Abstract

One of the most adaptive immune responses is triggered by specific T-cell receptors (TCR) binding to peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC). Despite the availability of many prediction servers to identify peptides binding to MHC, these servers are often lacking in peptide–TCR interactions and detailed atomic interacting models. PAComplex is the first web server investigating both pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces to infer peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens of a query. This server first identifies significantly similar TCR–pMHC templates (joint Z-value ≥ 4.0) of the query by using antibody–antigen and protein–protein interacting scoring matrices for peptide-TCR and pMHC interfaces, respectively. PAComplex then identifies the homologous peptide antigens of these hit templates from complete pathogen genome databases (≥108 peptide candidates from 864 628 protein sequences of 389 pathogens) and experimental peptide databases (80 057 peptides in 2287 species). Finally, the server outputs peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens of the query and displays detailed interacting models (e.g. hydrogen bonds and steric interactions in two interfaces) of hitTCR-pMHC templates. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed server can achieve high prediction accuracy and offer potential peptide antigens across pathogens. We believe that the server is able to provide valuable insights for the peptide vaccine and MHC restriction. The PAComplex sever is available at http://PAcomplex.life.nctu.edu.tw.

INTRODUCTION

An immune system protects an organism from diseases by identifying and killing pathogens (1). One of the most adaptive immune responses is triggered by specific T-cell receptors (TCRs) binding to peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC) molecules. An increasing number of available binding peptide antigens that are reliable (2–4) and high-throughput experiments that provide systematic identification of pMHC interactions explain the growing requirement for fast and accurate computational methods for discovering homologous peptide antigens of a new peptide antigen and developing peptide-based vaccines for pathogens.

Many methods have been proposed for predicting pMHC interactions. These methods can be roughly divided into the sequence-based methods such as motif matching (5,6), matrix methods [e.g. SYFPEITHI (7), MAPPP (8), IEDB (9)] and machine learning approaches [e.g. SVMHC (10)]; and structure-based approaches [e.g. PREDEP (11) and MODPROPEP (12)]. However, these methods are often lack of the TCR and pMHC binding, which is critical to trigger adaptive immune responses. Since the increasing number of TCR–pMHC crystal structures to investigate both pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces provides further insights for understanding TCR–pMHC interactions and binding mechanisms. Additionally, discovering homologous peptide antigens (called peptide antigen family) to a known peptide antigen often provides a valuable reference for efforts to elucidate the functions of a new peptide antigen.

To address these issues, we propose the PAComplex server for predicting TCR–pMHC interactions and inferring antigen families across organisms of a query protein or a set of peptides. To our best knowledge, PAComplex is the first web server investigating both pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces to infer peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens of a query. Additionally, peptide antigen families are derived from a complete pathogen genome database (≥108 peptide candidates from 389 pathogens) and experimental peptide databases to demonstrate the feasibility of the PAComplex server and increase the number of potential antigens. Moreover, for a peptide antigen family, the amino acid composition and conservation are evaluated at each position. Experimental results demonstrate that the server can improve the peptide antigen prediction accuracy and is useful for identifying peptide antigen families by using two interfaces of TCR–pMHC structures. Furthermore, the proposed server provides a valuable reference for efforts to develop peptide vaccines and elucidate MHC restriction and T-cell activation.

METHOD AND IMPLEMENTATION

Homologous peptide antigen

The concept of homologous peptide antigen is the core of this server. We define the homologous peptide antigen (p′) of the peptide (p) in template complex as follows: (i) p and p′ can be bound by the same MHC forming pMHC and p′MHC, respectively, with the significant interface similarity (ZMHC ≥ 1.645); (ii) pMHC and p′MHC can be recognized by the same TCR with significant peptide-TCR interface similarity (ZTCR ≥ 1.645); and (iii) TCR-pMHC and TCR-p′MHC share significant complex similarity (joint Z ≥ 4.0). The joint Z-value (Jz) is defined as

| (1) |

The ZMHC and ZTCR of a TCR-p′MHC candidate with interaction score (E) can be calculated by (E–µ)/σ, where µ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation from 10 000 random interfaces (Supplementary Figure S1). For a TCR–pMHC template collected from Protein Data Bank (PDB), these 10 000 random interfaces are generated by substituting with another amino acid according to the amino acid composition derived from UniProt (13). Here, JZ ≥ 4.0 is considered a significant similarity according to the statistical analysis of 41 TCR–pMHC structure complexes; 80 057 experimental peptide antigens; and ≥108 peptide candidates derived from 864 628 protein sequences in 389 pathogens.

