Abstract

Objective:

This investigation attempted to determine whether trait and state hostile rumination functioned as risk factors for the relation between acute alcohol intoxication and aggression.

Method:

Participants were 516 social drinkers (252 men and 264 women). Trait hostile rumination was assessed using Caprara's Dissipation—Rumination Scale. Following the consumption of either an alcohol or a placebo beverage, participants were tested on a laboratory task in which electric shocks were received from and administered to a fictitious opponent under the guise of a competitive reaction-time task. Aggression was operationalized as the combined mean responses for shock intensity and duration across all trials. In a subset of the sample (n = 320), state hostile rumination was assessed following the aggression task using a self-report measure.

Results:

As expected, both trait and state measures acted as moderators. Specifically, acute alcohol intoxication was more likely to increase aggression in persons with higher trait and state hostile rumination scores compared with their equally intoxicated lower rumination counterparts.

Conclusions:

This was the first investigation to demonstrate that trait or state rumination significantly heighten the risk of intoxicated aggression. We believe that hostile rumination facilitates intoxicated aggression because ruminators have difficulty diverting their attention away from anger-provoking stimuli and related thoughts, thus making violent reactions more likely. Clinical and public health interventions would benefit by developing strategies to distract ruminative attention away from violence-promoting messages, especially when persons are under the influence of alcohol.

Holding on to anger is like grasping a hot coal with the intent of throwing it at someone else; you are the one who gets burned.—Siddhartha Gautama, The Buddha

Acute alcohol consumption is associated with aggressive behavior. A wealth of survey and epide-miological research suggests that drinking precedes a number of violent criminal behaviors, ranging from marital and child abuse to arguments, threats, and homicides (Berger, 2005; Leonard and Quigley, 1999; Parker, 1995; Testa and Livingston, 2000; Wells et al., 2000). Laboratory experiments also indicate that people who consume alcohol exhibit more aggression compared with those who only consume a placebo beverage (for reviews, see Bushman and Cooper, 1990; Chermack and Giancola, 1997; Ito et al., 1996). These experiments have generally yielded medium effect sizes (Bushman and Cooper, 1990; Ito et al., 1996), suggesting that alcohol is a meaningful but neither a necessary nor sufficient contributor to violent behavior. After all, many people do not become aggressive while drinking, and aggressive behavior does not always involve alcohol consumption. Given the public health ramifications, understanding in which situations and for which people alcohol mostly likely leads to violence is a crucial task.

Researchers have investigated a range of variables that might intensify or attenuate the association between alcohol consumption and aggression. Several individual difference variables that are related to self-control and emotional coping appear to facilitate the alcohol-aggression link. Specifically, alcohol consumption is more likely to result in aggressive behavior for individuals with greater irritability, hostility, dispositional aggression, anger, and poorer anger control (Bailey and Taylor, 1991; Giancola, 2002a, 2002b; Giancola et al., 2003; Godlaski and Giancola, 2009; Parrott and Giancola, 2004; Parrott and Zeichner, 2002). More recent research has also demonstrated that increased avoidance coping interacts with excessive drinking to predict violence (Schumacher et al., 2008).

These moderators can be understood by virtue of the fact that acute alcohol intoxication disrupts the ability to regulate goal-directed behavior (Fillmore, 2003; Lyvers, 2000). From a theoretical stance, the alcohol myopia model posits that alcohol intoxication narrows people's attentional capacity (Steele and Josephs, 1990). Specifically, while in an alcohol-induced “myopic” state, individuals will be more likely to focus their attention only on the most salient internal and external cues. For example, if such persons are confronted with a hostile situation, they will be more apt to focus on salient hostile cues rather than less salient, or peripheral, inhibitory cues (i.e., negative consequences of being aggressive), thus leading to an increased probability of aggression (Giancola et al., 2010). Relatedly, Giancola (2000) argued that alcohol weakens cognitive and inhibitory control, which interferes with the ability to properly appraise a situation, determine a plan of action, and generate alternative behaviors to cope with a potentially hostile situation. From this perspective, dominant behavioral and coping tendencies will influence actions to a greater extent while intoxicated, because logical reasoning and intentional problem-solving will give way to more automatic responses. Therefore, people who already have difficulty with self-control and emotional regulation will be particularly likely to aggress after drinking alcohol, because their reduced attentional capacity will drive them to focus and act on hostile elements in their environment.

