Abstract

Objectives

To systematically review and quantitatively synthesize the effect of vitamin D therapy on fall prevention in older adults.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting

MEDLINE, CINAHL,Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, LILACS, bibliographies of selected articles, and previous systematic reviews through February 2009 were searched for eligible studies.

Participants

Older adults (aged ≥60 years) who participated in randomized controlled trials that investigated the effectiveness of vitamin D therapy in the prevention of falls and used an explicit fall definition.

Measurements

Two authors independently extracted data including study characteristics, quality assessment, and outcomes. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity in a randomeffects model.

Results

Of 1,679 potentially relevant articles, 10 studies met inclusion criteria. In pooled analysis, vitamin D therapy (200-1000IU) reduced falls by 14% (relative risk [RR] 0.86;95% confidence interval 0.79-0.93;I2=7%) compared to calcium or placebo; number needed to treat=15. The following subgroups had significant fall reductions: community-dwelling (age<80 years), adjunctive calcium supplementation, no history of fractures/falls, duration>6 months, cholecalciferol, and dose≥800 IU. Meta-regression demonstrated no linear association of vitamin D dose or duration with treatment effect. Post-hoc analysis, including 7 additional studies (17 total) without explicit fall definitions, yielded smaller benefit (RR 0.92,0.87-0.98) and more heterogeneity (I2=36%) but found significant intergroup differences favoring adjunctive calcium versus none (p=0.001).

Conclusion

Vitamin D treatment effectively reduces the risk of falls in older adults. Future studies should investigate whether particular populations or treatment regimens may have greater benefit.

Keywords: Vitamin D, falls, elderly, randomized-controlled trials, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Falls are a common but serious cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults. Falls occur in up to 30% of community-dwelling adults, and up to 50% of institutionalized older adults, resulting in nearly 16,000 deaths in 2006.1-6 In addition to physical injury, falls can lead to a loss of independence and compromised emotional health.7 Falls are costly, accounting for $19 billion in health care expenditures in the year 2000.8,9 Thus, the implementation of an effective, inexpensive fall prevention strategy is highly desirable.

Falls result from a culmination of diverse risk factors acting in synergy with advancing age, disease states, and hazards in the environment. While there are a multitude of recognized risk factors, certain risk factors portend a particularly high risk for future falls, including abnormalities in muscle strength, gait, and balance.10,11 Recent studies have suggested that vitamin D supplementation is a safe, well-tolerated approach to improve muscle strength and function, leading to a decreased occurrence of falls12,13.

Older adults may be at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency for many reasons, including decreased cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D.14,15 Therefore, pharmacologic supplementation of vitamin D is often required in older adults. The most commonly available forms are native vitamin D (cholecalciferol or vitamin D3; ergocalciferol or vitamin D2; 25-hydroxyvitamin D), and active vitamin D (calcitriol, alfacalcidol or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).

Epidemiological studies support an association between vitamin D and falls.12 Vitamin D may reduce the risk of falls in older adults through an improvement in muscle function and strength.13 Muscle biopsies in vitamin D deficient patients demonstrate atrophy of type II fibers, which are recruited first to prevent a fall.16,17 Binding of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in muscle impacts transcription of genes which modulate calcium and phosphate uptake, phospholipid metabolism, and muscle cell proliferation and differentiation.16,17 In VDR knockout mice, impaired motor coordination is observed.16 Clinical vitamin D deficiency is associated with a proximal myopathy that improves with treatment.16,17 Body sway improves with vitamin D and calcium compared with calcium alone in elderly ambulatory women.18 Improvements in muscle strength, and subsequent gait stability, may explain the association of vitamin D therapy and fall prevention.

While previous reviews have either found insufficient evidence to conclude that vitamin D supplementation reduces the risk of falling,5, 21-23 or found greater benefit with active vitamin D,24-25 Bischoff-Ferrari and colleagues (2004)26 reported a significant 22% reduction in falls with any type of vitamin D. In a recent meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials by Bischoff-Ferrari et al. (2009),27 native vitamin D treatment reduced falls by 13% but with significant heterogeneity among studies. Only high dose vitamin D (700-1000 IU), achieved serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations >24ng/ml, and active vitamin D treatment significantly reduced fall risk by 19-23% in their review. Most previous meta-analyses were underpowered or did not examine specific subgroups of patients in whom vitamin D may have differential effects. In recent years, additional randomized controlled trials using various fall ascertainment techniques have been published reporting the potential benefits of vitamin D in the prevention of falls; therefore, an updated meta-analysis is warranted.

Our objective was to perform a comprehensive, updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials which evaluate the effectiveness of vitamin D therapy on fall prevention in older adults (mean age≥60 years). We add to recent findings from Bischoff-Ferrari et al. (2009)27 by investigating whether progressively higher doses of vitamin D are associated with greater benefits in fall risk. Further, we explore whether beneficial effects from vitamin D treatment extend to hospitalized patients and if particular patient factors (i.e. history of prior fracture or fall) and/or treatment regimens (i.e. adjunctive calcium use) contribute to the effect of vitamin D. We also undertake formal quality assessment of included studies to identify possible sources of systematic biases.

METHODS

Data Sources and Selection

We developed and followed a standardized protocol for all steps of the review. Investigators searched MEDLINE, CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, LILACS, and hand searched bibliographies of selected articles and previous systematic reviews to identify articles that potentially met our inclusion criteria. We used medical subject headings (i.e. MeSH), keywords, and truncated word vocabulary in our search strategies. The search strategy combined terms for the intervention of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D, ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol, calcitriol, hydroxycholecalciferols, dihydroxycholecalciferols, calcifediol, vitamin D2, vitamin D3, paricalcitol, vitamin D/analogs and derivatives), outcome of falls (accidental falls, body sway, gait) and study design of randomized clinical trials using the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (MEDLINE only)28. For smaller databases, the search strategy did not include syntax for study design in order to maximize the yield. All electronic databases were accessioned on February 9, 2009.

