Abstract

Objective:

This study examined how social-influence processes operate during specific drinking contexts as well as the stability and change in these processes throughout the college years.

Method:

Using a measurement-burst design, a hybrid of longitudinal and daily diary methods, we assessed the relationship between event-specific descriptive drinking norms and personal drinking. College students (N = 523) completed a baseline survey followed by a 30-day daily diary each year for up to the 4 study years. The baseline survey assessed participant gender and social anxiety, and the daily survey assessed personal drinking and perceived peer drinking (i.e., event-specific descriptive norms) during social drinking events.

Results:

Multilevel modeling revealed that men's social drinking slightly increased over the 4 years, whereas women's drinking remained steady. Further, on social drinking days when event-specific descriptive norms were high, students drank more, but this relationship was stronger for men than women and did not change over time. However, men's drinking norm perceptions increased across years, whereas women's decreased. Social anxiety did not moderate the relationship between norms and drinking.

Conclusions:

We demonstrate that although gender differences exist in the stability and change of personal drinking, norms, and normative influence on drinking across the years of college, the acute social influence of the norm on personal drinking remains a stable and important predictor of drinking throughout college. Our findings can assist with the identification of how, when, and for whom to target social influence—based interventions aimed at reducing drinking.

College students experience a variety of negative consequences as a result of heavy drinking. For example, each year thousands of college students die in alcohol-related incidents (e.g., traffic accidents, poisoning; Hingson et al., 2009), and hundreds of thousands suffer unintentional self-injuries or are physically and sexually assaulted by other students who have been drinking (Hingson et al., 2005). College drinking has also been associated with academic (e.g., missing class, lower grade point averages), interpersonal (e.g., arguments), and legal problems (Perkins, 2002; Wechsler et al., 2002). As a result, a number of intervention programs designed to reduce heavy drinking among college students have been implemented across college campuses (Larimer and Cronce, 2007). Interventions focused on norm-based social-influence processes are popular because of recent findings showing a strong influence of perceived peer drinking behavior on individual behavior (for a review, see Lewis and Neighbors, 2006). However, many of these interventions have been met with mixed success. For example, social marketing campaigns that aim to correct misperceptions about peer drinking norms via ads, flyers, or other media have been shown to be effective in reducing drinking in some studies (Perkins, 2002) with no evidence of success in others (Clapp et al., 2003; Wechsler et al., 2003). Other social norm approaches, such as personalized normative feedback, show more promise in reducing alcohol use (Lewis and Neighbors, 2006); however, more research is needed to determine how these programs work, for how long, and for whom.

Interventions based on social-influence processes, such as norms, might be enhanced through a more in-depth understanding of how these processes occur in students’ daily lives and how they may change during the college years. There is a scarcity of (a) studies of influence processes occurring during specific drinking events and (b) longitudinal studies on social-influence processes and alcohol use (Baer, 2002; Neighbors et al., 2007c). Understanding how social-influence processes operate during specific drinking contexts and the stability and change in these processes as a person progresses through college can assist with the identification of how, when, and for whom to target interventions aimed at reducing drinking (Baer, 2002).

College students are likely to drink during social gatherings with peers present. Therefore, from an intervention standpoint, it is important to understand how social influences affect drinking during such events because of the acute consequences that may occur as a result of them. Standard interventions may decrease an individual's typical drinking level; however, certain events may nonetheless trigger heavy drinking episodes, placing the student at increased risk for many acute alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., unplanned sex, injuries). Few intervention programs have addressed alcohol consumption during such specific drinking contexts (Neighbors et al., 2007c).

Further, it is possible that event-specific norms and their relationship to alcohol use change across the college years, but little is known about the drinking trajectories of individual students (Del Boca et al., 2004), especially in relation to social norms processes. Understanding whether context-specific influence processes may be stronger at different times during the college career (e.g., early in college vs. later in college) might help in targeting norm-based interventions. We are aware of no studies that examine the potential change or stability in contextual social influences over time. Therefore, in the current study, we examined this using a 4-year longitudinal design paired with a daily diary method to get a broader picture of developmental trends in the alcohol-norm and drinking relationship during specific social drinking events.

