Abstract

It has long been observed that repressive signals from the neural tube block cardiogenesis in vertebrates. Here we show that a signal from the neural tube that blocks cardiogenesis in the adjacent anterior paraxial mesoderm of stage 8–9 chick embryos can be mimicked by ectopic expression of either Wnt-3a or Wnt-1, both of which are expressed in the dorsal neural tube. Repression of cardiogenesis by the neural tube can be overcome by ectopic expression of a secreted Wnt antagonist. On the basis of both in vitro and in vivo results, we propose that Wnt signals from the neural tube normally act to block cardiogenesis in the adjacent anterior paraxial mesendoderm.

Keywords: Heart formation, cardiogenesis, Wnts

Prior studies have indicated that signals from the neural tube suppress heart formation in adjacent tissue (Jacobson 1960, 1961; Climent et al. 1995; Schultheiss et al. 1997; Raffin et al. 2000). Jacobson first noted that cardiogenesis in explants of precardiac tissue from newt embryos was significantly inhibited by the presence of the neural tube (Jacobson 1960, 1961).

In contrast, anterior endoderm has heart-inducing properties, as demonstrated by the ability of this tissue to promote heart formation in coculture with posterior primitive streak, a tissue normally fated to form blood (Schultheiss et al. 1995). Thus, extirpation of the endoderm blocked heart formation in gastrula-stage newt embryos, whereas extirpation of both the endoderm and neural plate restored heart formation (Jacobson 1960, 1961). This work suggests that the neural tube secretes a signal that inhibits cardiac differentiation in neighboring mesoderm.

In addition to a heart-promoting signal from the anterior endoderm, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) expressed in lateral endoderm and ectoderm are also required for heart formation in chick embryos (Schultheiss et al. 1997; Schlange et al. 2000). Administration of BMP-2 induces cardiogenesis in explants of anterior medial mesendoderm from stage 6 chick embryos, as assayed by the expression of the cardiac regulators Nkx-2.5, GATA-4, GATA-5, GATA-6, MEF2, eHAND, and dHAND and the cardiac structural gene, ventricular myosin heavy chain (vMHC; Schultheiss et al. 1997; Schlange et al. 2000). However, when the adjacent neural tube and notochord was included in these explants, BMP-2 administration could only induce the expression of Nkx-2.5 and failed to induce the expression of either GATA-4 or vMHC (Schultheiss et al. 1997). Similarly, in vivo implantation of BMP-2-soaked beads between the neural plate and the anterior medial mesendoderm of stage 6 chick embryos induced robust ectopic expression of Nkx-2.5 but only trace levels of ectopic GATA-4 and no detectable ectopic vMHC (Schultheiss et al. 1997). These findings suggest that the heart-promoting activities of the anterior endoderm and BMPs are antagonized by repressive signals from the axial tissues that block cardiogenesis in the anterior paraxial mesoderm.

