Abstract

How a cell chooses between nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) to repair a double-strand break (DSB) is a central and largely unanswered question. Although there is evidence of competition between HR and NHEJ, because of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK)'s cellular abundance, it seems that there must be more to the repair pathway choice than direct competition. Both a mutational approach and chemical inhibition were utilized to address how DNA-PK affects HR. We find that DNA-PK's ability to repress HR is both titratable and entirely dependent on its enzymatic activity. Still, although requisite, robust enzymatic activity is not sufficient to inhibit HR. Emerging data (including the data presented here) document the functional complexities of DNA-PK's extensive phosphorylations that likely occur on more than 40 sites. Even more, we show here that certain phosphorylations of the DNA-PK large catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) clearly promote HR while inhibiting NHEJ, and we conclude that the phosphorylation status of DNA-PK impacts how a cell chooses to repair a DSB.

Introduction

Although DNA is the genetic blueprint for all living organisms, it is very sensitive to various forms of damage, including oxidation, hydrolysis, and methylation. One of the most cytotoxic forms of DNA damage is the DNA double-strand break (DSB). Two major DNA repair pathways (nonhomologous end joining [NHEJ] and homologous recombination [HR]) repair DSBs in all eukaryotes. NHEJ (the primary pathway in higher eukaryotes) is active throughout the cell cycle (33), whereas HR is generally limited to S and G2 when a sister chromatid is available as a repair template. In addition to classical NHEJ (c-NHEJ) and HR, we and others have described fairly robust alternative DNA end-joining (a-NHEJ) repair pathways that also contribute to double-strand break repair (DSBR), although their roles are less well understood (8, 9, 40).

The DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) is central in NHEJ (reviewed in references 25 and 28). DNA-PK is comprised of two subunits, as follows: the DNA end binding heterodimer Ku initially binds DNA ends and recruits the DNA-PK large catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). Two DNA-PK complexes target the two DNA ends at a single DSB; synapsis of the two complexes provides the structural platform for repair. After initial binding and synapsis, DNA-PK recruits other factors (XRCC4/ligase IV/XLF, DNA polymerases μ and λ, and the Artemis nuclease) to the site of damage. It has been shown that DNA-PK's kinase activity is requisite to its role in NHEJ (22). We and others have reported that although most NHEJ factors are excellent in vitro and in vivo targets of DNA-PK enzymatic activity, DNA-PKcs itself is the only NHEJ factor that has been shown (to date) to be a functionally relevant target (for NHEJ) of its own enzymatic activity (5, 10, 14, 15, 19, 41, 42). Moreover, phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs occurs on many sites (probably more than 40) and is functionally complex (13, 28). Distinct phosphorylation events have distinct functional consequences. Two major clusters of autophosphorylation sites reciprocally regulate DNA end processing during NHEJ. Phosphorylation of a site within the putative activation (or T) loop of the kinase domain inactivates the enzyme but does not induce kinase dissociation (14). Additional (as-yet-undefined) DNA-PK-mediated phosphorylation events are required to facilitate later steps of end joining (14).

It is well appreciated that cells with defects in NHEJ (because of inactivating mutations in Ku, DNA-PKcs, or the XRCC4/ligase IV complex) are more proficient in their utilization of the HR pathway, and it has been suggested that the two pathways are in direct competition. However, because of DNA-PK cellular abundance, it seems likely that there must be more to the repair pathway choice than competition between HR and NHEJ. Simply put, if the two pathways are in “head-to-head” competition, DNA-PK will always win, a fact likely exacerbated by the relatively high association and low dissociation rates of both Ku for DNA ends and DNA-PKcs for Ku/DNA complexes (38). The imbalance in this competition is particularly relevant in human cells, which express ∼50 times more DNA-PK than rodent cells. Therefore, it seems likely that in cells that express abundant DNA-PK, some mechanism(s) must actively promote HR or inhibit NHEJ.

Here we show that inhibition of HR by DNA-PK is titratable. Moreover, inhibition of HR by DNA-PK is absolutely dependent on its enzymatic activity and is markedly modulated by phosphorylation. Several newly defined phosphorylation sites studied here impact NHEJ negatively while promoting HR; phosphorylation of these sites would provide a mechanism to limit NHEJ while promoting HR, perhaps facilitating accurate repair of certain types of damage. In most (but not all) cases, DNA-PKcs mutants that are proficient in NHEJ efficiently inhibit HR, while those that have a reduced ability to facilitate NHEJ allow increased HR, suggesting that failed NHEJ results in increased HR. Thus, in most cases, proficient NHEJ inhibits HR, while failed NHEJ results in increased HR. In contrast, analyses of one mutant that cannot sustain NHEJ but still inhibits HR suggest that a DNA-PK-mediated phosphorylation event is required for the enzyme's ability to impede HR. However, further mutational analyses demonstrate that phosphorylation of any of the many sites defined to date within DNA-PKcs, Ku86, or XRCC4 cannot account for the requirement of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity to impede HR. Similarly, coexpression studies suggest that defined DNA-PK phosphorylation sites within Ku70, Artemis, 53BP1, and RPA32 also do not account for the requirement of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity to impede HR. We conclude that additional DNA-PK phosphorylation(s) (either of itself or other downstream targets) is required for DNA-PK inhibition of HR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, expression plasmids, and transfectants.

Methods to derive the V3, xrs6, and XR-1 transfectants have been described previously (10, 12, 42). Briefly, cells were cultured in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin-streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin (complete medium) and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The DNA-PKcs (wild-type and mutant) expression plasmids utilized in this study are listed in Table 1 and were described previously (10, 12, 14, 22, 36). Wild-type and mutant XRCC4, Ku70, and Ku86 expression plasmids were described previously (15, 42). Wild-type and mutant 53BP1 constructs were generous gifts from Junjie Chen (MD Anderson, Houston, TX) and were described previously (30). Wild-type RPA32 expression constructs have been described previously (21). Similar expression constructs in which phosphorylation sites in RPA32 are mutated to either alanine or aspartic acid phosphorylation (4) were used to examine the role of RPA phosphorylation in the regulation of HR by DNA-PK. The construction of these plasmids will be described elsewhere. The I-SceI expression plasmid utilized in this study includes the I-SceI coding sequence in pcDNA6 and confers blasticidin resistance as described previously (9).

Table 1.

Summary of DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation and catalytic mutants

| DNA-PKcs construct | Substitution site(s) | Level of: |

Description (reference) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioresistance | Kinase activity | |||

| Wild type | Full-length human DNA-PKcs | +++++ | +++++ | (36) |

| Vector | pCMV6 | − | − | (36) |

| ABCDE>Ala | T2609A, S2612A, T2620A, S2624A, T2638A, T2647A | − − −a | +++++ | Limited end processing; substantially more radiosensitive than V3 parental strain (12) |

| ABCDE>Asp | T2609D, S2612D, T2620D, S2624D, T2638D, T2647D | ± | +++++ | Normal end processing (12) |

| PQR>Ala | S2023A, S2029A, S2041A, S2053A, S2056A | +++ | +++++ | Excessive end processing (10) |

| PQR>Asp | S2023D, S2029D, S2041D, S2053D, S2056D | +++++ | +++++ | Limited end processing; poorly expressed (10) |

| M>Ala | S3205A | +++++ | +++++ | ATM site in vivo; Fig. 4 (16) |

| M>Asp | S3205D | +++++ | +++++ | ATM site in vivo; Fig. 4 (16) |

| T>Ala | T3950A | +++ | +++++ | Putative T-loop site (14) |

| T>Asp | T3950D | − | − | Putative T-loop site (14) |

| JK>Ala | T946A, S1004A | +++ | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q; Fig. 5 |

| JK>Asp | T946D, S1004D | − | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q; Fig. 5 |

| N>Ala | S56A, S72A | +++++ | +++++ | Highly conserved, N-terminal S/T hydrophobic; Fig. 6 |

| N>Asp | S56D, S72D | − | ± | Highly conserved, N-terminal S/T hydrophobic; Fig. 6 |

| L>Ala | T1865A | +++ | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material |

| L>Asp | T1865D | +++ | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q; see Fig. S2 |

| LZ>Ala | S1470A, S1546A | +++++ | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q within LRR; see Fig. S2 |

| LZ>Asp | S1470D, S1546D | +++++ | +++++ | Highly conserved S/T-Q within LRR; see Fig. S2 |

| Lys>Arg | K3752R | − | − | Conserved K in kinase domain (22) |

| Asp>Ala | D3921A | − | − | Putative catalytic aspartate |

−−−, increased radiosensitivity compared to that of vector-only controls.

DNA-PKcs expression plasmids, including mutations at the JK cluster (T946 and S1004), T1865 (L site), the N-terminal (N) cluster (S56 and S72), and the leucine zipper (LZ) cluster (S1470 and S1546), were derived as follows. All mutants were confirmed by sequence analysis. All mutant forms are listed in Table 1. To make the JK and T1865 mutants, the wild-type expression plasmid was initially digested with KasI, and a 4.5-kb segment of the DNA-PKcs cDNA was isolated and subcloned into pUC19. The aspartic acid and alanine substitutions were performed by site-directed mutagenesis using the following oligonucleotides and their complements: T946D top, 5′GTTGGGCAAAGCTGATCAGATGCCAGAA3′; S1004D top, 5′CAACAAGAAATTCGAAGATCAGGATACTGTT3′; T1865D top, 5′TCTACCTTTGATGATCAAATCACCAGG3′; T946A top, 5′GTTGGGCAAAGCTGCTCAGATGCCAGAA3′; S1004A top, 5′CAACAAGAAATTCGAAGCTCAGGATACTGTT3′; and T1865A top, 5′TCTACCTTTGATGCTCAAATCACCAGG3′.

