations of infusate (or systemic doses) were chosen to be 50–100 times that of the designated Ki value for the target receptor to ensure maximal inhibition, but limit nonselective effects. Ki values previously reported for the compounds used are MLA(α7): ∼1 nM (Ivy Carroll et al. 2007), scopolamine (M1–M5): ∼0.3–2 nM (Huang et al. 2001), and AFDX-384 (M1–M5): ∼6 nM–530 nM (Dorje et al. 1991). Half-lives for the drugs used were: MLA = 18 min (Stegelmeier et al. 2003), scopolamine = 3.7 h (Ebert et al. 1998), and AFDX-384 = 40 min (Mickala et al. 1996).

Each experiment was run in two parts in a cross-over design. In the first part, rats were randomly assigned an infusion/injection of drug or vehicle (0.9% saline for MLA, scopolamine; 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in 0.9% saline for the AFDX-384) and an object recognition experiment was performed. In the second part, each rat was given the opposite infusate/injectate and a second object recognition experiment was performed using new objects. There was a minimum separation of 48 h between the two parts of the experiment.

Data analysis

The time spent exploring each object was scored using a computer program with the experimenter blind to the treatment. Exploratory behavior was defined as the rat directing its nose toward the object at a distance of <2 cm; other behavior, such as looking around while sitting on the object, was not considered exploration. A discrimination ratio (DR) was used to measure memory and was calculated by dividing the difference in time exploring the novel and the familiar object by the time taken exploring both objects. Rats that failed to complete a minimum of a 10-sec exploration in the acquisition phase or a minimum of 5 sec for the choice trial, were excluded from the analysis. Over the course of the experiments, occasionally rats had to be excluded from the analysis due to cannula failures.

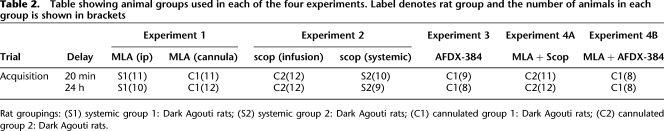

Table 2 includes a summary of the rat groups included in the statistical analysis of the drug experiments. Where rats were used in more than one experiment, the experiments were performed in the following order. Group C1: (1) MLA, 20 min, (2) MLA, 24 h, (3) AFDX-384, 20 min, (4) AFDX-384, 24 h, (5) AFDX-384 & MLA, 20 min, and (6) AFDX-384 & MLA, 24 h. Group C2: (1) scopolamine, 20 min, (2) scopolamine and MLA, 24 h, and (3) scopolamine, 24 h. Discrimination ratios were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with factors treatment (drug/vehicle) and infusion time. The significance level was P = 0.05, two-tailed.

Table 2.

Table showing animal groups used in each of the four experiments. Label denotes rat group and the number of animals in each group is shown in brackets

Rat groupings: (S1) systemic group 1: Dark Agouti rats; (S2) systemic group 2: Dark Agouti rats; (C1) cannulated group 1: Dark Agouti rats; (C2) cannulated group 2: Dark Agouti rats.

Verification of cannulae positions

Rats were anesthetized with Euthatal (Rhône Mérieux, Toulouse, France) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing formal saline, pH7.4. Coronal sections (40 µm) were cut on a freezing microtome and the sections were stained with cresyl violet. Cannula locations were compared with a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Watson 1998), and histological examination confirmed that the tips of the cannulae were within the perirhinal cortex (Shi and Cassell 1999), see Figure 1A. Our cannula-tip locations matched the caudal region of the perirhinal cortex (−5.8 with respect to bregma) known to correlate with object recognition memory deficits (Albasser et al. 2009). Data from other laboratories (Martin 1991; Izquierdo et al. 2000a; Attwell et al. 2001) and our data (Seoane et al. 2011) indicate that the infused tissue extended to an ∼0.5–1 mm radius of the cannula tip. This volume includes the majority of perirhinal cortex (Shi and Cassell 1999), but only minor parts of neighboring entorhinal cortex or area Te2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MRC, Wellcome Trust, and a BBSRC studentship to N.S.F.-P. We thank Jane Robbins for technical assistance.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