Study Selection

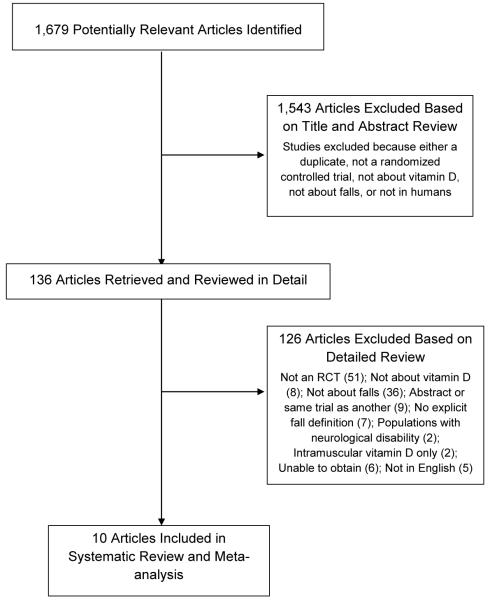

Two investigators independently reviewed the titles, abstracts or full-text manuscripts of relevant articles identified through the literature search to determine whether they met eligibility criteria (Figure 1). A study was eligible for inclusion if: 1) the study was a randomized, controlled trial; 2) the mean age of study participants was ≥60 years; 3) the study compared vitamin D treatment with either calcium therapy, placebo, or no treatment; 4) the number of participants with ≥1 fall by treatment arm was given; and 5) an explicit fall definition was provided along with a description of how falls were ascertained. Falls were defined as “unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor, or other lower level”.29 Studies that did not have an explicit fall definition were included in post-hoc analysis. We included all eligible studies regardless of dwelling (community, nursing institution, or hospital); participants’ history of fracture or fall; vitamin D levels; adjunctive calcium therapy; or dose, type, and duration of vitamin D therapy in order to examine potential subgroup effects. We excluded studies which only used intramuscular vitamin D since this route is not as effective.30 We also excluded studies restricted to participants with significant neurological disabilities, such as Parkinson’s disease or stroke with hemiplegia, where the independent effects of vitamin D on fall risk may be unclear. There were no restrictions on year or language, although at least one author had to be able to translate the study. Disagreements regarding inclusion and exclusion of studies were resolved by group consensus and by referring to the original reports.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart according to QUOROM guidelines.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Study investigators independently abstracted data in duplicate using a standardized form. The abstracted data was then entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) and verified by a second reviewer. Abstracted data included study design (i.e. date and location of study, sample size), patient characteristics (i.e. risk factors for falling, such as history of previous fracture or fall and comorbidities), study methodology (i.e. eligibility criteria, method of randomization, blinding), intervention (i.e. type, dose, duration of therapy), adverse events and main results. Disagreements were resolved by group consensus. Authors were not contacted directly for missing data. Methodological quality of included studies was investigated by collecting data on sources of systematic bias using published guidelines.31 Collected data included information regarding sequence generation, allocation concealment, assessor blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, eligibility criteria, therapies, excluded patients and reliability of fall ascertainment. Sources of funding were documented.

The primary outcome of the meta-analysis was the number of participants with ≥1 fall during follow-up. Studies where only the relative risk of falling in each treatment arm was reported, but not the number of fallers, were also included. We did not analyze the total number of falls since individuals with recurrent falls may have other significant risk factors for falling.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We calculated a summary relative risk (RR) for the primary (dichotomous) outcome of number of participants with ≥1 fall during follow-up. The planned analysis was vitamin D arm (with or without calcium) versus comparator arm (placebo, calcium, or no treatment). For studies that tested multiple doses of vitamin D in separate intervention arms, a pooled effect estimate from all arms with vitamin D were compared to a pooled effect estimate from all arms without vitamin D for our main analysis.

The presence of heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic for pooled study-level data. An I2 statistic of greater than 50% suggested moderate heterogeneity.32 Our a priori hypothesis was that there would be heterogeneity both between and within studies; thus, a random effects model was used. We conducted the following a priori subgroup analyses to explore potential heterogeneity between studies: 1) type, dose, and duration of vitamin D; 2) use of adjunctive calcium in treatment arm; 3) type of dwelling; 4) history of fall or fracture in majority of participants; and 5) mean baseline vitamin D level ≤30ng/ml (vitamin D insufficiency). Studies with arms that used multiple doses of vitamin D were each compared to the control arm to derive a relative risk of falling for the relevant subgroup analyses. We also performed a meta-regression analysis examining the linear association of dose and duration of vitamin D treatment with the relative risk of falling. Sensitivity analysis was performed on studies with similar baseline characteristics between intervention and control groups. Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s funnel plot and the Begg’s and Egger’s statistical tests.33,34 All analyses were performed using Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, Stata College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Search Results and Study Characteristics

A total of 1,679 unique titles and abstracts were retrieved from our search (Figure 1); 1,543 studies were excluded after title and abstract review because they did not satisfy our inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 136 articles underwent full text review, with 126 studies excluded (of these, 7 articles without an explicit fall definition were later examined in post-hoc analysis). Ultimately, 10 randomized controlled trials met inclusion criteria for primary analysis.