One stable emotional coping response that may especially facilitate alcohol-related aggression is rumination. Defined as the tendency to passively perseverate on negative feelings and problems (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), rumination has received recent attention as a maladaptive, trait-based coping strategy. Rather than actively and effectively responding to situations, ruminators spend their time brooding about negative moods and reliving upsetting experiences. Researchers have defined different types of rumination (e.g., depressive, angry, hostile) based on the predominant negative content of the repetitive thoughts (Caprara et al., 2007; Papageorgiou and Wells, 2004; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). Hostile rumination in particular involves perseverating on feelings and intentions associated with seeking revenge and retaliation for perceived provocations (Caprara, 1986; Caprara et al., 2007). Laboratory research has shown a positive relation between trait hostile rumination and aggressive behavior in response to provocation (Caprara et al., 1987; Collins and Bell, 1997). Relatedly, trait angry rumination, which focuses more generally on angry feelings and memories, is also associated with greater self-reported aggression, hostility, and anger and with less forgiveness (Anestis et al., 2009; Barber et al., 2005; Stoia-Caraballo et al., 2008; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001).

Theoretical models of why hostile rumination results in aggressive behavior assume that trait ruminators also engage in high levels of state hostile rumination in response to perceived provocation. Miller and colleagues (2003) proposed that state hostile rumination maintains the activation of anger-related associative networks over time. In line with Berkowitz's (1993) cognitive associative network theory of aggression, prolonged activation makes angry moods and hostile thoughts more accessible and subsequent aggressive behavior more likely. In support of this theory, laboratory studies show that experimentally induced state rumination, generated by a prior provocation from a fictitious opponent, increased anger and aggression toward the individual (Bushman, 2002), even following an 8-hour waiting period between the provocation and the opportunity to retaliate (Bushman et al., 2005; Study 3). In summary, both trait and state hostile rumination result in increased direct physical aggression.

Given the above discussion, we expect that both trait and state hostile rumination will interact with alcohol consumption to elicit heightened physical aggression. Because alcohol intoxication leads to a reliance on more automatic coping responses, when high trait ruminators consume alcohol, they will tend to automatically ruminate in response to provocation. This hostile state rumination should maintain, and even exacerbate, anger and hostility, thus further impairing intoxicated individuals' ability to properly self-regulate behavior. This combination should result in more aggression than that exhibited by drinkers who are not ruminators or by ruminators who have not consumed alcohol. Very few previous studies have examined whether rumination serves as a risk factor for alcohol-related aggression. Borders et al. (2007) found that trait general rumination interacted with self-reported typical alcohol consumption to predict self-reported alcohol-related aggression over a period of 6 months. Specifically, high trait ruminators were more likely to commit aggressive acts after heavy drinking than low ruminators. Unfortunately, this study did not assess the acute effects of alcohol on aggressive behavior, nor did it specifically assess hostile rumination or state rumination. Thus, more research is needed to understand the role of rumination in facilitating alcohol-related aggression.

The present investigation had two primary aims. The first chief aim was to test experimentally whether trait hostile rumination moderates the association between acute alcohol intoxication and aggressive behavior. We hypothesized that participants high in trait hostile rumination would exhibit more aggression than low ruminators. We also predicted that the association between alcohol consumption and aggression would be stronger for persons with higher hostile rumination scores than for their lower scoring counterparts. The second chief aim was to assess whether state hostile rumination also moderates the relation between acute alcohol intoxication and aggression. In keeping with the theory and the arguments put forth above (Berkowitz, 1993; Miller et al., 2003), we predicted that participants with higher levels of state hostile rumination would exhibit more aggression than low state ruminators. More importantly, we also expected that the relation between acute alcohol intoxication and aggression would be stronger for persons with higher levels of state rumination scores during the assessment of physical aggression compared with individuals with lower corresponding scores. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined whether trait or state hostile rumination is a risk factor for acutely intoxicated aggression.

Method

Participants

Participants included 516 healthy social drinkers (49% men) from age 21 to 35 years (M = 23.05, SD = 2.91) who were recruited from the greater Lexington, KY, area through newspaper advertisements and fliers. Social drinking was defined as consuming at least three to four drinks per occasion at least twice per month. The racial composition of the sample was 87% White, 10% African American, 1% Hispanic, and 2% other. Most participants (92%) were not married. The sample had an average of 16 years of education and had an average household income of $61,000. The study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Respondents were initially screened by telephone. Individuals reporting any past or present drug- or alcohol-related problems, contraindications to alcohol consumption, serious head injuries, learning disabilities, or serious psychiatric symptoms were excluded from participation. Regarding drinking problems, persons scoring an 8 or more on the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer et al., 1975) were also excluded. Anyone with a positive breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) test or with a positive urine pregnancy/drug result (i.e., cocaine, marijuana, morphine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates) when he or she arrived at the laboratory was not allowed to participate. Women were not tested between 1 week before menstruation and the beginning of menstruation because hormonal variations associated with menstruation can affect aggressive responding (Volavka, 1995).

Measures

Trait hostile rumination.

Participants completed the Dissipation–Rumination Scale (Caprara, 1986; Caprara et al., 2007), a 20-item inventory (including 5 “filler” items) scored on a 6-point Likert scale with items such as, “I will always remember the injustices I have suffered” and “If somebody harms me, I am not at peace until I can retaliate.” This measure is correlated with irritability and predicts violent behavior (Caprara et al., 1987, 2007). Alpha coefficients range between .79 and .87 (Caprara, 1986; Caprara et al., 2007) and were confirmed in our investigation (α = .87).

