Abstract

Objectives

Open retroperitoneal lymph node dissection has been traditionally used for the management of patients with nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors (NSGCTs). Over the last decade, laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (LRPLND) has gained popularity in several highly specialized centers.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the English-language literature with regard to LRPLND. The perioperative and oncologic outcomes for patients with low stage NSGCTs who underwent LRPLND are summarized in this review with particular emphasis on contemporary studies.

Results

Initially only used for staging, LRPLND has evolved to a therapeutic procedure capable of replicating the templates used for open RPLND. Perioperative outcomes including operative time, conversion rates and complications improve with surgeon experience and are acceptable at high volume centers. Oncologic outcomes are promising, but require longer term follow-up and the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy in many studies limits comparison to that of the open technique.

Conclusion

LRPLND has been demonstrated to be feasible and safe at large volume institutions with experienced laparoscopic surgeons. LRPLND was originally performed as a staging procedure in patients with NSGCTs but has evolved into a therapeutic operation with early reports demonstrating short hospital stays and minimal morbidity. Further studies in larger cohorts of patients with longer term follow up are required to define the exact role of LRPLND.

Keywords: testicular cancer, laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

Introduction

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy in men between the ages of 15–35 [Carver and Shenfield, 2005]. Fortunately, testicular cancer is also one of the most curable solid organ neoplasms due in large part to an excellent multimodal treatment paradigm that includes effective platinum based chemotherapy. Treatment options for men with low stage, marker negative nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors (NSGCTs) following orchiectomy include intensive surveillance protocols, surgery or cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The rationale for retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) in the management of NSGCTs includes a well-documented knowledge of the pattern of lymphatic spread to the retroperitoneum, the potential for RPLND to be curative in patients with low volume retroperitoneal disease, and the 20–30% false negative rate in the radiographic staging of patients with clinical stage I disease [Stephenson and Shenfield, 2005].

Traditionally RPLND for NSGCTs has been performed via an open approach through a large midline transabdominal incision. Over the past two decades, minimally invasive surgical approaches for the treatment of various malignancies have become popular. Ideally minimally invasive surgery should offer patients the benefits of decreased blood loss, less pain, improved cosmesis, and a shorter convalescence time without compromising the oncologic efficacy and intent of the procedure. The benefits and efficacy of laparoscopy have clearly been shown with regard to oncologic renal and prostate surgery [Colombo et al. 2008; Patel et al. 2008]. The role of laparoscopic RPLND (LRPLND) in the management of patients with stage I and II NSGCTs has been far more controversial. The excellent long-term oncologic outcomes of open RPLND for patients with low stage NSGCTs remain the gold standard [Richie, 2005]. The lack of acceptance of LRPLND in large part is due to initial reports in which the procedure was used for staging purposes without attempting to replicate the open technique. As laparoscopic skills have evolved, techniques for LRPLND have also evolved. LRPLND is now being performed within specialized centers with therapeutic intent, with boundaries of dissection identical to those of the open approach.

The rationale for RPLND in patients with stage I and II NSGCTs

While primary chemotherapy is favored in Europe, traditionally RPLND has been the management strategy of choice for high risk clinical stage I patients in the US. RPLND can accurately stage the retroperitoneum and thus positively identify harboring metastases. Patients with pathological stage I disease are spared the toxicity and morbidity of any additional therapy since ≥90% experience long-term disease-free survival with surgery alone. Patients with pathological stage II disease can learn more about the extent of the disease and make informed decisions regarding further therapy. Of patients in this group who harbor small volume retroperitoneal disease (pN1) a properly performed RPLND can be curative in approximately 70% and thus chemotherapy can also be avoided in this setting [Rabbani et al. 2001; Donohue et al. 1993; Richie and Kantoff, 1991]. Since the retroperitoneum is the most frequent site of chemoresistant malignant germ cell tumor and teratoma, both of these processes are minimized with RPLND [Baniel et al. 1995]. Some groups advocate RPLND as the treatment of choice for all men with clinical stage I NSGCT with teratoma in the orchiectomy specimen given the increased propensity of harboring teratoma in the retroperitoneum [Sheinfeld et al. 2003]. RPLND eliminates these chemoresistant elements and maximizes therapeutic efficacy.