Social influence and alcohol use

The focus theory of normative conduct (Cialdini et al., 1990) is useful in describing how alcohol norms may affect drinking behavior. According to this theory, there are two types of norms: descriptive (what most people do) and injunctive (what ought to be done). We concentrate on the former. Descriptive norms indicate what is typical or normal in a particular setting and guide behavior by providing information about what is effective and adaptive. Focus theory further posits that such norms should only guide behavior when they are salient or “in focus,” via either situational or dispositional factors, and that such norms are most influential when expressed in the same or closely matching situations (Goldstein et al., 2008; Kallgren et al., 2000). Therefore, proximal reference groups (peers in the immediate surrounding) may be more important than more distant ones (typical college students at the university).

Peer drinking behavior can subtly influence personal consumption by informing people about what is typical and socially accepted in a given social setting (Borsari and Carey, 2001). Perceived social norms regarding drinking have been shown to be some of the best predictors of alcohol consumption among college students when compared with other common factors related to alcohol use such as demographics, motives, affect, and expectancies (Neighbors et al., 2007b). The more a student perceives important others as drinking heavily or as approving of heavy alcohol use, the higher his or her personal alcohol consumption (Borsari and Carey, 2001). Studies suggest that college students overestimate the average student's positive attitudes toward heavy alcohol use and feel that their own beliefs regarding alcohol are less permissive (Prentice and Miller, 1993). Students are likely incorrectly inferring that others have a high degree of comfort and ease with alcohol from their outward behavior. Although this may not accurately reflect their private attitudes toward drinking, outward displays by peers may guide individual drinking behavior (Prentice and Miller, 1993). In addition, the norms of more proximal reference groups tend to have the greatest influence on personal drinking (Cho, 2006; Goldstein et al., 2008; LaBrie et al., 2009). For example, close friends have been found to have more of an influence on drinking than less salient groups such as the “typical college student” (Cho, 2006).

Individual differences

There may be important individual differences that affect the social influence-drinking relationship. In this study, we concentrate on two individual differences: gender and social anxiety. One possibility is that the effect of norms on drinking might be stronger among men. Men perceive more permissive alcohol norms than do women (Borsari and Carey, 2001) and might be more susceptible to normative pressure because they feel more social pressure to drink and feel subjected to social embarrassment and negative social consequences if they voice concerns about drinking (Suls and Green, 2003). Further, men and women differ in the magnitude of and reaction to discrepancies between perceived norms and personal drinking attitudes, such that women's discrepancy is greater, but men shift their attitudes over time in the direction of what they believe the norm is, whereas women's attitudes remain more stable (Borsari and Carey, 2003; Prentice and Miller, 1993).

Social anxiety may also modify the social influence-drinking relationship. Socially anxious individuals fear negative evaluation by their peers during social interactions (Leary et al., 1988). Therefore, to avoid being evaluated negatively, they may focus more on peer behavior and be more susceptible to norms than those low in social anxiety. Neighbors et al. (2007a) and LaBrie et al. (2008) found that the relationship between perceived norms and drinking was stronger among students who were higher in social anxiety, especially men. This is in line with focus theory, which suggests that dispositional factors may affect norm focus (Kallgren et al., 2000).

Longitudinal studies on social influence and alcohol use

Only a few studies have used longitudinal methods to study social-influence processes and college drinking. Some findings suggest a general decline in perceived drinking norms over time (Baer, 1994; Parra et al., 2007). This suggests that norm perceptions would be the highest early in college and that perhaps social influence-related heavy drinking and associated problems may occur earlier in college, rather than later. However, whether there is a relationship between norm perception and drinking over time is unclear. Some studies show no such relationship (Capone et al., 2007), whereas others do find a modest effect of norms on drinking (Cullum et al., 2010; Reifman et al., 2006). Although it has provided important insight, the longitudinal social norms research to date has two types of limitations. First, most of these studies used relatively short follow-up periods of a month or two (Neighbors et al., 2006; Prentice and Miller, 1993, Study 3), with nearly all remaining studies focusing on normative social influence over the course of the first or second year of college (Baer, 1994; Capone et al., 2007; Reifman et al., 2006) rather than over a period more representative of the typical college career (i.e., 4 years).