Template-based scoring function

We have recently proposed a template-based scoring function to determine the reliability of protein–protein interactions derived from a 3D-dimer structure (14). For measuring the pMHC interaction score, the scoring function is defined as

| (2) |

Where EVDW and ESP denote steric force and special energy (i.e. hydrogen bond energy and electrostatic energy), respectively, according to four knowledge-based scoring matrices (14) which have a good achievement between pMHC and protein–protein interactions. Esim refers to the peptide similarity score between p and p′.

To model EVDW and ESP of the peptide-TCR interactions, we developed a new residue-based matrix (Supplementary Figure S2) because the peptide-TCR interface resembles antigen–antibody interactions and differs from protein–protein interfaces (15,16). The matrix is derived from anon-redundant set which consists of 62 structural antigen–antibody complexes (including 131 interfaces) constructed by Ponomarenko et al. (17). According to this matrix, the peptide-TCR (antigen–antibody) interface prefers aromatic residues (i.e. Phe, Trp and Tyr), which interact with aliphatic residues (i.e. Ala, Val, Leu, Ile and Met) or long side-chain polar residues (i.e. Gln, His, Arg, Lys and Glu), to form strong van der Waals (VDW) forces (yellow boxes). Additionally, the scores are high if basic residues (i.e. Arg and Lys) interact to acidic residues (i.e. Asp and Glu). Conversely, the scores are low (purple box) when non-polar residues interact with polar residues.

Overview

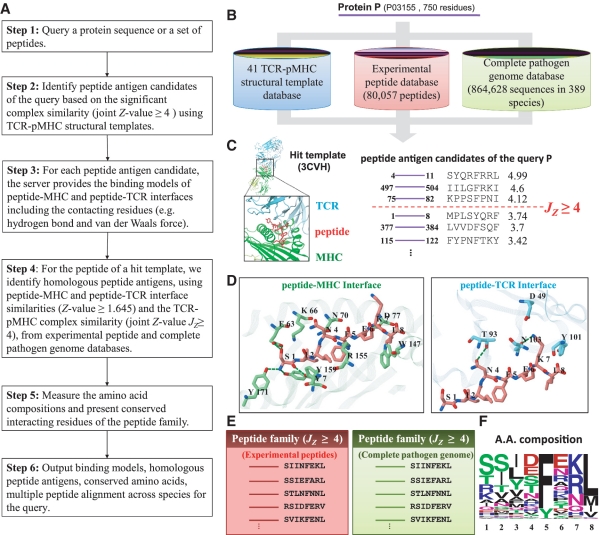

Figure 1 shows the details of the PAComplex server to predict peptide antigens and search the template-based homologous peptide antigens of a query protein sequence (or a set of peptides) by the following steps (Figure 1A). The server initially divides the query protein sequence into fix length (ranging from 8 to 13) peptides based on selected MHC class I allele and templates. Each peptide (p′) is then aligned to the bound peptide (p) of TCR–pMHC templates collected from PDB. Next, the peptide antigen is examined by utilizing the template-based scoring function to statistically evaluate the complex similarity (Jz ≥ 4.0) between TCR–pMHC and TCR-p′MHC (Figure 1B and C). For each peptide antigen, the server introduces the potential TCR–pMHC binding models and the detailed residues interactions (e.g. hydrogen bonds and VDW forces) of pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces (Figure 1D). For the hit templates, the server identifies the homologous peptide antigens with Jz ≥ 4.0 from an experimental peptide database (80 057 peptides in 2287 species) and a complete pathogen genome database (≥108 peptide antigen candidates with Jz ≥ 1.645 derived from 864 628 protein sequences of 389 pathogens) (Figure 1B and E). For a peptide antigen family, we measure the amino acid composition and conservation at each position (Figure 1F) by WebLogo program (18). Finally, this server provides peptide antigens, visualization of the TCR–pMHC interaction models, and peptide antigen families with conserved amino acids.

Figure 1.

