Abstract

Gammaherpesvirus-associated neoplasms include tumors of lymphocytes, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells (ECs). We previously showed that, unlike most cell types, ECs survive productive gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) infection and achieve anchorage-independent growth, providing a cellular reservoir for viral persistence. Here, we demonstrated autophagy in infected ECs by analysis of LC3 localization and protein modification and that infected ECs progress through the autophagosome pathway by LC3 dual fluorescence and p62 analysis. We demonstrate that pharmacologic autophagy induction results in increased survival of infected ECs and, conversely, that autophagy inhibition results in death of infected EC survivors. Furthermore, we identified two viral oncogenes, v-cyclin and v-Bcl2, that are critical to EC survival and that modify EC proliferation and survival during infection-induced autophagy. We found that these viral oncogenes can also facilitate survival of substrate detachment in the absence of viral infection. Autophagy affords cells the opportunity to recover from stressful conditions, and consistent with this, the altered phenotype of surviving infected ECs was reversible. Finally, we demonstrated that knockdown of critical autophagy genes completely abrogated EC survival. This study reveals a viral mechanism which usurps the autophagic machinery to promote viral persistence within nonadherent ECs, with the potential for recovery of infected ECs at a distant site upon disruption of virus replication.

INTRODUCTION

Gammaherpesviruses (γHVs) establish and maintain a quiescent, latent infection for the lifetime of a healthy host. However, in the context of immunodeficiency, γHVs can cause tumors of lymphocytes, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells (ECs). Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) is a natural pathogen of murid rodents and provides a small-animal model for studying the pathogenesis of γHVs (1, 11, 61, 62, 68).

Recently, we reported that in contrast to fibroblasts, which are rapidly lysed during γHV68 infection, ECs support a persistent γHV68 infection, remaining viable and productively infected for a prolonged period of time (63). EC survival in the context of productive and ongoing virus replication is unique and differs from survival of latently infected cells, which also remain viable but do not support ongoing virus replication and production. Striking features of this survival outcome are that ECs are altered in morphology and surface protein expression and lose anchorage dependence. Not only do surviving ECs support robust virus replication, but their unique survival outcome also requires viral DNA amplification and late gene synthesis. While surviving ECs remain viable and release new infectious virus for a prolonged period of time, their eventual fate is cell death.

Several γHV-encoded oncogenes, which are critical for chronic infection, are mimics of host cellular proteins. The proproliferative γHV68 homolog of D-type cyclins is transforming in primary T lymphocytes, is essential for efficient reactivation from latency, and is required for γHV68-associated lymphoproliferative disease and acute pneumonia in immunodeficient mouse models (36, 65, 69, 71). With regard to persistent EC survival of infection, the number of surviving cells is greatly reduced in the absence of the viral cyclin (v-cyclin), while the amount of virus produced per cell is unaffected (63). γHV68 also encodes an antiapoptotic v-Bcl2 protein, referred to as M11, which is homologous to cellular B cell lymphoma protein-2 (c-Bcl2) and contributes to chronic infection and disease (15, 56, 65, 75). While v-cyclin and v-Bcl2 have clear roles in γHV68 pathogenesis, both viral genes are dispensable for virus replication (7, 15, 69) yet are required for in vivo persistence in immune-deficient mice (15).

Autophagy is a tightly coordinated self-digestion pathway required for survival during cellular and organismal stress. While autophagy is a normal steady-state cellular process (74), this physiologic pathway has been implicated in either the pathogenesis of or the response to a broad spectrum of diseases, including cancer and infection (33). In the setting of chronic hypoxia, autophagy allows sustained viability of cardiomyocytes and is implicated in the reversal and recovery of arrested cell function following reperfusion (45, 80, 81). Autophagic cells can recover from stress, provided the source of stress is abrogated early enough (6). Furthermore, tumor cells can employ this pathway in recovery from and survival of the metabolic stress associated with unrestricted growth (20, 21, 33). Autophagy also promotes resistance to anoikis, or detachment-induced apoptosis, an attribute conducive to metastasis in tumor cells (37). With respect to infection, many intracellular pathogens have evolved to either evade or exploit the autophagic machinery to their benefit.

In the study described in this report, we investigated the role of autophagy in EC infection and determined that autophagy is critical in the unique survival of persistently infected ECs. In addition to v-cyclin, we identified v-Bcl2 to be a critical viral factor in the survival of persistently infected ECs. We demonstrated that the altered phenotype of surviving, persistently infected ECs was reversible upon disruption of viral late gene synthesis. These findings suggest manipulation of autophagy as a viral strategy for promoting viral persistence in a cell type-specific manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cell culture.

The endothelial cell line MB114 (50) was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 U/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate (complete DMEM). Where indicated, medium was supplemented with 100 mM trehalose (Sigma Chemical, Saint Louis, MO) to induce autophagy, for a minimum of 48 h. 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) is a drug which inhibits the formation of autophagosomes at concentrations of 1 to 10 mM (59). To pharmacologically inhibit autophagy in infected endothelial cells, cells were cultured in 10 mM 3-MA for the first 48 h of infection.

γHV68 WUMS (ATCC VR-1465) and all recombinant viruses were grown and titers were determined as previously described (72). MB114 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 PFU per cell and cultured as previously described (63). Briefly, nonadherent cells collected at the indicated times postinfection were centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in complete RPMI. Where indicated, morphology of infected and nonadherent cells was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis of forward and side scatter properties as done previously (63). In certain experiments, cells were treated with 200 μg/ml phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) in complete RPMI beginning at 3 or 4 days postinfection, to block viral DNA replication. Effective block of viral replication was confirmed by plaque assay titers. Titers were reduced 97.5% after 48 h and 99.4% after 6 days compared to those for untreated cells.

Generation of stable EC lines.

The following retroviral vectors for stable gene expression were used: pBABE–tandem fluorescence-tagged LC3 (tfLC3), pBABE-tfLC3G120A, FUGW–v-cyclin, and MiT-M11. pBABE-tfLC3 and pBABE-tfLC3G120A were kind gifts from Jayanta Debnath (University of California, San Francisco, CA) (5). MiT (47) and MiT-M11 were kind gifts from Phillipa Marrack (National Jewish Health, Denver, CO). Lentiviral vector FUGW (containing the ubiquitin-C promoter) and packaging plasmids were kindly provided by Carlos Lois (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) (39). Briefly, the 293T producer cell line was cotransfected with retroviral plasmid and helper plasmid in a 4:1 ratio by calcium phosphate precipitation (23). Supernatants were collected at 48 h posttransfection, Polybrene was added to a final concentration of 8 μg/ml, and the mixture was immediately added to MB114 cells. MB114 cells were selected by the following methods: with 2.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) for pBABE transductions, by flow cytometric sorting of green fluorescence protein (GFP)-positive (GFP+) cells for FUGW transductions, or by separation following anti-Thy1.1–phycoerythrin (PE) [CD90.1, clone OX-7, mouse IgG1(κ); BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA] staining on anti-PE MultiSort beads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA) for MiT transductions.

Virus titer from supernatant.

To measure cell-free virus titer from infected cultures, supernatants were collected at the indicated times during culture and analyzed by plaque assay. Samples were thawed and plated onto NIH 3T12 cells in 12-well plates in triplicate. Infection was performed at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were overlaid with a 1:1 mix of DMEM and carboxymethyl cellulose plus amphotericin B (Fungizone; final concentration, 250 ng/ml). Plates were incubated for 7 days at 37°C. On day 7, carboxymethyl cellulose was removed and plates were stained with 0.35% methylene blue in 70% methanol and rotated for 15 to 20 min, before they were rinsed with water and counted on a light box. All titers were determined in parallel with a laboratory standard of wild-type (wt) γHV68 at a predetermined titer.

RNA interference.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes against ATG7 or ATG12 (14) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA). For siRNA transfection, cells were seeded at 8 × 104 cells per well in 12-well dishes, transfected with four siRNA duplexes against ATG7 and four siRNA duplexes against ATG12 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to a final concentration of 120 nM per duplex, and incubated for 48 h. Cells were split 1:3 into six-well dishes for infection experiments.

Anoikis assays.

Tissue culture plates were coated with 12 mg/ml poly-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA; Sigma Chemical, Saint Louis, MO) in 95% ethanol and incubated at 37°C for at least 3 days until dry. Cells were plated on poly-HEMA-coated plates or upright flasks at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml, and trypan blue exclusion counts were performed 12 and 36 h after the cells were plated. Metabolism was measured by a colorimetric method based on conversion of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Millipore, Billerica, MA) to a formazan product. Briefly, 100 μl of medium containing 2 × 104 cells was placed into each well of a 96-well plate in triplicate, and 10 μl of MTT reagent was added to all wells to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Cells were incubated with the MTT reagent for 4 h at 37°C. The reactions were terminated with 100 μl/well of color development solution, and absorbances were read at 570 nm.

Western analysis.