Results and Discussion

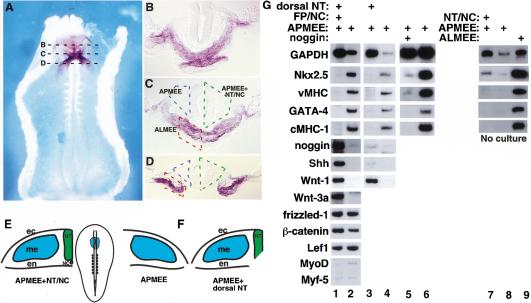

Because prior work has suggested that signals from the neural tube may block cardiogenesis, we sought to determine if signals from the neural tube also inhibit cardiogenesis in anterior paraxial mesendoderm in stage 9 chick embryos. Figure 1, panels A–D, illustrates the relative positions of tissues employed in this study. While the ventrally located heart-forming mesoderm and pharyngeal endoderm both express Nkx-2.5, the more dorsal anterior paraxial mesoderm, which lies adjacent to the neural tube, does not express this gene (Fig. 1, panels A–D). We dissected anterior paraxial mesendoderm and ectoderm (APMEE; Fig. 1C) from stage 8–9 chick embryos and cultured this tissue either alone or in the presence of the adjacent neural tube and notochord (Fig. 1E). When cultured in the presence of the axial tissues, APMEE explants neither beat nor expressed the cardiac markers Nkx-2.5, GATA-4, vMHC, and cMHC-1 (Fig. 1G, lane 1). The latter gene is a chick myosin heavy-chain isoform expressed exclusively within the heart (Croissant et al. 2000). In contrast, when cultured in the absence of the neural tube and notochord, APMEE explants underwent cardiac differentiation, as evidenced by beating in ∼25% of such explants (n = 80) and displayed robust expression of Nkx-2.5, GATA-4, vMHC, and cMHC-1 transcripts in nearly all such explants (Fig. 1G, lanes 2,4,6). Although anterior paraxial mesoderm is fated to give rise to both head mesenchyme and skeletal muscles (Christ and Ordahl 1995), the skeletal muscle regulators, MyoD and Myf-5, were not expressed in APMEE explants that expressed cardiac markers after 48 h culture in vitro (Fig. 1G, lane 2). Thus, after 48 h in culture, explanted APMEE gives rise to cardiac but not skeletal muscle tissue. At the time of dissection, explants of APMEE tissue expressed only trace levels of Nkx-2.5 and no detectable levels of GATA-4, vMHC, or cMHC-1 (Fig. 1G, lanes 7,8), whereas explants of anterior lateral mesendoderm plus ectoderm (ALMEE), which includes the heart-forming region, expressed abundent levels of these transcripts (Fig. 1G, lane 9). These findings imply that removal of the APMEE from the repressive influence of the axial tissues allowed this tissue to activate the cardiac myocyte-differentiation program in vitro.

Figure 1.

Signals from the dorsal neural tube block cardiogenesis in anterior paraxial mesendoderm. (A) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Nkx-2.5 in a stage 9 chick embryo (ventral side up). (B–D) show representative transverse sections as indicated in A. Anterior paraxial mesendoderm with overlying ectoderm (APMEE) is outlined in blue, APMEE with adjacent neural tube and notochord is outlined in green, and the anterior lateral mesendoderm with overlying ectoderm (ALMEE) is outlined in red. (E) A diagram of a stage 9 chick embryo is shown in the middle panel, and the APMEE is indicated by blue shading. Diagrams of transverse sections through APMEE explants cultured in either the presence or the absence of the axial tissues are shown on the left and right, respectively. (F) Diagram of APMEE explant cultured in the presence of only the dorsal neural tube. (G) RT–PCR analysis of gene expression in explants of APMEE that have been cultured in vitro for 48 h in either the presence (lane 1) or the absence (lane 2) of the adjacent axial tissues or cultured in the presence (lane 3) or the absence (lane 4) of only the dorsal neural tube. Cardiogenesis was observed in 33 of 48 APMEE explants cultured in the absence of the axial tissues and was never observed in APMEE explants cultured in the presence of the axial tissues. APMEE explants were cultured in either the presence (lane 5) or absence (lane 6) of the BMP antagonist, noggin. Noggin administration blocked cardiogenesis in 10 out of 14 APMEE explants. Alternatively, explants of APMEE plus the neural tube and notochord (lane 7), APMEE alone (lane 8), or anterior lateral mesendoderm plus ectoderm (ALMEE; lane 9) were dissected and immediately harvested for RNA. Transcript levels of the indicated genes were monitored by RT–PCR analysis. Similar results were obtained in four independent experiments.

To define the source of the repressive signal(s) that blocks cardiac myogenesis in APMEE tissue, we cultured APMEE explants with dorsolateral neural tube, lacking the floor plate and notochord (illustrated in Fig. 1F). Cardiogenesis was similarly inhibited in APMEE explants cocultured with the neural tube in either the presence or absence of the ventral midline tissues (Fig. 1G, lanes 1 and 3, respectively). Thus, signals from the dorsolateral neural tube are sufficient to inhibit cardiogenesis in APMEE explants. Because removal of the ventral midline tissues eliminates the source of the BMP-antagonist, noggin, and Shh in these explants, these results suggest that other signals from the axial tissues repress heart formation. Nonetheless, administration of the BMP-antagonist noggin was sufficient to inhibit cardiogenesis in APMEE explants (Fig. 1G, lane 5), consistent with prior findings that heart formation requires BMP signaling (Schultheiss et al. 1997; Schlange et al. 2000). Thus, we conclude that in addition to noggin, which is expressed in the notochord, another signal expressed in the dorsal neural tube also blocks heart formation in APMEE tissue.

