Abstract

The hemagglutinin (HA) envelope protein of influenza virus mediates viral entry through membrane fusion in the acidic environment of the endosome. Crystal structures of HA in pre- and postfusion states have laid the foundation for proposals for a general fusion mechanism for viral envelope proteins. The large-scale conformational rearrangement of HA at low pH is triggered by a loop-to-helix transition of an interhelical loop (B loop) within the fusion domain and is often referred to as the “spring-loaded” mechanism. Although the receptor-binding HA1 subunit is believed to act as a “clamp” to keep the B loop in its metastable prefusion state at neutral pH, the “pH sensors” that are responsible for the clamp release and the ensuing structural transitions have remained elusive. Here we identify a mutation in the HA2 fusion domain from the influenza virus H2 subtype that stabilizes the HA trimer in a prefusion-like state at and below fusogenic pH. Crystal structures of this putative early intermediate state reveal reorganization of ionic interactions at the HA1-HA2 interface at acidic pH and deformation of the HA1 membrane-distal domain. Along with neutralization of glutamate residues on the B loop, these changes cause a rotation of the B loop and solvent exposure of conserved phenylalanines, which are key residues at the trimer interface of the postfusion structure. Thus, our study reveals the possible initial structural event that leads to release of the B loop from its prefusion conformation, which is aided by unexpected structural changes within the membrane-distal HA1 domain at low pH.

INTRODUCTION

Enveloped viruses enter cells through fusion of their viral membrane with a host cell membrane. This fusion process is thermodynamically favorable but kinetically very slow and is facilitated by the fusion machinery embedded within the viral envelope glycoproteins (11). Although they are structurally diverse and are triggered by different stimuli (low pH, receptor and coreceptor binding), viral envelope proteins appear to share a common mechanism for membrane fusion (22, 46). Upon activation, these envelope proteins undergo large-scale conformational changes and usually insert a previously sequestered, hydrophobic “fusion peptide” into the target membrane. The newly formed “extended intermediate” (prehairpin) quickly folds back into a conformation termed a “trimer of hairpins” that brings the now host-cell-embedded fusion peptide into closer proximity to the viral membrane (38).

Depending on the structural characteristics of the postfusion state (“trimer of hairpins”), viral fusion proteins have been categorized into three classes (45): class I (prominent central α-helical coiled coil), including influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA), paramyxovirus fusion protein F, and HIV envelope protein; class II (mainly β-sheets), including dengue virus protein E and Semliki Forest virus E1; and class III (combination of a central α-helical coiled-coil and β-structures), such as vesicular stomatitis virus protein G and baculovirus fusion protein gp64. In recent years, crystal structures of representative ectodomains of each class of these viral envelope proteins have been determined in both pre- and postfusion states, uncovering the diverse variation in fusion mechanisms employed by different viruses (45, 46).

Influenza virus hemagglutinin is by far the best-characterized viral fusion protein. Its prefusion conformation was determined in 1981, the earliest for all viral glycoprotein antigens (48). The HA ectodomain is a homotrimer, with each protomer containing two polypeptides, HA1 and HA2, generated from a single nascent peptide chain through protease cleavage. Each HA trimer comprises a large membrane-distal, globular domain that binds to glycan receptors on host cells and an elongated membrane-proximal domain (stem region) dominated by intertwined and interconnecting α-helices (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The membrane-distal domain is formed only by HA1 and can be divided roughly into receptor-binding (furthest from the viral membrane) and vestigial esterase subdomains. The stem region is the main component of the HA fusion machinery and is comprised of HA2 (F fusion subdomain) and the N- and C-terminal segments of HA1 (F′ fusion subdomain) (36, 37).

The connecting loop between the antiparallel helices of HA2, the B loop, has a high propensity for a helical conformation (44) and transforms itself into part of a long α-helix in the postfusion HA (6, 8). This loop-to-helix transition enables extension of the central coiled coil and facilitates relocation of the fusion peptide toward the target membrane (19, 33). This B loop in the prefusion state is then trapped in a metastable conformation during protein expression and transport via the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi compartment to the cell surface, since recombinant HA2 by itself spontaneously folds into the postfusion conformation (7, 10). The molecular mechanism for release of the B loop from its metastable state is still unclear, although some rearrangement of HA1 is apparently required (2, 18, 23).

Similarly, little is known about the key residues that are thought to be protonated at low pH to initiate the fusion-related conformational changes. Protons are the sole signal needed to elicit HA fusion activity. Many mutations affecting the pH of fusion have been mapped throughout the HA trimer, most notably at subunit-subunit and domain-domain interfaces (13, 34, 42). Yet identifying the molecular identities of the “pH sensors” in HA has been a tremendous challenge, as for other pH-mediated viral fusion proteins (21). Many residues could have pKas in the pH range of 5 to 6 and thus serve as potential candidates for the pH sensor, including histidines, glutamates, and aspartates. Redundancy of ionic interactions, charge reversal mutations, and switching of salt bridges throughout evolution further complicate detailed characterization by traditional sequence-based analysis and mutagenesis studies. Structural study of fusion intermediates is equally difficult given their transient nature. Intermediates of HA fusion have been probed using indirect methods of antibody binding, limited proteolysis, and cryo-electron microscopy, etc. (5, 25, 26, 32, 47). These studies mapped out the general principles of hemagglutinin fusion, but further appreciation of the intricacies of the fusion mechanism has awaited structural views of fusion intermediates at the atomic level.

Here we utilized a stabilizing mutant of H2 HA (A/Japan/305/57) for investigation of pH-dependent structural transitions related to the “unclamping” of the B loop from its prefusion state. An arginine-to-histidine mutation of residue 106 (numbering based on the H3 HA structure [48]) in HA2, located more than 20 Å from the B loop (see Fig. 1A), is sufficient to retain H2 HA in a near-prefusion conformation even under fusogenic conditions of pH 5 to 6. Structural comparison of mutant H2-HA2R106H at neutral and fusogenic pHs reveals the conformational changes in the B loop and neighboring structural elements that precede the irreversible loop-to-helix transition. Analysis of this mutant in the context of structures of the pre- and postfusion states has led to an appreciation that a more extensive group of ionic residues is responsible for the structural changes during the early fusion steps. The HA1 membrane-distal domain, commonly believed to remain structurally unchanged during fusion, undergoes reversible conformational changes that assist in the “unclamping” of the B loop.