Cells were collected and boiled in Laemmli buffer for 10 min. Total protein concentration of each cell extract was determined by Lowry assay (DC protein assay kit; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Total protein extract was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were electrotransferred (ThermoFischer Scientific, Portsmouth, NH) onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked for 1 h. Western blots were incubated with the following antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3 at 1:1,500 (MBL International, Woburn, MA), mouse monoclonal anti-p62 at 1:100 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Atg7 at 1:100 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Atg12 at 1:500 (Cell Signaling), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 at 1:2,000 (Sigma Chemical), rabbit polyclonal anti-γHV68 v-cyclin at 1:2,000 (69), and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin at 1:1,000 (Sigma Chemical). Blots were washed, incubated with donkey antimouse or donkey antirabbit antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) at 1:6,000 for 1 h, and visualized using ECL Plus Western detection (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). p62 protein abundance was quantified by scanning densitometry using Kodak Molecular Imaging software (version 4.0.3) with normalization to the β-actin signal. Signals were measured as an integrated volume with correction for a defined background, and p62 signals were normalized to β-actin signals. Following normalization, p62 abundance in the various groups was expressed relative to p62 abundance under mock infection conditions.

Flow cytometry.

For viability studies, cells were washed twice in 1× annexin V binding buffer (BD Bioscience) and resuspended in either 0.5 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI), annexin V-Alexa Fluor 647 at 1:100 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), or 0.5 μg/ml PI plus 5 μl annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD Bioscience). Following 15 min incubation, cells were centrifuged (5 min, 1,000 × g), washed twice in 1× annexin V binding buffer, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Surface marker staining and forward versus side scatter analysis of morphology were carried out as previously described (63). Briefly, for surface staining, cells were washed twice and resuspended in one of the following primary antibodies: CD106-biotin [rat, IgG2a(κ), clone 429 (MVCAM.A)], CD54-FITC [Armenian hamster, IgG1(κ), clone 3E2], or Thy1.2-allophycocyanin [APC; rat, IgG2a(κ), clone 53-2.1]. Following a 45-min incubation, cells were washed, resuspended in buffer or streptavidin-APC (BD Bioscience), incubated, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

For analysis of tfLC3 localization, infected cells were collected at 24 and 72 h postinfection. Mock-infected cells and cells cultured in 100 mM trehalose were collected with 72-h-infected samples. Following collection, cells were washed twice in a solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2% fetal calf serum, and 0.1% NaN3 (herein referred to as “buffer A”), resuspended in 25 μl PBS, passed through a 35-μm-pore-size nylon mesh (BD Bioscience), slowly added to an equal volume of ultrapure electron microscopy (EM)-grade formaldehyde (final concentration, 1%; Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA), and shipped overnight, on ice, to Amnis Corporation (Seattle, WA) for collection and analysis. Cells were acquired on an ImageStream multispectral imaging flow cytometer prototype using 200-mW, 488-nm and 90-mW, 561-nm laser powers, and files were analyzed using IDEAS software. Files of 3,000 to 5,000 events were collected for each experimental sample, and single-color controls were used to create a compensation matrix that was applied to all files to correct for spectral cross talk. GFP+/mCherry-positive (mCherry+) cells were gated for spot counting. The spot count feature enumerates the number of bright GFP or mCherry puncta per cell.

GFP-LC3 localization in primary lung ECs.

Primary ECs were isolated from lungs of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice (48) using methods previously reported (42, 63). Cells were grown on glass coverslips for 24 h and infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 0.05 PFU/cell. Coverslips were washed in PBS, fixed in 2% ultrapure EM-grade formaldehyde (Polysciences Inc.) for 15 min, and allowed to dry completely before they were mounted on slides with Prolong gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen). Cells were imaged using an Olympus IX81 inverted motorized microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA IIER monochromatic charge-coupled-device camera (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA).

Limiting dilution PCR detection of γHV68-infected cells.

The frequency of surviving ECs containing the γHV68 genome was determined using a previously described nested PCR assay (ligation-dependent PCR) with single-copy sensitivity to detect gene 50 of γHV68 (70). Briefly, a series of six 3-fold dilutions from 300 cells/well to 1 cell/well were performed for each of the following: uninfected MB114 cells, untreated nonadherent surviving ECs at 18 days postinfection, and PAA-treated and adherent surviving ECs at 18 days postinfection. Plated cells were lysed overnight in proteinase K, followed by two rounds of nested PCR. Reactions were performed on 6 replicates per dilution per sample, and products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel and identified by ethidium bromide staining. PCR sensitivity was quantitated using 10, 1, or 0.5 copies of a gene 50-containing plasmid (pBamHI N) diluted in 104 uninfected NIH 3T12 cells. No viral gene 50 was detected in uninfected ECs or in negative-control samples, while PAA-treated and untreated cells were identically and uniformly positive for viral gene 50 at all cell dilutions (n = 2 independent experiments).

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA), using the paired Student's t test to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

EC survivors of γHV68 infection show signs of autophagy.

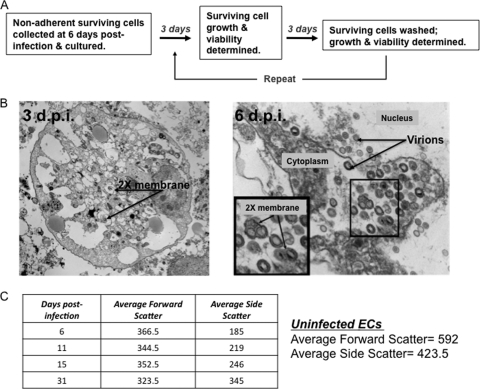

Previously, we demonstrated that a population of surviving, nonadherent ECs remains following γHV68 infection. We cultured these survivor cells and demonstrated that they have an altered phenotype, proliferate in culture, and continue to produce new infectious virions (63) (Fig. 1A). Autophagy is a cellular prosurvival pathway that is activated in response to stress. It involves sequestration of cytoplasmic components in double-membrane vesicles that are subsequently degraded upon fusion with lysosomal compartments. In the setting of prolonged autophagy, cells characteristically show increased granularity, corresponding to increased autophagosome formation, and decreased size, corresponding to the catabolic nature of this process. Transmission electron micrographs of the surviving ECs at 3 and 6 days postinfection revealed the presence of double-membrane structures suggestive of autophagosomes (Fig. 1B). Previously, we demonstrated, by flow cytometric analysis of forward and side scatter properties, that surviving ECs have a more uniform morphology than uninfected ECs (63). Over later time points postinfection, we observed that the cells became increasingly small, vesiculated, and phase dark over time. Quantitative flow cytometric analysis further revealed that, over time, the surviving ECs show decreased forward scatter, corresponding to decreased cell size, and increased side scatter, corresponding to an increase in internal granularity (Fig. 1C). These observations led us to investigate autophagy as a candidate cellular pathway in EC survival of γHV68 infection.

Fig. 1.

Morphological analysis of persistent γHV68-infected ECs. Previously, we showed that a population of surviving, nonadherent ECs remains following γHV68 infection and that these survivor cells have an altered phenotype. (A) Schematic representation of EC infection and analysis. Surviving nonadherent cells were cultured and analyzed for virus production, cell growth, and viability as previously described (63). (B) Transmission electron micrographs of surviving, nonadherent ECs at 3 (left panel) and 6 (right panel) days postinfection (d.p.i.). As previously reported, MB114 cells were pelleted and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution, and samples were processed and imaged by Gary Mierau, Children's Hospital Department of Pathology/Laboratory Services, Aurora, CO. Sections, approximately 80 nm in thickness, were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate prior to examination at 60 kV with an EM-10 transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Images revealed virus particles throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm, as well as double-membrane structures suggestive of autophagosomes (arrows). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of surviving, nonadherent EC morphology. Nonadherent MB114 cells were collected at 6 days postinfection and cultured, and their forward and side scatter values were determined by flow cytometry at the indicated times postinfection. Standard beads were run as controls for each experiment.

Pharmacologic manipulation of autophagy alters EC survival of γHV68 infection.

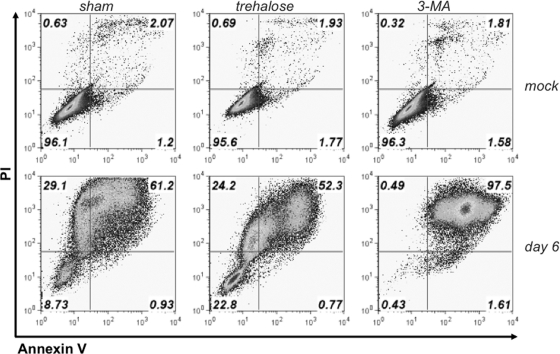

Autophagy can be induced and blocked by trehalose and 3-MA, respectively (57, 59). To determine whether cellular autophagy could influence the survival of ECs to productive infection, we treated ECs with 100 mM trehalose or with 10 mM 3-MA in the presence or absence of infection prior to analysis of cell viability at 6 days postinfection (Fig. 2). We demonstrated that untreated ECs were fully viable regardless of autophagy modulation (Fig. 2, upper panels); however, upon virus infection (Fig. 2, lower panels), trehalose treatment dramatically increased the percentage of viable (PI- and annexin V-negative) cells, while 3-MA treatment dramatically increased the apoptotic (PI- and annexin V-positive) cells. These data suggest that EC survival of productive viral infection is highly sensitive to manipulation of autophagy and that increased autophagy correlates with increased survival.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacologic manipulation of autophagy affects endothelial cell survival of γHV68 infection. Mock-infected cells (upper panels) and nonadherent, surviving MB114 endothelial cells (lower panels) at 6 days postinfection. One hour after infection, cell monolayers were rinsed with PBS and replenished with medium alone (sham treatment), 100 mM trehalose, or 10 mM 3-MA. Following a 48-h incubation, all conditions were replenished with medium alone. Nonadherent cells were collected at 6 days postinfection and stained with annexin V and PI, and viability was determined by flow cytometry. Gates were set on unstained cells.