The mean ages of participants ranged between 71 - 92 years (Table 1), and the majority were females. The included studies spanned eight different countries; three were multicenter trials.19,35,36 One study37 included only hospitalized patients, four studies studied institutionalized participants, 19,35,38,40 and five studies evaluated community-dwelling adults.18,36,39,41,42 All studies in community-dwelling adults had mean age <80 years. Four studies specified that the majority of participants had history of either previous fracture or fall,37-39,40 while four specified that most participants did not have history of fractures or falls.18,35,36,41 In all studies where baseline mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were reported, the level in at least one treatment arm was <30ng/ml.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics of Randomized Controlled Trials Included in Meta-Analysis

| Study | Therapy, Dose, Frequency* |

N | Age, mean (years) |

Follow- up (mos) |

How Fall Assessed† |

Baseline/Change in 25-hydroxy- Vitamin D‡ (ng/ml) |

Previous Fracture (%)‡ |

Previous Falls (%)‡ |

Population§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies Included In Primary Analysis | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Bischoff et al, 38 2003 |

I: Cholecalciferol 400 IU bid, Calcium carbonate 600mg bid |

62 | 85 | 3 | O | 12 / 14 | 56 | 24 | Institutionalized elderly awaiting nursing home placement |

|

C: Calcium carbonate 600mg bid |

60 | 84 | 3 | O | 12 / −0.2 | 52 | 23 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Bischoff- Ferrari et al, 42 2006 |

I: Cholecalciferol 700 IU daily, Calcium citrate 500mg daily |

219 | 71 | 36 | Q, P | ♂:33 ; ♀: 28 | Healthy, ambulatory, community- dwelling |

||

| C: Placebo | 226 | 71 | 36 | Q,P | ♂: 33 ; ♀: 25 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Broe et al,40 2007 |

I: Ergocalciferol 200 IU daily |

26 | 92 | 5 | O | 18 | 69 | Institutionalized, very old |

|

|

I: Ergocalciferol 400 IU daily |

25 | 88 | 5 | O | 21 | 68 | |||

|

I: Ergocalciferol 600 IU daily |

25 | 89 | 5 | O | 17 | 64 | |||

|

I: Ergocalciferol 800 IU daily |

23 | 89 | 5 | O | 21 | 65 | |||

|

C: Placebo + 63% took multivitamin |

25 | 86 | 5 | O | 21 | 44 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Burleigh et al,37 2007 |

I: Cholecalciferol 800 IU daily, Calcium carbonate 1200 mg daily |

100 | 82 | 1 | O | 9 / 1 | 26 | 53 | Hospitalized, ill |

|

C: Calcium carbonate 1200 mg daily |

103 | 84 | 1 | O | 10 / 0 | 26 | 48 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Dukas et al,41 2004 |

I: Alfacalcidol 1μg daily | 192 | 75 | 9 | D | 30 | 5 | Ambulatory, community- dwelling |

|

| C: Placebo | 186 | 75 | 9 | D | 28 | 13 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Flicker et al,35 2005 |

I: Ergocalciferol 10,000 IU qweek then 1,000 IU daily + Calcium carbonate 600mg daily |

313 | 84 | 24 | D | Median ≤16 | 27 | Institutionalized with vitamin D level between 25-90 ng/ml |

|

|

C: Calcium carbonate 200mg daily |

312 | 83 | 24 | D | Median ≤16 | 24 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Graafmans et al,19 1996 |

I: Cholecalciferol 400 IU daily |

177 | 83 | 7 | D, Q | Institutionalized | |||

| C: Placebo | 177 | 83 | 7 | D, Q | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Pfeifer et al,18 2000 |

I: Cholecalciferol 400IU bid, Calcium carbonate 600mg bid |

70 | 75 | 2 | Q | 26 / 40 | 0 | Ambulatory, community- dwelling, vitamin D <50 ng/ml |

|

|

C: Calcium carbonate 600mg bid |

67 | 75 | 2 | Q | 26 / 18 | 0 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Pfeifer et al,36 2009 |

I: Cholecalciferol 400 IU bid, Calcium carbonate 500mg bid |

122 | 76 | 12 | D | 22 | 0 | Ambulatory, community- dwelling, vitamin D <50 ng/ml |

|

|

C: Calcium carbonate 500mg bid |

120 | 77 | 12 | D | 22 | 0 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Prince et al, 39 2008 |

I: Ergocalciferol 1,000IU daily, Calcium citrate 500mg bid |

151 | 77 | 12 | Q | 18 | 60 | Community- dwelling, recruited from emergency room/ home nursing, vitamin D <24 ng/ml |

|

|

C: Calcium citrate 500mg bid |

151 | 77 | 12 | Q | 18 | 58 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Studies Included In Post-hoc Analysis | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Gallagher et al,46 2001 |

I: Calcitriol 0.25 ug BID + Calcium 500-1000 mg daily |

123 | 72 | 36 | Q | 31 | 28 | Healthy, community- dwelling women; primary outcome bone mineral density |

|

|

I: Estrogen + Provera + Calcium 500-1000 mg daily |

121 | 72 | 36 | Q | 31 | 17 | |||

|

I: Calcitriol 0.25 ug BID + Estrogen + Provera + Calcium 500-1000 mg daily |

122 | 71 | 36 | Q | 32 | 16 | |||

|

C: Placebo + Calcium 500-1000 mg daily |

123 | 71 | 36 | Q | 32 | 14 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Grant et al,44 2005 |

I: Ergocalciferol 800 IU daily |

1343 | 77 | 60 | Q | 100 | Community- dwelling,recruited from fracture clinic/orthopedic ward; primary outcome fracture |

||

|

I: Ergocalciferol 800 IU +Calcium 1000 mg daily |

1306 | 77 | 60 | Q | 100 | ||||

| I: Calcium 1000 mg daily | 1311 | 78 | 60 | Q | 100 | ||||

| C: Placebo | 1332 | 77 | 60 | Q | 100 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Harwood et al,45 2004 |

I: Cholecalciferol 800 IU daily + Calcium 1000 mg daily |

29 | 83 | 12 | Q | 12 / 8 | 100 | Community- dwelling, recruited <7 days after hip fracture surgery |

|

| C: None | 25 | 81 | 12 | Q | 11 / −0.1 | 100 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Law et al,48 2006 |