A second limitation in these longitudinal studies is that, within each wave of data collection, they examine abstractions of general or typical social norms and personal drinking behavior over a period of time (e.g., the last month, 3 months, year) that may not adequately capture acute social-influence dynamics as they occur during specific social drinking events. Thus, when these longitudinal designs examine cross-wave social influences, they only assess cross-wave changes in general drinking behavior and the degree to which these changes may be attributable to past perceptions of general, context-independent social drinking norms. Individuals’ drinking levels may vary widely across drinking events within each wave, and the risks associated with heavy drinking are often specific to acute instances of drinking (Neighbors et al., 2007c; Weitzman et al., 2003). As such, some important research questions remain unaddressed by past longitudinal studies on social influence and drinking.

Current study

Traditional social norms studies emphasize macro-level abstractions in typical alcohol use. Although important, these studies tell us little about the effect of context on variations in students’ drinking behaviors from their typical patterns or about how contextual social influences on drinking behavior change or remain stable over time. To date, it appears that social-influence processes have not been examined using a more microlevel approach. Whereas other researchers have started to investigate social-influence processes during discrete drinking events or specific contexts that are typical for heavy drinking (e.g., Pedersen and LaBrie, 2008), to date such studies have been entirely cross-sectional. Therefore, the objective of this study was to add to the literature on alcohol and social norms by focusing on microlevel processes rather than macrolevel processes as well as using longitudinal rather than cross-sectional methods. Our specific study goals were (a) to examine the within-person associations between event-specific norms and personal drinking behavior during discrete drinking episodes and (b) to examine how this microlevel, within-person social-influence process varies across person-level factors (i.e., gender and social anxiety) as well as over time. To do this we used a measurement-burst design (Sliwinski, 2008), which is a hybrid of a traditional longitudinal design (e.g., data collected once per year for several years) and a daily diary design (e.g., data collected once per day for several weeks). Measurement-burst designs examine unique processes that may not be captured by traditional daily diary and longitudinal designs. For example, by obtaining several bursts of intensive measurements over time, within-person relationships can be modeled within each burst, in addition to modeling change in both average levels of variables and within-person relationships across bursts (Sliwinski, 2008). In the current study, we assessed the relationship between event-specific drinking norms and personal drinking across four waves of 30-day diary reporting, with a 1-year period between each wave.

We first examined daily social drinking as an outcome. We hypothesized that when the event-specific norm is stronger than what students typically encounter, they will drink more alcohol. Further, we hypothesized that this relationship will be stronger (a) among men compared with women and (b) for students with high social anxiety compared with those low in social anxiety. We made no specific hypothesis regarding change in these associations over time because there are mixed findings regarding whether the relationship between social norms and drinking varies across years (cf. Capone et al., 2007, and Cullum et al., 2010), and no past research of which we are aware has examined whether the relationship between context-specific norms and drinking changes or remains stable across time.

We also examined event-specific norms as an outcome to determine whether they varied across year, gender, and level of social anxiety. We hypothesized that stronger perceived drinking norms would be evident among (a) men compared with women and (b) students high in social anxiety compared with those low in social anxiety. We also examined how these relationships varied by year with no specific predictions for the same reasons stated above.

Method

Participants

Participants were 574 college students (50% male) recruited from an introductory psychology subject pool at a large public northeastern university. At the beginning of the study, participants were mainly White (86%) and had a mean age of 18.77 years (SD = 1.08), with most being freshmen (57%) or sophomore students (34%). Participants were excluded if they did not participate in any of the 4 years of the daily diary phase or completed less than 15 days of the diary data during all 4 of the years (34 excluded), did not report any alcohol use during the diary periods over all 4 years (13 more excluded), or had incomplete data from the initial assessment (3 more excluded). Only data from years when participants were in college were analyzed, resulting in one additional participant being excluded. These exclusions left the final sample at 523, of whom 59% provided 4 years of diary data, 18% provided 3 years, 12% provided 2 years, and 11% provided 1 year. This final sample included participants who had at least 1 year of acceptable daily data, with most having all 4 years; therefore, participants were excluded only if they had no diary data from any year or completed fewer than 15 days of diary data each year. We used all available waves of data that met the minimum criteria (completing at least 15 daily diaries per year) rather than completely excluding participants with any missing data because this is consistent with recommendations for estimating effects using maximum likelihood estimation and provides a more complete picture of the results (Singer and Willet, 2003). There were no differences between the excluded participants and the final sample in age, social anxiety, average daily drinking, class year, full- or part-time status, or ethnicity. The two groups did differ on gender, χ2(1) = 4.73, p = .03, such that the excluded group had more men (65%) than women. This research was conducted with permission from the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

