Abstract

During acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, there is a massive depletion of CD4+ T cells in the gut mucosa that can be reversed to various degrees with antiretroviral therapy. Th17 cells have been implicated in mucosal immunity to extracellular bacteria, and preservation of this subset may support gut mucosal immune recovery. However, this possibility has not yet been evaluated in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs), who maintain high CD4+ T cell counts and suppress viral replication in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. In this study, we evaluated the immunophenotype and function of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood and gut mucosa of HIV-uninfected controls, LTNPs, and HIV-1-infected individuals treated with prolonged antiretroviral therapy (ART) (VL [viral load]<50). We found that LTNPs have intact CD4+ T cell populations, including Th17 and cycling subsets, in the gut mucosa and a preserved T cell population expressing gut homing molecules in the peripheral blood. In addition, we observed no evidence of higher monocyte activation in LTNPs than in HIV-infected (HIV−) controls. These data suggest that, similar to nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection, LTNPs preserve the balance of CD4+ T cell populations in blood and gut mucosa, which may contribute to the lack of disease progression observed in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

One of the hallmarks of HIV infection is progressive immunodeficiency, characterized by both a quantitative and qualitative deficit of CD4+ T lymphocytes (15). A compartment where the interplay between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the host's immune system takes center stage is the gut mucosa. During acute simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and HIV infection, depletion of CD4+ T cells, both of effector and central memory phenotype, occurs in the gut mucosa before similar changes are observed in peripheral blood and other lymphoid tissues (7, 21, 27, 28, 32, 33, 45). This damage to the gut mucosa may enhance the translocation of microbial products into the systemic circulation (16). Restoration of CD4+ T cells in the gut mucosa occurs to various degrees in response to antiretroviral therapy (ART), with some individuals achieving CD4+ T cell levels similar to those of uninfected controls (10, 11, 17, 22, 29). The factors that determine the degree of restoration have yet to be fully elucidated.

Recent studies have indicated that a subset of CD4+ T cells known as Th17 cells may also play a role in HIV pathogenesis and ART-induced immune reconstitution in the gut mucosa. The Th17 cells produce interleukin 17 (IL-17), IL-22, and IL-21, which are important in the maintenance of intact epithelium and host defenses against extracellular bacteria and fungi (37). IL-22 induces the production of antibacterial defensins as well as tissue repair through effects on epithelial cells (39). In mice, IL-17 has been shown to reduce systemic dissemination of bacterial infection from the intestine (42). Similarly, the loss of Th17 cells as a result of SIV infection in macaques is associated with a blunted cytokine response to and systemic dissemination of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, a bacterial infection that is normally controlled by the local gut inflammatory response (42). Th17 cells may be preferentially depleted compared to gut Th1 cells during SIV infection, and their loss may be associated with disease progression (9). In addition, a significant loss of gut Th17 cells has been observed in untreated HIV infection (5), and gut CD4+ T cell restoration in response to therapy has been associated with enhanced Th17 cells (29). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the loss of Th17 cells in HIV infection may have a direct effect on the integrity of the gut mucosal barrier.

Translocation of microbial products from the gut in the context of HIV infection, as measured by increased plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and soluble CD14 (sCD14), an indicator of stimulation of monocytes and macrophages by LPS, has been associated with chronic CD8+ T cell activation and immunological failure in response to ART (6, 31). However, the clinical implications of this observation and how injury to the gut mucosa leads to the translocation of microbial products without overt bacteremia is unclear. Elevated levels of plasma LPS have also been observed under lymphopenic conditions other than HIV infection, such as in patients with idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia (26) and in other disease processes, such as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and hepatitis C disease progression in HIV-infected individuals (2, 8). Interestingly, SIV-infected sooty mangabeys, who remain asymptomatic and do not progress to AIDS despite high levels of plasma SIV viremia and gut CD4+ T cell depletion, do not experience microbial translocation and demonstrate a preserved Th17 population in the gut (5, 19).

This possible relationship between gut mucosal damage, subsequent microbial translocation, and the Th17 subset of gut CD4+ T cells has not been extensively studied in the subset of HIV-infected patients with durable control over HIV replication, variably termed long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs), HIV controllers, elite suppressors, or elite controllers (34). These individuals are treatment naive and remain clinically healthy for longer than 10 years. Although the underlying mechanisms resulting in control of HIV-1 infection are not yet fully understood, LTNPs exhibit enhanced HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation and killing of HIV-infected target cells compared to chronically infected patients (35, 36), and these cells in both peripheral blood and rectal mucosa of LTNPs are more likely to be polyfunctional (secrete multiple cytokines) (4, 14). A recent study has also demonstrated increased immune activation among a population of elite controllers (HIV RNA at <75 copies/μl in the absence of ART) compared to uninfected controls (23). Rectal mucosal CD4+ T cell levels appear to be preserved in HIV-infected elite controllers (14), while LPS levels remain elevated compared to those in HIV-uninfected controls (23), but the frequency of Th17 and Th1 T cells in the gut mucosa of these patients has not yet been studied.

