Abstract

Implicit with the use of animal models to test human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) vaccines is the assumption that the viral challenge of vaccinated animals reflects the anticipated virus-host interactions following exposure of vaccinated humans to HCMV. Variables of animal vaccine studies include the route of exposure to and the titer of challenge virus, as well as the genomic coding content of the challenge virus. This study was initiated to provide a better context for conducting vaccine trials with nonhuman primates by determining whether the in vivo phenotype of culture-passaged strains of rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) is comparable to that of wild-type RhCMV (RhCMV-WT), particularly in relation to the shedding of virus into bodily fluids and the potential for horizontal transmission. Results of this study demonstrate that two strains containing a full-length UL/b′ region of the RhCMV genome, which encodes proteins involved in epithelial tropism and immune evasion, were persistently shed in large amounts in bodily fluids and horizontally transmitted, whereas a strain lacking a complete UL/b′ region was not shed or transmitted to cagemates. Shedding patterns exhibited by strains encoding a complete UL/b′ region were consistent with patterns observed in naturally infected monkeys, the majority of whom persistently shed high levels of virus in saliva for extended periods of time after seroconversion. Frequent viral shedding contributed to a high rate of infection, with RhCMV-infected monkeys transmitting virus to one naïve animal every 7 weeks after introduction of RhCMV-WT into an uninfected cohort. These results demonstrate that the RhCMV model can be designed to rigorously reflect the challenges facing HCMV vaccine trials, particularly those related to horizontal transmission.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous betaherpesvirus with a worldwide seroprevalence of 50 to >90% in adults (8, 14). HCMV elicits a subclinical outcome for the majority of infections in immunocompetent individuals but is a significant pathogen in those without a fully functional immune system. Groups at increased risk for HCMV clinical sequelae include immunologically immature fetuses, immunosuppressed transplant recipients, and immunodeficient AIDS patients. The nearly 4-decade quest for a vaccine that confers protective immunity against HCMV infection has focused primarily on inhibiting primary infection in women without preconceptional immunity to HCMV to prevent transplacental transmission of the virus to the fetus (30). Progress on this front has been reported for a subunit vaccine directed at viral glycoprotein B (gB), which is essential for virus attachment to fibroblasts and is a prominent target of neutralizing antibodies during natural infection (38). A clinical trial with seronegative pregnant women demonstrated that vaccination against gB can reduce primary infection in the vaccine recipients by 50% compared to levels of infection in unvaccinated controls (49). The absence of complete protection in the vaccinees suggests that the level of protective efficacy could be augmented by including additional viral antigens in the vaccine and by broadening the target population for vaccination. Since the rate of congenital HCMV infection is only 0.6 to 0.7% (22), the route for the spread of virus from infected to naïve individuals is overwhelmingly horizontal transmission of virions in bodily fluids across mucosal surfaces. Vaccine-mediated disruption of HCMV shedding should, therefore, significantly reduce the frequency of congenital infection by reducing the rate of horizontal transmission of HCMV to seronegative women.

The initial infection of mucosal epithelial cells and subsequent shedding of HCMV in mucosal fluids are essential steps in the viral life cycle within an infected host, leading to the successful spread of virus to naïve individuals within the population. The initial and final steps in this infectious cycle are relatively unexplored, since there are no well-described in vitro models for investigating bidirectional HCMV trafficking across a mucosal surface. As a first step in addressing this limitation in our understanding of HCMV's natural history, infection of rhesus macaques (RM) with rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) was used to address (i) how viral coding content affects parameters of RhCMV infection, particularly those related to the shedding of virus in bodily fluids, and (ii) the role of viral shedding in mediating the spread of RhCMV in a mixed population of infected and uninfected monkeys. The precedent for this study of nonhuman primates was an experimental inoculation of seronegative human volunteers with different HCMV strains that were distinguished by differences in the UL/b′ region of the HCMV genome (discussed below).

UL/b′ encodes multiple proteins, including those implicated in epithelial and endothelial cell tropism (UL128, UL130, UL131) (68), virion structure (UL132) (69), viral latency (UL138) (28), and modulation of host cell activation (UL141, UL142) (57, 72, 76), signaling (UL144) (17), and trafficking (UL146) (51). Supporting data have been derived largely from tissue culture studies, although there have been limited in vivo studies characterizing the patterns of infection with HCMV strains with different coding capacities. Whereas primary HCMV infection in teenagers naturally exposed to wild-type HCMV (HCMV-WT) is characterized by viremia and prolonged shedding of virus in bodily fluids (10, 81), experimental inoculation of seronegative volunteers with either the attenuated Towne or AD169 vaccine strain results in a subclinical infection without the recovery of virus (23, 41, 55, 58). The Towne strain has a complicated derivation after extensive passage on human fibroblasts and is comprised of two variant populations (13, 53, 54). UL/b′ has been deleted in one variant (varS), while the other variant (varL) retains UL/b′ but has a frameshift mutation in UL130, as well as frameshift and coding mutations in other open reading frames (ORF) throughout the genome. AD169 was passaged 54 times in cultured human fibroblasts; however, its genetic content at the time of the study was unknown (23). It is now recognized that the AD169 strain has undergone an extensive rearrangement of UL/b′, resulting in the introduction of a frameshift mutation within UL131 (21). Inoculation with another HCMV strain, Toledo, results in outcomes that are phenotypically more like those of the wild type than those of the Towne and AD169 strains (55). Experimental inoculation with Toledo led to recovery of virus from all volunteers, in addition to brief clinical signs of an infection similar to mononucleosis. A comparison of levels of HCMV shedding between wild-type- and Toledo-infected individuals suggests that the duration of shedding of Toledo is less than in those infected with HCMV-WT, with the caveat that Toledo was inoculated via a parenteral route, unlike with wild-type-infected individuals, who were mucosally exposed to the virus (10, 55, 81). The composition of UL/b′ in the particular passage of Toledo (P3) that was used in these studies is unknown. When Toledo was sequenced after 8 passages in cultured human fibroblasts, the genome contained an inversion of UL/b′ and a prematurely truncated UL128 gene (6). It is unknown during which passage(s) in culture these mutations occurred. In sum, the results from experimental inoculations of humans with different strains of HCMV support the hypothesis that ORF within UL/b′ are instrumental in the magnitude and duration of shedding of HCMV. This hypothesis was tested by taking advantage of the natural history of RhCMV in rhesus macaques.

RhCMV is endemic in both wild populations and outdoor-housed breeding corrals of rhesus macaques (9, 11, 12, 40, 74). One longitudinal survey of infants born into a corral housing 142 seropositive animals showed that RhCMV exhibits an extremely high force of infection (i.e., the annual number of RhCMV infections per 100 seronegative animals [18, 24]), such that nearly 100% of the infants (24 of 25 infants) were infected with RhCMV by 12 months of age when they remained cohoused with RhCMV-infected monkeys. The median length of susceptibility (i.e., the length of time until seroconversion) was 192 days (74). Transmission kinetics are dependent on many variables, including the number of contacts between infected and uninfected hosts, the frequency at which infected animals shed infectious virus, and the titers of virus in bodily fluids. This study shows that the genetic basis for the high force of RhCMV infection in macaques is associated with viral genes within the UL/b′ region of the RhCMV genome, including those genes encoding proteins involved in epithelial/endothelial cell tropism (RhUL128, RhUL130, and RhUL131) and alpha-chemokine-like proteins (48). Only those RhCMV strains with a full complement of UL/b′ genes exhibited patterns of shedding and horizontal transfer of RhCMV comparable to those of wild-type RhCMV (RhCMV-WT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Genetically outbred rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC), repeatedly confirmed to be RhCMV seronegative, were used for these studies. Their ages ranged from ∼1 to 3 years at the time of RhCMV inoculation. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), which is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, approved all animal protocols in advance of any procedures.

