Abstract

Hepatitis C NS3/4A protease is a prime therapeutic target that is responsible for cleaving the viral polyprotein at junctions 3-4A, 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B and two host cell adaptor proteins of the innate immune response, TRIF and MAVS. In this study, NS3/4A crystal structures of both host cell cleavage sites were determined and compared to the crystal structures of viral substrates. Two distinct protease conformations were observed and correlated with substrate specificity: (i) 3-4A, 4A4B, 5A5B, and MAVS, which are processed more efficiently by the protease, form extensive electrostatic networks when in complex with the protease, and (ii) TRIF and 4B5A, which contain polyproline motifs in their full-length sequences, do not form electrostatic networks in their crystal complexes. These findings provide mechanistic insights into NS3/4A substrate recognition, which may assist in a more rational approach to inhibitor design in the face of the rapid acquisition of resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a genetically diverse member of the genus Hepacivirus of the Flaviviridae family and infects over 180 million people worldwide (33). HCV contains a positive, single-stranded RNA genome that is translated as a single polyprotein along the endoplasmic reticulum by host cell machinery. The viral polyprotein is subsequently processed by host cell and viral proteases into structural (C, E1, and E2) and nonstructural (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) components (23). The NS3/4A protein, a bifunctional protease/helicase enzyme formed by the noncovalent association of NS3 and NS4A, hydrolyzes four known sites along the viral polyprotein, thereby liberating nonstructural proteins essential for viral replication. Previous kinetic data suggest that the first cleavage event at junction 3-4A occurs in cis as a unimolecular process, while processing of the remaining junctions 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B occurs bimolecularly in trans (2, 22). Interestingly, these data demonstrated that the NS4A sequence is essential for the cleavage of junction 4B5A. These viral substrates share little sequence similarity except for an acid at P6, cysteine or threonine at P1, and serine or alanine at P1′ (Table 1). Previous work by our group has revealed that the diverse set of NS3/4A substrate sequences are recognized in a conserved three-dimensional shape, defining a consensus van der Waals volume, or substrate envelope (29). This conserved mode of substrate recognition regulates polyprotein processing and thus the biology of HCV replication.

Table 1.

Primary cleavage sequences of NS3/4A substrates (genotype 1a)

| Substrate | Amino acid at position: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P6 | P5 | P4 | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | P2′ | P3′ | P4′ | |

| TRIF | P(8) | S | S | T | P | C | S | A | H | L |

| MAVS | E | R | E | V | P | C | H | R | P | S |

| 3-4A | D | L | E | V | V | T | S | T | W | V |

| 4A4B | D | E | M | E | E | C | S | Q | H | L |

| 4B5A | E | C | T | T | P | C | S | G | S | W |

| 5A5B | E | D | V | V | C | C | S | M | S | Y |

In addition to its essential role in processing the viral polyprotein, NS3/4A protease also confounds the innate immune response to viral infection by disrupting activation of the transcription factors interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (13, 21). Upon the detection of viral RNA in host cells, these transcription factors are induced through two distinct pathways involving signaling through Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) or retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) (1, 37). NS3/4A protease disrupts the TLR3 and RIG-I cascades by cleaving the essential adaptor proteins Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing beta interferon (TRIF) and mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), respectively (12, 21). The TRIF and MAVS cleavage sites share little sequence homology with other viral substrates: TRIF contains cysteine at P1 and serine at P1′, while MAVS contains glutamate at P6 and cysteine at P1 (Table 1). Notably, in place of an acid at position P6, TRIF consists of a track of eight proline residues spanning P13 to P6, which has been previously implicated as part of the substrate recognition motif for NS3/4A (11). The NS3-mediated processing of both viral and host cell targets is central to the interplay between HCV replication and the innate immune response, thus highlighting the importance of better elucidating the mechanisms of substrate recognition.

