Abstract

Mycophenolic acid (MPA) is the active ingredient in the increasingly important immunosuppressive pharmaceuticals CellCept (Roche) and Myfortic (Novartis). Despite the long history of MPA, the molecular basis for its biosynthesis has remained enigmatic. Here we report the discovery of a polyketide synthase (PKS), MpaC, which we successfully characterized and identified as responsible for MPA production in Penicillium brevicompactum. mpaC resides in what most likely is a 25-kb gene cluster in the genome of Penicillium brevicompactum. The gene cluster was successfully localized by targeting putative resistance genes, in this case an additional copy of the gene encoding IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH). We report the cloning, sequencing, and the functional characterization of the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster by deletion of the polyketide synthase gene mpaC of P. brevicompactum and bioinformatic analyses. As expected, the gene deletion completely abolished MPA production as well as production of several other metabolites derived from the MPA biosynthesis pathway of P. brevicompactum. Our work sets the stage for engineering the production of MPA and analogues through metabolic engineering.

INTRODUCTION

Mycophenolic acid (MPA) is a fungal metabolite that was initially discovered by Bartolomeo Gosio in 1893 as an antibiotic against anthrax bacillus, Bacillus anthracis (see the excellent review by R. Bentley for details [4]). MPA has also been reported to possess antiviral (8, 17), antifungal (35), antibacterial (28, 48), antitumor (49), and antipsoriasis (19) activities. Most importantly, it is being used as an immunosuppressant in kidney, heart, and liver transplantation patients and is marketed under the brands CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil; Roche) and Myfortic (mycophenolate sodium; Novartis). Mycophenolate, the active component in both drugs, inhibits IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH). This enzyme is the rate-controlling enzyme in GMP biosynthesis (12, 47). The proliferation of B and T lymphocytes is inhibited in the presence of MPA, because these cell types rely entirely on the IMPDH dependent de novo pathway for purine biosynthesis. Unlike B and T lymphocytes, most other cell types express the IMPDH-independent salvage pathway, which allows purine production despite inhibition of IMPDH by MPA. This explains why MPA has found excellent use as an immunosuppressive pharmaceutical (2).

MPA is a meroterpenoid consisting of an acetate-derived phthalide nucleus and a terpene-derived side chain (6). The acetate origin of the phthalide identifies this part of the molecule as a polyketide, which refers to an enormously diverse group of bioactive compounds (16). Polyketide biosynthesis is catalyzed by polyketide synthases (PKSs), which are structurally and mechanistically closely related to fatty acid synthases (FASs) (16). Several different types of PKSs have been identified in nature, and among the fungal PKSs are large multifunctional enzymes with multiple active domains that are used iteratively during polyketide biosynthesis (3, 16).

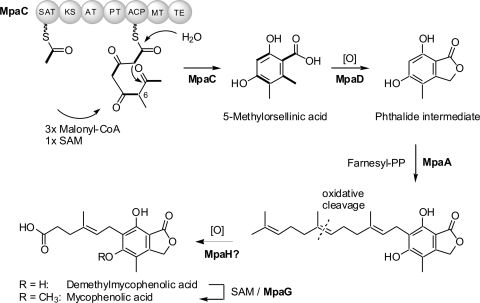

MPA biosynthesis has been investigated extensively at the chemical level by using labeled substrates and by feeding cell cultures with analogues. This has provided the first insights into the reaction steps of MPA biosynthesis (5–7, 10, 13, 33, 44) and resulted in the model shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA building blocks to MPA. Ad, adenosyl; Enz, enzyme; PP, pyrophosphate; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine.

The production of the phthalide moiety of MPA is initiated by the assembly of a nonreduced, methylated tetraketide (Fig. 1, MpaC). Hence, the MPA PKS as a minimum contains the starter unit acyl carrier protein transacylase (SAT), β-ketoacylsynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), product template (PT), acyl carrier protein (ACP), and methyltransferase (MT) domains. The fact that no reductive steps occur during biosynthesis indicates that the PKS likely does not contain any reductive domains. Moreover, the proposed MT domain could be involved in the methylation of the C-6 position, as shown in Fig. 1.

Gene clusters of biologically active metabolites typically harbor genes which confer the necessary tolerance to the compounds. As described, MPA is a known inhibitor of IMPDH, which converts IMP to XMP in the de novo pathway of GMP biosynthesis (47). This is an important reaction in almost all living organisms. Sequence analyses of IMPDH genes from different organisms show that this gene is highly conserved among different species.

To advance the understanding of MPA biosynthesis, we set out to identify the gene cluster that is responsible for production of this important compound. Since only very few fungal PKSs have been characterized that produce methylated, nonreduced polyketides, it is difficult to isolate a gene encoding such a PKS simply by using DNA sequence information from close PKS homologues. We therefore took another approach, one which was based on the assumption that an organism is often resistant to the secondary metabolites it produces. For example, gene clusters responsible for production of lovastatin and compactin have been reported to contain homologues of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (CoA) reductase, which is a target for these PKSs. In this way, the tolerance to these statins is increased. Similarly, we hypothesized that Penicillium brevicompactum needs to be resistant to MPA and that the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster may therefore contain a gene encoding an IMPDH homologue (43, 44). Using this rationale, we indeed identified a putative MPA biosynthesis gene cluster. Here we report the discovery of a PKS (mpaC) responsible for MPA backbone synthesis that resides in a putative gene cluster with a total of eight genes. We propose that this gene cluster functions as the molecular basis for MPA production in P. brevicomapctum, based on findings with a deletion strain of mpaC that conclusively showed that MpaC is the PKS involved in MPA biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

P. brevicompactum IBT23078 was obtained from the strain collection at the Center for Microbial Biotechnology at the Technical University of Denmark and used as the source for genomic DNA and fungal transformation. Plasmid pAN7-1 (GenBank accession number Z32698.1) harboring the hygromycin resistance cassette under the control of the gpdA promoter from Aspergillus nidulans was used as a template for constructing the gene-targeting cassette. Manipulation of plasmid DNA and introduction of plasmids into Escherichia coli DH5α by chemical transformation were carried out according to standard procedures (41).

Media and culture conditions.