Viruses.

RhCMV strains UCD52 and UCD59 were originally isolated from the urine of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected monkeys (7, 71). Frozen virus stocks were prepared after a limited number of serial passages (≤5) on primary human fibroblasts and stored at −80°C in the early 1990s. For this study, aliquots of the original stocks of UCD52 and UCD59 were propagated for 2 and 3 additional serial passages, respectively, on primary rhesus dermal fibroblasts, and fresh virus stocks were prepared for inoculation studies. Both strains contain a full-length UL/b′ region of the genome (GenBank accession numbers GU552456 and EU130540, respectively; originally annotated as 21252 and 22659), including genes encoding three proteins involved in endothelial/epithelial cell tropism (RhUL128, RhUL130, and RhUL131) and six alpha-chemokine-like proteins (43, 48). RhCMV 68-1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (VR-677); it had been passaged on diploid human fibroblasts 7 times. A stock of 68-1 for inoculation was prepared after 3 passages in primary rhesus dermal fibroblasts. Based on a previous report that the RhCMV RhUL36 ORF can accumulate mutations during passage in fibroblasts (46), the RhUL36 ORF of the ATCC-derived 68-1 strain was confirmed by sequencing to be identical to that previously reported for 68-1 (GenBank accession number YP_068154 [not shown]). In addition, in vitro expression of the RL13 ORF of HCMV strongly inhibits viral replication, and presumably as a result, the HCMV RL13 ORF rapidly mutates in culture to a noninhibitory phenotype (20, 70). The rh05 ORF of RhCMV, a putative sequence homolog of HCMV RL13, was amplified from both UCD52 and UCD59 and sequenced (accession numbers JF433373 and JF433372, respectively). The predicted rh05 ORF of both strains were each 99% identical to the predicted translation product of the rh05 ORF of 68-1 (accession number YP_068099 [not shown]). For each of the three RhCMV strains, supernatant and cells were collected when infected cells exhibited 100% cytopathic effect and were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles of −80°C/+37°C. After sonication and low-speed centrifugation to remove cell debris, 8 ml of resuspended virions was pelleted through 3 ml of 30% sorbitol (model SW 41 rotor, 1 h at 18,000 rpm) and resuspended, and the titer of virions on telomerase-immortalized rhesus fibroblasts was determined (16), followed by storage in liquid nitrogen.

RhCMV inoculation.

Animals were inoculated with a subcutaneous delivery of RhCMV according to our published protocols (1, 15, 77). In the first study, two monkeys were experimentally coinoculated with three strains of RhCMV: UCD52, UCD59, and 68-1 (Fig. 1). Each strain was diluted in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to a concentration of 2 × 105 PFU/ml, and 0.5-ml samples of the three virus strains were individually delivered into three separate sites on the back of each animal. In the second experiment, nine RhCMV-seronegative monkeys were inoculated with just a single strain of RhCMV (3 animals each for RhCMV UCD52, UCD59, and 68-1), and three animals were mock infected with PBS. Each virus stock was diluted to 2.5 × 105 PFU/ml, and a total volume of 0.4 ml was delivered into four subcutaneous sites on the back of each animal (1 × 105 PFU/animal). The animals were housed in pairs at least 2 weeks prior to RhCMV inoculation, and each animal remained paired with the same animal for 20 weeks postinoculation (p.i.), as follows (explained in detail in Results [see Table 3]). Of the three animals per group that were inoculated with either RhCMV UCD52, UCD59, or 68-1, one animal per group was housed with one mock-infected animal. The other two animals inoculated with UCD52 were each cohoused with an animal inoculated with UCD59. Finally, the other two animals inoculated with 68-1 were housed together.

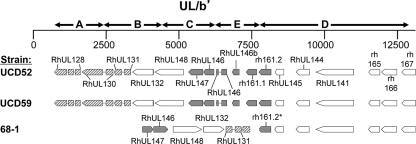

Fig. 1.

Genetic organization of the UL/b′ region of three strains of RhCMV. ORF homologous to HCMV ORF are designated by “RhUL” (48, 61). ORF without homologues in HCMV are designated with the naming scheme of Hansen et al. (indicated by “rh”) (34). Hatched boxes, three genes coding for proteins involved in epithelial tropism (RhUL128, RhUL130, and RhUL131). An inversion (segments B and C) and deletion (segment A) in the UL/b′ region of 68-1 resulted in the loss of UL128 and one exon of RhUL130, leaving only the RhUL131 ORF intact. Shaded boxes, six alpha-chemokine-like ORF. A deletion of segment E in 68-1 resulted in the loss of three of these ORF (RhUL146a, RhUL146b, and rh161.1) and a premature truncation of a fourth (rh161.2, indicated by the asterisk).

Table 3.

Housing arrangement and detection of horizontal transmission by 20 weeks postinfectiona

| Cagemate A's RhCMV strain | Cagemate B's RhCMV strain | Transmission from cagemate A to cagemate B | Transmission from cagemate B to cagemate A |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68-1 | None (mock infected) | − | NA |

| UCD52 | None (mock infected) | + | NA |

| UCD59 | None (mock infected) | − | NA |

| UCD52 | UCD59 | + | + |

| UCD52 | UCD59 | + | + |

| 68-1 | 68-1 | NA | NA |

Cagemates A and B were cohoused and inoculated with the individual RhCMV strains indicated. +, differential PCR detection in saliva and/or urine of the RhCMV strain inoculated into the corresponding cagemate; −, no detectable shedding of the RhCMV strain from the corresponding cagemate; NA, not applicable.

Sample collection and processing.

Longitudinal blood draws, oral swabs, and urine samples were collected to monitor viral and immune parameters of RhCMV challenge. Blood was processed for plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Oral swabs were collected by running a sterile Weck-Cel surgical spear (Medtronic, Jacksonville, FL) inside the lower lip, into the buccal pouch, and along the gumlines. Each swab was placed in a tube containing 1 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 200 units penicillin ml−1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 200 μg streptomycin ml−1 (Sigma), and 2.5 μg amphotericin B ml−1 (Fungizone; Invitrogen). The swabs were vigorously vortexed, and the supernatant was aliquoted (350 μl) and frozen at −80°C until DNA extraction was performed. Urine samples were obtained by temporarily placing a divider between the cohoused animals overnight at weekly or biweekly time points and separately collecting urine into pans under each animal. The urine was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,500 rpm (IEC Centra GPR8 centrifuge; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) to remove any debris and particulates. The clarified urine was then filtered through a Millex-HV 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) syringe filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Filtered urine samples were aliquoted; two were frozen at −80°C for DNA extraction, and a third aliquot was centrifuged for 1 h at 4°C and 16,000 × g to pellet virus. The urine was removed from the pellet, and 200 μl of PBS was added to resuspend the pellet. This sample was then frozen for DNA extraction. DNA was purified from plasma, saliva, and urine using a QIAsymphony DNA extraction system (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Tissue samples were collected at necropsy, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C. Tissues were treated with ATL lysis buffer (Qiagen) and proteinase K overnight at +56°C with periodic vortexing to dissociate the tissue until a single-cell preparation was achieved. Samples were purified using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) according the manufacturer's protocols.

Real-time PCR.

