Abstract

The shedding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) into saliva droplets plays a critical role in viral transmission. The source of high viral loads in saliva, however, remains elusive. Here we investigate the early target cells of infection in the entire array of respiratory tissues in Chinese macaques after intranasal inoculations with a single-cycle pseudotyped virus and a pathogenic SARS-CoV. We found that angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-positive (ACE2+) cells were widely distributed in the upper respiratory tract, and ACE2+ epithelial cells lining salivary gland ducts were the early target cells productively infected. Our findings also have implications for SARS-CoV early diagnosis and prevention.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a recently emerged human infectious disease caused by a zoonotic coronavirus (SARS-CoV) that has a mortality rate of approximately 10% (11, 20, 24, 30). Although it is known that SARS-CoV is transmitted via saliva droplets, the source of high viral loads (up to 6.38 × 108 copies/ml) in patients' saliva remains elusive, especially during the acute phase of viral replication (41). We hypothesized that viral replication in the upper respiratory tract may contribute to the rapid viral shedding into saliva droplets. To address this hypothesis, it is necessary to investigate SARS-CoV infection at the site of viral entry, including the identification of early target cells.

Our current understandings of the target cells for SARS-CoV are largely based on autopsy specimens of patients who died of SARS. Multiple cell types in the lower respiratory tract were found to be infected, including type I alveolar epithelium, macrophages, and putative CD34+ Oct-4+ stem/progenitor cells in human lungs (2, 7, 10, 13, 28, 29). These results, while very informative, do not address the question of which cell types support the initial seeding of infection in the upper respiratory tract. Since the SARS outbreak in humans has subsided and because many of the current scientific questions are difficult to address in humans, several animal models have been developed.

Animal models that have been used to study SARS-CoV infection include mice, hamsters, ferrets, cats, and nonhuman primates (cynomolgus macaques, rhesus macaques, common marmosets, and African green monkeys) (1, 12, 14, 22, 26, 27, 32, 33, 35). Although none of these animal models reproduce lethal SARS, most support SARS-CoV infection to some extent and therefore have contributed greatly to attempts to develop vaccines and therapeutics (1, 9, 14, 19, 43). We have recently demonstrated that rhesus angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the primary receptor of SARS-CoV, supports viral entry as efficiently as does its human homologue (3, 23). Moreover, Chinese-origin rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) experimentally infected with a pathogenic SARS-CoV developed lung damage similar to that seen in humans with SARS (31). The Chinese rhesus macaque model, therefore, offers us an opportunity to study the early target cells of SARS-CoV in the respiratory tract.

To allow careful examination of the initial targets of infection, we developed a single-cycle reporter virus pseudotyped with a functional (Opt9) or a nonfunctional [SΔ(422–463)] spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV (5, 45). As previously described by others and us, the commonly used pseudoviruses were generated by cotransfection of HEK293T cells with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-Luc+Env−Vpr− backbone and S-glycoprotein expression plasmids (18, 25, 45, 46). These pseudoviruses, however, are not feasible for monkey experiments due to host factors (e.g., Trim 5α) which restrict HIV-based pseudovirus in simian cells (38). We have, therefore, developed SIVmac-Luc+Env−Vpr− as the backbone vector, which we constructed by placing the luciferase gene in place of the viral nef gene (Fig. 1A) to generate the functional pseudovirus simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-OPT9 (4, 6). The nonfunctional envelope [SΔ(422–463)] was included to generate a control pseudovirus, SIV-SΔ(422–463) (45). Pseudoviral stocks were quantified by SIV p27 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and tested for their infectivity in HEK293T-human ACE2 (huACE2) cells or HEK293T cells transfected with Chinese macaque ACE2 (cmACE2) (3, 45). As shown in Fig. 1B, SIV-OPT9 pseudovirus infected efficiently both HEK293T-huACE2 cells and HEK293T-cmACE2 cells. As expected, the control SIV-SΔ(422–463) failed to infect either cell type (Fig. 1B). Moreover, cells incubated with SIV-OPT9 showed strong cytoplasmic expression of luciferase around 48 h postinfection (Fig. 1C), whereas no positive signals were found in cells incubated with SIV-SΔ(422–463) or in uninfected cells (Fig. 1C). These results confirmed that the detection of reporter luciferase expression is a specific indicator of SIV-OPT9 infection. Since luciferase expression peaks around 48 h postinfection both in vitro and in vivo, we chose this time point for our monkey studies (17).