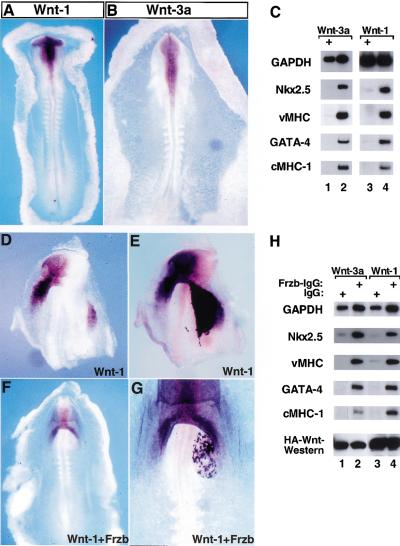

Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a are expressed in the open neural plate and dorsal neural tube adjacent to the anterior paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 2, panels A,B). These signaling molecules are highly expressed in explants containing both the APMEE and the neural tube but are not significantly expressed in AMPEE explants when cultured alone (Fig. 1G, lanes 1,2). In addition to expression of Wnt family members in the neural tube, we detected expression of Frizzled-1, β-catenin, and Lef1, all of which are components of the Wnt signaling cascade, in APMEE explants (Fig. 1G, lanes 1,2). Because Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a are expressed in the neural tube that lies adjacent to the AMPEE, we assayed whether these Wnt family members could mimic the inhibitory effects of the neural tube on cardiogenesis. Stage 9 APMEE explants were infected with avian retroviral vectors encoding either Wnt-3a (RCAS-Wnt-3a) or alkaline phosphatase (RCAS-AP) as a control (Fig. 2C, lanes 1,2). Alternatively, Rat-1 cells stably overexpressing Wnt-1 or parental Rat-1 fibroblasts were cocultured with APMEE explants (Fig. 2C, lanes 3,4). In the absence of ectopic Wnt administration, these explants underwent full cardiac differentiation (Fig. 2C, lanes 2,4). In contrast, APMEE explants exposed to either Wnt-3a or Wnt-1 failed to activate expression of any cardiac markers (Fig. 2C, lanes 1,3). In addition, implantation of fibroblasts expressing Wnt-1 into one side of the heart-forming region of stage 7 chick embryos blocked subsequent expression of Nkx-2.5 (Fig. 2, panels D,E). These findings indicate that Wnt signals are potent inhibitors of cardiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of cardiogenesis by Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a. Expression of Wnt-1 (A) and Wnt-3a (B) as assessed by whole-mount in situ hybridization in stage 9–10 chick embryos. (C) Stage 9 APMEE explants were infected with either RCAS–Wnt-3a (lane 1) or RCAS–AP (lane 2). Rat-1/Wnt-1-HA cells (lane 3) or Rat-1 control cells (lane 4) were cocultured with APMEE explants on raft filters. Wnt-3a expression blocked cardiogenesis in ∼70% of the APMEE explants (n = 24), whereas Wnt-1 expression blocked cardiogenesis in 50% of such cultures (n = 12). (D–G) Rat-1/Wnt-1 cells were transiently transfected with either a control IgG expression vehicle (D,E) or a Frzb–IgG expression vehicle (F,G). Cell pellets were implanted into the left side of the heart-forming region of a stage 7 chick embryo that was maintained in New culture. Embryos were allowed to developed to stage 9–10, and subsequently analyzed by whole-mount in situ hybridization for Nkx-2.5 gene expression (D,F). Following in situ hybridization, the embryos were subsequently immunostained for IgG to identify the location of the IgG- or the Frzb–IgG-expressing cell pellet (E,G). The IgG- or the Frzb–IgG-expressing cells stain darker purple than cells expressing Nkx-2.5 as detected by in situ hybridization in D and F. (H) APMEE explants were cultured either with Rat-1/Wnt-3a-HA cells (lanes 1,2) or Rat-1/Wnt-1-HA cells (lanes 3,4) that had been transiently transfected with either control IgG (lanes 1,3) or with Frzb–IgG (lanes 2,4). After 48 h in culture, RNA was harvested and transcript levels of the indicated genes were monitored by RT–PCR analysis. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Western blot analysis of the expression levels of the HA-tagged Wnts is shown.