RhCMV DNA copies in plasma, saliva, and urine samples were detected using a previously described real-time PCR assay for RhCMV 68-1 (67). Primers and probe sequences were designed for the RhCMV gB gene. The probe was labeled with TET at the 5′ end as the reporter dye and 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) at the 3′ end as the quencher dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. Each PCR mixture contained 12.5 μl of TaqMan universal PCR master mix, 2.5 pmol of the probe, 5 μl of purified DNA (isolated from plasma, saliva, or urine), and 17.5 pmol of each primer for a total volume of 25 μl. For DNA isolated from tissues, 100 ng (in 5 μl) was used as the template. A standard curve was generated by 10-fold serial dilutions of a gB plasmid containing 100 to 106 copies per 5 μl. All samples were run in triplicate, and results were reported as average RhCMV genome copy numbers per ml (plasma, saliva, urine) or average RhCMV genome copy numbers per 105 cells. The limit of RhCMV DNA detection was 200 RhCMV genome copies per ml of plasma, saliva, or urine.

Differential PCR.

A PCR assay to differentially amplify either RhCMV UCD52, UCD59, or 68-1 was developed using primers specific to sequences within UL/b′. The sequences of the primer pairs (5′ to 3′) to amplify the different viral strains and the predicted amplicon sizes (in base pairs) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers and predicted amplicon sizes

| Amplified strain(s) | Primer | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) (location) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68-1 | Pr 68-1.1 | TGCTACGGTGACGACAACCGTCGCCACCTCGAATACC | 1,755 (RhUL132–rh161.2) |

| Pr 68-1.2 | GCACCATTCCAAATGGTAACGG | ||

| UCD52 | Pr UCD52.1 | TTTACCGCCACTGGCTTCGCCGGAACTG | 1,212 (RhUL130–RhUL131) |

| Pr UCD52.2 | ACGCAACTTAGAAACCGGTT | ||

| UCD59 + 68-1 | Pr UCD59.1 | GCACCACTCCGAAATCAATTG | 517 (RhUL130–RhUL131) |

| Pr UCD59.2 | TAGAAGTATCACCGAAGCCATAACGC |

The amplification of target sequences from both the 68-1 and UCD59 genomes with the UCD59.1/.2 primer pair could be further differentiated by a failure of the 68-1.1/.2 primer pair to amplify a target sequence from UCD59.

ELISA.

Antibodies binding to total RhCMV antigens were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using extracts of RhCMV-infected rhesus dermal fibroblasts by following previously published protocols (78, 80). Briefly, 96-well microplates (Immulon 4 HBX; Dynex Technologies, Inc.) were coated overnight at +4°C with RhCMV antigens (0.25 μg/well) in 100 μl of coating buffer: Hanks buffered salt solution (HBSS)–0.375% bicarbonate buffer (GIBCO). The plates were washed six times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T; wash buffer) and blocked with 300 μl/well of PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 h at room temperature. After being washed six times, plasma/serum samples, diluted 1:100 in 1% BSA–PBS-T (dilution buffer), were added to duplicate wells (100 μl/well) and incubated for 2 h at +25°C. The plates were washed six times with PBS-T, and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-monkey IgG (KPL, Inc.), diluted to empirically determined optimal concentrations in 1% BSA–PBS-T, was added for 1 h. The plates were subsequently washed again with PBS-T and then incubated at +25°C with 100 μl/well of tetramethylbenzidine liquid substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min for color development. The reaction was terminated by addition of 0.5 M H2SO4 (50 μl/well), and the absorbance was recorded spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm. Samples were considered positive when the absorbance for specific antigen was 0.1 unit or greater after the background value (no serum added) and the value for a seronegative plasma pool (20 animals previously determined to be RhCMV seronegative by Western blotting) were subtracted.

RESULTS

Coinoculation of RhCMV-naïve monkeys with three RhCMV strains.

As a first step toward testing the hypothesis that UL/b′ ORF influence the frequency and magnitude of viral shedding in body fluids, we performed an initial study in which two RhCMV-seronegative macaques (RM1 and RM2) were coinoculated with RhCMV 68-1 and two low-passage-number strains of RhCMV, UCD59 and UCD52. Both UCD59 and UCD52 were initially isolated from the urine of two macaques coinfected with SIV and RhCMV (7, 71). Despite limited passage on fibroblasts (≤5 serial passages), both strains retained tropism for rhesus epithelial cells (primary monkey kidney epithelia and rhesus retinal pigmented epithelia [unpublished observations]) and an intact UL/b′ coding content (48). The coding capacities of the UL/b′ regions of UCD59 and UCD52 are the same, but they are distinguished from each other by multiple DNA sequence polymorphisms. The coding capacities of these strains are compared to that of 68-1 in Fig. 1. RhCMV strains UCD52 and UCD59 contain a full-length UL/b′ region of the genome, including genes encoding three proteins involved in endothelial/epithelial cell tropism (RhUL128, RhUL130, and RhUL131) and six alpha-chemokine-like proteins (43, 48). RhCMV 68-1, however, has undergone a rearrangement in the UL/b′ region during passage in culture, in which the genes for RhUL128 and RhUL130 have been deleted, together with three genes encoding alpha-chemokine-like proteins.

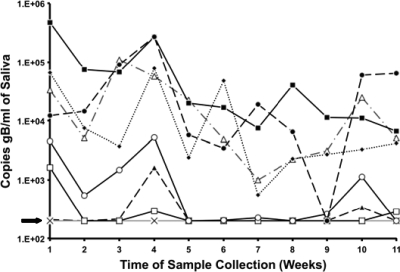

Each animal was inoculated subcutaneously with 105 PFU of each strain delivered into separate sites. Blood, saliva, and urine were collected weekly for 10 weeks p.i. and processed for DNA and real-time PCR quantification of RhCMV genomic copy numbers. Both animals were DNAemic (i.e., their plasmas were positive for RhCMV DNA) at 1 week p.i. Additionally, RM1 and RM2 were DNAemic at 6 weeks and 5 weeks p.i., respectively (limit of detection = 200 copies/ml) (Fig. 2 A). In RM1, viral shedding was first detected at 4 weeks in urine and at 5 weeks in saliva, and RhCMV DNA was detected in either fluid or both fluids at every time point through 10 weeks p.i. (Fig. 2B and C). RM2 became RhCMV DNA positive in urine at 3 weeks and in saliva at 6 weeks; viral DNA was detected in at least one sample at every time point except week 5 p.i.

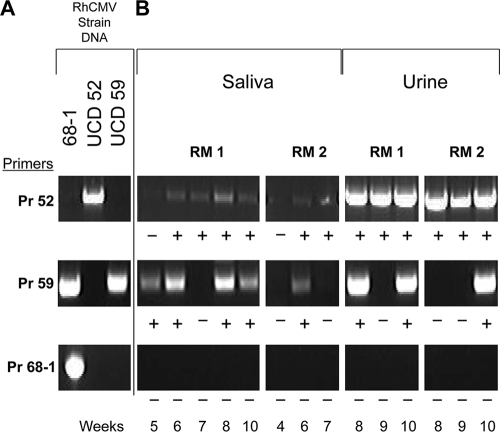

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal analysis of RhCMV coinfection in two rhesus macaques (RM). Real-time PCR detection of gB copies in plasma (A), saliva (B), and urine (C). This assay did not discriminate between individual RhCMV strains. The arrow represents the limit of detection (200 copies of RhCMV/ml).