Fig. 1.

Construction and characterization of single-cycle pseudoviruses SIV-OPT9 and SIV-SΔ(422–463). (A) Genomic organizations of SIVmac-Luc+Env−Vpr−, OPT9, and SΔ(422–4630) are shown. Pseudoviruses SIV-OPT9 and SIV-SΔ(422–463) were generated by cotransfection of HEK293T cells with SIVmac-Luc+Env−Vpr− and a full-length SARS-CoV Spike gene OPT9 or SΔ(422–463) (45). LTR, long terminal repeat; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter. (B) Entry assay of SIV-OPT9 and SIV-SΔ(422–463) pseudotyped viruses. Five nanograms (measured by p27) of each pseudovirus was used to infect transfected HEK293-huACE2 and HEK293-cmACE2 cells. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h postinfection using a commercial kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Triplicates were tested in each experiment. The average values and standard error bars are presented. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results being obtained each time. (C) Immunohistological detection of luciferase expression in pseudovirus-infected cells. Both HEK293T-huACE2 and HEK293T-cmACE2 cells infected with SIV-OPT9 show a strong cytoplasmic expression of luciferase (panels 1 and 4), whereas no positive signals were found in cells incubated with SIV-SΔ(422–463) (panels 2 and 5) and in uninfected cells (panels 3 and 6).

To identify the early target cells of SARS-CoV in vivo, seven Chinese macaques were included in this experiment, and all were inoculated via the intranasal route: three with pseudovirus SIV-OPT9, two with SIV-SΔ(422–463), and two with cell culture medium. A high dose of each pseudovirus (approximately 400 ng p27/ml, which contains about 109 RNA copies of virus) was administered to each animal. Animals were sacrificed 48 h after inoculation, and tissue specimens were collected for analysis from throughout the respiratory tract, including the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, epiglottis, larynx, trachea, left bronchus, right bronchus, and lungs (left and right cranial, middle, and caudal lobes and right accessory lobe). The animal protocols were approved by our institutional animal welfare committee.

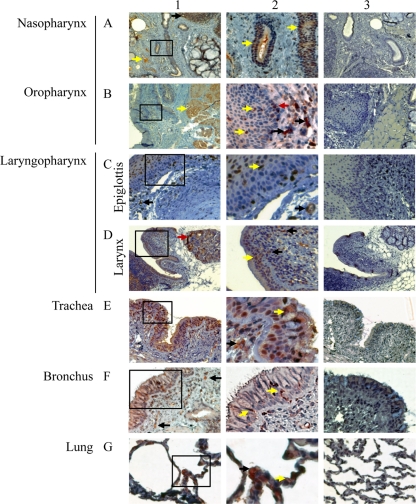

It is known that ACE2 is the functional receptor of SARS-CoV and plays a crucial role in SARS lung pathogenesis (21, 23). Although ACE2 mRNA and protein have been found in multiple human organs, the protein distribution throughout the respiratory tract has not been comprehensively investigated (15, 16). To address this question and to identify the possible route of viral infection, we investigated the localization and distribution of ACE2+ cells in the entire respiratory tract of Chinese rhesus macaques. By immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, ACE2+ cells were found to be abundantly present throughout the respiratory tract (Fig. 2, panels 1 and 2). Similar to the human situation, numerous ACE2-positive cells were observed in the epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract and in the lamina propria, as well as the cells morphologically compatible with salivary gland duct epithelium. Control rabbit antibodies did not result in any positive signals in consecutive tissue sections (Fig. 2, panel 3). The finding of ACE2+ cells in salivary gland duct epithelium has not been described previously, probably due to the lack of examination of the relevant tissues (15). These findings suggest that target cells for SARS-CoV may be more widespread in the respiratory tract than previously recognized, particularly early in infection (15).

Fig. 2.