References

- Abe H, Iwasaki T 2001. NMDA and muscarinic blockade in the perirhinal cortex impairs object discrimination in rats. Neuroreport 12: 3375–3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW 2006. Interleaving brain systems for episodic and recognition memory. Trends Cogn Sci 10: 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Albasser MM, Aggleton DJ, Poirier GL, Pearce JM 2010. Lesions of the rat perirhinal cortex spare the acquisition of a complex configural visual discrimination yet impair object recognition. Behav Neurosci 124: 55–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigner TG, Walker DL, Mishkin MM 1991. Comparison of the effects of scopolamine administered before and after acquisition in a test of visual recognition memory in monkeys. Behav Neural Biol 55: 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albasser MM, Davies M, Futter JE, Aggleton JP 2009. Magnitude of the object recognition deficit associated with perirhinal cortex damage in rats: Effects of varying the lesion extent and the duration of the sample period. Behav Neurosci 123: 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell PJ, Rahman S, Yeo CH 2001. Acquisition of eyeblink conditioning is critically dependent on normal function in cerebellar cortical lobule HVI. J Neurosci 21: 5715–5722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Bashir ZI, Brown MW, Warburton EC 2006a. A temporally distinct role for group I and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in object recognition memory. Learn Mem 13: 178–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Warburton EC, Koder T, Dolman NP, More JC, Aggleton JP, Bashir ZI, Auberson YP, Jane DE, Brown MW 2006b. The different effects on recognition memory of perirhinal kainate and NMDA glutamate receptor antagonism: Implications for underlying plasticity mechanisms. J Neurosci 26: 3561–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini L, Casamenti F, Pepeu G 1996. Aniracetam restores object recognition impaired by age, scopolamine, and nucleus basalis lesions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 53: 277–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besheer J, Short KR, Bevins RA 2001. Dopaminergic and cholinergic antagonism in a novel-object detection task with rats. Behav Brain Res 126: 211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner RS, Bunnelle WH, Anderson DJ, Briggs CA, Buccafusco J, Curzon P, Decker MW, Frost JM, Gronlien JH, Gubbins E, et al. 2007. Broad-spectrum efficacy across cognitive domains by α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonism correlates with activation of ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation pathways. J Neurosci 27: 10578–10587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum AL, Wanhe LI, Cressy M, Dubnau J 2009. Short and Long-term memory in Drosophila require cAMP signaling in distinct neuron types. Curr Biol 19: 1341–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boess FG, De Vry J, Erb C, Flessner T, Hendrix M, Luithle J, Methfessel C, Riedl B, Schnizler K, van der Staay FJ, et al. 2007. The novel α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist N-[(3R)-1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-3-yl]-7-[2-(methoxy)phenyl]-1-benzofuran-2- carboxamide improves working and recognition memory in rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 716–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Aggleton JP 2001. Recognition memory: What are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Warburton EC, Aggleton JP 2010. Recognition memory: Material, processes and substrates. Hippocampus 20: 1228–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning PG, Gaffan D, Croxson PL, Baxter MG 2010. Severe scene learning impairment, but intact recognition memory, after cholinergic depletion of inferotemporal cortex followed by fornix transection. Cereb Cortex 20: 282–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yamada K, Nabeshima T, Sokabe M 2006. α7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor as a target to rescue deficit in hippocampal LTP induction in beta-amyloid infused rats. Neuropharmacology 50: 254–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton M, Mastropaolo J, Rosse RB, Bellack AS, Deutsch SI 2004. Behavioral consequences of methyllycaconitine in mice: A model of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor deficiency. Life Sci 74: 3133–3139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collison DJ, Coleman RA, James RS, Carey J, Duncan G 2000. Characterization of muscarinic receptors in human lens cells by pharmacologic and molecular techniques. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41: 2633–2641 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D 2007. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47: 699–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AR, Hardick DJ, Blagborough IS, Potter BV, Wolstenholme AJ, Wonnacott S 1999. Characterisation of the binding of [3H]methyllycaconitine: A new radioligand for labelling α 7-type neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 38: 679–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Langston R, Morris RG 2003. Glutamate-receptor-mediated encoding and retrieval of paired-associate learning. Nature 424: 205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodart JC, Mathis C, Ungerer A 1997. Scopolamine-induced deficits in a two-trial object recognition task in mice. Neuroreport 8: 1173–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorje F, Wess J, Lambrecht G, Tacke R, Mutschler E, Brann MR 1991. Antagonist binding profiles of five cloned human muscarinic receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 256: 727–733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton A, Parker A 2003. A cholinergic explanation of dense amnesia. Cortex 39: 813–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert U, Siepmann M, Oertel R, Wesness KA, Kirch W 1998. Pharmacokinetics and phramacodynamics of scopolamine after subcutaneous administration. J Clin Pharmacol 38: 720–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Meliani K 1992. Effects of physostigmine and scopolamine on rats' performances in object-recognition and radial-maze tests. Psychopharmacology 109: 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Neave N, Aggleton JP 1996. Neurotoxic lesions of the perirhinal cortex do not mimic the behavioural effects of fornix transection in the rat. Behav Brain Res 80: 9–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine-Palmer N 2008. The role of muscarinic receptors and intracellular signalling pathways in visual recognition memory. PhD thesis Bristol University, Bristol, UK [Google Scholar]