The N mutations were constructed (mutating both sites simultaneously, with “>” indicating the site mutations) from a 2-kb fragment of the N terminus of the human DNA-PKcs cDNA and subcloned into the PCR2.1 plasmid. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the following oligonucleotides: N>Asp top, 5′CAATACTGTTGAGATCCTTCCGGACAAATACAAGCAAACCGAAATCTCTGGAAAAAACTAGATCTGTCTGTAATGCCAG3′, and N>Ala top, 5′CAATACTGTTGAGTGCCTTCCGGACAAATACAAGCAAA CCGAAATCTCTGG AAAAAACTAGTGCTGTCTGTAATGCCAG3′. The LZ mutants were constructed using the following oligonucleotides: S1470D top, 5′GGGCTTCTGCATAATATTTTACCGGATCAGTCCACAG3′; S1546D top, 5′CGGCGTCCTTGGGCAGCGACCAGGGTAGCGTCATCC3′; S1470A top, 5′GGGCTTCTGCATAATATTTTACCGGCTCAGTCCACAG3′; and S1546A top, 5′CGGCGTCCTTGGGCAGCGCACAGGGTAGCGTCATCC3′.

I-SceI-induced HR assay.

The peCFPN1 HR substrate (a generous gift from David Roth, NYU, New York, NY) (24) was introduced into V3, XR-1, or xrs6 cells by FuGene transfection, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN), and single clones were isolated. A single clone that could be reproducibly induced to express cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) by transfection of the I-SceI expression plasmid (as ascertained by flow cytometry) was chosen for further study. “Bulk” HR assays were performed by transfecting the appropriate reporter cell strain with 2 μg I-SceI expression plasmid (which carries a blasticidin resistance gene) with 6 μg (or the quantity indicated) of DNA-PKcs, XRCC4, or Ku86 expression plasmid or vector-only plasmid. Two days after transfection, cells were subjected to blasticidin selection (5 μg/ml) and cultured continuously in blasticidin-containing media for 14 to 21 days. CFP expression was monitored by fluorescence microscopy, and the percentage of cells expressing CFP was quantified by flow cytometry. Individual DNA-PKcs-expressing clones were derived in the V3-CFP-HR reporter strain by cotransfecting DNA-PKcs expression plasmids (20 μg) with a plasmid that encodes puromycin resistance (1 μg). Individual clones were selected, DNA-PKcs expression was assessed by immunoblotting, and isolated clones were selected for further study. HR was assessed in individual clones by transfecting 2 μg of the I-SceI expression plasmid or vector alone. Cells were subjected to blasticidin selection as described above, and the percentage of cells expressing CFP was quantified by flow cytometry.

Immunoblotting.

Cell extracts or DNA-cellulose binding fractions were analyzed after electrophoresis on 4.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. To detect total DNA-PKcs, a monoclonal antibody raised against DNA-PKcs (42-27, a generous gift from Tim Carter, St. Johns University, New York, NY) was used as the primary antibody. A polyclonal rabbit anti-ATM antibody that recognizes hamster, mouse, human, and monkey ATMs was utilized (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) to detect ATM. Phospho-specific antibodies that recognize phosphorylated S2056 (R site; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), T946 (J site), S72 (N2 site), or S3205 (M site) were utilized to detect phosphorylations at specific sites.

Phospho-specific antiserum against phospho-J was raised in rabbits using the phosphopeptide LGKA[pT]QMPEGGQC, a region covering the J site, and purified by peptide affinity (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). Phospho-specific antiserum against phospho-S72 was raised in rabbits using the phosphopeptide DFGLLVFVRK[pS]LNSIEFRECR, a region covering the N2 site, and purified by peptide affinity (PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO). The phospho-specific antibody to S3205 was raised in sheep against the phosphopeptide KKKPEDN[pS]MNVD and purified as described previously (16).

For immunoblotting to detect phosphorylated S3205, extracts were prepared in the presence of protein phosphatase inhibitors. DNA-PKcs was immunoprecipitated using monoclonal Ab 42-27, and blots were probed with a phosphospecific antibody to serine 3205 and then stripped and reprobed for detection of total DNA-PKcs. HeLa cells were pretreated with 5 μM Ku55933 (ATM inhibitor) or 8 μM Nu7441 (DNA-PK inhibitor) for 45 min and then either mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 Gy ionizing radiation (IR). Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were made using NTEN lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1% [vol/vol] NP-40) containing 1 μM microcystin-LR, 0.2 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 μg/ml pepstatin A. DNA-PKcs was immunoprecipitated from 2 mg WCE using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (DPK1). Immunoprecipitates (IPs) were washed seven times with 1 ml of NTEN lysis buffer containing 0.25% NP-40. Samples were boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer, run on 8% gels, and transferred to PVDF. DNA-PKcs null CHO cells (V3) stably transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)–DNA-PKcs were treated with vehicle alone, Nu7441, or Ku55933, as indicated, and then either mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 Gy IR (1 h of recovery). Cells were lysed in NTEN buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. DNA-PKcs was immunoprecipitated from 2 mg of WCE using a mouse anti-GFP antibody (ab1218; Abcam). Filters were probed with the p3205 phospho-specific DNA-PK antibody and then stripped and reprobed for DNA-PK using monoclonal antibody 42-27.

DNA cellulose binding and DNA-PK kinase assays.

DNA-cellulose pulldowns were done by incubation of 1 mg whole-cell extract (WCE) from V3 transfectants with 50 μl DNA-cellulose beads (Amersham) in buffer A (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) containing protease inhibitors (EDTA free; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 4°C for 1 h with continuous rocking. After incubation, beads were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with buffer A and analyzed by immunoblotting. DNA-PK catalytic assays were done by modifying the assay described by Finnie et al. (17) and modified by Kienker et al. (22).

Mapping DNA-PK phosphorylation sites in Artemis.

A baculovirus encoding the Artemis endonuclease (His tagged) was generated (using cDNA cloned from human fibroblast cDNA). Artemis was purified by Ni+ agarose affinity (as previously described for His-tagged XRCC4 [42]), and in vitro kinase reaction mixtures containing purified DNA-PK and Artemis were assayed in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) 100 mM KCl, 20 μg/ml calf thymus DNA, and 100 μM ATP. Phosphorylated Artemis was recovered from SDS-PAGE gels and trypsinized, and phosphorylated peptides were identified by mass spectrometry.

Clonogenic survival assays.

V3 transfectants were exposed to 0, 2, 4, or 6 Gy of ionizing radiation using a 60Co source in α-MEM and then immediately seeded in complete medium at cloning densities (1,000 cells/100-mm2 dish). For zeocin sensitivity, V3 transfectants were plated at cloning densities in the indicated dosages of zeocin. After 7 days, cell colonies were stained with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet in ethanol, and colony numbers were assessed. Survival was plotted as the percent survival compared to that of untreated cells.

RESULTS

Inhibition of HR by DNA-PK is titratable.