I: Ergocalciferol 1100 IU daily |

1762 | 85 | 10 | D | Institutionalized, recruited from residential care homes |

|||

| C: None | 1955 | 85 | 10 | D | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Latham et al,43 2003 |

I: Ergocalciferol 300,000 IU single oral dose (1600 IU daily) |

108 | 80 | 6 | D | 15 / 9 | 44 | 57 | Frail, hospitalized in acute care or rehabilitation facilities |

| C: Placebo | 114 | 79 | 6 | D | 19 / 0 | 43 | 55 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Porthouse et al,47 2005 |

I: Cholecalciferol 800 IU daily + Calcium 1000mg daily + Leaflet |

1321 | 77 | 36 | Q | 59 | 34 | Community- dwelling women, ≥1 risk factor for fracture; primary outcome fracture |

|

| C: Leaflet | 1993 | 77 | 36 | Q | 58 | 34 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Trivedi et al,20 2003 |

I: Cholecalciferol 100,000 IU every 4 months (800 IU daily) |

1027 | 75 | 48 | Q | Community dwelling British doctors; primary outcome fracture and mortality |

|||

| C: Placebo | 1011 | 75 | 48 | Q | |||||

I=intervention arm, C=control arm

O=observed; D=Diary; P=postcard; Q=questionnaire

if reported

primary outcome was falls unless otherwise indicated.

All intervention arms were compared to either placebo or calcium. All studies were parallel group design and had two arms (intervention and control) except for one study40 which randomized patients to five treatment arms based on vitamin D dose(200-800 IU) and a placebo arm. Seven studies had intervention arms which included adjunctive calcium supplementation (500 -1200mg);18,35-39,42 while most of these also included calcium supplementation in the control arm, one study used placebo in the control arm.42 The remaining three trials compared vitamin D versus placebo.19,40,41 There were three types of vitamin D (cholecalciferol, ergocalciferol, alfacalcidol) used. Treatment duration ranged between 1-36 months and native vitamin D dosage ranged between 200-1000 IU. Compliance ranged between 86-98% for most studies where this information was reported.18, 35,37,40 The follow-up rate was >85% in studies that reported completion rates.18,35,37,39-41 Two studies reported involvement with industry sponsorship.18,36

Falls were a primary outcome in all included studies and were ascertained by direct observation in three studies,37,38,40 questionnaire alone in two studies,18,39 and fall diaries in three studies.35,36,41 Two studies used a combination of methods including questionnaire and postcard42 and questionnaire and diary.19

Assessment of Methodological Quality

In general, methodological quality of included studies was good (Table 2). All studies had clearly defined eligibility criteria, therapies, and reliable fall ascertainment. All studies were double-blind except for one19 which did not clearly mention the method of blinding and may be subject to detection bias; in this study, a subgroup of participants were followed as part of a larger, observational study and randomized to vitamin D treatment. Sequence generation was adequately described in all studies except four.18,19,36,42 In three of these studies,18,19,36 there was insufficient information on allocation concealment, which may make them vulnerable to selection bias. At least one of the following was absent or unclear in three studies:19,36,42 incomplete outcome data addressed, similar rates of follow-up and reasons for loss to follow-up, rendering these studies vulnerable to attrition bias. Reasons for exclusion were described in all studies except one.19 Baseline characteristics were dissimilar between study arms in two studies due to differences in previous fracture rate35 or anticoagulant use,41 and were unclear in two studies.19,37

Table 2.

Qualitative Analysis of Included Studies*

| Adequate Sequence Generation Described |

Allocation Conceal- ment Described |

Assessor Blinding |

Incomplete Outcome Data Addressed |

Free From Other Bias |

Eligibility Criteria Defined |

Excluded Patients Described (Number & Reason) |

Rates of Follow- up Similar |

Describe Reasons for Loss to Follow- up |

Describe all Therapies Clearly |

Prospective Sample Size Justification |

Similar Baseline Charact- eristics Between Groups |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies Included In Primary Analysis | ||||||||||||

| Bischoff et al,38 2003 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bischoff- Ferrari et al,42 2006 |

U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Broe et al,402007 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Burleigh et al,37 2007 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Dukas et al,41 2004 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Flicker et al,35 2005 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Graafmans et al,19 1996 |

U | U | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | U | U |

| Pfeifer et al,18 2000 |

U | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pfeifer et al,36 2009 |

U | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Prince et al,39 2008 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Grant et al,44 2006 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gallagher et al,46 2001 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Harwood et al,45 2004 |

Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Law et al,48 2006 |

Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Latham et al,43 2003 |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Porthouse et al,47 2005 |

Y | U | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y |

| Trivedi et al,20 2003 |

U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | Y |

Y=yes, N=no, U=unclear

Statistical methods were described in all studies. Prospective sample size justification was not clearly stated in three studies19,40,42 while intention-to-treat analysis was clearly stated in all but one study.19

Evidence Synthesis for Primary Analysis

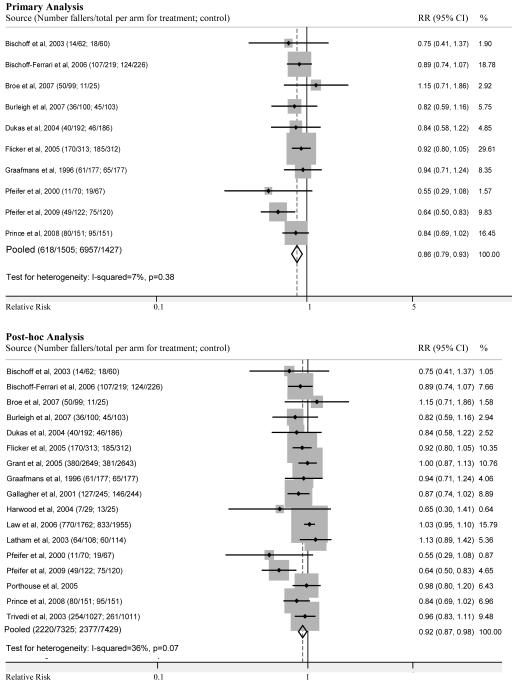

The 10 studies included 2,932 participants (Figure 2). There was a statistically significant effect of vitamin D treatment on falls, with a pooled relative risk of 0.86 (95% CI 0.79-0.93; I2=7%; p=0.38). From the pooled risk difference, the number needed to treat was 15, resulting in 68.1 (35.1-98.5) out of 1000 falls avoided by vitamin D treatment.