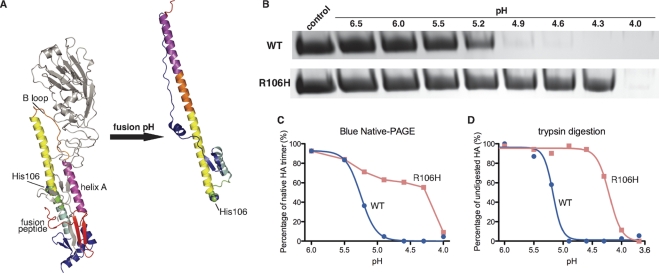

Fig. 1.

HA2R106H mutation in the HA2 subunit of H2 HA stabilizes the near-prefusion structure at fusogenic pH. (A) Residue 106 is located in the midsection of the HA2 central helix and is close to the fusion peptide cavity in the prefusion structure (left side). In the postfusion structure (right side) (homology model based on H3 postfusion structure, PDB 1QU1 [10]), the peptide segment near residue 106 refolds into an unstructured loop and allows the end of the original long C helix to fold back on itself in the prehairpin intermediate. The HA1 subunit is shown in gray. The HA2 subunit is color coded by segments from the N to the C terminus (red, magenta, orange, yellow, green, cyan, and blue), based on the analysis of its pre- and postfusion structures (6). (B to D) At the fusogenic pH for wild-type H2 HA, H2-HA2R106H maintains a conformation resembling the prefusion state. Contrary to results for wild-type H2 treated at a similar pH, it migrates similarly to untreated HA in blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (B and C) and resists trypsin digestion (D) (see also Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material for details).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification of H2 HA2R106 mutant.

The HA2R106H mutant of H2 HA was generated using the polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) cloning method (24) and verified by DNA sequencing. The ectodomain was expressed and purified as described previously (50).

Crystallization and structural determination of H2-HA2R106H at pH 8.1.

Purified HA was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0, and crystallized by mixing with an equal volume (2 μl each) of precipitant solution using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 22.5°C. The precipitant in the reservoir contained 28% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3000 and 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.1. Crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen after brief soaking in reservoir solution plus 15% ethylene glycol. Data sets were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) beamline 9-2 and processed with the HKL2000 software program (31). The crystal structure of H2-HA2R106H at pH 8.1 was solved by molecular replacement with the Phaser software program (28) in the CCP4 package (12) using a protomer of H2 HA (3KU3, A/Japan/305/1957) (50). The structure was adjusted using the COOT software program (16) and refined with the REFMAC program (30). Statistics for data collection and structure refinement are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter or category | Value or identifier for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2-HA2R106H |

H2-HA2R106H (reneutralized) | H2-HA1 | ||

| Neutral pH | Low pH | |||

| Data collection statistics | ||||

| Crystallization pH | 8.1 | 5.3 | 9.0 | 8.1 |

| Beamline | SSRL 9–2 | SSRL 11–1 | SSRL 9–2 | APS GM/CA–CAT 23ID-B |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.91837 | 0.97939 | 0.97915 | 0.97958 |

| Space group | P63 | P21 | P63 | P1 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å or °) | a = b = 70.3 | a = 68.0; b = 240.1 | a = b = 70.5 | a = 38.6; b = 62.0 |

| c = 237.3 | c = 70.3 | c = 237.5 | c = 66.1 | |

| α = β = 90.0 | α = 90.0, β = 116.5 | α = β = 90.0 | α = 64.4; β = 80.1 | |

| γ = 120.0 | γ = 90.0 | γ = 120.0 | γ = 72.2 | |

| Resolution (Å)a | 35–1.97 (2.04–1.97) | 45–2.90 (3.00–2.90) | 40–2.10 (2.18–2.10) | 50–1.65 (1.71–1.65) |

| No. of: | ||||

| Observations | 375,848 | 133,153 | 292,570 | 114,551 |

| Unique reflectionsa | 46,401 (4,608) | 39,294 (2,066) | 37,509 (3,141) | 60,290 (5,312) |

| % completenessa | 99.7 (99.2) | 88.4 (46.9) | 97.6 (81.8) | 94.8 (83.8) |

| 〈I/σI〉a | 24.7 (3.6) | 14.4 (2.6) | 18.3 (1.5) | 11.5 (2.9) |

| Rsymb (%)a,b | 6.5 (43.2) | 7.8 (32.2) | 8.4 (51.4) | 5.3 (24.4) |

| Zac | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2d |

| Refinement statistics | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 35.0–1.97 | 43.4–2.90 | 33.0–2.10 | 36.7–1.65 |

| Reflections (total) | 44,030 | 39,217 | 35,567 | 60,214 |

| Reflections (test) | 2,346 | 1,991 | 1,874 | 3,056 |

| Rcryst (%)e | 18.3 | 22.3 | 19.1 | 20.1 |

| Rfree (%)f | 22.5 | 28.9 | 23.5 | 23.4 |

| Avg B value (Å2) | 35.6 | 87.8 | 40.9 | 26.9 |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 32.0 | 63.7 | 41.9 | 22.6 |

| No. of: | ||||

| Protein atoms | 3,929 | 11,766 | 3,921 | 3,473 |

| Carbohydrate atoms | 56 | 226 | 56 | 58 |

| Water molecules | 552 | 63 | 434 | 616 |

| RMSD from ideal geometry | ||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.68 | 0.90 | 1.34 | 1.12 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)g | ||||

| Favored | 97.0 | 87.9 | 97.0 | 96.7 |

| Outliers | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| PDB ID | 3QQB | 3QQO | 3QQE | 3QQI |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell.

Rsym = Σhkl|〈I i−〉 |/Σhkl Ii, where Ii is the scaled intensity of the ith measurement and 〈Ii〉 is the average intensity for that reflection.

Za is the number of HA protomers per crystallographic asymmetric unit.

Here, Za is the number of HA1 monomers per crystallographic asymmetric unit.

Rcryst = Σhkl|Fo − Fc|/Σhkl|Fo| × 100.

Rfree was calculated as for Rcryst but on a test set comprising 5% of the data excluded from refinement.

Calculated using Molprobity (14).

Crystallization and structural determination of H2-HA2R106H at pH 5.3.

Purified HA was crystallized by mixing with an equal volume (1 μl each) of precipitant solution using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 22.5°C. The precipitant in the reservoir contained 16% PEG 3000 and 0.1 M citric acid, pH 5.3. Crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen after a brief soak in reservoir solution plus 15% ethylene glycol. Data sets were collected at SSRL beamline 11-1 and processed with HKL2000 (31). The diffraction data were indexed in space group P21. The crystal structure of H2-HA2R106H at pH 5.3 was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (28) in the CCP4 package (12) using a protomer of H2 HA (3KU3, A/Japan/305/1957) (50). Each asymmetric unit contains three HA protomers (one HA trimer). The structure was adjusted using COOT (16) and refined with REFMAC (30) and PHENIX (1). Statistics for data collection and structure refinement are presented in Table 1.