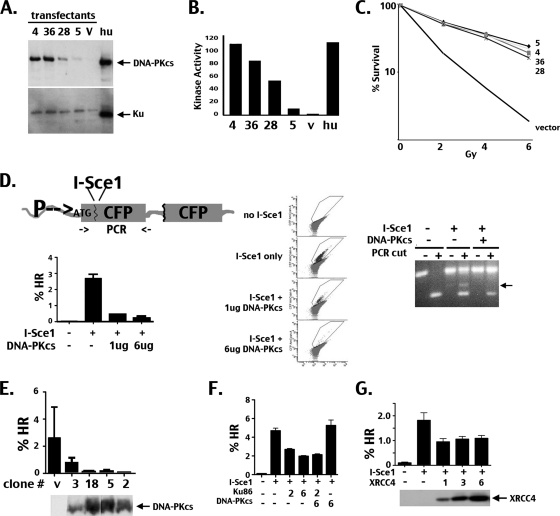

To address the cellular consequences of high DNA-PK levels, a panel of isogenic cell strains with a wide range of DNA-PK activity was engineered (Fig. 1 A) using the V3 DNA-PKcs CHO mutant cell strain. Individual isogenic clones were chosen that maintained consistent DNA-PKcs expression levels and that varied from one another in DNA-PKcs expression. (In Fig. 1, numbers refer to individual clones, and only four of a much larger panel are depicted.) Even though DNA-PK enzymatic activity requires both DNA-PKcs and Ku, endogenous Ku levels are not limiting (at least with these levels of DNA-PKcs) because increasing DNA-PKcs levels resulted in markedly increased enzymatic activity, with ∼20-fold differences in different clones (Fig. 1B). However, this marked increase in DNA-PK enzymatic levels did not enhance radioresistance whatsoever (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Radioresistance is not dependent on relative DNA-PK expression, but the rate of HR is titratable. (A and B) Increasing expression of DNA-PKcs results in increased DNA-PK activity in V3 transfectants; thus, Ku is not limiting. (A) Immunoblot of cell extracts (50 μg) from V3 transfectants (V) expressing various levels of human DNA-PKcs compared to extracts from a human fibroblast line (hu) (10 μg). The slight difference in the electrophoretic mobilities of human and hamster Ku has been shown previously (18). (B) DNA-PK activity of V3 transfectants compared to that of a normal human fibroblast line. (C) V3 transfectants expressing a wide range of DNA-PK activity are similarly radioresistant. Relative survival of V3 transfectants expressing various levels of human DNA-PKcs after exposure to IR, as indicated. (D) DNA-PK's ability to inhibit HR is dose dependent, as assessed in a bulk transfection assay. (Top, left) CFP HR substrate diagram. Positions of PCR primers (denoted by an arrow) are shown in the diagram of the HR substrate. (Bottom, left) A V3 transfectant harboring the CFP HR substrate was transfected with or without an I-SceI expression plasmid or the appropriate control as well as with increasing concentrations of an expression plasmid encoding human DNA-PKcs. Transfected cells were selected by blasticidin resistance. Relative HR (percent CFP expression) was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). (Middle) Representative histograms from FACS analyses. (Right) The status of the I-SceI substrate was also ascertained by PCR of DNA isolated from bulk transfections. (E) DNA-PK's ability to inhibit HR is dose dependent, as assessed with individual stable DNA-PKcs transfectants. The V3-CFP cell strain was transfected with a human DNA-PKcs expression plasmid. Individual clones stably expressing a range of human DNA-PKcs's (as determined by Western analysis [bottom]) were subsequently transfected with an I-SceI expression plasmid and selected by blasticidin resistance. Relative HR (top) was determined by FACS. (F and G) The CFP HR substrate was transfected into xrs6 cells (deficient in Ku86) and XR-1 cells (deficient in XRCC4), and stable clones were isolated and analyzed for their ability to express CFP after I-SceI transfection. These reporter lines were transfected with or without an I-SceI expression plasmid with or without increasing concentrations of expression plasmids encoding human Ku86 and DNA-PKcs or mouse XRCC4, as indicated. Ku86's ability to suppress HR is titratable, but XRCC4's ability to suppress HR is not titratable.

We have previously (7) employed an I-SceI-induced neo cassette HR substrate that was stably integrated into V3 cells (developed by others [1]). In those assays, single clones expressing DNA-PKcs or its variants (two clones for each mutant) were assayed for successful HR by gain of neomycin resistance. In the process of screening the large panel of wild-type-expressing DNA-PKcs clones studied here, it became apparent that this neo-based assay does not always accurately assess HR. This was revealed by reconstruction experiments that assessed the accuracy of retrieving authentic neomycin-resistant clones from large populations of neomycin-sensitive cells (not shown). In sum, the problems with the assay are likely (or at least partially) explained by difficulties in retrieving small percentages of neomycin-resistant cells from large populations and in appropriately selecting only neomycin-resistant cells from populations with large numbers of resistant clones. To avoid the problems associated with drug selection, a fluorescence-based assay was employed using a substrate that allows assessment of the frequency of HR induced by the homing endonuclease I-SceI (diagrammed in Fig. 1D, top) (8). This substrate contains two nonfunctional copies of the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) gene. Although the first copy has an active promoter, the CFP open reading frame is disrupted by stop codons within an I-SceI target site that has been inserted into the CFP open reading frame. The second CFP copy lacks both a promoter and an ATG start codon. Thus, either NHEJ (no CFP expression) or HR (CFP expression) can repair the I-SceI breaks. However, in this assay, I-SceI expression is selected for (by blasticidin sensitivity) throughout the experiment, so as with other I-SceI-based HR assays, we are measuring the percentage of cells that repair I-SceI breaks by HR over the ∼2-week assay. Questions of kinetics of HR cannot be addressed using this assay. This substrate was stably introduced into V3 cells; several clones were selected and tested for induction of CFP after I-SceI transfection. A single substrate clone that could be reproducibly induced to express CFP by I-SceI transfection was selected for all subsequent experiments.

The V3-CFP HR reporter cell strain was transfected (“in bulk”) with a vector that expresses I-SceI as well as with different concentrations of a plasmid that expresses wild-type DNA-PKcs (Fig. 1D). After approximately 2 weeks (with constant selection for I-SceI expression via blasticidin resistance), the cells were assayed for CFP expression by flow cytometry as a measure of HR frequency. As can be seen, I-SceI induces robust CFP expression that is markedly inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion by cotransfection of increasing amounts of wild-type DNA-PKcs. To further characterize the efficacy of the substrate, PCR was performed with DNA isolated from transfectants to assess recombination of the integrated substrate (Fig. 1D, right). In cells not transfected with I-SceI, a single PCR fragment that spans the first copy of the substrate is apparent; this PCR product is entirely restricted by I-SceI. Amplification of DNA from cells transfected with I-SceI generates two PCR products; the size of the second, smaller product (Fig. 1D, right, arrow) is consistent with deletion of the I-SceI target site and repair by HR, and the weak intensity of the band is consistent with the ∼2.5% HR frequency observed in cells lacking DNA-PKcs. Detection of the HR-specific band is greatly reduced in PCRs with cells cotransfected with DNA-PKcs, consistent with the marked reduction in HR in cells cotransfected with the DNA-PKcs expression vector. Further, in PCRs with cells expressing I-SceI, a major fraction of the larger product is resistant to I-SceI cutting, consistent with imprecise end joining (presumably by a-NHEJ in cells lacking DNA-PKcs or by both c-NHEJ and a-NHEJ in cells expressing DNA-PKcs). The ratio of NHEJ-repaired substrates (i.e., ratio of the number of I-SceI-resistant PCR product to that of smaller HR products) is consistent with reports that NHEJ predominates over HR in rejoining I-SceI breaks in cultured mammalian cells (27).

The type of HR reporter assay utilized here is often done by generating stable individual clones expressing factors that alter HR. Therefore, we repeated the assay using the strategy of first generating clonal DNA-PKcs transfectants (from the original substrate clone) with various levels of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 1E); as can be seen, the level of HR induced is inversely correlated with the amount of DNA-PKcs expression. In our hands, individual V3 clones (expressing the same DNA-PKcs construct derived from the same HR reporter clone) can recombine the HR reporter at somewhat different rates. For example, compare the HR rates in the two vector control clones in Fig. 2 B. For that reason, in this report we have assessed HR in V3 cells not only in multiple individual clones expressing the same construct but also in bulk transfections of the reporter V3 cell clone (cotransfecting I-SceI and DNA-PKcs expression constructs). From these experiments, we conclude that DNA-PK's inhibition of HR is titratable.

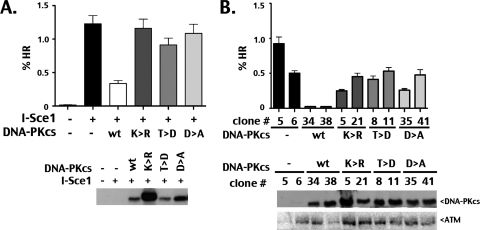

Fig. 2.

DNA-PK's kinase activity is required to inhibit HR. (A) The V3-CFP cell strain was cotransfected in bulk with a vector expressing I-SceI and the indicated DNA-PKcs construct. (Top) The average HR frequencies are shown. (Bottom) DNA-PKcs protein expression levels were confirmed by Western blotting. wt, wild type. (B, top) The average frequency of I-SceI-induced HR in individual clones expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs or the three kinase-inactivating mutants is shown. (Bottom) Western analysis documents DNA-PKcs and ATM expression levels in individual clones.

To determine whether expression of other NHEJ factors also modulate HR levels in a titratable fashion, the CFP-HR substrate was introduced into both the xrs-6 cell strain (deficient in Ku86) and the XR-1 cell strain (deficient in XRCC4), and clones from each cell line that could reproducibly be induced to express CFP by I-SceI transfection were isolated. Consistent with previous reports, a reduction in the HR frequency results from restoration of competent NHEJ in cells with defects in Ku or XRCC4 (Fig. 1F and G). As with DNA-PKcs, reduction in HR by restoring Ku expression is dose dependent. However, even with high levels of Ku86 transfection, HR is reduced only by a factor of 2, which likely reflects the fact that Ku function requires both endogenous Ku70 and transfected Ku86 and that endogenous Ku70 is limiting and/or DNA-PKcs is limiting. Cotransfection of the DNA-PKcs expression plasmid further reduced HR when transfecting 2 μg of the Ku86 expression plasmid. However, transfection of the DNA-PKcs expression plasmid alone had no effect on cells not transfected with the Ku86 plasmid, so as one would expect, DNA-PKcs's effect on HR is entirely dependent on Ku. Although XRCC4 expression abates HR levels in the XR-1 cell strain, this effect is not titratable.

DNA-PK's enzymatic activity is required for its ability to repress homologous recombination.