As part of a larger longitudinal study of daily experiences and health, participants completed a baseline survey followed by a 30-day daily diary each year for up to the 4 study years. Both surveys were completed on a secure website. Participants completed the baseline survey and then approximately 2 weeks later began completing the daily portion of the study, which took about 5 minutes to complete. Each year, data were collected approximately 1 month into the start of the semester, with half of the sample completing the diary every fall semester and half every spring semester. Participants completed the diary during the same semester each year. They completed the daily survey between 2:30 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. each day to reduce variation in reporting times and to coincide with the end of the school day. Participants received course credit and a monetary incentive for participating in the study. Participants complied with the daily diary protocol at acceptable levels each year. Of the possible diary days participants could have completed (i.e., each participant had 30 potential diary days per year) each year, they completed 84%, 83%, 86%, and 84% during Years 1 through 4, respectively.

Measures

Baseline survey.

During the baseline assessment each year, in addition to demographic questions, participants completed the social anxiety subscale of the Self-Consciousness Scale (Fenigstein et al., 1975). This scale measures the extent to which participants are fearful of being evaluated by others and contains six items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree (e.g., “It takes me time to overcome my shyness in new situations”). Scores were summed (Cronbach's α = .82) and ranged from 8 to 41 (M = 23.28, SD = 6.30). The social anxiety scores varied very little from year to year and additional analyses determined that yearly variation in these scores did not predict the outcome variables; therefore, the social anxiety scores from Year 1 were used in all analyses.

Daily survey.

Each day, participants were asked if they were with other people who were drinking last night (yes or no). We measured event-specific descriptive norms by asking participants on days they answered “yes” to the above question to report the average number of alcoholic drinks others had during social drinking events the previous night. For personal drinking, they also reported the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed the previous night. Response options for both of these questions ranged from 0 to greater than 15 (coded 16). In addition, participants reported the number of hours they spent interacting with friends or acquaintances the previous night (0 to >12) and the number of drinks they accepted from other people the previous night (0 to >15). Each day, participants received the following definition of a serving of alcohol: one 12-oz. can or bottle of beer, one 5-oz. glass of wine, one 12-oz. wine cooler, or 1.5 oz. of distilled spirits (Wechsler and Nelson, 2001).

Statistical analysis

We used multilevel modeling to estimate three-level models (drinking days nested within years nested within people) with Hierarchical Linear Modeling software (Version 6.06; Raudenbush et al., 2008). Two models were estimated, the first with number of drinks as the outcome and the second with the event-specific norm as the outcome. In all analyses, Level 1 variables were person-mean centered. To model linear change over the 4 years, the Year variable was entered at Level 2 and was coded such that zero represented Year 1 (Singer and Willet, 2003). We modeled Year as a linear growth term after determining in additional analyses that adding quadratic and cubic growth terms at Level 2 did not improve model fit or add to the predictive value of the model. Further, it should be noted that the year variable refers to “year in the study” rather than “year in school.” To determine whether year in school affected the pattern of results, additional analyses were conducted with year in school at the beginning of the study entered as a control variable at Level 3, and the pattern of results did not change. At Level 3, social anxiety was grand mean-centered and gender was dummy coded (1 = men, 0 = women). To control for weekly cycles in drinking (i.e., more drinking occurs on weekends), six dummy-coded variables with Sunday coded 0 and all other days coded 1 were included in the Level 1 portion of the model. We also included time spent interacting with others as a control variable at Level 1 because drinking has been found to be positively related with social interaction (Weitzman et al., 2003).

Results

Daily descriptive statistics

Of all completed days across all waves of the study (44,095), participants reported interacting with others who were drinking on 26% of them, for a sum of 11,464 observations of social drinking events (per person M = 19.8, SD = 13.3). These observations of social drinking events include 72% of the total days in which participants drank and 7% of the total days in which participants reported not drinking. On social drinking days (i.e., days others were drinking), participants had a mean of 5.75 (SD = 3.90) drinks and reported that others had 5.80 (SD = 3.34) drinks on average.