Specific viral oncogenes are required for optimal EC survival of γHV68 infection.

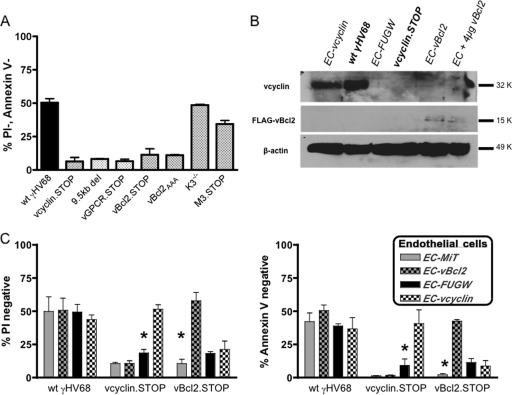

We demonstrated that viral DNA replication and/or late gene synthesis is required for the unique ability of ECs to survive γHV68 infection (63). Further, we showed, at several times postinfection, that v-cyclin promotes optimal survival but was dispensable for virus replication (63) in ECs. Though we initially identified the v-cyclin to be required for optimal EC survival, it was very likely that additional viral genes facilitate persistent EC infection. To determine whether the v-cyclin was uniquely able to promote EC survival following γHV68 infection, we tested additional candidate genes for their contribution to EC survival: M11, M3, mK3, M1, M2, v-GPCR, and the viral polymerase III transcripts. Importantly, these viral genes have previously been identified as being dispensable for lytic replication in vitro (3, 4, 7, 66, 71). The viability of ECs (MB114 cells) infected with wt γHV68 or gene-specific mutant viruses was examined at 6 days postinfection by staining with annexin V and PI (Fig. 3A). ECs infected with wt virus were 50.43% (±2.98%, standard error of the mean [SEM]) viable (annexin V negative, PI negative). As expected, ECs infected with a v-cyclin mutant γHV68 (v-cyclin.STOP) had significantly fewer viable cells (6.34% ± 3.03% [SEM]). The viability of ECs infected with viruses mutant in either M3 (M3.STOP) or mK3 (K3−T−) did not differ significantly from that of wt infected cells (34.4% ± 2.63% [SEM] and 48.63% ± 0.64% [SEM], respectively). Interestingly, four additional viral mutants were defective in supporting EC survival during persistent infection. These included a mutant virus containing a large deletion in the left end of the genome that is deficient in M1, M2, and the viral polymerase III transcripts (4, 8), a mutant virus deficient in the v-GPCR transcript (51), and two different v-Bcl2 mutant viruses (v-Bcl2.STOP and v-Bcl2AAA) with significantly fewer viable cells (11.47% ± 4.48% [SEM] and 11.03% ± 0.62% [SEM], respectively). Thus, our viability screen identified several additional candidate genes that play a part in EC survival and persistence during γHV68 infection. As was true for the v-cyclin, we and others have previously demonstrated that v-Bcl2 plays a role in persistent infection in vivo (15). Furthermore, v-cyclin and v-Bcl2 are both viral oncogenes with the capacity to regulate the related processes of cell cycle and cell survival.

Fig. 3.

Optimal EC survival of γHV68 infection requires v-cyclin and v-Bcl2. (A) Viability of MB114 cells at 6 days postinfection. MB114 cells were collected at 6 days postinfection with the indicated γHV68 mutant (MOI = 5), stained with annexin V and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of annexin V-negative (Annexin−), PI-negative (PI−), viable cells were determined relative to unstained cells (n = 3 per virus). (B) Thirty micrograms of lysate from ECs transduced with either FUGW- v-cyclin (EC-vcyclin), FUGW (EC-FUGW), or MiT–v-Bcl2 (EC-vBcl2) was loaded and membranes were probed with anti-v-cyclin, anti-FLAG, and anti-β-actin antibodies. ECs at 36 h postinfection with either wild-type γHV68 (wtγHV68) or v-cyclin mutant virus (vcyclin.STOP) were included as positive and negative controls for v-cyclin expression, respectively. ECs transfected with 4 μg of MiT–v-Bcl2 plasmid (EC + 4 μg vBcl2) were included as a positive control for FLAG–v-Bcl2 expression. K, molecular weight (in thousands). (C) Viability of MB114 cells stably expressing v-cyclin (EC-vcyclin) or v-Bcl2 (EC-vBcl2). MB114 cells transduced with either MiT, MiT–v-Bcl2, FUGW, or FUGW–v-cyclin were collected at 6 days postinfection with the γHV68 mutant indicated on the x axis (MOI = 5), stained with either PI or annexin V, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of PI-negative (left panel) and annexin V-negative (right panel) viable cells relative to unstained cells were determined. Significant differences were observed in percent PI negative and annexin V negative between EC–v-cyclin and EC-FUGW following infection with v-cyclin-deficient virus (P = 0.0013 and P = 0.0498, left and right panels [asterisks], respectively). Percentages of PI-negative and annexin V-negative cells were significantly different between EC-MiT and EC–v-Bcl2 following infection with v-Bcl2-deficient virus (P = 0.0027 and P < 0.0001, left and right panels [asterisks], respectively) (n = 3).

To further test the requirement for these two viral genes in infected EC survival, we created ECs that stably expressed either v-cyclin (EC–v-cyclin) or v-Bcl2 (EC–v-Bcl2) (Fig. 3B) to determine whether these viral oncogenes can be provided in trans. The vector control EC-MiT- and EC-FUGW-transduced cells, as well as the EC–v-Bcl2- and EC–v-cyclin-transduced cells, displayed wild-type EC characteristics during normal culture and were indistinguishable from one another, with the exception of a mild growth advantage of the EC–v-cyclin cells (see Fig. 7B). These stably transduced cell lines, as well as vector control cell lines, were then infected with either wt, v-cyclin.STOP, or v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68, and the viability of cells was determined at 6 days postinfection. Consistent with our previous viability analysis (63), control vector-transduced cells, EC-MiT and EC-FUGW, demonstrated more reduced viability in v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection than in wt γHV68 infection. However, EC–v-cyclin cells stably expressing the v-cyclin had restored viability upon infection with v-cyclin.STOP γHV68. Compared to EC-FUGW cells, there were significantly greater percentages of EC–v-cyclin cells that were PI negative (P = 0.0013) and annexin V negative (P = 0.0498) following v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection. As demonstrated in our viability screen, ECs infected with v-Bcl2.STOP virus had reduced viability relative to those infected with wt virus, and viability was specifically restored in EC–v-Bcl2 cells. Compared to EC-MiT cells, there were significantly greater percentages of EC–v-Bcl2 cells that were PI negative (P = 0.0027) and annexin V negative (P < 0.0001) following v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68 infection. Upon infection with either viral mutant, v-cyclin.STOP or v-Bcl2.STOP, control vector-transduced cells (EC-MiT and EC-FUGW) had viability defects comparable to those of unmanipulated ECs. Notably, stable expression of the v-Bcl2 did not improve viability upon infection with v-cyclin.STOP γHV68, nor did stable expression of the v-cyclin improve viability upon infection with v-Bcl2.STOP virus. Taken together, these findings indicate that v-cyclin and v-Bcl2 can each function in trans to facilitate EC survival after infection with corresponding mutant viruses and do not require genome-specific regulation of expression. However, neither viral gene was sufficient to bypass the defect of a virus lacking the other effector, suggesting that v-Bcl2 and v-cyclin play distinct and independent roles in the optimal survival of infected ECs.

Fig. 7.

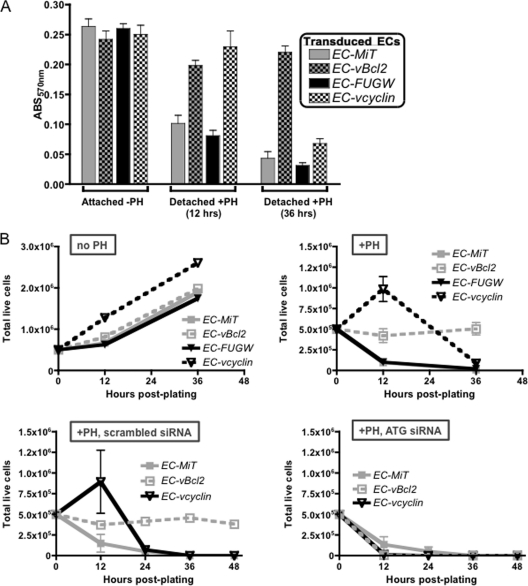

γHV68 v-Bcl2 conveys autophagy-dependent protection to ECs from anoikis in the absence of infection. Anoikis of ECs stably expressing v-cyclin (EC-vcyclin) or v-Bcl2 (EC-vBcl2). ECs transduced with either MiT, MiT–v-Bcl2, FUGW, or FUGW–v-cyclin were cultured on regular or poly-HEMA (PH)-coated flasks. Where indicated, transduced ECs were transfected with either a scrambled siRNA or Atg7 and Atg12 siRNAs 48 h before they were plated. (A) MTT assay of EC viability at the indicated times postplating. ABS, absorbance. (B) Trypan blue exclusion counts of live cells were performed at the indicated times postplating. Results are from three independent experiments.

