Abstract

In wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans, six cells develop as receptors for gentle touch. In egl-44 and egl-46 mutants, two other neurons, the FLP cells, express touch receptor-like features. egl-44 and egl-46 also affect the differentiation of other neurons including the HSN neurons, two cells needed for egg laying. egl-44 encodes a member of the transcription enhancer factor family. The product of the egl-46 gene, two Drosophila proteins, and two proteins in human and mice define a new family of zinc finger proteins. Both egl-44 and egl-46 are expressed in FLP and HSN neurons (and other cells); expression of egl-46 is dependent on egl-44 in the FLP cells but not in the HSN cells. Wild-type touch cells express egl-46 but not egl-44. Moreover, ectopic expression of egl-44 in the touch cells prevents touch cell differentiation in an egl-46-dependent manner. The sequences of these genes and their nuclear location as seen with GFP fusions indicate that they repress transcription of touch cell characteristics in the FLP cells.

Keywords: TEF, combinatorial control, zinc finger proteins, cell differentiation, transcriptional control

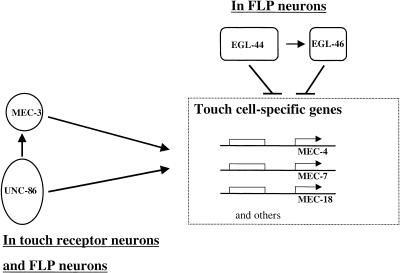

We have been studying the genes needed for the production of a set of six mechanosensory neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for cell fate determination. As with many cellular systems, the combinatorial action of both positively and negatively acting factors determines the developmental fate of these touch cells and restricts their final number to six cells (ALML/R, AVM, PLML/R, and PVM) in adults (Mitani et al. 1993).

Screens for touch-insensitive (Mec) mutants (Chalfie and Sulston 1981; Chalfie and Au 1989) have identified several genes required for either touch cell development or function. The two most proximally acting genes needed for touch cell development are unc-86 and mec-3. unc-86 encodes a POU-type homeoprotein expressed in 57 neurons (Finney et al. 1988; Finney and Ruvkun 1990), including the six touch cells, that is needed not only to produce appropriate touch cell lineages, but also to initiate transcription from the mec-3 gene (Way and Chalfie 1988). mec-3 encodes a LIM-type homeodomain transcription factor. mec-3 mutations do not affect touch cell lineages, but do affect the differentiation of the 10 cells in which it is expressed: the six touch cells, which sense gentle touch to the body, the two FLP neurons, which sense touch at the very tip of the head (Kaplan and Horvitz 1993), and the two PVD neurons, which sense harsh touch to the body (Way and Chalfie 1989). The maintained expression of mec-3 and the subsequent expression of touch cell characteristics require the combined action of both UNC-86 and MEC-3, which appear to form heterodimers (Xue et al. 1992, 1993; Duggan et al. 1998).

The targets of this regulation in the touch cells are several genes needed for the function of these cells as mechanoreceptors. These function genes include the β-tubulin gene mec-7 (Savage et al. 1989, 1994), the channel subunit gene mec-4 (Driscoll and Chalfie 1991), and mec-18, which encodes an apparent CoA synthetase (G. Gu and M. Chalfie, unpubl.). Because wild-type animals express mec-4 and mec-18 exclusively and mec-7 strongly only in the touch cells (Mitani et al. 1993; G. Gu and M. Chalfie, unpubl.), these genes can be used as markers for the differentiation of these cells.

The coexpression of unc-86 and mec-3 in the FLP and PVD cells (Way and Chalfie 1989; Finney and Ruvkun 1990) indicates that other genes restrict touch cell fate to or promote such fate in the six touch cells seen in wild-type animals. Some of these genes have been identified because mutations in them affect the expression of touch cell markers (Mitani et al. 1993). One gene, lin-14, which encodes a nucleoprotein (Ruvkun and Giusto 1989), appears to regulate touch cell differentiation positively; the continued expression of this gene or the absence of its negative regulator, lin-4, leads to a lineage change so that the lineages that usually give rise to the PVD neurons give rise to touch cell-like neurons. The FLP cells normally express lin-14 as well as unc-86 and mec-3. These cells do not express touch cell characteristics because of the action of two genes, egl-44 and egl-46 (Mitani et al. 1993). Mutation of either gene results in a transformation of the FLP cells into cells that resemble the touch cells (Mitani et al. 1993). Instead of differentiating as FLP neurons, the cells in the mutants express the mec-4 and mec-7 touch function genes and have processes that lie adjacent to the normal touch cell processes and that have the large-diameter microtubules and extracellular matrix characteristic of the touch cells.

The egl-44 and egl-46 genes were first identified in a screen for mutants defective in the function of the egg-laying motor neurons, the HSN neurons (Desai et al. 1988; Desai and Horvitz 1989). egl-44 and egl-46 mutants share some common phenotypes: Their absence results in a serotonin-sensitive, imipramine-resistant egg-laying defect, and the mutant animals have multiple HSN defects, including abnormalities in cell migration, axonal outgrowth, and serotonin production. Because other aspects of HSN development are normal in egl-44 and egl-46 mutants, these genes are not thought to specify HSN cell fate completely. The positive role of egl-44 and egl-46 in HSN differentiation contrasts with their apparent negative role in touch cell differentiation, indicating that these genes may have several different activities.

To investigate the restriction of touch cell differentiation further, we cloned egl-44 and egl-46 and found that both genes encode putative transcription factors. Because expression of both genes together in the touch cells causes touch insensitivity and the loss of touch cell-specific gene expression, one function of these genes in the FLP cells is to prevent the cells from differentiating as touch cells.

Results

egl-44 gene encodes a transcription enhancer factor (TEF) protein

egl-44 was previously mapped near position −1.7 on chromosome II (Desai and Horvitz 1989). One of 23 cosmids covering this region (from clr-1 to lin-23; cosmid F28B12) partially rescued the egl-44 Egl phenotype (data not shown). Even greater rescue resulted from the microinjection of a 7.9-kb fragment from F28B12 that contained the second of the four predicted genes (F28B12.2; Table 1; The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998). We identified missense mutations for all three known mutant alleles of egl-44 in this sequence, confirming it as egl-44 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Rescue of egl-44 and egl-46

| Extragenic DNAa

|

Backgrounda

|

Lines

|

% Flpb

|

% EGlb

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | + | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Control | egl-44 | 7 | 95 ± 4 | 100 ± 0 |

| Control | egl-46 | 8 | 97 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 |

| egl-44 (F28B12.2)c | egl-44 | 3 | 50 ± 35 | 25 ± 18 |

| egl-46 (K11G9.4) | egl-46 | 2 | 10 | 25 |

| Pmec-3egl-44 | egl-44 | 3 | 12 ± 12 | 100 ± 0 |

| Pmec-3egl-46 | egl-46 | 3 | 6 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 |

| Punc-86egl-44 | egl-44 | 3 | 26 ± 15 | 39 ± 13 |

| Punc-86egl-46 | egl46 | 3 | 4 ± 2 | 59 ± 17 |

All strains contained an integrated mec-18::gfp array and were injected with the pRF4 plasmid.

Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. (except for egl-46, which is just the mean) for FLP cells expressing the MEC-18::GFP fusion (% Flp) or for egg-bloated animals (% Egl). We examined 30–40 animals for each line.

The plasmid containing F28B12.2 was linearized and cotransformed with wild-type genomic DNA.

Figure 1.

Alignment of EGL-44, Drosophila Scalloped (Sd), and human TEF-5. The predicted exon structure of F28B12.2 differs from the sequence of egl-44 cDNAs in that the former contains an exon before the SL1 splice site and predicts an intron that splits egl-44 exon 6. The sites of the egl-44 mutations are indicated. Even though the n998 and n1087 alleles have the same defect, the initial strains were derived independently (C. Desai and H.R. Horvitz, pers. comm.) and differed in that the latter grew slowly and had a much smaller brood size (Desai and Horvitz 1989). On crossing the n1087 animals to wild type, we obtained a strain, TU2672, that was indistinguishable from the MT2071 [egl-44(n998)] strain. (Triangles) Positions of introns; (red typeface) amino acid residues identical to those in EGL-44; (blue typeface) amino acid residues that are similar to those in EGL-44.