Crystallization and structural determination of reneutralized H2-HA2R106H at pH 9.

Purified HA was incubated in 0.17 M sodium acetate, pH 5, at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, the reaction mixture was neutralized to pH 8 using 1 M Tris and subsequently purified through a Superdex200 gel filtration column using a buffer of 20 mM Tris, pH 8, and 50 mM NaCl. The purified protein was concentrated to 11 mg/ml and crystallized by mixing with an equal volume (2 μl each) of precipitant solution using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 22.5°C. The precipitant in the reservoir contained 24% PEG 3000 and 0.1 M Tris, pH 9. Crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen after brief soaking in reservoir solution plus 15% ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant. Data sets were collected at SSRL beamline 11-1 and processed with HKL2000 (31). The crystal structure of reneutralized H2-HA2R106H at pH 9 was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (28) using a protomer of H2 HA (3KU3, A/Japan/305/1957) (50). The structure was adjusted using COOT (16) and refined with REFMAC (30). Statistics for data collection and structure refinement are presented in Table 1.

Expression, crystallization, and structural determination of H2-HA1.

The gene corresponding to the membrane-distal domain of H2 HA (HA1 43–309) was inserted into a baculovirus expression vector modified from pAcGP67A (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) (40) and expressed as described previously (50). The construct contains an N-terminal signal sequence for secretion, HA1 residues 43 to 309 (H3 numbering), a thrombin cleavage site, a trimerization foldon sequence, and a His6 tag for purification.

The expressed HA1 was first purified though a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity column and a Mono Q ion exchange column. It was then digested using proteinase K (protein/enzyme ratio is 1,000:1) at room temperature for 1 h. Digested product was purified through a gel filtration column and concentrated to 13.3 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0. It was crystallized by mixing with an equal volume (0.5 μl each) of precipitant solution using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 22.5°C. The precipitant in the reservoir contained 1.25 M sodium citrate and 0.1 M HEPES, pH 8.1. Crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen after brief soaking in reservoir solution plus 15% ethylene glycol. Data sets were collected at Advanced Photon Source (APS) beamline 23ID-B and processed with HKL2000 (31). The crystal structure of HA1 was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (28) using the membrane-distal domain of H2 HA (3KU3, A/Japan/305/1957) (50). The structure was adjusted using COOT (16) and refined with REFMAC (30) and BUSTER (4) software. Residues 55 to 268 of HA1 were built in the final structure, which includes the receptor-binding and vestigial esterase subdomains of HA1. Statistics for data collection and structure refinement are presented in Table 1.

BN-PAGE gel shift assay.

A blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) gel shift assay was carried out on NativePAGE Novex Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). In general, 10- to 20-μg HA samples were mixed with 1 M citrate buffer and 10% β-d-maltoside (final concentrations, 0.1 M citric acid, 1% β-d-maltoside). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h unless specified otherwise. The samples were then analyzed on the gel using procedures suggested by the manufacturer. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue and analyzed with the VersaDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad). Protein bands migrating as did the control HA sample were considered to be in near-prefusion conformation. Band intensities and areas were measured, and the approximate amount of protein in each band was calculated by average intensity multiplied by area. Data were plotted in the GraphPad Prism software program.

Limited proteolysis by trypsin.

Ten-microgram HA samples were acid treated, as described for the gel shift assay, and then neutralized with 1 M Tris, pH 8, and digested with tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone, L-1-tosylamide-2-phenylmethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (New England Biolabs). The mixtures were incubated at 22°C for 20 h before being analyzed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue and analyzed using the VersaDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad). The amount of undigested HA was calculated according to the measured average band intensity and band area. Data were plotted in GraphPad Prism.

Syncytium fusion assay.

A cell-based fusion assay was carried out as previously described by Reed et al. (35). Monolayers of Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) grown in 12-well plates were transiently transfected with 0.4 μg of pCAGGS H2 HA DNA using the Lipofectamine LTX expression system with Plus reagent (Invitrogen). After 4 h incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, growth medium was changed to 1 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The transfected Vero cells were incubated for another 16 h at 37°C. The cells were then treated with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen) for 10 min at room temperature and incubated in 1 ml DMEM containing FBS for 15 min at 37°C. Membrane fusion was induced by incubating the cell monolayers with 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with magnesium and calcium (Invitrogen), which was adjusted to the reported pH using citric acid. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, PBS buffer was replaced with 1 ml DMEM containing FBS and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Samples were then fixed and stained using a Hema 3 stat pack staining kit (Fisher).

Protein structure accession numbers.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) (PDB codes 3QQB, 3QQE, 3QQI, and 3QQO).

RESULTS

Mutation R106H in HA2.

Residue 106 of HA2 is located at a key position where the long, central, intertwined α-helices start to diverge from each other in the prefusion structure and at a different, but also critical, location in the postfusion structure where the refashioned, long helix terminates and folds back on the remaining helical residues to form the trimer of hairpins at fusogenic pH (Fig. 1 A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This residue is differentially conserved in the two major groups of known HA subtypes that are classified by sequence similarities. In group 1, which includes the H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11, H12, H13, and H16 subtypes, it is conserved as an arginine or lysine. In group 2, a histidine is conserved in the HAs of the H3, H4, H7, H10, H14, and H15 subtypes (20). Due to its unique location, a panel of Arg106 mutants was overexpressed and investigated for their effects on HA fusion. Unexpectedly, an HA2R106H mutation was found to greatly improve the stability of H2 HA at acidic pH (Fig. 1B to D). When the pH drops below 5.5, wild-type H2 undergoes an irreversible structural transition and displays a significant shift in blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). The dose-response curve of wild-type H2 suggests a pH of 5.3 for 50% conversion to the postfusion state in 1 h when incubated at 37°C. In comparison, H2-HA2R106H largely maintains a near-native conformation at a pH as low as 4.3 (Fig. 1B and C).