Despite great efforts devoted to the development of NS3/4A protease inhibitors, the rapid rise of drug resistance in human clinical trials has limited the efficacy of the most promising drug candidates. Drug resistance mutations in the protease emerge as molecular changes that prevent the binding of drugs but still permit the recognition and cleavage of substrates. A more detailed understanding of the molecular details underlying substrate recognition is therefore critical for explaining patterns of drug resistance and for designing novel drugs that are less susceptible to resistance. Here we analyze crystal structures of NS3/4A protease in complex with N-terminal products of viral substrates 3-4A, 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B. TRIF and MAVS crystal complexes further reveal that these host cell products bind to the protease active site in a conserved three-dimensional manner similar to that of the viral products. Notably, extensive electrostatic networks involving protease residues D81, R155, D168, and R123 form in product complexes 3-4A, 4A4B, 5A5B, and MAVS, while these networks are absent in the 4B5A and TRIF product complexes. Short peptides corresponding to the immediate cleavage sequences of TRIF and 4B5A have significantly weaker affinities for NS3/4, which correlate with their inability to form such electrostatic networks with the protease. Taken together, our findings support previous biochemical studies indicating a role of polyproline II helices in TRIF cleavage by NS3/4A (11) and provide a structural basis for future studies aimed at better elucidating the detailed mechanism of NS3/4A substrate recognition and cleavage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis and gene information.

The HCV genotype 1a NS3/4A protease gene described in a Bristol-Meyers Squibb patent (34) was synthesized by GenScript and cloned into the pET28a expression vector (Novagen). The gene encodes a highly soluble form of the NS3/4A protease domain as a single chain, with 11 core amino acids of NS4A located at the N terminus. The inactive S139A protease variant and SI39A/KI36A double mutant were subsequently constructed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene and sequenced by Davis Sequencing for confirmation.

Viral substrate and peptide product purchase and storage.

Thirty milligrams of each substrate peptide and the corresponding N-terminal cleavage product (TRIF and MAVS) were purchased from 21st Century Biochemicals (Marlboro, MA). The TRIF and MAVS peptides were synthesized as a 13-mer (P13 to P1) and a 7-mer (P7 to P1), respectively. The N termini of all peptides were acetylated. All peptides were stored as solids at −20°C and dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) to a final concentration of 50 to 100 mM for crystallization trials.

Expression and purification of NS3/4A protease constructs.

NS3/4A expression and purification were carried out as described previously (14, 34). Briefly, transformed Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells were grown at 37°C and induced at an optical density of 0.6 by the addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Cells were harvested after 5 h of expression, pelleted, and frozen at −80°C for storage. Cell pellets were thawed, resuspended in 5 ml/g of resuspension buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol [β-ME]), and lysed with a cell disruptor. The soluble fraction was retained, applied to a nickel column (Qiagen), washed with resuspension buffer, and eluted with resuspension buffer supplemented with 200 mM imidazole. The eluant was dialyzed overnight (molecular mass cutoff, 10 kDa) to remove the imidazole, and the His tag was simultaneously removed with thrombin treatment. The nickel-purified protein was then flash-frozen and stored at −80°C for up to 6 months.

Crystallization of product complexes and apoenzyme.

For crystallization, the protein solution was thawed, concentrated to ∼3 mg/ml, and loaded on a HiLoad Superdex75 16/60 column equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (25 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES] at pH 6.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 30 μM zinc chloride, and 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). The protease fractions were pooled and concentrated to 20 to 25 mg/ml with an Amicon Ultra-15 10-kDa device (Millipore). The concentrated samples were either used for crystallization of the apoenzyme structure or incubated for 1 h with a 2 to 20 molar excess of substrate product TRIF or MAVS. Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained overnight by mixing equal volume of concentrated protein solution with precipitant solution (20 to 26% polyethylene glycol [PEG] 3350, 0.1 M sodium MES buffer at pH 6.5, and 4% ammonium sulfate) in 24-well VDX hanging-drop trays.

Data collection and structure solution.

Crystals large enough for data collection were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage. The apoenzyme, TRIF, and MAVS crystals were mounted under a constant cryostream, and X-ray diffraction data were collected at Advanced Photon Source LS-CAT 21-ID-F, BioCARS 14-BMC, and our in-house RAXIS IV X-ray system, respectively. Diffraction intensities of product complexes were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the program HKL2000 (27). All structure solutions were generated using simple isomorphous molecular replacement with PHASER (24). The B-chain model of viral substrate product 4A4B (3M5M) (29) was used as the starting model for all structure solutions. Initial refinement was carried out in the absence of modeled ligand, which was subsequently built in during later stages of refinement. Upon obtaining the correct molecular replacement solutions, the phases were improved by building solvent molecules using ARP/wARP (25). Subsequent crystallographic refinement was carried out within the CCP4 program suite with iterative rounds of TLS and restrained refinement until convergence was achieved (6). The final structures were evaluated with MolProbity (7) prior to deposition in the Protein Data Bank. Five percent of the data was reserved for the free R-value calculation to limit the possibility of model bias throughout the refinement process (4). Interactive model building and electron density viewing were carried out using the program COOT (10).