P. brevicompactum was grown on minimal medium (MM) containing 1% glucose, 10 mM NaNO3, 1× salt solution (14), and 2% agar at 25°C for 7 days to generate spores. Selection of P. brevicompactum transformants was performed on selective MM supplemented with 1 M sorbitol, 2% glucose, and 300 μg/ml hygromycin at 25°C for 5 days. Yeast extract-sucrose medium (YES; 20 g/liter yeast extract, 150 g/liter sucrose, 0.5 g/liter MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.01 g/liter ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 0.005 g/liter CuSO4 · 5H2O, 20 g/liter agar) was used to grow cultures for the genomic DNA isolation and metabolite isolation. Bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium with 100 μg/ml ampicillin.

Primers used in this study.

All primers used in this study are listed in the supplemental material.

Identification of the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster: isolation of intact chromosomal DNA for the construction of a BAC library of P. brevicompactum. (i) Growth conditions.

P. brevicompactum was grown for 21 h in shake flasks without baffles with shaking at 150 rpm in both MM and YES medium at 25°C. MM contained 10 g/liter glucose, 10 mM NaNO3, 0.52 g/liter KCl, 0.52 g/liter MgSO4, 1.52 g/liter KH2PO4, 4 × 10−4 g/liter CuSO4 · 5H2O, 4 × 10−5 g/liter Na2B2O7 · 10H2O, 8 × 10−4 g/liter FeSO4 · 7H2O, 8 × 10−4 g/liter MnSO4 · 2H2O, 8 × 10−4 g/liter Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 8 × 10−4 g/liter ZnSO4 · 7H2O. Trace metal solution was added to the YES medium to ensure the following minimum concentrations: 4 × 10−4 g/liter CuSO4 · 5H2O, 4 × 10−5 g/liter Na2B2O7 · 10H2O, 8 × 10−4 g/liter FeSO4 · 7H2O; 8 × 10−4 g/liter MnSO4 · 2H2O; 8 × 10−4 g/liter Na2MoO4 · 2H2O; 8 × 10−4 g/liter ZnSO4 · 7H2O.

(ii) Harvesting of biomass and protoplasting.

The biomass was harvested by filtration and thoroughly rinsed with sterile 0.9% NaCl. The biomass from one flask was resuspended in 50-ml Falcon tubes with 20 ml of protoplasting solution consisting of 40 mg/ml Glucanex, 1.8 M MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.3). The protoplasting reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 h with mild shaking (60 rpm). The protoplasts were harvested after 2 h as described by Johnstone et al. (26) and diluted 1:1 with 1.0% low-melting-point agarose in GMB solution (0.9 M sorbitol, 0.125 M EDTA, 0.01 M Tris-Cl [pH 7.5]; filter sterilized) at 37°C in a water bath. The final protoplast concentration was 1 × 108 to 2 × 108 ml−1. Once set, the plugs were placed into a 50-ml Falcon tube and treated by adding proteinase K to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml in NDS buffer (0.5 M EDTA, 0.01 M Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 2% sodium lauroyl sarcosinate). The plugs were left to incubate at 50°C with gentle rocking for 12 h, after which the buffer was changed and the washing continued for another 12 h. The detergent was then removed by four 1-h washes in 50 ml 0.5 M EDTA at room temperature with gentle rocking. Agarose plugs were stored in 0.5 M EDTA at 4°C.

Construction of PBBAC from the gel plugs was performed by Amplicon Express, Pullman, WA; PBBAC consisted of 3,072 clones with average inserts of 110 kb. pECBAC1 contains the chloramphenicol resistance marker.

Screening of PBBAC.

Probing of PBBAC was performed using PCR products and RapidHyb hybridization buffer (Amersham-Pharmacia). The washing temperature was 65°C. Isolation of bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) from PBBAC was performed using Jetstar 2.0 (Genomed, Löhne, Germany).

Southern blot hybridization of BACs.

In order to verify that correct BACs were identified and picked from PBBAC, Southern blots of enzymatically (HindIII and XbaI)-digested BACs were constructed using standard techniques and probed with the original probe. Approximately 2 μg of each BAC was digested and blotted onto a membrane as described by Radner (41). RapidHyb hybridization buffer (Amersham-Pharmacia) was used for probing, and the washing temperature was 65°C. The insert lengths of the isolated BACs were tested by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Degenerate PCR.

Degenerate PCR was used to obtain all probes for screening of PBBAC. The technique was used routinely to amplify fragments of PKS genes in a two-step procedure: first, an initial PCR with genomic DNA as template, followed by a second PCR with 2 μl of the product from the first reaction mixture as template. The amplifications were obtained using Taq polymerase (New England BioLabs) under the following standard conditions in 50-μl reaction volumes: 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, pH 8.3; 20°C), primers at 0.5 to 1.0 μM, deoxynucleoside triphosphates at 200 μM, 2.5 U of enzyme, and approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA or 2 μl of the first PCR product as templates. Samples were run with hot start, an initial denaturation step of 2 min at 94°C, and the following cycle parameters (for 30 cycles): 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s (with a 0.5°C reduction in annealing temperature per cycle with genomic DNA as template, or at a fixed 50°C in the second-round PCR), and 72°C for 2 min.

Isolation of genomic DNA for PCR.

Genomic DNA from P. brevicompactum was isolated by spooling high-molecular-weight DNA onto a shepherd's crook as described in standard laboratory manuals (41).

Sequencing and annotation of genes on BACs.

The BACs were sequenced by Macrogen Inc., Seoul, South Korea. The annotation of sequenced BACs was carried out using several bioinformatic tools. Primarily, a Blastx similarity search located open reading frames (ORFs) with similarities to proteins submitted to GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB. When the genes were identified, the exon-intron structures were determined by running analyses using GENSCAN (http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html) (9), HMMGene (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/HMMgene/) (29), NetAspGene 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetAspGene/) (50), and Genesplicer (http://www.cbcb.umd.edu/software/GeneSplicer/gene_spl.shtml) (40). Blastx and Blastp similarity searches were performed using the online web interface at http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

Bioinformatic characterization of predicted proteins: detection of transmembrane regions.

All predicted protein sequences were submitted to the Phobius prediction server at http://phobius.cgb.ki.se/(27), which determines transmembrane regions in the proteins. Signal peptides were predicted using SignalP3.0 (www.cbs.dtu.dk) (18) as well as PSort II (www.wolfpsort.org).

Functional analysis of MpaC. (i) Oligonucleotides, PCR, and sequencing analyses.

