Abstract

Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) couples growth factor signaling to activation of the target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1). To study its role in mammals, we generated a Rheb knockout mouse. In contrast to mTOR or regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor) mutants, the inner cell mass of Rheb−/− embryos differentiated normally. Nevertheless, Rheb−/− embryos died around midgestation, most likely due to impaired development of the cardiovascular system. Rheb−/− embryonic fibroblasts showed decreased TORC1 activity, were smaller, and showed impaired proliferation. Rheb heterozygosity extended the life span of tuberous sclerosis complex 1-deficient (Tsc1−/−) embryos, indicating that there is a genetic interaction between the Tsc1 and Rheb genes in mouse.

INTRODUCTION

The Ras homolog enriched in brain gene (Rheb) is ubiquitously expressed in mammalian cells, with the highest expression levels found in brain and muscle (1). Rheb was initially identified as a gene whose expression is rapidly induced upon synaptic activity in the rat hippocampus (26). The Rheb gene encodes a small GTPase, closely related to Ras, that exists either in an active GTP-bound state or an inactive GDP-bound state (26). Although the molecular mechanism has not yet been clearly defined, Rheb-GTP activates the target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1). TORC1 consists of multiple protein components, including the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) itself and the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), and is a major regulator of cell growth that phosphorylates multiple downstream targets including p70 S6 kinase (S6K) and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding proteins 1 and 2 (4E-BP1 and 4E-BP2) (10). Rheb is inactivated by the tuberous sclerosis complex 1 and 2 (TSC1 and TSC2, respectively) GTPase activating protein (GAP) complex that catalyzes the conversion of Rheb-GTP to Rheb-GDP and thereby downregulates TORC1.

Although the function of Rheb has been extensively characterized in vitro (10), less is known about its function in vivo. Disruption of Drosophila Rheb (dRheb) arrested growth at the first larval stage, indicating an essential role for Rheb in development (16, 19, 20). However, Drosophila cells have only one Rheb gene while mammalian cells also express the closely related Rheb-like 1 (RhebL1) (16), which is also able to enhance TORC1 signaling in vitro, though in a less potent way (21).

In humans, inactivation of the TSC1-TSC2 complex leads to inappropriate activation of Rheb and results in the disease tuberous sclerosis (complex) (TSC) (3, 22, 23). Studies into the biology of the TSC1-TSC2 complex have significantly advanced our understanding of the mechanisms governing cell growth control, cognitive development, and TSC pathogenesis (10).

To gain further insights into the TSC1-TSC2-Rheb-TORC1 signaling axis, we inactivated the Rheb gene in mouse. We show that deletion of the Rheb gene in mouse leads to embryonic lethality during midgestation, most likely due to circulatory failure. Furthermore, Rheb−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were much smaller than control cells and were severely impaired in their ability to proliferate. Finally, we show that there is a genetic interaction between the Rheb and Tsc1 genes, resulting in a delay in the lethality of Tsc1−/− embryos.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Rheb mutant mice.

The Rheb targeting construct was generated as follows. The mouse Rheb genomic sequence (accession number ENSMUSG00000028945) was used to design primers for the targeting constructs. A PCR fragment (680 bp) containing exon 3 and flanking intronic sequence was amplified using the following primers: Forward (F), 5′-ATGCATGTGAATTATGGCCTGACTGCAG-3′; Reverse (R), 5′-GTCGACCATCACAGAATCTAACCAATCTG-3′.