The stability of HA2R106H was also measured by the susceptibility of the HA to trypsin digestion after acid treatment. H2 HA in its prefusion conformation resists trypsin digestion. At fusogenic pH, irreversible conformational changes expose sites of susceptibility for trypsin digestion. Around 50% conversion is reached at pH 5.2 and pH 4.2 for the wild type and HA2R106H, respectively, as determined by measuring the residual undigested HA (Fig. 1D; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

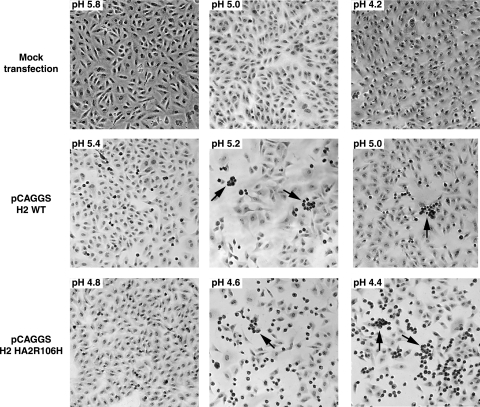

The conformational changes observed above by BN-PAGE and trypsin digestion are directly related to HA-mediated membrane fusion, as suggested by a cell-based syncytium assay (Fig. 2). Vero cells transfected with the pCAGGS H2 HA wild-type plasmid showed syncytium formation at pH 5.2. In comparison, H2-HA2R106H induces syncytium formation only at pH 4.6 and below. The conditions for membrane fusion correlate well with those for irreversible structural transitions of HA. The fusogenic ability of H2-HA2R106H suggests that the mutant undergoes conformational transitions similar to those of the wild type, but the irreversible structural rearrangements can only be initiated under much more acidic conditions.

Fig. 2.

HA-induced membrane fusion in Vero cells. Representative images of acid-treated cells show syncytium formation in HA-transfected cells. The pH value is given in the top left corner of each image. Cells transfected with the H2-HA2R106H plasmid only form syncytia under much more acidic conditions than do cells transfected with wild-type H2 HA.

At pH conditions close to the fusogenic pH, wild-type H2 adopts a conformation that cannot be discriminated by gel shift assay and protease digestion (Fig. 1B and D). Under these conditions, the protein is very labile, which prohibits direct structural investigation. The acid-stable HA2R106H mutant allows crystallization and structural determination at pH values as low as 5.1. The structure of HA2R106H at low pH would be expected to resemble the HA immediately prior to irreversible conversion and thus provides new clues about the early events concerning protein conformational changes that are required for HA fusion. The structural shift from the prefusion state to the acid-induced form of the H2-HA2R106H HA is likely the predecessor of the eventual large-scale, irreversible conformational changes in wild-type HA during membrane fusion.

Overall structures.

The H2-HA2R106H HA in its acid-induced intermediate form (the “relaxed form”) was crystallized in citrate buffer at pHs between 5.6 and 5.1. Three structures were solved at pHs 5.6, 5.3 and 5.1, at 2.87-, 2.90-, 3.10-Å resolutions, respectively. Since no significant differences were noted among the three structures, only one (at pH 5.3) is presented here for further analysis. The crystal structure of H2-HA2R106H HA at pH 8.1 (the “prefusion state”) was also determined (1.97-Å resolution) for comparison and displays few changes from that of wild-type H2 HA (50). The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the wild type and the mutant at neutral pH is 0.18 Å for all Cα atoms, indicating minimal structural perturbation by the mutation. The acid-induced form of the H2-HA2R106H HA shows considerable structural changes from its neutral form, with an RMSD for all Cα atoms of 1.77 Å. Whereas the stem region and the receptor-binding subdomain superimpose well between the two structures, larger differences occur in the region of the B loop and in the neighboring vestigial esterase and F′ fusion subdomains (see Fig. S6 to S8 in the supplemental material).

To determine whether these structural transitions are proton driven and reversible, the H2-HA2R106H HA protein was incubated in sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.0 (37°C for 1 h) and then titrated back to pH 8. The crystal structure of the reneutralized sample is nearly identical to the structure of H2-HA2R106H in the prefusion state at neutral pH, with an RMSD of only 0.15 Å for all Cα atoms (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). The only difference is the side chain orientation of His106 of HA2, which remains rotated about 180o on χ1 upon prolonged incubation at fusion pH (see Fig. S10).

B loop.

The B loop of H2-HA2R106H HA adopts noticeably different conformations when crystallized at different pH values (Fig. 3 A). In the neutral-pH structure, the B loop displays a “collapsed” conformation and closely packs against the central coiled coil, as in wild-type H2 HA (50). The interactions are mostly hydrophobic, involving two highly conserved phenylalanines (HA2 Phe63 and Phe70) on loop B. The aromatic side chains of Phe63 and Phe70 in HA2 are partially buried in two separate cavities at the subunit interface. Phe63 makes an aromatic stack with Phe88 of HA2 and is surrounded by Glu85 and Trp92 of HA2 and Lys83′ from the neighboring subunit (Fig. 3B). Phe70 is situated near the top of the central helix. The benzyl group of Phe70 is encircled by Leu77, Glu78, Asn81, and an intersubunit salt bridge of Glu74-Arg76′ (Fig. 3C). At acidic pH, the B loop moves away from the central helices and exhibits an arch-like conformation (Fig. 3A). Phe63 Cα at the top of the newly formed arch is displaced 8.7 Å from its prefusion structure. The positional shift of the B loop is also accompanied by a rotation of about 180°, clockwise when viewing toward the viral membrane. The structural transitions unwind the last helical turn of helix A in HA2 and cause substantial separation between the B loop and the central helix. A total of ∼400 Å2 of intrasubunit interface is lost within each HA2 protomer.

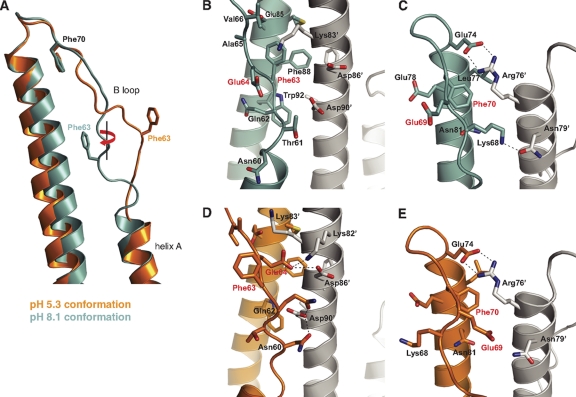

Fig. 3.