The real-time PCR assay was based on amplification of RhCMV glycoprotein B, which did not distinguish between 68-1, UCD59 (GenBank accession number U59238), and UCD52 (accession number GU552457). To discriminate between RhCMV strains, a strain-specific PCR assay was developed using primer pairs for genetically divergent regions of UL/b′. Based on the patterns of amplification with the different primer pairs, it was possible to determine which of the three strains were present in the urine and saliva samples (Fig. 3 A). In RM1, both of the full-length UL/b′ strains RhCMV UCD59 and RhCMV UCD52 were amplified at multiple time points in saliva and urine (Fig. 3B). In RM2, RhCMV UCD59 was amplified at one time point in saliva and at another time point in urine, and RhCMV UCD52 was amplified at multiple time points in both saliva and urine. RhCMV 68-1, containing a mutated UL/b′ region, was not detected in any of the saliva or urine samples from either animal.

Fig. 3.

Differential PCR detection of RhCMV strains UCD52, UCD59, and 68-1. (A) Demonstration of the specificity of amplification of RhCMV strains with corresponding primer pairs (see Materials and Methods for details). The presence of UCD59 was determined by detection of an amplicon with Pr 59 and the absence of an amplicon with Pr 68-1. (B) Strain-specific detection of RhCMV DNA by differential PCR of saliva and urine samples from coinfected RM at different time points (in weeks). +, detection of appropriately sized amplicons; −, absence of detectable amplicon.

At 10 weeks p.i., both animals were necropsied, and viral copy numbers from multiple tissues were quantified by real-time PCR and assayed for differential detection of the RhCMV strains. In RM1, the highest copy numbers were detected in the parotid salivary gland and spleen, whereas in RM2, the highest copy numbers were found in the parotid salivary gland, pancreas, and kidney (data not shown). RhCMV UCD59 was detected in multiple tissues, including the submandibular salivary gland and kidney in both animals (Table 2). RhCMV UCD52 was also found in multiple tissues, including the parotid salivary gland, lung, and kidney in both animals. Other tissues where either RhCMV UCD52 or RhCMV UCD59 was detected included the sublingual salivary gland, bladder, pancreas, inguinal lymph node, and spleen. RhCMV 68-1 was detected in both animals only in the inguinal lymph node, which was the draining lymph node closest to the site of inoculation.

Table 2.

Strain-specific detection of RhCMV DNA by differential PCR of tissue samples from coinfected animals at 10 weeks p.i.

| Tissuea | Detection in indicated macaque of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCD52 |

UCD59 |

68-1 |

||||

| RM1 | RM2 | RM1 | RM2 | RM1 | RM2 | |

| Inguinal LN | + | + | + | + | ||

| Kidney | + | + | + | + | ||

| Pancreas | + | + | ||||

| Lung | + | + | + | |||

| Parotid SG | + | + | + | |||

| Submandibular SG | + | + | + | |||

| Sublingual SG | + | + | ||||

| Tonsil | + | |||||

| Tongue | + | |||||

| Spleen | + | + | ||||

| Bladder | + | |||||

LN, lymph node; SG, salivary gland.

Inoculation of RhCMV-naïve monkeys with a single RhCMV strain.

The observed differences in viral dissemination and shedding suggested that the genetic differences between the two full-length UL/b′ strains (UCD59 and UCD52) and 68-1 influenced the course of RhCMV infection in the context of a mixed coinoculation, particularly in relation to dissemination within the animal and shedding in bodily fluids. To address this in greater detail, we performed a second study in which 12 seronegative macaques were either inoculated subcutaneously with only one of the three RhCMV strains (3 macaques for each strain) or were mock infected with PBS (3 total). The animals were cohoused in pairs in order to evaluate the potential of horizontal transmission by each strain (Table 3). One animal inoculated with each strain was cohoused with a mock-infected animal, and two animals inoculated with UCD59 were each separately paired with an animal inoculated with UCD52. Finally, two animals inoculated with 68-1 were cohoused. Samples of blood, saliva, and urine were collected weekly through 8 weeks p.i. and then biweekly through 20 weeks p.i. and subsequently processed for quantification of viral loads by real-time PCR.