Double-difference plots and global analysis.

Double-difference plots were computed as described previously (28). Briefly, the atomic distances between each Cα of a given protease molecule and every other Cα in the same molecule were calculated. The differences of these Cα-Cα distances between each pair of protease molecules were then calculated and plotted as a contour graph for visualization. These analyses allowed for effective structural comparisons without the biases associated with superimpositions and space group differences. Double-difference plots were used to determine the structurally invariant regions of the protease, consisting of residues 32 to 36, 42 to 47, 50 to 54, 84 to 86, and 140 to 143. Structural superimpositions were carried out in PyMOL (9) using the Cα atoms of these residues for all protease molecules. The apoenzyme structure was used as the reference structure for the alignments of the TRIF and MAVS product complexes. The Cα root mean square deviation (RMSD) for each residue was subsequently calculated to assess the degree of structural variation throughout the protein. The B-factor column of a representative structure was replaced with these values and used to generate the rainbow color spectrum to visualize these variations.

Viral substrate envelope.

All active-site alignments were performed with PyMOL using the Cα atoms of protease residues 137 to 139 and 154 to 160. For each alignment, the B chain of complex 4A4B was used as the reference structure. The NS3/4A viral substrate envelope, representing the consensus van der Waals volume shared by any three of the four viral substrate products, was computed as described previously using the full-length NS3/4A structure (1CU1) (35) and product complexes 4A4B (3M5M), 4B5A (3M5N), and 5A5B (3M5O) (29). Active-site comparisons of the four NS3/4A viral product complexes were performed by superposition the Cα atoms of residues 137 to 139 and 154 to 160, revealing that both the active-site residues and substrate products spanning P6 to P1 align closely, with average Cα RMSDs of 0.24 Å and 0.35 Å, respectively.

NMR spectroscopy and data processing.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data were recorded using 650 μl of 390 μM [U-15N]NS3/4A protease [95% H2O/5% D2O, 25 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.2, 150 mM KCl, 5 μM zinc chloride, and 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)]. Backbone 1H and 15N resonance assignments for NS3/4A protease were kindly provided by Herbert Klei of Bristol-Myers Squibb and were confirmed using nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments. Backbone 1H and 15N resonance assignments of NS3/4A protease bound to the N-terminal cleavage product of substrate 4A4B were obtained from the assignment of the free protein by following the chemical shift changes upon titration of the ligand. All experiments were performed at 298 K using a Varian Inova spectrometer operating at 600 MHz (14.1 T). Spectra were processed using nmrPipe (8) and Sparky (15).

Binding of the unlabeled peptide corresponding to the N-terminal cleavage product of substrate 4A4B to [U-15N]NS3/4A protease was monitored using a series of two-dimensional 15N-1H heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra collected at increasing concentrations of the peptide to a final concentration of 2.5 mM. The change of the cross-peak positions for NS3/4A residues was recorded as a function of titrated peptide concentration. The normalized change in the chemical shift was calculated for each protease residue using the equation , where Δδ is the chemical shift change observed between the free and bound states, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, and the subscript indicates either 1H or 15N nuclei. The b factors for each residue of the apoenzyme crystal structure were then replaced by the maximal chemical shift changes from the titration data. The crystal structure was colored in PyMOL (9) according to the chemical shift magnitudes to graphically depict the locations of the shifting residues.

van der Waals contact energy.

van der Waals contact energies between protease residues and peptide products were computed using a simplified Lennard-Jones potential as described previously (26). Briefly, the Lennard-Jones potential (Vr) was calculated for each protease-product atom pair, where r, ε, and σ represent the interatomic distance, van der Waals well depth, and atomic diameter, respectively: Vr = 4ε[(σ/r)12 − (σ/r)6]. Vr was computed for all possible protease-product atom pairs within 5 Å, and potentials for nonbonded pairs separated by less than the distance at the minimum potential were equated to −ε. Using this simplified potential value for each nonbonded protease-product atom pair, the total van der Waals contact energy (ΣVr) was computed for each peptide residue. For graphical convenience, van der Waals energy indexes were then calculated by multiplying the raw values by a factor of −10.

Fluorescence polarization.