The B loop of H2-HA2R106H adopts different conformations when crystallized at pH 8.1 (prefusion state, cyan) and pH 5.3 (“relaxed” state, orange). (A) The relaxed-state conformation of H2-HA2R106H displays greater separation between the B loop and the central helix of HA2. Rotation of the B loop leads to solvent exposure of previously buried Phe63 and to a lesser extent Phe70 (see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). The transition of the B loop from its prefusion conformation (B and C) to the relaxed conformation (D and E) is likely mediated by the neutralization of the highly conserved Glu64 and Glu69 as seen in an ∼90° view from that in panel A. The neighboring HA2 subunit in the HA trimer on the right is colored in gray.

The most notable feature of the transition occurs at Phe63, whose aromatic side chain is extruded from the cavity and exposed to solvent in the relaxed conformation. Phe70 also rotates along the same direction, although to a much lesser extent, about 30° (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). Any further movement of Phe70 would require breakage of the Glu74-Arg76′ salt bridge. Thus, Phe63 and Phe70 are trapped close to the central helices in the prefusion state but are unfettered at acidic pH through structural transitions of the B loop. Release of the phenylalanines from their binding sockets appears then to destabilize the B-loop conformation and enable its participation in formation of a continuous helix (consisting of helix A and B loop) in HA2. After the loop-to-helix transition, Phe63 and Phe70 are key helix packing residues of the newly formed, triple-stranded coiled coil in the postfusion structure (6, 19). A similar mechanism employing buried phenylalanines in an interhelical loop as a “conformational lock” is also observed in the crystal structures of the pore-forming toxin cytolysin A (29), which undergoes analogous “spring-unloading” structural rearrangements to form the transmembrane pore upon membrane association.

Two highly conserved glutamate residues on the B loop, Glu64 and Glu69, are adjacent to Phe63 and Phe70, respectively (Fig. 3B and C). They adjust to adopt significantly different conformations at different pHs and likely contribute to the large-scale rotation of the B loop. Although the pKa of a free glutamate side chain is about 4.4, protonation of the carboxylate group could occur at the HA fusion pH (5, 6), depending on its chemical environment in the protein (39). In the prefusion state, the Glu64 and Glu69 carboxylates point away from the central coiled coil, where Glu64 is exposed to solvent and Glu69 forms an ionic quartet with HA1 Glu89, Lys109, and Lys269 (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). In the relaxed conformation at low pH, Glu64 and Glu69 move toward helix B of the neighboring HA2 and form polar interactions with residues from the neighboring subunit (Fig. 3D and E). Glu64 is within 3.5 Å from HA2 Lys82′ and Asp86′. Glu69 forms a new contact with HA1 His110 and is close to HA2 Asn79′. Protonation of Glu64 and Glu69 would facilitate burial of the glutamate side chains within the HA2 trimer and may be the driving force for the B-loop rotation.

HA1.

HA1 assists the structural transitions of the B loop in H2 HA. During transformation between conformational states, the receptor-binding subdomain remains structurally unchanged (Fig. 4 A and B) and moves only slightly within the HA trimer. Yet a modest structural deformation occurs within HA1. The conformational change in the membrane-distal domain and the top part of the F′ fusion subdomain can be modeled as a hinge-bending rotation of one subdomain relative to the other (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S12 in the supplemental material). The movement of the F′ fusion subdomain can be fitted by a 15o swing around a hinge point located within the vestigial esterase subdomain. This hinge motion leads to a rigid-body shift of the F′ fusion subdomain by up to 5 Å (see Fig. S12A). In the context of the HA trimer, a positional shift of the F′ fusion subdomain toward the central axis in response to acidic pH allows it to insert into the space between the arched B loop and the central helix (see Fig. S12). The backbone of the F′ fusion subdomain remains largely rigid during the shift (RMSD of 0.43 Å for all Cα atoms), whereas changes in side chain orientation optimize interactions and surface complementation with the B loop in HA2 (see Fig. S12B and C). The shift of the F′ fusion subdomain increases the contact area between HA1 and HA2 by nearly 200 Å2. Noticeably, the arch conformation of the B loop is partly stabilized by main-chain hydrogen bonds in an antiparallel, β-sheet-type interaction between Glu64-Val66 of HA2 and Thr301-Gly303 of HA1 at low pH (see Fig. S13). Lys307 in the F′ fusion subdomain inserts into a cavity under the newly formed arch and forms cation-π interactions with Trp92 from the central helix of HA2. Intrusion of the F′ fusion subdomain at low pH causes a subtle separation between the antiparallel α-helices in HA2 (Fig. 3A). The loss in the intrasubunit interface area in HA2 in this relaxed form, however, is well compensated by a corresponding increases in the size of the intrasubunit HA1-HA2 and intersubunit HA2-HA2 interfaces.

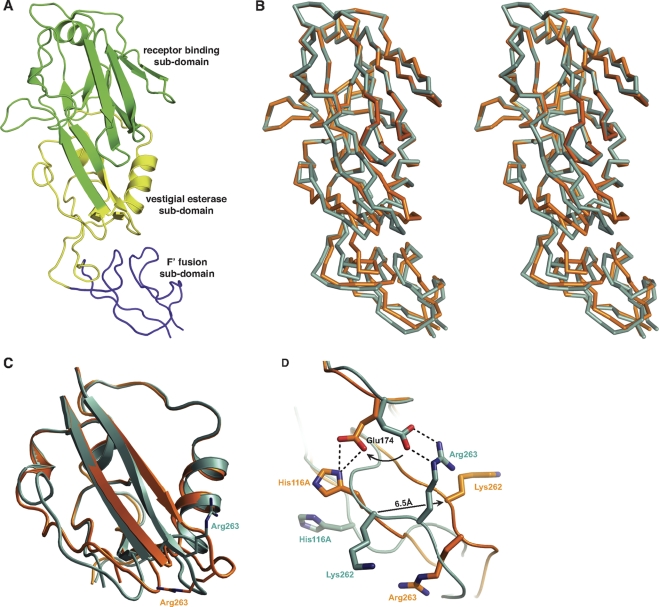

Fig. 4.

The conformational changes of the B loop are assisted by a deformation of HA1. (A) Subdomain organization of HA1. From top to bottom, it is comprised of receptor-binding, vestigial esterase, and F′ fusion subdomains. The N- and C-terminal tails of the F′ fusion subdomain are not shown in the figure. (B) The deformation of HA1 could be fitted by a hinge-like motion between subdomains. The stereo image of HA1 structures superimposed on the receptor-binding subdomain shows a significant rigid-body shift of the F′ fusion subdomain in response to low pH. (C) The hinge region is located at the vestigial esterase subdomain, which undergoes significant deformation at fusogenic pH. (D) A three-way switch formed by ionic residues (His116A, Glu174, and Arg263) in HA1 is observed at the interface between the receptor-binding and vestigial esterase subdomains. The molecular switch adopts difference conformations under different pHs, in accord with the conformational changes occurring in HA.

