Abstract

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) poses one of the great therapeutic challenges in oncology. RCC is predominantly refractory to treatment with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, and until recently management options were limited to immunotherapy or palliative care. However, in the past few years we have experienced a sea change in the treatment of advanced RCC with the introduction of targeted therapies that derive their efficacy at least in part through alterations in tumor angiogenesis. The tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib, pazopanib, and sorafenib, the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab (in combination with interferon-α), and the rapamycin analogs, temsirolimus and everolimus, are now approved agents in the United States for the treatment of metastatic RCC. Efforts to expand upon these successes include developing novel antiangiogenic agents, optimizing concomitant and sequential regimens, identifying predictors of response to specific treatments, and further dissecting the underlying molecular pathogenesis of RCC to reveal novel therapeutic targets.

Keywords: carcinoma, renal cell, therapeutics

Introduction

More than 54,000 new cases of cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis, and over 13,000 deaths related to kidney cancer, were estimated to occur in the United States in 2009 [Jemal et al. 2009]. While nephrectomy is the preferred treatment option for local disease, approximately 30% of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) present with metastatic disease, and about one-third of patients with localized disease relapse following nephrectomy [Golshayan et al. 2008]. Cytotoxic chemotherapy is not effective in the treatment of metastatic RCC, with response rates of less than 5% and no impact on overall survival (OS) when compared with placebo or supportive care [Coppin et al. 2008; Cohen and Mcgovern, 2005]. For years, immune modulating therapy was the principal treatment option for patients with metastatic RCC. High-dose aldesleukin (interleukin-2 [IL-2]) was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced RCC based on the results of phase II studies in which 7% of patients achieved durable complete responses (CRs) lasting greater than 10 years [Mcdermott and Atkins, 2006; Fyfe et al. 1995]. Patients treated with high-dose IL-2 are at risk for capillary leak syndrome and hypotension that can require intensive care-level intervention. Interferon-α (IFN-α) immunotherapy is also used in the treatment of metastatic disease. IFN-α was shown to improve survival compared with medroxyprogesterone acetate or vinblastine, but IFN-based regimens are also associated with low response rates [Rini et al. 2009a]. Furthermore, only a limited subset of patients appears to sustain benefit from immunotherapy. For example, IL-2 and IFN treatment, individually or in combination, was not associated with improved progression-free survival (PFS) or OS when compared with medroxyprogesterone acetate for patients with intermediate prognosis metastatic RCC [Negrier et al. 2007].

High-dose IL-2 may continue to offer the best chance for achieving a durable CR for a highly select group of patients with favorable-prognosis metastatic disease. However, the significant associated toxicities and low overall response rate (ORR) necessitated investigation into novel therapies. Recent advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of RCC, particularly the unique relationship between RCC and angiogenesis, enabled the development of targeted therapies that comprise the current standard of care. Starting in December 2005 and up until this date, the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sunitinib, pazopanib, and sorafenib, as well as the rapamycin analogs, temsirolimus and everolimus, have been approved for use in the United States in the treatment of metastatic RCC. In addition, the combination of the antivascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody bevacizumab with IFN-α has been approved for use in Europe. In this article, we briefly discuss the biological rationale that promoted the generation of these agents and in this context discuss novel targeted therapies that may provide improved efficacy or diminished toxicity. We also discuss efforts to validate and expand upon existing prognostic factors for RCC in the age of targeted therapies. We limit our discussion to the treatment of clear cell RCC. For a review of advances in the treatment of non-clear cell renal cancer, we refer the reader to the recent article by Heng and Choueiri [Heng and Choueiri, 2009].

The biological basis for current targeted therapies in RCC

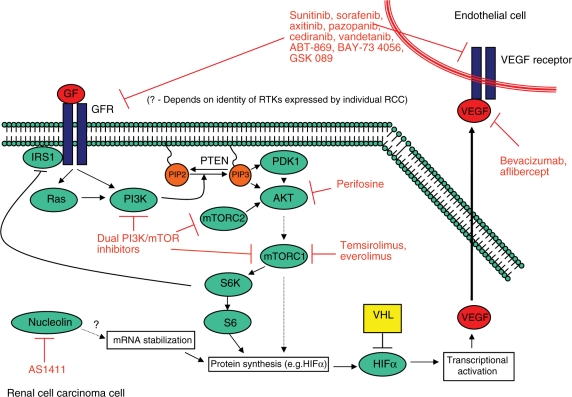

Conventional or clear cell RCC is the most common histologic subtype of kidney cancer, accounting for about 80% of cases [Golshayan et al. 2008]. The von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene is silenced in most cases of sporadic RCC [Kaelin, 2004]. VHL encodes a protein, pVHL, which is a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase for hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIFα) proteins that targets HIFα for degradation by the proteasome under conditions of normal oxygen tension. Under hypoxic conditions, or if VHL is silenced by mutation or methylation, HIFα proteins heterodimerize with HIFβ to act as transcription factors for multiple hypoxia-inducible genes involved in proliferation, angiogenesis, and metabolism, including VEGF, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), and many others [Kaelin, 2004]. As shown in Figure 1, several targeted therapeutics for metastatic RCC disrupt signaling via HIF targets or upstream regulators of HIF expression to inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis.

Figure 1.