Patients with clinical stage IIA or IIB NSGCTs are candidates for either primary chemotherapy or RPLND. The risk of systemic relapse following RPLND is directly related to the extent of disease. Patients with pN2 or N3 disease have a systemic relapse rate of 50% and are generally offered adjuvant chemotherapy [Rabbani et al. 2001; Xiao et al. 1997].

RPLND templates

One of the most dreaded complications of RPLND is loss of ejaculatory function and infertility in this young group of patients. In early experience, RPLND was performed with aggressive and wide boundaries (bilateral and suprahilar) that often resulted in loss of ejaculatory function. However, mapping studies of retroperitoneal metastases by several groups led to the development of modified RPLND templates [Weissbach and Boedefeld, 1997; Donohue et al. 1982; Ray et al. 1974]. These templates minimize dissection in areas where metastatic disease is rare in an effort to simultaneously maximize ejaculatory function and oncologic efficacy. Unilateral modified templates avoid dissection below the inferior mesenteric artery and thus minimize risk of injury to the sympathetic nerve fibers in this region. Additionally by avoiding dissection of efferent sympathetic fibers emanating from the contralateral sympathetic trunk, emission and ejaculation are maximized. Spontaneous ejaculatory rates with modified template dissections are approximately 90% [Doerr et al. 1993; Richie, 1990].

Increased understanding of the local neuroanatomy led to the development of nerve sparing techniques to prospectively identify and preserve the sympathetic trunks, postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers and the hypogastric plexus. With the nerve sparing technique, ejaculatory function is preserved in 92 to 100% of patients [Heidenreich et al. 2003; Donohue et al. 1990]. The use of this technique allows for bilateral dissections without compromise of ejaculatory function and has replaced modified template dissections at select centers.

Eggener et al. retrospectively examined the incidence of disease outside five different modified templates [Eggener et al. 2007]. They concluded that a significant number of men harbored occult disease beyond these templates and thus advocated full bilateral nerve sparing dissections on all patients. This study not only included patients with clinical stage I NSGCT, but also those with clinical stage IIA disease. The authors found that for right sided templates, inclusion of para-aortic, preaortic and right common iliac regions decreased the incidence of extra template disease to 2%. For left templates, inclusion of the interaortocaval, precaval, para-caval and left common iliac regions decreased the incidence of extra template disease to 3%. Interestingly, for certain modified template dissections, the incidence of extra template disease without intra template disease was zero. Thus, the use of modified templates within the appropriate anatomic boundaries remains a valid and effective option.

LRPLND technique

Various techniques for LRPLND have been described in the literature including both transperitoneal and extraperitoneal. We favor a transperitoneal approach at our institution because it allows for a larger, more familiar working space. Furthermore, the transperitoneal approach facilitates bilateral dissections when warranted. We prefer to position the patient supine, with four evenly spaced midline 10 mm trocars (Figure 1). By using this positioning and trocar placement, transition to a bilateral LRPLND is least cumbersome and does not require patient repositioning.

Figure 1.

LRPLND is performed with patient supine on operating room table and both arms tucked. Supine positioning allows for easy conversion to full bilateral LRPLND when warranted.