The vestigial esterase subdomain experiences significant deformation (RMSD of 1.77 Å for all Cα atoms) (Fig. 4C) and serves as the relative flexible linker between the rigid receptor-binding and F′ fusion subdomains. Prominent conformational differences are observed at the antiparallel β-sheet connecting with the receptor-binding subdomain (Fig. 4C). At low pH, the twisted β-sheet in the prefusion state extends and causes deformation of the vestigial esterase subdomain. The top part of the subdomain remains relatively stationary, in accord with the relatively immobile, receptor-binding subdomain attached to it. The largest shifts (5 to 6 Å) are registered in the loops at the interface with the F′ fusion subdomain. Detailed examination of the vestigial esterase subdomain reveals an intriguing ionic switch near the base of the antiparallel β-strands (Fig. 4C and D). In the prefusion state, a salt bridge is formed between Glu174 from the receptor-binding subdomain and Arg263 at the end of the β-sheet. This ionic interaction enforces a bulge between Ile260 and Arg263 and twists the β-sheet significantly. At low pH, the Glu174 side chain breaks free from the salt bridge and rotates about 90o to form hydrogen bonds with His116A. Relieved from these ionic constraints, the β-sheet straightens and Arg263 rotates away from Glu174 (Fig. 4D). The conformational changes are reversible, since pH reneutralization restores the ionic bridge and the membrane-distal domain structure (see Fig. S14 in the supplemental material).

Two major sites of ionic interactions at the HA1-HA2 interface are dissociated during the transition from the prefusion to the relaxed structure (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material) and include the charge quartet involving Glu69 on the B loop as discussed above. Mutations of the charge quartet weaken the stability of the HA prefusion trimer (34). In another patch, HA1 Lys310 from the F′ fusion subdomain forms an ionic triad with Asp86 and Asp90 of HA2 in the prefusion structure. Dissolution of the salt bridges between HA1 and HA2 is necessary to permit the conformational changes in loop B. However, the membrane-distal domain of HA1 in the prefusion state is not trapped in its metastable conformation by these salt bridges at the interface. Rather, the HA1 domain is stabilized at different conformations under different pH conditions. A construct containing only the receptor-binding and vestigial esterase subdomains of H2 HA, when crystallized at pH 8.1, adopts a conformation similar to that of the corresponding regions in the HA prefusion structure (see Fig. S15).

DISCUSSION

Stabilizing effect of HA2R106H mutation.

The HA2 HA2R106H mutation drastically improves the stability of H2 HA and inhibits its irreversible structure transition well below the fusogenic pH. The mutation is relatively conservative, from an arginine, as conserved in the H1 subtype (group 1), to a histidine, as conserved in the H3 and H7 subtypes (group 2). Understanding why HA2 His106 specifically stabilizes H2 HA could provide a clue to the molecular mechanism of HA fusion activation. Residue 106 of HA2 is located within an intersubunit cavity close to the 3-fold axis of the HA trimer (37) (Fig. 5). Ionic residues at or near this cavity are the only residues that experience different solvent environments before and after the insertion of fusion peptide into the cavity at the trimer interface, a necessary priming step of HA fusion (9). Because of the apparent relationship between the chemical environment of these residues and the HA sensitivity to low pH, they are suggested to play a critical role in fusion activation (37).

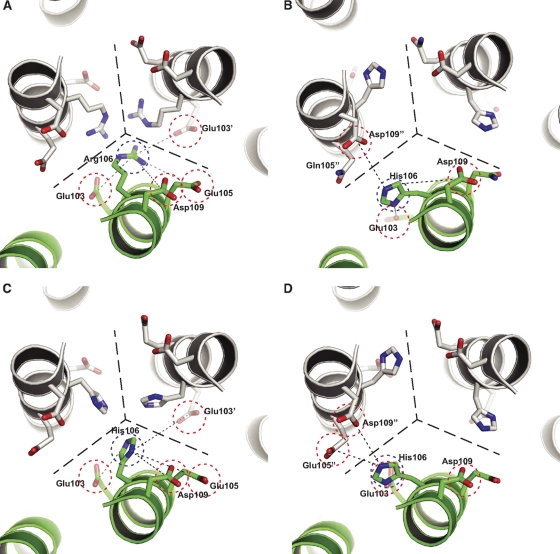

Fig. 5.

Local environment of HA2 residue 106 in various crystal structures. (A) wild-type H2 HA (PDB 3KU3) (50), representative of H1 subtype. (B) H3 HA (PDB: 2HMG) (48). (C and D) H2-HA2R106H mutant before (C) or after (D) low-pH treatment. The combination of Arg106/Glu105 is conserved in H1, whereas the H3 subtype features His106/Gln105. The “mismatch” of His106 and Glu105 appears then to stabilize H2 HA under acidic conditions.

Residues that line the cavity display clade-specific amino acid combinations and individual local conformations (37). In the H1 group, which includes H2, Arg106 points toward the 3-fold axis of the HA trimer (Fig. 5A). The crowding of the positive charges is alleviated by conserved acidic residues lining the cavity: HA2 Glu103, Glu105, and Asp109. Asp109 is located at the entrance of the cavity and forms hydrogen bonds with the fusion peptide in its prefusion state. In the H3 subtype, the imidazole side chain of His106 rotates away from the central axis and forms hydrogen bonds with HA2 Glu103 and Asp109" (Fig. 5B). A charge-neutral Gln105 replaces Glu105 of H1. The two residue differences cause little conformational perturbation to the cavity except for the side chain orientation of residue 106. Charge interactions within the cavity stabilize HA in its prefusion conformation. Replacement of Arg106 with Ala, Met, or Gln weakens trimer association in H2 HA (see Fig. S16 in the supplemental material).

In the crystal structures of the H2-HA2R106H mutant, His106 projects toward the central axis before acid treatment (Fig. 5C), similar to H1 Arg106 (Fig. 5A), but gradually flips to a rotamer conformation (Fig. 5D) similar to that of H3 (Fig. 5B) after acid treatment. Thus, the H3-like orientation is more stable under fusogenic pH. The highly similar local structures raise the intriguing question of why His106 selectively stabilizes H2 but not H3. We suggest that the HA2R106H mutation disrupts the precise balance of charged residues in HA. Ionic residues in the cavity contribute to the trimer stability of HA at neutral pH through intersubunit charge interactions and hydrogen bonds. At fusogenic pH, acidic residues in the region are partially neutralized. The resulting excess of positive charge from residue 106 destabilizes HA and leads to fusion-related conformational changes. To ensure the structural transition occurs at the pH of the late endosome during viral infection, ionic residues in the cavity are highly conserved in clade-specific groups. Arg106 is accompanied by Glu105 in group 1 subtypes, whereas the less basic His106 is matched up with Gln105 in group 2, as shown in the H1 and H3 subtypes, respectively. A mismatch of the two residues shifts the threshold of fusion activation away from the normal fusogenic pH.