Detection of ACE2+ cells by immunohistochemistry at multiple levels of the respiratory tracts of rhesus macaques. Positive labeling for ACE2 was found at all levels of the respiratory tract. For each level examined, a low-magnification overview is shown in panel 1 with a higher magnification of the boxed area in panel 1 shown in panel 2. Panel 3 shows the same tissue immunolabeled with control rabbit serum. The magnifications of each image are as follows: ×40 (A1), ×100 (A3, B1, B3, C1, C3, D1, D3, E1, and E3), ×200 (A2, F1, F3, G1, and G3), and ×400 (B2, C2, D2, E2, F2, and G2). In nasopharynx (A) and oropharynx (B), ACE2+ cells were identified in lymphatic nodules (black arrow, A1), vascular endothelium (yellow arrow, A1), the epithelium of salivary gland ducts (yellow arrow, A2), some muscle cells (yellow arrow, B1), epithelium lining (yellow arrows, B2), lamina propria (black arrows, B2), and basal layer of the epidermis (red arrow, B2). In epiglottis (C), ACE2+ cells were found in lamina propria (black arrow, panel 1), the epithelial lining (yellow arrow, panel 2), and capillaries (black arrow, panel 2). In larynx (D), ACE2+ cells were observed in glands (red arrow, panel 1), the epithelial lining (yellow arrow, panel 2), and lamina propria (black arrows, panel 2). In trachea (E), numerous ACE2+ cells were found in the epithelial lining (yellow arrow, panel 2), and lamina propria (black arrow, panel 2). In bronchus (F), many ACE2+ cells were identified in lamina propria (black arrows, panel 1) and in the epithelial lining (yellow arrows, panel 2). In lungs (G), ACE2+ cells were observed on type I pneumocytes (yellow arrow, panel 2) and type II pneumocytes (black arrow, panel 2).

To determine early target cells of SARS-CoV, we used a triple immunofluorescence staining technique to detect the luciferase protein (Luc+) and various cell-type-specific markers. Infected cells were identified in all three macaques (3/3) who received SIV-OPT9. In contrast, positive cells were not identified in any tissues of the four control macaques (4/4) who received either SIV-SΔ(422–463) or placebo. Luciferase signals were not detected in ACE2+ cells in epithelial layers of the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, epiglottis, larynx, and trachea. However, two of three SIV-OPT9-infected macaques displayed many infected cells in the epithelial layers of the salivary gland ducts in laryngopharynx (Fig. 3A). Positive cells were not found in other tissue sections examined. By testing various cell surface markers, these positive cells appeared to be Luc+ ACE2+ cytokeratin+ (Fig. 3A). Infected cells appeared to have weaker ACE2 staining (Fig. 3A, panel 2b), which was probably due to infection-induced partial ACE2 downregulation (21). To confirm this finding, in situ hybridization (ISH) was performed on all tissue sections to detect SIV genome with digoxigenin-11-dUTP-labeled RNA probe as previously described (42). Consistent with the results of the immunofluorescence microscopy data, labeled cells were found almost exclusively in the epithelium of the salivary gland ducts in the laryngopharynx (Fig. 3C). We did not detect positive cells in the laryngopharynx of the third monkey who received SIV-OPT9; however, the tissues collected were lacking salivary gland ducts. Interestingly, this animal displayed cytoplasmic staining of luciferase in sections of 3 lobes of the lungs (right cranial lobe, middle lobe, and left caudal lobe). We found that most of the Luc+ cells also were ACE2+ in the lungs with colocalization of cytokeratin on some of the cells (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the pulmonary epithelium is also a major early target of the virus. This finding is consistent with previous studies on human fatal cases (13, 28, 29, 39, 40, 44).

Fig. 3.