To better understand the requirements for DNA-PK's ability to suppress HR, we tested whether DNA-PK's kinase activity is necessary for its ability to modulate the frequency of I-SceI-induced HR. The V3-CFP HR reporter cell strain was transfected with the I-SceI expression vector alone or with expression vectors encoding either wild-type DNA-PKcs or one of three DNA-PKcs-inactivating mutants (Fig. 2A). As expected, I-SceI induced robust levels of CFP expression (∼75-fold increase over that induced by control transfectants). Cotransfection of an expression plasmid encoding wild-type DNA-PKcs reduced the frequency of I-SceI-induced HR by approximately 4-fold compared to that induced by I-SceI alone. In contrast, none of the three kinase-inactive mutants altered HR levels compared to those altered by transfectants with the I-SceI plasmid alone. Each of these mutants is distinct and affects enzymatic inactivation differently; the phenotypes associated with these mutants are summarized in Table 1. A Lys>Arg mutant at amino acid 3752 (K3752R) was designed to disrupt ATP binding (22, 23), although the precise ATP-binding site has not been determined in DNA-PKcs. An Asp>Ala mutant at amino acid 3921 (D3921A) targets the likely catalytic aspartate in the kinase domain (23). A Thr>Asp mutation at amino acid 3950 (T3950D) renders the kinase inactive by mimicking phosphorylation within the putative activation loop in the kinase domain (14). HR was also assessed in individual clones expressing either wild-type DNA-PKcs or each of the kinase-inactivating DNA-PKcs mutants with completely analogous results (Fig. 2B). It has been shown that DNA-PKcs-deficient cells have decreased ATM expression (31); however, differences in HR rates in different clones expressing the same DNA-PKcs construct do not correlate with ATM levels, as has been suggested by others (37). Based on these results, we conclude that DNA-PK's catalytic activity is required for its ability to repress HR. However, these results were unanticipated because a previous study that used chemical inhibitors of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity in HR assays showed that suppression of DNA-PK's kinase activity markedly inhibited HR (1). To address the discrepancy in the effects on HR between mutational and chemical ablation of DNA-PK activity, HR was assessed in the V3-CFP cell strains that stably express either wild-type or no DNA-PKcs (see Fig. S1A and C in the supplemental material) in the presence or absence of the DNA-PK kinase inhibitor IC86621 (the inhibitor utilized by Allen et al. [1]) or Nu7026. In contrast to Allen et al., we find that the low levels of HR observed in cells expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs are increased by approximately 2-fold in cells treated with IC86621 or Nu7026. Still, HR rates in cells expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs that were treated with these inhibitors did not approach the level observed in cells deficient in DNA-PKcs. However, both inhibitors (supposed DNA-PK-specific reagents) significantly depressed HR in cells that lack DNA-PKcs; the inhibition of HR in cells lacking DNA-PKcs is likely attributed to marked growth inhibition by these drugs (see Fig. S2B and D in the supplemental material). (It should be noted that expression of catalytically inactive DNA-PKcs in V3 cells does not affect cell growth.) In sum, we conclude that DNA-PK's enzymatic activity is absolutely requisite to its ability to inhibit HR.

DNA-PK's enzymatic activity is not sufficient to limit HR; however, the requirement of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity for its ability to inhibit HR is not just a reflection of failed NHEJ.

The primary physiologic effect of lacking enzymatic activity of DNA-PK is failure of NHEJ. The fact that enzymatically inactive DNA-PK does not inhibit HR implies that a DNA-PK phosphorylation event is required to establish and maintain an NHEJ complex (which blocks HR), leaving the straightforward explanation that increased HR in cells deficient in DNA-PK's kinase activity is simply because of failed NHEJ. An alternative explanation is that DNA-PK phosphorylation of a particular substrate enforces inhibition of HR or constrains DNA breaks to the NHEJ pathway. Although DNA-PK has been shown to phosphorylate many substrates both in vitro and in vivo, the only phosphorylation substrate of DNA-PK that has been demonstrated to result in a physiological alteration in NHEJ efficiency is autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs itself (reviewed in reference 28). We considered that the requirement of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity to inhibit HR might be explained by the requirement of a particular autophosphorylation event. We have studied numerous autophosphorylation-ablating and -mimicking DNA-PKcs mutants that vary in catalytic capacity, NHEJ proficiency, and ability to regulate end processing during NHEJ. To gain insight into whether successful NHEJ or phosphorylation of a particular substrate explains why only kinase-active DNA-PK inhibits HR, HR was assessed in cells expressing eight different DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation site mutant types (summarized in Table 1). These eight mutants alter a total of 20 potential or defined autophosphorylation sites. All were studied as both phosphoblocking (S/T>Ala) and phosphomimicking (S/T>Asp) substitutions. Table 1 provides a brief summary of the phenotypes associated with mutating these phosphorylation sites, including their ability to reverse radiosensitivity of the V3 cell strain, enzyme catalytic activity, and characteristics of end processing associated with each autophosphorylation site or cluster. The NHEJ and enzymatic efficiencies are also indicated beside each experimental point in Fig. 3. As noted above, DNA-PKcs phosphorylations are complex and occur on numerous sites. We have shown previously and below that the ABCDE, PQR, and JK sites function as clusters; for brevity (and consistency with previous publications), clusters are referred to by previously ascribed alphabetic names. Single phosphorylation sites will be referred to as the amino acid position and substitution, although the alphabetic names used previously for these sites are also listed in Table 1. The ABCDE cluster, PQR cluster, and T3950 mutants have been described previously (10, 12, 14). The S3205, T1865, LZ cluster, JK cluster, and N cluster mutants are described below.

Fig. 3.

DNA-PK's enzymatic activity is not sufficient to limit HR; however, the requirement of DNA-PK's enzymatic activity for its ability to inhibit HR is not just a reflection of failed NHEJ. (A) Diagram of the DNA-PKcs coding sequence, showing positions of phosphorylation sites and catalytic sites mutated in this study. (B and C) The V3-CFP cell strain was cotransfected in bulk with a vector expressing I-SceI and the indicated DNA-PKcs construct. The average HR frequencies are shown. Cellular phenotypes associated with each mutant are indicated but are described in more detail in Table 1, Fig. 4 to 6, and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. (B) Data are grouped based on the ability of each mutant to complement the V3 radiosensitive phenotype. White bars, no complementation; gray bars, intermediate complementation; black bars, full complementation. DNA-PKcs protein expression levels were confirmed by Western analysis (not shown). All except PQR>Asp (denoted by an asterisk) expressed DNA-PKcs stably and at levels similar to that of the wild type. (C) Data are grouped to compare pairs of alanine mutants (gray bars) and aspartic acid mutants (black bars). (D) The V3-CFP cell strain was cotransfected in bulk with a vector expressing I-SceI and the indicated DNA-PKcs construct. (Left) Average HR frequencies; (right) relative DNA-PKcs and ATM levels in each transfection.

The data shown in Fig. 3 are presented in two ways: pairing the different phosphomimicking (black bars) and -blocking (gray bars) mutants (Fig. 3C discussed below) or grouping the mutants based on their efficiency in reversing the V3 radiosensitive phenotype (Fig. 3B). All of these mutants (except the T1865 and LZ mutants) have been studied as individual clones, with completely analogous results (data not shown). As one might expect, most of the NHEJ-proficient mutants that fully complement V3's radiosensitive phenotype have markedly reduced HR (Fig. 3B, black bars). The exception to this is the PQR>Asp mutant, which completely reverses the V3 radiosensitive phenotype and VDJ recombination deficits. The phenotype of severely limiting end processing associated with the PQR phosphomimic would actually make these sites candidates for limiting HR. However, as shown in our previous studies, it has been impossible to isolate cells that express more than minimal levels of either the complete PQR>Asp mutant or partial mutants (PQ>Asp or R>Asp) (10) (not shown); with these mutants, expression is rapidly lost in V3 cells over the course of several weeks. Thus, relatively high HR in cells expressing PQR>Asp is likely the result of extremely low DNA-PKcs expression levels. Another consideration is that PQR>Asp robustly blocks end processing; as a result, successful NHEJ mediated by the PQR>Asp mutant will almost always restore the I-SceI site, allowing recutting by I-SceI and an increased probability of HR as PQR>Asp expression diminishes over the course of the experiment. Thus, it seems unlikely that PQR phosphorylation promotes HR.

Five of the mutants studied here only partially reverse V3's radiosensitive phenotype and VDJ recombination deficits (most-to-least complementation, T1865A, T1865D, PQR>Ala, JK>Ala, T3950A). All five of these can be expressed at high levels, and all inhibit HR reasonably well. We conclude that DNA-PKcs mutants that can be expressed at wild-type levels and can mediate NHEJ (albeit at a somewhat diminished level) also efficiently inhibit DSB-induced HR. Thus, these data suggest that “inhibited” HR is simply a reflection of successful NHEJ.

Additionally, most of the NHEJ-defective mutants (i.e., those that do not complement V3 radiosensitivity) utilize HR at frequencies similar to those of cells that lack DNA-PKcs (Fig. 3B, white bars). This is most likely explained by each of these NHEJ-defective mutants undergoing autophosphorylation-induced dissociation after failed NHEJ, allowing HR access to the I-SceI-induced break. However, one mutant, N>Asp, does not complement V3 radiosensitivity but inhibits HR slightly more than wild-type DNA-PKcs. Thus, in this case, failed NHEJ does not correlate with increased HR. The N>Asp mutation impairs kinase activation. Since the N>Asp mutant inhibits HR well, one might consider whether phosphorylation of this site is important in regulating HR. However, the N>Ala mutant also effectively inhibits HR; thus, N phosphorylation is not required for HR inhibition. Moreover, combining the N>Asp mutation with kinase inactivation allows for robust HR (Fig. 3D, left). Thus, although N phosphorylation may contribute to inhibition of HR, N phosphorylation is not sufficient or required to inhibit HR. Even more, the fact that N>Asp and N>Asp/K3752R are similarly impaired in NHEJ (data not shown) suggests that a DNA-PK-mediated phosphorylation event actively impedes HR. In addition, differences in relative HR for the kinase-impaired mutant (N>Asp) or kinase-inactive mutants (K3752R and N>Asp/K3752R) do not correlate with ATM expression (Fig. 3D, right).