Therapeutic targets in renal cell carcinoma. AKT, serine/threonine protein kinase; GF, growth factor; GFR, growth factor receptor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP, phosphatidylinositol phosphate; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VHL, von Hippel–Landau. Modified with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media from Figure 1 [Courtney and Choueiri, 2009].

Current targeted therapies in RCC

Sorafenib tosylate and sunitinib malate inhibit multiple tyrosine kinases expressed on RCC tumor cells or on endothelial cells that relay proliferative or angiogenic signals. Sorafenib blocks receptors for VEGF and PDGF (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGFR-β), as well as the tyrosine kinases Flt3 and c-Kit [Hutson and Figlin, 2007; Strumberg et al. 2005]. It also inhibits the serine/threonine kinase c-Raf and B-Raf. Sorafenib received FDA approval in 2005 for use in advanced RCC based on the results of a phase III trial that demonstrated improved median PFS for patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic RCC treated with sorafenib compared to patients in the placebo arm (5.5 versus 2.8 months, p = 0.000001) [Escudier et al. 2005, 2007a, 2009a]. However, sorafenib failed to demonstrate an improvement in PFS compared with IFN in a randomized phase II study of treatment-naïve patients with metastatic RCC [Rini et al. 2009a; Szczylik et al. 2007].

Sunitinib is a polykinase inhibitor with efficacy against VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, Flt3, and c-Kit [Hutson and Figlin, 2007]. Phase II trials showed significant response rates in patients with metastatic RCC previously treated with cytokine therapy (IFN or IL-2), leading to FDA approval in January 2006 [Motzer et al. 2006a, b]. A subsequent phase III study demonstrated a significant improvement in PFS (11 versus 5 months, p < 0.001) and an improvement in OS (26.4 versus 21.8 months, p = 0.051) associated with sunitinib treatment when compared with IFN-α and established sunitinib as a ‘reference standard’ first-line treatment option for patients with metastatic RCC [Figlin et al. 2008; Motzer et al. 2007].

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase and central component of signaling pathways that govern cell proliferation, survival, metabolism, angiogenesis, and apoptosis (Figure 1). Temsirolimus and everolimus are allosteric inhibitors of the mTOR/Raptor complex known as mTORC1 [Le Tourneau et al. 2008]. Temsirolimus received FDA approval in 2007 and is considered first-line treatment for patients with high-risk, metastatic RCC, based on results from a phase III randomized trial comparing treatment with temsirolimus, IFN-α, or a combination of temsirolimus and IFN-α [Hudes et al. 2007]. OS was significantly improved for patients treated with temsirolimus (10.9 months) compared with those treated with IFN-α (7.3 months, hazard ratio [HR] 0.73, p < 0.008) [Hudes et al. 2007]. The combination of temsirolimus and IFN-α did not lead to a significant change in overall survival (8.4 months) compared with IFN-α alone, perhaps due to the increased number of serious adverse events (AEs), or the decreased dose of temsirolimus administered in the combination arm [Hudes et al. 2007]. Everolimus received FDA approval in 2009 for the treatment of patients with metastatic RCC following previous antiangiogenic therapy with sorafenib or sunitinib therapy. In a randomized phase III study (RECORD-1) involving patients whose cancer had progressed through treatment with sunitinib, sorafenib, or both, treatment with everolimus was associated with an improvement in median PFS (4.0 months, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.7–5.5) compared to treatment with placebo (1.9 months, 95% CI 1.8–1.9) [Motzer et al. 2008]. Following unblinding at the second interim analysis, patients receiving placebo were crossed over to the everolimus treatment arm [Kay et al. 2009]. Updated results for RECORD-1 presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2009 Genitourinary Cancers (GU) Symposium revealed a 4.9-month median PFS (CI 4.0–5.5) for patients treated with everolimus compared with 1.9 months (CI 1.8–1.9) for patients who received placebo [Kay et al. 2009]. OS data were not mature.

Two phase III trials have demonstrated the efficacy of adding the recombinant anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab to IFN-α. CALGB 90206 randomized previously untreated patients to receive bevacizumab and subcutaneous IFN or IFN alone. Treatment with the combination arm was associated with an increased PFS (8.5 versus 5.2 months, p < 0.0001) and ORR (25.5% versus 13.1%, p < 0.0001) [Rini et al. 2008]. The median OS for patients treated with bevacizumab plus IFN-α was 18.3 months (95% CI; 16.5–22.5), compared with 17.4 months (95% CI; 14.4–20.0) for patients who received IFN-α alone, but this result did not meet criteria for statistical significance [Rini et al. 2009b]. Similarly, an international trial (AVOREN) comparing treatment with the combination of IFN-α-2a and bevacizumab to IFN-α-2a plus placebo demonstrated an improved PFS with the addition of bevacizumab (10.2 versus 5.4 months, p < 0.0001) [Escudier et al. 2007b]. There was a trend toward improved median OS for patients treated with bevacizumab plus IFN (23.3 months) compared with patients who received placebo with IFN (21.3 months) (HR 0.86 [95% CI: 0.72–1.04], p = 0.1291) [Escudier et al. 2009b].