The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate the interaction between gut mucosal T lymphocytes, Th17 cells, T cell cycling (as determined by Ki67+ expression), and the translocation of microbial products in LTNPs compared to findings from HIV-infected patients treated with prolonged (>5 years) ART. In addition, we quantified the number of peripheral CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of integrin-β7, a surrogate measure of α4β7 (47), which is a gut homing marker that acts as a coreceptor for HIV (1). Our findings show that LTNPs overall have intact CD4+ T cell populations in the gut mucosa, which is also reflected in the frequency of α4β7+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood. In addition, LTNPs have IL-17 expression in gut CD4+ T cells similar to that of HIV-uninfected controls. Finally, plasma LPS and sCD14 levels do not differ between LTNPs and controls and do not correlate with CD4+ IL-17+ T cells in either peripheral blood or colon. These findings support an association between lack of HIV disease progression and preservation of gut Th17 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Peripheral blood (PB) samples and colonic biopsy specimens were collected from 18 HIV-uninfected volunteers (HIV−), 22 HIV-infected patients treated with prolonged ART with plasma HIV RNA less than 50 copies/ml (VL [viral load]<50 group), and 14 LTNPs. All LTNPs had stable, nondeclining CD4+ T cell counts and HIV RNA of <50 copies/ml for at least 10 years in the absence of therapy. In addition, plasma samples were obtained from a total of 9 HIV−, 39 VL<50, and 68 LTNP individuals, including the majority of the patients who had undergone biopsy, for sCD14 analysis. Informed consent to undergo colonoscopy or give plasma samples for research purposes was obtained from all patients under an institutional review board (IRB)-approved NIH protocol. The participants were clinically asymptomatic at the time of the procedure. Viral loads were determined by ultrasensitive branched DNA (bDNA) assay (Versant HIV-1 software program, version 3.0; Siemens Corp., New York, NY).

Biopsy specimen collection and processing.

Study participants underwent an endoscopic procedure under moderate sedation as previously described (10). Briefly, between 16 to 20 biopsy specimens were randomly extracted from the rectosigmoid colon and digested using 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2,000 U DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min or 250 U benzonase (Novagen, Madison, WI) for 40 min at 37°C before being filtered through a 40-μm screen. Samples contained a mixture of inductive lymphoid tissue (isolated lymphoid follicles) as well as lamina propria lymphocytes as confirmed by histopathology (data not shown).

Immunophenotyping.

Immunophenotypic analysis was performed on blood, cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) for β7 and CCR5 staining only, and cells extracted from the gut biopsy specimens as described elsewhere (10, 46). In addition to a Live/Dead fixable blue dead cell stain (Invitrogen), the following antibodies were used: anti-CD3 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or anti-CD3 allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7 (clone SK7), anti-CD4 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), APC (clone SK3) or Qdot 605 (clone S3.5), anti-CD8 PerCP (clone SK1), anti-Ki67 phycoerythrin (PE) (clone B56), anti-CD27 FITC (clone M-T271), anti-CCR5 PE (clone 2D7) (BD Pharmingen), anti-CD45RO APC (clone UCHL1), anti-CD38 APC (clone HB7), anti-HLA-DR PE (clone L243), anti-CD25 APC (clone 2A3) (BD Biosciences), anti-FoxP3 PE (clone PCH101) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-β7 integrin PE-Cy5 (clone FIB504), anti-CCR5 PE (clone 2D7), and anti-CD27 FITC (clone M-T271) (BD Pharmingen). Due to cell number limitations, FoxP3 staining was not done for most participants. However, costaining with CD25 and FoxP3 was done in a small subset of samples and demonstrated that the majority of CD25high cells expressed FoxP3 (data not shown), which is in agreement with findings in other studies (30). Samples were acquired using a FACSCalibur or LSRII flow cytometer (BD Pharmingen). The data were analyzed using the FlowJo software program, version 8 (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Quantification of cytokine expression.