- Freir DB, Herron CE 2003. Nicotine enhances the depressive actions in the rat hippocampal CA1 Region in vivo. J Neurophysiol 89: 2917–2922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffan D, Murray EA 1992. Monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) with rhinal cortex ablations succeed in object discrimination learning despite 24-hr intertrial intervals and fail at matching to sample despite double sample presentations. Behav Neurosci 106: 30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rubio JM, Garcia de Diego AM, Egea J, Olivares R, Rojo J, Gandia L, Garcia AG, Hernandez-Guijo JM 2006. Blockade of nicotinic receptors of bovine adrenal chromaffin cells by nanomolar concentrations of atropine. Eur J Pharmacol 535: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F 2006. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Native subtypes and their relevance. TIPS 27: 482–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Giocomo LM 2006. Cholinergic modulation of cortical function. J Mol Neurosci 30: 133–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Stern CE 2006. Mechanisms underlying working memory for novel information. Trends Cogn Sci 10: 487–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Buchwald P, Browne CE, Farag HH, Wu WM, Ji G, Bodor N 2001. Receptor binding studies of soft anticholinergic agents. AAPS PharmSci 3: E30 10.1208/ps030430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston AE, Aggleton JP 1987. The effects of cholinergic drugs upon recognition memory in rats. Q J Exp Psychol 39: 297–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy Carroll F, Ma W, Navarro HA, Abraham P, Wolckenhauer SA, Damaj MI, Martin BR 2007. Synthesis, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor binding, antinociceptive and seizure properties of methyllycaconitine analogs. Bioorg Med Chem 15: 678–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo LA, Barros DM, Ardenghi PG, Pereira P, Rodrigues C, Choi H, Medina JH, Izquierdo I 2000a. Different hippocampal molecular requirements for short- and long-term retrieval of one-trial avoidance learning. Behav Brain Res 111: 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo LA, Vianna M, Barros DM, Sousa TM, Ardenghi P, Sant Anna MK, Rodrigues C, Medina JH, Izquierdo I 2000b. Short- and Long-Term memory are differentially affected by metabolic inhibitors given into hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Neurobiol Learn Mem 73: 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH 1991. Autoradiographic estimation of the extent of reversible inactivation produced by microinjection of lidocaine and muscimol in the rat. Neurosci Lett 127: 160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Bhabra G, Cho K, Brown MW, Bashir ZI 2001. Activation of muscarinic receptors induces protein synthesis-dependent long-lasting depression in the perirhinal cortex. Eur J Neurosci 14: 145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Matsumoto A, Enomoto T, Nishizaki T 2000. Activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors induces long-term potentiation in vivo in the intact mouse dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci 12: 3741–3747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara AM, Magidson PD, Linster C, Wilson DA, Cleland TA 2008. Distinct neurla mechanisms mediate olfactory memory formation at different timescales. Learn Mem 15: 117–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Mishkin M, Murray EA 1993. Effects on visual recognition of combined and separate ablations of the entorhinal and perirhinal cortex in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci 13: 5418–5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Hadfield W, Bachevalier J, Murray EA 1996. Effects of rhinal cortex lesions combined with hippocampectomy on visual recognition memory in rhesus monkeys. J Neurophysiol 75: 1190–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickala P, Boutin H, Bellanger C, Chevalier C, MacKenzie ET, Dauphin F 1996. In vivo binding pharmacokinetics and metabolism of the selective muscarinic antagonists [3H]AF-DX 116 and [3H]AF-DX 384 in the anesthetized rat. Nucl Med Biol 23: 173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg AJ, Whiteaker P, McIntosh M, Marks M, Collins AC, Wonnacott S 2002. Methyllycaconitine is a potent antagonist of α-Conotoxin-MII-sensitive presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat striatum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG 2001. Perspectives on object-recognition memory following hippocampal damage: Lessons from studies in rats. Behav Brain Res 127: 159–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG, Pinel JP 1994. Rhinal cortex lesions and object recognition in rats. Behav Neurosci 108: 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG, Piterkin P, Lecluse V, Lehmann H 2007. Perirhinal cortex damage and anterograde object-recognition in rats after long retention intervals. Behav Brain Res 185: 82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Bussey TJ 1999. Perceptual-mnemonic functions of the perirhinal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 3: 142–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman G, Brooks SP, Hennebry GM, Eacott MJ, Little HJ 2002. Nimodipine prevents scopolamine-induced impairments in object recognition. J Psychopharmacol 16: 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JC, Sarkar D, Quick MW, Lester RA 2003. Interactions of atropine with heterologously expressed and native α 3 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Br J Pharmacol 138: 801–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C 1998. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- Pichat P, Bergis OE, Terranova JP, Urani A, Duarte C, Santucci V, Gueudet C, Voltz C, Steinberg R, Stemmelin J, et al. 2007. SSR180711, a novel selective α7 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: (II) efficacy in experimental models predictive of activity against cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 32: 17–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem KS, Price JL, Hashikawa T 2007. Cytoarchitectonic and chemoarchitectonic subdivisions of the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 500: 973–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent PB 1993. The diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci 16: 403–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP 1997. Cognitive functions of cortical acetylcholine: Toward a unifying hypothesis. Brain Res 23: 28–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP, Givens B 2003. Attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: What does it mean for learning and memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem 80: 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW 1993. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain α 7: A nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J Neurosci 13: 596–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane A, Massey PV, Keen H, Bashir ZI, Brown MW 2009. L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel antagonists impair perirhinal long-term recognition memory and plasticity processes. J Neurosci 29: 9534–9544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane A, Tinsley CJ, Brown MW 2011. Interfering with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression impairs recognition memory in rats. Hippocampus 21: 121–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi CJ, Cassell MD 1999. Perirhinal cortex projections to the amygdaloid complex and hippocampal formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol 406: 299–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegelmeier BL, Hall JO, Gardner DR, Panter KE 2003. The toxicity and kinetics of larkspur alkaloid, methyllycaconitine, in mice. J Anim Sci 81: 1237–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Mishkin M, Aigner TG 1997. Effects of muscarinic blockade in perirhinal cortex during visual recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 12667–12669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley CJ, Narduzzo KE, Ho JW, Barker GR, Brown MW, Warburton EC 2009. A role for calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the consolidation of visual object recognition memory. Eur J Neurosci 30: 1128–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchi J, Buffalari D, Mishkin M 2008. Double dissociation of pharmacologically induced deficits in visual recognition and visual discrimination learning. Learn Mem 15: 565–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kampen M, Selbach K, Schneider R, Schiegel E, Boess F, Schreiber R 2004. AR-R 17779 improves social recognition in rats by activation of nicotinic α7 receptors. Psychopharmacology 172: 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi MG, Scali C, Kopf SR, Pepeu G, Casamenti F 1997. Selective muscarinic antagonists differentially affect in vivo acetylcholine release and memory performances of young and aged rats. Neuroscience 79: 837–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytko ML 1996. Cognitive functions of the basal forebrain cholinergic system in monkeys: Memory or attention? Behav Brain Res 75: 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Koder T, Cho K, Massey PV, Duguid G, Barker GR, Aggleton JP, Bashir ZI, Brown MW 2003. Cholinergic neurotransmission is essential for perirhinal cortical plasticity and recognition memory. Neuron 38: 987–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Cockcroft VB, Lunt GG, Smillie FS, Wonnacott S 1990. Methyllycaconitine: A selective probe for neuronal α-bungarotoxin binding sites. FEBS Lett 270: 45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J 1993. Molecular basis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 14: 308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteaker P, Davies AR, Marks MJ, Blagbrough IS, Potter BV, Wolstenholme AJ, Collins AC, Wonnacott S 1999. An autoradiographic study of the distribution of binding sites for the novel α7-selective nicotinic radioligand [3H]-methyllycaconitine in the mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2689–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Bussey TJ 2005. Glutamate receptors in perirhinal cortex mediate encoding, retrieval, and consolidation of object recognition memory. J Neurosci 25: 4243–4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Forwood SE, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ 2004. Double dissociation between the effects of peri-postrhinal cortex and hippocampal lesions on tests of object recognition and spatial memory: Heterogeneity of function within the temporal lobe. J Neurosci 24: 5901–5908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ 2006. Paradoxical facilitation of object recognition memory after infusion of scopolamine into perirhinal cortex: Implications for cholinergic system function. J Neurosci 26: 9520–9529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Bartko SJ, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ 2007. Scopolamine infused into perirhinal cortex improves object recognition memory by blocking the acquisition of interfering object information. Learn Mem 14: 590–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ 2010. Implications of animal object memory research for human amnesia. Neuropsychologia 48: 2251–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang JZ, Brown MW 1998. Differential neuronal encoding of novelty, familiarity and recency in regions of the anterior temporal lobe. Neuropharmacology 37: 657–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zola-Morgan S, Squire LR, Amaral DG, Suzuki WA 1989. Lesions of perirhinal and parahippocampal cortex that spare the amygdala and hippocampal formation produce severe memory impairment. J Neurosci 9: 4355–4370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Vijverberg HP 1997. Potentiation and inhibition of neuronal nicotinic receptors by atropine: Competitive and noncompetitive effects. Mol Pharmacol 52: 886–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]