State hostile rumination.

A subset of participants completed the Thoughts About Opponent (TAO) questionnaire (Giancola, 2007), an 11-item inventory scored on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert scale. Sample items include “I am having thoughts of revenge or retaliation against my opponent” and “I am thinking that I would like to get back at this person.” Given the absence of such a measure in the literature, we developed our own instrument. We initially pilot tested the TAO on 197 undergraduate students at the University of Kentucky and found an α coefficient of .87. Thus, we began administering the TAO about 40% of the way through the current investigation and have data for 320 participants (50% men). Internal consistency was good in this sample (α = .84). Participants who completed the TAO did not differ from participants who did not complete the TAO on age, gender, ethnicity, or level of trait rumination.

Aggression.

A modified version of the Taylor Aggression Paradigm (TAP; Taylor, 1967) was used to measure aggression. Participants administered and received electric shocks from a fictitious opponent under the guise of a competitive reaction-time task. Participants sat in front a computer screen that instructed them to press, hold, and release the spacebar. They supposedly competed with their opponent to determine who could respond more quickly, with the winner delivering an electric shock to the loser. Winners supposedly controlled the intensity (from the lowest at Level 1 to the highest at Level 10) and duration of the losers' shocks. After each trial, shock intensities set by the participant and the “opponent” were displayed on the computer screen. The task consisted of 34 trials, and participants won half of the trials in a fixed, random pattern (with no more than three consecutive wins or losses). Following a losing trial, participants received 1 of 10 possible shock intensities that each lasted 1 second. All shocks were administered through two finger electrodes. The initiation of trials, administration of shocks, and recording of responses were controlled by a computer. To ensure safety and protect the integrity of the study, the experimenter secretly viewed and heard the participants through a hidden video camera and microphone. We operationalized physical aggression as a combination of the shock intensities (1 through 10) and durations (in milliseconds) that participants administered to their opponent. To calculate this score, we transformed the shock intensity and duration variables into z scores and summed them across all 34 trials. This task has excellent construct validity and has been used for decades as a laboratory measure of aggression for men and women (Giancola and Zeichner, 1995; Taylor, 1967).

Procedure

Participants were instructed to refrain from drinking alcohol 24 hours before testing, to avoid caffeinated beverages the day of the study, to not use recreational drugs from the time of the telephone interview, and to refrain from eating 1 hour before testing. They were told that the investigation concerned the effects of alcohol and personality on reaction time in a competitive situation. After demographic data were obtained, the measure of trait hostile rumination was administered.

Men and women were divided evenly into alcohol and placebo beverage groups. Because of gender differences in body fat composition and alcohol metabolism (Watson et al., 1981), men and women received different alcohol doses. Men received 1 g/kg of 95% alcohol USP mixed at a 1:5 ratio with Tropicana orange juice, whereas women received 0.90 g/kg of alcohol. The placebo beverages contained 4 ml of alcohol in the juice and 4 ml layered on top of the juice, In addition, the rims of the glasses were sprayed with alcohol just before being served. All participants were told that they would consume the equivalent of three to four mixed drinks. Participants were given 20 minutes to consume their beverages. No participant experienced any adverse effects as a result of alcohol consumption. In addition to our alcohol and placebo groups, we could have used a sober control group, in which participants know that they are not consuming alcohol. However, sober and placebo groups do not generally differ on aggression (Bushman and Cooper, 1990; Chermack and Giancola, 1997; Ito et al., 1996). Thus, in recognition of this research, we used only an alcohol group and a placebo group. This choice of groups is ideal for studying the effects of alcohol on aggression while controlling for the belief that alcohol has been consumed.

BrAC levels were measured using the Alco-Sensor IV breath analyzer (Intoximeters Inc., St. Louis, MO) on entry at the laboratory, before the TAP, and after the TAP. Because the aggression-potentiating effects of alcohol are more likely to occur on the ascending limb of the BrAC curve and because a BrAC of at least .08% is effective in eliciting aggression, participants in the alcohol group began the TAP at an approximate BrAC of .09% (see Giancola and Zeichner, 1997). To enhance the effectiveness of the placebo manipulation, participants in the placebo group began the TAP approximately 2 minutes after beverage consumption (e.g., Martin and Sayette, 1993).

Instructions for the TAP were given as participants began drinking their beverages. Everyone was told that his or her opponent was of the same gender and was intoxicated. Pain thresholds and tolerances to the electric shocks were assessed just before beginning the TAP to determine the intensity parameters of the shocks participants would receive. The experimenter gradually increased the level of shock until it became “painful” to the participant. Level 10 was the shock intensity described by each participant as “painful,” Level 9 was 95% of the “painful” level, Level 8 was 90% of the “painful” level, and so on. Levels 1, 5, and 10 were described as “low,” “medium,” and “high,” respectively.