Cryopreserved PBMC and cells extracted from the gut biopsy specimens were rested overnight at 37°C before stimulation for 6 h with 40 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 1 μM ionomycin in the presence of 1 μl/ml of brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to prevent cytokine release. After two washes with RPMI medium containing 10% heat-inactivated human serum, cells were fixed and permeabilized according to the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm protocol. The cells were stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD3 PE-Cy7 or PerCP, anti-CD4 APC-Cy7, anti-CD8 PerCP, anti-CD27 FITC, anti-CD45RO PE-Cy7, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) APC (BD Biosciences), IL-17 PE, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) PacBlue (eBioscience). Samples were acquired and analyzed as described above. Th1 cells were defined as CD4+ IFN-γ+ and Th17 cells as CD4+ IL-17+ cells. For the analysis of the cryopreserved PBMC, cytokine expression was measured on memory cells by excluding the naive subset (CD27− CD45RO−). This exclusion was not done for the biopsy extracted cells, because the vast majority of T cells in the gut expressed a memory phenotype (reference 25 and personal observations).

Calculation of absolute numbers of gut T cell subsets.

Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets per gram of gut tissue were calculated as previously described (10). Briefly, the total cell count per gram of tissue was calculated by dividing the viable cell count by the tissue weight. This number was then multiplied by percentages obtained from flow cytometric analysis to determine the absolute cell count of the T cell subsets.

Measurement of soluble biomarkers.

Plasma samples were analyzed by a limulus amebocyte assay for LPS levels (Lonza Group, Switzerland) and by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for soluble CD14 (sCD14) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota). All listed tests were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Statistical analyses.

Values are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were used for between- and within-group comparisons, respectively. Spearman's rank tests were used to evaluate associations. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, all P values of ≤0.05 are shown; however, to account for multiple comparisons, only P values of <0.01 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the Prism v5.0 software program (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics.

The clinical characteristics of the three groups are summarized in Table 1. All treated participants initiated therapy during chronic infection, had been on ART for a median of 7 years (IQR, 5 to 8 years), and were virologically suppressed (<50 HIV RNA copies/ml) for at least 2 years at the time of biopsy. LTNP participants had blood and colonic HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/ml with stable CD4+ T cell counts and no history of AIDS-defining illnesses in the absence of ART.

Table 1.

Participant characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Value for groupd |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV− | VL<50 | LTNPs | |

| Age (yr) | 43 (37–50) | 46 (41–50) | 52 (43–58) |

| No. of CD4+ T cells/μl | 789 (554–1,070) | 519 (404–590) | 874 (771–1047) |

| % CD4+ T cells | 45 (41–51) | 30 (21–37) | 44 (40–49) |

| No. of CD8+ T cells/μl | 399 (269–531) | 703 (517–1011) | 703 (562–845) |

| % CD8+ T cells | 22 (19–26) | 41 (33–54) | 35 (26–39) |

| CD4/CD8 cell ratio | 2.15 (1.50–2.36) | 0.79 (0.42–1.12) | 1.26 (1.07–1.61) |

| Plasma HIV RNA (copies/ml) | NAb | <50 | <50 |

| Colon tissue HIV RNAc (copies/mg) | NA | <50 | <50 |

| Nadir CD4+ T cells/μl | NA | 184 (35–241) | 720 (639–829) |

Median values with IQR in parentheses.

NA, not applicable.

Tissue HIV RNA was available for only 18 of the VL < 50 and 13 of the LTNP participants.

For HIV− group, n = 18; for VL<50 group, n = 22; for LNTPs, n = 14.

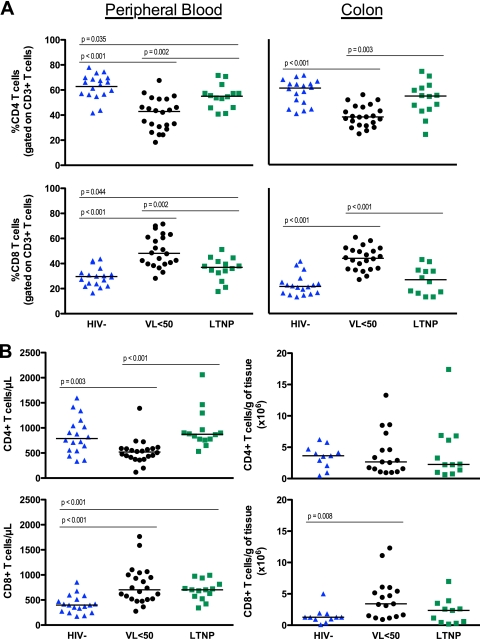

The proportions and absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the colonic mucosa were similar in LTNPs and controls.

In the colon, the proportion of CD4+ T cells was lower and the percentage of CD8+ T cells was significantly higher for VL<50 patients than for uninfected controls (percent CD4, 38.0 versus 61.1, P < 0.001; percent CD8, 44.1 versus 21.7, P < 0.001) and LTNPs (percent CD4, 38.0 versus 54.7, P = 0.003; percent CD8, 44.1 versus 27.0, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). This was consistent with the observations for peripheral blood. Although LTNPs had a lower proportion of CD4+ (55.1 versus 65.2, P = 0.035) and a higher proportion of CD8+ (48.2 versus 37.0, P = 0.044) T cells in PB than controls, there was no significant difference between the two groups for either population in the colon. Similarly, there was no difference in the absolute number of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells/g of gut tissue between LTNPs and HIV− controls (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The proportion (A) or absolute number (B) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and colon of HIV− (blue triangles), VL<50 (black circles), or LTNP (green squares) subjects. Mann-Whitney tests were used for statistical comparisons between groups.