The egl-44 gene produces a single transcript of 2.1 kb (data not shown) with a 5′ SL1 trans-spliced leader (Krause and Hirsh 1987). The level of mRNA from mixed-stage animals compared with that of elongation factor 3 (elf-3) is reduced fivefold in strains with the n998 and n1087 mutations and twofold in a strain with the n1080 mutation (the former mutations also produce a slightly stronger Egl phenotype; Desai and Horvitz 1989). This reduction could result from message instability caused by the egl-44 mutations or could indicate that egl-44 influences its own level.

The egl-44 gene encodes a putative transcription regulatory protein of 471 amino acids similar to transcription enhancer factor (TEF) proteins (Fig. 1). TEF-1 was first cloned from the HeLa cell (Xiao et al. 1991). TEF-1-like proteins, which have been found from yeast to humans, are involved in a variety of developmental processes (e.g., Laloux et al. 1990; Sewall et al. 1990; Campbell et al. 1992; Jiang et al. 1999). For example, mutations in the Drosophila TEF gene scalloped affect the development of sensory bristles and central neurons needed for taste (Campbell et al. 1992), and human TEF-5 is expressed in the placenta and activates the chorionic somatomammotropin gene (Jacquemin et al. 1997; Jiang et al. 1999). The most conserved region among family members is the 70-amino-acid TEA/ATTS DNA-binding domain at the N terminus (Andrianopoulos and Timberlake 1991; Bürglin 1991). EGL-44, the Drosophila TEF Scalloped (Sd), and the human TEF-5 protein (the human TEF most similar to EGL-44) are 82% identical in the TEA/ATTS DNA-binding domain. The egl-44 mutations are in this domain. The C-terminal half of EGL-44, Sd, and TEF-5 are also 47% identical, and this region in TEF-1 contains Pro-rich, STY-rich, and other sequences that are needed together for transcriptional activation (Hwang et al. 1993). Although EGL-44 does not contain sequences that match the activation domains in other TEF proteins, its C-terminal half is rich in Pro, Ser, Thr, and Tyr.

egl-44 is expressed in many cell types

The expression pattern of egl-44 was determined with gfp fusion reporters. A C-terminal GFP fusion (EGL-44::GFP) fluoresced in pharyngeal muscle cells and some intestinal nuclei (data not shown). Because this reporter did not rescue the Egl phenotype, it may not reflect accurately the egl-44 expression pattern. A free C terminus may be important for function, because an N-terminal protein fusion (GFP::EGL-44) partially rescued the Egl phenotype (data not shown), and we believe the pattern of fluorescence is more likely to represent the true expression pattern of the gene. GFP was detected in various nuclei starting from before gastrulation through adulthood (Fig. 2). Newly hatched larvae expressed GFP in nuclei of the hypodermis (hyp3, hyp4, hyp6, and hyp7), intestine, pharyngeal muscle cells, and neurons (in the head and in the ventral, retrovesicular, preanal, and lumbar ganglia). In the second larval stage (L2), more hypodermal nuclei fluoresced in the body and the tail. In adults, GFP fluorescence was much fainter in the hypodermal cells and no longer delectable in some neurons in the head and tail. Other neuronal expression and the intestinal expression remained.

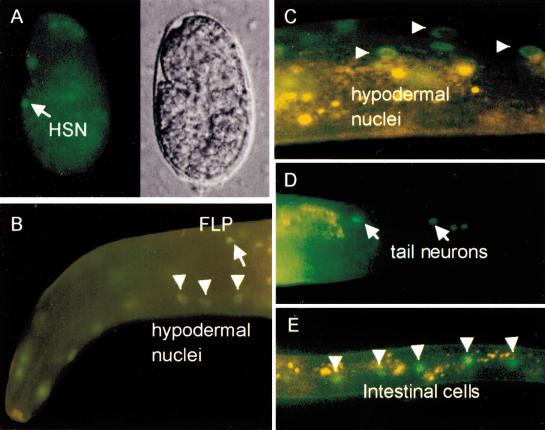

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of gfp::egl-44 (TU#644) in wild-type animals. (A) A 1.5-fold embryo with a fluorescent HSN cell (arrow). (B) An L2 larva with expression in hypodermal nuclei (triangles) and an FLP neuron (arrow). (C) An L4 larva with expression in hypodermal nuclei (triangles). (D) An adult with expression in tail neurons (arrows). (E) An L3 larva with expression in intestinal nuclei (triangles).

GFP::EGL-44 was expressed in two cell types, the FLP and HSN cells, whose cell fate is altered in egl-44 mutants. The fluorescence in the FLP cells was maintained from the L1 larval stage through adulthood. In contrast to the FLP cells, which expressed the fusion postembryonically, the HSN neurons fluoresced only embryonically, at the 1.5-fold stage. We confirmed the identity of these embryonic HSN cells by noting the absence of this fluorescence in egl-1(n487) mutants, animals in which the HSN neurons die at this time.

GFP::EGL-44 expression was not seen in the touch cells. egl-44 mutants, however, have a relatively small number of touch cell defects: A few animals have additional AVM- and PVM-like cells, and the processes of a few of the touch cells are misdirected (Mitani et al. 1993). Presumably, these defects are due to the loss of egl-44 in other cells.

egl-46 defines a new class of zinc finger proteins

Desai and Horvitz (1989) identified four EMS-derived alleles of the egl-46 gene (n1075, n1076, n1126, and n1127) in a screen for animals with defective HSN cells. They also mapped the gene to position 0.13 on chromosome V. We used germ-line transformation to test cosmid clones from this genomic region for their ability to rescue the Egl phenotype of egl-46(n1076) animals. Cosmid CO9E6 and a 5.5-kb EagI–HpaI fragment from it rescued the Egl defect (Table 1 and data not shown). The rescuing fragment is also present in an overlapping cosmid, K11G9, that has been sequenced by the C. elegans Genome Project. The Genome Project predicted only one gene, K11G9.4, on this fragment. Northern blot analysis with an egl-46 cDNA clone revealed only one hybridizing band of approximately 1.6 kb from poly(A)+ RNA from mixed-stage animals (data not shown).

Using the EagI–HpaI rescuing fragment, we obtained and sequenced one cDNA clone from a C. elegans cDNA library (Okkema et al. 1994). We also sequenced an egl-46 cDNA clone, yk268b9 (provided by Y. Kohara) and performed 5′ RACE analysis to determine the complete sequence of the egl-46 message. The egl-46 mRNA is spliced to the SL1 splice leader (Krause and Hirsh 1987) and contains a 774-bp open reading frame and a 569-bp 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The 3′ UTR also contains a consensus polyadenylation site.

All four egl-46 mutant strains contained mutations in the predicted egl-46 gene, K11G9.4 (Fig. 3). egl-46(n1075) contains a small deletion accompanied by a short insertion in the promoter region. Two alleles, n1076 and n1127, have point mutations in splice sites. n1076 contains a G to A mutation in the fifth base of the intron 1 splice donor. Although this position is much less conserved than the first two bases of splice donor sites, a similar mutation in the unc-52 gene also produced a mutant phenotype (Rogalski et al. 1995). n1126 contains a missense mutation in a conserved zinc finger region. Together with the results of the rescue experiments, the sequence of the mutant alleles confirms that K11G9.4 is the egl-46 gene.

Figure 3.

