Abstract

Bile acid resistance by Lactococcus lactis depends on the ABC-type multidrug transporter LmrCD. Upon deletion of the lmrCD genes, cells can reacquire bile acid resistance upon prolonged exposure to cholate, yielding the ΔlmrCDr strain. The resistance mechanism in this strain is non-transporter based. Instead, cells show a high tendency to flocculate, suggesting cell surface alterations. Contact angle measurements demonstrate that the ΔlmrCDr cells are equipped with an increased cell surface hydrophilicity compared to those of the parental and wild-type strains, while the surface hydrophilicity is reduced in the presence of cholate. ΔlmrCDr cells are poor in biofilm formation on a hydrophobic polystyrene surface, but in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of cholate, biofilm formation is strongly stimulated. Biofilm cells show an enhanced extracellular polymeric substance production and are highly resistant to bile acids. These data suggest that non-transporter-based cholate resistance in L. lactis is due to alterations in the cell surface that stimulate cells to form resistant biofilms.

INTRODUCTION

Lactococcus lactis, like other lactic acid bacteria, survives, albeit weakly, in the human gastrointestinal tract (23). Importantly, bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract need to be resistant to bile salts. When they successfully colonize such a niche, they must transit from a planktonic phase to a biofilm phase. A biofilm community is classically characterized by a sessile mode of existence, in which cells are encased in a secreted extracellular matrix while attached or exposed to a surface (21). However, the condition of surface attachment is flexible, since free-floating flocs with minimal surface attachment are also regarded as biofilms (24). Bacteria growing in biofilms exhibit a specific phenotype and are often but not always more resistant (38) to antimicrobial agents than their planktonic counterparts. Such enhanced resistance appears to be caused by numerous mechanisms (14). Several studies have implicated efflux pumps in the antimicrobial resistance of biofilms (14, 25). Although in Gram-positive bacteria ABC-type drug transporters are known to contribute to drug resistance of planktonic cells (25), so far none have been implicated in biofilm-specific antimicrobial resistance. A recent report suggests the involvement of a putative ABC transporter in biofilm-specific resistance in Gram-negative bacteria (42).

The ABC-type multidrug resistance (MDR) transporter LmrCD is a major determinant of drug resistance in L. lactis, but it is also involved in bile acid resistance (41). Consequently, L. lactis cells that lack the lmrCD genes are sensitive to bile acids, such as cholate. When these cells are exposed to stepwise-increasing sublethal concentrations of cholate, they develop an improved resistance to cholate and several other bile acids (41). The resultant strain was termed the L. lactis ΔlmrCDr strain. Transcriptome and functional analysis suggests that the resistance by this strain is no longer transporter based but is due to cell envelope- and metabolism-related alterations (41). These cells show a decreased growth rate and an increased ability to flocculate, but it is unclear how they perform in biofilms. Biofilm development is a complex multistep process, and both its initiation and consolidation are greatly influenced by environmental stresses, such as bile acids (3).

Here we have investigated the surface and biofilm-forming properties of three different strains of L. lactis: (i) the wild type, (ii) the ΔlmrCD strain, which lacks the major multidrug transporter LmrCD (27), and (iii) the ΔlmrCDr strain, a cholate-resistant strain derived from the L. lactis ΔlmrCD strain (41). The data indicate a cholate-dependent physicochemical alteration of the ΔlmrCDr cell surface and the development of biofilms with a distinctly different matrix structure and composition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

L. lactis NZ9000 is a derivative of the plasmid-free L. lactis MG1363 strain containing pepN::nisRK (11, 12), referred to as the wild type. L. lactis NZ9000 ΔlmrCD (28) and its cholate-resistant derivative, the ΔlmrCDr strain (41), lack the ABC-type MDR transporter LmrCD. Cells were grown in M17 medium (Difco) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17) at 30°C. Growth in microtiter plates was monitored by absorbance using a multiscan photometer at specified wavelengths (spectraMax 340; Molecular Devices).

Biofilm formation.

The ability of L. lactis to form biofilms was assessed by a previously described method with minor modifications (7). Cells were grown for 24 h in GM17 and subsequently diluted to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 1 in fresh GM17 supplemented with selected drugs and detergents at various concentrations. Next, aliquots of 200 μl were transferred into the wells of a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate. For each drug concentration, 7 wells were used. Plates were then sealed with Parafilm and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Planktonic cells were transferred to a new microtiter plate, and the OD660 was measured. For each drug concentration, the biofilm of a single well was thoroughly scraped from the walls of the well using a pipette tip and cells were resuspended in 200 μl of fresh GM17. The OD660 was used as a measure of the biofilm cell density. The biofilms in the remaining wells were washed twice by fully submerging the plate in deionized water, air dried overnight, stained for 15 min with an aqueous solution of 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet, rinsed with water, and air dried overnight. The crystal violet-stained biofilm was suspended to homogeneity in 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the OD575 was measured for each of the wells and averaged. Wells containing sterile GM17 served as controls and were used for background subtraction. To relate biofilm formation to cell density, the ratio of biofilm OD575 to OD660 was calculated. Assays were repeated three times with independent cultures.

Growth inhibition bioassays.

Growth inhibitions assays were performed with different types of cells that when appropriate were pregrown in the absence or presence of 1.5 mM cholate. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data shown are averaged with indicated standard errors of the means.

(i) Planktonic cells.

Overnight cultures of the indicated L. lactis strains were diluted in fresh GM17 and grown to an OD660 of 0.6. Aliquots of 150 μl were transferred to 96-well microtiter plates that contained 50 μl of GM17 medium and, when needed, drugs at a given concentration. Plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated for 12 h, after which the OD660 was measured. Concentrations that inhibited growth by 50% (IC50) and 100% (MIC) were determined.

(ii) Biofilm cells.