The 5′ flanking intronic arm (4.4 kb) (F, 5′-GGTACCTTGAGGAGCACCCTGCTC-3′; R, 5′-CTCGAGACTGCTCTGTGGAGAACACTTCC-3′) and 3′ flanking intronic arm (3.3 kb) (F, 5′-GCGGCCGCCCTTTAACAGCTTAGCTGCCTTG-3′; R, 5′-CCGCGGCCTCACTCAAACATGCTATG-3′) were amplified using High Fidelity Taq Polymerase (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on embryonic stem (ES) cell genomic DNA and cloned in a vector containing a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK)-neomycin selection cassette and loxP sites, so that exon 3 was flanked by loxP sites and the selection cassette was placed in the 5′ intronic sequence. Exon 3 was sequenced to verify that no mutations were introduced during cloning. For counter-selection, a gene encoding diphtheria toxin chain A (DTA) was inserted at the 5′ end of the targeting construct. Recombination of the loxP sites will result in deletion of exon 3 and introduce a premature stop codon at codon 43. The targeting construct was linearized and electroporated into embryonic day 14 (E14) ES cells (derived from 129P2 mice). Cells were cultured in Buffalo rat liver (BRL) cell-conditioned medium in the presence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). After selection with G418 (200 μg/ml), targeted clones were identified by long-range PCR from the NEO gene to the region flanking the targeted sequence and transfected with a plasmid encoding Cre recombinase. A transfection was done with a plasmid containing cre. Clones with a normal karyotype were injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice to obtain chimeric mice. A male chimera was crossed with female C57BL/6N/HsD mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN), and the resulting offspring were back-crossed with C57BL/6 mice (at least nine crosses). Tsc1−/− mice (25) were maintained for at least nine crosses in C57BL/6N/HsD. All animal procedures were approved by the local ethics committee.

Immunohistochemistry and HE staining.

E11.5 embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Standard hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and immunostaining were performed on 6-μm slices. For the immunostaining a standard method with avidin biotin-immunoperoxidase-alkaline-phosphatase complex (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) was used in combination with primary antibodies against S6 phosphorylated at S235/S236 (pS6S235/236) (number 2211) and cleaved caspase-3 (number 9661) from Cell Signaling Technology (CST). A terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed on paraffin sections using an Apoptag peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit from Millipore (product number S7100; Billerica, MA). For the isolectin staining, 20-μm cryo-slices were prepared from E11.5 embryos. These sections were incubated overnight with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled isolectin from Invitrogen (catalogue number I21411; San Diego, CA).

Western blotting.

Whole embryos were isolated by dissection and homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2.5% SDS) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The concentration of the lysates was adjusted to 0.5 mg/ml, and 15 μg was used for Western blot analysis. The following antibodies were used: Rheb (number 4935), Akt phosphorylated at S473 (pAktS473) (number 4060), Akt (number 2920), pS6S235/236(number 2211), S6 (number 2217), 4E-BP1 phosphorylated at T37/T46 (p4E-BP1T37/46) (number 2855), and 4E-BP1 (number 9644) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danver, MA) and actin from Chemicon/Millipore (catalogue number MAB1501R; Billerica, MA). Bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and quantification was done using ImageJ64 software.

Cell culture and cell surface measurement.

E11.5 embryos were minced and incubated in trypsin-EDTA solution at 37°C for 5 to 15 min. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), was added to the cells, and the suspension was filtered. Several rounds of trypsinization were performed to obtain an optimal yield. The final cell suspension was then centrifuged (930 × g for 5 min), and the cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FCS and antibiotics prior to plating out.

To estimate the surface area of individual cells, phase-contrast images of cultured MEFs at ×5 magnification were analyzed using ImageJ64 software.

FACS analysis.

Cells were prepared for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis according to standard procedures. Briefly, ∼1 × 106 washed cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.01% (wt/vol) NaN3, 40 μg/ml RNase A, and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide, and ∼2 × 105 cells were run through a FACS Aria I flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cell cycle analysis was performed using a Dean-Jett-Fox model on FlowJo software (version 9.0.2).

QPCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from E11.5 embryos using Trizol according to a standard protocol (catalogue number 15596026; Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and reversed transcribed into DNA (RevertAid Premium First strand cDNA synthesis kit; catalogue number K1652; Fermentas Ammersbek, Germany). Quantitative PCR (QPCR) analysis was performed using real-time fluorescence determination in an iCycler iQ Detection System (Bio-Rad, Netherlands). Primers were designed using primer3 online software. Target gene expression levels were expressed relative to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT). The following primers were used: for HPRT, TCAGGAGAGAAAGATGTGATTG (F) and CAGCCAACACTGCTGAAACA (R); for vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), AATGCTTTCTCCGCTCTGAA (F) and CAGGCTGCTGTAACGATGAA (R).

RESULTS

Rheb is essential for murine development beyond E12.