Novel anti-angiogenic agents

While the successes of targeted therapies with antiangiogenic properties have established new standards of care in the treatment of advanced RCC, there remains a profound need for new agents or combinations of treatments that will improve clinical activity and diminish treatment-associated toxicities. For example, although sunitinib is now a preferred first-line treatment for patients with good or intermediate risk metastatic RCC, the updated ORR as presented in 2008 was 47%, while 67% of patients experienced grade 3 or 4 treatment-associated toxicity according to FDA prescribing information (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov) [Figlin et al. 2008]. Furthermore, to date only sunitinib and temsirolimus have demonstrated improvements in OS in clinical trials, albeit in quite different patient populations. Consequently, several novel targeted agents are currently being evaluated in clinical trials. Table 1 summarizes reported responses and toxicities associated with selected novel therapies for the treatment of metastatic RCC. Table 2 provides a possible treatment algorithm for metastatic RCC incorporating currently approved therapies and those undergoing evaluation in clinical trials.

Table 1.

Selected studies involving investigational agents for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

| Agent | Study | Patient population | Number of patients | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pazopanib | Phase III: pazopanib versus placebo | Metastatic dz | 435 | 9.2 versus 4.2 mos PFS | [Sternberg et al. 2009] |

| Untreated | 233 | 11.1 versus 2.8 mos PFS | |||

| Cytokine treated | 202 | 7.4 versus 4.2 mos PFS | |||

| Axitinib | Phase II | Cytokine-refractory | 52 | 44.2% ORR; median TTP 15.7 mos | [Rixe et al. 2007] |

| Phase II | Metastatic dz | 58 | [Dutcher et al. 2008] | ||

| Prior sorafenib | 15 | 27% ORR | |||

| Prior sorafenib + cytokine | 29 | 28% ORR | |||

| Prior sorafenib + sunitinib | 14 | 7% ORR | |||

| AV-951 | Phase II | No prior TKI | 245 | 28% ORR | [Bhargava et al. 2009] |

| Lenalidomide | Phase II | ≤1 prior Rx | 28 | 11% ORR | [Choueiri et al. 2006] |

| Phase II | Metastatic dz | 40 | 10% ORR | [Amato et al. 2008] | |

| Phase II | Metastatic dz | 14 | 0% ORR | [Patel et al. 2008] | |

| Perifosine | Phase II | Metastatic dz | 46 | 5% ORR | [Vogelzang et al. 2009] |

| Prior TKI | 31 | 3% ORR | |||

| Prior TKI + rapamycin analog | 15 | 7% ORR | |||

| Phase II | Prior TKI | 24 | 8% ORR | [Cho et al. 2009] | |

| AS1411 | Phase I | Advanced dz | 12 | 17% ORR | [Miller et al. 2006] |

dz, disease; mos, months; ORR, overall response rate; PFS, progression-free survival; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TTP, time to progression.

Table 2.

Treatment algorithm for metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

| Therapeutic setting | Patient features | Therapy options |

|---|---|---|

| First-line therapy | Good and intermediate risk | Sunitinib, pazopanib, bevacizumab + IFN, high-dose IL-2 Clinical trial: sunitinib then sorafenib versus sorafenib then sunitinib |

| Poor risk | Temsirolimus | |

| Any risk category | Clinical trial: pazopanib versus sunitinib; bevacizumab + temsirolimus versus bevacizumab + IFN-α (versus sunitinib) | |

| Second-line therapy | Prior cytokine therapy | Sorafenib, sunitinib |

| Prior anti-angiogenic TKI | Everolimus Clinical trial: temsirolimus versus sorafenib (following sunitinib failure) | |

| Prior cytokine or anti-angiogenic therapy | Clinical trial: axitinib versus sorafenib | |

| Prior rapamycin analog | Unknown |

IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Novel tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Pazopanib is a TKI that blocks VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, and c-Kit [Rini et al. 2008]. Pazopanib demonstrated an improved PFS compared with placebo in a randomized discontinuation trial involving 225 patients with no or one prior systemic therapy [Hutson et al. 2007, Hutson et al. 2008a]. Pazopanib treatment resulted in a low incidence of hand–foot syndrome, rash, and mucositis, toxicities that are frequently associated with other TKIs [Hutson et al. 2007, Hutson et al. 2008a]. Results of a double-blind, phase III study comparing pazopanib with placebo in untreated (N = 233) and cytokine-treated (N = 202) patients revealed an improvement in PFS with pazopanib (9.2 versus 4.2 months, p < 0.0000001) [Sternberg et al. 2009]. PFS was improved with pazopanib in both previously untreated (11.1 versus 2.8 months, p < 0.0000001) and in cytokine-pretreated patients (7.4 versus 4.2 months, p < 0.001) [Sternberg et al. 2009]. In October 2009, the FDA approved pazopanib for the treatment of advanced RCC. Pazopanib is now being compared with sunitinib as first-line therapy in an international phase III trial with an estimated enrollment of 876 patients with locally advanced or metastatic RCC who have received no prior systemic treatment (www.clinicaltrials.gov) [Sonpavde and Hutson, 2008]. The estimated study completion date is November 2010.