The drug, EDTA, and bacitracin susceptibilities of L. lactis biofilms were determined as described previously (17) with minor modifications. Cells grown for 12 h in GM17 were diluted in fresh GM17 without or with 1.5 mM cholate to an OD660 of 0.6. Aliquots of 200 μl were transferred to each well of a 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate covered with a 96-peg lid of polystyrene (Nunc, Denmark). Cells were incubated for 24 h to allow biofilm formation on the pegs. To remove nonadherent cells, the peg lid was dipped into a series of three 96-well plates containing 200 μl of sterile 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.0, per well. The peg lid was then placed on a fresh plate that contained in each well 200 μl GM17 with the appropriate drug. GM17 medium without drugs served as a positive growth control. Biofilms were incubated overnight at 30°C, rinsed three times in PBS as described above, and placed in a final 96-well plate containing 200 μl of GM17. Biofilm cells were then dislodged from the pegs by bath sonication of the microtiter plate for 5 min at 40 kHz (Zenith Ultrasonics, Norwood, NJ). The peg lid was removed, and the OD660 of the remaining suspension in the wells was determined (0 h). The plate was covered by a normal lid and incubated for 24 h, after which a second OD660 reading was taken. The IC50 was defined as the drug concentration that showed 50% growth reduction compared to the growth in control wells with no drugs. Wells containing sterile GM17 served as spectrophotometric blanks.

(iii) Biofilm-derived cells.

Biofilms were grown essentially as described above. After washing in PBS, cells associated with the biofilms were removed from the pegs by sonication directly in microplate wells and suspended in GM17 containing different concentrations of the drugs. Following a 12-h incubation in the presence of the drug, the OD660 was measured.

Determination of CFU.

Biofilms of L. lactis were prepared as described above in 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates, in which GM17 growth medium was supplemented with 0, 1.5, or 3 mM sodium cholate from a 500 mM stock solution. After 24 h of growth, the planktonic cells were pooled from eight wells per strain for each condition tested. CFU were determined by serial dilution and plating on M17 plates that were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. Biofilm cell populations were determined by adding fresh PBS to the wells of the plate from which the planktonic cells were removed. Cells were detached from the walls with a sterile pipette tip, pooled from three wells, and dispersed by bath sonication for 5 min at 40 kHz (Zenith Ultrasonics, Norwood, NJ). Microscopic inspection of the cells confirmed that the biofilms were dispersed by the treatment. Serial dilutions of the cells were plated on M17 agar, and the number of CFU was determined after growth for 24 h at 30°C. The sonication time was optimized in order to detach the maximum number of adhered cells without cell disruption (assessed by plating the final suspension on GM17 plates).

Contact angle measurements.

For cell surface hydrophobicity measurements, contact angles were determined using cells harvested at mid-exponential growth phase. Cells were washed twice with 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, and suspended in the same buffer at an OD660 of 0.5. Cells (10 ml) were transferred to cellulose acetate membrane filters (pore size, 0.22 nm; Osmonics) to produce an even bacterial lawn. The sheets were washed with Nanopure water and air dried for 30 to 40 min until so-called “plateau contact angles” could be measured using water droplets. Droplets of four liquids (water, formamide, α-bromonaphthalene, and diiodomethane) were applied to each bacterial lawn (using Teflon/glass syringes equipped with 24-gauge stainless steel Luer-tipped hypodermic needles; Gilmont Instruments). The contact angle of the droplet on the bacterial lawn was monitored with an optical microscope equipped with a charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera. For static contact angles, the droplet was allowed to settle for 2 s without needle contact. The mean contact angles for each biological sample were calculated from five droplets, measured on different areas of the membrane surface. The total surface free energies (SFE) and the polar and nonpolar contribution to the total SFE were determined from contact angle measurements as described previously (6). The Van Oss equation was used to calculate the dispersive (γLW) and polar acid/base (γAB) components, with the latter subdivided into an acidic (γ+) and a basic (γ−) term. Mean values were calculated. Based on these parameters, the free energy of adhesion to polystyrene was also calculated.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was used to visualize biofilms as described before (30). Biofilms were grown in 24-well tissue culture polystyrene plates in the presence of 1.5 to 3 mM sodium cholate and 24 to 48 mM sodium taurocholate for 24 h, washed with PBS, and stained with the bacterial Live/Dead stain BacLight (Invitrogen) for 30 min in the dark. Excess stain was removed, and the biofilms were submerged in 2 ml PBS. Images were collected using a Leica TCS SP2 CLSM with a 40× water objective using 488-nm excitation and 500- to 523-nm (green, alive) and 622- to 722-nm (red, dead) emission filter settings. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) were stained using calcofluor (Sigma).

RESULTS

Cell surface properties of bile acid-resistant L. lactis.

The multidrug transporter LmrCD of L. lactis contributes to bile acid resistance (27). When the lmrCD genes are deleted from the chromosome, cells can regain bile acid resistance when challenged for a prolonged time with increasing concentrations of cholate. The cholate resistance in this strain, which is termed the ΔlmrCDr strain, is not transporter based. Transcriptome analysis suggests a high incidence of genes involved in cell envelope biogenesis that are up- and downregulated (41). To determine if the ΔlmrCDr strain is equipped with an altered cell envelope, we analyzed the global physicochemical properties of the cell surface. For this purpose, contact angle measurements were performed on bacterial lawns, partly dehydrated cells. Surface free energies were calculated from the contact angle measurements in the absence and presence of cholate, which is a measure of the hydrophilicity of the cell surface (Table 1). In the analysis, three strains were compared, i.e., the wild-type strain, the derivative that lacks the LmrCD transporter (ΔlmrCD), and the cholate-adapted ΔlmrCDr strain. In the absence of cholate, the surfaces of all three strains are predictably hydrophilic (19), with water contact angles (θW) in the range of 18° to 29°. However, with exposure to cholate, the contact angle of the ΔlmrCDr strain of 1-bromonaphthalene (θB) and formamide (θF) decreased, indicating that the cells became more hydrophilic. On the other hand, the parental and wild-type strains showed similar contact angles in the presence and absence of cholate. For the ΔlmrCDr strain, exposure to cholate resulted in an increase of the Lifshitz-Van der Waals component, γLW, from 37.7 to 39.3 mJ·m−2, while the Lewis acid-base component, γAB, increased from 13.2 to 16.5 mJ·m−2. This resulted in an overall negative value for the interfacial free energy of adhesion, ΔGadh (Table 2), to polystyrene for the ΔlmrCDr strain. The analysis of the polar component of the surface free energy shows that unlike the parental and wild-type cells, ΔlmrCDr cells show pronounced changes in both the acidic (or electron acceptor) component (γ+) and basic (or electron donor) component (γ−) upon exposure to cholate. This implies that the alteration in the cell surface polarity relates to cholate-dependent changes in the acid-base nature of the cell surface, with only a minor role of the apolar Lifshitz-Van der Waals forces. With the wild-type cells, we noted an increase in the basic component (γ−) upon exposure to cholate, resulting in a slightly positive ΔGadh and thus a slightly increased hydrophilicity. Overall, these data demonstrate the cholate-dependent alterations in the cell surface properties of the ΔlmrCDr cells, rendering these cells more hydrophilic.