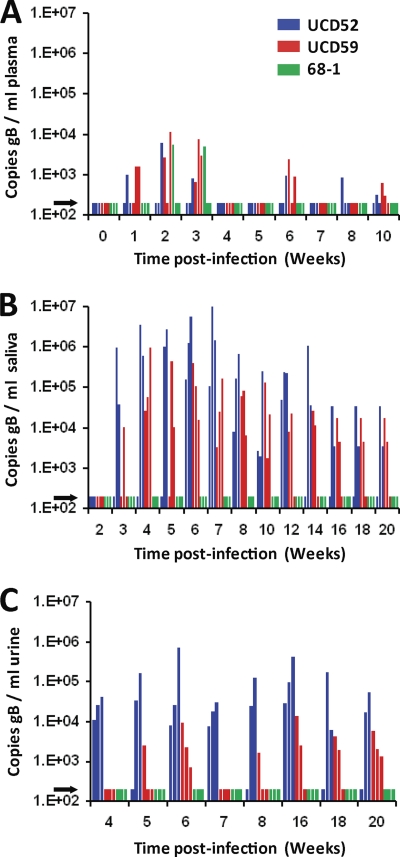

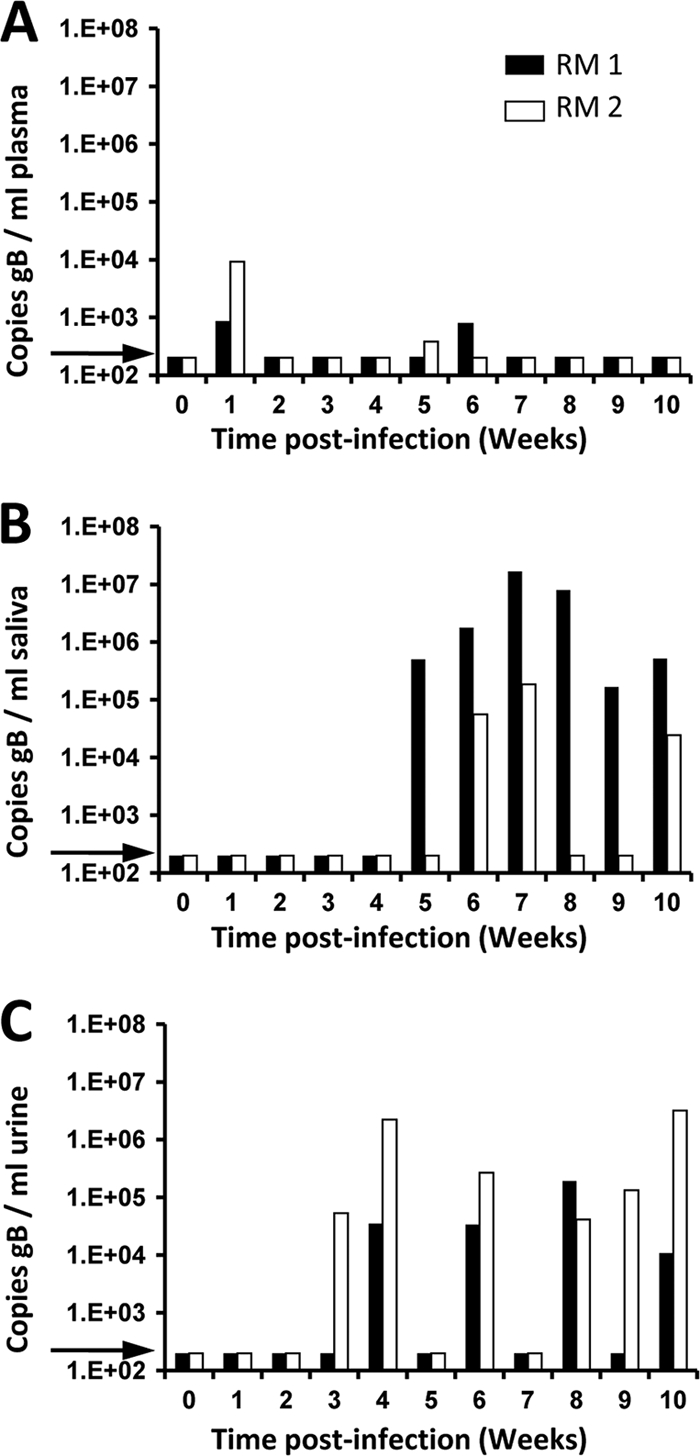

All animals, except one, who were inoculated with UCD59 or UCD52 became DNAemic between 1 and 2 weeks p.i., and they remained DNAemic for 1 to 3 weeks, followed by a second brief DNAemic phase in five of the six animals between weeks 6 and 10 p.i. (Fig. 4 A). DNAemia was not detected in one animal inoculated with UCD52 until 8 weeks p.i. Only one of the three animals inoculated with RhCMV 68-1 was detectably DNAemic (2 and 3 weeks p.i.), whereas DNAemia was not detected at any time point in the other two animals. All 9 animals inoculated with RhCMV UCD52, UCD59, or 68-1 seroconverted to RhCMV IgG antibodies between 14 and 18 days p.i. (data not shown). Viral shedding in saliva was detected in all animals inoculated with RhCMV UCD52 or UCD59 beginning between 3 and 6 weeks p.i., and RhCMV DNA remained detectable for the majority of time points through 20 weeks p.i. The RhCMV viral loads for UCD59 were mostly between 2 × 103 and 4 × 105 copies/ml, while those for UCD52 exhibited a broader range (2 × 103 to 6 × 106 copies/ml) (Fig. 4B). For both strains, the highest viral loads in saliva occurred between 5 and 8 weeks p.i. In sharp contrast, RhCMV DNA was not detected at any time point for any of the three animals inoculated with RhCMV 68-1. As with oral shedding, relatively high levels of virus were detected in urine samples from animals infected with RhCMV UCD52 and UCD59, whereas there was no evidence of viruria at any time point for animals infected with RhCMV 68-1 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Longitudinal analysis of RhCMV single-strain infection. Real-time PCR detection of gB copies in plasma (A), saliva (B), and urine (C). For plasma, only weeks 0 to 10 are presented since no RhCMV DNA was detected in plasma after 10 weeks. Urine samples were not available for weeks 2, 3, 10, 12, and 14. The arrows represent the limit of detection (200 copies of RhCMV/ml).

Horizontal transmission of UCD59 and UCD52.

Detection of RhCMV DNA in the saliva and urine of animals inoculated with UCD59 and UCD52 suggested the potential for horizontal transmission to their cagemates, which can occur when a colony-reared animal (i.e., naturally exposed to wild-type RhCMV) is cohoused with an non-RhCMV-infected animal (11). Serology or strain-specific PCR primers were used to detect the presence of horizontally transmitted virus in the uninoculated cagemates or those cagemates inoculated with a different RhCMV strain, respectively. Evidence for transmission of the RhCMV strains containing the full-length UL/b′ region was found in five animals, whereas there was no detectable transmission of RhCMV 68-1 (Table 3). Of the three mock-infected animals, only the animal cohoused with the UCD52-inoculated animal developed RhCMV-specific IgG (at 8 weeks p.i. [data not shown]). Viral shedding in urine was also detected from this animal by real-time PCR at 8 and 20 weeks p.i., and differential PCR confirmed that the strain shed in urine was RhCMV UCD52. The mock-infected animals cohoused with either UCD59- or 68-1-infected animals remained seronegative during the 20 weeks of observation. In addition to an example of RhCMV UCD52 transmission to a mock-infected cagemate, there were four examples of RhCMV transmission between cagemates that were each experimentally inoculated with different strains. The two animals inoculated with RhCMV UCD52 transmitted this strain to their RhCMV UCD59-inoculated cagemates, as demonstrated by the amplification of UCD52-specific DNA at 10 weeks p.i. in one monkey and at 14, 16, and 20 weeks p.i. in the other monkey. Likewise, the two animals inoculated with RhCMV UCD59 reciprocally transmitted this strain to their RhCMV UCD52-inoculated cagemates, as demonstrated by the PCR detection of UCD59 DNA at 10 weeks p.i. in one monkey and at 14 weeks p.i. in the other monkey. Since two of the RhCMV 68-1-inoculated animals were cohoused, transmission between these two cagemates would not have been detected by differential PCR. However, neither animal exhibited detectable shedding in either saliva or urine samples at any time point during the study.

Natural history of RhCMV shedding and transmission.

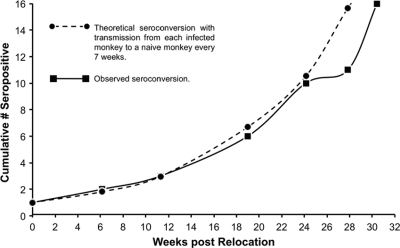

To place the shedding data from animals inoculated with UCD52 and UCD59 into a virologically relevant context, the parameters of horizontal transmission and shedding of RhCMV were analyzed in a population of animals in which wild-type RhCMV was circulating. A single RhCMV-seropositive monkey (6 years of age) was cohoused with a cohort of seronegative and sexually immature juveniles (n = 15; 1 to 2 years), and blood samples were prospectively collected for detection of RhCMV IgG. One juvenile seroconverted 43 days after being cohoused with the adult (the first time point of sampling), and all animals were RhCMV seropositive by 260 days. The median period of susceptibility was 169 days, comparable to the rate of infection in the previous survey of corral-housed animals (192 days) (74). The rate of seroconversion was almost identical to a theoretical doubling of the number of infected animals every 49 to 56 days (Fig. 5). These studies demonstrated that RhCMV transmission was exceedingly efficient in social settings where macaques had frequent contacts with one another and, potentially, multiple exposures to virus shed in saliva and/or urine.

Fig. 5.

Horizontal transmission of RhCMV to seronegative macaques. A total of 15 macaques that were RhCMV seronegative were relocated to housing together with a single RhCMV-infected monkey. The observed cumulative numbers of cohoused macaques that contained detectable IgG antibodies to RhCMV antigens are presented relative to the time (in weeks) following relocation. A theoretical seroconversion rate in which an RhCMV-infected monkey transmits RhCMV to another monkey every 7 weeks is shown for comparison.

To define the long-term pattern and magnitude of RhCMV shedding in immunocompetent monkeys, saliva samples were collected weekly for 11 weeks beginning after these animals had been cohoused for 11 months, which corresponded to 11 to 42 weeks after seroconversion. Seven of 14 monkeys that were sampled were positive for RhCMV DNA for 8 of the 11 time points, with titers up to 5 × 105 RhCMV genomes/ml of saliva (Fig. 6; data from a total of 8 animals are presented) (the limit of detection was 200 copies/ml). Two animals were intermittently positive for RhCMV DNA (3 to 4 time points), and 5 of the 14 did not exhibit detectable RhCMV DNA in saliva during the period of observation. The frequency of positive samples during each time of sampling ranged from 45 to 82% (median = 64%). There was no apparent relation between the time since seroconversion and either the magnitude or the duration of shedding. RhCMV shedding in urine was not evaluated in these animals.

Fig. 6.