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing the risk of falling in vitamin D treated groups and control groups in the primary (above) and post-hoc (below) analyses. Squares represent the relative risk (RR) of falling in the treated groups versus those in control groups. The size of the square is proportional to the size of the trials, and error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI). The diamond shape represents the pooled relative risk, which was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79-0.93) for the 10 studies in primary analysis and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.87-0.98) for the 17 studies in post-hoc analysis, which included 7 additional studies that did not have explicit fall definitions. Note that pooled numbers in post-hoc analysis do not include Porthouse et al. (2005) since this study only reported a relative risk of falling. Relative weight (%) of each study in pooled analysis is also indicated.

In subgroup analysis (Table 3), we found a significant reduction in number of falls in the following subgroups: community-dwelling participants (age<80 years)18,36,39,41,42 (RR 0.79, 0.69-0.92); majority of participants without history of fracture or fall18,35,36,41 (RR 0.77,0.62-0.97); adjunctive calcium supplementation18,35-39,42 (RR 0.83,0.75-0.92); and duration >6 months19,35,36,39,41,42 (RR 0.86,0.78-0.94). We found that dose≥800IU18,35-39,40 (RR 0.80,0.70-0.91) was more favorable than dose<800IU19,40,42 (RR=1.01,0.85-1.20) but did not reach statistical significance (intergroup p=0.06). Treatment with cholecalciferol18,19,36-38,42 (RR 0.80,0.69-0.93) was more favorable than ergocalciferol35,39,40 (RR 0.89,0.80-1.00) but not statistically significant (intergroup p=0.34). Treatment with alfacalcidol41 did not result in a statistically significant reduction in risk of falls (RR 0.84,0.58-1.22).

Table 3.

Subgroup Analyses for Vitamin D Treatment and the Prevention of Falls

| Subgroup | Number of studies |

Number of participants | Relative risk of falling (95% confidence interval) |

I2 , % | P value§ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | |||||

| Studies Included In Primary Analysis | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Adjunctive calcium therapy* | ||||||

| Yes18,35-39,42 | 7 | 1,037 | 1,039 | 0.83 (0.75, 0.92) | 22 | 0.51 |

| No19,40,41 | 3 | 468 | 388 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 0 | |

| Type of Vitamin D | ||||||

| Ergocalciferol35,39,40 | 3 | 512 | 488 | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) | 0 | ref |

| Cholecalciferol18,19,36-38,42 | 6 | 750 | 753 | 0.80 (0.69, 0.93) | 24 | 0.34‡ |

| Alfacalcidiol41 | 1 | 192 | 186 | 0.84 (0.58, 1.22) | – | 0.80‡ |

| Participant Dwelling and Age† | ||||||

| Community-dwelling, age <80 years18,36,39,41,42 |

5 | 754 | 750 | 0.79 (0.69, 0.92) | 29 | 0.20 |

| Hospitalized or institutionalized, age ≥80 years19,35,37,38,40 |

5 | 751 | 677 | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01) | 0 | |

| History of Fracture or Fall (in majority of participants) if reported |

||||||

| Yes37-40 | 4 | 412 | 339 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.98) | 0 | 0.68 |

| No18,35,36,41 | 4 | 697 | 685 | 0.77 (0.62, 0.97) | 59 | |

| Duration of vitamin D treatment | ||||||

| ≤6 months18,37,38,40 | 4 | 331 | 255 | 0.79 (0.62, 1.01) | 0 | 0.89 |

| >6 months19,35,36,39,41,42 | 6 | 1,174 | 1,172 | 0.86 (0.78, 0.94) | 21 | |

| Dose of oral vitamin D | ||||||

| <800 IU19,40,42 | 3 | 472 | 478 | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 21 | 0.06 |

| ≥800 IU18,35-40 | 7 | 841 | 838 | 0.80 (0.70, 0.91) | 31 | |

|

| ||||||

| Studies Included In Post-Hoc Analysis | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Adjunctive calcium therapy* | ||||||

| Yes18,35-39,42,44,45,46,47 | 11 | 3,938 | 4,622 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.92) | 0 | 0.001 |

| No19,20,40,41,43,44,48 | 7 | 4,708 | 4,800 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.07) | 0 | |

| Type of Vitamin D | ||||||

| Ergocalciferol35,39,40,43,44,48 | 6 | 5,082 | 5,200 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 23 | ref |

| Cholecalciferol18,19,20,36-38,42,45,47 | 9 | 3,127 | 3,792 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | 28 | 0.08‡ |

| Alfacalcidiol or Calcitriol41,46 | 2 | 437 | 430 | 0.86 (0.75, 1.00) | 0 | 0.16‡ |

| Participant Dwelling and Age† | ||||||

| Community-dwelling, age <80 years18,20,36,39,41,42,44-46,47 |

10 | 6,025 | 6,676 | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) | 34 | 0.10 |

| Hospitalized or institutionalized, age ≥80 years19,35,37,38,40,43,48 |

7 | 2,621 | 2,746 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0 | |

| History of Fracture or Fall (in majority of participants) if reported |

||||||

| Yes37-39,40,43-45,47 | 8 | 3,198 | 3,131 | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) | 0% | 0.11 |

| No18,35,36,41,46 | 5 | 942 | 929 | 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) | 46% | |

| Duration of vitamin D treatment | ||||||

| ≤6 months18,37,38,40,43 | 5 | 439 | 369 | 0.93 (0.73, 1.17) | 37 | 0.41 |

| >6 months19,20,35,36,39,41,42,44-46,47,48 | 12 | 8,207 | 9,053 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 42 | |

| Dose of oral vitamin D | ||||||

| <800 IU19,40,42 | 3 | 472 | 478 | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 21 | 0.35 |

| ≥800 IU18,20,35-39,40,43-45,47,48 | 13 | 7,737 | 8.589 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | 50 | |

Calcium therapy given in both intervention and control arms, except for three studies42,45, 47 where only given in intervention arm. For studies with multiple arms44, vitamin D alone arm was compared to placebo arm and vitamin D with calcium arm was compared to calcium arm.