Table 1.

Contact angle and surface free energy components of L. lactis ΔlmrCDr, ΔlmrCD, and wild-type cells with and without exposure to cholate

| Condition and strain description | Contact angle (°)a |

Parameter value (mJ m−2)b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θW | θF | θB | θD | γLW | γ− | γ+ | γAB | γtotal | |

| Without cholatec | |||||||||

| ΔlmrCDr | 18 ± 3 | 25 ± 3.2 | 32 ± 3 | 44 ± 3 | 37.7 | 56.4 | 0.8 | 13.4 | 50.9 |

| ΔlmrCD | 29 ± 1.8 | 26 ± 2.6 | 29 ± 4.8 | 47 ± 2.5 | 37.2 | 46.9 | 1.1 | 13.2 | 51.6 |

| Wild type | 29 ± 0.5 | 28 ± 1.0 | 32 ± 0.6 | 49 ± 7.2 | 36.3 | 48.2 | 1.1 | 14.3 | 50.7 |

| With cholatec | |||||||||

| ΔlmrCDr | 22 ± 3.2 | 14 ± 1.2 | 24 ± 1.0 | 43 ± 0.6 | 39.3 | 47.8 | 1.4 | 16.5 | 55.8 |

| ΔlmrCD | 30 ± 2.9 | 29 ± 1.5 | 30 ± 2.4 | 51 ± 1.8 | 36.3 | 47.4 | 1.0 | 13.7 | 50.0 |

| Wild type | 24 ± 1.5 | 29 ± 1.5 | 28 ± 4.9 | 52 ± 0.8 | 36.3 | 53.5 | 0.8 | 13.1 | 49.3 |

θW, θF, θB, and θD, contact angles of water, formamide, 1-bromonaphthalene, and diiodomethane, respectively.

γLW, Lifshitz-Van der Waals component of interfacial tension; γ−, γ+, electron donor, and electron acceptor components of interfacial tension; γAB, Lewis acid-base component of interfacial tension; γtotal, total surface tension, which is the additive sum of γLW and γAB. The most pronounced changes in comparing cholate-exposed and control cells are highlighted in boldface.

Cells were grown tol stationary phase in GM17 in the presence or absence of 1.5 mM Na-cholate.

Table 2.

Interfacial free energy of adhesion between polystyrene surface and L. lactis cells with and without exposure to cholate

| Condition | Strain description | Interfacial free energy of adhesion, ΔGadh (mJ m−2)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGadhLW | ΔGadhAB | ΔGadhtotalb | ||

| Without cholate | ΔlmrCDr | −5.1 | 7.9 | 2.7 |

| ΔlmrCD | −5.0 | 1.8 | −3.2 | |

| Wild type | −4.7 | 2.8 | −2.0 | |

| With cholate | ΔlmrCDr | −5.6 | 3.1 | −2.6 |

| ΔlmrCD | −4.7 | 2.0 | 2.7 | |

| Wild type | −4.7 | 5.9 | 1.2 | |

Cells were grown till stationary phase in GM17 in the presence of 1.5 mM cholate.

The interaction with the surface is thermodynamically unfavorable when the total interfacial free energy of adhesion is positive. Surface free energy (in mJ m−2) values of polystyrene are as follows: γLW, 41.2; γAB, 0; γ+, 0; and γ−, 9.06 (used in the calculation of the ΔGadh values).

Enhanced biofilm formation by cholate-adapted L. lactis ΔlmrCD cells.