We examined the proportion of the total variation in norms and drinking at each of the three levels of analysis by calculating intraclass correlations. Within-person differences (Level 1) accounted for a considerable portion of the variance for both norms and drinking (66% and 81%, respectively), year differences (Level 2) accounted for the least (10% and 2%, respectively), and between-person differences (Level 3) accounted for the remaining variance (24% and 17%, respectively).

Drinking multilevel model results

We examined alcohol use during social drinking episodes as a function of event-specific norms (Level 1) and year (Level 2), as well as gender and social anxiety (Level 3). Two- and three-way interactions among these variables were also examined. For this model, the number of drinking offers accepted from others was included as an additional control variable at Level 1 because we were interested in passive social influences (i.e., event-specific norms) on drinking rather than active influences in the form of drinking offers from peers. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multilevel model results for drinking as a function of event-specific norm, social anxiety, year, and gender

| Variable | Unstandarized coefficient b(SE) | t | p |

| Gender dummy | 1.77(0.26) | 6.85 | <.001 |

| Year | 0.11 (0.08) | 1.35 | .179 |

| Social anxiety | -0.02 (0.02) | -0.94 | .350 |

| Norm | 0.37 (0.03) | 10.68 | <.001 |

| Time spent interacting | 0.20 (0.01) | 5.45 | <.001 |

| Offers accepted | 0.55 (0.02) | 34.86 | <.001 |

| Year × Gender | 0.24(0.12) | 2.04 | .042 |

| Year × Social Anxiety | -0.001 (0.01) | -0.11 | .915 |

| Year × Norm | 0.02 (0.02) | 1.23 | .225 |

| Norm × Social Anxiety | -0.01 (0.01) | -1.29 | .198 |

| Norm × Gender | 0.12 (0.05) | 2.72 | .007 |

| Social Anxiety × Year × Norm | -0.01 (0.00) | -0.44 | .657 |

| Norm × Gender × Year | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.48 | .635 |

Notes: Includes only days in which participants drank with others (e.g., social drinking days). Day of week was also included as a control variable (six dummy-coded variables, with Sunday as the reference). Level 1 variables were person-mean centered, Year was centered at Year 1 (i.e., Year 1 = 0), Social anxiety was grand-mean centered, and Gender was dummy-coded (Men = 1, Women = 0).

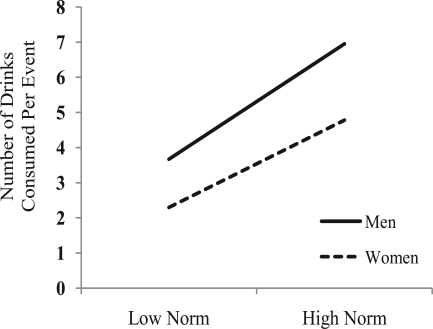

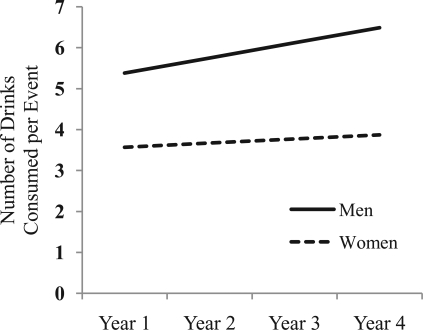

Gender and event-specific norms were significant predictors of drinking; however, these effects were qualified by a significant two-way interaction between them. As depicted in Figure 1, for both men and women, event-specific norms had a positive relationship with drinking, such that on days when the event-specific norms were relatively higher than the average, more alcohol was consumed. Although the interaction indicates that the association was stronger for men as predicted, follow-up simple slopes tests indicated that the relationship was significant for both men (b = 0.49, p < .001) and women (b = 0.36,p < .001). There was also a significant two-way interaction between study year and gender (Figure 2) such that men's social drinking increased from Year 1 to Year 4 (b = 0.38, p < .001), whereas women's social drinking remained relatively stable over time (b = 0.07, p = .40) as revealed by simple slopes tests.

Figure 1.

gender Number of drinks as a function of event-specific norm and

Figure 2.