Just before the TAP, participants rated how drunk they felt (0 = not drunk at all to 11 = more drunk than I have ever been), how impaired they were (0 = no impairment to 10 = strong impairment), and whether they believed they had consumed alcohol (no or yes). Immediately following the TAP, they completed the measure of state hostile rumination. Right after the state rumination inventory, participants again answered the same questions about their alcohol consumption. Finally, they were debriefed, and those who received alcohol remained in the laboratory until their BrAC dropped to .04%.

Results

Manipulation checks

BrAC levels.

All participants tested in this study had BrACs of 0% on entering the laboratory. Individuals in the alcohol group had a mean BrAC of .095% (SD = .011) just before beginning the TAP and a mean BrAC of .105% (SD = .016) immediately after the TAP. Participants given the placebo had a mean BrAC of .015% (SD = .011) just before the TAP and a mean BrAC of .007% (SD = .007) immediately after the TAP. There were no gender differences in mean BrACs either before (men = .094%; women = .096%) or after (men = .103%; women = .106%) the TAP.

Aggression task checks.

To verify the success of the TAP deception, participants were asked about their subjective perceptions of their opponent. The deception manipulation appeared successful. Anecdotal reports suggest that the majority of participants did equally well on the task as their opponent and thought that their opponent tried hard to win. Typical descriptions from participants about their opponents included “just an average college student,” “performance was as good as mine,” and “competitive.” Many participants also called their opponents vulgar names and/or gestured obscenely toward them during the task. Previous research has shown that the TAP provides a valid and reliable laboratory measure of aggression (e.g., Giancola and Parrott, 2008) and that, within the ethical limits of the laboratory, participants believe they control an actual weapon that can inflict temporary painful physical harm (i.e., electric shocks) onto their opponent.

Placebo checks.

All participants in the placebo group believed that they drank alcohol. With regard to how drunk they felt (scale range: 0–11), people in the alcohol group reported mean pre- and post-TAP ratings of 4.6 and 5.0, respectively, and those in the placebo group reported mean pre- and post-TAP ratings of 1.8 and 1.9, respectively—pre-TAP ratings: t(514) = -20.1, p < .05; post-TAP ratings: t(514) = -19.7, p < .05. Regarding whether the alcohol they drank caused any impairment (scale range: 0–10), people in the alcohol group reported an average rating of 5.5, and those in the placebo group reported an average of 2.1, t(514) = -19.3, p < .05.

Gender differences

There were no significant gender differences on age, years of education, or yearly salary. Men (M = 1.88, SD = 0.90) and women (M = 1.81, SD = 0.82) did not report significant differences in trait hostile rumination, t(514) = -0.95, n.s. However, women (M = 1.95, SD = 0.60) displayed significantly higher scores than men (M = 1.80, SD = 0.57) on state hostile rumination, t(318) = 2.44, p < .05. An examination of the close means and small effect size (d = 0.25) suggests that this significant difference most likely reflects the large sample size and does not constitute a meaningful effect (Cohen, 1988). Finally, men exhibited significantly more aggression (M = 0.35, SD = 1.44) than did women (M = -0.40, SD = 0.92), t(514) = -7.06, p < .001.

Regression analyses

The major aims of this investigation were to determine whether individual differences in trait and state hostile rumination moderated the alcohol–aggression relation in men and women. To reduce multicollinearity, we standardized the rumination variables (Aiken and West, 1991). Beverage (1 = alcohol, 0 = placebo) and gender (1 = male, 0 = female) were dummy coded. Analyses were conducted using three-step hierarchical regression models, with aggression scores as the dependent variable. All three main effects (beverage group, gender, and hostile rumination) were entered into the models in the first step, followed by two-way interactions in the second step, and then the three-way interaction in the third step. We calculated the interaction terms by multiplying the pertinent first-order variables. We interpreted significant interaction terms by plotting the simple regression slopes and testing to determine whether they differed significantly from zero (Aiken and West, 1991).

Aggression and trait hostile rumination.