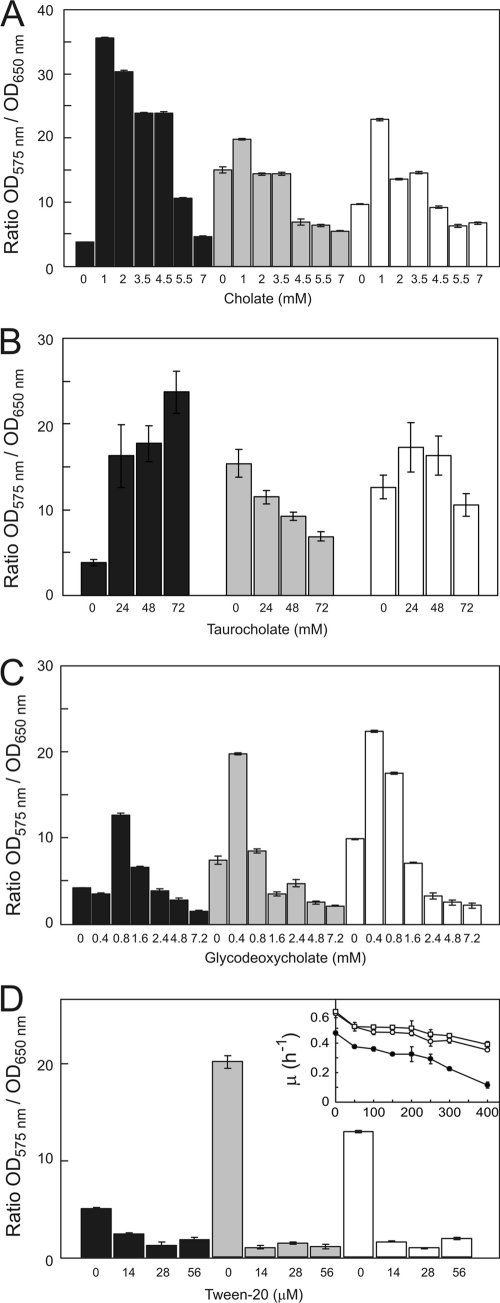

The cholate-adapted ΔlmrCDr cells show an enhanced flocculation phenotype in liquid medium compared to the parental strain (41) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Unlike the physicochemical changes in surface hydrophilicity, the flocculation phenotype was not influenced by the cholate exposure (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, we examined the effect of cholate on the ability of cells to form biofilms on various surfaces. Herein, we used a crystal violet-based microtiter plate assay. This stain binds to negatively charged molecules, such as peptidoglycan and DNA, and its absorption to cells therefore serves as a measure for biomass at the surface, i.e., biofilms (7). L. lactis was grown for 24 h in wells of polystyrene (hydrophobic) microtiter plates. Next, the planktonic cells were removed and the remaining wall-associated biofilms were stained with crystal violet and quantitated. In the absence of cholate, the cholate-adapted L. lactis ΔlmrCDr strain showed a considerably poorer ability to form biofilms than the wild-type and ΔlmrCD cells (Fig. 1A). When cells were exposed to subinhibitory concentrations of cholate, biofilm formation was stimulated for all three strains tested, but the effect was the most pronounced with the ΔlmrCDr strain (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the cholate-adapted ΔlmrCDr cells showed more biofilm formation on glass, and this was stimulated more strongly by cholate than on polystryrene surfaces (see Fig. S2). Higher cholate concentrations were inhibitory for growth, and consequently the biofilms were inhibited, although the ΔlmrCDr strain remained the most effective in biofilm formation even at higher cholate concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Biofilm formation by L. lactis wild-type (white bars), ΔlmrCD (gray bars), or cholate-adapted ΔlmrCDr (black bars) cells. Cultures were grown for 24 h in GM17 medium containing various concentrations of cholate (A), taurocholate (B), glycodeoxycholate (C), or Tween 20 (D) in 96-well microtiter plates. The OD660 of the resuspended biofilm was measured, and cells were stained with crystal violet, whereupon the OD575 was measured. Inset: Tween 20 resistance of L. lactis wild type (□), ΔlmrCD (○), and ΔlmrCDr (●) cells. Cells were grown for 8 h in GM17 medium in the absence or presence of various concentrations of Tween 20, and the maximum specific growth rate, μ, was determined. Data presented are averages of five replicates, and error bars represent calculated standard deviations.

To assess the specificity of the cholate-promoting effect on biofilm formation by the ΔlmrCDr strain, several other bile acids and detergents were tested. Unconjugated bile salts containing one or two hydroxyl groups, such as lithocholate, chenodeoxycholate, and deoxycholate, also stimulated biofilm formation. The steroidal anionic detergent 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) showed a weaker stimulatory effect, whereas dehydrocholate, a cholate molecule devoid of the three hydroxyl groups, did not affect biofilm formation (data not shown). The bile acid conjugate taurocholate had a strong effect on biofilm formation by the ΔlmrCDr strain (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, glycoconjugates, such as glycodeoxycholate (Fig. 1C) and glycocholate, showed an overall weak stimulatory effect. Nonionic detergents like Tween 20 (Fig. 1D), Triton X-100, and Brij58, the anionic detergents sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium lauroyl sulfate, and the cationic detergent benzalkonium chloride strongly inhibited biofilm formation at concentrations that only marginally inhibited growth of planktonic cells (for Tween 20, see the inset of Fig. 1D). These data demonstrate that the stimulatory effect of cholate on biofilm formation by the ΔlmrCDr strain is not due to a general detergent-like phenomenon but is specific for unconjugated or hydrophilic conjugated bile acids, in particular.

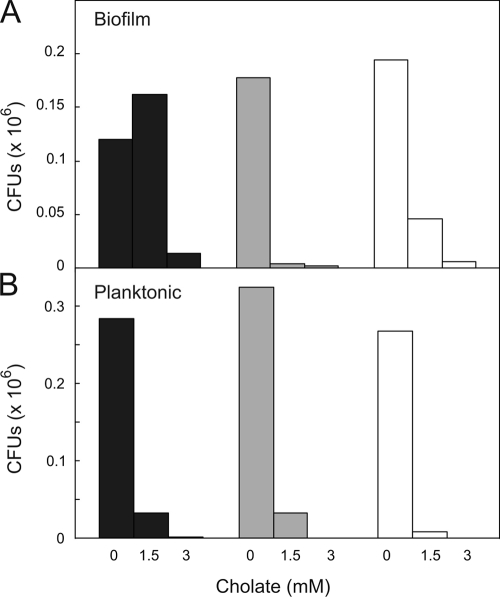

To distinguish between a stimulatory effect of cholate on the cell number and biofilm matrix, an independent assay was performed based on the viable cell count in biofilms. Herein, biofilms were dissolved in growth medium, followed by plating and assessment of the number of CFU. Since L. lactis cells grow in short chains, the plating method provides an underestimate of the number of viable cells. However, the chain length differences among the strains (41) could be minimized by sonication (data not shown). Biofilms formed in the absence of cholate showed no major differences in CFU for the wild-type and ΔlmrCD strains. However, much lower CFU numbers were found for the ΔlmrCDr strain (Fig. 2), consistent with the crystal violet staining data. Exposure to a cholate (1.5 mM) concentration that was inhibitory to the planktonic cells also resulted in lower CFU numbers for both the wild-type and ΔlmrCD cells extracted from the biofilms. However, the CFU for the ΔlmrCDr biofilms increased significantly (Fig. 2). Higher concentrations of cholate (3 mM) were inhibitory to biofilms of all cell types. These data demonstrate that cholate strongly stimulates biofilm formation by the ΔlmrCDr cells.

Fig. 2.

Planktonic and biofilm growth and cholate-induced killing monitored by CFU. Biofilm formation by L. lactis wild-type (open bars), ΔlmrCD (gray bars), and cholate-adapted ΔlmrCDr (black bars) cells is analyzed. Dilutions (10−2, 10−4, and 10−6) of the liquid culture and resuspended biofilms grown with or without 1.5 mM cholate were spread plated on GM17 agar plates without cholate and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The experiments were performed in duplicate; two independent experiments show a variation of less than 10%.