Axitinib is a TKI that inhibits VEGFR-1, -2, and -3 [Rixe et al. 2007]. A phase II study involving 52 patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic RCC demonstrated an ORR of 44.2% with axitinib treatment, including two CRs and 21 PRs, and a median time to progression (TTP) of 15.7 months [Rixe et al. 2007]. Median OS was 29.9 months [Rixe et al. 2007]. However, it should be noted that 22 patients did not have any unfavorable risk factors, and 28 patients experienced grade 3 or 4 AEs, the most frequent being hypertension, diarrhea, and fatigue [Rixe et al. 2007]. In a phase II study involving patients who were refractory to sorafenib (N = 15), sorafenib and cytokine therapy (N = 29), or sorafenib and sunitinib therapy (N = 14), response rates to axitinib were 27%, 28%, and 7%, respectively, demonstrating activity of axitinib in VEGFR-TKI-refractory patients [Dutcher et al. 2008; Sonpavde and Hutson, 2008]. A phase III study (N = 540) is currently enrolling with PFS as the primary endpoint that compares axitinib with sorafenib in the treatment of patients who have failed one prior systemic therapy (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Tivozanib (AV-951) is another pan-VEGFR TKI that is being evaluated in a randomized discontinuation phase II study of patients with metastatic RCC who had received no prior VEGF-targeted therapy [Bhargava et al. 2009]. Following 16 weeks of treatment with AV-951, patients are evaluated for tumor response. Those in whom a ≥25% decrease in tumor size is achieved continue with AV-951, while those with <25% change in tumor burden are randomized to receive treatment with either AV-951 or placebo [Bhargava et al. 2009]. Interim data from this trial, presented at ASCO GU 2009 meeting revealed that either CR or PR was achieved in 28% of 245 evaluable patients at 16 weeks, while 63% had stable disease [Bhargava et al. 2009]. Hypertension was the most common all-grade, treatment-related AE, affecting 42% of patients. Minimal all-grade fatigue, diarrhea, and mucositis were observed (all <10%) [Bhargava et al. 2009].

A host of additional TKIs that target critical components of angiogenesis are currently under investigation. These include cediranib, which blocks VEGFR-1 and -2, c-Kit, PDGFRβ, and Flt4; vandetanib, which inhibits EGFR and VEGFR-2; ABT-869, an inhibitor of the VEGFRs, PDGFRs, Flt3, and c-Kit; BAY 73-4506, which targets the VEGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), PDGFR, c-Kit, and RET tyrosine kinases, as well as the Raf and MAPK serine/threonine kinases; and GSK-089, a Met and VEGFR-2 inhibitor [Sonpavde and Hutson, 2008].

Non-TKI anti-angiogenic therapies

In addition to TKIs, agents that target angiogenesis by alternative mechanisms are also being studied in phase I and phase II clinical trials. Aflibercept, also known as VEGF Trap, binds VEGF directly. Unlike bevacizumab, which is an antibody to VEGF, aflibercept is derived from extracellular portions of VEGFR-1 and -2 [Holash et al. 2002]. A phase II randomized trial of aflibercept in patients with unresectable or metastatic RCC is underway (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Lenalidomide, a derivative of thalidomide, possesses both anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory properties. Lenalidomide results in diminished endothelial cell migration in response to angiogenic factors bFGF, VEGF, and TNF-α [Choueiri et al. 2006]. Three small phase II studies have examined the efficacy of lenalidomide in the treatment of metastatic RCC. In an open-label study involving 28 patients who had received at most one prior systemic therapy with the primary endpoint of ORR, PR was achieved in 3 patients (11%) lasting greater than 15 months, and 11 of 28 patients had stable disease for greater than 3 months [Choueiri et al. 2006]. Grade 3 or 4 AEs included fatigue (11%), skin toxicity (11%), and neutropenia (36%) [Choueiri et al. 2006]. In a second trial, 40 participants with metastatic disease received lenalidomide treatment with the primary endpoint of tumor response rate [Amato et al. 2008]. Of 39 evaluable patients, 23 (59%) had previously received immunotherapy or chemotherapy. One patient was observed to have a CR, 3 had PRs, and 21 had stable disease. The median duration of response was 6 months (2–22 month range), and median OS was 17 months [Amato et al. 2008]. The third reported lenalidomide trial in patients with RCC enrolled 14 patients; none experienced a CR or PR, while 8 (57%) had stable disease with a median TTP of 3 months [Patel et al. 2008].

Combination therapy and sequential therapy

An area of active investigation is to determine the optimum combination or sequencing of therapies for metastatic RCC. Combining established anti-angiogenic or immunomodulatory therapies presents an attractive approach to maximizing tumor response, but may result in excess toxicity. For example, despite yielding a promising response rate of 52% in a phase I study, the combination of sunitinib and bevacizumab was poorly tolerated and required dose reductions or discontinuation in a significant number of patients [Feldman et al. 2008]. The FDA issued a safety alert regarding the combination of sunitinib and bevacizumab due to the high percentage of patients who experienced Grade 3/4 hypertension, hematologic complications, and vascular AEs (www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2008/MAHA_DHCP.pdf). A phase I study evaluating the combination of sorafenib and bevacizumab also yielded relatively high response rates, as 21 of 46 patients (46%) experienced a PR by RECIST criteria following two cycles of treatment [Sosman et al. 2008]. However, bevacizumab appeared to significantly increase sorafenib-associated toxicities, particularly hand–foot syndrome, and combining both agents reduced the maximal tolerated doses of each drug to a fraction of the full dose of each given as single-agent therapy [Sosman et al. 2008]. In addition, a phase I trial combining sunitinib with temsirolimus was terminated following the accrual of only three patients due to significant toxicity observed at low starting doses of both drugs [Fischer et al. 2008].