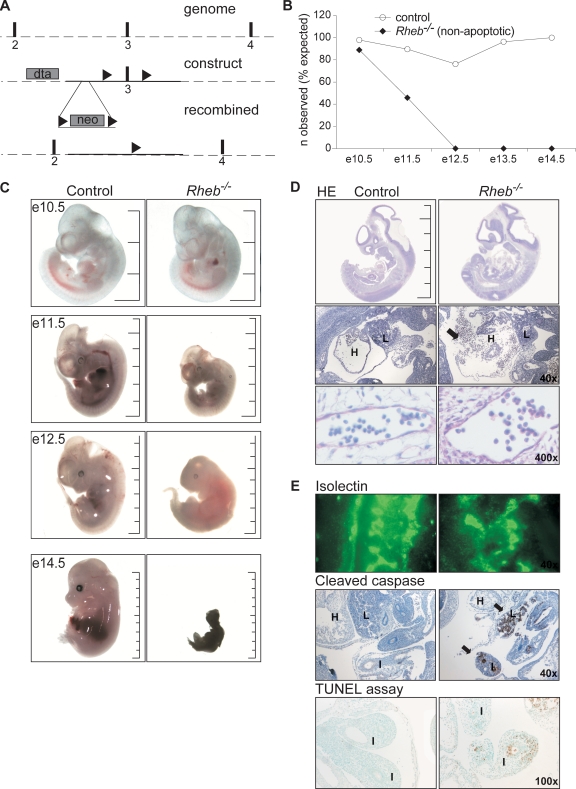

To investigate the role of Rheb in vivo, we generated a Rheb knockout mouse by inserting loxP sites in the intronic sequences flanking exon 3 of the Rheb gene through homologous recombination (Fig. 1A). Subsequent expression of Cre recombinase in the targeted embryonic stem (ES) cells resulted in deletion of exon 3 and germ line inactivation of the Rheb gene. Rheb+/− mice were born in Mendelian ratios from crosses of wild-type and heterozygous mice (Rheb+/+, 56; Rheb+/−, 44; χ2 = 1.44; P = 0.23; χ2 test), and adult Rheb+/− mice showed no differences in survival (measured from weaning until 8 months of age) or in general health, compared to wild-type mice.

Fig. 1.

Rheb−/− embryos die in midgestation and show impaired development of the circulatory system. (A) Strategy to generate a Rheb knockout mouse. At top, the wild-type Rheb locus shows exons 2 to 4 depicted as black boxes. The middle scheme shows the targeting construct used for the generation of Rheb−/− mice with the gene encoding the diphtheria toxin A chain (DTA) outside the homologous recombination sites, the neomycin resistance gene (NEO) inserted in introns 2 and 3, and the loxP sites in the intronic regions flanking exon 3. At bottom, the mutant Rheb locus is depicted after homologous recombination and the expression of Cre recombinase. (B) Embryonic survival curve of control and Rheb−/− embryos. Control embryos are either wild-type or Rheb+/− embryos as no differences could be detected between them. From E12.5 on, only apoptotic Rheb−/− embryos were observed. (C) Gross appearance of Rheb−/− embryos compared to controls. Embryos were sacrificed at the indicated time points. Control embryos are either wild type or Rheb+/− as no differences could be detected between them. The total scale bar corresponds to 1 cm. (D) Representative examples of hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining performed on E11.5 embryos. Scale bar, 1 cm. In the middle panel a ×40 magnification of the abdominal region is displayed; in the lower panel a ×400 magnification of a brain vessel is shown. Note the absence of a myocardial lining of the heart. Erythrocytes in the abdominal cavity of the Rheb−/− embryo are indicated (arrow). Staining was performed on three Rheb−/− and five control embryos. (E) Representative examples of immunostaining performed on E11.5 embryos using antibodies for isolectin, an endothelial marker and for the cleaved form of caspase-3, an apoptosis marker. In the lower panel representative images of a TUNEL assay, a detection method for DNA fragmentation, are displayed. The arrows indicate patches of apoptotic cells in the liver and intestinal lumen in the Rheb−/− embryo. Immunostaining was performed on three Rheb−/− and five control embryos. H, heart; L, liver; I, intestine.