EC survivors of γHV68 infection demonstrate activation of the prosurvival autophagy pathway.

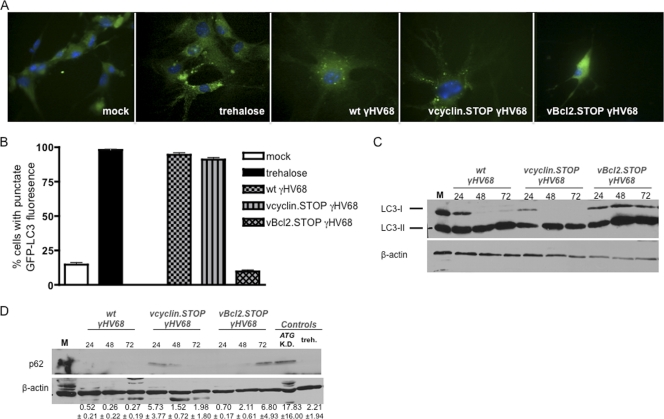

Autophagy is characterized by autophagosome formation and by multiple subcellular and biochemical alterations (74). Specifically, the cytoplasmic protein LC3-I is lipidated upon induction of autophagy to associate with the autophagosome as LC3-II. Therefore, conversion of cytoplasmic LC3-I to punctate, autophagosome-associated LC3-II is a widely used indicator of autophagy (28). Previously, we reported that the ability to survive γHV68 infection was relevant not only to EC lines from various anatomic locations but also to primary lung ECs (63). Therefore, we first sought to test the status of autophagy in ECs during γHV68 infection of primary ECs purified from GFP-LC3 transgenic mouse lungs. These mice express a GFP-LC3 fusion protein which serves to fluorescently mark autophagosomes (48). ECs showing ≥10 GFP-LC3 puncta per cell were scored as autophagic. As a positive control, we analyzed the consequence of trehalose treatment in primary GFP-LC3 ECs. In primary GFP-LC3 ECs, the number of autophagic ECs increased over the number of mock-treated ECs following trehalose treatment (Fig. 4A and B). At 48 h, both v-cyclin.STOP- and v-Bcl2.STOP-infected ECs showed decreased viability relative to ECs infected with wt γHV68. These results were consistent with our data establishing v-Bcl2 and v-cyclin in optimal EC survival of γHV68 infection. However, the number of autophagic ECs increased dramatically over the number of mock-treated cells following both wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection, whereas very few autophagic GFP-LC3 puncta were enumerated at 48 h postinfection with v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68. Taken together, these data demonstrate the induction of autophagy during γHV68 infection of ECs.

Fig. 4.

Biochemical markers of increased autophagic flux differed in endothelial cells infected with v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68 and cells infected with wild-type and v-cyclin.STOP viruses. Primary GFP-LC3 lung ECs were treated with 100 mM trehalose, infected with 0.05 PFU/cell of the indicated virus, or mock treated. At 48 h, fluorescent images were captured (A) and the percentages of autophagic cells under each experimental condition were quantified (B). (A) Images captured using a ×40 oil immersion objective. (B) Percentage of autophagic cells determined as the percentage of cells with ≥10 puncta of GFP per cell. Six random fields of 100 cells were quantified per condition, and images are representative from two independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot of LC3 from infected MB114 cells. Thirty micrograms of total protein was loaded per lane from MB114 cells 72 h after mock infection (lane M) and MB114 cells at the indicated times (in hours, indicated above each lane) postinfection with either wild-type, v-cyclin.STOP, or v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68. Blots were probed with anti-LC3 antibody and anti-β-actin antibody. Positions of LC3-I and LC3-II are indicated. (D) p62 abundance during γHV68 infection. Thirty micrograms of total protein was loaded per lane from mock-infected (lane M), Atg7 and Atg12 siRNA-treated (lane ATG K.D. [knockdown]), or trehalose-treated (treh.) MB114 cells or MB114 cells infected for the indicated times with either wild type, v-cyclin.STOP, or v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68. K.D., blots were probed with anti-p62 antibody and anti-β-actin. Levels of p62 protein relative to that in mock-infected cells were determined by densitometry, with values normalized to those for β-actin. Values listed are the averages from three independent experiments, with SEMs indicated.

Because our analysis of GFP-LC3 localization in primary ECs was consistent with the induction of autophagy in γHV68-infected ECs, we then analyzed infected MB114 ECs for expression of protein markers of autophagy. Cytoplasmic LC3-I and lipidated LC3-II forms can be distinguished by immunoblot analysis (49). LC3-I and LC3-II were detected comparably in ECs at 72 h following mock infection, suggesting basal autophagy in ECs (Fig. 4C). From 24 to 72 h following wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection, unmodified LC3-I levels were reduced or undetectable, whereas LC3-II levels were constant. In contrast, from 24 to 72 h following v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68 infection, no changes in LC3-I were observed. These observations are consistent with increased conversion of cytoplasmic LC3-I to autophagosome-associated LC3-II in the wt- and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68-infected ECs but not in the v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68-infected cells.

p62 also serves as a protein marker of autophagy because it is incorporated into the completed autophagosome and degraded in autolysosomes. Thus, steady-state p62 levels are a reflection of autophagic status, and p62 accumulation indicates inhibition or blockade of autophagy (28, 53, 76). p62 was not detectable in EC controls following autophagy induction by trehalose, and control cells transfected with siRNAs targeting the critical autophagy genes ATG7 and ATG12 demonstrated an accumulation of p62. p62 was readily detectable in ECs at 72 h following mock infection (Fig. 4D). During infection with wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68, p62 was difficult to detect and detectable p62 decreased over time. In contrast, p62 levels increased from 24 to 72 h postinfection with v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68.

Taken together, these data provided additional evidence for the induction of autophagy and autophagic maturation during γHV68 infection of ECs. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that v-cyclin and v-Bcl2 influence EC survival of persistent infection in distinct ways, such that the absence of v-Bcl2 uniquely results in altered autophagy or survival of autophagic cells.

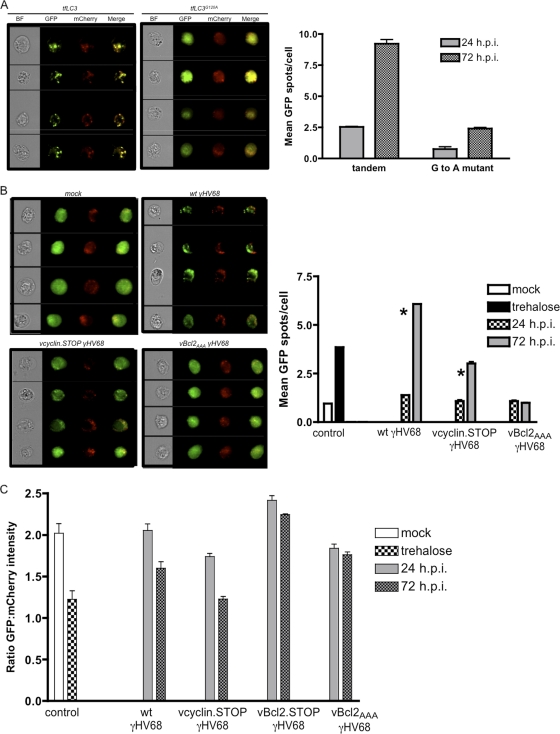

Quantitative analysis of LC3 localization in surviving infected ECs.

Quantification of autophagosome-associated LC3 by fluorescent microscopy is commonly used to measure the induction of autophagy. We demonstrated induction of autophagy by quantification of autophagosome-associated LC3 by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 4A and B). However, this approach relies on an observer's quantitation of puncta per cell from cells fixed onto slides, making it arduous to realistically analyze a large number of cells. To more quantitatively and objectively test the status of autophagy during γHV68 infection of ECs, we also generated ECs that stably expressed a tfLC3: mCherry-GFP-LC3 (27, 53). With this tandem fluorescently tagged LC3 protein, it is possible to obtain two levels of information about LC3 localization and autophagosome formation. First, LC3 relocalization to autophagosomes can be visualized and quantified as fluorescent puncta within the cell. Second, this tandem fluorophore is capable of identifying autophagosomes which have fused to lysosomes, a hallmark of autophagic maturation. Because GFP, but not mCherry, fluorescence intensity is sensitive to acidic lysosomal hydrolases, GFP emission is attenuated after lysosome fusion, while mCherry signals remain bright. Thus, the GFP/mCherry ratio over time indicates progression through the autophagosome to autophagolysosomal pathway. The C-terminal glycine (Gly120) of LC3 is modified to allow binding of the protein to the autophagosome surface. Corresponding control ECs were generated in which an alanine substitution for this glycine (tfLC3G120A) prevents association of the reporter protein with the autophagosome and thus serves as a control for nonspecific aggregation of fluorescent proteins (27, 53).