Oligonucleotides used to generate bipartite PCR fragments and to investigate the targeting pattern were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (United Kingdom). All PCRs were performed using Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. PCR products were purified from agarose gels using Illustra DNA and a gel band purification kit (GE Healthcare). Sequencing of PCR fragments obtained from transformants was performed by MWG Biotech.

(ii) Construction of gene-targeting substrates.

To construct the mpaC deletion strain, the bipartite gene-targeting method was used and the hygromycin resistance gene (hph) was used as a selectable marker (38). Each part of the fragment of bipartite substrates consists of a targeting fragment and a marker fragment. In order to ensure high homologous recombination efficiency, mpaC-flanking regions of 2.65 (upstream) and 2.67 kb (downstream) were used. The sequences were amplified from genomic DNA of P. brevicompactum by using primer pairs KO-MpaC-UF/KO-MpaC-URa and KO-MpaC-DFa/KO-MpaC-DR, respectively. The two fragments containing the hygromycin B resistance cassette (hph) were amplified from pAN7-1, a vector carrying the hph cassette under the control of the gpdA promoter from A. nidulans. To generate a bipartite gene-targeting substrate (37), the two-thirds upstream portion of hph (1.72 kb) was amplified using primers Upst-HygF-b and Upst-HygR-N, whereas the two-thirds downstream of hph (1.64 kb) was amplified using primers Dwst-HygF-N and Dwst-HygR-A.

To obtain the primary bipartite substrate, the fragment upstream of mpaC was fused to the two-thirds N-terminal hph fragment by PCR using primers KO-MpaC-UF and Upst-HygR-N. Similarly, the secondary bipartite substrate was generated by fusing the C-terminal two-thirds fragment of hph to the fragment downstream of mpaC by PCR with primers Dwst-HygF-N and KO-MpaC-DR.

(iii) Fungal transformation.

Genetic transformation of P. brevicompactum was carried out according to a slightly modified version of the procedure described by Nielsen et al. (38). Twenty-one-hour-old fungal mycelium was used for protoplast preparation. Protoplasts were prepared by the use of Glucanex (Novozymes A/S, Denmark), at a concentration of 40 mg/ml in protoplasting buffer. All transformation experiments were performed with 2 × 105 protoplasts in 200 μl transformation buffer. Between 2 and 4 μg of each purified fusion PCR fragment was used for transformation, and transformants were selected on MM supplemented with 1 M sorbitol, 2% glucose, and 300 μg/ml hygromycin at 25°C for 5 days. For the positive-control experiment, P. brevicompactum was transformed with pAN7-1 plasmid. Transformants were purified twice by streaking spores to obtain single colonies on MM containing 150 μg/ml hygromycin.

To purify transformants, single spores were isolated using a micromanipulator and individually placed in well-separated positions on Czapek yeast agar (CYA) plates. Germination efficiency of the spores was high on CYA plates, and spores from spore colonies could be obtained within 5 days of incubation at 25°C in the dark for further analysis.

(iv) Chemical characterization of mpaC::hph.

Each purified transformant was grown on YES medium (42) at 25°C for 7 days. Three 6-mm-diameter plugs were then taken from each strain and transferred to a 2-ml vial, and 1 ml of acetonitrile (ACN) was added. The plugs were placed in an ultrasonication bath for 60 min. The ACN was filtered and transferred to a new 2-ml clean vial, in which the organic phase was evaporated to dryness by applying a nitrogen airflow at 30°C. The residues were redissolved ultrasonically for 10 min in 150 μl of a ACN-H2O (1:1, vol/vol) mixture. Samples of 3 μl were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–UV/Vis by using 15 to 100% ACN for 20 min on a Luna C18 column (19). HPLC-UV/Vis high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) analysis was performed with an Agilent 1100 system (Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a diode array detector and coupled to an LCT apparatus (Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom) equipped with an electrospray (ESI) instrument (36, 37). Separation of 3-μl samples was performed on a 100- by 2-mm inner diameter, 2.6 μm Kinetex C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) using a linear water-ACN gradient at a flow of 0.400 ml/min from 10 to 65% ACN within 14 min, then to 100% ACN in 3 min, followed by a plateau at 100% ACN for 3 min. Both solvents contained 20 mM formic acid. Samples were analyzed both in ESI− and ESI+ modes. To identify the MPA peaks, we included an MPA standard in our analyses. Other peaks were tentatively identified by searching the accurate mass in the ∼13,000 fungal metabolites reported in Antibase 2009 (31).

(v) Molecular characterization of mpaC::hph.

The mpaC::hph allele was verified by PCR and by Southern blotting. Four diagnostic PCRs were performed. Two reactions were designed to detect the mpaC::hph allele by using primer pairs in which one of the primers was located within the hph-containing cassette and the other was outside either the upstream or the downstream region used for gene targeting. Similarly, the presence of the wild-type mpaC locus was determined using primer pairs in which one of the primers was located in the mpaC gene and the other either in the upstream or in the downstream region used for gene targeting. Specifically, the primer pairs used to detect the insertion of the hph cassette were BGHA687/Upst-HygR-N and Dwst-HygF-N/BGHA688. The primer pairs used to detect the presence of mpaC were BGHA687/BGHA471 and BGHA148X/BGHA688.

Southern blotting was carried out using the Biotin chromogenic detection kit (Fermentas, Germany) and a biotin DecaLabel DNA labeling kit (Fermentas, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs from wild-type P. brevicompactum and the mpaC::hph strain were used for Southern blotting. The probe was PCR amplified using primers BGHA696 and BGHA697.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster can be found in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html) under accession number HQ731031.

RESULTS

Identification of the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster.

A part of the IMPDH gene from P. brevicompactum was cloned using primers IMP_FW and IMP_RV, which were both designed based on conserved regions in five putative IMPDH gene sequences from the following fungi (Uniprot IDs shown in parentheses): Pneumocystis carinii (Q9UVLO), Aspergillus funigatus (Q4WHZ9), Neurospora crassa (Q7SFX7), Kluyveromyces lactis (Q6CWA8), Candida glabrata (Q6FM59). A 1,115-bp PCR product was obtained and cloned into the pGEMT vector system, and subsequent sequence similarity analyses showed that the amplified product was 92% identical in 202 amino acid residues to the putative IMPDH from A. fumigatus. The obtained PCR product was then used for screening a DNA library (referred to as PBBAC) of P. brevicompactum.