Once laparoscopic access is achieved, the operating room table is tilted maximally toward the surgeon in order optimize medialization of the bowel. The white line of toldt is then incised sharply. It is important to incise the peritoneum as inferiorly as possible, to aid in dissection of the gonadal vein as it enters the internal ring. A laparoscopic paddle retractor is particularly useful for medial retraction of the bowel and alleviates the need to position the patient in a modified flank position. Once the retroperitoneum is fully exposed, the peritoneum is incised over the internal ring exposing the orchiectomy suture, which is then circumferentially dissected. Once the gonadal vein is completely dissected distally, it is followed to its origin proximally and ligated. Full, modified right or left nerve sparing template is then performed. A combination of blunt and sharp dissection is used to separate the lymphatic tissue from the great vessels. Laparoscopic clips are applied during splitting and rolling of the lymphatic tissue in order to minimize the risk of postoperative chylous ascites. The 5 mm Ligasure device (Valleylab, Boulder, CO) is also extremely useful during dissection as it seals small vessels that can potentially cause nuisance bleeding and slow down dissection. The boundaries of our right sided template include the ipsilateral ureter laterally, the bifurcation of the ipsilateral common iliac artery inferiorly, the ipsilateral renal hilum superiorly and the pre and para-aortic lymph nodes laterally (sparing the IMA) (Figure 2). A complete interaortocaval dissection is also performed and all precaval, para-caval and retrocaval nodal tissue is removed (Figure 3). The boundaries for the left sided template include the ipsilateral ureter laterally, the bifurcation of the ipsilateral common iliac artery inferiorly, the ipsilateral renal hilum superiorly and the precaval and para-caval lymph nodes laterally (Figure 4). A complete interaortocaval dissection is performed, and all preaortic, para-aortic and retroaortic nodal tissue is removed.

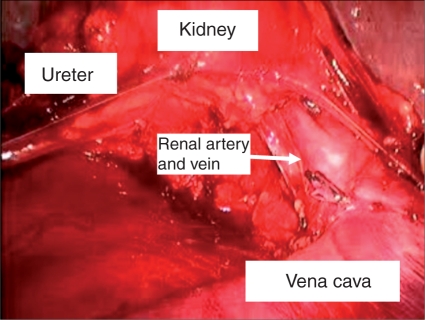

Figure 2.

Portion of right template LRPLND illustrating renal hilum superiorly, right ureter laterally and inferior vena cava medially.

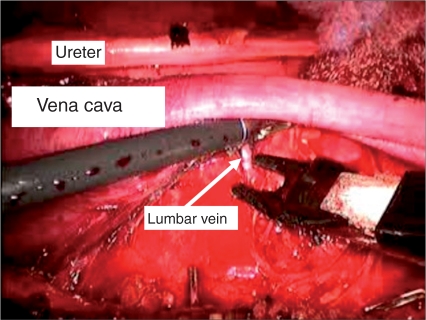

Figure 3.

Interaortocaval lymph node dissection, with transection of lumbar vein to allow access to retrocaval nodes.

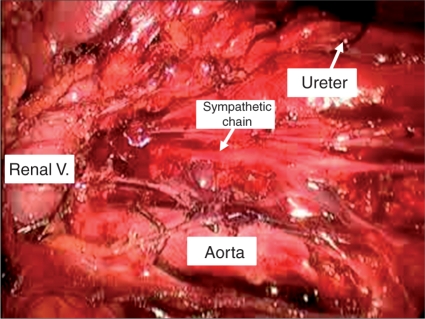

Figure 4.

Portion of left-sided nerve sparing template illustrating preserved sympathetic nerve fibers, renal hilum superiorly, left ureter laterally and aorta medially.

LRPLND for patients with stage I NSGCT

Critics of primary RPLND for the management of clinical stage I disease argue that the majority of men are over treated and exposed to the morbidity and side effects of surgery. LRPLND allows for decreased morbidity, while maintaining the benefits of surgery for testicular cancer patients. In its infancy, LRPLND was used as a staging tool without attempts to replicate the therapeutic goals of open surgery [Winfield, 1998]. Patients who were found to have positive lymph nodes on frozen section at the time of LRPLND were converted to an open procedure and those upstaged pathologic stage II after surgery were universally given chemotherapy [Rasswiler et al. 1996; Janetschek et al. 1994]. Although not advocated many (including our group), continue to use this approach today at some centers. More recently, as laparoscopic experience has evolved, several centers are performing ‘therapeutic’ LRPLND with the goal of duplicating open RPLND. Complete template LRPLND, with retrocaval and retroaortic dissection, has proven to be technically feasible. Additionally, full bilateral nerve sparing LRPLND has also been reported in the literature, thus allowing for this to be performed laparoscopically when indicated [Steiner et al. 2008].