Wnt signals are transduced by members of the Frizzled receptor family, which contains seven-transmembrane domains and an extracellular cysteine-rich domain (CRD) that interacts with the Wnt ligand (Bhanot et al. 1996). A family of soluble Frizzled-related secreted proteins (Sfrp; also known as Frzb/Sarp) share the Frizzled CRD domain but not the transmembrane domains and have been demonstrated to block Wnt signaling (Leyns et al. 1997; Rattner et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1997). We have fused one such chick Sfrp with the Fc region of IgG, to generate a reagent (termed Frzb–IgG) that blocks both Wnt-3a and Wnt-1 signaling (see below). Cardiogenesis was blocked in APMEE explants cocultured with fibroblasts expressing either Wnt-3a or Wnt-1 that had been transfected with the IgG expression vehicle (Fig. 2H, lanes 1,3). In contrast, cardiogenesis took place in APMEE explants cocultured with Wnt-expressing fibroblasts that had been transiently transfected with an expression vehicle encoding Frzb–IgG (Fig. 2H, lanes 2,4). Importantly, transfection of Frzb–IgG did not alter the levels of Wnt produced by the fibroblasts (Fig. 2H, lanes 1–4). Transfection of Frzb–IgG into Wnt-1-expressing fibroblasts similarly blocked the ability of these cells to extinguish Nkx-2.5 gene expression in vivo (Fig. 2, panels F,G). Thus, expression of the Frzb–IgG fusion is capable of blocking the ability of either Wnt-1 or Wnt-3a to inhibit cardiogenesis in APMEE tissue either in vitro or in vivo.

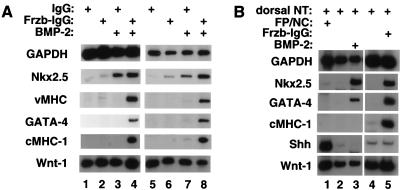

To address whether Wnt signals from the neural tube block cardiogenesis in the anterior paraxial mesendoderm, we cultured explants containing both APMEE and the neural tube and notochord (as shown schematically in Fig. 1E) with either control IgG, Frzb–IgG alone, BMP-2 alone, or the combination of Frzb–IgG and BMP-2. No cardiac markers were detected in explants exposed to either soluble IgG (Fig. 3A, lane 1) or to IgG expressing cells (Fig. 3A, lane 5). Addition of either soluble Frzb–IgG (Fig. 3A, lane 2) or Frzb–IgG-expressing cells (Fig. 3A, lane 6) to these cultures induced only trace levels of Nkx-2.5 yet failed to induce either GATA-4 or vMHC. Addition of BMP-2 alone induced higher levels of Nkx-2.5 but, similarly, failed to induce expression of either GATA-4 or vMHC (Fig. 3A, lanes 3,7), consistent with previous findings (Schultheiss et al. 1997). In striking contrast, addition of the combination of either soluble Frzb–IgG- or Frzb–IgG-expressing cells plus BMP-2 induced expression of Nkx-2.5, GATA-4, vMHC, and cMHC-1 in cultures containing the APMEE and the axial tissues (Fig. 3A, lanes 4,8). Cardiac gene expression was limited to the APMEE cells in these cultures, as neural tube cultured in the presence of Frzb–IgG plus BMP-2 failed to express any cardiac marker genes (data not shown). These findings indicate that signals from the axial tissues that block cardiogenesis in the anterior paraxial mesoderm can be reversed by the combination of a Wnt antagonist working in concert with BMP signals.

Figure 3.

A combination of BMP signals and Frzb promotes cardiogenesis in anterior paraxial mesendoderm in the presence of the neural tube and notochord. (A) Stage 8 APMEE plus the adjacent neural tube and notochord (schematically illustrated in Fig. 1E) were dissected. Explants were cultured in the presence of either soluble control IgG (lanes 1,3) or soluble Frzb–IgG (lanes 2,4) in either the absence (lanes 1,2) or presence (lanes 3,4) of 60 ng/mL BMP-2. Alternatively, APMEE plus neural tube and notochord explants were cocultured on raft filters with aggregates of 293 cells transfected with either a control IgG expression vehicle (lanes 5,7) or a Frzb–IgG expression vehicle (lanes 6,8) and cultured either in the absence (lanes 5,6) or the presence (lanes 7,8) of 60 ng/mL BMP-2. After 48 h in culture, RNA was harvested and transcript levels monitored by RT–PCR. (B) Analysis of gene expression in APMEE explants that have been cultured in the presence of either the dorsal neural tube plus the floor plate and notochord (lane 1) or the dorsal neural tube only (lanes 2–5; schematically illustrated in Fig. 1F). Explants were cultured in the presence of exogenous BMP-2 or Frzb–IgG (lanes 3 and 5, respectively). Similar results have been obtained in four independent experiments.