Despite these somewhat discouraging findings from combination studies, two ongoing studies have been designed to assess whether temsirolimus may be effectively combined with bevacizumab. TORAVA is a phase II multicenter, randomized, open-label study in which patients receive temsirolimus plus bevacizumab, IFN-α plus bevacizumab, or sunitinib as first-line systemic treatment (www.clinicaltrials.gov). INTORACT is a phase III randomized, open-label trial comparing bevacizumab plus temsirolimus with bevacizumab plus IFN-α in the first line, with an estimated enrollment of 800 patients (www.clinicaltrials.gov). In addition, the RECORD-2 study compares the safety and efficacy of everolimus and bevacizumab with IFN-α and bevacizumab, with an estimated enrollment of 360 patients (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Several clinical trials are underway to evaluate optimal sequencing of targeted therapies. Everolimus is the only agent currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of kidney cancer following progression on TKI therapy. A phase I/II study of the combination of temsirolimus plus bevacizumab in TKI-refractory disease is underway [Merchan et al. 2009]. The accrual goal for the phase II portion of this trial is 40 patients, with the primary goal being to ascertain the percentage of patients free of disease progression at 6 months, and secondary endpoints of toxicity and response rate [Merchan et al. 2009]. At interim analysis, PR was achieved in 4 of 25 (16%) of evaluable patients, while 18 of 25 patients (72%) had stable disease [Merchan et al. 2009]. An international, randomized trial with an estimated enrollment of 480 patients will compare the efficacy and tolerability of temsirolimus versus sorafenib following sunitinib failure, while a phase III study is ongoing that compares axitinib with sorafenib following disease progression on sunitinib treatment in a planned 540 patients, with PFS as the primary endpoint (www.clinicaltrials.gov). An alternative phase III study does not assume the superiority of sunitinib in the first line and randomizes previously untreated patients with low or intermediate Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) prognostic scores to receive sunitinib followed by sorafenib or sorafenib followed by sunitinib, with total PFS as the primary endpoint (www.clinicaltrials.gov). In addition, a study with an estimated enrollment of 390 patients (RECORD-3) is planned to assess the efficacy and safety of treatment with sunitinib followed by everolimus versus treatment with everolimus followed by sunitinib, with PFS as the primary endpoint (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Predicting outcomes and toxicities in the era of anti-angiogenic targeted therapies

The MSKCC risk system stratifies patients with metastatic RCC into poor-, intermediate-, and favorable-risk categories based on the number of adverse clinical and laboratory parameters present. Poor prognostic factors are a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) <80, time from diagnosis to treatment (with IFN-α) <12 months, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) >1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), corrected serum calcium >10.0 mg/dl, and hemoglobin less than the lower limit of normal (LLN) [Motzer et al. 1999]. Patients in the favorable risk group have no poor prognostic factors, those in the intermediate risk category have one or two poor prognostic factors, and patients with poor risk RCC have more than two poor prognostic factors. This model was externally validated and extended to include prior radiotherapy and hepatic, pulmonary, or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases among the poor prognostic factors that independently predicted decreased survival [Mekhail et al. 2005]. However, the MSKCC prognostic factors model was generated at a time when immunotherapy comprised the standard of treatment for metastatic RCC [Mekhail et al. 2005; Motzer et al. 1999, 2002].

To identify prognostic factors for OS in patients with metastatic RCC treated with VEGF-targeted therapies, Heng and colleagues evaluated baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics and outcomes for 645 patients who had received treatment with sunitinib (396), sorafenib (200), or bevacizumab (49) [Heng et al. 2009]. The study identified four of the five MSKCC poor prognostic factors (hemoglobin < LLN, corrected calcium > ULN, Karnofsky PS < 80, and time from diagnosis to treatment initiation <1 year) to be independent predictors of diminished survival, thereby validating elements of the MSKCC model in this patient population [Heng et al. 2009]. The authors also identified absolute neutrophil count > ULN and platelet count > ULN as independent adverse prognostic factors.

In addition to these clinical, cytologic, and metabolic prognostic factors, the molecular makeup of an individual’s tumor cells may predict response to therapy. For example, VHL loss-of-function mutations appear to correlate with chance of responding to VEGF-targeted therapy [Choueiri et al. 2008]. VHL-deficient tumors also show mTOR-dependent increased uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG); therefore, positron emission tomography may have early predictive utility in evaluating the response to temsirolimus or everolimus treatment [Thomas et al. 2006]. A recent report also sheds new light on the potential importance of differential expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in RCC. Nathanson and colleagues analyzed VHL status and HIF-α expression in 160 primary tumors from patients with RCC [Gordan et al. 2008]. The authors identified three subtypes of RCC distinguished by VHL and HIF-α expression: those expressing wild-type VHL protein (VHL WT), tumors deficient in VHL that express both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (H1H2), and VHL-deficient tumors that express only HIF-2α (H2) [Gordan et al. 2008]. Whereas VHL WT and H1H2 tumors showed activation of the Akt/mTOR and Erk/MAPK signaling pathways, proliferation of H2 tumors appeared to be driven by c-Myc activation [Gordan et al. 2008]. Interestingly, HIF-1α antagonizes c-Myc activity in certain settings [Gordan et al. 2008; Kaelin, 2008; Kaelin and Ratcliffe, 2008]. One can speculate that VHL WT and H1H2 tumors may respond better to growth factor receptor inhibitors such as sunitinib and sorafenib than H2 tumors [Gordan et al. 2008; Kaelin, 2008].