LRPLND series have now been reported from multiple centers world wide. It is difficult to compare these reports to those of large open RPLND series because the follow-up is generally shorter and the significant majority of patients in LRPLND series with positive nodes received adjuvant chemotherapy. Table 1 illustrates outcomes from several contemporary large LRPLND series. These reports confirm that LRPLND can be performed safely with minimal morbidity and low open conversion rates. Uncontrollable bleeding is the most common reason reported for conversion to an open procedure. Mean operative times were 138–261 minutes, with mean length of hospitalizations (LOS) varying from 1.5 to 6 days. Mean blood loss ranged from 50 to 145 mLs and the need for blood transfusion was rare.

Table 1.

Contemporary LRPLND series for patients with stage I NSGCTs.

| Series | N | Follow-up (Months) | OR Time (Mins) | Open Conversion (%) | Length of Stay (days) | EBL (mL) | Node positive | Adjuvant Chemo | p0 Recurrences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cresswell et al. 2008 | 79 | 84 | 177 | 1.3 | 6 | NR | 19 | 19 | 3 pulmonary |

| 2 RP outside template | |||||||||

| 2 biochemical | |||||||||

| 1 port site | |||||||||

| Skolarus et al. 2008 | 19 | 23.7 | 250 | 0 | 1.5 | 145 | 6 | 5 | 0 RP |

| Nielsen et al. 2007 | 120 | 29 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 46 | 36 | 2 pelvic outside template |

| 4 pulmonary | |||||||||

| 1 biochemical | |||||||||

| Neyer et al. 2007 | 136 | 68 | 261 | 5.1% | 4.1 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 6 pulmonary |

| 1 biochemical | |||||||||

| 1 RP outside template | |||||||||

| Albqami and Janetschek, 2005 | 103 | 62 | 217 | 2.9% | 3.6 | 144 | 26 | 26 | 1 RP outside template |

| 3 pulmonary | |||||||||

| 1 biochemical | |||||||||

For patients with pN0 disease following LRPLND, retroperitoneal recurrences are rare. Furthermore when a retroperitoneal recurrence does occur, it is often outside of the reported LRPLND template. This data supports that LRPLND is an effective procedure for staging the retroperitoneum. Unfortunately, the data with regard to its role as a therapeutic procedure is still lacking. In most contemporary series adjuvant chemotherapy continues to be given to patients with any nodal involvement at the time of LRPLND. Of the 122 node positive patients reported in the series listed in Table 1, 111 (91%) have received adjuvant chemotherapy. In the two series in which chemotherapy was not administered to node positive patients, none have recurred within the boundaries of the RPLND template. Skolarus et al. reported one patient in their series with pathologic stage IIA disease who is without evidence of disease 31.3 months following LRPLND [Skolarus et al. 2008]. Nielsen et al. reported on ten pathologic stage IIA patients who were observed without chemotherapy after LRPLND. Two (20%) patients recurred (1 biochemical, 1 pulmonary) following LRPLND and were salvaged with chemotherapy. The remaining 8 patients are without evidence of disease at a mean follow up of 37 months [Nielsen et al. 2007]. More recently Steiner et al. have reported their experience with bilateral nerve sparing LRPLND in 21 clinical stage I NSCGT patients, five (24%) of which were found to have pathologic stage IIA disease [Steiner et al. 2008]. None of the five patients were given adjuvant chemotherapy and all are without recurrence at follow-up intervals of 2–35 months. Additionally, no retroperitoneal recurrences were noted in patients who were pathologically confirmed stage I disease. Although the number of patients who did not receive chemotherapy in these three studies is small and the follow up is relatively short, the results are promising regarding the therapeutic role of LRPLND in experienced hands.