For fluorescence polarization experiments, the NS3/4A protease domain was purified in purification buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 4 mM DTT) as described above and subsequently concentrated to 200 to 400 μM. The concentrated stocks were then two-thirds serially diluted in 384-well plates (Corning) in reaction buffer using the Genesis workstation (Tecan). An equal volume of substrate buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 20% glycerol, 4 mM DTT) containing 10 nM fluorescein-tagged substrate product (4A4B, 4B5A, or 5A5B) was added to each well to make a final well volume of 60 μl. The final condition constituted 5 nM fluorescein-tagged cleavage products in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 75 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, and 4 mM DTT. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 2 h, and five fluorescence polarization measurements were taken for each well using the Victor-3 plate reader (Perkin-Elmer). Five sets of binding data were collected for each substrate product, and each trial was processed independently. The averages and standard deviations were then calculated from the results of these five trials. Fluorescence polarization data (in milli-polarization units [mP]) were fit to the Hill equation, where ET is the total NS3/4A concentration, Kd is the equilibrium binding constant, b is the baseline fluorescence polarization, and m is the fluorescence polarization maximum: mP = b + (m − b)[ET/(ET + Kd)].

RESULTS

Structure determination of apo-NS3/4A and product complexes.

The apo-NS3/4A protease domain and host cell product complexes TRIF and MAVS all crystallized in the space group P212121 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Table 2). For all structures, we utilized the highly soluble NS3/4A protease domain described previously, containing the essential residues of cofactor NS4A covalently linked at the N terminus (34). This NS3/4A construct also contains the inactivating mutation S139A, which is designed to further enhance protein stability by minimizing autoproteolysis during the crystallization process. The partially inactivated variant still exhibits residual proteolytic activity, as observed for other serine proteases (5, 18), likely facilitated by the nucleophilic attack of water. Thus, the complete characterization of full-length substrate peptides was not possible, and short peptides corresponding to the N-terminal cleavage products of authentic substrates were used for all crystallization trials. Peptide products 4A4B, 4B5A, 5A5B, and MAVS spanned P7 to P1, while the TRIF sequence spanned P13 to P1 with a track of eight proline residues at the N terminus (Table 1). The entire peptide sequence spanning P7 to P1 could be modeled in each structure except for the TRIF complex, which revealed electron density for the residues spanning P6 to P1 but not the polyproline track.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parametera | Valueb for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIF | MAVS | Apo-NS3/4A | |

| Protein Data Bank no. | 3RC4 | 3RC5 | 3RC6 |

| Modeled ligand | PSSTPC | QEREVPC | (Unliganded) |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.50 (1.50–1.55) | 1.60 (1.60–1.66) | 1.30 (1.30–1.35) |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Molecules in asymmetric unit | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | |||

| a | 53.9 | 54.1 | 54.8 |

| b | 58.1 | 58.2 | 58.6 |

| c | 61.3 | 61.3 | 60.9 |

| Completeness (%) | 87.4 (93.1) | 99.3 (99.1) | 93.1 (97.1) |

| Total reflections | 136929 | 97504 | 190364 |

| Unique reflection | 27770 | 26041 | 45595 |

| Avg I/σ | 13.5 (4.4) | 18.8 (5.4) | 14.8 (4.1) |

| Redundancy | 4.9 (4.7) | 3.7 (3.7) | 4.2 (4.0) |

| Rsym (%) | 4.8 (30.1) | 3.3 (19.3) | 4.1 (29.3) |

| RMSD | |||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Angles (°) | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.29 |

| Rfactor (%) | 18.7 | 17.3 | 16.2 |

| Rfree (%) | 21.5 | 19.3 | 19.1 |

Rsym = Σ|I − 〈I〉|/ΣI, where I = observed intensity and 〈I〉 = average intensity over symmetry equivalent. Rwork = Σ‖Fo| − |Fc‖/Σ|Fo|. Rfree was calculated from 5% of reflections, chosen randomly, which were omitted from the refinement process.

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Tertiary structure analysis.