Overview of the PAComplex server for peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens search using protein P of HBV as the query. (A) Main procedure. (B) Template-based scoring function to infer the peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens through structural templates, experimental peptides and complete pathogen genome databases. (C) Peptide antigen candidates of the query using hit TCR–pMHC complex templates. (D) Atomic binding models with hydrogen bonds (green dash lines) of both pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces. (E) Peptide antigen families of the query from the experimental peptide and complete pathogen genome databases. (F) Amino acid compositions (profiles) of the homologous peptide antigens.

INPUT, OUTPUT AND OPTIONS

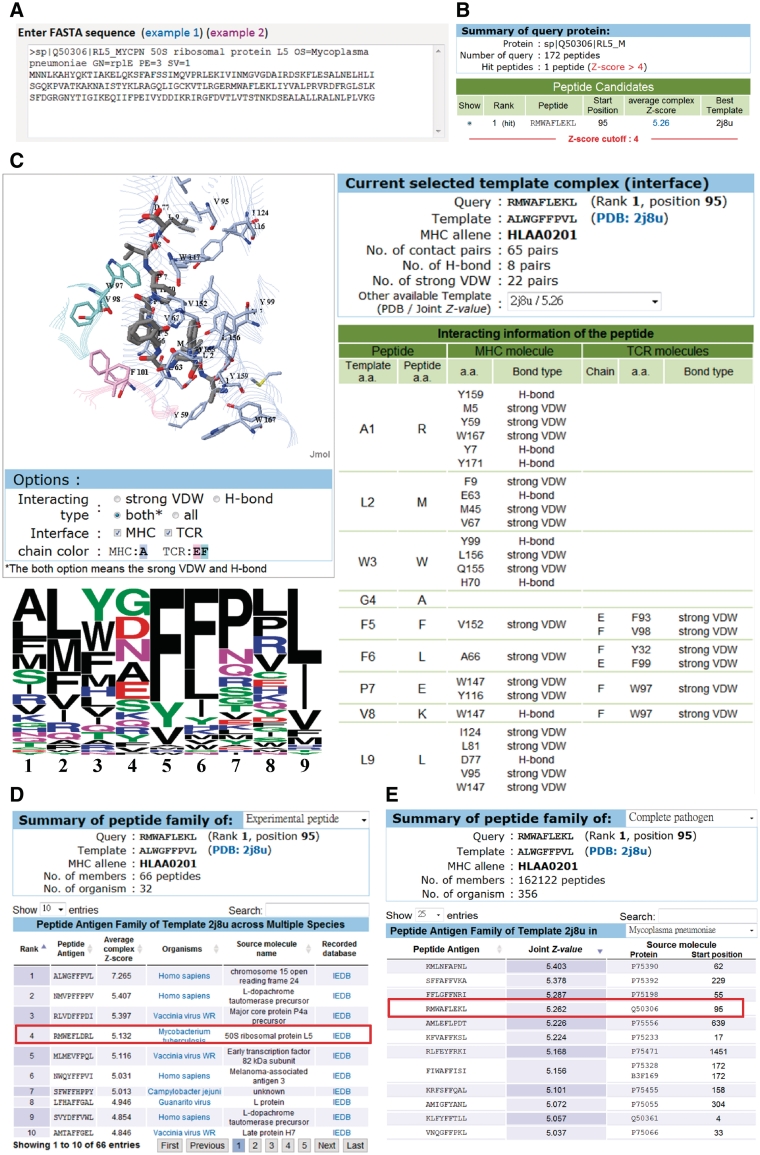

The PAComplex server is easy to use (Figure 2). Users input a protein sequence in FASTA format (or a set of fix-length peptides) and select the parameters (e.g. MHC class I allele and templates) (Figure 2A). The PAComplex server typically infers peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens of the query within 4 s if the sequence length is ≤300. For a query, PAComplex shows the detailed atomic interactions and binding models using Jmol and amino acid profiles (Figure 2C) of homologous peptide antigens from experimental peptide (Figure 2E) and complete pathogen genome databases (Figure 2D). For each peptide antigen, PAComplex also presents the source proteins, organisms and experimental data. In addition, users can download summarized results of query peptides or protein sequences, the modeling TCR–pMHC complex, template structure of TCR–pMHC and peptide family of the template.

Figure 2.

PAComplex server search results using 50S ribosomal protein L5 (rplE) of M. pneumonia as the query. (A) User interface for inputting the query protein sequence, MHC class I allele, and templates. (B) The peptide antigen candidates (Jz ≥ 4.0) of the query. (C) Detailed atomic interactions and binding models with hydrogen bond residues and strong VDW forces. Peptide antigen families from (D) experimental peptide database and (E) complete pathogen genome database, respectively.