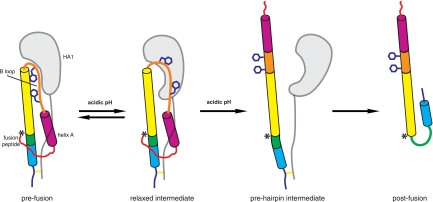

“Spring unloading” in influenza virus hemagglutinin.

Our study provides structural insights into the early events of B-loop “spring unloading” during H2 hemagglutinin fusion (Fig. 6). On lowering of the pH, the B loop moves away from the central helical bundle of HA2 and adopts a relatively loose conformation (Fig. 6, left two schematics). The open conformation of loop B is essential to its eventual loop-to-helix transition, since the refolding process would benefit from the relief of the structural constraints imposed in the prefusion state. This structural transition precedes the likely irreversible dissociation of the two antiparallel α-helices of HA2 in the prefusion state (Fig. 6, right two schematics) and represents one of the early reversible steps of HA fusion. A group of residues at or near the B loop is involved in pH sensing, as interpreted by our structural analyses and comparisons. These residues are highly conserved among different HA subtypes, with only a few exceptions. H1 HA contains Thr64 in the B loop instead of Glu64. The lack of a pH sensor at this position in H1 is compensated by the segment of the B loop near Phe63 adopting an arched conformation, much like the relaxed conformation of H2 HA, as shown in the crystal structures of H1 HAs (17, 41, 49). Some other structural variations arise during influenza virus evolution, since the B loops from different subtypes display different profiles and different side chain dispositions (20, 37). However, the high conservation of key residues on loop B suggests a common theme of the B loop being partially relieved from its metastable prefusion state in the early steps of fusion activation.

Fig. 6.

Schematic view of proposed conformational steps of influenza virus HA during fusion. The crystal structure of H2-HA2R106H provides identification of an early intermediate in the sequence of events in HA fusion. At fusogenic pH, the B loop of HA2 adopts an open-like conformation, aided by deformation of HA1. In the next step, protonation of residues on the trimer interface induces conformational changes within the central helices. This precedes the loop-to-helix transition that results in the extended prehairpin intermediate. The collapse of the extended intermediate leads to the postfusion trimer. Only one protomer out of the HA trimer is shown for clarity. The peptide segments are colored as Fig. 1A. The approximate location of HA2 residue 106 is marked “*.”

The structural deformation of the HA1 accompanies the initial release of the B loop. This observation contradicts some previous notions that the individual subunits of the membrane-distal domain are structurally rigid during HA fusion (38, 46). Previously, the membrane-distal domain of H3 was isolated from acid-induced, postfusion HA, and its crystal structure was determined (3). The prepared HA1 fragment retains its structure in the prefusion HA conformation and the capability to bind neutralizing antibody, leading to the suggestion that HA fusion involves rigid body dissociation of the HA1 globular heads away from the trimer axis (3). This apparent disagreement could be explained by a reversible distortion of the domain, as we observe for H2 HA. Presumably, such a distortion is observed only when the protein sample is captured at or close to the fusion pH. The H3 membrane-distal domain structure was crystallized at pH 6 (3), which is likely not acidic enough to induce or retain any fusion-related conformational changes. As shown in H2 HA, the deformation in the membrane-distal domain does not disrupt the major antigenic sites, and thus it is unlikely to be detectable by conventional biochemical methods, such as antibody binding and limited proteolysis. The degree of deformation also appears to be subtype specific. The presence of an ionic switch triad of Glu174-Arg263-His116A in HA1 varies greatly across all HA subtypes. Similar ionic interactions are found near the equivalent site in other HAs, but their involvement in pH sensing is not immediately apparent. The subtype-specific domain deformation is consistent with differences observed in the curvature or relative disposition of the membrane-distal domain and the conformation of the B loop in the prefusion state in the various HA subtypes (see Fig. S17 in the supplemental material).

Complete conversion of the B loop into the helical structure would require relocation of the preceding helix A of HA2. We did not observe any movement of the fusion peptide or helix A in the structures of the H2-HA2R106H mutants, even at pH 5.1. Thus, the dissociation of helix A from the HA stem region and the release of fusion peptide likely only follow the structural rearrangement of the central helices, which, in this case, is inhibited by the HA2R106H mutation. Residue 106 of HA2 is located near the boundary where the central helices splay apart and the hydrophobic coiled-coil interactions are replaced by intersubunit, charge-charge interactions. Low pH neutralizes acidic residues in the lower half of the central helices and serves to disrupt intersubunit interactions in two ways. It weakens the intersubunit ionic attractions through a loss of charge-charge pairs and strengthens repulsions through an excess of nonneutralized, positively charged residues at the interfaces. These perturbations cause structural rearrangement around the lower part of HA2 central helices, likely dissociation of subunit-subunit interfaces, and the irreversible steps of HA fusion.

The above scenario suggests a central role for these ionic residues in the vicinity of HA2 residue 106 in fusion activation. It also helps explain why uncleaved HA0 and cleaved HA respond to pH stimulus differently (9). Previous studies have suggested that the membrane-distal domain of HA1 is also critical for HA fusion. During fusion, dissociation of HA1 from the trimer spike is necessary for completion of HA2 spring unloading (2, 18, 23). Engineered intersubunit disulfide bonds, as well as antibody binding, that prohibit dissociation of the HA1 heads also inhibit HA-mediated membrane fusion (2, 18, 23). We show that a similar inhibition can be achieved by stabilizing the stem region of HA through mutations in HA2 as shown here or, as we previously showed, through antibody binding to the stem region (15). We propose that HA1 dissociation and HA2 spring unloading are concurrent, synchronized events during fusion. Disruptions of intersubunit ionic interactions at the HA1 membrane-distal domain and the HA2 central helices are necessary to jump-start the irreversible, fusion-related conformational changes. Other early steps in HA fusion previously described, including the exposure of the fusion peptide (26, 47) and partial separation of HA1 (47), could arise after formation of this early intermediate state that we report here but would precede the more extensive, irreversible conformational rearrangements that lead to the fusion-active conformation.