Longitudinal detection of RhCMV in the saliva of naturally infected juvenile rhesus macaques at the CNPRC over 11 consecutive weeks. The dashed line and arrow represent the limit of detection (200 copies of gB/ml).

DISCUSSION

This study provides in vivo evidence that the coding content of RhCMV strains profoundly influences critical parameters of infection related to horizontal transmission of virus. Two low-passage-number RhCMV strains (UCD52 and UCD59), each of which encodes an intact UL/b′ region, exhibit a phenotype of sustained shedding of high levels of virus in body fluids that is indistinguishable from the pattern of shedding in animals naturally infected with wild-type RhCMV. RhCMV 68-1 remained below the level of detection in saliva and urine for 20 weeks after subcutaneous inoculation, in stark contrast to the shedding patterns observed with both UCD52 and UCD59. Compared to the genomes of the low-passage-number strains UCD52 and UCD59 and of naturally circulating RhCMV (48), the RhCMV 68-1 genome has lost considerable coding capacity within UL/b′, including the deletion of two ORF implicated in epithelial/endothelial cell tropism and three ORF with sequence homology to alpha-chemokines (34, 48, 61). Although mutations elsewhere in the genome cannot be ruled out, the consistency of the results between UCD52 and UCD59 together with the absence of detectable 68-1 in urine and saliva implicates UL/b′-encoded proteins as critical determinants for the prolific excretion of virus and for enabling the high rate of transmission exhibited by wild-type RhCMV in immunocompetent macaques.

It should be noted that there is a difference between our results and those of others in the detection of RhCMV 68-1 after inoculation of rhesus macaques. Our previous studies have noted infrequent and low levels of shedding of 68-1 following either intravenous or subcutaneous inoculation, far below the levels seen in naturally infected monkeys (1, 37, 78, 79). Others have noted relatively high titers of 68-1 in saliva following inoculation of either RhCMV-seronegative or -seropositive macaques, as well as the recovery of virus in urine (33, 35, 56). The reasons for differences in the quantifications of RhCMV 68-1 genomes in mucosal fluids between different groups is not known and may be related to differences in methodologies. However, whatever the absolute number of genomes per unit volume of mucosal fluid, the salient point remains that our results unequivocally demonstrate that 68-1 is impaired for excretion in a side-by-side comparison with UCD52 and UCD59, the latter of which strongly recapitulates the magnitude of shedding observed in naturally infected animals.

Since the vast number of HCMV infections are acquired horizontally by mucosal exposure to virus shed in body fluids, inhibition of shedding constitutes a rational point of interruption in the viral life cycle to protect those most at risk for clinical sequelae from primary infection, particularly fetuses in women with a primary HCMV infection. Vaccination of seronegative individuals, particularly young children, who would otherwise pose the greatest threat for horizontally transmitting virus to pregnant women, may provide a strategy complementary to vaccinating seronegative women to minimize the potential for primary infection during pregnancy (3–5, 29, 44). Based on our results, the UL/b′ ORF that are deleted in 68-1 represent potential targets for vaccine-mediated intervention to significantly minimize the potential for the spread of virus to naïve hosts. Translating these findings into vaccine studies of nonhuman primates requires an understanding of the role of the UL/b′ proteins in the viral life cycle and mandates rigorous vaccine trials that will encompass the challenges expected during human HCMV vaccine trials.

The mechanistic basis by which HCMV is secreted into bodily fluids is relatively unexplored. After host entry, HCMV infects multiple cell types and tissues systemically, thereby establishing latently infected reservoirs that support a lifelong persistent infection. HCMV is periodically shed in fluids derived from oropharyngeal, mammary, and urogenital mucosae, tissues that are predominantly comprised of myoepithelial and ductal epithelial cells and endothelial cell-lined vasculature. The importance of seeding these sites with virus is highlighted by the natural history of HCMV; >99% of primary HCMV infections result from horizontal transfer of infectious virus in bodily fluids from an infected to an uninfected host. Multiple studies have demonstrated that a viral protein complex composed of UL128, UL130, and UL131, together with gH and gL (the UL128 complex), is obligatory for efficient in vitro infection of epithelial and endothelial cells but is not required for infection of fibroblasts (2, 32, 39, 50, 62, 63, 75). Similar findings have been shown for the orthologous ORF in RhCMV (43). Whereas RhCMV 68-1 cannot productively infect rhesus retinal pigment epithelial cells, repair of the RhUL128-RhUL131 locus in bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-derived 68-1 restored replication efficiency in this cell type (43). In addition, only RhCMV strains with an intact RhUL128 complex, including UCD52 and UCD59, can productively infect primary monkey kidney epithelial cells (Y. Yue and P. A. Barry, unpublished observations). Taken together, observations in vitro and the results herein suggest that an important in vivo correlate of the in vitro phenotype of epithelial and endothelial cell tropism may be efficient systemic dissemination of RhCMV to establish viral reservoirs and sustained shedding of high-titer virus in mucosal fluids. Conversely, in 68-1, the absence of epithelial and endothelial cell tropism is associated with a greatly reduced potential for viral dissemination and excretion into bodily fluids. Whereas UCD52 and UCD59 were detected in multiple tissues in coinoculated animals, the limited spread of RhCMV 68-1 to distal sites beyond the site of inoculation is most likely due to infection of fibroblasts and other nonepithelial/nonendothelial cell types.

In addition to the RhUL128 complex, there are other ORF within the UL/b′ region of RhCMV that may influence shedding patterns by facilitating viral dissemination from the site of inoculation to sites of shedding. UCD52 and UCD59, like wild-type RhCMV, encode six ORF, each of which has an ELRCXC-related motif, a hallmark of alpha (CXC)-chemokines (48). Although these RhCMV ORF have not been functionally characterized, CXC chemokines, including the UL146 proteins of HCMV and chimpanzee CMV, signal chemotaxis primarily of neutrophils (47, 51). In 68-1, three CXC-like ORF (rh161.1, RhUL146a, and RhUL146b) have been deleted, and two others (RhUL147 and RhUL146, both orthologs of the corresponding HCMV ORF) are inverted in relation to their orientation in wild-type RhCMV as a result of the genomic rearrangement within UL/b′. The product of the sixth CXC-like ORF (rh161.2) has been truncated by 13 to 25 amino acids, compared to sequences of wild-type strains. Although the contribution of CXC chemokines to the life cycle of primate CMV is not resolved, there is evidence that HCMV hijacks neutrophils as vehicles for viral dissemination. HCMV antigens can be detected in circulating neutrophils during both primary infection and clinically apparent cases of reactivated virus (27, 36, 45, 52, 60, 66, 73). Current models describing the presence of HCMV in leukocytes are based on in vitro studies and involve initial chemo-attraction of circulating leukocytes to sites of infection by the viral UL146 protein (51). Following microfusion between infected endothelial cells and leukocytes, there is direct intercellular transport of progeny virions from the endothelial cells to the leukocytes, which can serve as a “Trojan horse” for transport of nonreplicating virus particles to other sites (19, 26, 31, 32, 59, 60). Notably, intercellular transfer of HCMV occurs only when UL128 complex-positive strains are used and not with laboratory-adapted strains lacking a functional UL128 complex (59, 60). This model invokes the synergism of a combined chemo-attraction of neutrophils to sites of infection and a subsequent UL128 complex-mediated transfer to neutrophils to enable spread of the virus from the initial site of infection. A similar strategy is used by both murine and rat CMVs in which viral beta-chemokines (m131-129 and r131, respectively) stimulate a mononuclear, versus a polymorphonuclear, inflammatory response at the site of infection to enable viral dissemination to salivary glands via transfer within recruited macrophages (25, 42, 64, 65). Subcutaneous inoculation of monkeys with RhCMV 68-1 similarly stimulates a mononuclear cell infiltrate (1), which stands in contrast to a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate in animals inoculated with RhCMV UCD52 or UCD59 (B. Assaf and P. A. Barry, unpublished observations). Based on accumulating evidence, the CXC chemokines in primate CMV might also be considered determinants for shedding by their influence on the kinetics and magnitude of viral seeding of distal tissues.