PBBAC was constructed with the aim of obtaining a DNA library with a statistically determined coverage of approximately 10-fold, calculated based on a genome size of approximately 30 Mbp. Other Penicillium spp. have genomes reported to range from 26 Mbp (P. marneffei) to 34 Mbp (P. chrysogenum). PBBAC was screened with the obtained PCR product of the IMPDH gene. As the PCR product was not subcloned prior to screening PBBAC, the probe may have contained two or more amplicons. The screening resulted in a total of 24 hybridization signals, which led us to suspect that two IMPDH homologues were present. To investigate whether the hybridizations really were the result of the presence of two IMPDH homologues, five BACs were randomly selected, digested with HindIII and XbaI, and used for a Southern blot assay and hybridized to the IMPDH probe. The results clearly showed that the BACs hybridized in two distinct patterns that grouped the BACs into two groups (data not shown): the first group (1-B12, 1-B16, and 1-H11) had hybridization signals at 1 kb, 3 kb, and >20 kb. The second group (1-C23 and 1-E13) shared hybridization signals at 2 kb and 5 kb. The only fungus known to have more than one IMPDH gene is the distantly related Saccharomyces cerevisiae, whereas fungi more closely related to P. brevicompactum, like Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus terreus, Magnaporthe grisea, and N. crassa, only contain a single IMPDH gene (data not shown). This strongly suggested that P. brevicompactum, unlike closely related fungi, contains two genes encoding IMPDH. This was consistent with, but not direct evidence for, our hypothesis that one IMPDH gene resides in the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster.

As probing for MPA biosynthesis-related genes other than IMPDH had previously proven unsuccessful, it seemed that one way to identify the group of BACs most likely to harbor the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster was through process of elimination. If we could identify the group of BACs containing the IMPDH gene that does not reside in the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster, the other group of BACs would be candidates for carrying the MPA biosynthesis genes. There were several assumptions here: first, that it would be possible to identify the IMPDH gene based on the genetic context and synteny with related non-MPA-producing fungi; second, that the other IMPDH gene in P. brevicompactum did not just occur from an unrelated gene duplication event but rather resided in the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster. Based on these assumptions, the BACs analyzed above (1-B12, 1-C23, 1-E13, 1-B16, and 1-H11) were subjected to further analyses.

We investigated whether partial synteny in non-MPA-producing fungi could be detected in the regions surrounding IMPDH genes. Hence, genomic regions around IMPDH genes from several closely related fungal genomes were aligned, and a conserved gene encoding a “rasGTPase-activating protein” was located in all fungi at a distance between 1.5 and 4 kb from the IMPDH gene. It is uncertain whether this gene in fact is involved in GMP biosynthesis; however, as the alignment of this region in all cases showed the presence of this gene, it was assumed that if this gene was located on some of the BACs identified with the IMPDH probe, these BACs would most likely harbor the original IMPDH gene. Two degenerate primers (GTP_FW/RV) were designed based on conserved regions of the identified “rasGTPase-activating protein” sequences. Degenerate PCR was carried out with the hybridizing BACs 1-C23, 1-E13, 1-B12, 1-B16, and 1-H11 as templates. Three of these (1-B12, 1-B16, and 1-H11) resulted in a PCR product of the expected length (approximately 2 kb), whereas the remaining two (1-C23 and 1-E13) did not (data not shown). These findings corresponded exactly to the grouping observed in the Southern blot results, and sequencing of the PCR product verified that the amplified region was 78% identical on the amino acid level to the rasGTPase-activating proteins of A. terreus (GenBank accession number XP_001218147) and Aspergillus oryzae (GenBank accession number BAE62830).

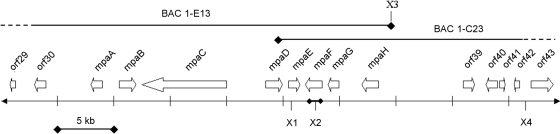

These results showed that the BACs 1-C23 and 1-E13 harbored an IMPDH gene situated in a genetic context different from the IMPDH gene present in most fungi. After verifying the length of the DNA inserts of BACs 1-C23 and 1-E13 to >100 kb each, BAC 1-C23 was sequenced and annotated. This revealed a putative IMPDH gene, mpaF (Fig. 2), flanked by the polyketide biosynthesis genes mpaD, mpaE, mpaG, and mpaH. However, the PKS as well as other genes necessary for MPA production were missing on the BAC. Subsequent BAC walking resulted in the identification of several overlapping BACs, of which one, 1-E13, turned out to have an insert that contained the missing region. Sequencing and sequence analyses of both 1-C23 and 1-E13 revealed the putative gene pattern depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Organization of the 25-kb MPA biosynthetic gene cluster. The gene cluster is flanked by a 4-kb and a 7-kb region with no similarities to known sequences. These regions are therefore thought to present natural boundaries of the gene cluster. The block arrows indicate the putative genes and the direction of their transcription. The genes between the boundaries are designated, from mpaA to mpaH. X1 to X4, XbaI restriction sites. A physical map of the BACs overlapping the cluster is shown. The X3 site is located in the pECBAC1 cloning vector and is not part of the P. brevicompactum genomic DNA insert. The bold line around X2 indicates a region that hybridized with the IMPDH gene probe used for the screening of PBBAC.

The DNA region upstream of mpaA has no similarity to any known proteins. Furthermore, the nearest identified ORFs upstream of mpaA have similarities to ribosome biogenesis protein Rsa4 (ORF30), DNA mismatch repair protein Msh4 from Coccidioides posadasii (ORF29), and a C2H2 Zn finger-carrying protein (ORF28) with weak similarity to ubiquitin ligase E3 protein, which may also be involved in DNA repair. The nearest putative genes downstream of mpaH are a DAHP synthase homologue (88% identical; ORF39), two hypothetical proteins (ORF40 and ORF41) with no characterized homologues, and a glycoside hydrolase (57% identical; ORF42). Hence, neither upstream nor downstream of the proposed MPA biosynthesis gene cluster are the putative genes predicted to be involved in MPA biosynthesis. Upstream, the gene products are predicted to be involved in certain DNA binding or repair reactions, whereas downstream, the predicted gene products may be involved in central metabolism, such as aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and sugar degradation reactions. Hence, the borders of the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster are predicted to be mpaA and mpaH.