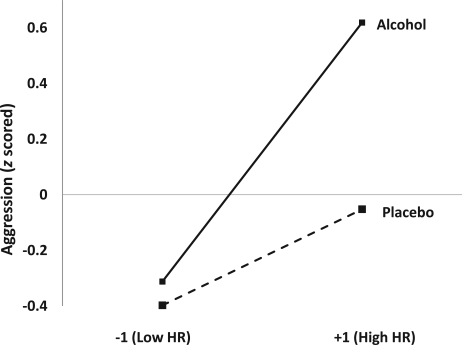

We first tested whether trait hostile rumination moderated the association between beverage group and aggression. The full model was significant, F(7, 508) = 15.61, p < .001, R2 = .20. However, the three-way interaction was not significant, and thus the model was trimmed (the three-way interaction was removed) and recalculated. The second model was also significant, F(6, 509) = 17.29, p < .001, R2 = .19. Within this model, Trait Hostile Rumination × Beverage (b = -0.25, p < .05) and Gender × Beverage (b = 0.41, p < .05) were significant two-way interactions. As seen in Figure 1, the association between high levels of trait hostile rumination and aggression was significantly stronger for the alcohol group (b = 0.47, p < .001) than for the placebo group (b = .17, p < .05). In other words, whereas low hostile ruminators in both beverage groups displayed little aggression, high hostile ruminators in the alcohol group displayed much more aggression than did ruminators in the placebo group. The Beverage × Gender interaction indicated that alcohol led to aggression more for men than for women. This particular interaction has been reported elsewhere in an article specifically on the topic of gender differences (Giancola et al., 2009), and thus we will not plot or discuss it further here. The model containing only the main effects was also significant, F(3, 512) = 26.18, p < .001, R2 = .17. Analyses in the first step revealed that participants in the alcohol group were significantly more aggressive than placebo participants (b = -0.38, p < .001), men were significantly more aggressive than women (b = -0.72, p < .001), and higher hostile rumination scores were significantly associated with increased aggression on the TAP (b = 0.29, p < .001).

Figure 1.

The relation between trait hostile rumination (HR) and aggression under alcohol and placebo conditions: Trait Hostile Rumination × Beverage

Aggression and state hostile rumination.

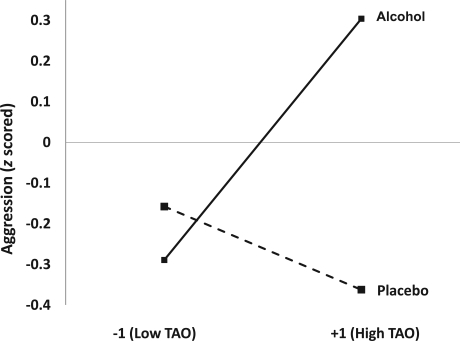

We next ran the same analyses with state hostile rumination as the moderator. The full model was significant, F(7, 312) = 7.98, p < .001, R2 = .15. Once again, the three-way interaction was not significant, and the model was subsequently trimmed and recalculated. The second model was also significant, F(6, 313) = 9.33, p < .001, R2 = .15. Within this model, the State Hostile Rumination × Beverage (b = -0.40, p = <.01) and Gender × Beverage (b = 0.58, p < .05) interactions were significant. As shown in Figure 2, the association between increased hostile state rumination and aggression was significantly stronger for the alcohol group (b = 0.30, p < .01) than for the placebo group (b = -0.10, p = .31). In other words, immediately following the aggression task, intoxicated persons who endorsed more hostile state rumination were significantly more aggressive than their placebo counterparts. As before, participants who reported low state hostile rumination in both beverage groups displayed low levels of aggression. Moreover, whereas the association between hostile state rumination and aggression was significant for people who received alcohol, it was not significant for participants given the placebo. The model containing only the main effects was also significant, F(3, 316) = 13.92, p < .001, R2 = .12. Specifically, intoxicated participants were significantly more aggressive than placebo participants (b = -0.22, p = .066), men were significantly more aggressive than women (b = -0.71, p < .001), and higher state rumination scores were significantly related to increased aggression on the TAP (b = 0.15, p < .05).

Figure 2.

The relation between state hostile rumination (Thoughts About Opponent [TAO] questionnaire) and aggression under alcohol and placebo conditions: State Hostile Rumination × Beverage

Trait and state hostile rumination.

Trait and state hostile rumination were significantly correlated in our sample (r = .23, p < .001), although this effect was small. To examine whether intoxicated trait ruminators engaged in more state rumination than ruminators in the placebo group, we tested the interaction between trait hostile rumination and beverage group on state hostile rumination. The full model was significant, F(3, 316) = 8.16, p < .001, R2 = .07. However, the two-way interaction was not significant (b = -0.15, p = .13). Both alcohol intoxication (b = 0.20, p <.05) and trait hostile rumination (b = 0.28, p < .001) significantly predicted state hostile rumination. Thus, higher trait ruminators and intoxicated persons engaged in more state rumination than low ruminators or placebo participants. However, intoxicated trait ruminators did not report more state rumination than did ruminators in the placebo condition.

Discussion

This study examined the moderating effect of trait and state hostile rumination on the association between acute alcohol consumption and aggressive behavior. The results supported our hypotheses. Averaging over beverage groups, both trait and state rumination were positively related to aggression. These findings add to the current literature showing that hostile rumination is related to heightened aggressive behavior (Bushman, 2002; Caprara et al., 1987; Collins and Bell, 1997).