Alignment of EGL-46 with similar proteins from Drosophila and mammals. Four egl-46 mutations are also indicated. (Bars) Nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the three conserved zinc-finger domains; (boxes) additional zinc-finger domains in the mammalian proteins; (triangles) positions of introns; (red typeface) amino acid residues identical to those in EGL-44; (blue typeface) amino acid residues that are similar to those in EGL-44.

egl-46 encodes a predicted protein of 286 amino acids (Fig. 3). The most notable features of EGL-46 are three closely spaced zinc finger motifs in the C-terminal region of EGL-46. The first two zinc finger motifs are separated by 9 amino acids and may form a pair, and the third motif is19 amino acids C-terminal to the first two. The second finger motif of EGL-46 conforms to the TFIIIA (C2H2) consensus (Brown et al. 1985; Miller et al. 1985), whereas the other two fingers differ slightly. In the first and third fingers, the last His is replaced by Cys; in the first finger, the spacing between the His and the last Cys residue differs from the consensus. Nonetheless, the overall spacing and the conservation of other residues indicate that these are variants of the TFIIIA type. These three zinc fingers may mediate DNA binding by egl-46 (for review, see Klug and Schwabe 1995). Consistent with a role in the nucleus, EGL-46 contains a potential nuclear localization signal (amino acids110–126). Also consistent with a role as a transcription factor, EGL-46 contains a glutamine-rich region (amino acids 61–75), which may act as a transcriptional activation domain (Courey and Tjian 1988).

EGL-46 and several proteins with which it shares similarity appear to form a new family of zinc finger proteins. These proteins include the human and mouse IA-1 proteins, the mouse MLT-1 protein, a human protein we are tentatively naming R-355C3p (this represents an intronless coding sequence in clone R-355C3 from chromosome 14 that we identified by a tblastn search of GenBank human genome data), and two proteins from Drosophila melanogaster, Nerfin-1 and Nerfin-2 (Fig. 3; Stivers et al. 2000). No other closely similar sequences are found in the C. elegans genome (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998). All seven proteins have three zinc finger regions; the mammalian proteins have two additional zinc finger sequences C-terminal to these three. The first two zinc fingers show considerable similarity and equal spacing in all seven proteins. The second zinc finger of the pair is 90% identical for all the proteins and has a conserved potential PKC phosphorylation site. The high degree of similarity in this zinc finger pair region indicates that the region is functionally important. The egl-46(n1127) mutation produces a Cys to Phe substitution in the first zinc finger of this pair. All seven proteins share an additional region of similarity N-terminal to the zinc fingers (26 amino acids in EGL-46) that contains a potential nuclear localization signal. N-terminal to this region, all seven proteins have regions that are proline-rich (although EGL-46 is less so than the others). The mammalian proteins also contain a short transcriptional repression domain that Grimes et al. (1996) noted in human IA-1, but this sequence is not conserved in EGL-46 or the Drosophila proteins.

Two features of egl-46 indicate that its product may be regulated posttranscriptionally. First, the N-terminal region of the protein contains a 25-amino-acid putative PEST sequence that could target the protein for rapid degradation (Rogers et al. 1986). Second, the egl-46 mRNA 3′ UTR contains sequences that may target the mRNA for degradation. The 3′ UTR contains three AUUUA motifs, which have been associated with RNA instability (Shaw and Kamen 1986). More recent work, however, has found that a single AUUUA motif is not sufficient to cause mRNA instability and that a UUAUUUA(U/A)(U/A) sequence may be required (Lagnado et al. 1994; Zubiaga et al. 1995). egl-46 has the core of this sequence, UAUUUAU, which when tested in three copies promoted mRNA degradation (Lagnado et al. 1994).

Several other members of this gene family share these features. The Nerfin-1 (but not Nerfin-2), hIA-1 (but not mIA-1), MLT 1, and R-355C3p proteins have predicted PEST sequences. Nerfin-1, hIA-1 (Goto et al. 1992), and mlt 1 mRNAs contain AUUUA repeats in their 3′ UTRs.

Little is known about the EGL-46-related proteins, although they are often found in neuronal tissues, and at least Nerfin-1 and IA-1 are found in dividing neural precursors. Of the Drosophila proteins, Nerfin-1 is distributed widely throughout the nervous system and is observed in many neuronal precursors; Nerfin-2 is found in only a few neurons (Stivers et al. 2000). The human IA-1 protein is found in many neuroendocrine tumor cell lines and virtually all small cell lung cancer cell lines (Lan et al. 1993). The human R-355C3p protein is represented by the zf66e11 EST that was isolated from an adult retina cDNA library (GenBank accession no. AA058826). The mouse protein MLT 1 has been identified in brain and kidney (M. Tateno, pers. comm.).

egl-46 is expressed in neuronal cells

We examined the expression of a gfp::egl-46 protein fusion construct that contained 3 kb of upstream sequence and that rescued the egl-46 mutant phenotype (Fig. 4; data not shown). Fluorescence was first seen in some embryonic cells after gastrulation. As with egl-44 expression, all expression was confined to nuclei. Several cells in the head and tail, most of which appeared to be neuronal, were fluorescent in larvae and adults. The expression in at least some of the cells varied with time.

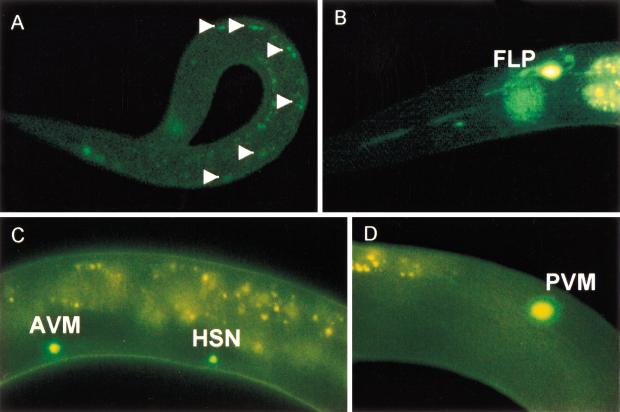

Figure 4.

Expression pattern of gfp::egl-46. (A) An L1 larva with expression in ventral cord motor neurons (arrows). (B) An L2 larva with expression in an FLP neuron. (C) An L2 larva with expression in the AVM and HSN neurons. (D) An L3 larva with expression in a PVM neuron.

We saw the strongest expression and most continuous expression (lasting into the adult) in the FLP cells (Fig. 4), which were identified by their position lateral to the second bulb of the pharynx. We showed the coexpression of egl-44 and egl-46 in the FLP cells by simultaneously introducing yfp::egl-44 and cfp::egl-46 into wild-type animals (data not shown). (A few additional neurons in the head and at least two neurons in the tail also coexpressed these markers.)

Just as with gfp::egl-44 expression, the two HSN cells [absent in egl-1(n487) mutants] were seen in comma-stage to 1.5-fold–stage embryos (Fig. 4). We sometimes saw egl-1(+)-dependent expression in cells in the normal HSN position in L1 and L2 larvae, but never in L3 or older animals.

In addition to these cells, GFP fluorescence was also found in 11 pairs of ventral cord neurons in the late L1 stage but not later. This expression is consistent with the observation that young egl-46 larvae are slightly uncoordinated. As many as 10 cells also fluoresced in the heads of L1 larvae. A few of these cells also expressed gfp::egl-44. One cell in the tail also fluoresced at hatching, and two additional cells fluoresced at the end of the L1 stage and the beginning of the L2 stage. All of these cells lost their fluorescence as the animals matured. (A few of the head neurons and the two later-expressing tail cells also expressed egl-44; data not shown.) Unexpectedly, the touch cells also expressed the gfp::egl-46 fusion (Fig. 4). This expression was transient (mainly in L2 larvae) and much fainter than the expression in the FLP cells (the postembryonically derived AVM and PVM cells fluoresced strongest). Some PVM fluorescence was seen at the L3 stage.

gfp::egl-46 was also expressed in the PVD neurons, a pair of neurons arising postembryonically from the bilateral V5.pa lineages. The V5.pa lineage has some similarities to the Q lineage, one of which is that both generate a neuron that expresses mec-3lacZ: the PVD in the V5.pa lineage and the AVM/PVM in the Q lineage (Way and Chalfie 1989).