Number of drinks as a function of gender and year

Norms multilevel model results

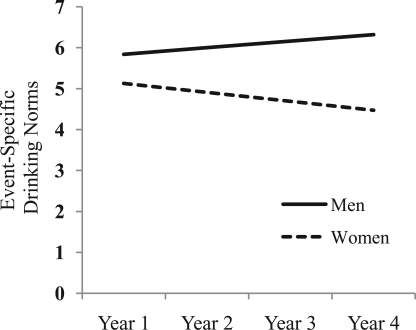

To examine whether event-specific drinking norm perceptions changed over time in college and how individual differences in gender and social anxiety were related to this process, we estimated a model with event-specific norms as the outcome. As in the previous model, year was entered at Level 2 and gender and social anxiety were entered at Level 3. We also tested for two cross-level interactions: Year × Gender and Year × Social Anxiety. In this model, number of personal drinks was entered as a control variable at Level 1 to partial out the potential effect of participants’ own drinking on their norm perceptions. As shown in Table 2, gender and year were significant predictors of event-specific norms; however, these effects were qualified by a significant interaction between the two. This interaction is depicted in Figure 3. Follow-up simple slopes tests indicated that men's event-specific drinking norms increased from Year 1 to Year 4 (b = 0.15, p = .02), whereas women's decreased (b = -0.22, p < .001).

Table 2.

Multilevel model results for event-specific norms as a function of social anxiety, year, and gender

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficient b(SE) | t | P |

| Gender dummy | 0.71 (0.19) | 3.67 | <.001 |

| Year | -0.22 (0.06) | -3.58 | .001 |

| Social anxiety | -0.03 (0.02) | -1.88 | .060 |

| Time spent interacting | 0.09 (0.01) | 10.05 | <.001 |

| Evening drinks | 0.48 (0.01) | 67.83 | <.001 |

| Year x Gender | 0.38 (0.09) | 4.24 | <.001 |

| Year x Social Anxiety | -0.00 (0.01) | -0.12 | .862 |

Notes: Includes only days in which participants drank with others (e.g., social drinking days). Day of week was also included as a control variable (six dummy-coded variables, with Sunday as the reference). Level 1 variables were person-mean centered, Year was centered at Year 1 (i.e., Year 1 = 0), and Gender was dummy-coded (men = 1, women = 0).

Figure 3.

Event-specific norms as a function of gender and year

Discussion

Using a measurement-burst design, we examined the relationship between event-specific descriptive drinking norms and alcohol use among college students and investigated potential individual and year differences in this relationship. We found that men's social drinking slightly increased over the 4 years, whereas women's drinking remained steady. This is consistent with other longitudinal studies suggesting that drinking frequency and quantity slightly or marginally increase over the 4 years of college (Baer et al., 2001).

Further, we found that on days when event-specific descriptive drinking norms were higher than what students typically encountered, they drank more, but that this relationship was stronger for men than women. This is consistent with the focus theory of normative conduct (Cialdini et al., 1990), which suggests that the influence of descriptive norms is context-specific and is likely to guide behavior when norms are likely to be focal, such as during social gatherings where others are drinking. The stronger effect for men is consistent with past findings (Borsari and Carey, 2001; Prentice and Miller, 1993, Study 3) and the notion that they might anticipate greater negative consequences if they do not drink or if they voice concerns about drinking (Suls and Green, 2003). An alternative explanation is that alcohol is more central to men's social lives than women's, and men may be more visible in the drinking environment (Borsari and Carey, 2003). Men may feel more pressure to learn to be comfortable with alcohol, and women may interpret alcohol norms as less relevant to their behavior, making them more comfortable with being slightly at odds with the norm (Prentice and Miller, 1993). Most research examining alcohol norms and drinking behavior is cross-sectional or macrolongitudinal; therefore, these findings add to the literature by showing that norms operate at the event level in addition to the more global level that has been shown in previous work. Further, the event-specific norm and drinking relationship did not change over time, indicating the stability in this social-influence process during the college years.