L. lactis biofilms exhibit an increased resistance to both bile acids and drugs.

Biofilm-associated cells typically exhibit an increased resistance to toxic compounds compared to planktonic cells (9). The increased resistance has been attributed to a variety of phenomena, including a reduced penetration of antimicrobials and the production of efflux pumps and enzymes for drug detoxification (36). Interestingly, upon cholate exposure, biofilms of the wild-type strain yielded higher CFU numbers than the ΔlmrCD strain (Fig. 2), suggesting that the MDR transporter LmrCD plays a role in biofilm survival. To examine this phenomenon in more detail, the bile acid and drug resistance profiles of the L. lactis wild type, ΔlmrCD strain, and ΔlmrCDr strain were compared. L. lactis biofilms were allowed to develop on a polystyrene surface, whereupon they were exposed to different toxic compounds for 18 h. Next, the biofilm cells were harvested and grown in liquid medium for 24 h. Growth was used as a general measure of survival. Likewise, planktonic cells were harvested from the liquid medium, serving as controls. Typically, the biofilm-associated cells showed a greater resistance to both conjugated and unconjugated bile acids than the planktonic cells. Even in the biofilm state, ΔlmrCD cells are more sensitive to cholate than wild-type cells, with IC50s of 2.3 and 7.4 mM, respectively (Table 3). The ΔlmrCDr biofilm cells showed a remarkably high resistance to cholate (IC50 > 14 mM), exceeding that of the wild-type cells. Compared to the planktonic cells, ΔlmrCDr biofilms exhibited a substantial increase in resistance to all conjugated and unconjugated bile acids tested (Table 3). L. lactis biofilms also exhibited an increased resistance to such toxic drugs as daunomycin, rhodamine 6G, and quinine and several none-bile detergents compared to results for the planktonic cells (Table 3). Interestingly, compared to the wild type, ΔlmrCD (and ΔlmrCDr) biofilm cells were more susceptible to the zwitterionic detergent CHAPS and the drugs daunomycin and quinine. CHAPS is the zwitterionic derivative (18) of cholate. These compounds are known substrates of LmrCD, indicating that LmrCD contributes to drug resistance of the biofilms.

Table 3.

Susceptibility of planktonic and preformed biofilm cells of L. lactis wild type, ΔlmrCD, and ΔlmrCDr strains to various bile acids, detergents, and drugs

| Treatment | IC50 (mM) of treatment agent for indicated strain with or without preexposure to cholatea |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planktonic |

Biofilm |

|||||||||||

| ΔlmrCDr |

ΔlmrCD |

Wild type |

ΔlmrCDr |

ΔlmrCD |

Wild type |

|||||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Bile acid | ||||||||||||

| Cholate | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | >14 | >14 | 2.3 | >14 | 7.4 | >14 |

| Deoxycholate | 0.63 | 0.5 | 0.58 | 0.5 | 0.58 | 0.6 | 1.15 | 2.1 | 1.18 | 0.3 | 1.22 | 1.0 |

| Chenodeoxycholate | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.12 | 2.23 | 1.02 | 0.26 | 1.15 | 0.94 |

| Lithocholate | 3.4 | >3.6 | >3.6 | >3.6 | >3.6 | >3.6 | 5.5 | >7.2 | >7.2 | >7.2 | >7.2 | >7.2 |

| Glycocholate | 23 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 |

| Taurocholate | 29 | 5 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 | >48 |

| Glycodeoxycholate | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.60 | 25 | 34 | 37.5 | >128 | >128 | 34 | >128 | >128 |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 2 | 6 | 51.5 | 63 | 72.5 | 80 | 114 | 114 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Dehydrocholate | 47 | 40 | 54 | 39 | >100 | 50 | >160 | >160 | >160 | >160 | >160 | >160 |

| Detergent | ||||||||||||

| CHAPS | 2.4 | 0.03 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 3 | 0.14 | 0.6 | 1.26 | 2.65 | 2.45 | >10 | 10 |

| Triton X-100 | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.02 | >1.5 | >1.5 | 0.03 | >1.5 | 0.06 |

| Benzalkonium-Cl | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| Sodium lauroyl sarcosin | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| SDS | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| Brij-58 | 0.01 | 0.01 | >20 | >20 | >20 | >20 | 22 | 1.3 | >100 | 9.5 | >100 | 16 |

| Drug | ||||||||||||

| Daunamycin | 0.0016 | 0.0015 | 0.0017 | 0.0018 | 0.049 | 0.088 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.089 | 0.083 |

| Rhodamine 6G | 0.0031 | 0.0051 | 0.0035 | 0.0052 | 0.0071 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.017 | >0.02 | >0.02 | >0.02 |

| Quinine | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 1.24 | 1.31 | 1.18 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

“+” and “−” indicate preexposure to cholate (1.5 mM) or the lack thereof. The most distinct change in biofilm cells of the ΔlmrCDr strain compared to the parental strain is highlighted in boldface.

Next, we determined whether preexposure to cholate affected the drug resistance of the cells. While the bile acid resistance phenotype of planktonic cells was barely altered by preexposure to cholate, cells present in the biofilms gained a large increase in resistance against cholate (Table 3). ΔlmrCDr cells were already resistant to the highest concentration of cholate tested. Upon preexposure to cholate, the ΔlmrCDr biofilms also showed an increased resistance to the conjugated bile acid glycodeoxycholate, the unconjugated bile acids deoxycholate, chenodeoxycholate, and lithocholate, and some detergents. In contrast, preexposure to cholate rendered wild-type and ΔlmrCD biofilms more sensitive to unconjugated bile acids and the detergents TX-100 and Brij-58 (Table 3). Cholate exposure did not alter the resistance of biofilms of wild-type cells toward drugs. Similarly, taurocholate, which promotes strong biofilm formation in ΔlmrCDr cells, does not improve the resistance to drugs like daunomycin (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In summary, these data demonstrate that biofilms of L. lactis are highly resistant to a range of bile acids and show that the resistance of ΔlmrCDr biofilms can be enhanced by preexposure of the cells to cholate. The enhancement of sessile cells is restricted to the biofilm phase since the cells that are dislodged from the biofilms behave similarly to the stationary-phase planktonic cells (see Table S1).

Role of LmrCD in drug resistance of L. lactis biofilms.