ACE2+ epithelial cells lining salivary gland ducts are early target cells of SARS-CoV infection. (A and B) Triple immunofluorescence labeling of luciferase (green as indicated by yellow arrows in A1 and B1), ACE2 (red in A1, A2b, A3b, B2a, and B3), cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) (red in A2a, A3a, and B2c), and cell nuclei (blue) on frozen sections of the laryngopharynx (A) and lung (B), respectively. The magnifications of each image are as follows: ×40 (A1 and B1) and ×400 (A2a, A2b, A3a, A3b, and A3c). The numbered insets correspond to the enlarged images in panels A and B. The triple labels involved a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antiluciferase antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Gilbertsville, PA), a rabbit anti-human ACE2 antibody or control rabbit serum, and a mouse anti-human cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) or control mouse serum (DakoCytomation, Inc., Carpinteria, CA). The secondary antibodies used to detect ACE2 or AE1/AE3 included an Alexa 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody or an Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR). Triple-label deconvolved images of the same tissue sections were collected using a DeltaVision deconvolution microscope (Applied Precision, Mercer Island, WA). Luciferase labeling was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate filters, as depicted in green (A and B). ACE2 was detected with the Alexa Fluor 568 filter as depicted in red (A2b, A3b, B2a, and B3). Cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) was detected with the Cy5 filter as depicted in red (A2a, A3a, and B2c). Hoechst-stained nuclei were detected with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole filter as depicted in blue (A and B). Sections from control animals or stained with control serum show no staining of luciferase labeling (B3). (C) ISH for the detection of SIV-OPT9-infected cells (panel 1). Numerous positive cells with blue-black labeling are present in the ductal epithelium (magnification, ×200; indicated by red arrows) using a method previously described (42). Control sections show no staining (panel 2).

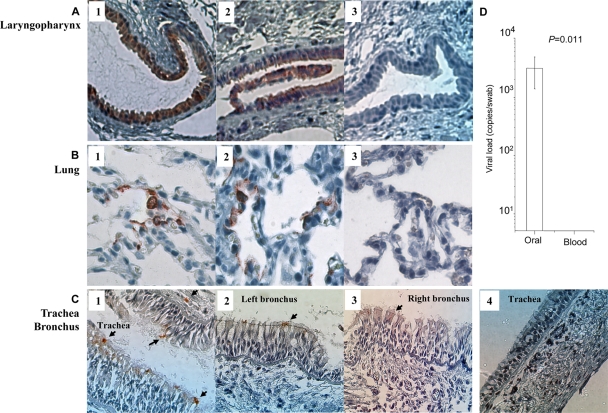

Our results are significant for understanding early events of SARS-CoV infection. However, the use of SIV-based pseudovirus can be a limitation of the study. To address this issue, another four Chinese macaques were challenged with a live pathogenic SARS-CoV as previously described (5). Tissue sections of laryngopharynx, trachea, left bronchus, right bronchus, and lung were stained with a commercial rabbit polyclonal antibody against SARS-CoV N protein 48 h post-viral challenge. The reason that we chose 48 h was mainly based on the natural course of SARS-CoV infection in Chinese macaques. We and others previously showed that it takes 48 h to easily detect SARS-CoV proteins (31), which is consistent with other animal model studies (8, 34, 36, 37). Moreover, this time point was chosen to match the 48-h time point used with the pseudotyped virus to show that the results were not an artifact of the construct. Like SIV-OPT9-infected animals, epithelial cells of the salivary gland ducts and lungs were infected by SARS-CoV in three (3/4; Rh0505, Rh0506, and Rh0507) and two (2/4; Rh0506 and Rh0508) of the four macaques, respectively (Fig. 4A and B). The tissue sections collected from the fourth monkey were lacking salivary gland ducts. Moreover, a few sporadic positive signals were found in the epithelial layers of the trachea and bronchus in one of four infected animals (1/4; Rh0505 [Fig. 4C]), which was in contrast to a large number of ACE2+ cells identified at these locations (Fig. 2E and F). This finding suggested that these sites were not yet significantly infected by SARS-CoV, probably due to the resistance of epithelial and mucus barriers at the time of examination. Importantly, SARS-CoV was readily detected in oral swabs but not in the blood of each of these infected macaques (4/4) on day 2 after intranasal challenges (Fig. 4D). These data are consistent with a previous study in humans where a larger amount of SARS-CoV RNA was found in saliva from all specimens of 17 SARS patients, including four patients before the development of lung lesions (41). The finding of viral loads in oral swabs from 4/4 animals in comparison to infected lungs in 2/4 macaques would likely suggest a critical role of viral production in upper respiratory sites, including salivary gland ducts, early in infection.

Fig. 4.