The findings of greatest importance were that trait and state hostile rumination separately interacted with acute alcohol consumption to predict heightened aggression. Specifically, alcohol consumption resulted in aggressive behavior to a greater degree in persons with higher trait and state rumination. Three-way interactions with gender were not significant, indicating that these interactions apply equally to men and women. These results confirm previous correlational self-report findings (Borders et al., 2007) that trait rumination moderates the alcohol-aggression relation in both men and women. Moreover, this effect also applies to state hostile rumination. We know of no previous studies that have measured state hostile rumination. Thus, this finding constitutes an important contribution.

From a theoretical perspective, it remains unclear how hostile rumination increases intoxicated aggression. Similar to the alcohol myopia model (Steele and Josephs, 1990), people predisposed toward hostile rumination may allocate more attention toward salient “in the moment” hostile experiences, leading them to ruminate more about obtaining revenge or retaliation (Caprara, 1986; Caprara et al., 2007). When individuals are too fixated on these thoughts, they may overlook conflicting internal and external aggression-inhibiting cues. Hostile ruminative thoughts may, in fact, activate a whole host of aggression-related memories, emotions, physiological responses, and behavioral tendencies (Berkowitz, 1993; Miller et al., 2003). Because of its presumed cognitive myopic effects, alcohol may further focus the attention of high hostile ruminators on angering stimuli and related thoughts. Whereas distracting or inhibitory cues attenuate the alcohol–aggression link by redirecting attention away from provoking cues (Giancola and Corman, 2007; Giancola et al., in press; Phillips and Giancola, 2008), increased trait and state hostile rumination may heighten alcohol's effects on aggression by increasing one's focus on more salient and easy-to-process hostile aggression-provoking stimuli.

Rumination may also constitute one of many facilitators of intoxicated aggression that reflect the presence of poor executive functioning. Executive functioning refers to a set of higher order cognitive abilities that include planning, initiation, and regulation of goal-directed behavior (Berger and Posner, 2000; Milner, 1995). Theory and empirical findings suggest that these cognitive skills are necessary for effective emotional and behavioral regulation (Gyurak et al., 2009; Luria, 1980; Morgan and Lilienfeld, 2000). High ruminators in general perform more poorly on various measures of executive functioning, such as concentration, task switching, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility (Davis and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Donaldson and Lam, 2004; Lyubomirsky et al., 2003; Whitmer and Banich, 2007). Therefore, hostile ruminators may ruminate because they have trouble switching their attention away from and/or inhibiting aggression-facilitating thoughts. This tendency for cognitive fixation is likely compounded by alcohol consumption, which also clearly impairs executive functioning (reviewed in Giancola, 2000). Thus, rumination may join the list of variables such as irritability (Giancola, 2002b; Godlaski and Giancola, 2009) and anger control (Parrott and Giancola, 2004) that implicate the importance of self-control and executive functioning in intoxicated aggression.

This is the first aggression study to measure both state and trait hostile rumination. We found that high dispositional hostile ruminators engaged in more state hostile rumination following provocation. These results confirm previous findings that high trait ruminators are more likely to ruminate immediately following a negative emotional stressor than are low trait ruminators (Key et al., 2008). However, trait and state rumination shared only 5% of their variance in our study, suggesting that factors other than dispositional rumination contribute to state rumination. Indeed, intoxicated individuals in our study engaged in more state hostile rumination than did placebo participants, irrespective of ruminative tendencies. Because alcohol is hypothesized to narrow people's attentional capacity (Steele and Josephs, 1990), it makes sense that thoughts may get stuck in a repetitive cycle, particularly about salient or upsetting material. Other factors such as mood, strength of provocation, or the type of provocation might also influence the amount of state hostile rumination individuals express. We also found that women reported more state hostile rumination than men, although the effect was small. Similar gender differences have not been observed in dispositional hostile rumination, either in our data or in other studies (Stoia-Caraballo et al., 2008; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). Future research is needed to further elucidate the role of these and other contributors to state hostile rumination.

Interestingly, recent research suggests that manipulated state rumination may not interact with alcohol consumption to increase triggered displaced aggression (Denson et al., 2009, 2011). Triggered displaced aggression occurs when a person is provoked but is unwilling or unable to retaliate against the original provocateur and subsequently receives a more minor, annoying provocation (a trigger) from a second person. In such situations, individuals display levels of aggression against the triggering individual that exceed normative tit-for-tat responding (Miller et al., 2003). Two recent triggered displaced aggression experiments (Denson et al., 2009, 2011) manipulated both alcohol consumption and rumination following an initial provocation. Participants were then given the opportunity to aggress against an annoying fictitious opponent. Although participants in both the rumination and alcohol groups exhibited more aggression, neither study found an interaction between rumination and alcohol consumption. It will be important to understand the differences between these findings and our current results. One obvious difference is that our procedure involved direct and immediate aggressive responding, whereas the triggered displaced aggression studies involved a delay for the introduction of another trigger. Perhaps state rumination is most likely to exacerbate intoxicated aggression immediately following a provocation and when the aggression is directed at the original provocateur. Future studies might explore whether state rumination affects immediate displaced aggression and how long state hostile rumination lasts in intoxicated individuals following a provocation.