The role of LmrCD in biofilm resistance was further examined by providing L. lactis wild-type, ΔlmrCD, and ΔlmrCDr cells with a plasmid carrying the lmrCD genes under the control of the endogenous promoter (27). Cells carrying the empty vector served as controls. Both biofilm and planktonic cells harboring plasmid-encoded LmrCD were significantly more resistant to cholate and daunomycin than the control cells (Table 4). With ΔlmrCDr biofilm cells, which already have an intrinsically high resistance to cholate, expression of plasmid-encoded LmrCD resulted in a modest increase in cholate resistance, whereas wild-type and ΔlmrCD biofilms showed 5- and 8-fold increases in resistance to cholate, respectively (Table 4). Collectively, these results demonstrate that LmrCD provides cholate and drug resistance in the lactococcal biofilms. In addition, other mechanisms persist in the biofilms that render these structures highly resistant to toxic compounds.

Table 4.

Effect of lmrCD expression on cholate susceptibilities of planktonic and biofilm L. lactis cells

| Cell configuration | Strain description | Susceptibility to: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholate (IC50, mM) |

Daunomycin (IC50, μM) |

||||

| pILlmrCD | Empty vector | pILlmrCD | Empty vector | ||

| Planktonic | ΔlmrCDr | 4.7 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| ΔlmrCD | 4.1 | 2.1 | 49 | 2.7 | |

| Wild type | 4.1 | 2.6 | 52 | 24 | |

| Biofilm | ΔlmrCDr | 16 | 14.6 | 50.5 | 2.8 |

| ΔlmrCD | 18.2 | 2.4 | 39 | 3.2 | |

| Wild type | 22 | 4.1 | 49 | 19.5 | |

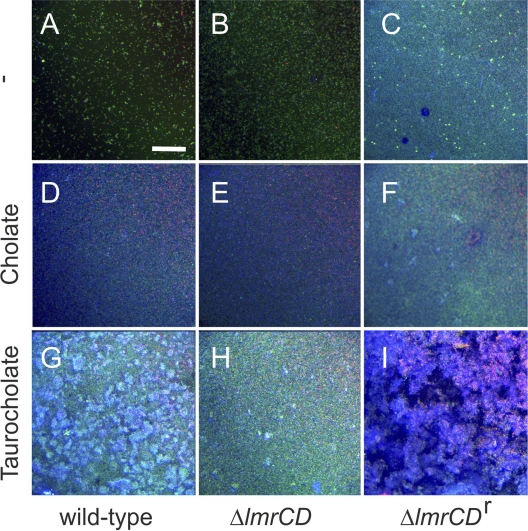

Extracellular polymeric substance formation.

Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) are known to play an important role in biofilm formation. EPS formation was visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (Fig. 3) using the dye calcofluor (26), which stains the extracellular matrix blue. In addition, the BacLight Live/Dead stain with the dyes SYTO9 (green) and propidium iodide (red) was used to differentiate between viable and nonviable cells, respectively (1). Under normal conditions of growth, the ΔlmrCDr cells produced more EPS than the parental and wild-type cells (Fig. 3A to C). Exposure to 3 mM cholate resulted in a partial disruption of biofilms of wild-type and ΔlmrCD cells, as evidenced by the high dead cell count (Fig. 3D and E). However, at the same time, EPS formation was stimulated. Cholate stimulated both biofilm and EPS formation by ΔlmrCDr cells (Fig. 3F). Remarkably, taurocholate (24 mM) had an even stronger effect on biofilm and EPS formation, in particular with ΔlmrCDr (Fig. 3I) and wild-type (Fig. 3G) cells. These data demonstrate that ΔlmrCDr biofilm cells produce increased levels of EPS.

Fig. 3.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy of biofilms of the L. lactis wild-type (A, D, and G), ΔlmrCD (B, E, and H), or ΔlmrCDr (C, F, and I) strain formed in the absence or presence of sodium cholate (3 mM) or taurocholate (24 mM). Biofilms were staining with the BacLight viability stain, indicating live cells in green and dead cells in red. Calcofluor stains the EPS in blue. The bar marker corresponds to 75 μm in all images.

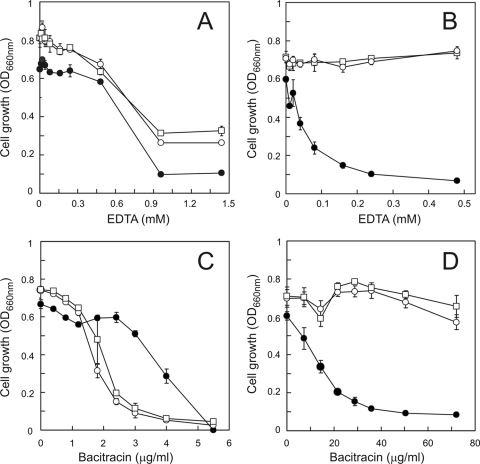

Divalent cation dependence of biofilm formation.

Since divalent metal cations are known to be involved in the maintenance and stability of biofilms (2), the effect of EDTA on biofilm persistence was determined. While planktonic cells of the different L. lactis strains exhibited similar EDTA susceptibilities, with IC50s in the range of 0.7 to 0.8 mM (Fig. 4A), biofilms of wild-type and ΔlmrCD cells were entirely insensitive to high concentrations of EDTA (Fig. 4B). Remarkably, under the same set of conditions, the ΔlmrCDr biofilms collapsed, showing hypersensitivity to EDTA. This suggests that the integrity of the ΔlmrCDr biofilm to a great extent relies on the presence of divalent cations.

Fig. 4.

Influence of EDTA (A and B) and bacitracin (C and D) on the growth of L. lactis wild-type (□), ΔlmrCD (○), and ΔlmrCDr (•) cells. Planktonic (A and C) cells were grown for 12 h in 96-well microtiter plates in GM17 medium containing 0 to 50 mM EDTA or 0 to 80 μg/ml bacitracin. Growth was determined at OD660. Biofilm cells (B and D) were grown for 24 h on pegs immersed in GM17 medium containing 0 to 50 mM EDTA or 0 to 80 μg/ml bacitracin. Biofilm cells were collected and regrown for 18 h in GM17 medium, and growth was determined at OD660.