Finally, in the panel of mutants studied here, only the T3950D phosphorylation mutant completely lacks enzymatic activity and, as discussed above, does not inhibit HR. Several of these phosphorylation mutants do not inhibit HR or inhibit HR less effectively than wild-type DNA-PKcs (ABCDE>Ala, JK>Asp, ABCDE>Asp, PQR>Ala, and PQR>Asp), even though each has wild-type enzymatic activity. From these studies, we conclude that DNA-PK enzymatic activity is required but not sufficient to inhibit HR and that in most cases (but not all), failed NHEJ results in increased HR.

Phosphomimicking and phosphoablating mutations of phosphorylation sites that affect HR should have opposing HR phenotypes.

We would expect that if a particular DNA-PK-mediated autophosphorylation event were critical to DNA-PK's ability to impede HR, phosphoblocking mutations should enhance HR, whereas phosphomimicking mutations of the same site should inhibit HR. Similarly, if an autophosphorylation event enhances HR, one would expect decreased HR in cells expressing alanine mutants of that site and enhanced HR in cells expressing phosphomimicking mutations of the same site. Of the eight pairs of mutants studied, only three (PQR, JK, and T3950) have clearly opposing effects on HR (as with Asp versus Ala substitutions).

The ABCDE and PQR clusters are the most well-studied DNA-PKcs phosphorylation sites. Whereas phosphorylation within ABCDE promotes end processing during VDJ recombination or of an I-SceI-induced break, phosphorylation within PQR limits end processing (10). Phosphorylation within both of these clusters can occur in trans (29), although it is possible that cis phosphorylations can occur as well. We have previously utilized the neo-based substrate developed by Allen et al. (1) to study HR in cells expressing the ABCDE>Ala and PQR>Ala autophosphorylation mutants and found that blocking the ABCDE phosphorylation limited HR, whereas blocking PQR phosphorylation allowed more HR than wild-type DNA-PKcs. However, with the CFP-based assay, although HR in cells expressing the PQR>Ala mutant was consistently higher than in cells expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs, HR in cells expressing the ABCDE mutant was also substantially increased. This was observed in cells transfected “in bulk” (Fig. 3C) as well as in individual clones (not shown). We attribute the discrepancy in our conclusions here with those in our previous reports (7, 10) to problems associated with the neomycin-based HR assay as discussed above. In our previous study, we also showed that cells expressing DNA-PKcs that cannot phosphorylate ABCDE are substantially more radiosensitive than cells lacking DNA-PKcs; this phenotype was also observed in cell clones tested here harboring the CFP substrate (data not shown). Similarly, cells expressing the ABCDE>Ala mutant displayed markedly reduced end processing of I-SceI breaks, consistent with our previous conclusions (data not shown).

Autophosphorylation within the putative activation loop promotes HR by inactivating NHEJ.

Our laboratories have previously characterized autophosphorylation within the putative activation (or T) loop of DNA-PKcs. Autophosphorylation of T3950 (T site) within the kinase domain inactivates the enzyme but does not induce kinase dissociation (14). T3950 phosphorylation occurs both in vitro and in response to DNA damage in living cells. Unlike most of the other mutant pairs studied, shown in Fig. 3, the T3950A and T3950D mutations have quite distinct effects on HR. Blocking T phosphorylation by alanine substitution reduces NHEJ proficiency (as measured by radioresistance and VDJ recombination assays). Still, the T3950A mutant is completely proficient in inhibiting HR (Fig. 3), and we conclude that depressed NHEJ is not sufficient to promote increased HR. As shown above, the phosphomimic of T3950, which lacks catalytic activity, does not inhibit HR, reflecting the fact that enzymatic activity is required for DNA-PK suppression of HR. We suggest that in living cells, T3950 phosphorylation provides a mechanism to disrupt NHEJ and promote HR; this would be of clear benefit if DNA-PK were targeted to certain types of DNA damage (for instance, to cross-links or to a single DNA end, as occurs at collapsed replication forks). It is tempting to speculate that increased radiosensitivity of cells that cannot phosphorylate T3950 might be the result of an impaired ability to promote HR by appropriate inactivation of DNA-PK by activation loop autophosphorylation.

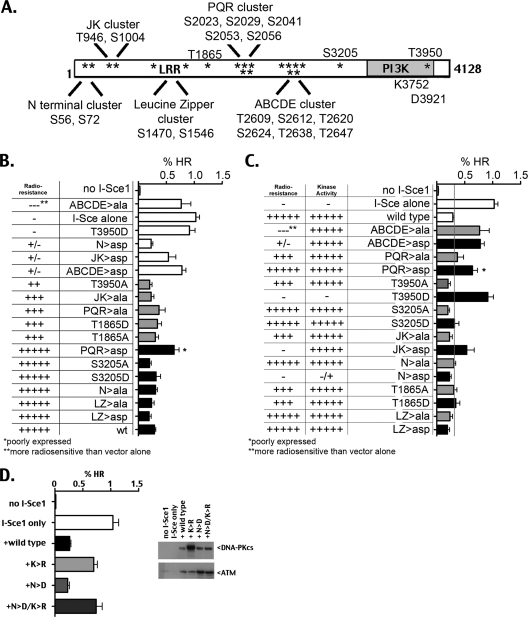

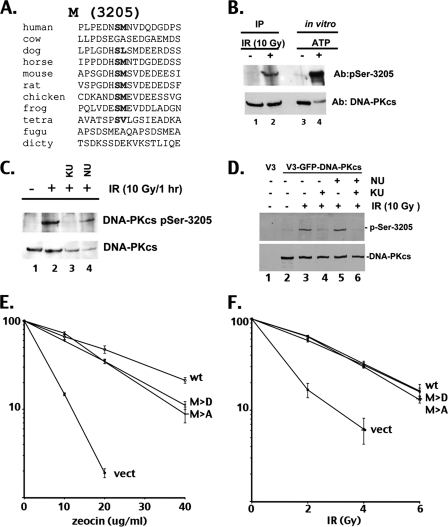

ATM targets S3205 in vivo, but its phosphorylation does not affect NHEJ and has a minimal effect on HR proficiency.

We have previously defined S3205 (referred to as site M) as an in vitro DNA-PK autophosphorylation site (16) and studied this site in conjunction with the ABCDE, PQR, and T3950 sites (14). This S/hydrophobic (hyd) site is strongly conserved in vertebrate DNA-PKcs (Fig. 4 A) and has been identified as an in vivo phosphorylation site in numerous genome-wide phosphoproteomics screens (reviewed in reference 13). More recently, S3205 has been identified as an IR-induced phosphorylation site in genome-wide analysis of sites phosphorylated in the DNA damage response (3; S. Elledge, personal communication) and more recently as an ATM target in response to DNA damage (4). Characterization of the ATM versus DNA-PK dependence of S3205 phosphorylation was of particular interest because of previous controversy over which of these kinases predominately phosphorylate the ABCDE sites (6, 29). To more fully characterize phosphorylation of S3205, a phospho-specific reagent was generated. Interestingly, S3205 is phosphorylated in an ATM-dependent manner in vivo (Fig. 4B to D). Although the ATM-specific inhibitor completely ablates IR-induced S3205 phosphorylation in both HeLa cells and V3 transfectants expressing DNA-PKcs, the DNA-PK inhibitor has little effect. Both the S3205A and S3205D mutants completely reverse the V3 radiosensitive phenotype (Fig. 4F), although both have a modestly reduced ability to restore resistance to zeocin (Fig. 4E). Both the S3205A and S3205D mutants strongly inhibit HR; however, the S3205D mutant is a slightly less potent inhibitor, perhaps suggesting that ATM-dependent phosphorylation of the S3205 site might promote HR (Fig. 3), yet this effect is minimal. Thus, although the S3205 site is phosphorylated in living cells in response to DNA damage by the ATM kinase, this phosphorylation event does not alter radioresistance and has only a small positive effect on the rate of HR and a small negative effect on zeocin resistance.

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation of S3205 in response to IR is mediated primarily by ATM but does not affect NHEJ. (A) Sequence alignment of DNA-PKcs from 11 species in the region adjacent to S3205. dicty, Dictyostelium species. (B) For lanes 1 and 2, HeLa cells were mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 Gy IR, harvested after 1 h, and probed with the antisera specific for phospho-S3205 or with 42-27 to detect total DNA-PKcs, as indicated. For lanes 3 and 4, purified DNA-PKcs was incubated under mock phosphorylation conditions without (−) or with (+) ATP as indicated. Note that the faint band in lane 4 results from antibody blocking due to strong binding of the phospho-specific antibody. (C) HeLa cells were pretreated with 5 μM Ku55933 (ATM inhibitor) or 8 μM Nu7441 (DNA-PK inhibitor) for 45 min and then either mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 Gy IR and probed for phospho-S3205 or total DNA-PKcs. (D) DNA-PKcs null CHO cells (V3) were stably transfected with GFP-DNA-PKcs. Cells were treated with vehicle alone, Nu7441, or Ku55933, as indicated, and then either mock irradiated or irradiated with 10 Gy IR (1 h of recovery). Anti-GFP immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted to detect phospho-S3205 or total DNA-PKcs. (E and F) V3 transfectants expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs, the S3205A or S3205D mutants, or no DNA-PKcs were plated at cloning densities into complete media with increasing doses of zeocin (E), as indicated, or irradiated with increasing doses of IR and plated into complete media at cloning densities (F). Colonies were stained after 7 days, and percent survival was calculated. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEM).