Example analysis

Protein P of hepatitis B virus

While affecting over 350 million people worldwide, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a leading cause of liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinoma (19,20). Figure 1 shows the PAComplex derived results using protein P [UniProt (13) accession number: P03155, 750 residues divided into 743 8-mer peptides] of HBV genotype D as the query. Protein P, a multifunctional enzyme, converts the viral RNA genome into dsDNA in viral cytoplasmic capsids. This enzyme displays a DNA polymerase activity that can replicate either DNA or RNA templates, and a ribonuclease H (RNase H) activity that cleaves the RNA strand of RNA–DNA heteroduplexes in a partially processive 3′- to 5′-endonucleasic mode (21,22). For this query, the PAComplex server found three hit peptide antigen candidates (Jz ≥ 4.0; Figure 1C) and 73 homologous peptide antigens in 21 organisms (Supplementary Figure S3A) by using H-2Kb-peptide-TCR template [PDB entry 3 CVH (23)] and the experimental peptide database. Among these three hit peptides, the peptide 497–504 (IILGFRKI) recorded in IEDB (4) is the epitope of protein P and PAComplex presents its binding models and detailed residue interactions of peptide-TCR and pMHC interfaces (Figure 1D). Position 1of the homologous peptide antigens prefers the polar residues (e.g. Ser, Thr, Arg and Lys; Figure 1F) and the first position of this peptide (pink) is polar residue Ser forming five hydrogen bonds with residues Tyr7, Glu63 and Tyr171 on MHC molecule (green) (Figure 1D). Additionally, position 7 (Lys) of the homologous peptide antigens prefers the positive residues (Arg and Lys, Figure 1F) and Lys7 of this hit peptide forms electrostatic interactions with Asp49 in TCR.

Two other hit peptide antigens 4–11 (SYQRFRRL) and 75–82 (KPPSFPNI) correlate well two homologous peptide antigens (SYQHFRKL and KTPSFPNI), which are epitopes of HBV alpha 1 recorded in IEDB, respectively (orange box in Supplementary Figure S3A). According to the amino acid composition (profile) of this peptide antigen family (Figure 1F), position 7 prefers positive charged residues and positions 5 and 8 prefer non-polar residues. Conversely, the compositions of Positions 2 and 4 are diverse. These two hit antigens match the profile of the antigen family on Positions 1 (polar residues), 5 (conserved residue Phe), 7 (positive or polar residues) and 8 (non-polar residues). For instance, the two hit antigens are conserved on the Position 5 with residue Phe forming strong VDW interactions with MHC [Phe74, Val97, Tyr22, Val9 and Tyr116) and TCR (Phe104) molecules (Supplementary Figure S3B)]. These residue–residue interactions (i.e. Phe-Phe, Phe-Val and Phe-Try) are high scores according to pMHC (14) and peptide-TCR (Supplementary Figure S2) scoring matrices. For peptides SYQRFRRL and SYQHFRKL, they have the positively charged residue type (e.g. Arg and Lys) on Position 7 and different residue types on Position 4. For peptides KPPSFPNI and KTPSFPNI, the only different residue type is located on Position 2. Therefore, these two hit peptides are potential peptide antigens. These results suggest that investigating multiple TCR–pMHC interfaces and the peptide antigen family are useful for predicting peptide antigens and providing valuable insight into MHC restriction and T-cell activation.

50S ribosomal protein L5 (rplE) of Mycoplasma pneumonia

50S ribosomal protein L5 (rplE), interacting with 5S rRNA and tRNA, is an essential protein of M. pneumonia, which is the cause of human walking pneumonia (24). Based on use of the M. pneumonia rplE (Q50306, 180 residues are divided into 172 9-mer peptides) as the query (Figure 2A), the PAComplex server infers one hit candidate (Jz≥ 4.0; Figure 2B), 95–103 (RMWAFLEKL) and its 66 homologous peptide antigens in 32 organisms, based on the HLA-A0201-peptide-TCR template [PDB entry 2J8U (25); Figure 2D]. This server provides the binding model (Figure 2C) and homologous peptide antigens via the experimental peptide database and complete pathogen genome database (Figure 2D and E).