Genotypes obtained from 7-day-old pups from heterozygous crosses revealed that none of the homozygous pups survived the neonatal period (Rheb+/+, 9; Rheb+/−, 17; χ2 = 8.69; P < 0.05; χ2 test for Mendelian distribution). To determine the timing of lethality of Rheb−/− embryos, embryos from E10.5 to E14.5 were analyzed. Homozygous mutants were observed in Mendelian ratios at E10.5 (Rheb+/+, 12; Rheb+/−, 21; Rheb−/−, 10; χ2 = 0.21; P = 0.90; χ2 test) and appeared relatively normal. At E11.5, nine empty decidua (13% of the total), five resorbed embryos (7% of total), and one Rheb−/− embryo with a clear apoptotic appearance (1.5% of total) were identified. However, Rheb−/− embryos were still found in Mendelian ratios (Rheb+/+, 12; Rheb+/−, 35; Rheb−/−, 9; χ2 = 3.82; P = 0.15; χ2 test). As shown in Fig. 1B, the viability of the homozygous mutants declined sharply around E12.5. All homozygous E12.5 embryos were clearly apoptotic, and from E13.5 on only resorbed homozygous embryos were observed.

Rheb is required for proper development of the cardiovascular system.

Although Rheb−/− E10.5 embryos tended to be smaller than controls, their gross morphology appeared normal (Fig. 1C). In contrast, Rheb−/− E12.5 embryos were clearly smaller than control embryos and invariably had an apoptotic appearance (size: Rheb+/+, 0.88 cm; Rheb+/−, 0.89 cm; Rheb−/−, 0.68 cm; K = 13.94; P < 0.05 by a Kruskal Wallis test; posthoc test: Rheb+/+ versus Rheb+/−, P > 0.05; Rheb+/+ versus Rheb−/−, P < 0.05; Rheb+/− versus Rheb−/−, P < 0.05, by a Dunn's multiple comparison test) (Fig. 1C). To investigate the cause of death of Rheb−/− embryos, we performed hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stainings of three E11.5 embryos (Fig. 1D). Although there was some variation between the E11.5 Rheb−/− embryos examined, they were all less well developed than those of control littermates. In particular, heart development was impaired. In two of three Rheb−/− embryos, pericardial hemorrhaging was observed (Fig. 1D) in combination with thinning of the ventricular walls, pointing toward cardiorrhexis. In the remaining embryo, pericardial hemorrhaging was not observed, but this embryo also showed notable thinning of the ventricular walls. No obvious defects were observed in the vasculature of Rheb−/− embryos, as assessed by high-magnification HE images and isolectin staining (Fig. 1D and E).

A failure in heart development may lead to circulatory failure and hypoxia in different organs. To determine the causes of cell death in the Rheb−/− embryos in more detail, we examined caspase and DNA fragmentation as markers of apoptosis (Fig. 1E). Cleaved caspase was detected in groups of cells throughout the Rheb−/− embryos, particularly in the liver (Fig. 1E), and patches of apoptotic cells containing fragmented DNA were detected in different organs of the Rheb−/− embryos using a TUNEL assay (Fig. 1E). Control Rheb+/+ and Rheb+/− embryos did not show such patches of apoptotic cells using either the TUNEL assay or cleaved caspase as a marker. In line with this, cells with fragmented nuclei could be observed in different organ systems.

In addition to areas of apoptotic cells, swollen cells containing vacuoles could be identified in the Rheb−/− embryos, indicating necrosis (data not shown).

Taken together, these results suggest that Rheb−/− embryos probably die due to circulatory failure, secondary to a poorly developed heart. Notably, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− embryos die around the same embryonic day with similar pathological features, indicating that both activation and inhibition of growth factor signaling to TORC1 result in comparable phenotypes (11, 15, 25).

Rheb deletion impairs TORC1 activity.