Phosphomimics of five additional S/T sites within DNA-PKcs impair NHEJ.

We have previously shown that DNA-PKcs with 13 S/T>Ala substitutions of the ABCDE, PQR, S3205, and T3950 sites still undergoes autophosphorylation-induced kinase dissociation at rates similar to those of the wild-type kinase (14). Thus, we surmise that additional autophosphorylation sites are likely to be physiologically important. Of the sites studied to date (defined by either mass spectrometric experiments and/or phospho-specific reagents), the sites that impart the strongest NHEJ deficits (when ablated or mimicked) are also extremely well conserved. We examined sequence alignments of DNA-PKcs homologues from multiple species (human, cow, dog, horse, mouse, rat, chicken, frog, puffer fish, and Dictyostelium). Of 512 S/T residues within human DNA-PKcs, ∼180 are highly conserved. Serines and threonines, followed by glutamines (S/T-Q sites), are the preferred DNA-PK, ATM, and ATR targets, although DNA-PKcs can also efficiently phosphorylate serines and threonines, followed by hydrophobic residues (S/T-hyd sites) (25). There are a total of 27 S/T-Q sites in human DNA-PKcs; of these, 11 are highly conserved (present in frog, chicken, rat, mouse, horse, dog, cow, and human). A total of 6 of those 11 sites have already been studied (ABCDE, PQR, or T3950 sites). Three of the remaining five sites are in the N-terminal half of the molecule. Our previous work has implicated the extreme N terminus (N-terminal 426 amino acids) as well as the leucine-rich region (LRR; first described as a leucine zipper) as being important for DNA-PK's ability to stably complex with Ku-bound DNA (14, 20, 43). We reasoned that phosphorylation within regions important for complex assembly might mediate kinase dissociation. Thus, we chose to study (by mutagenesis) seven additional sites that are strongly conserved S/T-Q or S/T-hydrophobic sites and are in regions important for DNA-PK complex stability. These are denoted T1865, LZ (leucine zipper cluster; S1470 and S1546), JK (JK cluster; T946 and S1004), and N (N-terminal cluster; S56 and S72).

The phenotypes of these mutants are summarized in Table 1 and are presented in Fig. 5 and 6 and also in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. Two strongly conserved S-Q target sites (S1471 and S1546, “LZ”) flank the LRR of DNA-PKcs (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Moreover, phosphorylation of both of these sites was observed using a mass spectrometry screen of autophosphorylated DNA-PKcs in vitro (Y. Yu and S. P. Lees-Miller, unpublished data). Additionally, the strongly conserved TQ 1865-1866 (T1865) site was observed in the same screen. However, neither phosphoblocking nor phosphomimicking mutations of either the LZ or T1865 sites significantly affect the ability of DNA-PKcs to (i) complement the radiosensitivity of V3 cells supporting VDJ recombination (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), (ii) inhibit HR (Fig. 3), or (iii) assemble onto Ku-bound DNA (see Fig. S2). We conclude that phosphorylation of these sites does not significantly affect either NHEJ or HR.

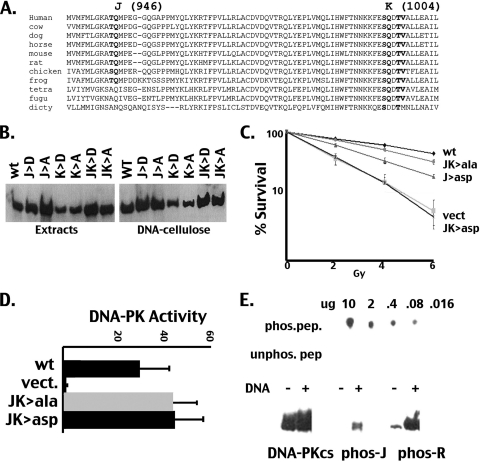

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of JK inhibits NHEJ but promotes HR and does not alter enzymatic activity. (A) Sequence alignment of DNA-PKcs from 11 species in the region adjacent to the “J” (T946) and “K” (S1004) phosphorylation sites. (B) Whole-cell extracts from cells expressing either single or combined J and K Ala or Asp mutants, as indicated, were “pulled down” onto DNA cellulose and analyzed by Western blotting. Relative DNA-PKcs levels in extracts compared to those in DNA-cellulose pulldowns are depicted. (C) V3 transfectants expressing either wild-type (wt) DNA-PKcs, the J>Asp, JK>Ala, or JK>Asp mutants, or no DNA-PKcs were irradiated as indicated and plated into complete media at cloning densities. Colonies were stained 7 days later, and the percent survival was calculated. Error bars represent SEM. (D) DNA-PK enzymatic levels were determined in extracts from V3 transfectants expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs, the JK>Ala or JK>Asp mutants, or vector control using a modification of the method described by Finnie et al. (17). Relative activity is depicted as the fold increase over no peptide as described previously (22). (E) In vitro phosphorylation of T946 (J site) was assessed with a phospho-specific antiserum. (Top) Increasing concentrations of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides were spotted onto PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with the phospho-specific reagent. (Bottom) In vitro kinase assays using whole-cell extracts from HEK293 cells in the presence or absence of DNA, as indicated, were analyzed by immunoblotting, using a monoclonal to human DNA-PKcs (42-27) and a phospho-specific reagent that recognizes phospho-T946 (J site) or phospho-S2056 (R site), as a control.

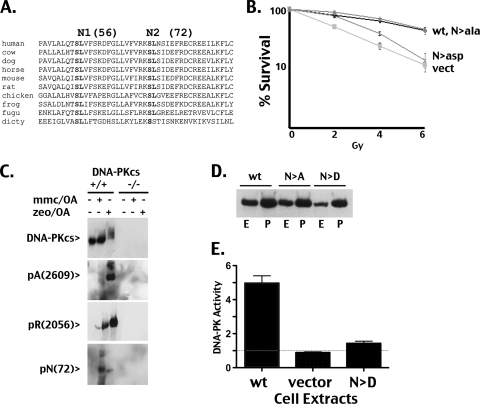

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation of “N” inhibits NHEJ and abrogates enzymatic activity but not complex assembly. (A) Sequence alignment of DNA-PKcs from 10 species in the region adjacent to the N1 (S56) and N2 (S72) phosphorylation sites. (B) V3 transfectants expressing either wild-type DNA-PKcs, the N>Ala or N>Asp mutants, or no DNA-PKcs were irradiated as indicated and plated into complete media at cloning densities. Colonies were stained 7 days later, and the percent survival calculated. Error bars represent SEM. (C) HCT116 cells expressing or lacking DNA-PKcs were treated or mock treated with okadaic acid (OA) and zeocin (zeo) or okadaic acid and mitomycin C (mmc), as indicated. Cells were harvested 1 h later, and cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody to DNA-PKcs (42-27) (top panel) and phosphospecific reagents for phospho-T2609 (A site) (second panel), phospho-S2056 (R site) (third panel), and phospho-S72 (N2 site) (bottom panel). (D) Whole-cell extracts from cells expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs or the N>Ala or N>Asp mutant were “pulled down” onto DNA cellulose and analyzed by Western blotting. Relative DNA-PKcs levels in extracts (E) compared to those in DNA-cellulose pulldowns (P) are depicted. (E) DNA-PK enzymatic levels were determined in extracts from V3 transfectants expressing wild-type DNA-PKcs, the N>Asp mutant, or vector control using a modification of the method described by Finnie et al. (17). Relative activity is depicted as the fold increase over no peptide as described previously (22).

Phosphorylation of JK inhibits NHEJ and promotes HR but does not affect enzymatic activity.

T946-Q947 (“J”) and S1004-Q1005 (“K”) are remarkably conserved (Fig. 5A). Each of these sites were studied as single S/T>Asp or S/T>Ala substitutions and as combined mutants. T946A, S1004A, and S1004D completely restored radioresistance to V3 cells (not shown). The T946D mutant only partially complemented the V3 radiosensitive phenotype (Fig. 5C). Whereas the combined JK>Ala mutant did not completely reverse the V3 radiosensitive phenotype, the combined JK>Asp mutant did not complement V3 radiosensitivity whatsoever. These data are reminiscent of data demonstrating that the ABCDE and PQR sites function as clusters. There is an additional completely conserved T-hyd residue in this region (T1007). This site was also replaced by alanine in the JK>Ala mutant; however, the phenotype in cells expressing this mutant was no different than that of the original JK>Ala mutant (not shown).

Cells expressing the JK>Ala mutant were fully competent in supporting both coding and signal end joining in transient VDJ assays; however, cells expressing the JK>Asp mutant were severely defective in both of these (data not shown). Sequence analysis of coding and signal joints mediated by the combined JK>Asp mutants revealed similar end processing, as observed with wild-type DNA-PKcs. Thus, unlike phosphorylations of the ABCDE and PQR sites, phosphorylation of the putative JK sites does not alter end processing.