Current data for selecting the appropriate first-line treatment for a given patient is limited. There is rationale for choosing alternative treatments based on a patients MSKCC risk category and available PFS and OS data. For example, sunitinib, or the combination of bevacizumab plus IFN, are viable first-line options for many patients with low or intermediate risk metastatic RCC. When choosing between these options, or among available second-line therapies following disease progression, we must also take into account the specific toxicity profiles of these targeted therapies as they relate to the individual patient. Hypertension, hand–foot syndrome, fatigue, leukopenia, diarrhea, and increased lipase are among the most common Grade 3 or 4 toxicities associated with sunitinib and sorafenib, while the most common severe side effects of temsirolimus include fatigue, mucositis, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperglycemia, and hypophosphatemia [Hutson et al. 2008b]. The combination of bevacizumab and IFN, meanwhile, is most frequently associated with diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, and proteinuria, and increases the risk for both arterial and venous thromboembolic events [Schmidinger and Zielinski, 2009]. Patient comorbidities are therefore important considerations in treatment selection, and molecular predictors of treatment-related toxicities are being investigated. For example, select non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) may distinguish patients at risk for experiencing severe sunitinib-associated toxicities from those without severe side effects [Faber et al. 2008].

Evolving treatment approaches

Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling

The rapamycin analogs temsirolimus and everolimus have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of metastatic RCC. However, our growing understanding of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade provides insight into potential means of improving on the outcomes achieved by rapamycin analog treatment [Courtney and Choueiri, 2009]. For example, rapamycin analogs inhibit the mTORC1 complex, a key regulator of protein synthesis and cell-cycle entry [Le Tourneau et al. 2008]. However, rapamycin may not be an effective inhibitor of mTORC2, which contributes to Akt activation [Meric-Bernstam and Gonzalez-Angulo, 2009]. Furthermore, rapamycin treatment can result in Akt activation in some circumstances, for example through loss of mTORC1-mediated negative feedback upstream of PI3K (Figure 1) [Meric-Bernstam and Gonzalez-Angulo, 2009]. ATP competitive inhibitors that can effectively block both mTORC1 and mTORC2 may have improved clinical utility. Direct inhibitors of PI3K, or dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors, are being evaluated in early-phase clinical trials [Yuan and Cantley, 2008]. In addition, perifosine, a heterocyclic alkylphospholipid that is intended to alter Akt signaling by disrupting interaction with membrane phospholipids, has demonstrated limited clinical response for patients with RCC. In a phase II study involving 46 patients who had received one prior VEGFR inhibitor (Group A, N = 31) or prior VEGFR inhibitor and mTOR inhibitor therapy (Group B, N = 15), 1 of 30 evaluable patients in Group A and 1 of 14 in Group B experienced a PR, while 12/30 and 7/14 had stable disease lasting more than 12 weeks one patient experienced a PR and 10 had stable disease at the time of analysis [Vogelzang et al. 2009]. In a second phase II trial of 24 patients with metastatic RCC refractory to either sunitinib or sorafenib, PR was realized in 2 patients, and 10 patients had stable disease >12 weeks, resulting in a 50% PFS at 12 weeks [Cho et al. 2009].

Aptamers as targeted therapeutic agents

Aptamers are short peptides or oligonucleotides, either RNA or single-stranded DNA, that form stable structures that resist degradation and are capable of binding target proteins with high affinity [Ireson and Kelland, 2006]. AS1411 is a 26-nucleotide DNA aptamer that binds nucleolin. Nucleolin is proposed to play a role in mRNA stabilization and ribosomal assembly, and AS1411 appears to destabilize mRNA [Soundararajan et al. 2008; Ireson and Kelland, 2006]. An extended phase I dose-escalation study of AS1411 included 12 patients with RCC [Miller et al. 2006]. One patient experienced a CR, one had a partial response, 9 had stable disease, and none experienced serious toxicities [Miller et al. 2006]. A single-arm phase II study of AS1411 in patients with RCC who have failed prior treatment recently completed accrual (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Conclusions

Advances in our understanding of the molecular events necessary for RCC growth and survival have paved the way for the development of targeted therapies that are now the standard of care for patients with metastatic disease. The recent introduction of an array of compounds with anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative properties has dramatically expanded the treatment options for patients with metastatic RCC. However, despite these advances, there is much room for improvement. The majority of patients fail to experience significant and durable tumor response to currently approved TKIs, rapamycin analogs, and VEGF-targeted antibody therapy, and improvements in OS observed with these compounds in phase III trials are still not ideal. In addition, toxicities associated with these treatments are common and can be substantial. Ongoing clinical trials with novel agents look to improve upon the successes realized with the introduction of these drugs with increased response rates and diminished severity of side effects.

Conflict of interest statement

K.D. Courtney receives research support from an ASCO Young Investigator Award and a Genentech, Inc. Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney Cancer Career Development Award. T.K. Choueiri receives funding support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney Cancer Career Development Award.