This study also revealed several strategies that can be used to further optimize nonhuman primate vaccine studies in a stepwise manner to reflect the many variables that affect vaccine outcomes following exposure of immunized humans to HCMV. Challenges facing HCMV vaccine clinical trials potentially include repeated exposures to differing titers of antigenically variant viruses across different mucosal surfaces. One strategy that has been used is to challenge vaccinated macaques by parenteral inoculation of a defined titer of virus and compare the levels of viral replication in unvaccinated controls and challenged animals (1, 77, 79). While subcutaneous or intravenous challenges are not natural routes of exposure, both offer the advantage of delivering a defined titer of virus at a specific time postvaccination. However, parenteral inoculation sets a high threshold for a vaccine to absolutely block (completely abrogate) viral replication and does not evaluate any protective effect of mucosal immunity. A relevant challenge would deliver virus directly to a mucosal surface, such as the buccal cavity, to mimic mucosal exposure, although this requires determination of a virologically relevant titer of challenge virus that approximates titers of horizontally transmitted virus. Vaccine challenge studies can also be designed to take advantage of the natural history of RhCMV in cohoused macaques, which entails frequent interactions in a dynamic social structure where RhCMV is likely transmitted through contact with urine, by sexual activity, and across mucosae by means of exchanged saliva during grooming activity, from shared water sources, or from puncture wounds during fighting. As demonstrated by our small-cohort study, contact between naïve and RhCMV-excreting animals leads to relatively rapid horizontal transmission of virus, even in sexually immature juveniles. Future studies can be designed where vaccine and control groups are cohoused with animals that are shedding virus to enable repeated mucosal exposure to antigenically diverse RhCMV variants, thereby modeling the high threshold of protection required of an HCMV vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health to P.A.B. (grants AI063356 and AI49342), the California National Primate Research Center (grant RR000169), and the Margaret M. Deterding Infectious Disease Research Support Fund to P.A.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abel K., et al. 2008. A heterologous DNA prime/protein boost immunization strategy for rhesus cytomegalovirus. Vaccine 26:6013–6025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adler B., et al. 2006. Role of human cytomegalovirus UL131A in cell type-specific virus entry and release. J. Gen. Virol. 87:2451–2460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adler S. P. 1991. Cytomegalovirus and child day care: risk factors for maternal infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:590–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adler S. P. 1991. Molecular epidemiology of cytomegalovirus: a study of factors affecting transmission among children at three day-care centers. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:584–590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adler S. P. 1986. Molecular epidemiology of cytomegalovirus: evidence for viral transmission to parents from children infected at a day care center. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 5:315–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akter P., et al. 2003. Two novel spliced genes in human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1117–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alcendor D. J., Barry P. A., Pratt-Lowe E., Luciw P. A. 1993. Analysis of the rhesus cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter. Virology 194:815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alford C. A., Britt W. J. 1993. Cytomegalovirus, p. 227–255 In Roizman B., Whitley R. J., Lopez C. (ed.), The human herpesviruses. Raven Press, Ltd., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andrade M. R., et al. 2003. Prevalence of antibodies to selected viruses in a long-term closed breeding colony of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) in Brazil. Am. J. Primatol. 59:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arora N., Novak Z., Fowler K. B., Boppana S. B., Ross S. A. 2010. Cytomegalovirus viruria and DNAemia in healthy seropositive women. J. Infect. Dis. 202:1800–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barry P. A., Chang W.-L. W. 2007. Primate betaherpesviruses, p. 1051–1075 In Arvin A., et al. (ed.), Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barry P. A., Strelow L. 2008. Development of breeding populations of rhesus macaques that are specific pathogen free for rhesus cytomegalovirus. Comp. Med. 58:43–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bradley A. J., et al. 2009. High-throughput sequence analysis of variants of human cytomegalovirus strains Towne and AD169. J. Gen. Virol. 90:2375–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cannon M. J., Schmid D. S., Hyde T. B. 2010. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 20:202–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang W., Barry P. 2010. Attenuation of innate immunity by cytomegalovirus IL-10 establishes a long-term deficit of adaptive antiviral immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:22647–22652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang W. L., Kirchoff V., Pari G. S., Barry P. A. 2002. Replication of rhesus cytomegalovirus in life-expanded rhesus fibroblasts expressing human telomerase. J. Virol. Methods 104:135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheung T. C., et al. 2005. Evolutionarily divergent herpesviruses modulate T cell activation by targeting the herpesvirus entry mediator cosignaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:13218–13223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Colugnati F. A., Staras S. A., Dollard S. C., Cannon M. J. 2007. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect. Dis. 7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Craigen J. L., et al. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus infection up-regulates interleukin-8 gene expression and stimulates neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology 92:138–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dargan D. J., et al. 2010. Sequential mutations associated with adaptation of human cytomegalovirus to growth in cell culture. J. Gen. Virol. 91:1535–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davison A. J., et al. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus genome revisited: comparison with the chimpanzee cytomegalovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 84:17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dollard S. C., Grosse S. D., Ross D. S. 2007. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 17:355–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elek S. D., Stern H. 1974. Development of a vaccine against mental retardation caused by cytomegalovirus infection in utero. Lancet i:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fang F. Q., et al. 2009. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection in Shanghai, China. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1700–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fleming P., et al. 1999. The murine cytomegalovirus chemokine homolog, m131/129, is a determinant of viral pathogenicity. J. Virol. 73:6800–6809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gerna G., et al. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus replicates abortively in polymorphonuclear leukocytes after transfer from infected endothelial cells via transient microfusion events. J. Virol. 74:5629–5638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerna G., et al. 1992. Human cytomegalovirus infection of the major leukocyte subpopulations and evidence for initial viral replication in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from viremic patients. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1236–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodrum F., Reeves M., Sinclair J., High K., Shenk T. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus sequences expressed in latently infected individuals promote a latent infection in vitro. Blood 110:937–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griffiths P. D. 2002. Strategies to prevent CMV infection in the neonate. Semin. Neonatol. 7:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Griffiths P. D., McLean A., Emery V. C. 2001. Encouraging prospects for immunisation against primary cytomegalovirus infection. Vaccine 19:1356–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grundy J. E., Lawson K. M., MacCormac L. P., Fletcher J. M., Yong K. L. 1998. Cytomegalovirus-infected endothelial cells recruit neutrophils by the secretion of C-X-C chemokines and transmit virus by direct neutrophil-endothelial cell contact and during neutrophil transendothelial migration. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1465–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hahn G., et al. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J. Virol. 78:10023–10033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hansen S. G., et al. 2010. Evasion of CD8+ T cells is critical for superinfection by cytomegalovirus. Science 328:102–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hansen S. G., Strelow L. I., Franchi D. C., Anders D. G., Wong S. W. 2003. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of rhesus cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 77:6620–6636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hansen S. G., et al. 2009. Effector memory T cell responses are associated with protection of rhesus monkeys from mucosal simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. Nat. Med. 15:293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Holland G. N., et al. 1983. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ocular manifestations. Ophthalmology 90:859–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huff J. L., Eberle R., Capitanio J., Zhou S.