A phospho-specific reagent was developed to detect phosphorylation of T946, the J site (Fig. 5E). Although this reagent detected phosphorylation of the J site in vitro, detection of damage-induced T946 phosphorylation with this reagent was not consistent (although phosphorylation could be detected in human cells in response to zeocin in ∼50% of the assays performed [not shown]). However, from these data and the mutagenesis data, we tentatively conclude that the J site (S946) is an authentic phosphorylation target and that phosphorylation of the JK sites may negatively regulate NHEJ. We next tried to ascertain the mechanistic basis for failed NHEJ in cells expressing the JK mutants. Briefly, neither phosphoblocking nor phosphomimicking JK substitutions affect the DNA-PKcs association with Ku-bound DNA (Fig. 5B), DNA-PK enzymatic activity (Fig. 5D), DNA-PK interaction with XRCC4 or Artemis (not shown), or appropriately targeting DNA-PK to a Triton-insoluble fraction in response to DNA damage (not shown). However, like the T3950 site, the phosphomimicking and phosphoblocking JK mutants have quite different effects on HR (Fig. 3C). Whereas the JK>Ala mutant (which has a mild NHEJ deficit) inhibits HR slightly better than wild-type DNA-PKcs, the JK>Asp mutant allows for substantially more HR. Because the JK>Asp mutant has a substantial NHEJ defect, the increased level of HR observed may be a reflection of failed NHEJ. Still, as with T3950 phosphorylation, JK phosphorylation might provide a mechanism for DNA-PK to disengage NHEJ and allow HR access to DNA damage. Again, it is tempting to speculate that increased radiosensitivity of cells that cannot phosphorylate the JK sites might be the result of an impaired ability to engage the HR pathway.

Phosphorylation of N inhibits NHEJ and HR and markedly impairs enzymatic activity.

S-hyd S56-57 (N-terminal site 1 [N1]) and S-hyd S72-73 (N2) are the most highly conserved of the potential sites targeted by this approach (Fig. 6A). N1 (S56) is present in every species (from humans to slime mold), and the N2 target (S72) is also present in every species, although the adjacent hydrophobic site is not conserved in slime mold. Moreover, phosphorylation of S72 was observed in the mass spectrometry screen of DNA-PKcs autophosphorylated in vitro (Yu and Lees-Miller, unpublished). These sites were studied as combined S/T>Asp or S/T>Ala mutants. Although the combined N>Ala mutant completely restores radioresistance to V3 cells, the N>Asp mutant fails to complement the V3 radiosensitive phenotype (Fig. 6B). VDJ recombination assays showed similar levels of impairment for each of these mutants, i.e., normal signal and coding end joining in cells expressing the N>Ala mutant but severe defects in both signal and coding end joining in cells expressing the N>Asp mutant (not shown). Sequence analysis of rare coding and signal joints mediated by the N>Asp mutants revealed similar end processing, as observed with wild-type DNA-PKcs. Thus, unlike phosphorylations of the ABCDE and PQR sites, phosphorylation of the putative N sites does not alter end processing.

A phospho-specific reagent was developed to detect phosphorylation of S72, the N2 site. Although S72 phosphorylation could not be consistently detected in V3 DNA-PKcs transfectants, S72 phosphorylation was consistently detected in human HCT116 cells in response to zeocin and mitomycin C (in the presence of okadaic acid) (Fig. 6C). This phosphorylation is not apparent in HCT116 cells that lack DNA-PKcs because of a targeted deletion (developed by Ruis and colleagues [34]). Although the V3 transfectants express 5- to 10-fold more DNA-PKcs than wild-type hamster cells, this is still about 5-fold less than that expressed by cultured human cells and likely explains our inability to detect S72 phosphorylation in V3 transfectants. From these data, we conclude that S72 (N2) is an authentic phosphorylation target, and from the mutagenesis data, we conclude that phosphorylation of the N sites may negatively regulate NHEJ.

Although the N>D substitution did not affect DNA-PKcs association with Ku-bound DNA (Fig. 6D), DNA-PK's enzymatic activity was remarkably reduced by this mutation (Fig. 6E). This is the first mutation in DNA-PK outside the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) domain or extreme C terminus that affects enzymatic activity. As discussed above, we have previously shown that DNA-PKcs with a 426-residue N-terminal deletion cannot complex with Ku bound to DNA. The extreme phenotype observed by phosphomimicking these highly conserved “N” sites is consistent with a model whereby N phosphorylation interferes with the interaction of DNA-PKcs with DNA, abrogating kinase activation. Still, the N>Asp mutant assembles appropriately onto DNA ends (Fig. 6D). Thus, if N phosphorylation contributes to kinase dissociation, this must occur in association with additional phosphorylation events. Given the phenotype of slow dissociation by the ABCDE>Ala mutant, it is intriguing to speculate that phosphorylations at both ABCDE and N are required to cause kinase dissociation. This model is currently under investigation.

The conclusion that the N>Asp mutant assembles onto Ku-bound DNA complexes in living cells is substantiated by the fact that the N>Asp mutant robustly inhibits HR (Fig. 3C), even though NHEJ is also severely impaired (Fig. 6B). A combined mutant ablating kinase activity in the phosphomimicking mutant (N>Asp/K3752R) does not inhibit HR (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that a DNA-PK phosphorylation event is required to restrict HR, and even the minimal catalytic activity of the N>Asp mutant is sufficient to mediate this phosphorylation.

DNA-PK-dependent phosphorylation of Ku, Artemis, or XRCC4 does not affect the relative level of HR.

We next considered that phosphorylation of another NHEJ factor might be necessary to restrict HR. We have previously characterized DNA-PK phosphorylation sites in Ku70, Ku86, XRCC4 (15, 42), and Artemis (19) (K. Meek, unpublished data). Although these phosphorylation events occur in living cells in response to DNA damage, none are required to restore radioresistance in cells lacking Ku, XRCC4, or Artemis; using similar strategies, we tested whether phosphoblocking or -mimicking mutants of other NJEJ factors affect HR. In sum, we find no evidence that DNA-PK phosphorylation of XRCC4, Ku70, Ku86, or Artemis affects the rate of HR (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Similar experiments were performed with 53BP1 and RPA32, both known to be targets of DNA-PK enzymatic activity. We found no evidence that DNA-PK phosphorylation of 53BP1 or RPA32 results in inhibition of HR (see Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

The fact that DNA-PK's enzymatic activity is required to inhibit HR may reflect the necessity to establish a functional NHEJ complex.

Using both chemical and mutational approaches, we found that DNA-PK's catalytic activity is absolutely required for its ability to inhibit HR. Although this conclusion contradicts a previous report (1), we provide several reasonable explanations for the discrepancies between their data using chemical inhibitors and the results presented here. Even more, data presented here are largely consistent with a more recent report from the same authors (37) (although perhaps not with their interpretations). Finally, during revision of the manuscript, another report substantiated our finding that chemical inhibition of DNA-PK enhances HR (11). In sum, these data are most consistent with the conclusion that enzymatically inactive DNA-PK cannot inhibit HR. In large part, this strict requirement for DNA-PK catalytic activity can be explained simply by a failure of NHEJ; failure of NHEJ provides more DNA ends for HR to repair. However, this presents another, still unanswered question: how are kinase-inactive DNA-PK complexes eliminated from sites of damage? A reasonable hypothesis is that another kinase (perhaps ATM or ATR) phosphorylates sites within DNA-PKcs, inducing complex dissociation. Although this is still a reasonable hypothesis, combined mutational experiments (combining kinase-inactivating mutations with phosphorylation-blocking mutations) eliminate several potential target sites within DNA-PKcs (ABCDE, PQR, JK, and S3205), including sites hypothesized (by others; ABCDE) to be phosphorylated by ATM. Another, not mutually exclusive hypothesis is that a DNA-PK phosphorylation event is required to establish a functional NHEJ complex in living cells and that without this initiating phosphorylation event, association of NHEJ components at a DSB is only transient. If this “functional NHEJ complex” includes DNA-PK and the downstream ligase complex, this would explain why HR is elevated in cells deficient in XRCC4 or ligase IV (32). Consistent with the idea that a functional NHEJ complex is required to impede HR, increased DNA-PKcs expression does not inhibit HR of the CFP substrate in the XRCC4-deficient XR-1 reporter cell strain (data not shown).

DNA-PK-mediated phosphorylations and phosphorylations of DNA-PK are functionally complex.

We have previously studied 13 phosphorylation sites in DNA-PKcs and reported that a mutant ablating all of these sites (by alanine substitution) still undergoes autophosphorylation-mediated kinase dissociation, suggesting that additional phosphorylation sites are functionally important. Indeed, recent reports document that numerous additional serines and threonines within DNA-PKcs are phosphorylated in living cells (reviewed in reference 13). Here, we study an additional seven sites (targeted because of their strong conservation and location in the molecule), bringing the total number of phosphorylation sites studied by mutagenesis to twenty. Mutants of four of the seven putative phosphorylation sites impart strong cellular phenotypes, and phospho-specific reagents document that these sites are actual targets, suggesting that these sites are both authentic and functionally relevant. Still, more work must be done to clarify what types of damage induce these phosphorylations and what kinase mediates the modifications.