References

- Amato R.J., Hernandez-Mcclain J., Saxena S., Khan M. (2008) Lenalidomide therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 31: 244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, P., Esteves, B., Lipatov, O.N., Nosov, D.A., Lyulko, A.A., Anischenko, A.O. et al. (2009) Activity and Safety of Av-951, a Potent and Selective VEGFR1, 2, and 3 Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Interim Results of a Phase II Randomized Discontinuation Trial. In ASCO 2009 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

- Cho D.C., Figlin R.A., Flaherty K.T., Michaelson D., Sosman J.A., Ghebremichael, M., et al. (2009) A phase II trial of perifosine in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) who have failed tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI). J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract 5101 [Google Scholar]

- Choueiri T.K., Dreicer R., Rini B.I., Elson P., Garcia J.A., Thakkar S.G., et al. (2006) Phase ii study of lenalidomide in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 107: 2609–2616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choueiri T.K., Vaziri S.A., Jaeger E., Elson P., Wood L., Bhalla I.P., et al. (2008) Von hippel–lindau gene status and response to vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 180: 860–865;, discussion 865–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H.T., Mcgovern F.J. (2005) Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 353: 2477–2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppin C., Le L., Porzsolt F., Wilt T. (2008) Targeted therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD006017–CD006017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney K.D., Choueiri T.K. (2009) Optimizing recent advances in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep 11: 218–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher J.P., Wilding G., Hudes G.R., Stadler W.M., Kim S., Tarazi J.C., et al. (2008) Sequential axitinib (AG-013736) therapy of patients (Pts) with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer (RCC) refractory to sunitinib and sorafenib, cytokines and sorafenib, or sorafenib alone. J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5127 [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B.J., Bellmunt J., Negrier S., Melichar B., Bracarda S., Ravaud A., et al. (2009b) Final results of the phase III, randomized, double-blind AVOREN trial of first-line bevacizumab (BEV) + interferon-a2a (IFN) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract 5020 [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B., Eisen T., Stadler W.M., Szczylik C., Oudard S., Siebels M., et al. (2007a) Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B., Eisen T., Stadler W.M., Szczylik C., Oudard S., Staehler M., et al. (2009a) Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 27: 3312–3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B., Pluzanska A., Koralewski P., Ravaud A., Bracarda S., Szczylik C., et al. (2007b) Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 370: 2103–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B., Szczylik C., Eisen W.M., Schwartz B., Shan M., Bukowski R.M. (2005) Randomized phase III trial of the Raf kinase and VEGFR inhibitor sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 23: Abstract 4510–Abstract 4510 [Google Scholar]

- Faber P.W., Vaziri S.A., Wood L., Nemec L., Elson P., Garcia J.A., et al. (2008) Potential non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (NSSNPS) associated with toxicity in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC) patients (Pts) treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5009 [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D.R., Ginsberg M.S., Baum M., Flombaum C., Hassoun H., Velasco S., et al. (2008) Phase I trial of bevacizumab plus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlin R.A., Hutson T.E., Tomczak P., Michaelson M.D., Bukowski R.M., Negrier S., et al. (2008) Overall survival with sunitinib versus interferon (IFN)-alfa as first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5024 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P., Patel P., Carducci M.A., Mcdermott D.F., Hudes G.R., Lubiniecki G.M., et al. (2008) Phase I study combining treatment with temsirolimus and sunitinib malate in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 16020 [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe G., Fisher R.I., Rosenberg S.A., Sznol M., Parkinson D.R., Louie A.C. (1995) Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol 13: 688–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshayan A.R., Brick A.J., Choueiri T.K. (2008) Predicting outcome to VEGF-targeted therapy in metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma: data from recent studies. Future Oncol 4: 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordan J.D., Lal P., Dondeti V.R., Letrero R., Parekh K.N., Oquendo C.E., et al. (2008) Hif-alpha effects on c-myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Cell 14: 435–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng D.Y., Choueiri T.K. (2009) Non-clear cell renal cancer: features and medical management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 7: 659–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng, D.Y., Xie, W., Regan, M., Warren, M.A., Cheng, T., North, S.A. et al. (2009) Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival (OS) in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) Treated with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-Targeted Agents: Results from a Large Multicenter Study. In ASCO 2009 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holash J., Davis S., Papadopoulos N., Croll S.D., Ho L., Russell M., et al. (2002) Vegf-trap: a VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11393–11398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudes G., Carducci M., Tomczak P., Dutcher J., Figlin R., Kapoor A., et al. (2007) Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 2271–2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson T.E., Davis I.D., Machiels J.H., De Souza P.L., Baker K., Bordogna W., et al. (2008a) Biomarker analysis and final efficacy and safety results of a phase II renal cell carcinoma trial with pazopanib (GW786034), a multi-kinase angiogenesis inhibitor. J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5046 [Google Scholar]

- Hutson T.E., Davis I.D., Machiels J.H., De Souza P.L., Hong B.F., Rottey S., et al. (2007) Pazopanib (GW786034) is active in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (Rcc): interim results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial (RDT). J Clin Oncol 25: 5031–5031 [Google Scholar]

- Hutson T.E., Figlin R.A. (2007) Evolving role of novel targeted agents in renal cell carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park) 21: 1175–1180, discussion 1184, 1187, 1190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson T.E., Figlin R.A., Kuhn J.G., Motzer R.J. (2008b) Targeted therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an overview of toxicity and dosing strategies. Oncologist 13: 1084–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireson C.R., Kelland L.R. (2006) Discovery and development of anticancer aptamers. Mol Cancer Ther 5: 2957–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Hao Y., Xu J., Thun M.J., et al. (2009) Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59: 225–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G., Jr, (2004) The von hippel–lindau tumor suppressor gene and kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res 10: 6290S–6295S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G., Jr, (2008) Kidney cancer: now available in a new flavor. Cancer Cell 14: 423–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G., Jr,, Ratcliffe P.J. (2008) Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the hif hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30: 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, A., Motzer, R., Figlin, R., Escudier, B., Oudard, S., Porta, C. et al. (2009) Updated data from a phase III randomized trial of everolimus (RAD001) versus PBO in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). In ASCO 2009 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, Abstract 278.