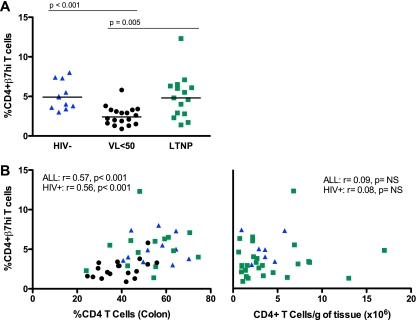

β7hi expression in peripheral blood did not differ between HIV− controls and LTNPs and correlated with the proportion of colon CD4+ T cells.

We measured the expression of β7 integrin and CCR5 on peripheral blood T lymphocytes. HIV− and LTNP individuals expressed similar levels of β7hi on CD4+ T cells in PB (4.9% versus 4.8%, P = 0.64) (Fig. 2A). Expression of β7hi was lower for the virally suppressed individuals than for HIV− controls (2.4% versus 4.9%, P < 0.001) and LTNPs (2.4% versus 4.8%, P = 0.005; Fig. 2A). Similar differences were observed with respect to CCR5 expression on PB CD4+ T cells, although there was no statistically significant difference observed between LTNPs and VL<50 individuals (7.2% versus 5.5%, P = 0.063; data not shown). In concordance with our previous findings (10), we observed higher β7hi expression on central memory (CD27+ CD45RO+) than on effector memory (CD27− CD45RO+) CD4+ T lymphocytes in the PB of all studied groups, while the reverse was true for CCR5 expression (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

To evaluate homing of T cells to the gut, the percentage of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of β7 was quantified by flow cytometry (A). Gating was performed as previously described (10). Between-group differences were evaluated by the Mann-Whitney test. Spearman's rank tests were used to assess correlations with the overall proportion (B, left panel) or absolute number (B, right panel) of CD4+ T cells in the gut mucosa. P values and r values are shown for comparisons including all three study groups and the two HIV+ groups. NS, not significant.

We next evaluated the relationship between β7hi and CCR5 expression on PB CD4+ T cells with both the proportion and absolute number of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the colon. Expression of β7hi but not CCR5 on PB T cells correlated with the proportion but not with the number of CD4+ T cells in the colon in a grouped analysis of all participants (percent CD4 cells, r = 0.57 and P < 0.001; no. of CD4+ T cells/g of tissue, r = 0.09 and P = 0.601) and when only the HIV+ groups were included (percent CD4 cells, r = 0.56 and P < 0.001; no. of CD4+ T cells/g of tissue, r = 0.08 and P = 0.679) (Fig. 2B). We evaluated these relationships further by grouping participants according to their relative proportion and number of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood. In participants with higher CD4+ T cell counts in PB (HIV− controls and LTNPs), there was no significant correlation between CD4+ T cells in the colon (absolute number or proportion) and β7hi expression in the PB.

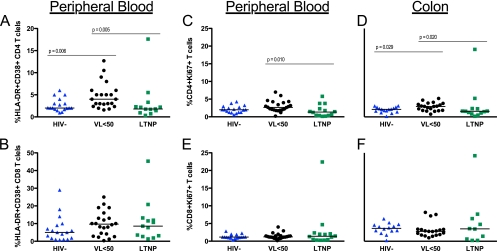

Cycling T cell populations in colon were similar in LTNPs and uninfected controls.

T cell activation in the peripheral blood was analyzed by quantifying HLA-DR and CD38 coexpression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CD4+ T cell activation was significantly higher for the VL<50 group than for HIV− controls (4.0% versus 2.0%, P = 0.006) and LTNPs (4% versus 1.8%, P = 0.005) (Fig. 3A) but was not different between the last 2 groups. Moreover, no significant differences in CD8+ T cell activation between groups were observed (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The proportion of CD4+ (A, C, and D) or CD8+ (B, E, and F) T cells with activated (HLA-DR+ CD38+) (A and B) or cycling (Ki67+) (C to F) phenotype was quantified by flow cytometry. Activation phenotype was determined only for PBMC. Mann-Whitney tests were used for between-group comparisons.