The susceptibilities of the biofilms to the antimicrobial peptide bacitracin were determined. Bacitracin is a dodecapeptide that inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis in Gram-positive cocci, a process that is divalent metal cation dependent (32). In the planktonic phase, the ΔlmrCDr strain showed a somewhat higher resistance to bacitracin than did wild-type and ΔlmrCD cells (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, biofilms of the last two strains appeared rather insensitive to bacitracin, while the ΔlmrCDr biofilms were very sensitive to this peptide, showing an IC50 of ∼15 μg/ml (Fig. 4D). Possibly, the increased sensitivity to bacitracin relates to a requirement for divalent cations in the integrity of ΔlmrCDr biofilms. On the other hand, the biofilm cells were about 10-fold more resistant to bacitracin than the planktonic cells, which may reflect the more recalcitrant nature of biofilms to antimicrobial agents.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to resolve the physicochemical basis of bile acid resistance in the lactic acid bacterium L. lactis. Our previous work has shown that in planktonic L. lactis cells, the ABC-type MDR transporter LmrCD is a major determinant of drug and bile acid resistance (27). Importantly, cells that lack the lmrCD genes are able to regain bile acid resistance upon prolonged exposure to increasing levels of sublethal cholate concentrations (41). This ΔlmrCDr strain, as used in this study, shows a bile acid resistance which is not efflux based and that, although more effective than LmrCD-mediated cholate resistance, is limited to mostly unconjugated bile acids. Transcriptome analysis and macroscopic visualization of the cells suggest that the cholate resistance of ΔlmrCDr cells is related to cell surface changes (41). In addition, ΔlmrCDr cells show an enhanced flocculation. Recently it has been reported that such cellular aggregates can be considered free-floating biofilms (34). Therefore, we have investigated the biofilm-forming abilities of ΔlmrCDr cells. In the absence of cholate, the cells showed a poor ability to attach to hydrophobic polystyrene surfaces, but attachment was strongly stimulated by the presence of cholate. Contact angle measurements suggest that the cell envelope of the ΔlmrCDr cells is hydrophilic, and this likely makes interactions with the hydrophobic polystyrene surface thermodynamically unfavorable. However, in the presence of cholate a shift in the distribution of the cationic and anionic components of the cell envelope properties is observed, and this results in a reduction in the hydrophilicity. Therefore, biofilm formation on a polystyrene surface is more likely to occur. It thus seems that cholate alters the cell surface properties of the ΔlmrCDr cells, making these cells more effective in colonizing hydrophobic surfaces. It should be stressed that cholate also stimulates biofilm formation of wild-type and parental cells, but the effects with the ΔlmrCDr strain are much more pronounced.

In ΔlmrCDr cells, several cell envelope proteins are differentially expressed. In particular, the cell wall-anchored protein CluA and the serine protease HtrA are upregulated, and both have been implicated in the clumping phenotype in L. lactis (16, 29). The flocculation of the ΔlmrCDr cells in aqueous media might be due to increased levels of CluA (41), a cell wall-anchored adhesin. HtrA is involved in the degradation of misfolded proteins (41) but also in protein processing, such as that of the cell wall protein AcmA (autolysin). In L. lactis, HtrA has been shown to be involved in cell aggregation due to its role in processing of surface proteins (16). In the ΔlmrCDr strain, this may have led to changes in the cell wall protein composition favoring cell adhesion.

Biofilm formation is an intricate multistep phenomenon which begins with an initially weak and reversible adhesion of cells to the surface, gradually leading to a firm and irreversible attachment involving production of exopolymeric material (20). This encompasses polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and other materials and constitutes the major portion of the total volume of a biofilm (31). The changes in overall physicochemical properties of the cell surface of the ΔlmrCDr strain most likely relate to a change in the composition and/or amount of cell wall-associated glycopolymers (15) and polysaccharides (5). The lactococcal cell wall consists of a thick peptidoglycan layer with interspersed teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, surface-exposed proteins, and polysaccharides (10). We focused on EPS in the biofilms because of their role in maintaining biofilm integrity (22) and promoting cell adhesion (8). Even in the absence of cholate, biofilms of the ΔlmrCDr strain produced greater amounts of EPS than wild-type and ΔlmrCD biofilms. EPS formation is further stimulated by cholate and taurocholate. The increase in EPS likely contributes to the observed transition from a hydrophilic to a slightly more hydrophobic cell surface of the ΔlmrCDr cells when they are exposed to cholate. In this respect, some other membrane-acting agents, such as ethanol or cinnamon oil (30), have also been reported to stimulate the production of EPS (13) or alter its composition (35). The biofilm EPS can also serve to sequester ions from the environment (39) and thereby make cells more susceptible to antimicrobials, such as bacitracin, that are cation dependent for their activity. Importantly, EPS has also been shown to reduce the penetration of some antibiotics into the biofilm (37), and this may also contribute to the overall bile acid resistance of the biofilms. Another critical event in adhesion leading to biofilm development is the preconditioning of the surface by macromolecules (6). Surfactant-like molecules may, for instance, promote cell adhesion to the surface, as in the case of surfactants with long acyl chains that elicit a maximum adhesive response (33). Cholate may have a similar effect, although our observations suggest that this is not a general detergent-like effect since structurally related (i.e., steroidal) molecules, like CHAPS, are only weakly effective.