We found a similar pattern of expression with Pegl-46gfp, an egl-46 promoter fusion expressing GFP, with the exception that expression lasted much longer. In particular, touch cells, HSN cells, and ventral cord motor neurons all fluoresced in young adults of 12 of 13 independently derived lines (the thirteenth line had weak fluorescence throughout and was difficult to score).

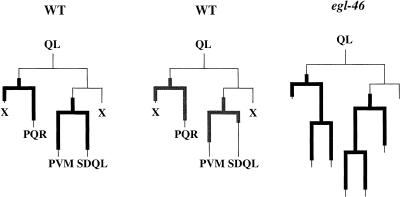

egl-46 is expressed transiently in the Q lineages

Because the lineages of the Q neuroblasts (the precursors of AVM and PVM) have extra terminal divisions in egl-46 mutants (Desai and Horvitz 1989), we examined egl-46 expression in the Q lineages (16 QR lineages and 35 QL lineages) using an egl-46 promoter fusion containing 3 kb of upstream sequence, codons for the first 8 amino acids of EGL-46, and the gfp gene (Fig. 5). In wild-type animals, Pegl-46gfp was expressed in Q.a and its two daughters, one of which undergoes cell death, whereas the other migrates to the head (AQR from QR) or tail (PQR from QL). We did not observe expression in Q.p, but Pegl-46gfp was expressed in Q.pa and its two daughters, the neurons SDQ and AVM/PVM (n = 51). Expression in the postmitotic progeny was not maintained in stages later than L3–L4. These results show that Pegl-46gfp is expressed in the precursors of the cells that undergo extra divisions as well as in the cells that undergo the extra divisions. egl-46 is thus likely to act within the Q lineages to regulate the cell division pattern. We examined Pegl-46gfp expression in an egl-46(n1075) mutant background and found that the cells undergoing extra divisions and their progeny appeared to express the construct (Fig. 5). egl-46 may be necessary for the progeny cells in which it is expressed to exit the cell cycle and undergo differentiation at the correct time.

Figure 5.

egl-46 expression in the QL lineage. Expression from the promoter fusion Pegl-46gfp (thick black lines) or the full-length coding fusion gfp::egl-46 (thick gray lines) is indicated.

Expression of the full-length gfp::egl-46 fusion in the QL lineage was the same as that of the Pegl-46gfp promoter fusion, except that the former was expressed very briefly in the SDQL cell (Fig. 5). All 14 Pegl-46gfp animals with fluorescent PVM cells 11 h after hatching (the cells arise a few hours before this; Sulston and Horvitz 1977) had fluorescent SDQL cells. In contrast, only 1 of 13 gfp::egl-46 11-hour-old larvae with fluorescent PVM cells had a fluorescent SDQL cell (one animal lost the SDQL cell fluorescence while it was being examined). An additional animal appeared to have only an SDQL cell, but it could have been a displaced PVM cell.

To characterize the extra cells generated by the QL lineage in egl-46 mutants, we examined touch cell-specific expression using mec-18::gfp. Four of thirty animals (all L2 stage or older) had an extra fluorescent cell near PVM. We followed 11 QL lineages in L1 animals and found that five had extra cell divisions of QL.pa; the remaining lineages were normal and only the expected expression in QL.paa was seen. The most anterior QL.pa descendant in three of the five unusual lineages (QL.paaa in two cases; QL.paaaa in another) expressed mec-18::gfp (in one of these, the sister cell, QL.paap, also fluoresced). In the two other lineages, a posterior daughter (QL.paaap) fluoresced. Two of six lineages in a strain with mec-3::gfp also had extra divisions. In one lineage, the most anterior QL.pa descendant (QL.paaa) fluoresced; in the other, both QL.paaa and QL.paap fluoresced. We never saw mec-18::gfp in any QL.a descendant (n = 11). Thus, ∼40% of egl-46 mutant animals have lineages with extra divisions, but only 20% of these produced an extra mec-18-expressing cell.

The lineages of the ventral cord neuroblasts, Pn.a, also expressed Pegl-46gfp. The 13 Pn.a neuroblasts arise in the ventral cord in the mid-L1 stage and undergo a characteristic set of divisions (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). We examined the lineages of the Pn.a neuroblasts in the central body region in wild-type animals and found Pegl-46gfp expression in the Pn.aaa cells shortly before their divisions and in their progeny, the VA and VB motor neurons (data not shown). As in the Q lineages, Pegl-46gfp was expressed before the last cell division. Again, the expression in the progeny neurons usually was absent in later stages (L3–adult).

egl-44 and egl-46 act in both the FLP and HSN cells

The coexpression of egl-44 and egl-46 in the FLP and HSN cells indicates that these genes act within these cells to affect their development. To show the requirement for egl-44 and egl-46 expression in these cells, we transformed Pmec-3egl-44 and Pmec-3egl-46 into egl-44 and egl-46 mutants, respectively, and found that these FLP-expressing constructs repressed mec-18::gfp expression in the FLP cells (Table 1). We also expressed egl-44 and egl-46 individually in the FLP and HSN cells (and others) using a 5.1-kb unc-86 promoter (Baumeister et al. 1996). The resulting animals had reduced FLP expression of mec-18::gfp and a reduction in the HSN-dependent egg-laying defect compared with the control injected mutants (Table 1).

egl-44 is needed for normal egl-46 expression in the FLP cells

FLP expression of gfp::egl-46 was very weak or undetectable in animals with the egl-44(n998) loss-of-function mutation (Fig. 6); the expression in other neurons, such as AVM, PVM, and HSN cells was similar to that seen in wild-type animals. When we crossed two egl-44(n998) lines containing extrachromosomal gfp::egl-46 arrays with wild-type males, the resulting egl-44(n998)/+ heterozygotes regained the bright fluorescence in the FLP neurons (again, no other changes were seen). In addition, the level of egl-46 mRNA in egl-44(n998) mutants was four- to fivefold lower than in wild type (data not shown). (Even though GFP::EGL-46 is expressed in several cells, the GFP fluorescence expression is most intense and lasts longest in the FLP cells. The reduction in mRNA, thus, probably reflects the loss of FLP expression.) These observations indicate that egl-44 is needed for sufficient and persistent egl-46 expression in FLP cells.

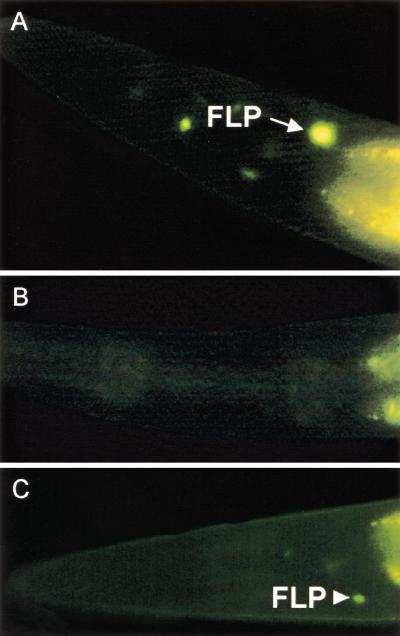

Figure 6.

egl-44 is important for egl-46 expression in FLP neurons. (A) Strong GFP fluorescence from gfp::egl-46 in a wild-type FLP cell. (B) Absence of fluorescence in an egl-44 mutant. (C) Faint fluorescence from an FLP cell in an egl-44 animal. All animals are L3 larvae.

Consistent with these findings, coexpression of gfp::egl-46 and Pmec-3egl-44 caused prolonged expression of GFP in the touch cells. Fluorescence was not noticeably greater in touch cells at early larval stages, but it was seen in all six touch cells in 60% of the adults from three of four lines (12/20, 12/20, 13/20, and 4/20). This latter expression was never seen with gfp::egl-46 alone (11 lines). Moreover, when gfp::egl-46 was coexpressed with Pmec-7egl-44(R125Q), which has the same mutation as egl-44(n998 and n1087), only 1 adult in 20 from three lines had any touch cell fluorescence (no adults from five other lines had touch cell fluorescence). When Pmec-3egl-44(R125Q) was used, only two of six lines showed a few fluorescent touch cells in adults (3/20, 4/20), and this fluorescence was much fainter than that of the FLP cells. Thus, egl-44 is needed for prolonged expression of egl-46 in the touch cells.