All studies in community-dwelling individuals had mean age <80 years except for one in post-hoc analysis45; all studies in hospitalized or institutionalized individuals had mean age >80 years except for one in post-hoc analysis43.

Compared to ergocalciferol.

P value indicates difference between subgroups.

In meta-regression, we found no significant linear association of vitamin D dose (p=0.13) or treatment duration (p=0.38) with relative risk of falls. Further, when we restricted the meta-regression only to studies of dose<800 IU, there was no significant linear association of dose with risk of falling (p=0.35). The absence of a linear association begs the question of whether an adequate minimal dose of vitamin D exists. Further analyses demonstrated that the pooled RR for doses≥400 IU18,19,35-39,40,42 (RR=0.86, 0.77-0.96) was slightly less favorable but remained significant compared to the pooled RR for doses≥800 IU18,35-39,40 (RR=0.80, 0.70-0.91). In contrast, no significant reductions in fall risk were observed at a dose of 200 IU40 (RR=1.31, 0.76-2.28). A minimum vitamin D dose of 400 IU may be needed to achieve significant benefits in fall reduction.

In sensitivity analysis, we examined the effect estimate using only those studies with similar baseline characteristics.18,36,38,39,40,42 The RR was 0.81 (95% CI 0.69, 0.94), comparable to the overall RR when all 10 studies were included.

There was no evidence of significant publication bias according to the Begg’s and Egger’s tests for the 10 studies included in primary analysis.

In the included studies, adverse events were minimal or not reported. Hypercalcemia was reported to among 0-3% of participants in four studies,37-39,41 but not addressed in the remaining studies. Hypercalciuria was not described in any of the included studies.

Post-hoc Analysis

We conducted a post-hoc analysis including all studies that had falls as an outcome, regardless of whether the definition of falls was explicitly given in the publication, to test the robustness of this inclusion criterion. The post-hoc analysis included 17 studies (10 studies with and 7 studies without explicit fall definitions); a summary of the 7 additional studies is provided in Table 2.

In contrast to studies that were included in our primary analysis, a few studies included participants at high risk for falls such as individuals that were frail43 or all had history of fracture.44,45 Vitamin D interventions were similar except for one study that used calcitriol, estrogen and provera in the treatment arms46. The vitamin D regimen varied in these studies from 800–1100IU daily to 100,000IU every four months. The studies tended to be of longer duration (6–60 months). Falls were not a primary outcome in all studies.20,44,46,47

With regards to study quality, these studies generally had good methodological quality, similar to those in our primary analysis (Table 3) with a few exceptions. In three studies, placebo was not given, so neither participant nor investigator was blinded.45,47,48 Porthouse et al. (2005)47 may have been subject to attrition bias since reasons for losses to follow-up were not completely described. In this study, falls were self-reported at 6 month intervals, which is not as reliable as questionnaires given every 6 weeks.39 One study had involvement with industry sponsors47 and one study did not provide a flow diagram describing when patients were excluded.20

Among 17 studies, which included 18,068 individuals, the relative risk of falling in the treatment compared to the control group was 0.92 (95% CI 0.87-0.98) with an I-squared of 36% (p=0.07) (Figure 2). For one study,47 only the relative risk estimate for falling was provided.

Given that post-hoc studies had similar quality measures to those in primary analysis, aside from the exceptions listed above, we performed exploratory subgroup analyses (Table 3). We found significant intergroup differences favoring adjunctive calcium therapy18,35-39,42,44,45,46,47 versus none19,20,40,41,43,44,48 (p=0.001), resulting in a 14% fall risk reduction and heterogeneity that completely resolved (I2=0%) in stratified analysis. In post-hoc analyses, treatment with cholecalciferol18,19,20,36-38,42,45,47 (RR 0.86,0.77-0.96) was more favorable than ergocalciferol35,39,40,43,44,48 (RR 0.99,0.92-1.06), but did not reach statistical significance (intergroup p=0.08).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that there is a protective effect of vitamin D supplementation on fall prevention in community dwelling and institutionalized older adults. An overall relative risk of 0.86 (95% CI 0.79-0.93) suggested a 14% reduction in the risk of falls. The effect of vitamin D on fall reduction was significant in several subgroups of individuals: community-dwelling participants with mean age<80 years, adjunctive calcium therapy, no history of fracture/fall, duration>6 months, dose>800 IU, and cholecalciferol therapy. However, we did not find evidence of a linear association between higher doses of vitamin D or longer duration of vitamin D therapy with treatment effect. When we added trials without explicit fall definition into post-hoc analysis, the overall RR was smaller but remained significant (RR 0.92, 0.87-0.98), although the heterogeneity was substantial. In post-hoc analysis, significant intergroup differences favoring adjunctive calcium therapy were found with heterogeneity that completely resolved.

The inference from our work is similar to that of an earlier meta-analysis26 reporting a corrected pooled odds ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.64-0.92) in five studies and a 13% reduction in odds of falling in sensitivity analysis of 10 studies. The magnitude of the effect we report is only slightly less in comparison. Because the fall outcome was common in our study, we believed the odds ratio would overestimate the effect estimate, and chose to analyze our data with relative risks.