The hit candidate is similar to the Rank 4 peptide (RMWEFLDRL, red box) in the peptide family (Figure 2D). But they have three different amino acid types on Positions 4, 7 and 8 whose amino acid compositions of this family are diverse (Figure 2C). Based on binding models and interactions, Position 4 lacks any hydrogen bonds and strong VDW contacts. On the other hand, the hit peptide correlates well with the amino acid profile on the conserved positions (i.e. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9) forming strong VDW forces (the right-side table of Figure 2C) based on the interactions of both peptide-TCR and pMHC interfaces in HLA-A0201-peptide-TCR template (2J8U). Above results imply that the hit peptide of rplE is a potential antigen-activating immune response. Furthermore, PAComplex provides the potential peptide antigens derived from all proteins of the query M. pneumoniae (Figure 2E) and the other 388 pathogens using a complete pathogen genome database. These potential peptide antigens across pathogens can be useful in identifying specific peptides for the target pathogen for vaccine design.

RESULTS

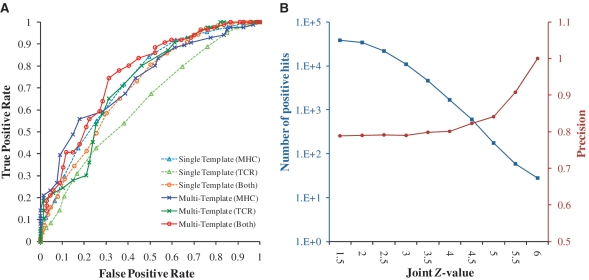

To evaluate the performance of PAComplex for identifying the peptide antigens and peptide antigen families, we selected two peptide sets, termed BothMT (Figure 3A) and CPD (Figure 3B). BothMT consists of 86 positive and 67 negative octamers with experimental data of both H-2Kb and TCR sides collected from IEDB (4). PAComplex aligned these 153 peptides tosix H-2Kb-peptide-TCR complex templates extracted from PDBreleased on 25 December 2010 to evaluate the accuracies of scoring functions on variant conditions (e.g. single template, multiple templates, single side and both sides). The CPD set, which comprises ≥108 peptide candidates (JZ ≥ 1.645) derived from 864 628 protein sequences of 389 pathogens, was used to evaluate the reliability of homologous peptide antigens and it was collected by the following steps: (i) extract 389 pathogens (e.g. bacteria, archaea and virus) recorded in both IEDB and UniProt (13) databases and their respective complete genomes collected from UniProtdatabase (13); (ii) derive the positive and negative data sets from IEDB for these pathogens; and (iii) extract 41 TCR–pMHC complexes from PDB.

Figure 3.

Evaluations of the PAComplex server on BothMT and CPD sets. (A) ROC curves of PAComplex using single and multiple templates with one interface (pMHC and peptide-TCR) and two interfaces of TCR–pMHC complex using BothMT set. (B) Relationship between the distribution of positive hits (blue line) and precision values (red line) with different joint Z-value thresholds using CPD set.

Figure 3A illustrates the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (i.e. true positive and false positive rates) of our scoring functions on single and multiple templates using one interface (i.e. pMHC and peptide-TCR interfaces) and two interfaces (i.e. TCR–pMHC complex). We observed several interesting results: (i) the scoring function using pMHC interface (blue lines) yields a higher accuracy than using peptide-TCR interface (green lines); (ii) using multiple templates (solid lines) is better than using single template (dot lines); and (iii) using two interfaces with multiple templates (red) is the best among these six combinations.

Next, the JZ threshold for reliable homologous peptide antigens is determined by evaluating the PAComplex server on the large-scale CPD data set (Figure 3B).This server was tested on >1010 peptides derived from 864 628 protein sequences of 389 pathogens. Among these peptides, over 108 peptide candidates with JZ ≥ 1.645 were selected for analyzing the relationships between JZ values with both the numbers of positive homologous peptide antigens (blue, recorded in IEDB) and precision (red). When JZ is higher than 4.0, the precision >0.8 and the number of positive antigens exceeds 1600 according to the positive and negative data sets. If the JZ threshold is set to 4.0, the total number of inferring possible peptide antigens surpasses 4 000 000 (Supplementary Figure S4) statistically derived from 41 TCR–pMHC complexes. The amino acid compositions (profiles) of these 1600 positive peptide antigens closely correspond to the ones obtained from peptide antigen families (4 000 000 antigens). These experimental results demonstrate that this server achieves high accuracy and is able to provide potential peptide antigens across pathogens.