In contrast, no differences in gfp::egl-44 expression or egl-44 transcript level were seen in the egl-46(n1075) mutant background when compared with wild type (data not shown). Thus, egl-44 seems to act upstream of egl-46 in the negative regulation of touch cell fate in FLP neurons by initiating and/or maintaining egl-46 expression.

Ectopic egl-44 and egl-46 together repress touch cell differentiation

Because mutation of either egl-44 or egl-46 alters the fate of the FLP cells (Mitani et al. 1993) and because gfp::egl-46 was expressed in at least some of the touch cells, neither gene is likely on its own to prevent touch cell fate. To test further how these genes prevent touch cell fate, we expressed them ectopically in the touch cells using mec-7 and mec-3 regulatory sequences in a strain containing an integrated array of mec-18::gfp and examined the resulting animals for touch sensitivity and mec-18::gfp expression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ectopic expression of egl-44 and egl-46 in the touch cells

| DNA arraya

|

Background

|

Markerb

|

Lines

|

% Touch-sensitivec

|

% Cells expressing GFPd

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALM

|

AVM

|

PLM

|

PVM

|

|||||

| Control | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | 98 ± 2 | 98 ± 1 | 94 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 | 95 ± 3 |

| Pmec-3egl-46 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | 94 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 | 94 ± 10 | 100 ± 0 | 97 ± 5 |

| Pmec-7egl-46 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | 98 ± 1 | 88 ± 3 | 91 ± 2 | 100 ± 0 | 96 ± 1 |

| Pmec-3egl-44e | Wild type | Pmec-3gfp | 4 | N.D. | 95 ± 2 | 97 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 | 100 ± 1 |

| Pmec-7egl-44e | Wild type | Pmec-3gfp | 4 | N.D. | 97 ± 2 | 95 ± 3 | 100 ± 0 | 97 ± 4 |

| Pmec-3egl-44 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | 61 ± 5* | 32 ± 7** | 28 ± 6** | 54 ± 5* | 68 ± 6 |

| Pmec-7egl-44 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4f | 70 ± 5* | 73 ± 7 | 72 ± 6* | 79 ± 2* | 72 ± 8 |

| Pmec-7egl-44 | egl-46(n1075)/+g | Pmec-7gfp | 4 | 45 ± 6* | 47 ± 6** | 29 ± 4** | N.D. | 44 ± 2** |

| Pmec-7egl-44 | egl-46(n1075) | Pmec-7gfp | 4 | 90 ± 3 | 85 ± 5 | 70 ± 4* | N.D. | 78 ± 3 |

| Pmec-3egl-44(R125Q) | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | N.D. | 91 ± 4 | 93 ± 4 | 84 ± 7 | 97 ± 6 |

| Pmec-7egl-44(R125Q) | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 5 | 98 ± 1 | 95 ± 2 | 94 ± 3 | 97 ± 2 | 95 ± 2 |

| Pmec-7egl-44(R125Q) | egl-46(n1075)/+g | Pmec-7gfp | 4 | 97 ± 1 | 89 ± 5 | 90 ± 3 | N.D. | 97 ± 0 |

| Pmec-7egl-44(R125Q) | egl-46(n1075) | Pmec-7gfp | 4 | 98 ± 1 | 82 ± 5 | 87 ± 2 | N.D. | 94 ± 3 |

| Pmec-3egl-44+Pmec-3egl-46 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 4 | 58 ± 7* | 31 ± 6** | 25 ± 10** | 31 ± 7** | 54 ± 8* |

| Pmec-7egl-44+Pmec-7egl-46 | Wild type | mec-18::gfp | 3f | 55 ± 6* | 30 ± 10** | 59 ± 3* | 41 ± 5** | 60 ± 10 |

All animals were injected with the pRF4 plasmid. All DNA arrays were extrachromosomal.

All of the markers except Pmec-7gfp were integrated transgenes.

Animals that responded to at least 5 of 10 touches were classed as touch-sensitive; in comparison, no mec-3 and mec-7 loss-of-function mutants respond to such stimuli. (N.D.) not determined. Significance was determined with the t-test (*) P < 0.01; (**) P < 0.001.

Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M. We examined 50–120 animals from each line. Because Pmec-7gfp was expressed in at least four cells in the tail, we did not determine whether the PLM cells were present in animals containing this marker. Statistics as in the previous note.

Ninety-seven percent of these animals had fluorescent FLP cells.

For each of these strains, one additional line showed no reduction in mec-18::gfp expression; because it presumably did not express the egl-44 transgene, its data were not included.

These animals were derived from those directly below them in the table by crossing the latter animals with wild-type males.

Expression of Pmec-7egl-46 in the touch cells, as expected, did not alter touch sensitivity or mec-18::gfp expression. In contrast, when both Pmec-7egl-44 and Pmec-7egl-46 or Pmec-7egl-44 alone were introduced into otherwise wild-type touch cells, the animals became significantly less touch-sensitive and had reduced mec-18::gfp expression (Table 2). The additional egl-46 activity provided by the extragenic array in the former case may explain why touch sensitivity and mec-18::gfp expression decreased slightly more dramatically than with egl-44 alone (Table 2). The effects on the touch cells were not caused by the extragenic mec-7 promoter competing for touch cell regulators such as mec-3 and unc-86, because the introduction of Pmec-7egl-44(R125Q), which produces nonfunctional EGL-44, did not alter touch sensitivity or mec-18::gfp expression.

Because the mec-7 promoter could be a direct target of EGL-44 or/and EGL-46, the previous results may not show the full effect of expression of these genes because of possible negative feedback. To avoid this difficulty, we performed similar experiments with mec-3 promoter constructs. The Pmec-3 constructs gave a similar, if not a bit greater, reduction in touch cell expression of mec-18::gfp (Table 2) and a similar loss of touch sensitivity (data not shown).

To confirm that the combined action of both genes repressed touch cell fate, we introduced Pmec-7egl-44 and Pmec-3egl-44 individually into animals with the loss-of-function mutation egl-46(n1075) (Table 2). A slight reduction of touch sensitivity and extrachromosomal Pmec-7gfp expression was seen, indicating that although both genes are needed for significant reduction in touch cell fate, egl-44 alone may slightly affect touch cell fate. When both strains were crossed with wild-type males, we saw a much more dramatic drop in the touch sensitivity and extrachromosomal Pmec-7gfp expression in the resulting egl-46(n1075)/+ progeny (Table 2). Again, the nonfunctional egl-44(R125Q) constructs did not affect touch cell differentiation in these experiments. The repressive effect of egl-44 and egl-46 is downstream from mec-3 expression, as mec-3::gfp expression was not detectably altered by either Pmec7egl-44 or Pmec-3egl-44 (Table 2). Taken together, the expression of egl-44 and egl-46 genes in the touch cells shows that neither gene alone is capable of repressing touch cell fate sufficiently and both are necessary to repress the touch cell differentiation.

Discussion

egl-44 and egl-46 encode putative transcription factors

Much of the development of the touch cells and of the HSN neurons of C. elegans is regulated at the level of transcription. Touch cell development requires the basic helix-loop-helix protein LIN-32 and the homeodomain proteins UNC-86 and MEC-3 (Chalfie and Sulston 1981; Finney et al. 1988; Way and Chalfie 1988; Chalfie and Au 1989; Zhao and Emmons 1995), whereas the HSN development requires UNC-86 and the zinc finger protein SEM-4 (Desai et al. 1988; Basson and Horvitz 1996). Our finding that egl-44 and egl-46 encode putative transcription factors (a TEF protein and a zinc finger protein, respectively) is consistent with the idea that transcriptional control is a major determinant of neuronal cell fate in C. elegans.