Bioinformatic characterization of the MPA gene cluster.

The annotation of the sequenced BACs revealed a 25-kb DNA region containing several predicted ORFs similar to polyketide biosynthetic genes. The region is flanked by 4-kb and 7-kb DNA regions with no predicted genes, and a Blastx analysis confirmed that these regions only have very low similarities to genes in the GenBank database. A Blastx analysis of the gene cluster identified eight regions with high similarities to genes in the nonredundant (nr) GenBank database, and these are denoted mpaA to mpaH in Fig. 2. A GENSCAN analysis detected all eight regions as ORFs, but the GENSCAN algorithm combined several of these regions, resulting in a total of only five predicted genes in the gene cluster. Submission to the hidden Markov model genefinder, HMMGene, and to the exon-intron probability calculator NetAspGene 1.0, resulted in the eight genes listed in Table 1. For one gene (mpaH), the algorithm Genesplicer predicted an additional intron which was not detected by any of the other algorithms. Discrepancies between the predictions were expected, as the algorithms were developed for predictions in organisms as different as Aspergillus (NetAspGene 1.0), Caenorhabditis elegans (HMMGene), Arabidopsis thaliana (GENSCAN), and humans (Genesplicer).

Table 1.

Analysis of putative gene products in the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster

| Putative activity | Size (aa)a | Predicted domains and features | Closest characterized homologueb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (accession no.) | Organism | % similarity (no. of aa) | |||

| Prenyltransferase | 315 | Seven transmembrane helices; CDD UbiA prenyltransferase family | UbiA prenyltransferase (XP_001261885) | Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 | 42 (322) |

| Unknown function | 392 | Type III reverse signal membrane anchor; (CDD none) | Putative dephospho-CoA kinase (ZP_01083610) | Synechococcus sp. | 28 (202) |

| Polyketide synthase | 2448 | SAT domain; CDD KS, AT, PP, MT, esterase | Citrinin PKS (dbj BAD44749.1) | Monascus purpureus | 33 (2,189) |

| P450 monooxygenase | 396 | Possible membrane anchorb; CDD cytochrome P450 | Pisatin demethylase (P450) (gb AAC01762.1) | Nectria hematococca | 35 (346) |

| Zn-dependent hydrolase | 261 | CDD metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily II | AhlD (Zn-dependent hydrolase) (gb AAP57766.1) | Arthrobacter sp. | 32 (84) |

| IMP dehydrogenase (MPA tolerance) | 527 | CDD IMPDH, TIM phosphate binding | IMPDH (gb AAW65380.1) | Candida albicans | 62 (524) |

| O-Methyltransferase | 398 | CDD O-MT; SAM-binding motif and catalytic residues | O-Methyltransferase B (gb ABE60721.1) | Hypocrea virens | 32 (375) |

| Oxidative cleavage | 421 | CDD M-factor, weak similarity to α/β-hydrolase fold 1, C-terminal peroxisomal targeting signal (GKL) | Akt2, AK toxin synthesis (dbj BAA36589.1) | Alternaria alternata | 20 (255) |

aa, amino acids.

Only characterized sequences (as of December 2010) are included as closest characterized homologues here, as sequences with no characterization add no extra information about the function of the MPA biosynthesis genes. dbj, DNA Data Bank of Japan; gb, GenBank.

In order to propose functions of the putative MPA genes, they were subjected to bioinformatic analyses such as Blastx, Blastp, and signal protein and transmembrane predictions, as well as functional domain predictions using CDD (20). A brief overview of these results is presented in Table 1.

In MPA biosynthesis, a tetraketide backbone aromatic ring and a farnesyl group are fused, but according to the bioinformatic analyses only the genes involved in polyketide structure and post-PKS modifications are found within the proposed gene cluster. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the farnesyl-PP used in MPA production is likely to be produced by the normal terpenoid biosynthesis pathway in the fungus.

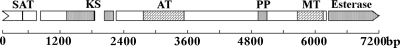

The tetraketide product of MpaC in Fig. 1 is predicted to be produced by MpaC, which has a domain structure similar to a group classified by Kroken as “fungal nonreducing PKS clade III,” with no previously characterized members (30). The fungal nonreducing PKS clade III group of PKSs contains members with the following domain structure: KS, AT, PP (phosphopantetheine attachment site), optional PP, MT, and an optional cyclase domain. Kroken et al. identified only putative genes with this domain structure in Botryotinia fuckeliana, Gibberela zeae, and Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Since then, the citrinin PksCT has been described, which has a similar domain structure except for the terminal thioesterase domain (46). The determined domain structure of MpaC is presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Map of the gene encoding MpaC. The Conserved Domain Database (CDD) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was used to predict the PKS domains. SAT, starter unit acyl carrier protein transacylase; KS, β-ketoacyl synthase; AT, acyltransferase; PP, phosphopantetheine attachment site; MT, methyltransferase; esterase, esterase domain, similar to Aes of E. coli (31a). Gaps indicate predicted introns. The scale indicates the number of nucleotides.

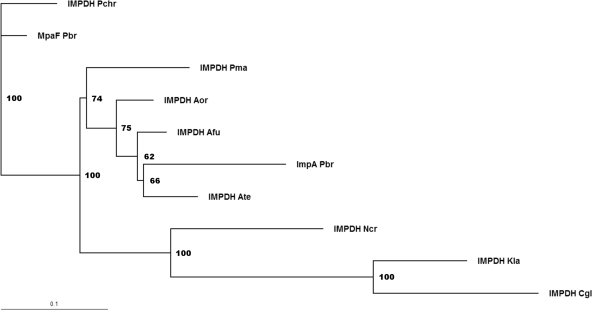

When comparing the sequence obtained after subcloning the IMPDH DNA probe (impA) with mpaF from the MPA gene cluster, several differences were observed over the entire length of the probe. In order to analyze the phylogenetic relationship between MpaF and its homologues, an alignment of MpaF and ImpA as well as of several IMPDH enzymes from filamentous fungi and two other eukaryotes was carried out. The result was used to calculate distances using the nearest-neighbor method, and the result is the unrooted phylogenetic tree presented in Fig. 4. Interestingly, the similarity between MpaF and ImpA was lower than between MpaF and IMPDH from P. chrysogenum. We also compared MpaF with Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus) type 2 IMPDH, as this IMPDH has been analyzed in detail with regard to residues that are essential for activity. We found that residues that have been found essential for activity are conserved in MpaF, which points toward MpaF as indeed a functional IMPDH.