- Le Tourneau C., Faivre S., Serova M., Raymond E. (2008) Mtorc1 inhibitors: is temsirolimus in renal cancer telling us how they really work? Br J Cancer 99: 1197–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdermott D.F., Atkins M.B. (2006) Interleukin-2 therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma—predictors of response. Semin Oncol 33: 583–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail T.M., Abou-Jawde R.M., Boumerhi G., Malhi S., Wood L., Elson P., et al. (2005) Validation and extension of the memorial sloan-kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 23: 832–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchan J.R., Pitot H.C., Qin R., Liu G., Fitch T.R., Picus J., et al. (2009) Phase I/II trial of CCI 779 in advanced renal cell carcinoma (Rcc): safety and activity in RTKI refractory RCC patients. J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract 5039 [Google Scholar]

- Meric-Bernstam F., Gonzalez-Angulo A.M. (2009) Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 27: 2278–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.M., Laber, D.A., Bates, P.J., Trent, J.O., Taft, B.S., Kloecker, G.H. et al. (2006) Extended Phase I Study of AS1411 in Renal and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers. In ESMO Istanbul 2006.

- Motzer R.J., Bacik J., Murphy B.A., Russo P., Mazumdar M. (2002) Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 20: 289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R.J., Escudier B., Oudard S., Hutson T.E., Porta C., Bracarda S., et al. (2008) Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet 372: 449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R.J., Hutson T.E., Tomczak P., Michaelson M.D., Bukowski R.M., Rixe O., et al. (2007) Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R.J., Mazumdar M., Bacik J., Berg W., Amsterdam A., Ferrara J. (1999) Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 17: 2530–2540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R.J., Michaelson M.D., Redman B.G., Hudes G.R., Wilding G., Figlin R.A., et al. (2006a) Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 24: 16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R.J., Rini B.I., Bukowski R.M., Curti B.D., George D.J., Hudes G.R., et al. (2006b) Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA 295: 2516–2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrier S., Perol D., Ravaud A., Chevreau C., Bay J.O., Delva R., et al. (2007) Medroxyprogesterone, interferon alfa-2a, interleukin 2, or combination of both cytokines in patients with metastatic renal carcinoma of intermediate prognosis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 110: 2468–2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P.H., Kondagunta G.V., Schwartz L., Ishill N., Bacik J., Deluca J., et al. (2008) Phase II trial of lenalidomide in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest New Drugs 26: 273–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini B.I., Campbell S.C., Escudier B. (2009a) Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 373: 1119–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini B.I., Halabi S., Rosenberg J.E., Stadler W.M., Vaena D.A., Atkins J.N., et al. (2009b) Bevacizumab plus interferon-alpha versus interferon-alpha monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results of overall survival for CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract LBA5019 [Google Scholar]

- Rini B.I., Halabi S., Rosenberg J.E., Stadler W.M., Vaena D.A., Ou S.S., et al. (2008) Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol 26: 5422–5428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rixe O., Bukowski R.M., Michaelson M.D., Wilding G., Hudes G.R., Bolte O., et al. (2007) Axitinib treatment in patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic renal-cell cancer: a phase II study. Lancet Oncol 8: 975–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidinger M., Zielinski C.C. (2009) Novel agents for renal cell carcinoma require novel selection paradigms to optimise first-line therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 35: 289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonpavde G., Hutson T.E. (2008) Novel antiangiogenic agents in the treatment of refractory renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 6: s29–s36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosman J.A., Flaherty K.T., Atkins M.B., Mcdermott D.F., Rothenberg M.L., Vermeulen W.L., et al. (2008) Updated results of phase I trial of sorafenib (S) and bevacizumab (B) in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer (mRCC). J Clin Oncol 26: Abstract 5011 [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan S., Chen W., Spicer E.K., Courtenay-Luck N., Fernandes D.J. (2008) The nucleolin targeting aptamer AS1411 destabilizes bcl-2 messenger RNA in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 68: 2358–2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg C.N., Szczylik C., Lee P., Salman P.V., Mardiak J., Davis I.D., et al. (2009) A randomized, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in treatment-naive and cytokine-pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract 5021 [Google Scholar]

- Strumberg D., Richly H., Hilger R.A., Schleucher N., Korfee S., Tewes M., et al. (2005) Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the novel raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor bay 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 23: 965–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczylik C., Demkow T., Staehler M., Rolland F., Negrier S., Hutson T.E., et al. (2007) Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with sorafenib versus interferon in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: final results. J Clin Oncol 25: 5025–5025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G.V., Tran C., Mellinghoff I.K., Welsbie D.S., Chan E., Fueger B., et al. (2006) Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mtor in kidney cancer. Nat Med 12: 122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang N.J., Hutson T.E., Samlowski W., Somer B., Richey S., Alemany C., et al. (2009) Phase II study of perifosine in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) progressing after prior therapy (Rx) with a VEGF receptor inhibitor. J Clin Oncol 27: Abstract 5034 [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T.L., Cantley L.C. (2008) PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme. Oncogene 27: 5497–5510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]