TEF proteins, which are found from yeast to mammals, play important roles in cardiogenesis, myogenesis, neural development, and organogenesis (Xiao et al. 1991; Campbell et al. 1992; Chen et al. 1994). The role of egl-44 in C. elegans cell differentiation is consistent with these functions in other organisms. Consistent with the observation that wild-type egl-44 promotes HSN development and prevents touch cell differentiation in the FLP cells, at least some TEF proteins can activate as well as repress transcription (Xiao et al. 1991; Jiang et al. 1996; Yockey et al. 1996). The requirement for both egl-44 and egl-46 to repress touch cell differentiation in the FLP cells is also consistent with the finding that TEF proteins interact with several different proteins (Jiang and Eberhardt 1996; Gupta et al. 1997; Halder et al. 1998; Paumard-Rigal et al. 1998; Simmonds et al. 1998) including the zinc finger protein poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (Butler and Ordahl 1999).

Because egl-44, the only C. elegans TEF gene, is expressed in several cells that do not detectably express egl-46, EGL-44 may act with other factors. In addition, although both genes are needed for HSN development, the differential timing of their expression hints that they may act with other proteins in these cells. We and others (Desai et al. 1988; Desai and Horvitz 1989; Mitani et al. 1993), however, have not identified phenotypes in egl-44 animals not seen in egl-46 animals that would indicate egl-46-independent functions for egl-44.

EGL-46, the Drosophila Nerfins, and the mammalian IA-1 and MLT 1 proteins form a new family of TFIIIA-like zinc finger proteins. Although zinc fingers can serve as protein–protein interaction domains (for review, see Mackay and Crossley 1998), the presence of multiple TFIIIA-type fingers is correlated with nucleic acid binding (Klug and Schwabe 1995), indicating that these proteins act as transcription factors. These genes are all expressed in the nervous system, the worm and fly genes exclusively so.

In addition to the cell differentiation phenotypes displayed by egl-44 mutants, egl-46 mutants also have defects in the Q cell lineages (Desai et al. 1988; Desai and Horvitz 1989; Mitani et al. 1993). In these lineages and in the lineages of the ventral cord precursors, egl-46 expression appears to mark the transition from the cell division to differentiation stage. In these lineages, egl-46::gfp is expressed in neural precursors shortly before they divide to produce two postmitotic neurons, which also express the reporter early in their development. Loss of egl-46 function in the Q lineages (but not in the ventral cord lineages) results in the production of additional cells through extra rounds of cell division. All of these cells continue to express egl-46. This continued expression may be caused by an alteration of fates, such that cells that would normally undergo terminal differentiation assume the fates of precursor cells that divide; for example, Q.paa may assume the fate of Q.pa. Alternatively, cell fates may be unaltered in egl-46 mutant animals, but some cells may be blocked in their ability to undergo a normal terminal differentiation program involving exit from the cell cycle.

The egl-46 expression pattern is dynamic and is usually not maintained. Because gfp expression from the egl-46 promoter does not seem to be different in an egl-46 mutant background, the gene probably does not repress its own transcription. Expression of the full-length gfp::egl-46 reporter, however, was much briefer than that of the promoter fusion, indicating that egl-46 may be regulated posttranscriptionally. The EGL-46 PEST sequence and the 3′ UTR sequences may explain, at least in part, the more rapid elimination of GFP fluorescence from the SDQL and PVM cells seen with protein fusions compared with promoter fusions.

An intriguing difference is seen in gfp::egl-46 expression when the Q.pa cell divides to produce the PVM and SDQL cells. Expression in SDQL goes away soon after the cell division, whereas expression in PVM is maintained for several hours. This relatively prolonged expression may indicate that egl-46 functions, perhaps redundantly, in PVM differentiation.

Negative regulation of touch cell fate

egl-44 appears to repress the expression of touch cell features in the FLP cells in two ways. First, egl-44 is required for the wild-type levels of egl-46 expression in these neurons. Second, egl-44 must be expressed with egl-46 to repress touch cell differentiation. This conclusion is supported by the ectopic expression of these genes in the touch cells and by the finding that these cells normally express egl-46. (The expression of egl-46 in the touch cells may account for the minor touch cell process and morphological defects in egl-46 mutants.) EGL-44 may interact directly with EGL-46, because, as mentioned above, TEF proteins in other organisms act as transcription cofactors.

These considerations extend the model of combinatorial control of touch cell development (Fig. 7). In the six touch cells, unc-86 promotes mec-3 expression, and the UNC-86/MEC-3 heterodimer activates the expression of touch genes. In the FLP neurons, egl-44 promotes egl-46 expression, presumably with some other factor(s), and EGL-44 and EGL-46 together, presumably also with some other factor(s), inhibit touch gene expression to secure the normal differentiation of FLP neurons. Because mec-3 and unc-86 are expressed in FLP cells normally, it is possible that EGL-44 and EGL-46 repress touch cell fate by directly antagonizing activation by MEC-3 or/and UNC-86.

Figure 7.

Model for the determination of touch cell fate. The complex of UNC-86 and MEC-3 activates (arrows) expression from touch cell-specific genes in the six touch receptor neurons. In the FLP cells, the action of these positive regulators is prevented (⊣) by the action of EGL-44 and EGL-46. In addition, EGL-44 regulates the expression of EGL-46 (short arrow).

The roles of egl-44 and egl-46 in HSN development

Although both egl-44 and egl-46 are expressed in the HSN neurons, and expression of the wild-type genes in the HSN cells complements egl-44 and egl-46 mutations, the timing of their expression is unexpected given the phenotypes of the mutant cells. egl-44 and egl-46 mutations affect HSN differentiation in three ways: The cells migrate further than wild-type cells, their axons are misdirected, and they have reduced production of the neurotransmitter serotonin (Desai et al. 1988; Desai and Horvitz 1989). Of these three processes, only cell migration occurs in the embryos; the others arise as the animals become adults. In contrast, the HSN cells express egl-44 in the embryo and express egl-46 in the embryo and transiently and weakly in L2 larvae. The embryonic expression could underlie a role for these genes in the regulation of HSN migration. The expression pattern of these genes is less easily reconciled with the late larval outgrowth defects and adult serotonin defect (both of which are incompletely penetrant). One explanation is that these genes act early to establish the ability of the cells to generate serotonin or grow appropriately. If so, the genes could act indirectly within the HSN to influence these later traits. C. Desai and H.R. Horvitz (pers. comm.), for example, have suggested that interactions of the HSN cells with their muscle targets result in the lowered levels of serotonin in the mutant HSN cells. An early defect in the HSN cells could lead to these abnormal interactions. Alternatively, because the genes are expressed in many other cells, their influence on axonal outgrowth and/or serotonin production could be caused by the loss of gene activity in other cells; i.e., some of the HSN phenotypes are not the result of the cell-autonomous action of the genes. The AVM and PVM touch cells also have a low penetrant outgrowth defect in egl-44 and egl-46 animals (Mitani et al. 1993), but the cells do not detectably express egl-44. Perhaps the loss of egl-44 expression in the hypodermis underlies the touch cell and HSN outgrowth defects.

Materials and methods

General methods and strains

C. elegans strains were cultivated at 20°C as described by Brenner (1974). In addition to wild type (N2), the following mutant strains were used: LGII: MT2071[egl-44(n998)], MT2247[egl-44(n1080)], MT2254[egl-44(n1087)], TU2673[egl-44(n998) outcrossed four times], TU2672[egl-44(n1087) outcrossed four times]; LGV: MT2242[egl-46(n1075)], MT2243[egl-46(n1076)], MT2315[egl-46(n1126)], and MT2316[egl-46(n1127)]; TU2583 [uIs25 (an integrated Pmec-18gfp array)], TU2678 [uIs25;egl-44(n998)], and TU2679 [uIs25;egl-46(n1075)]. TU2562 contains uIs22 (an integrated Pmec-3gfp array) that has not been mapped.