There have been two smaller meta-analyses that have shown a statistically significant reduction in fall risk with vitamin D treatment. A meta-analysis of two trials by O’Donnell et al. (2008)25 showed an even more protective effect of active vitamin D (calcitriol, alfacalcidol) with a 34% reduction in the odds of falling in vitamin D treated groups compared to controls. Another meta-analysis of 11 studies by Richy et al. (2008)24 showed an overall protective effect of 8% but this was mostly due to a statistically significant lower risk of falling in users of active vitamin D (RR 0.79,064-0.96) compared to native vitamin D (RR 0.94,0.87-1.01). In comparison, we found that active vitamin D may have greater benefits compared to ergocalciferol, but similar benefits compared to cholecalciferol.

A recent meta-analysis of eight randomized-controlled studies published by Bischoff-Ferrari, et al. (2009),27 found an overall risk reduction of 13% (RR 0.87,0.77-0.99) with significant heterogeneity (Q test: p=0.05). We report a similar overall risk reduction of 14% in 10 randomized controlled trials but with a relatively more precise estimate (RR 0.86,0.79-0.93) and minimal heterogeneity (I-squared=7%; p=0.38). We similarly found greater benefit with higher dose vitamin D when studies were dichotomized as high or low dose, although in post-hoc analysis the difference became less significant. In our meta-regression analysis containing fewer assumptions, we found no evidence for a linear association of dosage or duration with treatment effect. We also did not exclude studies investigating hospitalized patients. Though hospitalized patients could have comorbid conditions that predispose them to falls, the rate of falling among controls was similar between hospitalized patients37 (fall rate=44%) and community-dwelling or institutionalized persons18,19,35,36,38,39,40-42 (fall rates ranging between 28-59%). Vitamin D treatment reduced the risk of falling by 18% (RR 0.82,0.59-1.16) in hospitalized patients 37, within the range of RRs reported by other studies included in this meta-analysis. Further, our rigorous quality assessment allowed us to identify more high-quality studies that had been dismissed. As a result, we were able to perform subgroup analyses that other meta-analyses may have been underpowered to conduct or did not investigate.

There are limitations to this systematic review and meta-analysis. We were not able to investigate whether the treatment of vitamin D on fall prevention would also apply to populations that were not vitamin D deficient at baseline since all included studies had vitamin D levels that were ≤30ng/ml. The ascertainment of falls varied among studies which may have contributed to inaccuracies in outcomes reporting. While we did not examine how many falls subsequently led to fracture, the distinction between falls that are injurious versus non-injurious may be important. Though self-reported compliance was relatively high in most studies where it was reported (86-98%), a more objective marker might have been changes in endogenous vitamin D levels before and after treatment. However, few studies explicitly provided this information18,37,38 and vitamin D changes were highly variable (0-40ng/ml). Calibration of vitamin D across different assays and laboratories is problematic with mean between laboratory variation ranging from 2.9-5.2ng/ml;49 therefore, without proper standardization, such information may not be reliable. Lastly, subgroup analyses are observational by nature and may be subject to confounding by study-level characteristics; these exploratory analyses require confirmation in randomized clinical trials comparing benefits among particular patient populations or treatment regimens.

Our post-hoc analysis of 17 studies increased the number of individuals in our analysis by six-fold, yet our treatment effect remained significant though smaller in magnitude, despite including studies without an explicit fall definition. We chose to report this as a post-hoc analysis for several reasons. First, it was important to retain the initial eligibility criteria formulated in our protocol. Second, the addition of studies without an adequate fall definition increased I-squared considerably, suggesting that these studies may be more heterogeneous. Third, falls can be described differently and result in inconsistencies if not explicitly defined. Lastly, the post-hoc analysis might have underestimated the true effect of vitamin D by including some studies that assessed falls as a secondary outcome and that were not double-blinded. However, given that our quality assessment suggested that studies in post-hoc analysis were otherwise similar to those in primary analysis, we performed exploratory subgroup analysis to better discern possible differences. A limitation of any pooled analysis is that results will be weighted more towards larger studies (with smaller standard errors); however, in analyses with many participants such as ours, the relative influence of each study may be less.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis has provided a comprehensive update of prior reviews, and identified two additional randomized controlled trials37, 47 not previously examined. We have also provided a comprehensive quality assessment of all studies included in our meta-analysis, allowing us to identify possible sources of bias. Among 17 studies in post-hoc analysis, we found significant intergroup differences favoring participants given vitamin D with calcium versus vitamin D alone which is a novel finding. Adequate calcium supplementation is necessary for optimal vitamin D action and may explain the greater benefits found with this regimen.

In summary, we have demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation is an effective strategy for reducing falls in older adults and should likely be incorporated into the clinical practice of providers caring for older adults, especially those at risk for falling. While the effect appears to be modest, possibly due to inadequate dosing, vitamin D is inexpensive and well-tolerated; a slight reduction in falls with vitamin D supplementation might lead to a significant decrease in the costs associated with fall morbidity and mortality.