LRPLND for patients with clinical stage II NSGCTs

The data regarding the role of LRPLND for patients with clinical stage II NSGCTs either as a primary modality or in the post-chemotherapy is scant. There is limited data regarding the use of primary LRPLND in patients with clinical stage IIA disease and therefore no reasonable conclusions can be drawn. Several authors have reported on the use of LRPLND in the post-chemotherapy setting. Albqami and Janetschek have reported their experience with 59 patients with stage IIB or IIC disease that have undergone post-chemotherapy LRPLND [Albqami and Janetschek, 2005]. Impressively, they report no open conversions in this patient population, again highlighting the importance of patient selection and surgeon experience. Of the 43 patients with preoperative stage IIB disease with a mean follow up of 53 months, one experienced a recurrence 24 months postoperatively along the external iliac nodes, outside the original template. Maldonado-Valadez et al. have also demonstrated the feasibility of post-chemotherapy LRPLND in a small number of patients (n = 16), reporting no open conversions or blood transfusions [Maldonado-Valadez et al. 2007]. Viable tumors were found in threee (19%) patients, of which two received additional adjuvant chemotherapy. Of concern, two patients with viable tumor experienced a recurrence. The first was noted to have an enlarged renal hilar lymph node at his first 3 month postoperative follow up. This was managed with repeat LRPLND and the final histology revealed only necrosis. A second patient had a retroperitoneal recurrence 11 months postoperatively and ultimately died of his disease despite salvage chemotherapy. The two series discussed above are concerning from an oncologic perspective given the fact that a full bilateral RPLND was not performed, which is generally considered standard of care in the post-chemotherapy setting for NSGCT patients [Stephenson and Sheinfeld, 2004]. Although post-chemotherapy RPLND has been performed safely as detailed by the authors above, others have reported open conversion rates as high as 29% and 67% and overall complication rates >50% [Palese et al. 2002; Rassweiler et al. 1996]. Given the high potential for complications in post-chemotherapy patients, LRPLND should only be attempted in highly selected patients by surgeons with significant laparoscopic experience.

Keeping in line with the goals of open post-chemotherapy RPLND, Steiner et al. have performed bilateral nerve-sparing LRPLND on 19 post-chemotherapy patients with stage IIB disease [Steiner et al. 2008]. The authors found teratoma, necrosis/fibrosis, and active tumor in 4, 14 and 1 patient respectively. LRPLND was also performed in two patients with clinical stage IIA disease who did not undergo chemotherapy. No retroperitoneal recurrences were noted in either group at 17 months follow up.

Complications of LRPLND

Although LRPLND is a minimally invasive procedure with the intent of minimizing the morbidity of open surgery, it is not without complications even in experienced hands. There is a steep learning curve with this procedure, but when performed at high volume centers the open conversion and perioperative morbidity rates in contemporary series have been acceptable. The most common reason for conversion to an open procedure is uncontrollable bleeding and vascular injury is cited as the most common intraoperative complication [Kenney and Tuerk, 2008; Neyer et al. 2007; Abdel-Aziz et al. 2006; Bhayani et al. 2003]. In most contemporary series, the open conversion rate is < 5%, but conversions rates have been reported as high as 11.8% [Cresswell et al. 2008; Skolarus et al. 2008; Neyer et al. 2007; Nielsen et al. 2007; Albqami and Janetschek, 2005; Rassweiler et al. 2000]. In order to minimize open conversion rates and limit bleeding related morbidity (increased transfusion rates and increased LOS), surgeons performing LRPLND should be comfortable not only dissecting around major vascular structures, but also with laparoscopic hemostasis should the need arise. Familiarity with hemostasis maneuvers (eg. manipulation of pneumoperitoneum pressure, introducing a sponge laparoscopically, use of hemostatic agents) and laparoscopic suturing is critical to avoid excessive bleeding. Conversion to an open procedure should never be viewed as a failure and thus surgeons should be familiar with open RPLND as well. Injury to major abdominal viscera has also been reported, but appears to be a rare event [Kenney and Tuerk, 2008, Neyer et al. 2007]. Due to the potentially severe fibrotic reaction that can be found at the time of post-chemotherapy RPLND, it is not surprising that both open conversion and vascular injury rates are higher in this setting [Kenney and Tuerk, 2008; Palese et al. 2002 Rassweiler et al. 1996].