To further assess T cell activation and cycling in the gut, the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing Ki67+ was measured (Fig. 3C to F). In PB, the proportion of CD4+ Ki67+ T cells was higher for VL<50 patients than for LTNPs (2.7 versus 1.3, P = 0.010) but not for uninfected controls (2.7 versus 2.0, P = 0.061) (Fig. 3C). This subset was larger for the treated group than for both LTNPs (3.0 versus 1.6, P = 0.020) and controls (3.0 versus 2.1, P = 0.029) in the colon (Fig. 3D). At both sampling sites, the percentages of CD8+ Ki67+ T cells were similar among study groups (Fig. 3E and F). There were no significant differences in proportions of CD4+ Ki67+ or CD8+ Ki67+ T cells between the HIV− and LTNP groups. Cycling CD4+ T cells correlated with the percentage of CD4+ T cells in both PB (r = −0.37; P = 0.006) and colon (r = −0.29; P = 0.044) (data not shown).

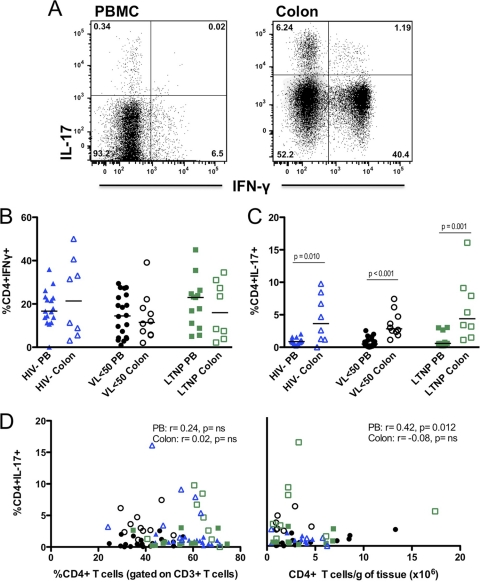

Proportions of Th17 cells did not differ between groups in either PB or colon and were not associated with size of CD4+ T cell population in colonic mucosa.

To further characterize the function of gut mucosal T lymphocytes, IFN-γ, IL-17, and TNF-α expression was measured in PB and colon CD4+ T cells after mitogenic stimulation. There were no significant differences in the percentages of CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells (Th1) either between groups or when PB and colon results were compared within each group (Fig. 4A). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of IL-17-expressing CD4+ T cells (Th17) was observed in the colon than in PB in all three groups (HIV−,3.64 versus 0.87%, P = 0.010; VL<50, 2.84 versus 0.50%, P < 0.001; LTNP, 4.39 v. 0.59%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Within each site, all groups had similar proportions of Th17 cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Using the gating strategy detailed for panel A, the proportion of Th1 (IFN-γ+) (B) or Th17 (IL-17+) (C) CD4+ T cells was quantified by flow cytometry after 6 h of stimulation with PMA-ionomycin. Experiments were performed using cryopreserved PBMC and freshly extracted gut tissue cells after overnight rest. Mann-Whitney tests were used for between-group comparisons, and P values < 0.05 are shown. Correlations between the percentage of PB and colon Th17 cells and both the overall proportion (D, left panel) and absolute number (D, right panel) of CD4+ T cells in the gut were evaluated using Spearman's rank tests. r values are shown.

Possible associations between IL-17 expression and CD4+ T cell population size were investigated to examine the role of Th17 cells in gut immunity in the absence of viremia. Neither the percentage nor the absolute number of CD4+ T cells in the colon correlated with the proportion of colonic Th17 cells (Fig. 4C). There was a weak association between Th17 cells in PB and the CD4+ T cell population size in the colon (r = 0.42; P = 0.012) (Fig. 4C).

In an expanded cohort, VL<50 patients but not LTNPs exhibited evidence of systemic monocyte activation.

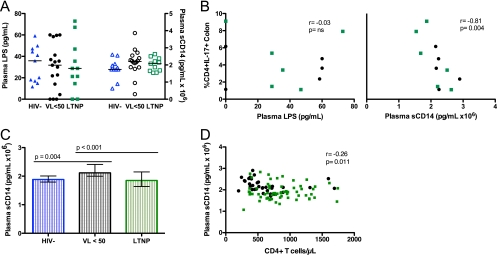

No significant difference was observed in plasma LPS and sCD14 levels among the three groups of biopsied individuals (Fig. 5A). However, there was a trend toward higher sCD14 levels for treated patients than for controls (P = 0.058). Among HIV+ cohorts, the percentage of Th17 cells in the colon inversely correlated with plasma sCD14 (r = −0.81; P = 0.004) but not with LPS levels (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Plasma levels of LPS and sCD14 were measured for participants who underwent biopsy (A) as well as an expanded cohort of patients who met the inclusion criteria for the three study groups (HIV−, VL<50, and LTNP) (C). P values < 0.05 are shown. Correlations between the proportion of Th17 cells in colon and both LPS and sCD14 in participants who underwent gut biopsy, as well as between peripheral CD4 T cell counts and sCD14 in the expanded cohort, were evaluated using Spearman's rank tests. r values are shown.