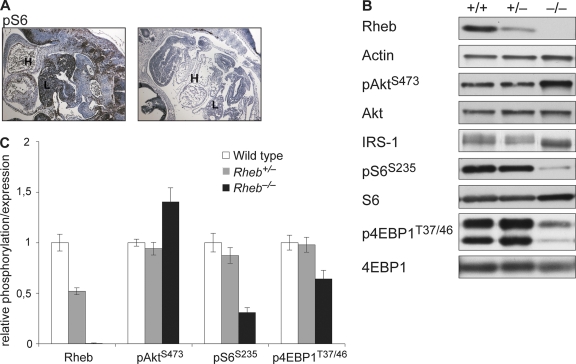

Rheb is a robust activator of the TORC1 complex in vitro and in Drosophila. To test whether this was also the case in mice, we stained E11.5 embryos for S235/236-phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (pS6), a readout for TORC1 activation (17). As shown in Fig. 2A, S6 S235/236 phosphorylation was virtually absent in Rheb−/− embryos. To quantify the effect of Rheb deletion on TORC1 activity, we measured S6 S235/236 and 4E-BP1 T37/46 phosphorylation in E11.5 embryonal lysates. Phosphorylation of S6 at positions S235/236 was significantly reduced in Rheb−/− E11.5 embryos compared to wild-type littermates, comparable to the decrease found in hepatocytes of S6K1−/− S6K2−/− mice (17) (pS6: 31% of control; F2,32 = 22.0 and P < 0.0001; Tukey's multiple comparison test for Rheb+/+ versus Rheb−/−, q = 8.45 and P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 at positions T37/46 was decreased (p4E-BP1, 64% of control; F2,32 = 6.27 and P < 0.01; for Rheb+/+ versus Rheb−/−, q = 4.64 and P < 0.05). Taken together, these results show that the TORC1 pathway is less active in Rheb−/− embryos. In contrast, no differences could be detected between heterozygous and wild-type tissues, indicating that Rheb levels have to be decreased by more than 50% to significantly affect TORC1 activity (for pS6, Rheb+/+ versus Rheb+/−, q = 1.66 and P > 0.05; and for p4E-BP1, Rheb+/+ versus Rheb+/−, q = 0.28 and P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Akt-TORC1 signaling is affected in Rheb−/− embryos. (A) Representative examples of an immunostaining performed on E11.5 embryos using an antibody for S235/236-phosphorylated ribosomal S6 (pS6 at Ser235/236), a readout for TORC1 activation. Note the decreased staining for S235/236-phosphorylated S6 in the Rheb−/− embryo. Immunostaining was performed on three Rheb−/− and five control embryos. H, heart; L, liver. (B) Representative immunoblots of Rheb expression, Akt S473 phosphorylation, IRS-1 mobility, S6 S235/236 phosphorylation, and 4E-BP1 T37/40 phosphorylation in lysates prepared from whole E11.5 Rheb−/− and control embryos. Note that the increased mobility of IRS-1 corresponds to decreased phosphorylation of this protein. (C) Quantification of immunoblotting results. Wild type, n = 4; Rheb+/−, n = 6; Rheb−/−, n = 4. All these samples were run in at least two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

In vitro, the TORC1 pathway is subject to negative feedback. For example, Tsc2−/− cells are less responsive to insulin while cells pretreated with rapamycin show increased Akt activation upon insulin stimulation (9). The negative feedback loops in the pathway are directed toward different upstream components, including the insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, and converge on Akt (9). To test whether this feedback loop operates in vivo, we estimated IRS-1 and Akt S473 phosphorylation levels in Rheb−/− E11.5 embryos. Consistent with the existence of a negative feedback loop, IRS-1 mobility and Akt S473 phosphorylation were increased in Rheb−/− embryos compared to wild-type and Rheb+/− littermates (F2,39 = 8.01 and P < 0.01; Rheb+/+ versus Rheb+/−, q = 0.62 and P > 0.05; Rheb+/+ versus Rheb−/−, q = 4.35 and P < 0.05; Rheb+/− versus Rheb−/−, q = 5.36 and P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B) (8).