Germ line transformation

Cosmids covering the previously mapped positions of egl-44 and egl-46 (kindly provided by A. Coulson) were injected with the dominant rol-6(su1006) marker plasmid pRF4 using standard methods (Mello et al. 1991). The rescue of the Egl phenotype was determined in transgenic animals after the onset of egg laying by looking for animals that did not retain late-stage eggs. The DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using a polymerase mix suitable for long-range PCR (Clontech), and appropriate primers and the PCR products were subcloned using the TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen).

Sequencing of mutant alleles

The egl-44 gene was amplified from the three mutant strains by single-worm PCR (Williams 1995). The PCR products were sequenced using the Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Sequencing Kit (US Biochemical). The egl-46 gene was amplified from genomic DNA preparations of the four mutant strains and subcloned using the TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). DNA was sequenced by the DNA Facility at Columbia University. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing two independently amplified PCR products.

Transcript analysis

We completely sequenced the insert of the one cDNA clone corresponding to egl-44 transcript that was reported in the C. elegans EST collection (yk143c4; Y. Kohara, pers. comm.). This clone contains the full-length egl-44 cDNA starting at the second nucleotide of the first codon. The 5′ end of the egl-44 transcript was determined by sequencing the PCR product generated from an N2 cDNA library using an SL1 primer and an internal primer.

We screened a C. elegans cDNA library (Okkema et al. 1994) with a 5.5-kb egl-46 genomic fragment. We determined the 5′ end of the egl-46 transcript by 5′ RACE analysis using the Amplifinder RACE Kit (Clontech). Fourteen egl-46 RACE products were sequenced, and the three longest contained 6 bp of the SL1 splice start site. Subsequently, three cDNA clones corresponding to the egl-46 mRNA were reported by Y. Kohara. We completely sequenced the insert of one of them, yk268b9.

RNA was obtained from mixed-stage N2, egl-44, and egl-46 animals used to prepare mRNAs using the PolyATtract mRNA isolation system IV (Promega). The 2.1-kb egl-44 cDNA and a 700-bp egl-46 cDNA fragment were used to probe the Northern blots, respectively. An elongation factor 3 (elf-3) cDNA fragment (provided by Victor Ambros) was used as a control in all Northern blots.

Analysis of the expression of reporter constructs

All reporter constructs were coinjected with the dominant marker pRF4. These constructs include: egl-44::gfp (TU#622): A 5.9-kb egl-44 genomic fragment was subcloned in pPD95.57 using its PstI and BamHI sites. The resulting construct has 1.9 kb of egl-44 5′ sequence and coding sequence for full-length EGL-44 fused at its C terminus to GFP.

gfp::egl-44 (TU#625): An ApaI site was introduced into the first exon of egl-44 genomic sequence by PCR mutagenesis. A 1.0-kb gfp fragment was removed from pPD102.33 with ApaI and subcloned into the ApaI site of the egl-44 fragment in pcr2.1 (Invitrogen). GFP was fused to the N terminus of full-length EGL-44. This construct contains 3.1 kb 5′ and 600 bp 3′ of the coding region of egl-44. A similar expression pattern was seen with TU#644, which contained only 1.9 kb of 5′ sequence (this construct rescued less well, however).

Pegl-46gfp (TU#307): A 3-kb egl-46 genomic fragment was inserted into pPD95.75. This construct contains 3 kb of egl-46 upstream sequence and codes for a fusion of the first 8 amino acids of EGL-46 to GFP.

gfp::egl-46 (TU#626): An ApaI site was introduced into the first exon of the egl-46 genomic sequence by PCR mutagenesis. A1.0-kb gfp ApaI fragment from pPD118.85 was subcloned into the ApaI site. This resulting plasmid had 3.0 kb of egl-46 upstream sequence and coding sequence with GFP fused to the N terminus of full-length EGL-46.

cfp::egl-46 (TU#627) and yfp::egl-44 (TU#628): cfp and yfp genes (Miller et al. 1999) were amplified by PCR from the Fire vectors pPD136.61 and pPD136.64, respectively, with one ApaI site at each end. The PCR product was then digested and inserted between the two ApaI sites in TU#626 and TU#623.

Ectopic expression of egl-44 and egl-46

Pmec-7egl-44 (TU#629) and Pmec-7egl-46 (TU#630): egl-44 and egl-46 genomic fragments from start codons to immediately before the stop codons were amplified by PCR from the cosmids containing these genes, respectively, and inserted individually into the SmaI site of pPD96.41. The resulting construct contains about 700 bp of mec-7 upstream regulatory sequence; only 260 bp are needed for touch cell expression (Duggan et al. 1998).

Pmec-3egl-44 (TU#631) and Pmec-3egl-46 (TU#632): egl-44 and egl-46 genomic fragments amplified above were inserted into the SmaI site of pPD57.56, individually. The resulting construct contains 900 bp of mec-3 upstream regulatory sequence, which is sufficient for expression in the touch cells, the FLP cells, and the PVD cells (Way and Chalfie 1989).

Punc-86egl-44 (TU#633) and Punc-86egl-46 (TU#634): egl-44 and egl-46 genomic fragments from the start codons to immediately before the stop codons were amplified by PCR with one ClaI site on the 5′ end and one SpeI site on the 3′ end from the cosmids containing these genes, respectively. The PCR products were then digested and inserted between the ClaI site and the SpeI site in an unc-86 promoter-containing vector pSA2Δ kindly provided by Ji Ying Sze.

We monitored touch cell differentiation using GFP fluorescence produced from several constructs with touch cell promoters (S. Luo, G. Gu, and M. Chalfie, unpubl.). Pmec-3gfp has the mec-3 upstream regulatory sequences plus part of mec-3 coding sequence fused to the coding sequence of GFP. Pmec-7gfp has mec-7 upstream regulatory sequence plus the first two exons of the gene fused to the coding sequence of GFP. mec-18::gfp has the mec-18 upstream regulatory sequences plus almost all of the mec-18 coding sequence fused to the coding sequence of GFP.

Touch-sensitivity assay

Touch sensitivity was assessed as modified from Hobert et al. (1999). Each animal was touched 10 times alternately at the head and tail with an eyebrow hair (between 40 and 130 animals were examined for each line). Animals that responded to at least five touches were classified as touch-sensitive.

Examination of cell lineages

Cell lineages were followed as described by Sulston and Horvitz (1977). For some experiments, animals were synchronized at hatching by treating adults with an alkaline hypochlorite solution and collecting the resulting progeny in M9 buffer overnight (Sulston and Hodgkin 1988).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ward Odenwald for information about the Nerfin proteins before their publication and to the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for mutant strains. This work was supported by NIH grant GM30997 to M.C.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL mc21@columbia.edu; FAX (212) 865-8246.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.857401.