-S., Barry P. A. 2003. Differential detection of B virus and rhesus cytomegalovirus in rhesus macaques. J. Gen. Virol. 84:83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Isaacson M. K., Compton T. 2009. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B is required for virus entry and cell-to-cell spread but not for virion attachment, assembly, or egress. J. Virol. 83:3891–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jarvis M. A., Nelson J. A. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus tropism for endothelial cells: not all endothelial cells are created equal. J. Virol. 81:2095–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones-Engel L., et al. 2006. Temple monkeys and health implications of commensalism, Kathmandu, Nepal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:900–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Just M., Buergin-Wolff A., Emoedi G., Hernandez R. 1975. Immunisation trials with live attenuated cytomegalovirus TOWNE 125. Infection 3:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaptein S. J., et al. 2004. The r131 gene of rat cytomegalovirus encodes a proinflammatory CC chemokine homolog which is essential for the production of infectious virus in the salivary glands. Virus Genes 29:43–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lilja A. E., Shenk T. 2008. Efficient replication of rhesus cytomegalovirus variants in multiple rhesus and human cell types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19950–19955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marshall B. C., Adler S. P. 2009. The frequency of pregnancy and exposure to cytomegalovirus infections among women with a young child in day care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200:163.e1–163.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martin D. C., Katzenstein D. A., Yu G. S., Jordan M. C. 1984. Cytomegalovirus viremia detected by molecular hybridization and electron microscopy. Ann. Intern. Med. 100:222–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McCormick A. L., Skaletskaya A., Barry P. A., Mocarski E. S., Goldmacher V. S. 2003. Differential function and expression of the viral inhibitor of caspase 8-induced apoptosis (vICA) and the viral mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) cell death suppressors conserved in primate and rodent cytomegaloviruses. Virology 316:221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miller-Kittrell M., Sai J., Penfold M., Richmond A., Sparer T. E. 2007. Functional characterization of chimpanzee cytomegalovirus chemokine, vCXCL-1(CCMV). Virology 364:454–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oxford K. L., et al. 2008. Protein coding content of the U(L)b′ region of wild-type rhesus cytomegalovirus. Virology 373:181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pass R. F., et al. 2009. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1191–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Patrone M., et al. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus UL130 protein promotes endothelial cell infection through a producer cell modification of the virion. J. Virol. 79:8361–8373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Penfold M. E. T., et al. 1999. Cytomegalovirus encodes a potent α chemokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9839–9844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pepose J. S., Holland G. N., Nestor M. S., Cochran A. J., Foos R. Y. 1985. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: pathogenic mechanisms of ocular disease. Ophthalmology 92:472–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Plotkin S. A., Furukawa T., Zygraich N., Huygelen C. 1975. Candidate cytomegalovirus strain for human vaccination. Infect. Immun. 12:521–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Plotkin S. A., Huang E. S. 1985. Cytomegalovirus vaccine virus (Towne strain) does not induce latency. J. Infect. Dis. 152:395–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Plotkin S. A., Starr S. E., Friedman H. M., Gonczol E., Weibel R. E. 1989. Protective effects of Towne cytomegalovirus vaccine against low-passage cytomegalovirus administered as a challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 159:860–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Price D. A., et al. 2008. Induction and evolution of cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T cell clonotypes in rhesus macaques. J. Immunol. 180:269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Prod'homme V., et al. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus UL141 promotes efficient downregulation of the natural killer cell activating ligand CD112. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2034–2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Quinnan G. V. J., et al. 1984. Comparative virulence and immunogenicity of the Towne strain and a nonattenuated strain of cytomegalovirus. Ann. Int. Med. 101:478–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Revello M. G., Gerna G. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus tropism for endothelial/epithelial cells: scientific background and clinical implications. Rev. Med. Virol. 20:136–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Revello M. G., et al. 1998. Human cytomegalovirus in blood of immunocompetent persons during primary infection: prognostic implications for pregnancy. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1170–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rivailler P., Kaur A., Johnson R. P., Wang F. 2006. Genomic sequence of rhesus cytomegalovirus 180.92: insights into the coding potential of rhesus cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 80:4179–4182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ryckman B. J., Jarvis M. A., Drummond D. D., Nelson J. A., Johnson D. C. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells depends on genes UL128 to UL150 and occurs by endocytosis and low-pH fusion. J. Virol. 80:710–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ryckman B. J., et al. 2008. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J. Virol. 82:60–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Saederup N., Aguirre S. A., Sparer T. E., Bouley D. M., Mocarski E. S. 2001. Murine cytomegalovirus CC chemokine homolog MCK-2 (m131-129) is a determinant of dissemination that increases inflammation at initial sites of infection. J. Virol. 75:9966–9976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saederup N., Mocarski E. S., Jr 2002. Fatal attraction: cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine homologs. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 269:235–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saltzman R. L., Quirk M. R., Jordan M. C. 1988. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection. Molecular analysis of virus and leukocyte interactions in viremia. J. Clin. Invest. 81:75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sequar G., et al. 2002. Experimental coinfection of rhesus macaques with rhesus cytomegalovirus and simian immunodeficiency virus: pathogenesis. J. Virol. 76:7661–7671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sinzger C., Digel M., Jahn G. 2008. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 325:63–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Spaderna S., et al. 2005. Deletion of gpUL132, a structural component of human cytomegalovirus, results in impaired virus replication in fibroblasts. J. Virol. 79:11837–11847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stanton R. J., et al. 2010. Reconstruction of the complete human cytomegalovirus genome in a BAC reveals RL13 to be a potent inhibitor of replication. J. Clin. Invest. 120:3191–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tarantal A. F., et al. 1998. Neuropathogenesis induced by rhesus cytomegalovirus in fetal rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J. Infect. Dis. 177:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tomasec P., et al. 2005. Downregulation of natural killer cell-activating ligand CD155 by human cytomegalovirus UL141. Nat. Immunol. 6:181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van der Bij W., et al. 1988. Comparison between viremia and antigenemia for detection of cytomegalovirus in blood. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2531–2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vogel P., Weigler B. J., Kerr H., Hendrickx A., Barry P. A. 1994. Seroepidemiologic studies of cytomegalovirus infection in a breeding population of rhesus macaques. Lab. Anim. Sci. 44:25–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang D., Shenk T. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:18153–18158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wills M. R., et al. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus encodes an MHC class I-like molecule (UL142) that functions to inhibit NK cell lysis. J. Immunol. 175:7457–7465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yue Y., et al. 2007. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing rhesus cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B, phosphoprotein 65-2, and viral interleukin-10 in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 81:1095–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yue Y., Kaur A., Zhou S. S., Barry P. A. 2006. Characterization and immunological analysis of the rhesus cytomegalovirus homologue (Rh112) of the human cytomegalovirus UL83 lower matrix phosphoprotein (pp65). J. Gen. Virol. 87:777–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yue Y., et al. 2008. Evaluation of recombinant modified vaccinia Ankara virus-based rhesus cytomegalovirus vaccines in rhesus macaques. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yue Y., Zhou S. S., Barry P. A. 2003. Antibody responses to rhesus cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B in naturally infected rhesus macaques. J. Gen. Virol. 84:3371–3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zanghellini F., Boppana S. B., Emery V. C., Griffiths P. D., Pass R. F. 1999. Asymptomatic primary cytomegalovirus infection: virologic and immunologic features. J. Infect. Dis. 180:702–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]