In order to further explore the degree of monocyte activation in LTNPs, we measured sCD14 levels in an expanded cohort of 116 patients, 68 of whom met the LTNP definition, 39 of whom were suppressed on therapy (VL<50), and 9 of whom were HIV uninfected (HIV−) (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 5C, VL<50 patients had significantly higher levels of sCD14 (106 pg/ml) than both LTNPs (2.12 versus 1.85, P < 0.001) and HIV− persons (2.12 versus 1.88, P = 0.004). HIV− controls and LTNPs had similar sCD14 levels (1.88 versus 1.85, P = 0.749). Plasma levels of sCD14 correlated weakly with peripheral CD4+ T cell counts/μl when all three (r = −0.22; P = 0.022) or just the HIV+ (r = −0.26; P = 0.011) expanded cohorts were analyzed (Fig. 5D).

Table 2.

Extended cohort participant characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Value for groupc |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV− | VL<50 | LTNPs | |

| Age (yr) | 36 (30–42) | 46 (41–50) | 48 (40–54) |

| No. of CD4+ T cells/μl | 908 (621–1,134) | 490 (399–698) | 802 (650–1,105) |

| % CD4+ T cells | 46 (39–49) | 29 (24–37) | 42 (36–48) |

| No. of CD8+ T cells/μl | 440 (319–501) | 760 (518–1,058) | 707 (499–972) |

| % CD8+ T cells | 24 (19–25) | 41 (34–53) | 36 (29–42) |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 2.01 (1.49–2.66) | 0.71 (0.50–1.10) | 1.17 (0.86–1.64) |

| Plasma HIV-RNA (copies/ml) | NAb | <50 | <50 |

| Nadir CD4+ T cells/μl | 908 (591–1,067) | 252 (148–413) | 658 (484–846) |

Median values with IQR in parenthesis.

NA, not applicable.

For HIV− group, n = 9; for VL<50 group, n = 39; for LTNPs, n = 68.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the frequency, phenotype, and functional status of T cell populations in the gut mucosa and peripheral blood of LTNPs, virologically suppressed HIV-1-infected patients on therapy, and HIV-uninfected controls, with a specific focus on the IL-17+ subset of CD4+ T cells. Overall, the size and phenotype of the CD4+ T cell population in the gut of LTNPs appeared intact and comparable to that of uninfected controls, as did markers of microbial translocation or monocyte activation.

Supporting previous observations (14, 21, 44), neither the proportions of colonic CD4+ T cells in the colon nor β7 expression on CD4+ T cells in PB differed between LTNPs and HIV− individuals. Expression of α4β7, a gut homing molecule, on CD4+ T cells may provide a selective advantage for HIV (1), and the cells expressing high levels of this marker are preferentially infected and depleted during acute SIV infection (24). It has also been demonstrated in SIV and HIV infection that β7 expression on PB CD4+ T cells may serve as a surrogate marker of CD4+ T cells in the colon (10, 47). The CD4+ T cell percentage in the gut and β7 expression in PB were both significantly lower for VL<50 patients than for the other two patient groups in our study, consistent with the decreased percentage (although not absolute number) of gut CD4+ T cells for these patients. Our observations support that LTNPs have normal circulating levels of α4β7hi CD4+ T cells. We also observed that the levels of CD4+ T cell cycling in the colon and activation in PB were strikingly similar between LTNPs and HIV− individuals and were lower for these two groups than for the VL<50 patients, supporting CD4 lymphopenia as the predominant driving force of CD4+ T cell activation and cycling in both sites. Furthermore, in concordance with previous data, cycling CD4+ T cells inversely correlated with CD4+ T cells in both the colon and PB, supporting the suggestion that CD4+ T cell homeostasis is similarly regulated in both compartments (10, 18). In contrast to previously published data, both treated and LTNP groups demonstrated normal levels of CD8+ T cell cycling (in PB and colon) and activation (in PB) (23). This could be due to our smaller sample size or the fact that we had a much lower proportion of chronic hepatitis C coinfection in our group (16%, compared to 79% in the other study). In addition, our study's definition of LTNPs included both stability of CD4+ T cell counts over time and HIV plasma viremia control criteria, whereas the aforementioned study examined a cohort of elite controllers defined only by viral control (23).