Previous work with the ABCDE and PQR mutants using a neo HR cassette suggested that phosphorylation at these two clusters reciprocally regulated HR levels, which is similar to how these clusters function to regulate end processing during NHEJ (10). Technical difficulties with that assay (defined here) bring those data into question, and the results from the CFP-based HR assay do not support the previous conclusion. However, a limitation of the CFP-based HR assay is that accumulated HR is measured over many days. These data show that blocking ABCDE phosphorylation cannot block pursuant HR over a long time period, probably since the ABCDE mutant is fully capable of undergoing autophosphorylation-induced dissociation, albeit with slightly lower kinetics. Failure of NHEJ in cells expressing ABCDE eventually allows HR. NHEJ has rapid kinetics (within 30 min), whereas HR displays much lower kinetics (many hours) (26). Although it is possible that blocking ABCDE phosphorylation may initially slow HR, this inhibition may not be appreciated over the course of these relatively long HR assays (since the mutant kinase still undergoes autophosphorylation-induced kinase dissociation), an inherent limitation of HR reporter assays. In fact, Shibata and colleagues have shown suppressed 3′-end resection (assessed by RAD51 foci) in ABCDE>Ala-expressing (but not ABCDE>Asp-expressing) cells, specifically in G2 at the subset of DSBs that undergo resection. However, this reduction lasts only several hours (35a). These data are consistent with our observation of hyperradiosensitivity in cells expressing ABCDE>Ala but not ABCDE>Asp and suggest that the ABCDE>Ala mutant may exert a dominant negative effect over other pathways immediately after damage but not a sustained dominant negative effect.

DNA-PKcs is an authentic ATM substrate in living cells.

Phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs by ATM or ATR (at the ABCDE cluster) is controversial (6, 29, 39). Here, we document damage-induced phosphorylation of S3205 (“M”), in agreement with earlier genome-wide screens by Bennetzen et al. (3) and others (reviewed in reference 13), and ATM-dependent phosphorylation of S3205 (“M”), in agreement with Bensimon et al. (4). Although the S3205 mutation does not impart a strong cellular phenotype, the phospho-specific reagent developed for this site provides compelling evidence that DNA-PKcs is an authentic in vivo target of ATM. Although ATM phosphorylation of S3205 is not essential for either NHEJ or HR, these data document interplay between the two kinases and present a challenge to determine if and how the two enzymes might affect each other's function.

Definition of two phosphorylation sites at the extreme N terminus that impede kinase activation.

We have previously shown that DNA-PKcs with an N-terminal 426-amino-acid truncation cannot associate with Ku-DNA complexes, implicating DNA-PKcs's extreme N terminus in complex formation. Two highly conserved S-hyd potential phosphorylation sites are present at the extreme N terminus. S72 (N2) is phosphorylated both in vitro and in living cells, and a phosphomimicking mutant of the N sites ablates NHEJ because of severely reduced kinase inactivation. These data are consistent with a role for phosphorylation of these sites at the extreme N terminus in kinase inactivation and are consistent with emerging data from our laboratory documenting an important role for the N terminus in “sensing” DNA.

The N>Asp mutant robustly inhibits HR, even though NHEJ is also severely impaired, demonstrating that failed NHEJ does not always result in increased HR. A combined mutant ablating kinase activity in the phosphomimicking mutant (N>Asp/K3952R) does not inhibit HR. Together, these data suggest that a DNA-PK phosphorylation event is required to restrict HR and that the DSBR pathway choice is actively regulated and not just the consequence of a competition between pathways. The definition of the targeted site is the focus of ongoing investigation.

JK and T3950 phosphorylation provide a mechanism for NHEJ disengagement.

Given the very high expression levels of Ku and DNA-PKcs, an important question at the outset of these experiments was that if the DSBR pathway choice is just a competition, how does a cell ensure that DNA-PK does not always win. This is of critical importance to the cell because there are some DNA ends that should be protected from NHEJ, for instance, single double-strand ends that result from replication fork collapse. In fact, elegant work by Arlt and colleagues described remarkably frequent genomic deletions in human cells undergoing replication stress (2). These deletions were likely mediated by NHEJ of single DNA ends from different stalled replication forks. These data are consistent with earlier studies documenting the presence of autophosphorylated DNA-PKcs at stalled replication forks in similarly replication-stressed cultured human cells (35). Here we describe three DNA-PKcs phosphorylations (JK sites and T3950) that inhibit NHEJ while promoting HR. We suggest that phosphorylation of either the JK sites or T3950 (in the putative activation loop) provides an efficient mechanism to protect certain ends from the NHEJ pathway. Blocking phosphorylation of these sites results in moderate radiosensitivity, suggesting that the capacity to disengage NHEJ is functionally relevant to cellular survival after ionizing radiation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank to Ruiqiong Ye and Yao Xu for excellent technical assistance, Yaping Yu (Lees-Miller laboratory) and Rulin Zhang (WEMB Inc., Toronto, Canada) for mass spectrometry analysis of in vitro DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation sites, Jane Leitch and Diagnostics Scotland for making the phospho-specific antibody to serine 3205, and S. Elledge and P. Jeggo for sharing unpublished observations and for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI048758 (to K.M.) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant 13639 (to S.P.L.-M.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 7 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen C., Halbrook J., Nickoloff J. A. 2003. Interactive competition between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining. Mol. Cancer Res. 1:913–920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arlt M. F., et al. 2009. Replication stress induces genome-wide copy number changes in human cells that resemble polymorphic and pathogenic variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84:339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennetzen M. V., et al. 2010. Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics of the nuclear proteome during the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9:1314–1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bensimon A., et al. 2010. ATM-dependent andindependent dynamics of the nuclear phosphoproteome after DNA damage. Sci. Signal. 3:rs3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Block W. D., et al. 2004. Autophosphorylation-dependent remodeling of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit regulates ligation of DNA ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:4351–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen B. P., et al. 2007. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is essential for DNA-PKcs phosphorylations at the Thr-2609 cluster upon DNA double strand break. J. Biol. Chem. 282:6582–6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Convery E., et al. 2005. Inhibition of homologous recombination by variants of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corneo B., et al. 2007. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature 449:483–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui X., Meek K. 2007. Linking double-stranded DNA breaks to the recombination activating gene complex directs repair to the nonhomologous end-joining pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17046–17051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cui X., et al. 2005. Autophosphorylation of DNA-dependent protein kinase regulates DNA end processing and may also alter double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:10842–10852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davidson D., et al. 11 January 2011. Irinotecan and DNA-PKcs inhibitors synergize in killing of colon cancer cells. Invest. New Drugs [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1007/s10637-010-9626-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ding Q., et al. 2003. Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase is required for efficient end processing during DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5836–5848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dobbs T. A., Tainer J. A., Lees-Miller S. P. 2010. A structural model for regulation of NHEJ by DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation. DNA Repair (Amst.) 9:1307–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Douglas P., et al. 2007. The DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit is phosphorylated in vivo on threonine 3950, a highly conserved amino acid in the protein kinase domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:1581–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Douglas P., Gupta S., Morrice N., Meek K., Lees-Miller S. P. 2005. DNA-PK-dependent phosphorylation of Ku70/80 is not required for non-homologous end joining. DNA Repair (Amst.) 4:1006–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Douglas P., et al. 2002. Identification of in vitro and in vivo phosphorylation sites in the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase. Biochem. J. 368:243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finnie N. J., Gottlieb T. M., Blunt T., Jeggo P. A., Jackson S. P. 1995. DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is absent in xrs-6 cells: implications for site-specific recombination and DNA double-strand break repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:320–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Getts R. C., Stamato T. D. 1994. Absence of a Ku-like DNA end binding activity in the xrs double-strand DNA repair-deficient mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 269:15981–15984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodarzi A. A., et al. 2006. DNA-PK autophosphorylation facilitates Artemis endonuclease activity. EMBO J. 25:3880–3889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gupta S., Meek K. 2005. The leucine rich region of DNA-PKcs contributes to its innate DNA affinity. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:6972–6981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haring S. J., Humphreys T. D., Wold M. S. 2010. A naturally occurring human RPA subunit homolog does not support DNA replication or cell-cycle progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:846–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kienker L. J., Shin E. K., Meek K. 2000. Both V(D)J recombination and radioresistance require DNA-PK kinase activity, though minimal levels suffice for V(D)J recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2752–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kurimasa A., et al. 1999. Requirement for the kinase activity of human DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in DNA strand break rejoining. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3877–3884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee G. S., Neiditch M. B., Salus S. S., Roth D. B. 2004. RAG proteins shepherd double-strand breaks to a specific pathway, suppressing error-prone repair, but RAG nicking initiates homologous recombination. Cell 117:171–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahaney B. L., Meek K., Lees-Miller S. P. 2009. Repair of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks by non-homologous end-joining. Biochem. J. 417:639–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mao Z., Bozzella M., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V. 2008. Comparison of nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination in human cells. DNA Repair (Amst.) 7:1765–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mao Z., Bozzella M., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V. 2008. DNA repair by nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination during cell cycle in human cells. Cell Cycle 7:2902–2906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meek K., Dang V., Lees-Miller S. P. 2008. DNA-PK: the means to justify the ends? Adv. Immunol. 99:33–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meek K., Douglas P., Cui X., Ding Q., Lees-Miller S. P. 2007. trans autophosphorylation at DNA-dependent protein kinase's two major autophosphorylation site clusters facilitates end processing but not end joining. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:3881–3890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morales J. C., et al. 2003. Role for the BRCA1 C-terminal repeats (BRCT) protein 53BP1 in maintaining genomic stability. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14971–14977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng Y., et al. 2005. Deficiency in the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase causes down-regulation of ATM. Cancer Res. 65:1670–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pierce A. J., Hu P., Han M., Ellis N., Jasin M. 2001. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 15:3237–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]