To quantify tfLC3 localization in infected ECs, we used multispectral imaging flow cytometry to analyze tfLC3 localization in a large number of ECs under various experimental conditions. This approach was previously employed to detect and quantify autophagosome-associated GFP-LC3 puncta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (35). We measured LC3 fluorescence after γHV68 infection of either EC-tfLC3 or EC-tfLC3G120A. This analysis revealed that wt γHV68 infection resulted in a significant increase in the number of autophagic LC3 puncta, or GFP spots, per cell after 72 h of wt γHV68 infection (Fig. 5A). This increase was not observed in EC-tfLC3G120A, demonstrating that LC3 puncta were not due to nonspecific aggregation (Fig. 5A) related to virus infection.

Fig. 5.

Image-based flow cytometric analysis of autophagy in infected ECs. ECs transduced with tfLC3 were collected at 24 and 72 h postinfection and analyzed using Amnis ImageStream multispectral flow cytometry. ECs transduced with tfLC3G120A were included as a control for nonspecific aggregation of fluorescent molecules with infection. GFP-positive and mCherry-positive cells were gated for spot counting. The spot count feature determined the number of bright LC3-GFP puncta per cell, which are also mCherry positive. (A) Representative EC images at 72 h postinfection (BF = bright field) and bar graph of LC3-GFP spot mean in ECs at 24 or 72 h postinfection (h.p.i.) with wt γHV68. (B) LC3 localization in infected ECs. Representative EC images at 72 h postinfection. ECs transduced with tfLC3 were collected at 24 and 72 h postinfection with the indicated virus and analyzed using Amnis ImageStream multispectral flow cytometry. Cells positive for GFP and mCherry were gated for GFP spot counting. Two thousand to 5,000 cells were collected per condition, and results are the averages of three independent experiments. (Graph) LC3-GFP spot mean in ECs at 24 or 72 h postinfection with the indicated virus. The spot count feature determined the number of bright LC3-GFP puncta per cell. Significant differences in mean LC3-GFP puncta per cell (B) were observed between 24 and 72 h postinfection with wt and v-cyclin-deficient viruses (*, P < 0.0005 and P < 0.0001, respectively). (C) Ratio of GFP to mCherry intensity in ECs at 24 or 72 h postinfection with the indicated virus. Mock-infected and trehalose-treated ECs were included as controls. Two thousand to 5,000 cells were collected per condition.

Because we did not detect increased GFP-LC3 puncta in primary ECs infected with v-Bcl2.STOP γHV68 (Fig. 4A and B) but did following infection with both wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68, we analyzed tfLC3 localization following infection with these viral mutants, as well as infection with an independent v-Bcl2 mutant virus, v-Bcl2AAA. This v-Bcl2AAA virus bears a point mutation in the SGR amino acids of the BH1 domain of v-Bcl2, rendering it defective in vivo for both efficient reactivation from latency and efficient persistent γHV68 replication (38).

While basal autophagy, as indicated by tfLC3 puncta (indicated by the mean spot count) at 72 h postplating of mock-infected ECs, varied between experiments, a significant increase in autophagic LC3 puncta per cell was observed following infection with either wt γHV68 or v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 at between 24 and 72 h postinfection, yet no change was observed from 24 to 72 h following infection with the v-Bcl2AAA mutant virus (Fig. 5B).

To further validate this analytical method for the tandem tag in our system, we analyzed the consequence of treatment with trehalose, a known inducer of autophagy (57), in tfLC3-expressing ECs. Compared to mock-infected cells, trehalose treated EC-tfLC3 showed an increase in the mean number of GFP spots per cell (Fig. 5B) and a decrease in GFP fluorescence relative to mCherry fluorescence (Fig. 5C), consistent with the formation and subsequent fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes.

ImageStream-acquired fluorescent micrographs of tfLC3 ECs at 72 h postinfection demonstrated many fluorescent GFP spots per cell following wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection, and merge analysis revealed puncta with decreased GFP intensity relative to mCherry intensity (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrated that autophagy was induced during wt and v-cyclin.STOP γHV68 infection of ECs and were consistent with efficient autophagosome-to-lysosome fusion. In contrast, no appreciable increase in fluorescent puncta was observed following v-Bcl2AAA mutant virus infection (Fig. 5B), with merge analysis revealing little to no decrease in the GFP-to-mCherry ratio following infection with either the v-Bcl2.STOP virus or the v-Bcl2AAA mutant virus (Fig. 5C). This concordance between the mean GFP spot number and relative GFP and mCherry intensity in cells infected with two independent v-Bcl2 mutant viruses suggests that induction of autophagy is not as appreciable in surviving ECs in the absence of v-Bcl2 as in surviving ECs with wild-type and v-cyclin mutant virus infection.

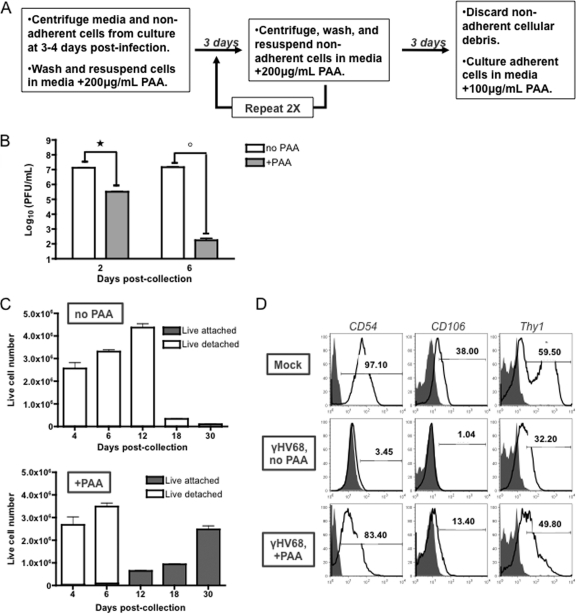

Reversion of infected EC phenotype by disruption of productive γHV68 infection.

Autophagy sustains cell survival during stress through catabolism. Importantly, if relieved of such stress (i.e., starvation, ischemia), autophagic cells are capable of recovery. However, when carried out to completion, autophagy leads to cell death. Previously, we determined that, unlike uninfected ECs, surviving cells grow nonadherently, are very uniform in size and internal granularity, and are altered in surface protein expression (63). Because this outcome depends on productive viral infection and requires intact autophagic machinery, we tested whether disruption of viral gene expression equated to relieving stress in the phenotype of surviving, infected ECs. PAA is an inhibitor of viral DNA polymerase and late gene synthesis (18). At 3 to 4 days postinfection (after the viral induction of autophagy demonstrated in Fig. 4 and 5), surviving nonadherent ECs were collected and cultured as previously described (63) or were cultured with the addition of PAA (Fig. 6A). Supernatant titers were dramatically lower in surviving ECs cultured in PAA than in those cultured in the absence of PAA, indicating effective block of virus replication (Fig. 6B). As previously observed, all surviving ECs were productively infected and grew only in suspension, and no viable cells were detected on culture flask bottoms (Fig. 6C, top panel, no PAA). However, as early as 3 days after culture in PAA, a few surviving ECs per field again attached to the culture flasks, and after 9 days in PAA, these cells put out fibroblast-like processes characteristic of subconfluent ECs (data not shown). After 12 days in PAA, the number of adherent cells began to increase (Fig. 6C, bottom panel), at which time nonadherent cellular debris was removed and the adherent cells were grown to confluence. These findings indicate that surviving ECs can recover the adherent growth that is typical of ECs following disruption of viral late gene synthesis.

Fig. 6.

Surviving ECs recover EC phenotype when viral DNA replication is disrupted. (A) EC survivor culture conditions for PAA treatment. Nonadherent cells were collected at 3 to 4 days postinfection and cultured in medium with or without 200 μg/ml PAA. Cells were resuspended in fresh medium plus 200 μg/ml PAA every 3 days. On the 9th day of culture in PAA, nonadherent cells were discarded and adherent cells were cultured to confluence in medium plus 100 μg/ml PAA. (B) Nonadherent ECs were collected at 3 to 4 days postinfection and cultured in medium plus 200 μg/ml PAA or in medium alone. At the indicated times postcollection, cell-free supernatants were collected and titers were determined by plaque assay. Significant titer differences were observed between PAA and medium-alone culture conditions (*, P = 0.0002; °, P = 0.0006). (C) Trypan blue counts of total live nonadherent (white) and live adherent (gray) cells. Surviving ECs were cultured in the absence (top panel) or presence (bottom panel) of PAA, and the numbers of live adherent and nonadherent cells were enumerated at the indicated times postcollection. (D) EC survivor cell surface protein expression. Uninfected cells (top row) and infected survivor cells cultured for 30 days in medium alone (middle row) or medium plus PAA (bottom row) were analyzed for cell surface expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and Thy1 by flow cytometry. Fluorescence was determined relative to that of unstained cells (gray). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

To further test the effect of blocking viral gene synthesis on the infected EC survivor phenotype, we compared the expression of cell surface proteins on surviving ECs cultured in the presence and absence of PAA. Previously, we reported that, unlike uninfected ECs (Fig. 6D, top row), surviving cells do not express intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) or vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; CD106) on their surface (Fig. 6D, middle row). Thy1 expression, however, is maintained on the surface of infected EC survivors. Interestingly, like uninfected ECs, infected EC survivors cultured in PAA were positive for surface expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and Thy1 (Fig. 6D, bottom row). That is, following disruption of viral gene synthesis, surviving ECs recovered anchorage-dependent growth and surface expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1.