There is now ample evidence that the substantial depletion of colonic CD4+ T cells in early SIV and HIV infection may contribute to the extensive immune activation characteristic of progressive infection (40). Interestingly, however, in nonprogressive SIV infection, despite similar losses of mucosal CD4+ T cells, there exists neither the systemic depletion of CD4+ T cells nor the extensive immune activation characteristic of pathogenic SIV and HIV infection (19). Our study investigated these relationships in the nonprogressive human disease represented by LTNPs. Although we did not see any depletion of colonic CD4+ T cells in LTNPs (limited by our inability to study acute/early HIV infection of LTNPs), we did observe a lack of systemic monocyte activation in LTNPs compared to treated patients in a large cohort of patients. In this expanded cohort, we observed higher plasma levels of sCD14 in treated patients than both HIV− controls and LTNPs, as previously described (6). Additionally, it has been proposed that there is an association between LPS and both peripheral (6, 23, 31) and local (10) gut immune activation. However, we observed no correlation between sCD14 levels and peripheral activation or the size of the Th17 population in either the PB or colon. This could be due to the fact that the focus of our study was on HIV+ patients with suppressed viral replication (<50 copies/ml). While the shedding of sCD14 by monocytes occurs in response to stimulation by LPS and therefore the two measurements should be closely correlated, it is unclear if the threshold for monocyte activation by LPS differs at different stages of HIV infection. In addition, some data suggest that sCD14 may represent an acute-phase protein (3) and can be induced through monocyte activation directly by IL-6, which is elevated in HIV infection (38). Therefore, as suggested by other studies, there may be factors other than or in addition to LPS driving chronic immune activation (20, 43).

In our analysis, we observed greater proportions of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in the colon compared to the peripheral blood consistently across all study groups. LTNPs maintained normal proportions of Th17 cells both in the blood and colon, and the same appeared to be true for patients on long-term ART with HIV suppression, suggesting that prolonged ART can restore the Th17 subset (29), although other studies have showed that Th17 cells are not restored by ART in the periphery or colon, regardless of CD4+ T cell count or viral load (5, 12). Future studies could include quantification of CD161+ CD4 T cells, a population of gut-homing, Th17 lineage-committed T cells that has been shown to be depleted with Th17 cells in the PB of HIV-infected, treatment-naive individuals (41), to further clarify this issue. Additionally, LTNPs in our study had normal Treg/Th17 and Th1/Th17 ratios (data not shown); a loss of balance between these subsets is characteristic of untreated, pathogenic SIV infection and may predict disease progression (5, 9, 13, 24). This further indicates that, similar to the case with nonpathogenic SIV infection, HIV-infected LTNPs preserve balanced CD4+ T cell subsets in both blood and mucosal sites.