Fig. 4.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree based on alignment of several IMPDH proteins. The tree was bootstraped 100 times, and values (as percentages) are indicated at each branch point. ImpA_Pbr, IMPDH of P. brevicompactum not located in the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster; Pchr, Penicillium chrysogenum; Pbr, Penicillium brevicompactum; Pma, Penicillium marneffei; Aor, Aspergillus oryzae; Afu, Aspergillus fumigatus; Ate, Aspergillus terreus; Ncr, Neurospora crassa; Kla, Kluyveromyces lactis; Cgl, Candida glabrata.

Functional analysis of MpaC.

To functionally characterize the identified gene cluster, a gene deletion strategy for mpaC was undertaken. In order to construct the mpaC deletion strain, the bipartite gene-targeting method (38) was used based on the fungal selectable marker hph, which confers hygromycin resistance to the host. A total of 20 independent transformants were picked randomly, streak purified, and subjected to PCR analysis in order to investigate the gene-targeting events. PCR tests were performed by using primer pairs in which one of the primers was located within the hygromycin cassette (hph) and the other was located either upstream or downstream of the homologous region. Of 20 transformants, 9 transformants were found to have the correct mpaC deletion, based on the expected PCR fragment length. The identified deletion mutants were MPA1.1, -1.3, -1.8, -2.3 to -2.7, and 2.9. The remaining 11 transformants were most likely due to nonhomologous random integration. However, a PCR test of the presence of mpaC in the nine deletion mutants simultaneously showed that mpaC was still present in all nine transformants. This led us to believe that the strains were not adequately purified. Hence, from all nine transformants, in total 198 single spores were started on YES plates, and 49 germinating spores were transferred to new YES plates as three point stabs and subsequently analyzed for MPA production by thin-layer chromatography. MPA was produced in all strains but one (strain 2.3:1). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis of extracts from the wild type and mutant strain 2.3:1 verified that the mutant strain showed no evidence of MPA production. The purified strain contained a clean mpaC::hph allele, as demonstrated by four diagnostic PCRs as well as by Southern blotting (data not shown). Sequencing of the PCR fragments of four of the originally isolated mpaC deletion strains as well as the repurified deletion strain confirmed that mpaC had been deleted as intended.

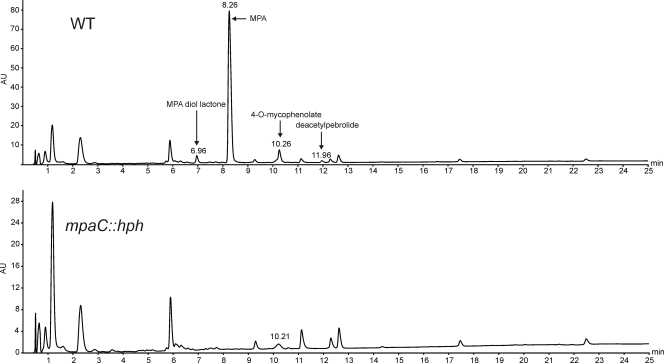

LC/MS analyses of extracts from the wild type and the mpaC::hph mutant strain verified that the mutant strain lost its ability to produce MPA (Fig. 5 and 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition to MPA, the MPA-related compounds MPA diol lactone, 4-O-mycophenolate, and deacetylpebrolide are absent in the mpaC::hph strain (Fig. 5). Reference standards of MPA were coanalyzed. Additional target compounds were identified based on the UV spectrum, retention time, accurate masses, and relative intensities of [M+H] and [M+Na+]. Extracted ion chromatograms for all target peaks were analyzed for all extracts in order to exclude that MPA, MPA diol lactone, 4-O-mycophenolate, or deacetylpebrolide was produced by the mpaC deletion mutant (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of LC results for wild-type (WT) and mpaC::hph strains. Chromatograms are scaled differently to emphasize the absence of MPA production in the mpaC::hph strain. Peaks representing MPA, MPA diol lactone, 4-O-mycophenolate, and deacetylpebrolide are indicated by arrows. For MS data, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

DISCUSSION

The isolation of novel polyketide biosynthesis gene clusters is important for the continued progress in understanding the biosynthetic mechanisms of one of today's industrially most important bioactive group of compounds. The size of the polyketide biosynthesis gene cluster varies for different polyketides. For example, among the reported biosynthetic gene clusters are the compactin biosynthesis gene cluster from Penicillium citrinum (38 kb; AB072893), aurofusarin from Gibberela zeae (25 kb) (21), aflatoxin from Aspergillus parasiticus (82 kb; AY371490), bikaverin from Gibberella fujikuroi (15 kb) (51), and zearalenone from Gibberella zeae (15 kb) (23); several others have also been reported (11, 32). The biosynthesis of these polyketides is dependent on PKSs, transcription factors, transporters, and modifying enzymes encoded by genes residing in the clusters. Hence, in the hunt for the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster, identification of any of the involved genes in the cluster followed by sequencing of up- and downstream regions from this gene would result in the identification of the complete gene cluster.

The identification of an IMPDH homologue located in the proposed MPA biosynthesis gene cluster enabled us to sequence the gene locus. In addition, involvement of MpaC, the gene residing in the proposed gene cluster (mpaA to mpaH) in the biosynthesis of MPA, was demonstrated by deleting mpaC. The mpaC deletion mutant lost the ability to produce MPA and several MPA-related compounds, such as MPA diol lactone, 4-O-mycophenolate, and deacetyl pebrolide. The deletion was confirmed with PCR and Southern blotting.

Notably, MpaC belongs to the group of the few described, nonreducing, fungal PKSs with a functional MT domain. In addition, MpaC contains a starter unit acyl carrier protein transacylase (SAT) domain, which could transfer the starter acetyl-CoA unit to the ACP domain (15). There is a predicted cyclase/thioesterase domain at the C-terminal end of the protein, which could catalyze the cyclization and release of the polyketide from the PKS. Thioesterases, which belong to the same family of proteins, have previously been reported to be involved in chain length determination, cyclization, and lactonization (22). Recently, the long-sought-after PKS required for the biosynthesis of orsellinic acid was discovered (45). Although orsellinic acid and 5-methylorsellinic acid are structurally very similar, the respective amino acid sequences of the synthases orsA (AN7909) and mpaF are only 29% identical globally and 40% identical based on the KS domains. This is in part due to the fact that the orsellinic acid synthase lacks the MT domain present in MpaC.