We analyzed PAA-treated and adherent cells with PAA-untreated and nonadherent cells at 18 days postinfection, a time when PAA-treated cells have substantially recovered substrate attachment and endothelial cell morphology, by sensitive limiting dilution PCR detection of viral genome. We found that while PAA treatment blocked virus replication and production and restored normal endothelial cell morphology by this time, viral genome was retained. Indeed, viral DNA was detected in all cells down to single-cell dilutions (data not shown). This efficient retention of viral DNA in PAA-treated ECs is consistent with either abortive or latent infection and demonstrates that these PAA-treated cells are not cured of infection.

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that EC survivors can recover traits of their original EC phenotype upon disruption of cellular stress (productive viral infection). This reversible path toward cell death is one characteristic of the autophagy pathway.

ECs expressing viral oncogenes are protected from detachment-induced cell death.

ECs die by a process termed anoikis when detached from the extracellular matrix (46). γHV68 infection of ECs is unusual in that infected cells detach from the extracellular matrix but remain viable and productively infected for a prolonged period of time. Autophagy can protect cells from anoikis-mediated death (14, 37). Our data indicated that autophagy induction is involved in EC survival of γHV68 infection and subsequent detachment and that survival depends on two viral oncogenes, v-cyclin and v-Bcl2.

To examine the effects of viral oncogenes on anoikis in the absence of virus infection, cell metabolism of detached or adherent transduced ECs was measured by MTT assay (Fig. 7A). Coating flasks with poly-HEMA prior to cell plating mimics detachment associated with anoikis (13). Upon detachment for 12 or 36 h, control vector-transduced ECs (EC-MiT and EC-FUGW) exhibited a drastic reduction in metabolic activity compared to attached cells. The metabolic activity of v-cyclin-expressing ECs was quite high during the first 12 h but was reduced after 36 h of detachment. However, v-Bcl2-expressing ECs exhibited high metabolic activity upon detachment at both 12 and 36 h.

To further test the effects of v-cyclin and v-Bcl2 on anoikis, trypan blue viability counts were performed on adherent and detached ECs. Under adherent culture conditions, EC–v-cyclin cells had a faster proliferation rate than EC–v-Bcl2 and control vector-transduced ECs (Fig. 7B, top left panel). Similarly, when cultured as detached cells (Fig. 7B, top right panel), EC–v-cyclin cells proliferated during the first 12 h of culture; however, after 12 h the number of live v-cyclin-expressing ECs declined. The EC–v-Bcl2 cells remained viable and constant over 36 h of detached culture. Vector control-transduced ECs did not survive culture as detached cells. ECs in tilted flasks under detached conditions behaved comparably to ECs under detached conditions in poly-HEMA (data not shown). These data revealed that v-cyclin can impart a proliferative advantage to ECs both in attached cultures and early in the context of matrix deprivation and may increase the pool of surviving cells. However, v-Bcl2 expression does protect ECs from anoikis, as v-Bcl2-expressing cells maintained live cell numbers and a fully active metabolic state. As in EC survival of γHV68 infection, the viral oncogenes play independent roles in delay or protection from substrate detachment.

Because autophagy can protect cells from anoikis-mediated cell death, we tested the requirement for autophagy in survival of anoikis by transduced ECs. To inhibit autophagy in ECs, we used siRNA oligonucleotide pools targeting murine ATG7 and ATG12 (14). Knockdown of ATG7 and ATG12 was effective and did not affect EC viability under normal, adherent culture conditions (Fig. 8A to C). However, ECs knocked down in ATG7 and ATG12 plated on poly-HEMA-coated flasks were dead by 12 h postplating, regardless of viral oncogene expression (Fig. 7B, bottom right panel). When transfected with a nonspecific siRNA, ECs cultured on poly-HEMA-coated flasks proliferated and/or survived just as in the absence of siRNA (Fig. 7B, compare bottom left panel to top right panel). These data suggest that, in the setting of matrix detachment, regardless of virus infection, EC survival requires an intact autophagic pathway.

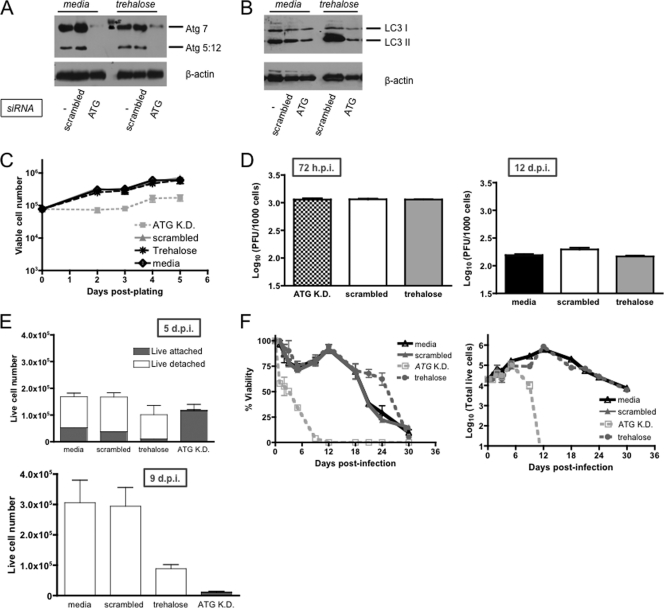

Fig. 8.

Monitoring the role of autophagy during γHV68 infection of ECs. ECs transfected with no siRNA (lanes −), scrambled siRNA, or a cocktail of siRNAs against ATG7 and ATG12 were cultured in medium for 48 h and analyzed for Atg7 and Atg12 expression to measure knockdown (A) or LC3 protein expression to measure inhibition of autophagy by Western analysis (B). The sense sequences of the individual duplexes directed against ATG7 and ATG12 are as follows: for ATG7 (GenBank accession number NM_028835), CCUCGGACCCAUGCCUCCUUUCUGGUU, CUCUUAAACCGAGGCUGUGUGGCUCUU, GCUAAAUGCCAUUUCUGGAAGUUUCAC, and CAACUGUUAUCUUUGUCCUUUGACCUU; for ATG12 (GenBank accession number NM_026217), CAGUCUUAAACUUUCAGUCUGCUUGUU, AAACACAAACCCUUCAGUAAAUUAGUU, UGGGAGAUGGGUAAGUUGGUGCUGCGU, and AACAAUAAAUUCAACAUACUUCUCCUG. In control experiments, cells were transfected with equal total amount DS Scrambled Negative (Dicer Substrate scrambled universal negative control RNA duplex; IDT). Expression of these proteins was reassessed following 48 h of trehalose treatment (4 days posttransfection). Membranes were probed with anti-β-actin antibody as a cellular loading control. (C) MB114 cells following knockdown (K.D.) of Atg7 and Atg12 or trehalose treatment. MB114 cells transfected with a scrambled siRNA or cultured alone in complete medium were included as controls. Trypan blue counts of infected MB114 cells. Results are from triplicate samples in each of two independent experiments. (D) Titers in supernatants from infected EC survivors. Nonadherent ECs were collected at the indicated times postinfection, counted, and pelleted, and titers in the supernatants were determined by plaque assay. Titers reflect the number of cell-free PFU per 1,000 cells. No significant differences in titer were observed among infected ECs treated with trehalose, knocked down for Atg7 and Atg12 proteins, or transfected with a scrambled siRNA at 72 h postinfection (h.p.i.; left panel). No significant differences in titer were observed among infected ECs transfected with a scrambled siRNA, cultured in trehalose, or cultured in medium at 12 days postinfection (d.p.i.; right panel). ECs knocked down for Atg7 and Atg12 proteins did not survive to 12 days postinfection. Data indicated the average, with SEMs shown, of three independent experiments. (E) Wild-type γHV68 infection of ECs following knockdown of ATG7 and ATG12 or trehalose treatment. ECs transfected with a scrambled siRNA or cultured in complete medium alone were included as controls. (E) Trypan blue counts of infected ECs. Live adherent (gray) and nonadherent (white) ECs at 5 and 9 days postinfection. (F) Growth and proliferation of infected ECs over 30 days postinfection. Results are from three independent experiments.

Autophagy is required for EC survival of γHV68 infection.

Our data demonstrated that autophagy is induced during γHV68 infection of ECs. We tested the requirement for autophagy in the unique ability of ECs to survive γHV68 infection and remain viable as a nonadherent cell suspension. Autophagy requires a number of highly conserved molecules called ATGs (29). ATG depletion inhibits autophagy (14). To inhibit autophagy in ECs, we used established siRNA oligonucleotide pools targeting murine ATG7 and ATG12 (14). We confirmed siRNA-mediated reduction of Atg7 and Atg12 proteins in ECs (Fig. 8A) and showed that this resulted in accumulation of p62 (Fig. 4D) and in a decrease in LC3-II during trehalose treatment (Fig. 8B). We further confirmed that ATG7 and ATG12 knockdown by siRNA resulted in a modest delay in proliferation but no changes in the viability of ECs (Fig. 8C), despite a modest delay in proliferation. Furthermore, neither siRNA-mediated reduction of Atg7 and Atg12 proteins nor trehalose treatment affected virus production in ECs (Fig. 8D). ECs cultured either in complete medium or in trehalose persisted at 5 days after γHV68 infection as a nonadherent and viable cell suspension (Fig. 8E). In contrast, most ECs with ATG7 and ATG12 knockdown were dead at 5 days postinfection, and no nonadherent, viable cells were detectable. Trypan blue exclusion counts of both adherent and nonadherent live cells revealed that ECs transfected with scrambled siRNA were viable at 5 days postinfection and that a large proportion of these viable cells was nonadherent and remained viable at 9 days postinfection (Fig. 8E). In contrast, no nonadherent surviving ECs were detected at 5 days postinfection in ATG7- and ATG12-knockdown cultures, and by 9 days postinfection only a small number of adherent viable cells remained (1 × 103 ± 5 × 103 [SEM]).