However, there are still several outstanding questions. Research to date has not determined the optimum dose of vitamin D needed to reduce falls. More studies are needed to investigate the sustainability of beneficial effects conferred by vitamin D treatment on falls. Also, the utility of vitamin D treatment in patients who are not vitamin D insufficient is not clear. Studies that are better powered to detect differences in fall reductions by subgroups may provide further insight into selected populations that could most benefit from vitamin D. Lastly, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the effects of vitamin D on fall prevention in hospitalized patients. In the future, investigations on these topics may facilitate the development of effective clinical guidelines regarding the administration of vitamin D for the prevention of falls in older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the following for reviewing early drafts of this manuscript: Todd Brown, M.D., Ph.D, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Edgar Miller III, M.D., Ph.D, Division of General Internal Medicine, and Frederick Brancati, M.D., MHS, Division of General Internal Medicine; the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

R.R.K., J.M., and D.C. were supported by an Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (KL2) Mentored Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (KL2 RR025006). B.S. was supported by an institutional Clinical Hematology Research Development Program (K12) award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institutes of Health (K12 HL087169). R.V. and R.M. were supported by an institutional research training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 90033122).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have potential conflicts of interest with reference to this paper.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding agency had no role in the study design, methods, and subject recruitment; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF, Jackson SL, et al. Circumstances and consequences of falls experienced by a community population 70 years and over during a prospective study. Age Ageing. 1990;19:136–141. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake AJ, Morgan K, Bendall MJ, et al. Falls by elderly people at home: Prevalence and associated factors. Age Ageing. 1988;17:365–372. doi: 10.1093/ageing/17.6.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prudham D, Evans JG. Factors associated with falls in the elderly: A community study. Age Ageing. 1981;10:141–146. doi: 10.1093/ageing/10.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. The effect of falls and fall injuries on functioning in community-dwelling older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M112–119. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.2.m112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000340. CD000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Self-reported falls and fall-related injuries among persons ≥ 65 years—United States, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romer LJ, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing. 1997;26:189–193. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo JA, Friedkin R, Williams CS, et al. Health care utilization and costs in a Medicare population by fall status. Med Care. 1998;36:1174–1188. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, et al. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, et al. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007;297:77–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinnetti ME. Clinical practice: Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:42–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp020719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein MS, Wark JD, Scherer SC, et al. Falls relate to vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in an Australian nursing home and hostel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1195–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young A, Brenton P, Edwards RHT. Analysis of muscle weakness in osteomalacia. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1978;54:31P. doi: 10.1042/cs0540463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holick MF. The Role of Vitamin D for Bone Health and Fracture Prevention. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2006;4:96–102. doi: 10.1007/s11914-996-0028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holick MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorensen OH, Lund B, Saltin B, et al. Myopathy in bone loss of ageing: improvement by treatment with 1 alpha-hydroxycholecalciferol and calcium. Clin Sci (London) 1979;56:157–61. doi: 10.1042/cs0560157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceglia L. Vitamin D and Skeletal Muscle Tissue and Function. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2008;29:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, et al. Effects of a short-term vitamin D and calcium supplementation on body sway and secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1113–1118. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, et al. Falls in the elderly: A prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latham NK, Anderson CS, Reid IR. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on strength, physical performance, and falls in older persons: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1219–1226. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliver D, Connelly JB, Victor CR, et al. Strategies to prevent falls and fractures in hospitals and care homes and effect of cognitive impairment: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007;334:82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39049.706493.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson C, Gaugris S, Sen SS, et al. The effect of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) on the risk of fall and fracture: A meta-analysis. QJM. 2007;100:185–192. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richy F, Dukas L, Schacht E. Differential effects of D-hormone analogs and native vitamin D on the risk of falls: A comparative meta-analysis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:102–107. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donnell S, Moher D, Thomas K, et al. Systematic review of the benefits and harms of calcitriol and alfacalcidol for fractures and falls. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:531–542. doi: 10.1007/s00774-008-0868-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Willett WC, et al. Effect of vitamin D on falls: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1999–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, et al. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;339:b3692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson KA, Dickerson K. Development of a highly sensitive search strategy for the retrieval of reports of controlled trials using PubMed. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:150–153. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchner DM, Cress ME, Wagner EH, et al. The Seattle FICSIT/MoveIt study: The effect of exercise on gait and balance in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:321–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romagnoli E, Mascia ML, Cipriani C, et al. Short and long-term variations in serum calciotropic hormones after a single very large dose of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3015–3020. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins J, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford, UK: 2008. pp. 187–242. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in health care: Meta-analysis in context. BMJ Publishing Group. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flicker L, MacInnis RJ, Stein MS, et al. Should older people in residential care receive vitamin D to prevent falls? Results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1881–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, et al. Effects of a long-term vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls and parameters of muscle function in community-dwelling older individuals. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:315–322. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burleigh E, McColl J, Potter J. Does vitamin D stop inpatients falling? A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2007;36:507–513. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bischoff HA, Stähelin HB, Dick W, et al. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:343–351. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prince RL, Edstin N, Devine A, et al. Effects of ergocalciferol added to calcium on the risk of falls in elderly high-risk women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:103–108. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broe KE, Chen TC, Weinberg J, et al. A higher dose of vitamin d reduces the risk of falls in nursing home residents: A randomized, multiple-dose study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dukas L, Bischoff HA, Lindpaintner LS, et al. Alfacalcidol reduces the number of fallers in a community-dwelling elderly population with a minimum calcium intake of more than 500 mg daily. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Orav EJ, Dawson-Hughes B. Effect of cholecalciferol plus calcium on falling in ambulatory older men and women: A 3-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:424–430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: The Frailty Interventions Trial in Elderly Subjects (FITNESS) J Am Geratric Soc. 2003;51:291–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, et al. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-tredma fractures in elderly people: A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1621–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harwood RH, Sahota O, Gaynor K, et al. The Nottingham Neck of Femur (NONOF) Study. A randomised, controlled comparison of different calcium and vitamin D supplementation regimens in elderly women after hip fracture: The Nottingham Neck of Femur (NONOF) Study. Age Ageing. 2004;33:45–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallagher JC, Fowler SE, Detter JR, et al. Combination treatment with estrogen and calcitriol in the prevention of age-related bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3618–28. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C, et al. Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ. 2005;330:1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Law M, Withers H, Morris J, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and the prevention of fractures and falls: Results of a randomised trial in elderly people in residential accommodation. Age Ageing. 2006;35:482–486. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binkley N, Krueger D, Gemar D, et al. Correlation among 25-hydroxy-Vitamin D assays. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1804–1808. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]