CONCLUSIONS

This work demonstrates the feasibility of using the PAComplex server to identify peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens. The proposed server provides detailed atomic interactions, binding models, amino acid compositions of peptide families, source proteins and organisms and experimental data. PAComplex server is the first to infer peptide antigens and homologous peptide antigens by considering two TCR–pMHC interfaces from complete pathogen genome and experimental peptide databases. Experimental results demonstrate that the server is highly accurate and capable of providing potential peptide antigens across pathogens. We believe that PAComplex is a fast homologous peptide antigens search server and is able to provide valuable insights into the peptide vaccine, MHC restriction and T-cell activation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Science Council, partial support of the Aim for Top University (ATU) plan by Ministry of Education and National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX100-10009PI). Funding for open access charge: National Science Council Ministry of Education and National Health Research Institutes.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are grateful to both the hardware and software supports of the Structural Bioinformatics Core Facility at National Chiao Tung University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marrack P, Scott-Browne JP, Dai S, Gapin L, Kappler JW. Evolutionarily conserved amino acids that control TCR-MHC interaction. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:171–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhasin M, Singh H, Raghava GP. MHCBN: a comprehensive database of MHC binding and non-binding peptides. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:665–666. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusic V, Rudy G, Harrison LC. MHCPEP, a database of MHC-binding peptides: update 1997. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:368–371. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vita R, Zarebski L, Greenbaum JA, Emami H, Hoof I, Salimi N, Damle R, Sette A, Peters B. The immune epitope database 2.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D854–D862. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudensky A, Preston-Hurlburt P, Hong SC, Barlow A, Janeway CA., Jr Sequence analysis of peptides bound to MHC class II molecules. Nature. 1991;353:622–627. doi: 10.1038/353622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammer J, Valsasnini P, Tolba K, Bolin D, Higelin J, Takacs B, Sinigaglia F. Promiscuous and allele-specific anchors in HLA-DR-binding peptides. Cell. 1993;74:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuler MM, Nastke MD, Stevanovikc S. SYFPEITHI: database for searching and T-cell epitope prediction. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;409:75–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-118-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakenberg J, Nussbaum AK, Schild H, Rammensee HG, Kuttler C, Holzhutter HG, Kloetzel PM, Kaufmann SH, Mollenkopf HJ. MAPPP: MHC class I antigenic peptide processing prediction. Appl. Bioinformatics. 2003;2:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters B, Sette A. Generating quantitative models describing the sequence specificity of biological processes with the stabilized matrix method. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnes P, Kohlbacher O. SVMHC: a server for prediction of MHC-binding peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W194–W197. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altuvia Y, Sette A, Sidney J, Southwood S, Margalit H. A structure-based algorithm to predict potential binding peptides to MHC molecules with hydrophobic binding pockets. Hum. Immunol. 1997;58:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(97)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar N, Mohanty D. MODPROPEP: a program for knowledge-based modeling of protein-peptide complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W549–W555. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apweiler R, Martin MJ, O'Donovan C, Magrane M, Alam-Faruque Y, Antunes R, Barrell D, Bely B, Bingley M, Binns D, et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D142–D148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YC, Lo YS, Hsu WC, Yang JM. 3D-partner: a web server to infer interacting partners and binding models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W561–W567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudolph MG, Luz JG, Wilson IA. Structural and thermodynamic correlates of T cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:121–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudolph MG, Wilson IA. The specificity of TCR/pMHC interaction. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002;14:52–65. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponomarenko JV, Bourne PE. Antibody-protein interactions: benchmark datasets and prediction tools evaluation. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharya D, Thio CL. Review of hepatitis B therapeutics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;51:1201–1208. doi: 10.1086/656624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:1486–1500. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. The amino-terminal domain of the hepadnaviral P-gene encodes the terminal protein (genome-linked protein) believed to prime reverse transcription. EMBO J. 1988;7:4185–4192. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO J. 1992;11:3413–3420. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mareeva T, Martinez-Hackert E, Sykulev Y. How a T cell receptor-like antibody recognizes major histocompatibility complex-bound peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29053–29059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804996200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyata M. Unique centipede mechanism of Mycoplasma gliding. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:519–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller PJ, Pazy Y, Conti B, Riddle D, Appella E, Collins EJ. Single MHC mutation eliminates enthalpy associated with T cell receptor binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]