(A to C) Immunohistochemical staining of SARS-CoV N protein (red labeling) in tissue sections. These sections were derived from laryngopharynx (A1 to A3), lung (B1 to B3), trachea (C1 and C4), left bronchus (C2), and right bronchus (C3) of four infected macaques or control animals. They were stained with a rabbit anti-N protein antibody (eEnzyme, Montgomery Village, MD) as the first antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody as the second antibody. Epithelial cells of the salivary gland ducts (A1, Rh0506; A2, Rh0507) and lung (B1, Rh0506; B2, Rh0508) were readily infected (red labeling; magnification, ×200). Sporadic N protein-positive signals were found in the top epithelial layers of trachea and bronchus of one infected animal (Rh0505, C1 to C3, indicated by arrows). Tissues in panels A3, B3, and C4 were from the control animal Rh0514. (D) Viral loads of SARS-CoV in oral swabs of four infected macaques compared with their blood samples 48 h post-viral challenge. The mean values of four infected macaques are shown with standard error bars (the Student t test).

Our data, therefore, suggest that ACE2+/cytokeratin+ cells lining salivary gland ducts are early target cells of SARS-CoV and a likely source of the virions found in patients' saliva droplets, especially early in infection. Our findings, however, do not exclude the possibility that saliva virions might also come from other sources (e.g., respiratory secretions), especially later in infection. It remains to be further studied how many virions produced in trachea, bronchus, lungs, or other tissues would contribute to the saliva viral load. Moreover, a serial time point study would be necessary to further investigate the impact of upper respiratory tract infection on SARS-CoV transmission and pathogenesis.

In conclusion, we report here the distribution of ACE2+ cells in the respiratory tract of Chinese rhesus macaques, which mimics the human situation and extends those observations to more proximal tissues of the respiratory tract than have been examined in humans. Moreover, we have developed a safe pseudoviral system to study the early target cells of SARS-CoV in monkeys. We demonstrated for the first time that ACE2+/cytokeratin+ epithelial cells of salivary gland ducts in the upper respiratory tract are early targets of SARS-CoV infection in addition to other cells such as ACE2+/cytokeratin+ pneumocytes in lungs. This finding was confirmed by data generated using a live pathogenic SARS-CoV in Chinese rhesus macaques. Our findings provide evidence that salivary gland epithelial cells can be infected in vivo soon after infection. These infected cells could be a significant source of virus in saliva, particularly early in infection. This observation has significant implications for understanding SARS-CoV respiratory transmission, which is critical for the development of effective strategies for diagnosis, prevention, and therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Farzan for HEK293T-huACE2 cells, N. Landau for providing the molecular clones of HIV-Luc+Env−Vpr−, and D. D. Ho and K. Y. Yuen for scientific discussions.

We also thank the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (RO1 HL080211-02 to Z.C.), the TNPRC base grant RR00164, and the UDF/LKS grants of the University of Hong Kong to its AIDS Institute for financial support.

We declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bukreyev A., et al. 2004. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet 363:2122–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Y., et al. 2007. A novel subset of putative stem/progenitor CD34+Oct-4+ cells is the major target for SARS coronavirus in human lung. J. Exp. Med. 204:2529–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen Y., et al. 2008. Rhesus angiotensin converting enzyme 2 supports entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Chinese macaques. Virology 381:89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Z., Gettie A., Ho D. D., Marx P. A. 1998. Primary SIVsm isolates use the CCR5 coreceptor from sooty mangabeys naturally infected in west Africa: a comparison of coreceptor usage of primary SIVsm, HIV-2, and SIVmac. Virology 246:113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen Z., et al. 2005. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region. J. Virol. 79:2678–2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Z., Zhou P., Ho D. D., Landau N. R., Marx P. A. 1997. Genetically divergent strains of simian immunodeficiency virus use CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry. J. Virol. 71:2705–2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chow K. C., Hsiao C. H., Lin T. Y., Chen C. L., Chiou S. H. 2004. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus in pneumocytes of the lung. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 121:574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chu Y. K., et al. 2008. The SARS-CoV ferret model in an infection-challenge study. Virology 374:151–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Darnell M. E., et al. 2007. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in vaccinated ferrets. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1329–1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ding Y., et al. 2004. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J. Pathol. 203:622–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drosten C., et al. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1967–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenough T. C., et al. 2005. Pneumonitis and multi-organ system disease in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. Am. J. Pathol. 167:455–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gu J., et al. 2005. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J. Exp. Med. 202:415–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haagmans B. L., et al. 2004. Pegylated interferon-alpha protects type 1 pneumocytes against SARS coronavirus infection in macaques. Nat. Med. 10:290–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamming I., et al. 2004. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 203:631–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harmer D., Gilbert M., Borman R., Clark K. L. 2002. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 532:107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holt C. E., Garlick N., Cornel E. 1990. Lipofection of cDNAs in the embryonic vertebrate central nervous system. Neuron 4:203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang Y., Yang Z. Y., Kong W. P., Nabel G. J. 2004. Generation of synthetic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pseudoparticles: implications for assembly and vaccine production. J. Virol. 78:12557–12565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishii K., et al. 2009. Neutralizing antibody against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-coronavirus spike is highly effective for the protection of mice in the murine SARS model. Microbiol. Immunol. 53:75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ksiazek T. G., et al. 2003. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1953–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuba K., et al. 2005. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 11:875–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lawler J. V., et al. 2006. Cynomolgus macaque as an animal model for severe acute respiratory syndrome. PLoS Med. 3:e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li W., et al. 2003. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426:450–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li W., et al. 2005. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310:676–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu L., et al. 2007. Natural mutations in the receptor binding domain of spike glycoprotein determine the reactivity of cross-neutralization between palm civet coronavirus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 81:4694–4700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martina B. E., et al. 2003. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature 425:915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McAuliffe J., et al. 2004. Replication of SARS coronavirus administered into the respiratory tract of African Green, rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys. Virology 330:8–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakajima N., et al. 2003. SARS coronavirus-infected cells in lung detected by new in situ hybridization technique. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 56:139–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicholls J. M., et al. 2006. Time course and cellular localization of SARS-CoV nucleoprotein and RNA in lungs from fatal cases of SARS. PLoS Med. 3:e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peiris J. S., et al. 2003. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361:1319–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qin C., et al. 2005. An animal model of SARS produced by infection of Macaca mulatta with SARS coronavirus. J. Pathol. 206:251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roberts A., et al. 2005. Aged BALB/c mice as a model for increased severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome in elderly humans. J. Virol. 79:5833–5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roberts A., et al. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of golden Syrian hamsters. J. Virol. 79:503–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rockx B., et al. 2009. Early upregulation of acute respiratory distress syndrome-associated cytokines promotes lethal disease in an aged-mouse model of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 83:7062–7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rowe T., et al. 2004. Macaque model for severe acute respiratory syndrome. J. Virol. 78:11401–11404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sheahan T., et al. 2008. MyD88 is required for protection from lethal infection with a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smits S. L., et al. 2010. Exacerbated innate host response to SARS-CoV in aged non-human primates. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stremlau M., et al. 2004. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427:848–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. To K. F., et al. 2004. Tissue and cellular tropism of the coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome: an in-situ hybridization study of fatal cases. J. Pathol. 202:157–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H., Rao S., Jiang C. 2007. Molecular pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Microbes Infect. 9:119–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang W. K., et al. 2004. Detection of SARS-associated coronavirus in throat wash and saliva in early diagnosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1213–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williams K. C., et al. 2001. Perivascular macrophages are the primary cell type productively infected by simian immunodeficiency virus in the brains of macaques: implications for the neuropathogenesis of AIDS. J. Exp. Med. 193:905–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang Z. Y., et al. 2004. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature 428:561–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye J., et al. 2007. Molecular pathology in the lungs of severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Am. J. Pathol. 170:538–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yi C. E., Ba L., Zhang L., Ho D. D., Chen Z. 2005. Single amino acid substitutions in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein determine viral entry and immunogenicity of a major neutralizing domain. J. Virol. 79:11638–11646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang L., et al. 2006. Antibody responses against SARS coronavirus are correlated with disease outcome of infected individuals. J. Med. Virol. 78:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]