We also investigated whether event-specific descriptive norm perceptions differed over the 4 years and between men and women. Men's drinking norm perceptions increased across years, whereas women's perceptions decreased, supporting previous literature suggesting that men perceive more permissive alcohol norms than women (Borsari and Carey, 2001; Capone et al., 2007). This could partially explain why men's drinking increased over the college years and women's drinking remained steady. Men's perception of event-specific norms may increase over the college years, whereas women's decrease because perhaps the gender composition of drinking groups change for men and women over time. For example, as women mature they may be more likely to drink with other women rather than mixed-gender groups. It is also possible that, along with composition changes, same-gender peer drinking becomes more salient over time. Indeed, it has been found that same-sex peer norms have a greater influence on drinking behavior than opposite-sex peers (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004; Thombs et al., 2005). Therefore, men may be attending to the norms of their male peers, whereas women are attending to those of their female peers, and this may become stronger over time. Also, as mentioned above, alcohol may become more salient in men's social lives over time, whereas it becomes less salient for women, leading to perceptions of heavier drinking norms over time for men and weaker perceptions for women. However, these explanations are only speculation; future research will need to assess gender-specific norm perceptions as well as gender composition of groups to support these suggestions.

Social anxiety did not moderate the relationship between norms and drinking, contrary to our predictions derived from focus theory. Therefore, social anxiety does not seem to have a proximal effect on the norm-drinking relationship in that people with high social anxiety do not more strongly attend to immediate drinking norms once they are in a drinking situation. However, it is possible that a different process may be at work in that norms may still drive drinking-related behavior, as has been found in previous cross-sectional work (LaBrie et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2007a). For example, people with high social anxiety might be more influenced by norms to go to settings where drinking is common (e.g., a party) to try to fit in. Once in that situation, however, their drinking contingencies are no different from others. It is also possible that the proposed relationship between social anxiety, daily drinking, and norms would have been evident among those with strong expectancies that drinking facilitates social interactions (Gilles et al., 2006). Thus, future research should include measures regarding selection into drinking situations as well as expectancies during social situations to further examine these possibilities.

Implications and future directions

This study has implications for research and interventions aimed at college student alcohol use. For example, although several short-term longitudinal studies have indicated that normative perceptions do not change or grow weaker over time (Baer, 1994; Capone et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2006), this study suggests that this pattern may only be true for women over the entire course of college. Previous longitudinal studies in this area have mainly focused on the first year of college; therefore, they may not have captured the increasing perceptions that this study found for men given the longer follow-up period. This indicates a need for more research on why there are gender differences in normative perceptions over time, as well as additional longitudinal research covering more than the first year of college. For example, future research could examine whether there are gender differences in perceived negative social consequences regarding not drinking either at the daily level or the individual difference level and whether such perceived consequences change over time.

From an intervention standpoint, this study can assist in determining how, when, and for whom interventions may be more effective. As far as timing and targeted population, this study suggests that it may be important to target men not only in their early college years before their drinking and norm perception becomes stronger but also later when their normative perceptions and drinking are high. Further, because we found important gender differences in this study, gender may need to be taken into account in how interventions are implemented. For example, social norm-based interventions using individualized feedback have been found to be somewhat effective and could be used to address the norm-drinking contingencies found in this study. However, such interventions have been found to be less effective for women, perhaps because gender nonspecific feedback is used (e.g., the typical student) and may cause women to think about men's drinking. This suggests the need to use gender-specific feedback in such programming (Lewis and Neighbors, 2006). Indeed, our study may provide preliminary support to the notion that gender-specific feedback should be used given the differences in normative perceptions and drinking we found between men and women. Future research should include measures of gender-specific norm perceptions to provide more clear support for the use of gender-specific feedback in programming.