Postoperative complications have been reported at a rate of 9.4–25.7% in contemporary series [Cresswell et al. 2008; Skolarus et al. 2008; Neyer et al. 2007; Nielsen et al. 2007; Albqami and Janetschek, 2005]. Reported complications include chylous ascites, ileus, lymphocele, nerve injury, pulmonary embolus, C. difficile colitis, retroperitoneal hematoma and urinoma [Kenney and Tuerk, 2008]. Retrograde ejaculation is a potential long-term source of morbidity for patients undergoing both open and LRPLND. Fortunately the rates of retrograde ejaculation have been consistently low with the laparoscopic approach and range from 0–4.8% [Cresswell et al. 2008; Skolarus et al. 2008; Neyer et al. 2007; Nielsen et al. 2007; Albqami and Janetschek, 2005]. The incidence of retrograde ejaculation is higher in post-chemotherapy LRPLND patients, again due to dense fibrotic reaction which makes dissection and preservation of the nerves extremely challenging.

Although LRPLND is touted to decrease patient morbidity, very few reports exist using patient reported quality of life (QOL) data following treatment with LRPLND. Poulakis et al. have recently reported a comparison of patient reported QOL outcomes between LRPLND and open RPLND using validated QOL questionnaires [Poulakis et al. 2006]. The authors found statistically significant decreased analgesic requirements and time to resumption of oral intake in patients who underwent LRPLND. Additionally, LRPLND patients returned to their preoperative baseline QOL scores significantly faster than did the open cohort.