L. lactis encodes a large number of (putative) efflux pumps (41). Several of these, such as the MFS-type pump LmrP (4) and the ABC-type transporters LmrA (40) and LmrCD (27), have been well characterized and show drug extrusion activity in planktonic cultures. Wild-type lactococcal biofilms are more resistant to daunomycin and cholate than is the ΔlmrCD strain. Strikingly, wild-type L. lactis biofilm cells carrying a multicopy plasmid encoding LmrCD exhibit an even higher level of resistance and can tolerate cholate concentrations even up to 20 mM. This demonstrates that the MDR transporter LmrCD also plays a prominent role in drug and bile acid resistance during biofilm formation and persistence, in addition to the general impermeable nature of the biofilm matrix. Future experiments should determine which other transport systems contribute to biofilm resistance and persistence.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A.H.Z. was supported by a scholarship from the Higher Education Commission, Government of Pakistan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Auschill T. M., et al. 2001. Spatial distribution of vital and dead microorganisms in dental biofilms. Arch. Oral Biol. 46:471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banin E., Brady K. M., Greenberg E. P. 2006. Chelator-induced dispersal and killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells in a biofilm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2064–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Begley M., Kerr C., Hill C. 2009. Exposure to bile influences biofilm formation by Listeria monocytogenes. Gut Pathog. 1:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bolhuis H., et al. 1995. The Lactococcal lmrP gene encodes a proton motive force-dependent drug transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26092–26098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boonaert C. J., Rouxhet P. G. 2000. Surface of lactic acid bacteria: relationships between chemical composition and physicochemical properties. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2548–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bos R., van der Mei H. C., Busscher H. J. 1999. Physico-chemistry of initial microbial adhesive interactions—its mechanisms and methods for study. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:179–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burmolle M., et al. 2006. Enhanced biofilm formation and increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and bacterial invasion are caused by synergistic interactions in multispecies biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3916–3923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Czaczyk K., Myszka K. 2007. Biosynthesis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and its role in microbial biofilm formation. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 16:799–806 [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Kievit T. R., et al. 2001. Multidrug efflux pumps: expression patterns and contribution to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1761–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delcour J., Ferain T., Deghorain M., Palumbo E., Hols P. 1999. The biosynthesis and functionality of the cell-wall of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 76:159–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. den Hengst C. D., et al. 2005. The Lactococcus lactis CodY regulon: identification of a conserved cis-regulatory element. J. Biol. Chem. 280:34332–34342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Ruyter P. G., Kuipers O. P., de Vos W. M. 1996. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3662–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeVault J. D., Kimbara K., Chakrabarty A. M. 1990. Pulmonary dehydration and infection in cystic fibrosis: evidence that ethanol activates alginate gene expression and induction of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 4:737–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drenkard E. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microbes Infect. 5:1213–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fedtke I., et al. 2007. A Staphylococcus aureus ypfP mutant with strongly reduced lipoteichoic acid (LTA) content: LTA governs bacterial surface properties and autolysin activity. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1078–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Foucaud-Scheunemann C., Poquet I. 2003. HtrA is a key factor in the response to specific stress conditions in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224:53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank K. L., Reichert E. J., Piper K. E., Patel R. 2007. In vitro effects of antimicrobial agents on planktonic and biofilm forms of Staphylococcus lugdunensis clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:888–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Funasaki N., et al. 2006. Micelle formation of bile salts and zwitterionic derivative as studied by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lipids 142:43–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giaouris E., Chapot-Chartier M. P., Briandet R. 2009. Surface physicochemical analysis of natural Lactococcus lactis strains reveals the existence of hydrophobic and low charged strains with altered adhesive properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 131:2–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heilmann C., Hussain M., Peters G., Gotz F. 1997. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1013–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hindre T., Bruggemann H., Buchrieser C., Hechard Y. 2008. Transcriptional profiling of Legionella pneumophila biofilm cells and the influence of iron on biofilm formation. Microbiology 154:30–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hughes K. A., Sutherland I. W., Clark J., Jones M. V. 1998. Bacteriophage and associated polysaccharide depolymerases—novel tools for study of bacterial biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:583–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimoto H., Nomura M., Kobayashi M., Mizumachi K., Okamoto T. 2003. Survival of lactococci during passage through mouse digestive tract. Can. J. Microbiol. 49:707–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koza A., Hallett P. D., Moon C. D., Spiers A. J. 2009. Characterization of a novel air-liquid interface biofilm of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. Microbiology 155:1397–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kvist M., Hancock V., Klemm P. 2008. Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7376–7382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Labbate M., et al. 2007. Quorum-sensing regulation of adhesion in Serratia marcescens MG1 is surface dependent. J. Bacteriol. 189:2702–2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lubelski J., de Jong A., van Merkerk R., Agustiandari H., Kuipers O. P., Kok J., Driessen A. J. 2006. LmrCD is a major multidrug resistance transporter in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 61:771–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lubelski J., Mazurkiewicz P., van Merkerk R., Konings W. N., Driessen A. J. 2004. ydaG and ydbA of Lactococcus lactis encode a heterodimeric ATP-binding cassette-type multidrug transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 279:34449–34455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luo H., Wan K., Wang H. H. 2005. High-frequency conjugation system facilitates biofilm formation and pAMbeta1 transmission by Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2970–2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nuryastuti T., et al. 2009. Effect of cinnamon oil on icaA expression and biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6850–6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Priester J. H., et al. 2006. Enhanced exopolymer production and chromium stabilization in Pseudomonas putida unsaturated biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1988–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qi Z. D., et al. 2008. Characterization of the mechanism of the Staphylococcus aureus cell envelope by bacitracin and bacitracin-metal ions. J. Membr. Biol. 225:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santos L., et al. 2007. The effect of octylglucoside and sodium cholate in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesion to soft contact lenses. Optom. Vis. Sci. 84:429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schleheck D., et al. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 preferentially grows as aggregates in liquid batch cultures and disperses upon starvation. PLoS. One 4:e5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmit J., Nivens D., White C., Flemmings C. 1995. Changes of biofilm properties in response to sorbed substances—an FTIR-ATR study. Water Sci. Technol. 32:149–155 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shirtliff M. E., et al. 2009. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2392–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spoering A. L., Lewis K. 2001. Biofilms and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J. Bacteriol. 183:6746–6751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tabak M., et al. 2007. Effect of triclosan on Salmonella typhimurium at different growth stages and in biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 267:200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tenuta L. M., Del Bel Cury A. A., Bortolin M. C., Vogel G. L., Cury J. A. 2006. Ca, Pi, and F in the fluid of biofilm formed under sucrose. J. Dent. Res. 85:834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Veen H. W., et al. 1996. Multidrug resistance mediated by a bacterial homolog of the human multidrug transporter MDR1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:10668–10672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zaidi A. H., et al. 2008. The ABC-type multidrug resistance transporter LmrCD is responsible for an extrusion-based mechanism of bile acid resistance in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 190:7357–7366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang L., Mah T. F. 2008. Involvement of a novel efflux system in biofilm-specific resistance to antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 190:4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.