Limitations

Although this study used a unique method to investigate social-influence processes in alcohol use among college students and uncovered gender differences in changes in norms over year in school, there are some limitations. For the event-specific norm measure, participants were asked to average the number of drinks across all “others” they were with during each social drinking event. Although this daily measurement is a potential improvement over cross-sectional methods of determining normative perceptions, participants may have had difficulty in estimating this average. However, this criticism can be used for any norm perception assessment. Additionally, because the term “others” was used, it is possible that on some occasions participants were not reporting specifically on peers because others in the environment could have included nonpeers (e.g., parents). Along these lines, we did not assess gender-specific norm perceptions; therefore, if more than one gender was present in the drinking setting, participants essentially had to average drinking for men and women, which may have been difficult. It is also possible that participants attended to and reported more often on same-gender peers. More specific language (e.g., female peers, male peers) should be used in future investigations of norm perceptions to address these issues. Further, we did not obtain information about the gender composition of the groups that participants were with each night or the specific drinking settings (e.g., bar, party), which may moderate both the level of the drinking norm and the degree to which the norm generalized to the participant in each setting. Future research should assess whether the gender makeup of others in drinking situations and the drinking setting moderate the effect of their perceived drinking level on personal consumption. Also, in this study we analyzed data only for days on which participants were with other people who were drinking and excluded drinking occasions during which others were not drinking. Such occasions, however, comprised only 4% of the days. Thus, our findings pertain to the overwhelming majority of drinking episodes for college students. Finally, there was some attrition during the study; however, the majority of students provided all 4 years of data.

Conclusions

Whereas theories of descriptive social norms suggest that norms will be most influential during the immediate situation (Cialdini et al., 1990; Reno et al., 1993), little research on drinking has investigated the effect of event-specific drinking norms present while students are attending social drinking events or examined how drinking, norms, and the influence of norms on drinking change across years in college. Our findings indicate that although gender differences exist in the change of personal drinking, norms, and normative influence on drinking across the years of college, the acute social influence of the norm on personal drinking remains a stable and important predictor of students’ drinking throughout the duration of the typical college career for both men and women. Intervention and research efforts that try to curb heavy drinking or to reduce the harms and risks that it entails for students might be more effective if they took context-specific social-influence processes into account.

Footnotes

Funding for this study was provided by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32-AA007290 and P50-AA03510.

References

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy-drinking college students: 4-year follow-up and natural history. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Wood MD, Borsari B, Laird RD. Fraternity and sorority involvement, social influences, and alcohol use among college students: A prospective examination. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:316–327. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. Influences of norm proximity and norm types on binge and non-binge drinkers: Examining the under-examined aspects of social norms interventions on college campuses. Journal of Substance Use. 2006;11:417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Lange JE, Russell C, Shillington A, Voas RB. A failed norms social marketing campaign. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:409–414. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum J, Armeli S, Tennen H. Drinking norm-behavior association over time using retrospective and daily measures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:769–777. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles DM, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and self-efficacy as predictors of heavy drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB, Griskevicius V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35:472–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallgren CA, Reno RR, Cialdini RB. A focus theory of normative conduct: When norms do and do not affect behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1002–1012. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C. Self-consciousness moderates the relationship between perceived norms and drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Cail J, Hummer JF, Lac A, Neighbors C. What men want: The role of reflective opposite-sex normative preferences in alcohol use among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:157–162. doi: 10.1037/a0013993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Campbell CD. Self-presentational concerns and social anxiety: The role of generalized impression expectancies. Journal of Research in Personality. 1988;22:308–321. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: a review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Fossos N, Woods BA, Fabiano P, Sledge M, Frost D. Social anxiety as a moderator of the relationship between perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007a;68:91–96. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007b;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walters ST, Lee CM, Vader AM, Vehige T, Szigethy T, DeJong W. Event-specific prevention: Addressing college student drinking during known windows of risk. Addictive Behaviors. 2007c;32:2667–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra GR, Krull JL, Sher KJ, Jackson KM. Frequency of heavy drinking and perceived peer alcohol involvement: Comparison of influence and selection mechanisms from a developmental perspective. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2211–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. Normative misperceptions of drinking among college students: a look at the specific contexts of prepartying and drinking games. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:406–411. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon RT. HLM Version 6.34g. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Watson WK, McCourt A. Social networks and college drinking: Probing processes of social influence and selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:820–832. doi: 10.1177/0146167206286219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno RR, Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA. The transsituational influence of social norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ. Measurement-burst designs for social health research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Green P. Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psychology. 2003;22:479–486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Ray-Tomasek J, Osborn CJ, Olds RS. The role of sex-specific normative beliefs in undergraduate alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2005;29:342–351. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993—2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: What's five drinks? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:287–291. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF, Lee JE, Seibring M, Lewis C, Keeling RP. Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:484–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Nelson TF, Wechsler H. Taking up binge drinking in college: The influences of person, social group, and environment. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32:26–35. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]