To further test the role of autophagy in the unique survival outcome of infected ECs, surviving nonadherent cells were cultured for up to 30 days and trypan blue exclusion counts were performed periodically (Fig. 8F). Consistent with our previous report of infected EC proliferation, surviving ECs transfected with no siRNA or a scrambled, nonspecific siRNA proliferated during the first 12 days of culture and remained viable for as long as 30 days postinfection. ECs cultured in trehalose also proliferated during the first 12 days of culture and remained viable for as long as 30 days postinfection. ECs knocked down in ATG7 and ATG12 did not proliferate, and all cells were dead by 12 days postinfection.

These findings indicated that the autophagy proteins Atg7 and Atg12 were required for the unique outcome of γHV68 infection in which ECs remain viable for a prolonged period of time after becoming nonadherent upon γHV68 infection.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to latent infection, in which no viral DNA amplification or production of viral progeny occurs, productive γHV infection is characterized by abundant viral gene synthesis and viral DNA amplification and culminates in the generation of viral progeny. Fibroblasts and most cell types are quickly lysed by active infection and limit virus replication to an acute infection time frame. ECs are unique in that they are productively infected yet remain viable and allow abundant and prolonged virus production (63). While γHV68 infection of ECs results in a population of viable infected cells, these surviving cells are altered in morphology and achieve anchorage-independent survival, but their proliferation is reduced and viability is not indefinite (63).

Here we demonstrate that this unique cell type-specific outcome employs the cellular autophagic machinery. With time postinfection, EC survivors became smaller and increasingly more granular and contained double-membrane structures characteristic of autophagosomes. LC3 localization and modification demonstrated increased autophagosome formation with infection in both primary and transduced cells, and tandem LC3 fluorescence ratios with p62 degradation suggested autophagosome maturation. Pharmacologic manipulation of autophagy influenced the survival of infected ECs, such that an autophagy inducer resulted in increased survival and an autophagy inhibitor resulted in decreased survival, and EC survival required the autophagy proteins, Atg7 and Atg12.

Furthermore, we identified that the v-cyclin and the v-Bcl2 genes are required for survival and persistent infection of EC yet play independent roles in this process. Both of these viral oncogenes are not required for viral replication in vitro or in healthy mice but have been found to promote the severity of γHV68-associated lymphoproliferative disease, arteritis, and acute pneumonia in immunodeficient mice (15, 36, 65, 71). Significant to this study and the persistent infection of ECs, both of these viral oncogenes are required for efficient viral persistence in vivo (15). Here, we reported that these genes are capable of transcomplementation in EC persistence but were not capable of cross-complementation. These viral oncoproteins played nonoverlapping roles in EC survival of infection; that is, v-cyclin provides a transient increase in the number of infected ECs, whereas v-Bcl2 increases the number of autophagic cells. These activities are consistent with their previously described functions in cell cycle regulation and in apoptosis and/or autophagy, respectively. Finally, it is important to note that transduction of ECs demonstrated that neither of these viral oncogenes independently induces autophagy; instead, they fulfill distinct functions during productive infection and autophagy to promote survival of infected ECs.

Antiapoptotic cellular Bcl2, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) Bcl2, and γHV68 v-Bcl2 each interact with the autophagy effector Beclin-1, and these interactions with Beclin-1 have been demonstrated to inhibit autophagy (31, 32, 41, 54) following starvation and rapamycin treatment. Thus, our results are surprising in that we consistently detected fewer autophagic, infected cells in the absence of the v-Bcl2. This apparent discrepancy may be due to several factors. First, we examined the role of v-Bcl2 during EC survival in the context of full viral infection, whereas most studies demonstrated inhibition of autophagy by v-Bcl2 expressed in isolation. There are likely viral cofactors that influence autophagic cues and components, as is consistent with our initial viability screen implicating additional viral genes. Second, the antiapoptotic function of v-Bcl2 is well established (15, 56, 65, 75), and autophagic vacuoles are detectable preceding apoptotic cell death (16). Cross talk between autophagy and apoptosis is complicated, cell type specific, and critical in the outcome of cell death (2, 12, 67). Therefore, it is possible that v-Bcl2-mediated inhibition of apoptosis allows autophagy to ensue by promoting prolonged cell survival and facilitating detection of autophagic cells. Third, this is the first report of γHV68 infection and autophagy in ECs. Basal levels of autophagy occur under normal growth conditions, and the extent of such physiologic autophagy is cell type dependent (48). Because basal autophagy is cell type specific, it is possible that cellular factors present in ECs facilitate induction of autophagy and modulate the effect of the v-Bcl2 in the context of infection. Likewise, it is possible that v-Bcl2 effects on autophagy have evolved for cell type-specific outcomes. Finally, there are stimulus-dependent differences in the effect of Bcl2 members on autophagy. Starvation and rapamycin-induced autophagy are inhibited by Bcl2 members, whereas Bcl-xL and Bcl2 overexpression increased autophagy in etoposide-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (31, 54, 60, 77), and Bcl2 overexpression does not inhibit detachment-induced autophagy in mammary epithelial cells (14). Thus, in the setting of virus-associated matrix detachment, the interaction of v-Bcl2 with the autophagic and apoptotic machinery may be complex and may differ from starvation or rapamycin stimuli.

Induction of autophagy following infection with human herpesviruses has also been shown. Infection of B cells with the human γHV Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) leads to proliferation, an outcome that requires the oncogene latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) (9, 25, 26). LMP1 can induce autophagy in a dose-dependent manner and thus modify host cell physiology (34). KSHV lytic reactivation and the viral lytic replication inducer RTA were recently demonstrated to induce autophagic activation (78). While the primary function of RTA appears to be in transcriptional transactivation, it has also been demonstrated to be capable of E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (17, 82). The former suggests that it could act indirectly during infection by transactivating other viral genes, while the latter could play a more direct role in autophagy. Finally, varicella-zoster virus induces autophagy during primary infection in vitro and in vivo (64). These examples of induction of the host autophagic machinery during herpesvirus infection lend support to the idea that viral manipulation of autophagy can be highly context dependent. Given these context-dependent examples of autophagy manipulation, it will be interesting to determine whether autophagy is benefitting virus or host and whether its induction or inhibition favors either lytic or latent stages of infection.

Autophagy allows cells defective in apoptosis to survive metabolic stress for weeks (6, 24, 40, 44). Sustained autophagy in the face of prolonged nutrient deprivation causes cells to shrink in size, but alleviation of metabolic stress allows cells to recover. This reversibility is a hallmark of autophagy (22). While cell division is initially maintained under such conditions, eventually, cell proliferation and motility decrease and nutrient restoration no longer reverses cell deterioration (43). Though previously shown in tumor cells, this mechanism may also apply in the setting of virus infection as a means to prolong virus production.

In vivo, EC detachment is pertinent in a variety of disease settings, where insult to the vascular lining leads to EC sloughing. These resultant circulating ECs (CECs) serve as biomarkers for disease severity (19, 79). For example, CECs infected with the human γHV KSHV appear in the blood of Kaposi's sarcoma patients (55). Tethering of ECs to matrix by adhesive molecules is critical for maintenance of survival signals, and loss of these signals upon detachment triggers anoikis (52). Disturbance of these survival signals has been implicated in EC detachment caused by cytomegalovirus, and in general, viral infections appear to inhibit interaction of ECs with basement membrane proteins (58, 73). Whether or not detachment precedes either apoptosis or autophagy remains unclear. Autophagy can impart anoikis resistance to epithelial tumor cells (14, 37), and the KSHV FLIP can protect ECs from anoikis, providing precedent for γHV-specific efforts to promote survival of detached ECs (10).

We propose a model in which productive γHV68 infection of adherent cell types inherently results in cell detachment. While fibroblasts uniformly die in response to this infection, ECs survive matrix detachment. Initially, v-cyclin provides proliferative cues for detached cells, allowing maintenance of cell cycle and metabolism. Simultaneously, v-Bcl2 protects ECs from anoikis, potentially through manipulation of apoptosis and/or autophagy, and preserves the viability of infected cells. Consistent with autophagy-mediated cell preservation, disruption of productive virus infection allows phenotypic recovery of the surviving cells, with potential for these altered cells to recover and be propagated in vivo after conditions of transient immune suppression and restoration. In vivo, such disruption and continued viability could occur via restoration of immune surveillance, such as a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated mechanism, as shown in herpes simplex virus type 1 regulation of late gene synthesis in neurons (30).