Although the dorsal neural tube expresses several BMP family members (Liem et al. 1995), we found that Frzb–IgG could only elicit cardiogenesis in APMEE cultured with the axial tissues in the presence of exogenous BMP-2. We speculated that the requirement of both exogenous BMP and Frzb–IgG to promote cardiogenesis in these cultures may be because of the expression of the BMP-antagonists, noggin, and chordin in the notochord. Therefore, we tested whether cardiogenesis in APMEE explants cultured solely with the dorsal neural tube could be elicited by administration of Frzb–IgG alone. Indeed, administration of Frzb–IgG to APMEE cultured with only the dorsal neural tube induced a robust cardiogenic response in the absence of exogenous BMP-2 (Fig. 3B, lane 5). In parallel cultures, BMP-2 administration induced GATA-4 and Nkx2.5 yet failed to elicit expression of cMHC-1 (Fig. 3B, lane 3). Thus, signals from the dorsal neural tube that suppress cardiogenesis in the adjacent APMEE can be completely reversed by administration of the Wnt antagonist Frzb–IgG.

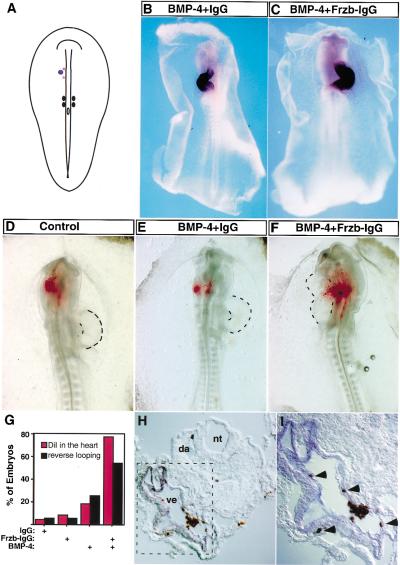

Our results with in vitro explant cultures suggest that Wnt signals from the dorsal neural tube work together with BMP-antagonists from the notochord to block ectopic cardiogenesis in anterior paraxial mesoderm. To test if such is the case in vivo, we examined whether ectopic expression of either BMP4 and/or FrzB–IgG in the anterior paraxial mesoderm could alter the fate of these cells in vivo. Pellets of 293 cells programmed to express either BMP4, FrzB–IgG, the combination of both BMP-4 and FrzB–IgG, or control IgG were implanted into the presumptive anterior paraxial mesoderm on the left side of a stage 7 chick embryo (schematically depicted in Fig. 4A) Such manipulated embryos were evaluated for Nkx-2.5 and vMHC gene expression at stages 10–14. Consistent with prior findings (Schultheiss et al. 1997; Schlange et al. 2000) and similar to our in vitro results (see above), ectopic expression of BMP-4 but not Frzb–IgG in the anterior paraxial mesoderm induced ectopic Nkx-2.5 expression in the head region (data not shown). While implantation of cells expressing only BMP-4 or Frzb–IgG into the presumptive anterior paraxial mesoderm failed to affect subsequent vMHC expression (Fig. 4B; data not shown), implantation of cells expressing the combination of BMP-4 plus Frzb–IgG resulted in increased vMHC staining in an enlarged heart (Fig. 4C). In addition, heart looping was reversed in >50% of embryos containing the BMP-4 plus Frzb–IgG cell pellets (n = 25; (Fig. 4C,G). In contrast, heart looping was not affected in embryos containing either control or Frzb–IgG cell pellets (Figures 4B,G; data not shown), and implantation of cell pellets expressing only BMP-4 led to reverse heart looping in only 20% of such manipulated embryos (n = 25; Fig. 4G). These results suggest that administration of BMP-4 plus a Wnt antagonist to the anterior paraxial mesoderm led to an increase in the pool of cardiac myocyte precursors with a corresponding enlargement of the heart. Furthermore, whereas prior studies have shown that differential BMP signaling on the left and right sides of gastrula stage chick embyros can modulate heart looping (Rodriguez Esteban et al. 1999; Yokouchi et al. 1999; Zhu et al. 1999), our findings suggest that Wnt signaling may also play a role in this process.

Figure 4.