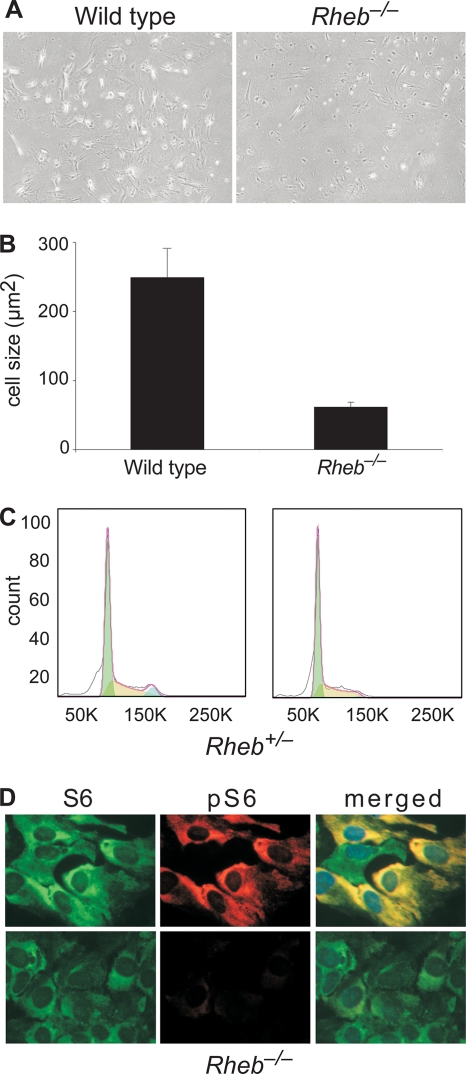

Rheb is required for cell growth and proliferation.

In Drosophila deletion of dRheb affects both cell size and the cell cycle (16, 19, 20). To investigate whether deletion of Rheb has similar effects in murine cells, we cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from E11.5 Rheb−/− and control embryos. MEFs isolated from Rheb+/+ and Rheb+/− embryos grew with the same characteristics (data not shown), but although it was possible to obtain Rheb−/− cells, they hardly proliferated (Fig. 3A). Notably, the surface area of Rheb−/− cells was significantly reduced compared to that of control cells (Rheb+/+, 240 μm2; Rheb−/−, 61.4 μm2; F1,108 = 28 and P < 0.01, by analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (Fig. 3B). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis indicated that fewer Rheb−/− MEFs than control MEFs entered G2, and a higher percentage of Rheb−/− cells was found in G1 (in G2, Rheb+/+, 5.79%; Rheb−/−, 1.29%; in G1, Rheb+/+, 50.0%; Rheb−/−, 54.5%) (Fig. 3C). In addition, TORC1 signaling was severely decreased, as assessed by the S235/236 phosphorylation status of S6 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Rheb−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) are small and do not proliferate. (A) Representative phase-contrast pictures of wild-type and Rheb−/− MEFs. (B) Rheb−/− MEFs are reduced in size (P < 0.01). Cell areas of 45 wild-type and 65 Rheb−/− MEFs were measured. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. (C) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of control and Rheb−/− MEFs. Populations of cells in different phases were estimated using the Dean-Jett-Fox model (FlowJo software, version 9.0.2). (D) Immunostaining of Rheb+/− and Rheb−/− MEFs with antibodies for S6 and S235/236-phosphorylated S6 (pS6). Although most of the Rheb+/− cells stain positive for phosphorylated S6, virtually none of the Rheb−/− MEFs show S6 phosphorylation.

Rheb heterozygosity extends Tsc1−/− embryo life span.