References

- Andrianopoulos A, Timberlake WE. ATTS, a new and conserved DNA binding domain. Plant Cell. 1991;3:747–748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.8.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson M, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene sem-4 controls neuronal and mesodermal cell development and encodes a zinc finger protein. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1953–1965. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. Lineage-specific regulators couple cell lineage asymmetry to the transcription of the C. elegans POU gene unc-86 during neurogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1395–1410. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RS, Sander C, Argos P. The primary structure of transcription factor TFIIIA has 12 consecutive repeats. FEBS Lett. 1985;186:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürglin TR. The TEA domain: A novel, highly conserved DNA-binding motif. Cell. 1991;66:11–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90132-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AJ, Ordahl CP. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase binds with transcription enhancer factor 1 to MCAT1 elements to regulate muscle-specific transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:296–306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S, Inamdar M, Rodrigues V, Raghavan V, Palazzolo M, Chovnick A. The scalloped gene encodes a novel, evolutionarily conserved transcription factor required for sensory organ differentiation in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:367–379. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Au M. Genetic control of differentiation of the Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons. Science. 1989;243:1027–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.2646709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Sulston J. Development genetics of the mechanosensory neurons of C. elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;82:358–370. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Friedrich GA, Soriano P. Transcriptional enhancer factor 1 disruption by a retroviral gene trap leads to heart defects and embryonic lethality in mice. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2293–2301. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Horvitz R. The C. elegans protein EGL-1 is required for programmed cell death and interacts with the Bcl-2-like protein CED-9. Cell. 1998;93:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courey AJ, Tjian R. Analysis of Sp1 in vivo reveals multiple transcriptional domains, including a novel glutamine-rich activation motif. Cell. 1988;55:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans mutants defective in the functioning of the motor neurons responsible for egg laying. Genetics. 1989;121:703–721. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.4.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C, Garriga G, McIntire S L, Horvitz HR. A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature. 1988;336:638–646. doi: 10.1038/336638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll M, Chalfie M. The mec-4 gene is a member of a family of Caenorhabditis elegans genes that can mutate to induce neuronal degeneration. Nature. 1991;349:588–593. doi: 10.1038/349588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan A, Ma C, Chalfie M. Regulation of touch receptor differentiation by the Caenorhabditis elegans mec-3 and unc-86 genes. Development. 1998;125:4107–4119. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney M, Ruvkun G. The unc-86 gene product couples cell lineage and cell identity in C. elegans. Cell. 1990;63:895–905. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney M, Ruvkun G, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell lineage and differentiation gene unc-86 encodes a protein with a homeodomain and extended similarity to transcription factors. Cell. 1988;55:757–769. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, De Silva MG, Toscani A, Prabhakar BS, Notkins AL, Lan MS. A novel human insulinoma-associated cDNA, IA-1, encodes a protein with “zinc-finger” DNA-binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15252–15257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes HL, Chan TO, Zweidler-McKay PA, Tong B, Tsichlis PN. The Gfi-1 proto-oncoprotein contains a novel transcriptional repressor domain, SNAG, and inhibits G1 arrest induced by interleukin-2 withdrawal. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6263–6272. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MP, Amin CS, Gupta M, Hay N, Zak R. Transcription enhancer factor 1 interacts with a basic helix-loop-helix zipper protein, Max, for positive regulation of cardiac α-myosin heavy-chain gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3924–3936. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Polaczyk P, Kraus ME, Hudson A, Kim J, Laughon A, Carroll S. The Vestigial and Scalloped proteins act together to directly regulate wing-specific gene expression in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3900–3909. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O, Moerman DG, Clark KA, Beckerle MC, Ruvkun G. A conserved LIM protein that affects muscular adherens junction integrity and mechanosensory function in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:45–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JJ, Chambon P, Davidson I. Characterization of the transcription activation function and the DNA binding domain of transcriptional enhancer factor-1. EMBO J. 1993;12:2337–2348. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin P, Martial JA, Davidson I. Human TEF-5 is preferentially expressed in placenta and binds to multiple functional elements of the human chorionic somatomammotropin-B gene enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12928–12937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SW, Eberhardt NL. TEF-1 transrepression in BeWo cells is mediated through interactions with the DATA-binding protein, TBP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9510–9518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SW, Wu K, Eberhardt NL. Human placental TEF-5 transactivates the human chorionic somatomammotropin gene enhancer. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:879–889. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JM, Horvitz HR. A dual mechanosensory and chemosensory neuron in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:2227–2231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug A, Schwabe JW. Protein motifs 5. Zinc fingers. FASEB J. 1995;9:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M, Hirsh D. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;49:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagnado CA, Brown CY, Goodall GJ. AUUUA is not sufficient to promote poly(A) shortening and degradation of an mRNA: The functional sequence within AU-rich elements may be UUAUUUA(U/A)(U/A) Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:798479–798495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloux I, Dubois E, Dewerchin M, Jacobs E. TEC-1, a gene involved in the activation of Ty1 and Ty1-mediated gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Cloning and molecular analysis. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3541–3550. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan MS, Russell EK, Lu J, Johnson BE, Notkins AL. IA-1, a new marker for neuroendocrine differentiation in human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4169–4171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay JP, Crossley M. Zinc fingers are sticking together. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcom D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, III, Desai NS, Hardin DC, Piston DW, Patterson GH, Fleenor J, Xu S, Fire A. Two-color GFP expression system for C. elegans. BioTechniques. 1999;26:914–921. doi: 10.2144/99265rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, McLachlan AD, Klug A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985;4:1609–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani S, Du H, Hall DH, Driscoll M, Chalfie M. Combinatorial control of touch receptor neuron expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1993;119:773–783. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okkema PG, Ha E, Haun C, Chen W, Fire A. The Caenorhabditis elegans NK-2 class homeoprotein CEH-22 is involved in combinatorial activation of gene expression in pharyngeal muscle. Development. 1994;120:2175–2186. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paumard-Rigal S, Zider A, Vaudin P, Silber J. Specific interactions between vestigial and scalloped are required to promote wing tissue proliferation in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:440–446. doi: 10.1007/s004270050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski TM, Gilchrist EJ, Mullen GP, Moerman DG. Mutations in the unc-52 gene responsible for body wall muscle defects in adult Caenorhabditis elegans are located in alternatively spliced exons. Genetics. 1995;139:159–169. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: The PEST hypothesis. Science. 1986;234:364–368. doi: 10.1126/science.2876518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G, Giusto J. The Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-14 encodes a nuclear protein that forms a temporal developmental switch. Nature. 1989;338:313–319. doi: 10.1038/338313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage C, Hamelin M, Culotti JG, Coulson A, Albertson DG, Chalfie M. mec-7 is a β-tubulin gene required for the production of 15-protofilament microtubules in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:870–881. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage C, Xue Y, Mitani S, Hall D, Zakhary R, Chalfie M. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans β-tubulin gene mec-7: Effects on microtubule assembly and stability and on tubulin autoregulation. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2165–2175. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.8.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewall TC, Mims CW, Timberlake WE. abaA controls phialide differentiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Plant Cell. 1990;2:731–739. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.8.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw G, Kamen R. A conserved AU sequence from the 3′ untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell. 1986;46:659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds AJ, Liu X, Soanes KH, Krause HM, Irvine KD, Bell JB. Molecular interactions between Vestigial and Scalloped promote wing formation in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3815–3820. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stivers C, Brody T, Kuzin A, Odenwald WF. Nerfin-1 and -2, novel Drosophila Zn-finger genes expressed in the developing nervous system. Mech Develop. 2000;97:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, editor. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way JC, Chalfie M. mec-3, a homeobox-containing gene that specifies differentiation of the touch receptor neurons in C. elegans. Cell. 1988;54:5–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The mec-3 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans requires its own product for maintained expression and is expressed in three neuronal cell types. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:1823–1833. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. Genetic mapping with polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. Meth Cell Biol. 1995;48:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao JH, Davidson I, Matthes H, Garnier JM, Chambon P. Cloning, expression, and transcriptional properties of the human enhancer factor TEF-1. Cell. 1991;65:551–568. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90088-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Finney M, Ruvkun G, Chalfie M. Regulation of the mec-3 gene by the C. elegans homeoproteins UNC-86 and MEC-3. EMBO J. 1992;11:4969–4979. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Tu Y, Chalfie M. Cooperative interactions between the Caenorhabditis elegans homeoproteins UNC-86 and MEC-3. Science. 1993;261:1324–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.8103239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yockey CE, Smith G, Izumo S, Shimizu N. cDNA cloning and characterization of murine transcriptional enhancer factor-1-related protein 1, a transcription factor that binds to the M-CAT motif. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3727–3736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Emmons SW. A transcription factor controlling development of peripheral sense organs in C. elegans. Nature. 1995;373:74–78. doi: 10.1038/373074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubiaga AM, Belasco JG, Greenberg ME. The nonamer UUAUUUAUU is the key AU-rich sequence motif that mediates mRNA degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2219–2230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]