Conclusion

LRPLND has been demonstrated to be feasible and safe at large volume institutions with experienced laparoscopic surgeons. LRPLND was originally performed as a staging procedure in patients with NSGCTs but has evolved into a therapeutic operation with early reports demonstrating short hospital stays and minimal morbidity. Further studies in larger cohorts of patients with longer term follow up are required to define the exact role of LRPLND.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- Abdel-Aziz K.F., Anderson J.K., Svatek R., Marqulis V., Saqalowsky A.I., Cadeddu J.A. (2006) Laparoscopic and open retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ-cell testis tumors. J Endourol 20: 627–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albqami N., Janetschek G. (2005) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection in the management of clinical stage I and II testicular cancer. J Endourol 19: 683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniel J., Foster R.S., Gonin R., Messemer J.E., Donohue J.P., Einhorn L.H. (1995) Late relapse of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 13: 1170–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhayani S.B., Ong A., Oh W.K., Kantoff P.W., Kavoussi L.R. (2003) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer: a long-term update. Urology 62: 324–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver B.S., Sheinfeld J. (2005) Germ cell tumors of the testis. Ann Surg Oncol 12: 871–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo J.R., Haber G.P., Jelovsek J.E, Lane B., Novick A.C., Gill I.S. (2008) Seven years after laparoscopic radical nephrectomy: oncologic and renal functional outcomes. Urology 1: 1149–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell J., Scheitlin W., Grozen A., Lenz E., Teber D., Rassweiler J. (2008) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection combined with adjuvant chemotherapy for pathological stage II disease in nonseminomatous germ cell tumours: a 15-year experience. Br J Urol Int 102: 844–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerr A., Skinner E.C., Skinner D.G. (1993) Preservation of ejaculation through a modified retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in low stage testis cancer. J Urol 149: 1472–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue J.P., Zachary J.M., Maynard B.R. (1982) Distribution of nodal metastases in nonseminomatous testis cancer. J Urol 128: 315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue J.P., Foster R.S., Rowland R.G., Bihrle R., Jones J., Geier G. (1990) Nerve-sparing retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy with preservation of ejaculation. J Urol 144: 287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue J.P., Thornhill J.A., Foster R.S., Rowland R.G., Bihrle R. (1993) Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for clinical stage A testis cancer (1965 to 1989): modifications of technique and impact on ejaculation. J Urol 149: 237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggener S.E., Carver B.S., Sharp D.S., Motzer R.J., Bosl G.J., Sheinfeld J. (2007) Incidence of disease outside modified retroperitoneal lymph node dissection templates in clinical stage I or IIA nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. J Urol 177: 937–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A., Albers P., Hartmann M., Kliesch S., Kohrmann K.U., Krege S., et al. (2003) Complications of primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: experience of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. J Urol 169: 1710–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetschek G., Reissiql A., Peschel R., Hobisch A., Bartsch G. (1994) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous testicular tumor. Urology 44: 382–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney P.A., Tuerk I.A. (2008) Complications of laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular cancer. World J Urol 26: 561–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Valadez R., Schilling D., Anastasiadis A.G., Sturm W., Stenzl A., Corvin S. (2007) Post-chemotherapy laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection in testis cancer patients. J Endourol 21: 1501–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer M., Peschel R., Akkad T., Springer-Stohr B., Berger A., Bartsch G., et al. (2007) Long-term results of laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ-cell testicular cancer. J Endourol 21: 180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M.E., Lima G., Schaeffer E.M., Porter J., Cadeddu J.A., Tuerk I., et al. (2007) Oncologic efficacy of laparoscopic RPLND in treatment of clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. Urology 70: 1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palese M.A., Su L.M., Kavoussi L.R. (2002) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection after chemotherapy. Urology 60: 130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V.R., Palmer K.J., Coughlin G., Samavedi S. (2008) Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: perioperative outcomes of 1500 cases. J Endourol 22: 2299–2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulakis V., Skriapas K., De Vries R., Dillenburg W., Ferakis N., Witzsch U., et al. (2006) Quality of life after laparoscopic and open retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumor: a comparison study. Urology 68: 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani F., Sheinfeld J., Farivar-Mohseni H., Leon A., Rentzepis M.J., Reuter V.E., et al. (2001) Low-volume nodal metastases detected at retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for testicular cancer: pattern and prognostic factors for relapse. J Clin Oncol 19: 2020–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassweiler J.J., Seemann O., Henkel T.O., Stock C., Frede T., Alken P. (1996) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: indications and limitations. J Urol 156: 1108–1113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassweiler J.J., Frede T., Lenz E., Seemann O., Alken P. (2000) Long-term experience with laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in the management of low-stage testis cancer. Eur Urol 37: 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray B., Hajdu S.I., Whitmore Jr, W.F. (1974) Proceedings: distribution of retroperitoneal lymph node metastases in testicular germinal tumors. Cancer 33: 340–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie J.P. (1990) Clinical stage 1 testicular cancer: the role of modified retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. J Urol 144: 1160–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie J.P., Kantoff P.W. (1991) Is adjuvant chemotherapy necessary for patients with stage B1 testicular cancer? J Clin Oncol 9: 1393–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie J.P. (2005) Open retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. Can J Urol 1: 37–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinfeld J., Motzer R.J., Rabbani F., McKiernan J., Bajorin D., Bosl G.J. (2003) Incidence and clinical outcome of patients with teratoma in the retroperitoneum following primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stages I and IIA nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. J Urol 170: 1159–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolarus T.A., Bhayani S.B., Chiang H.C., Brandes S.B., Kibel A.S., Landman J., et al. (2008) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for low-stage testicular cancer. J Endourol 22: 1485–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H., Zangerl F., Stohr B., Granig T., Ho H., Bartsch G., et al. (2008) Results of bilateral nerve sparing laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. J Urol 180: 1348–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson A.J., Sheinfeld J. (2004) The role of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in the management of testicular cancer. Urol Oncol 22: 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson A.J., Sheinfeld J. (2005) Management of patients with low-stage nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 6: 367–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach L., Boedefeld E.A. (1987) Localization of solitary and multiple metastases in stage II nonseminomatous testis tumor as basis for a modified staging lymph node dissection in stage I. J Urol 138: 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield H.N. (1998) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for cancer of the testis. Urol Clin North Am 25: 469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Sheinfeld J., Motzer R.J. (1997) Adjuvant chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 6: 863–878 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]