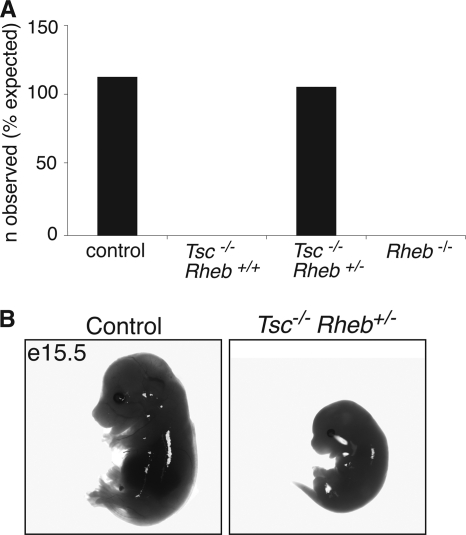

In Drosophila, heterozygosity for dRheb partially rescued the lethality of dTsc1−/− flies (20, 27). To investigate whether a similar genetic interaction could be observed in mice, we set up Tsc1+/− Rheb+/− intercrosses (Tsc1+/− Rheb+/− × Tsc1+/− Rheb+/−). Tsc1−/− embryos were reported to die between E10.5 and E13.5 (25). Indeed, at E11.5 we found only severely apoptotic Tsc1−/− Rheb+/+ embryos (data not shown). If there was a full rescue of the Tsc1−/− embryonic lethality, Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− pups would be expected to be born with a frequency of one out of eight. However, of the 43 pups analyzed, none had this genotype (significantly different from the expected ratio; P < 0.01).

Therefore, embryos from the same intercrosses were analyzed at E15.5 to detect a possible partial rescue of the lethality. Although these intercrosses should result in nine different genotypes, Rheb−/− embryos were not observed with any combination of Tsc1 alleles, indicating that Rheb forms an essential link to TORC1 signaling. In addition, Tsc1−/− embryos with Rheb+/+ or Rheb−/− alleles were not found (Fig. 4A). However, Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− embryos were identified at Mendelian ratios (37 decidua; 5 Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− embryos observed; 4.63 expected) (Fig. 4A), although they were smaller, developmentally retarded, and apoptotic compared to the control embryos (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results indicate that there is a genetic interaction between the Tsc1 and Rheb genes in mice and that Rheb heterozygosity extends the life span of Tsc1−/− embryos by approximately 4 days.

Fig. 4.

Rheb heterozygosity partially rescues the lethality of Tsc1−/− embryos. (A) Survival beyond E15.5 of different genotypes resulting from Tsc1+/− Rheb+/− intercrosses. Control embryos are embryos with all possible combinations of wild-type and heterozygous alleles. Rheb−/− embryos may have a wild-type, heterozygous, or homozygous genotype for Tsc1; however, none of these combinations was observed. Note that Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− embryos were observed in Mendelian ratios. (B) Example of a control (Tsc+/+ Rheb+/−) and a Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− embryo at E15.5. The Tsc1−/− Rheb+/− embryo is clearly smaller and developmentally retarded compared to the control embryo. In addition, it is already apoptotic, suggestive of resorption within 1 day.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that Rheb, a vital component of TORC1 signaling, is essential for murine development beyond E12. Interestingly, mTor−/− and raptor−/− embryos, which lack core TORC1 components, die before E8.5, significantly earlier than Rheb−/− embryos (6, 7, 14). Therefore, our results indicate that Rheb is not necessary for full TORC1 activation during early embryonic development. Possibly, RhebL1 partially compensates for the loss of Rheb. Alternatively, TORC1 exhibits Rheb-independent activity in vivo.

Rheb has been shown to activate growth in adult cardiomyocytes (24), and increased TORC1 activity in the adult heart is involved in cardiac hypertrophy (18). In line with these observations, the midgestational lethality of Rheb−/− embryos is most likely due to impaired heart development, implying that TORC1 signaling is critical for heart physiology during embryonal development. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), an essential factor for embryonic cardiogenesis and angiogenesis, is under the control of TORC1 via hypoxia inducible transcription factor 1 (HIF-1) (2, 4, 28). Although it is possible that the defects in cardiovascular development in the Rheb−/− embryos are due to decreased VEGFA expression, equal expression levels of VEGFA were found in Rheb−/−, Rheb+/−, and Rheb+/+ embryos (QPCR analysis) (data not shown), making it unlikely that decreased VEGFA levels are the key to the cardiovascular impairments in the Rheb−/− embryos. Next to VEGFA, other factors like angiopoietin and ephrins are critical for cardiovascular development, and dysregulation of these might possibly underlie the lethality of the Rheb−/− embryos (5).

Our studies of Rheb−/− MEFs indicate that Rheb is essential for cell growth and cell cycle progression. Consistent with these data, increased Rheb levels induce cell cycle progression in Drosophila (19). In contrast to Rheb−/− MEFs, cell proliferation in S6K1−/−/S6K2−/− MEFs is not impaired, probably because TORC1 signaling toward other targets is still intact (17).