Inhibiting Wnt signals in vivo directs anterior paraxial mesodermal cells into the cardiac fate. (A) Pellets of cells expressing BMP-4, Frzb–IgG, and/or control IgG were implanted into the left side of the anterior paraxial mesoderm in stage 7 chick embryos. The location of the cell pellet is represented by a blue dot. In some cases, DiI was subsequently injected into a region that lay medial to the implanted cell pellet (red stars). The embryo is depicted dorsal side up. (B,C) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for vMHC expression is shown in stage 12 embryos that had been previously implanted with cell pellets expressing BMP-4 plus control IgG (B) or the combination of Frzb–IgG and BMP-4 (C). (D–F) Examples of the results obtained from DiI-injected embryos; dorsal side up. HEK-293 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were implanted as described in A. Embryos were allowed to developed to stage 12–13 (26–30 h) before fixation. Brightfield and fluorescent images were taken and are overlayed. (G) Statistical summary of the in vivo results (red, DiI tracing; black, heart looping). (H,I) Implanting Frzb–IgG- and BMP-4-expressing cells into the anterior paraxial mesoderm induces migration of cells within this tissue into regions of the heart that express vMHC. Transverse section of embryo implanted with Frzb–IgG- and BMP-4-expressing cells in the anterior paraxial mesoderm (as shown in F). DiI fluorescence signals were photoconverted into a brown precipitate before in situ hybridization for vMHC. (I) High-power magnification of the square area outlined in H. DiI-labeled cells are brown (indicated by arrow heads in I); vMHC-positive cells stain blue; (nt) neural tube; (nc) notochord; (da) dorsal aorta; (ve) heart ventricle.

We speculated that the combination of BMP plus anti-Wnt signals in the presumptive anterior paraxial mesoderm may have induced the formation of an enlarged heart by converting presumptive paraxial mesodermal cells into cardiac precursors. Because cardiac precursors are known to migrate to the ventral midline under the control of sphingosine-1-phosphate (Kupperman et al. 2000), we reasoned that respecification of presumptive paraxial mesodermal cells into heart cells would result in the migration of such newly recruited cardiac myocyte precursors into the forming heart. To evaluate if implantation of cell pellets expressing BMP-4 plus Frzb–IgG caused presumptive paraxial mesoderm cells to migrate into the heart, we followed the movement of DiI-labeled head mesenchyme cells following implantation of the cell pellets (Fig. 4D–G). After implantation of transfected 293 cell pellets into the APMEE of stage 7 chick embryos, DiI was injected between the cell pellet and the midline, as illustrated in Figure 4A. Whereas in all embryos receiving the control IgG cell pellets the DiI-labeled cells remained at or close to the injection site (Fig. 4D,G; n = 23), in ∼80% of the embryos implanted with cell pellets expressing both BMP-4 plus Frzb–IgG (n = 22), the DiI-labeled cells had migrated from the head region toward, and in some cases into, the heart (Fig. 4F,G). In contrast, only 18% of embryos containing cell pellets expressing BMP-4 plus control IgG (n = 22) displayed DiI-labeled cells in the heart region (Fig. 4E,G). Thus, administration of Frzb–IgG to the presumptive head mesenchyme markedly enhanced the ability of BMP signals to induce these cells to migrate toward and into the forming heart.

To evaluate if any DiI-labeled cells in embryos that had received both BMP-4 and Frzb–IgG cell pellets expressed the cardiac marker, vMHC, we photooxidized the DiI and evaluated vMHC expression by in situ hybridization. Indeed, we observed that administration of BMP-4 plus Frzb–IgG to the presumptive head mesenchyme caused these cells to, in some cases, migrate into regions of the heart that expressed vMHC (Fig. 4H,I). Expression of vMHC was never observed in DiI-labeled cells in embryos that had received control IgG cell pellets (data not shown). These findings indicate that the combination of BMP and anti-Wnt signals can induce presumptive anterior paraxial mesodermal cells to both migrate into the heart and express a cardiac myocyte differentiation marker in vivo and are consistent with our in vitro results, suggesting that Wnt signals from the neural tube and anti-BMP signals from the notochord block cardiogenesis in this tissue (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

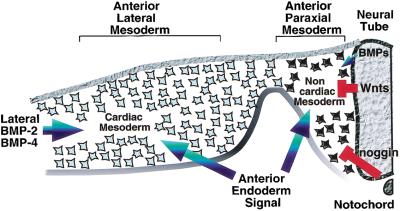

Heart formation is cued by a combination of positive and negative signals from surrounding tissues. Whereas a signal(s) from the anterior endoderm works to promote heart formation in concert with BMP signals in the anterior lateral mesoderm (blue arrows), signals from the axial tissues (red) repress heart formation in the more dorsomedial anterior paraxial mesoderm. Inhibitory signals that block heart formation in anterior paraxial mesoderm include Wnt family members expressed in dorsal neural tube (Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a) and anti-BMPs expressed in the axial tissues (i.e., noggin in the notochord). We suggest that the sum of these positive and negative signals determine the medial-lateral borders of the heart-forming region.