Our results highlight the potential benefits of targeting rumination in violence prevention and intervention programs. High trait ruminators are more likely to use alcohol to cope with distress (Nolen-Hoeksema and Harrell, 2002). Thus, rumination may foretell not only increased aggression but also heavy drinking, suggesting the need for early intervention. Fortunately, promising treatments for pathological rumination do exist. Rumination-focused cognitive and behavioral therapy (Sezibera et al., 2009; Watkins et al., 2007) teaches clients alternative coping strategies (e.g., disclosure of emotions, concrete and compassionate thinking) and has effectively decreased symptoms of depression (Watkins et al., 2007) and posttraumatic stress (Sezibera et al., 2009). Another promising intervention involves training in mindful-ness, which entails bringing one's full attention into the present moment with an attitude of acceptance (Baer, 2003). This unique way of paying attention contrasts with the uncontrollable mental circles of brooding about past experiences and future possibilities that characterize rumination. People who participate in mindfulness courses show not only decreased rumination (Ramel et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 2008) but also decreased aggression and delinquent behavior (Singh et al., 2007). Given these promising treatments, mental health providers as well as public health researchers might consider the use of rumination-focused interventions to mitigate and possibly prevent alcohol-related violence.

It is important to note some limitations with our measurement of state hostile rumination. First, only 62% of our sample completed this measure. However, these participants did not differ from other study participants on demographics or level of trait rumination, suggesting that the smaller sample for this measure should not affect our conclusions. More importantly, state rumination was technically measured following our dependent variable (the aggression task). We did this because measuring an additional variable during the TAP would have invalidated our measure of aggression. Given that the state rumination questionnaire was administered immediately following the TAP, we assume that these responses are representative of participants' thoughts during the task. However, future studies could develop a methodology that allows state rumination to be measured during provocation and the assessment of aggression. Finally, we do not know whether state hostile rumination reflected mere anger in response to the provocation. Although no previous research has examined the associations between hostile rumination and angry mood, trait angry rumination does share 33% of its variance with dispositional anger (Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). Therefore, we expect that the more anger individuals feel after a provocation, the more they will engage in hostile rumination. However, we do not believe that state hostile rumination and state anger are the same construct. Future research should measure both state mood and rumination to determine unique effects that state hostile rumination has on aggressive behavior.