For lactonization to occur for 5-methylorsellinic acid, the C-3 methyl group must be oxidized to the alcohol, which is a reaction often catalyzed by P450 monooxygenases. Of the MPA biosynthesis enzymes, only MpaD has similarity to a P450 monooxygenase, and thus MpaD is predicted to catalyze this reaction. Raistrick et al. observed that the 3,5-dihydroxyphtalic acid was produced by P. brevicompactum, which is probably derived from orsellinic acid (42). As the structures of 5-methylorsellinic acid and orsellinic acid are almost identical, oxidations of the C-6 methyl group of these two compounds could both be catalyzed by MpaD.

Another enzyme that strongly links the gene cluster to MPA biosynthesis is the predicted prenyltransferase MpaA. The putative prenyltransferase could catalyze prenylation of the phthalide intermediate (Fig. 1) and is predicted to be membrane bound, with seven transmembrane hydrophobic regions.

The step following prenylation in MPA biosynthesis is an oxidative cleavage of the central double bond of the farnesyl chain. The mechanism has been reported to include epoxidation of the double bond, followed by hydrolysis, rearrangement to a ketone, α-hydroxylation, and Woodward reaction of the α-hydroxyketone with C-C bond cleavage and formation of the acid (13). It is uncertain which enzyme in the gene cluster could catalyze this reaction, but MpaH has similarity to Akt2, which is involved in AK toxin biosynthesis in Alternaria alternata. It was recently shown that Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 are localized in peroxisomes, which are involved in fatty acid β-oxidation (25). A PSORT II analysis (34) of the amino acid sequence of MpaH identified a PTS1-like tripeptide GKL at the C-terminal end of this protein, suggesting that MpaH may be located in the peroxisomes. Hence, MpaH could have a similar oxidative role in MPA biosynthesis and, with localization in the peroxisomes, cleave the farnesyl chain.

Demethylmycophenolic acid is converted to MPA by methylation of the 5-hydroxyl group, which could be catalyzed by MpaG, the only O-methyltransferase encoded in the MPA gene cluster (Table 1).

No genes for transcription factors, like MlcR, which is found in the compactin gene cluster (1), could be identified within the MPA biosynthesis gene cluster. Initial studies of MPA production have demonstrated that MPA is produced during the early growth phase on several types of complex media (data not shown), and not only as a response to poor nutrient supply during the stationary phase, when most other secondary metabolites are produced (39). Thus, the question is if there are any conditions under which the strain does not produce MPA, or if the MPA gene cluster is constitutively expressed in P. brevicompactum.

The bioinformatic analysis of the MPA gene cluster does not readily assign catalytic functions to the deduced proteins MpaB, MpaE, and MpaH. Future functional analyses will elucidate the functions of these proteins in MPA biosynthesis.

The discovery of the MPA gene cluster has provided new insights into the biosynthesis of MPA, a very important immunosuppressive drug of today. In summary, the performed experiments show that mpaC is a key gene involved in biosynthesis of MPA by P. brevicompactum, and our results set the groundwork for future experiments to elucidate the remaining intriguing biosynthetic steps in MPA biosynthesis. The accompanying manuscript by Hansen et al. (24) conclusively shows that the polyketide synthase MpaC catalyzes the producion of 5-methylorsellinic acid. A thorough study of several of the catalytic steps in MPA biosynthesis, like the prenyl transfer, heterocyclization, and chain cleavage steps, may result in a deeper understanding of the biosynthesis of this valuable immunosuppressant. Furthermore, construction of higher-yielding mutants would have immediate applicability for the pharmaceutical industry. The knowledge gained through this and future work may lead to the construction of mutants capable of producing interesting new phthalide analogues with fine-tuned biological activities and may have great potential as pharmaceutical drugs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this work was financed by the Danish Research Council for Technology and Production. We also acknowledge the Chalmers Foundation for financial support. Furthermore, the work by B. G. Hansen and U. H. Mortensen was supported by grant numbers 09-064240 and 09-064967 from the Danish Council for Independent Research, Technology and Product Sciences.