Finally, we show that Rheb heterozygosity extends the life span of Tsc1−/− embryos. However, as in Drosophila, decreasing Rheb levels do not lead to a total rescue from Tsc1−/− lethality (20, 27). This implies that Rheb may not be the only target of the TSC1-TSC2 complex during murine embryonic development. Possibly, the interaction of hamartin with ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) proteins, regulating cell adhesion, is important for proper embryonic development (12). Alternatively, aberrant β-catenin signaling, as implicated in TSC, may play a role in the embryonic lethality of Tsc1−/− embryos (13).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reinier van der Linden for help with the FACS analysis, Edwin Mientjes for help with culturing of MEFs, Minetta Elgersma and Mehrnoush A. Jolfaei for managing the mouse colony and genotyping, and Yanto Ridwan for help with the TUNEL assay. Fried Zwartkruis, Marcel Vermeij, and Esther de Graaff are thanked for valuable advice.

This work was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (ZoNMW-VICI grant to Y.E. and TopTalent grant to S.M.I.G).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aspuria P. J., Tamanoi F. 2004. The Rheb family of GTP-binding proteins. Cell Signal. 16:1105–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carmeliet P., et al. 1996. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380:435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium 1993. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 75:1305–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrara N., et al. 1996. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380:439–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gale N. W., Yancopoulos G. D. 1999. Growth factors acting via endothelial cell-specific receptor tyrosine kinases: VEGFs, angiopoietins, and ephrins in vascular development. Genes Dev. 13:1055–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gangloff Y. G., et al. 2004. Disruption of the mouse mTOR gene leads to early postimplantation lethality and prohibits embryonic stem cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:9508–9516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guertin D. A., et al. 2006. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCα, but not S6K1. Dev. Cell 11:859–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrington L. S., et al. 2004. The TSC1-2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J. Cell Biol. 166:213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrington L. S., Findlay G. M., Lamb R. F. 2005. Restraining PI3K: mTOR signalling goes back to the membrane. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30:35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang J., Manning B. D. 2009. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37:217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwiatkowski D. J., et al. 2002. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lamb R. F., et al. 2000. The TSC1 tumour suppressor hamartin regulates cell adhesion through ERM proteins and the GTPase Rho. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mak B. C., Kenerson H. L., Aicher L. D., Barnes E. A., Yeung R. S. 2005. Aberrant beta-catenin signaling in tuberous sclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 167:107–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murakami M., et al. 2004. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6710–6718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Onda H., Lueck A., Marks P. W., Warren H. B., Kwiatkowski D. J. 1999. Tsc2+/− mice develop tumors in multiple sites that express gelsolin and are influenced by genetic background. J. Clin. Invest. 104:687–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patel P. H., et al. 2003. Drosophila Rheb GTPase is required for cell cycle progression and cell growth. J. Cell Sci. 116:3601–3610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pende M., et al. 2004. S6K1−/−/S6K2−/− mice exhibit perinatal lethality and rapamycin-sensitive 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation and reveal a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent S6 kinase pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:3112–3124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Proud C. G. 2004. Ras, PI3-kinase and mTOR signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 63:403–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saucedo L. J., et al. 2003. Rheb promotes cell growth as a component of the insulin/TOR signalling network. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:566–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stocker H., et al. 2003. Rheb is an essential regulator of S6K in controlling cell growth in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tee A. R., Blenis J., Proud C. G. 2005. Analysis of mTOR signaling by the small G-proteins, Rheb and RhebL1. FEBS Lett. 579:4763–4768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tee A. R., Manning B. D., Roux P. P., Cantley L. C., Blenis J. 2003. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr. Biol. 13:1259–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Slegtenhorst M., et al. 1997. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 277:805–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Y., et al. 2008. Rheb activates protein synthesis and growth in adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 45:812–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilson C., et al. 2005. A mouse model of tuberous sclerosis 1 showing background specific early post-natal mortality and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:1839–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamagata K., et al. 1994. rheb, a growth factor- and synaptic activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel Ras-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 269:16333–16339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y., et al. 2003. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:578–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhong H., et al. 2000. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells: implications for tumor angiogenesis and therapeutics. Cancer Res. 60:1541–1545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]