In conclusion, LTNPs have intact CD4+ T cell populations in the gut mucosa, including cycling and Th17 subsets, and do not show evidence of elevated monocyte activation. Future studies may further elucidate if these factors contribute to the control of HIV in the absence of therapy or are simply the result of the successful immune control of HIV in this unique cohort of HIV+ individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study participants for their generous donation of time and study samples, as well as the outpatient clinic 8 and GI suite staff at the NIH who managed their care.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arthos J., et al. 2008. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin α4β7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balagopal A., et al. 2008. Human immunodeficiency virus-related microbial translocation and progression of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 135:226–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bas S., Gauthier B. R., Spenato U., Stingelin S., Gabay C. 2004. CD14 is an acute-phase protein. J. Immunol. 172:4470–4479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Betts M. R., et al. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781–4789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brenchley J. M., et al. 2008. Differential Th17 CD4 T-cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic lentiviral infections. Blood 112:2826–2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brenchley J. M., et al. 2006. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 12:1365–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brenchley J. M., et al. 2004. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:749–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caradonna L., et al. 2000. Enteric bacteria, lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and clinical significance. J. Endotoxin Res. 6:205–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cecchinato V., et al. 2008. Altered balance between Th17 and Th1 cells at mucosal sites predicts AIDS progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 1:279–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ciccone E. J., et al. 2010. Cycling of gut mucosal CD4+ T cells decreases after prolonged anti-retroviral therapy and is associated with plasma LPS levels. Mucosal Immunol. 3:172–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connick E., et al. 2007. Substantial CD4+ T cell recovery and reconstitution of tissue architecture in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) in advanced HIV-1 infection following initiation of HAART, abstr. 28. Prog. Abstr. 14th Conf. Retroviruses Opportun. Infect., Los Angeles, CA, 25 to 28 February 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12. El Hed A., Khaitan A., Kozhaya L., Manel N., Daskalakis D., Borkowsky W., Valentine F., Littman D. R., Unutmaz D. 2010. Susceptibility of human Th17 cells to human immunodeficiency virus and their perturbation during infection. J. Infect. Dis. 201:843–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Favre D., et al. 2009. Critical loss of the balance between Th17 and T regulatory cell populations in pathogenic SIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferre A. L., et al. 2009. Mucosal immune responses to HIV-1 in elite controllers: a potential correlate of immune control. Blood 113:3978–3989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ford E. S., Puronen C. E., Sereti I. 2009. Immunopathogenesis of asymptomatic chronic HIV Infection: the calm before the storm. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 4:206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gautreaux M. D., Deitch E. A., Berg R. D. 1994. T lymphocytes in host defense against bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 62:2874–2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. George M. D., Reay E., Sankaran S., Dandekar S. 2005. Early antiretroviral therapy for simian immunodeficiency virus infection leads to mucosal CD4+ T-cell restoration and enhanced gene expression regulating mucosal repair and regeneration. J. Virol. 79:2709–2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gordon S. N., et al. 2010. Disruption of intestinal CD4+ T cell homeostasis is a key marker of systemic CD4+ T cell activation in HIV-infected individuals. J. Immunol. 185:5169–5179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordon S. N., et al. 2007. Severe depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells in AIDS-free simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J. Immunol. 179:3026–3034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gregson J. N., et al. 2009. Elevated plasma lipopolysaccharide is not sufficient to drive natural killer cell activation in HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS 23:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guadalupe M., et al. 2003. Severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 77:11708–11717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guadalupe M., et al. 2006. Viral suppression and immune restoration in the gastrointestinal mucosa of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients initiating therapy during primary or chronic infection. J. Virol. 80:8236–8247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hunt P. W., et al. 2008. Relationship between T cell activation and CD4+ T cell count in HIV-seropositive individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels in the absence of therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 197:126–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kader M., et al. 2009. Alpha4(+)beta7(hi)CD4(+) memory T cells harbor most Th-17 cells and are preferentially infected during acute SIV infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2:439–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lapenta C., et al. 1999. Human intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes are naturally permissive to HIV-1 infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1202–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee P. I., et al. 2009. Evidence for translocation of microbial products in patients with idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia. J. Infect. Dis. 199:1664–1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Q., et al. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434:1148–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lim S. G., et al. 1993. Loss of mucosal CD4 lymphocytes is an early feature of HIV infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 92:448–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macal M., et al. 2008. Effective CD4+ T-cell restoration in gut-associated lymphoid tissue of HIV-infected patients is associated with enhanced Th17 cells and polyfunctional HIV-specific T-cell responses. Mucosal Immunol. 1:475–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makita S., et al. 2004. CD4+CD25bright T cells in human intestinal lamina propria as regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 173:3119–3130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marchetti G., et al. 2008. Microbial translocation is associated with sustained failure in CD4+ T-cell reconstitution in HIV-infected patients on long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 22:2035–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mattapallil J. J., et al. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434:1093–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mehandru S., et al. 2004. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:761–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Migueles S. A., Connors M. 2010. Long-term nonprogressive disease among untreated HIV-infected individuals: clinical implications of understanding immune control of HIV. JAMA 304:194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Migueles S. A., et al. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat. Immunol. 3:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Migueles S. A., et al. 2008. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity 29:1009–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miossec P., Korn T., Kuchroo V. K. 2009. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:888–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neuhaus J., et al. 2010. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1788–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ouyang W., Kolls J. K., Zheng Y. 2008. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 28:454–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paiardini M., Frank I., Pandrea I., Apetrei C., Silvestri G. 2008. Mucosal immune dysfunction in AIDS pathogenesis. AIDS Rev. 10:36–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prendergast A., Prado J. G., Kang Y. H., Chen F., Riddell L. A., Luzzi G., Goulder P., Klenerman P. 2010. HIV-1 infection is characterized by profound depletion of CD161+ Th17 cells and gradual decline in regulatory T cells. AIDS 24:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raffatellu M., et al. 2008. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Med. 14:421–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rempel H., Sun B., Calosing C., Pillai S. K., Pulliam L. 2010. Interferon-alpha drives monocyte gene expression in chronic unsuppressed HIV-1 infection. AIDS 24:1415–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sankaran S., et al. 2005. Gut mucosal T cell responses and gene expression correlate with protection against disease in long-term HIV-1-infected nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9860–9865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schneider T., et al. 1995. Loss of CD4 T lymphocytes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the duodenal mucosa than in the peripheral blood. Berlin Diarrhea/Wasting Syndrome Study Group. Gut 37:524–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sereti I., et al. 2001. CD4 T cell expansions are associated with increased apoptosis rates of T lymphocytes during IL-2 cycles in HIV infected patients. AIDS 15:1765–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang X., et al. 2009. Monitoring alpha4beta7 integrin expression on circulating CD4+ T cells as a surrogate marker for tracking intestinal CD4+ T-cell loss in SIV infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2:518–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]