We thank Jens C. Frisvad (Technical University of Denmark) for his insightful help with the MPA analyses. We also thank Martin Engelhard Kornholt for his valuable technical assistance in the laboratory.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 11 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abe Y., Ono C., Hosobuchi M., Yoshikawa H. 2002. Functional analysis of mlcR, a regulatory gene for ML-236B (compactin) biosynthesis in Penicillium citrinum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:352–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison A. C., Hovi T., Watts R. W., Webster A. D. 1975. Immunological observations on patients with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, and on the role of de-novo purine synthesis in lymphocyte transformation. Lancet ii:1179–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beck J., Ripka S., Siegner A., Schiltz E., Schweizer E. 1990. The multifunctional 6-methylsalicylic acid synthase gene of Penicillium patulum. Its gene structure relative to that of other polyketide synthases. Eur. J. Biochem. 192:487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bentley R. 2000. Mycophenolic acid: a one hundred year odyssey from antibiotic to immunosuppressant. Chem. Rev. 100:3801–3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Birch A. J., English R. J., Massy-Westropp R. A., Slaytor M., Smith H. 1958. Origin of the nuclear methyl groups in mycophenolic acid. J. Chem. Soc. January:365–368 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Birch A. J., English R. J., Massy-Westropp R. A., Smith H. 1957. Origin of the terpenoid structures in mycelianamide and mycophenolic acid. Mevalonic acid as an irreversible precursor in terpene biosynthesis. Proc. Chem. Soc. (Great Britain) 1957:233–234 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birkinshaw J. H., Bracken A., Morgan E. N., Raistrick H. 1948. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms. 78. The molecular constitution of mycophenolic acid, a metabolic product of Penicillium brevi-compactum Dierckx. Part 2. Possible structural formulae for mycophenolic acid. Biochem. J. 43:216–223 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borroto-Esoda K., Myrick F., Feng J., Jeffrey J., Furman P. 2004. In vitro combination of amdoxovir and the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors mycophenolic acid and ribavirin demonstrates potent activity against wild-type and drug-resistant variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4387–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burge C., Karlin S. 1997. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268:78–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canonica L., et al. 1972. Biosynthesis of mycophenolic acid. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Transl. 21:2639–2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiang Y. M., Oakley B. R., Keller N. P., Wang C. C. 2010. Unraveling polyketide synthesis in members of the genus Aspergillus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86:1719–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cline J. C., Nelson J. D., Gerzon K., Williams R. H., Delong D. C. 1969. In vitro antiviral activity of mycophenolic acid and its reversal by guanine-type compounds. Appl. Microbiol. 18:14–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colombo L., et al. 1982. 6-Farnesyl-5,7-dihydroxy-4-methylphthalide oxidation mechanism in mycophenolic acid biosynthesis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Transl. 31:365–373 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cove D. J. 1966. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crawford J. M., Dancy B. C., Hill E. A., Udwary D. W., Townsend C. A. 2006. Identification of a starter unit acyl-carrier protein transacylase domain in an iterative type I polyketide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16728–16733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crawford J. M., Townsend C. A. 2010. New insights into the formation of fungal aromatic polyketides. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:879–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diamond M. S., Zachariah M., Harris E. 2002. Mycophenolic acid inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing replication of viral RNA. Virology 304:211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emanuelsson O., Brunak S., Heijne G., Nielsen H. 2007. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP, and related tools. Nat. Prot. 2:953–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Epinette W. W., Parker C. M., Jones E. L., Greist M. C. 1987. Mycophenolic acid for psoriasis. A review of pharmacology, long-term efficacy, and safety. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 17:962–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finn R. D., et al. 2008. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D281–D288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frandsen R. J. N., et al. 2006. The biosynthetic pathway for aurofusarin in Fusarium graminearum reveals a close link between the naphthoquinones and naphthopyrones. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1069–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fujii I., Watanabe A., Sankawa U., Ebizuka Y. 2001. Identification of Claisen cyclase domain in fungal polyketide synthase WA, a naphthopyrone synthase of Aspergillus nidulans. Chem. Biol. 8:189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaffoor I., Trail F. 2006. Characterization of two polyketide synthase genes involved in zearalenone biosynthesis in Gibberella zeae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1793–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hansen B. G., et al. 2011. Versatile enzyme expression and characterization system for Aspergillus nidulans, with the Penicillium brevicompactum polyketide synthase gene from the mycophenolic acid gene cluster as a test case. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3044–3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Imazaki A., et al. 2010. Contribution of peroxisomes to secondary metabolism and pathogenicity in the fungal plant pathogen Alternaria alternata. Eukaryot. Cell 9:682–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnstone I. L., Hughes S. G., Clutterbuck A. J. 1985. Cloning an Aspergillus nidulans developmental gene by transformation. EMBO J. 4:1307–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Käll L., Krogh A., Sonnhammer E. L. L. 2007. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction: the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W429–W432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kavanagh F. 1947. Activities of twenty-two antibacterial substances against nine species of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 54:761–766 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krogh A. 2000. Using database matches with for HMMGene for automated gene detection in Drosophila. Genome Res. 10:523–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kroken S., Glass N. L., Taylor J. W., Yoder O. C., Turgeon B. G. 2003. Phylogenomic analysis of type I polyketide synthase genes in pathogenic and saprobic ascomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:15670–15675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Laatsch H. 2009. AntiBase: the natural compound identifier. Wiley-VCH GmbH & Co., Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 31a. Marchler-Bauer A., et al. 2009. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D205–D210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meier J. L., Burkart M. D. 2009. The chemical biology of modular biosynthetic enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38:2012–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muth W. L., Nash C. H. 1975. Biosynthesis of mycophenolic acid: purification and characterization of S-adenosyl-l-methionine: demethylmycophenolic acid O-methyltransferase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 8:321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakai K., Horton P. 1999. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:34–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nicoletti R., De Stefano M., De Stefano S., Trincone A., Marziano F. 2004. Antagonism against Rhizoctonia solani and fungitoxic metabolite production by some Penicillium isolates. Mycopathologia 158:465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nielsen K. F., Mogensen J. M., Johansen M., Larsen T. O., Frisvad J. C. 2009. Review of secondary metabolites and mycotoxins from the Aspergillus niger group. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 395:1225–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nielsen K. F., Smedsgaard J. 2003. Fungal metabolite screening: database of 474 mycotoxins and fungal metabolites for dereplication by standardised liquid chromatography-UV-mass spectrometry methodology. J. Chromatogr. A 1002:111–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nielsen M. L., Albertsen L., Lettier G., Nielsen J. B., Mortensen U. H. 2006. Efficient PCR-based gene targeting with a recyclable marker for Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43:54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nulton C. P., Campbell I. M. 1977. Mycophenolic acid is produced during balanced growth of Penicillium brevicompactum. Can. J. Microbiol. 23:20–27 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pertea M., Lin X., Salzberg S. L. 2001. GeneSplicer: a new computational method for splice site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:1185–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radner S., Li Y., Manglapus M., Brunken W. J. 2002. Joy of cloning: updated recipes. Trends Neurosci. 11:594–595 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raistrick H. 1949. A region of biosynthesis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 199:141–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Regueira T. B. 2007. Ph.D. thesis Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark [Google Scholar]

- 44. Regueira T. B., Nielsen J. B. February 2010. Synthesis of mycophenolic acid. Patent WO/2008/151636

- 45. Schroeckh V., et al. 2009. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14558–14563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shimizu T., et al. 2005. Polyketide synthase gene responsible for citrinin biosynthesis in Monascus purpureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3453–3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith C. M., et al. 1974. Inhibitors of inosinate dehydrogenase activity in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 23:2727–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Torrenegra R. D., Baquero J. E., Calderon J. S. 2005. Antibacterial activity and complete 1H and 13C NMR assignment of mycophenolic acid isolated from Penicillium verrucosum. Rev. Lat. Am. Quim. 33:76–81 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tressler R. J., Garvin L. J., Slate D. L. 1994. Anti-tumor activity of mycophenolate mofetil against human and mouse tumors in vivo. Int. J. Cancer 57:568–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang K., Ussery D. W., Brunak S. 2009. Analysis and prediction of gene splice sites in four Aspergillus genomes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wiemann P., et al. 2009. Biosynthesis of the red pigment bikaverin in Fusarium fujikuroi: genes, their function and regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 72:931–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.