Our findings indicate that signals from the anterior neural tube in stage 9 chick embryos prevent ectopic cardiogenesis from occurring in anterior paraxial mesendoderm and that these signals can be mimicked by either Wnt-1 or Wnt-3a expressed in the neural tube. Whereas APMEE explants cultured alone efficiently activated the cardiac program, the cardiac program was blocked in APMEE explants when cultured in the presence of the axial tissues unless both a Wnt antagonist and BMP were added. Thus, in addition to Wnt signals from the neural tube, BMP antagonists secreted by the axial tissues, such as noggin and chordin, work in combination to repress cardiogenesis in the anterior paraxial mesoderm. We suspect that repression of cardiogenesis by signals reported to come from the neural plate or neural folds in amphibians (Jacobson 1960, 1961; Raffin et al. 2000) and the notochord in zebrafish (Goldstein and Fishman 1998) may similarly reflect the expression of either Wnts or anti-BMPs in these tissues.

In Drosophila, the BMP family member, dpp (Frasch 1995), and the Wnt family member, wingless (Wu et al. 1995), are required for the maintained expression of the NK homeobox gene tinman and for subsequent cardiogenesis. Although in vertebrates BMP signals play a positive role in promoting the expression of the NK homeobox gene, Nkx-2.5, and subsequent heart formation (Schultheiss et al. 1997; Schlange et al. 2000), our findings indicate that Wnt signals paradoxically repress heart formation in vertebrates. A simple explanation for this discrepancy is that heart precursors in flies are generated in the dorsal mesoderm, adjacent to the wingless expression domain in the ectoderm, while in vertebrates, cardiac progenitors arise in regions of low or absent Wnt signaling (Marvin et al. 2001; Schneider and Mercola 2001). This redeployment of signals to control heart development may reflect a fundamental difference between the metameric origin of the Drosophila heart precursors versus the induction of a heart field in the anterior domain of vertebrate embryos. On the basis of our prior findings, we propose that newly invaginated mesodermal cells in the anterior region of the chick embryo are uniformly exposed to a cardiac-inducing signal from the anterior endoderm (Schultheiss et al. 1995). In gastrula stage embryos, Wnt antagonists promote heart formation in the anterior lateral mesoderm, while Wnt signaling in the posterior of the embryo blocks ectopic heart formation in posterior lateral mesoderm (Marvin et al. 2001; Schneider and Mercola 2001). In neurula stage embryos, progression of cells within the cardiac field to the cardiac fate is subsequently repressed in the dorsomedial region of this field by both Wnt signals and anti-BMPs secreted by the axial tissues. Conversely, cardiogenesis is promoted in the ventrolateral region of the heart field by the presence of BMPs and the absence of Wnt signals (Fig. 5).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Explant culture conditions and retroviral reagents are described in Marvin et al. (2001). The CRD region (amino acids 24–178) of chick Frzb was cloned in-frame into the BamH1 site of the pRK5-IgG expression vector (human IgG heavy chain provided by J. Nathans, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD). Expression vehicles encoding either Frzb–IgG or control IgG were transfected into HEK-293 cells. Medium conditioned for 5 d was harvested and diluted 1 : 4 into culture medium. Alternatively, cell pellets were made from HEK-293 cells that had been transfected with either a Frzb–IgG or a control IgG expression vehicle. Noggin-conditioned medium from CHO-transfected cells (provided by R. Harland, UC Berkeley, CA) was diluted as mentioned above. Human recombinant BMP-2 (or BMP-4) was generously provided by Genetics Institute and was employed at 40–60 ng/mL. Explants were maintained in culture for 48 h unless otherwise indicated.

RT–PCR

RT–PCR was performed as described in Marvin et al. (2001). Primer sequences are available on request.

New culture and DiI experiments

Stage 6–7 chick embryos were explanted ventral side up in New culture. DiI was injected into the head mesenchyme region (Fig. 4A) as described (Psychoyos and Stern 1996). Combined DiI labeling followed by in situ hybridization was performed by photoconverting the fluorescence signal before initiating the in situ hybridization protocol as described in Nieto et al. (1995).