Our data implicate manipulation of the autophagic machinery as a mechanism for promoting EC-specific survival of productive γHV68 infection. This outcome appears to be the result of a specific interaction between γHV68 and ECs, as it results in productive infection and is promoted by specific viral oncogenes. The ability of these persistently infected cells to survive substrate detachment confers the potential to traffic and deliver virus to distant sites. Furthermore, because these persistently infected cells express abundant virus proteins, they likely are highly immunogenic and inflammatory, consistent with the mixed morphology of γHV-associated endothelial and epithelial cell tumors. These persistently infected and immunogenic cells are likely to be effectively controlled in a healthy host but may contribute to disease under conditions of immune suppression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the following agencies: Burroughs Wellcome Fund; National Cancer Institute, NIH, CA103632; Predoctoral Training in Molecular Biology, NIH, T32-GM08730; Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F31 CA132561-01; and the Colorado Center for AIDS Research.

We thank Noboru Mizushima, Jayanta Debnath, Phillipa Marrack, Herbert Virgin, and Andrew Thorburn for their kind gifts of reagents. We thank Gary Mierau for providing his expertise regarding transmission electron microscopy. We are also grateful to Andrew Thorburn, Phillipa Marrack, and Eric Clambey for their critical reading of the manuscript, to Tony Desbien for technical expertise, and to Michelle Stewart for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blaskovic D., Stancekova M., Svobodova J., Mistrikova J. 1980. Isolation of five strains of herpesviruses from two species of free living small rodents. Acta Virol. 24:468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boya P., et al. 2005. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1025–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bridgeman A., Stevenson P. G., Simas J. P., Efstathiou S. 2001. A secreted chemokine binding protein encoded by murine gammaherpesvirus-68 is necessary for the establishment of a normal latent load. J. Exp. Med. 194:301–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clambey E. T., Virgin H. W., IV, Speck S. H. 2002. Characterization of a spontaneous 9.5-kilobase-deletion mutant of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reveals tissue-specific genetic requirements for latency. J. Virol. 76:6532–6544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Debnath J. 2009. Detachment-induced autophagy in three-dimensional epithelial cell cultures. Methods Enzymol. 452:423–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Degenhardt K., et al. 2006. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 10:51–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Lima B. D., May J. S., Marques S., Simas J. P., Stevenson P. G. 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 bcl-2 homologue contributes to latency establishment in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 86:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diebel K. W., Smith A. L., van Dyk L. F. Mature and functional viral miRNAs transcribed from novel RNA polymerase III promoters. RNA 16:170–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dirmeier U., et al. 2003. Latent membrane protein 1 is critical for efficient growth transformation of human B cells by Epstein-Barr virus. Cancer Res. 63:2982–2989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Efklidou S., Bailey R., Field N., Noursadeghi M., Collins M. K. 2008. vFLIP from KSHV inhibits anoikis of primary endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 121:450–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ehtisham S., Sunil-Chandra N. P., Nash A. A. 1993. Pathogenesis of murine gammaherpesvirus infection in mice deficient in CD4 and CD8 T cells. J. Virol. 67:5247–5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisenberg-Lerner A., Bialik S., Simon H. U., Kimchi A. 2009. Life and death partners: apoptosis, autophagy and the cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ. 16:966–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frisch S. M. 1999. Methods for studying anoikis. Methods Mol. Biol. 129:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fung C., Lock R., Gao S., Salas E., Debnath J. 2008. Induction of autophagy during extracellular matrix detachment promotes cell survival. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:797–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gangappa S., van Dyk L. F., Jewett T. J., Speck S. H., Virgin H. W., IV 2002. Identification of the in vivo role of a viral bcl-2. J. Exp. Med. 195:931–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonzalez-Polo R. A., et al. 2005. The apoptosis/autophagy paradox: autophagic vacuolization before apoptotic death. J. Cell Sci. 118:3091–3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gould F., Harrison S. M., Hewitt E. W., Whitehouse A. 2009. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus RTA promotes degradation of the Hey1 repressor protein through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. J. Virol. 83:6727–6738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang E. S. 1975. Human cytomegalovirus. IV. Specific inhibition of virus-induced DNA polymerase activity and viral DNA replication by phosphonoacetic acid. J. Virol. 16:1560–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hunting C. B., Noort W. A., Zwaginga J. J. 2005. Circulating endothelial (progenitor) cells reflect the state of the endothelium: vascular injury, repair and neovascularization. Vox Sang. 88:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jin S., DiPaola R. S., Mathew R., White E. 2007. Metabolic catastrophe as a means to cancer cell death. J. Cell Sci. 120:379–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jin S., White E. 2007. Role of autophagy in cancer: management of metabolic stress. Autophagy 3:28–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin S., White E. 2008. Tumor suppression by autophagy through the management of metabolic stress. Autophagy 4:563–566 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jordan M., Schallhorn A., Wurm F. M. 1996. Transfecting mammalian cells: optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karantza-Wadsworth V., et al. 2007. Autophagy mitigates metabolic stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 21:1621–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaye K. M., Izumi K. M., Kieff E. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:9150–9154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kilger E., Kieser A., Baumann M., Hammerschmidt W. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which simulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J. 17:1700–1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimura S., Noda T., Yoshimori T. 2007. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3:452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klionsky D. J., et al. 2008. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4:151–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klionsky D. J., et al. 2003. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev. Cell 5:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knickelbein J. E., et al. 2008. Noncytotoxic lytic granule-mediated CD8+ T cell inhibition of HSV-1 reactivation from neuronal latency. Science 322:268–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ku B., et al. 2008. Structural and biochemical bases for the inhibition of autophagy and apoptosis by viral BCL-2 of murine gamma-herpesvirus 68. PLoS Pathog. 4:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ku B., et al. 2008. An insight into the mechanistic role of Beclin 1 and its inhibition by prosurvival Bcl-2 family proteins. Autophagy 4:519–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kundu M., Thompson C. B. 2008. Autophagy: basic principles and relevance to disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3:427–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee D. Y., Sugden B. 2008. The latent membrane protein 1 oncogene modifies B-cell physiology by regulating autophagy. Oncogene 27:2833–2842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee H. K., Lund J. M., Ramanathan B., Mizushima N., Iwasaki A. 2007. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science 315:1398–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee K. S., Cool C. D., van Dyk L. F. 2009. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection of gamma interferon-deficient mice on a BALB/c background results in acute lethal pneumonia that is dependent on specific viral genes. J. Virol. 83:11397–11401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lock R., Debnath J. 2008. Extracellular matrix regulation of autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20:583–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loh J., et al. 2005. A surface groove essential for viral Bcl-2 function during chronic infection in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 1:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lois C., Hong E. J., Pease S., Brown E. J., Baltimore D. 2002. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science 295:868–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lum J. J., et al. 2005. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell 120:237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maiuri M. C., et al. 2007. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-X(L) and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 26:2527–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marelli-Berg F. M., Peek E., Lidington E. A., Stauss H. J., Lechler R. I. 2000. Isolation of endothelial cells from murine tissue. J. Immunol. Methods 244:205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mathew R., Karantza-Wadsworth V., White E. 2007. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mathew R., et al. 2007. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 21:1367–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. May D., et al. 2008. Transgenic system for conditional induction and rescue of chronic myocardial hibernation provides insights into genomic programs of hibernation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:282–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meredith J. E., Jr., Fazeli B., Schwartz M. A. 1993. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol. Biol. Cell 4:953–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mitchell T. C., et al. 2001. Immunological adjuvants promote activated T cell survival via induction of Bcl-3. Nat. Immunol. 2:397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Matsui M., Yoshimori T., Ohsumi Y. 2004. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1101–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mizushima N., Yoshimori T. 2007. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy 3:542–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moore S. A., Prokuski L. J., Figard P. H., Spector A. A., Hart M. N. 1988. Murine cerebral microvascular endothelium incorporate and metabolize 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. J. Cell. Physiol. 137:75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moorman N. J., Virgin H. W., IV, Speck S. H. 2003. Disruption of the gene encoding the gammaHV68 v-GPCR leads to decreased efficiency of reactivation from latency. Virology 307:179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Oguey D., George P. W., Ruegg C. 2000. Disruption of integrin-dependent adhesion and survival of endothelial cells by recombinant adenovirus expressing isolated beta integrin cytoplasmic domains. Gene Ther. 7:1292–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pankiv S., et al. 2007. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282:24131–24145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pattingre S., et al. 2005. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122:927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pellet C., et al. 2006. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126:621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Roy D. J., Ebrahimi B. C., Dutia B. M., Nash A. A., Stewart J. P. 2000. Murine gammaherpesvirus M11 gene product inhibits apoptosis and is expressed during virus persistence. Arch. Virol. 145:2411–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sarkar S., Davies J. E., Huang Z., Tunnacliffe A., Rubinsztein D. C. 2007. Trehalose, a novel mTOR-independent autophagy enhancer, accelerates the clearance of mutant huntingtin and alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 282:5641–5652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Scholz M., Blaheta R. A., Vogel J., Doerr H. W., Cinatl J., Jr 1999. Cytomegalovirus-induced transendothelial cell migration. A closer look at intercellular communication mechanisms. Intervirology 42:350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]