The structure of the H2 HA mutant at fusion pH represents one of the first atomic-resolution snapshots of putative fusion intermediates for viral envelope proteins (27, 43). Although low pH is the sole trigger for fusion in influenza virus HA, it does this in a well-regulated, stepwise manner. As indicated by our study, each step is likely initiated by protonation of a discrete set of residues. The first protonation event leads to conformational changes within HA1 and “primes” the B loop for refolding events. Later protonation steps disrupt the trimer interfaces in order to complete the loop-to-helix transition of the B loop, leading to the prehairpin stage and postfusion conformation. Thus, HA fusion requires at least two independent pH stimuli, which then acidify different residues in a particular chronological order. This sequential activation is important for orderly protein refolding and efficient fusion, given the large-scale structural transition from the prefusion state to the postfusion state.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI058113 (to I.A.W.) and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology. X-ray diffraction data sets were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, beamlines 9-2 and 11-1, and at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline 23ID-B (GM/CA-CAT).

This is publication 20685 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 2 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D. 2005. The Phenix refinement framework. CCP4 Newsl. 2005(42):contribution 8 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbey-Martin C., et al. 2002. An antibody that prevents the hemagglutinin low pH fusogenic transition. Virology 294:70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bizebard T., et al. 1995. Structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with a neutralizing antibody. Nature 376:92–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blanc E., et al. 2004. Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr. D 60:2210–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bottcher C., Ludwig K., Herrmann A., van Heel M., Stark H. 1999. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at neutral and at fusogenic pH by electron cryo-microscopy. FEBS Lett. 463:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bullough P. A., Hughson F. M., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. 1994. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature 371:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carr C. M., Chaudhry C., Kim P. S. 1997. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:14306–14313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carr C. M., Kim P. S. 1993. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell 73:823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen J., et al. 1998. Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell 95:409–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen J., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. 1999. N- and C-terminal residues combine in the fusion-pH influenza hemagglutinin HA2 subunit to form an N cap that terminates the triple-stranded coiled coil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:8967–8972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chernomordik L. V., Kozlov M. M. 2003. Protein-lipid interplay in fusion and fission of biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:175–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 50:760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daniels R. S., et al. 1985. Fusion mutants of the influenza virus hemagglutinin glycoprotein. Cell 40:431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis I. W., et al. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ekiert D. C., et al. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Emsley P., Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60:2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gamblin S. J., et al. 2004. The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science 303:1838–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Godley L., et al. 1992. Introduction of intersubunit disulfide bonds in the membrane-distal region of the influenza hemagglutinin abolishes membrane fusion activity. Cell 68:635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gruenke J. A., Armstrong R. T., Newcomb W. W., Brown J. C., White J. M. 2002. New insights into the spring-loaded conformational change of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 76:4456–4466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ha Y., Stevens D. J., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. 2002. H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus haemagglutinin structures: possible origin of influenza subtypes. EMBO J. 21:865–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrison S. C. 2008. The pH sensor for flavivirus membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 183:177–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison S. C. 2008. Viral membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:690–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kemble G. W., Bodian D. L., Rose J., Wilson I. A., White J. M. 1992. Intermonomer disulfide bonds impair the fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 66:4940–4950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klock H. E., Lesley S. A. 2009. The polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 498:91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korte T., Ludwig K., Booy F. P., Blumenthal R., Herrmann A. 1999. Conformational intermediates and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 73:4567–4574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leikina E., Ramos C., Markovic I., Zimmerberg J., Chernomordik L. V. 2002. Reversible stages of the low-pH-triggered conformational change in influenza virus hemagglutinin. EMBO J. 21:5701–5710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li L., Jose J., Xiang Y., Kuhn R. J., Rossmann M. G. 2010. Structural changes of envelope proteins during alphavirus fusion. Nature 468:705–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. 2005. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D 61:458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mueller M., Grauschopf U., Maier T., Glockshuber R., Ban N. 2009. The structure of a cytolytic alpha-helical toxin pore reveals its assembly mechanism. Nature 459:726–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53:240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puri A., Booy F. P., Doms R. W., White J. M., Blumenthal R. 1990. Conformational changes and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin of the H2 and H3 subtypes: effects of acid pretreatment. J. Virol. 64:3824–3832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qiao H., et al. 1998. Specific single or double proline substitutions in the “spring-loaded” coiled-coil region of the influenza hemagglutinin impair or abolish membrane fusion activity. J. Cell Biol. 141:1335–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rachakonda P. S., et al. 2007. The relevance of salt bridges for the stability of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. FASEB J. 21:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reed M. L., et al. 2010. The pH of activation of the hemagglutinin protein regulates H5N1 influenza virus pathogenicity and transmissibility in ducks. J. Virol. 84:1527–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosenthal P. B., et al. 1998. Structure of the haemagglutinin-esterase-fusion glycoprotein of influenza C virus. Nature 396:92–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Russell R. J., et al. 2004. H1 and H7 influenza haemagglutinin structures extend a structural classification of haemagglutinin subtypes. Virology 325:287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Srivastava J., Barber D. L., Jacobson M. P. 2007. Intracellular pH sensors: design principles and functional significance. Physiology (Bethesda) 22:30–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stevens J., et al. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stevens J., et al. 2004. Structure of the uncleaved human H1 hemagglutinin from the extinct 1918 influenza virus. Science 303:1866–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thoennes S., et al. 2008. Analysis of residues near the fusion peptide in the influenza hemagglutinin structure for roles in triggering membrane fusion. Virology 370:403–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voss J. E., et al. 2010. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature 468:709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ward C. W., Dopheide T. A. 1980. Influenza virus haemagglutinin. Structural predictions suggest that the fibrillar appearance is due to the presence of a coiled-coil. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 33:441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weissenhorn W., Hinz A., Gaudin Y. 2007. Virus membrane fusion. FEBS Lett. 581:2150–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. White J. M., Delos S. E., Brecher M., Schornberg K. 2008. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43:189–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. White J. M., Wilson I. A. 1987. Anti-peptide antibodies detect steps in a protein conformational change: low-pH activation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Cell Biol. 105:2887–2896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilson I. A., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature 289:366–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu R., et al. 2010. Structural basis of preexisting immunity to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. Science 328:357–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xu R., McBride R., Paulson J. C., Basler C. F., Wilson I. A. 2010. Structure, receptor binding, and antigenicity of influenza virus hemagglutinins from the 1957 H2N2 pandemic. J. Virol. 84:1715–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.