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Marvin and Ram Reshef for initiating the cloning of chick Frzb in our lab, Chris Tunkey for technical help, Andrew Dudley and Claudio Stern for help and advice with the DiI experiments, Jeremy Nathans for pRK5 expression vectors encoding various anti-Wnts, Cliff Tabin for RCAS-Wnt-3a, Connie Cepko for RCAS-AP, Genetics Institute and Vicky Rosen for kindly providing us with BMP-2/-4, and members of the Lassar lab for their thoughtful comments on this work. This work was supported by grants to A.B.L. from the National Institutes of Health. This work was done during the tenure of an established investigatorship from the American Heart Association to A.B.L. E.T. was a recipient of the EMBO postdoctoral long-term fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL andrew_lassar@hms.harvard.edu; FAX (617) 738-0516.

References

- Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, Hsieh JC, Wang Y, Macke JP, Andrew D, Nathans J, Nusse R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature. 1996;382:225–230. doi: 10.1038/382225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ B, Ordahl CP. Early stages of chick somite development. Anat Embryol. 1995;191:381–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00304424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Climent S, Sarasa M, Villar JM, Murillo-Ferrol NL. Neurogenic cells inhibit the differentiation of cardiogenic cells. Dev Biol. 1995;171:130–148. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croissant JD, Carpenter S, Bader D. Identification and genomic cloning of CMHC1: A unique myosin heavy chain expressed exclusively in the developing chicken heart. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1944–1951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasch M. Induction of visceral and cardiac mesoderm by ectodermal Dpp in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1995;374:464–467. doi: 10.1038/374464a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AM, Fishman MC. Notochord regulates cardiac lineage in zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol. 1998;201:247–252. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson AG. Influences of ectoderm and endoderm on heart differentiation in the newt. Dev Biol. 1960;2:138–154. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(60)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Heart determination in the newt. J Exp Zool. 1961;146:139–152. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401460204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupperman E, An S, Osborne N, Waldron S, Stainier DY. A sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor regulates cell migration during vertebrate heart development. Nature. 2000;406:192–195. doi: 10.1038/35018092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim SH, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell. 1997;88:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem KF, Jr, Tremml G, Roelink H, Jessell TM. Dorsal differentiation of neural plate cells induced by BMP-mediated signals from epidermal ectoderm. Cell. 1995;82:969–979. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin M, Rocco GD, Gardiner A, Bush S, Lassar A. Inhibition of Wnt activity induces heart formation from posterior mesoderm. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:316–327. doi: 10.1101/gad.855501. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto MA, Sechrist J, Wilkinson DG, Bronner-Fraser M. Relationship between spatially restricted Krox-20 gene expression in branchial neural crest and segmentation in the chick embryo hindbrain. EMBO J. 1995;14:1697–1710. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychoyos D, Stern CD. Restoration of the organizer after radical ablation of Hensen's node and the anterior primitive streak in the chick embryo. Development. 1996;122:3263–3273. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffin M, Leong LM, Rones MS, Sparrow D, Mohun T, Mercola M. Subdivision of the cardiac Nkx2.5 expression domain into myogenic and nonmyogenic compartments. Dev Biol. 2000;218:326–340. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner A, Hsieh JC, Smallwood PM, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nathans J. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Esteban C, Capdevila J, Economides AN, Pascual J, Ortiz A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. The novel Cer-like protein Caronte mediates the establishment of embryonic left-right asymmetry. Nature. 1999;401:243–251. doi: 10.1038/45738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlange T, Andree B, Arnold H, Brand T. BMP2 is required for early heart development during a distinct time period. Mech Dev. 2000;91:259–270. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider V, Mercola M. Wnt antagonism initiates cardigenesis in Xenopus laevis. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:304–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.855601. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss TM, Xydas S, Lassar AB. Induction of avian cardiac myogenesis by anterior endoderm. Development. 1995;121:4203–4214. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss T, Burch J, Lassar A. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:451–462. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Krinks M, Lin K, Luyten FP, Moos M., Jr Frzb, a secreted protein expressed in the Spemann organizer, binds and inhibits Wnt-8. Cell. 1997;88:757–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81922-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Golden K, Bodmer R. Heart development in Drosophila requires the segment polarity gene wingless. Dev Biol. 1995;169:619–628. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokouchi Y, Vogan KJ, Pearse RV, II, Tabin CJ. Antagonistic signaling by Caronte, a novel Cerberus-related gene, establishes left-right asymmetric gene expression. Cell. 1999;98:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Marvin MJ, Gardiner A, Lassar AB, Mercola M, Stern CD, Levin M. Cerberus regulates left-right asymmetry of the embryonic head and heart. Curr Biol. 1999;9:931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]