In conclusion, this research constitutes the first study to demonstrate that heightened trait and state hostile rumination are risk factors for intoxicated aggression. The cognitive neo-associationistic theory about rumination and aggression (Berkowitz, 1993; Miller et al., 2003) in particular emphasizes the role of state rumination in activating aggression-related networks. Our results confirm that it is important to differentiate between state and trait rumination, and that factors other than dispositional rumination may affect how much people ruminate following a provocation. Although much more research is needed to understand the effects of both trait and state hostile rumination on various types of intoxicated aggression, the current study constitutes an important step.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and National Center for Research Resources Grant R01-AA-11691 awarded to Peter R. Giancola.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Selby EA, Joiner TE. Anger rumination across forms of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DS, Taylor SP. Effects of alcohol and aggressive disposition on human physical aggression. Journal of Research in Personality. 1991;25:334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Barber L, Maltby J, Macaskill A. Angry memories and thoughts of revenge: The relationship between forgiveness and anger rumination. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Berger A, Posner MI. Pathologies of brain attentional networks. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM. Income, family characteristics, and physical violence toward children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Towards a general theory of anger and emotional aggression: Implications of the cognitive-neoassociationistic perspective for the analysis of anger and other emotions. In: Wyer RS Jr, Srull TK, editors. Perspectives on anger and emotion. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Barnwell SS, Earleywine M. Alcohol-aggression expectancies and dispositional rumination moderate the effect of alcohol consumption on alcohol-related aggression and hostility. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:327–338. doi: 10.1002/ab.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger and aggressive responding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:724–731. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Bonacci AM, Pedersen WC, Vasquez EA, Miller N. Chewing on it can chew you up: Effects of rumination on triggered displaced aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:969–983. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Cooper HM. Effects of alcohol on human aggression: An integrative research review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:341–354. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV. Indicators of aggression: The Dissipation-Rumination Scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1986;7:763–769. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Gargaro T, Pastorelli C, Prezza M, Renzi P, Zelli A. Individual differences and measures of aggression in laboratory studies. Personality and Individual Differences. 1987;8:885–893. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Paciello M, Gerbino M, Cugini C. Individual differences conducive to aggression and violence: Trajectories and correlates of irritability and hostile rumination through adolescence. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:359–374. doi: 10.1002/ab.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Giancola PR. The relation between alcohol and aggression: An integrated biopsychosocial conceptualization. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17:621–649. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins K, Bell R. Personality and aggression: The Dissipation-Rumination Scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Spanovic M, Aviles FE, Pollock VE, Earleywine M, Miller N. The effects of acute alcohol intoxication and self-focused rumination on triggered displaced aggression. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, White AJ, Warburton WA. Trait displaced aggression and psychopathy differentially moderate the effects of acute alcohol intoxication and rumination on triggered displaced aggression. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:673–681. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem-solving in major depression. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2004;34:1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Drug abuse as a problem of impaired control: Current approaches and findings. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2003;2:179–197. doi: 10.1177/1534582303257007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning: A conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharma-cology. 2000;8:576–597. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Alcohol-related aggression in men and women: The influence of dispositional aggressivity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002a;63:696–708. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Irritability, acute alcohol consumption and aggressive behavior in men and women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002b;68:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. State rumination: Ruminative thoughts about one's opponent in an adversarial laboratory setting. 2007 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Corman MD. Alcohol and aggression: A test of the attention-allocation model. Psychological Science. 2007;18:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Duke AA, Ritz KZ. Alcohol, violence, and the alcohol myopia model: Preliminary findings and implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, Duke AA. Alcohol myopia revisited: Clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:265–278. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Levinson CA, Corman MD, Godlaski AJ, Morris DH, Phillips JP, Holt JC. Men and women, alcohol and aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0016385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Parrott DJ. Further evidence for the validity of the Taylor aggression paradigm. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:214–229. doi: 10.1002/ab.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Saucier DA, Gussler-Burkhardt NL. The effects of affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of trait anger on the alcohol-aggression relation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1944–1954. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000102414.19057.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. An investigation of gender differences in alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:573–579. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlaski AJ, Giancola PR. Executive functioning, irritability, and alcohol-related aggression. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:391–403. doi: 10.1037/a0016582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A, Goodkind MS, Madan A, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Do tests of executive functioning predict ability to downregulate emotions spontaneously and when instructed to suppress? Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;9:144–152. doi: 10.3758/CABN.9.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Miller N, Pollock VE. Alcohol and aggression: A meta-analysis on the moderating effects of inhibitory cues, triggering events, and self-focused attention. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:60–82. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key BL, Campbell TS, Bacon SL, Gerin W. The influence of trait and state rumination on cardiovascular recovery from a negative emotional stressor. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria A. Higher cortical functions in man. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Zehm K. Dysphoric rumination impairs concentration on academic tasks. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers M. “Loss of control” in alcoholism and drug addiction: A neuroscientific interpretation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:225–245. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Sayette MA. Experimental design in alcohol administration research: Limitations and alternatives in the manipulation of dosage-set. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:750–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Pedersen WC, Earleywine M, Pollock VE. A theoretical model of triggered displaced aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:75–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner B. Aspects of human frontal lobe function. In: Jasper HH, Riggio S, Goldman-Rakic PS, editors. Epilepsy and the functional anatomy of the frontal lobe. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AB, Lilienfeld SO. A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:113–136. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA. Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: Tests of gender differences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2002;16:391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RN. Bringing “booze” back in: The relationship between alcohol and homicide. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1995;32:3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Giancola PR. A further examination of the relation between trait anger and alcohol-related aggression: The role of anger control. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:855–864. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128226.92708.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Zeichner A. Effects of alcohol and trait anger on physical aggression in men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:196–204. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JP, Giancola PR. Experimentally induced anxiety attenuates alcohol-related aggression in men. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:43–56. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel W, Goldin PR, Carmona PE, McQuaid JR. The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:433–455. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezibera V, Van Broeck N, Philippot P. Intervening on persistent posttraumatic stress disorder: Rumination-focused cognitive and behavioral therapy in a population of young survivors of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Oman D, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, Flinders T. Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;64:840–862. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Adkins AD, Wahler RG, Sabaawi M, Singh J. Individuals with mental illness can control their aggressive behavior through mindfulness training. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:313–328. doi: 10.1177/0145445506293585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoia-Caraballo R, Rye MS, Pan W, Brown Kirschman KJ, Lutz-Zois C, Lyons AM. Negative affect and anger rumination as mediators between forgiveness and sleep quality. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:478–488. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN. Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP. Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. Journal of Personality. 1967;35:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual aggression: Reciprocal relationships over time in a sample of high-risk women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J. Neurobiology of violence. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins E, Scott J, Wingrove J, Rimes K, Bathurst N, Steiner H, Malliaris Y. Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: A case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2144–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PE, Watson ID, Batt RD. Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects. Updating the Widmark Equation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:547–556. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K, West P. Alcohol-related aggression in the general population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:626–632. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer AJ, Banich MT. Inhibition versus switching deficits in different forms of rumination. Psychological Science. 2007;18:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]