Structural analyses of the NS3/4A apoenzyme were carried out in conjunction with (i) the host cell product complexes TRIF and MAVS, (ii) the viral product complexes 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B (29), and (iii) the full-length NS3/4A structure (35), in which the C terminus represents the postcleavage product 3-4A. The seven structures constitute a total of 12 NS3/4A protease monomers, which all adopt the same chymotrypsin-like tertiary fold defined by the labeling scheme for trypsin (3). The N-terminal distorted β-barrel subdomain contains two α helices (α0 and α1) and seven β strands (A0 to F1), while the C-terminal β-barrel subdomain comprises two α helices (α2 and α3) and six β strands (A2 to F2). The cofactor NS4A contributes a single β strand to the N-terminal distorted β barrel, which is essential for efficient catalytic function (22). The catalytic triad is located in the cleft between these subdomains, with the N-terminal β barrel contributing residues H57 and D81 and the C-terminal β barrel contributing the nucleophilic S139. The active-site residues in all crystal structures share a similar architecture, defined by the catalytic triad residues (S139A, H57, and D81) and backbone nitrogens of the oxyanion hole (G137, S138, and S139A).

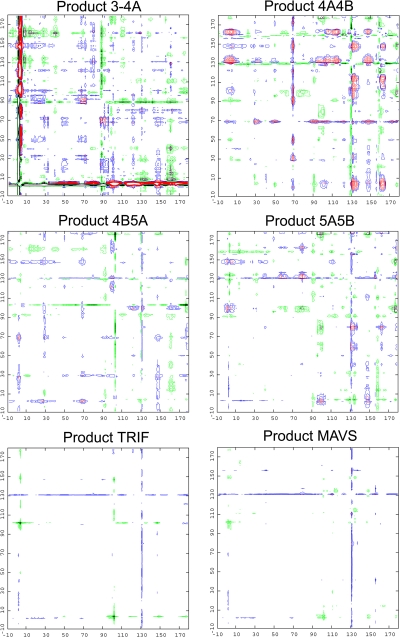

Certain global differences are observed between these structures when superpositions are performed. Double-difference plots between each cocomplex and the apoenzyme were therefore generated to determine the most invariant regions (Fig. 1). Product 3-4A varied most extensively from the apo state, which likely reflects differences in genotype, protein size, and crystal packing of the full-length construct. The remaining product complexes derive from the same NS3/4A protease domain construct and, in general, vary less extensively from the apoenzyme. Notably, the host cell product complexes are most similar to the apoenzyme, while viral product complexes 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B vary more extensively. Taken together, these findings suggest that structural differences likely reflect the inherent flexibility in certain regions of the protease.

Fig. 1.

Double-difference plots of product complexes. Double-difference plots were computed for viral and host cell product complexes relative to the apoenzyme structure. NS3 protease residues are numbered according to the conventional system, whereas negative numbers indicate residues of the cofactor NS4A. Red and blue contour lines represent positive differences of 1.0 Å and 0.5 Å, respectively, while black and green lines represent negative differences of the same magnitudes.

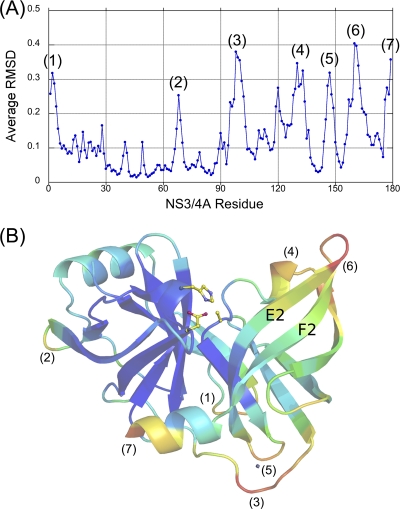

The set of double-difference plots was further analyzed, and the most invariant regions of the protease were determined to contain residues 32 to 36, 42 to 47, 50 to 54, 84 to 86, and 140 to 143 (Fig. 1). Product complexes 4A4B, 4B5A, 5A5B, TRIF, and MAVS consist of 10 protease molecules, which were subsequently superposed onto the apoenzyme using the Cα atoms of the structurally invariant residues. The Cα average root mean square deviation (RMSD) was calculated for each residue, and the seven most variable regions of the protease (Fig. 2A) were determined to be (i) the linker connecting cofactor 4A at the N terminus, (ii) the loop containing residues 65 to 70, (iii) the zinc-binding site containing residues 95 to 105, (iv) the 310 helix region spanning residues 128 to 136, (v) the zinc-binding site containing residues 145 to 148, (vi) the active-site antiparallel β sheet containing residues 156 to 168, and (vii) the C-terminal α3 helix. These regions are solvent exposed and likely influenced by both crystal packing effects and inherent flexibility.

Fig. 2.

Average RMSDs of product complexes. All protease molecules from product complexes 4A4B, 4B5A, 5A5B, TRIF, and MAVS were superposed onto the apoenzyme structure using the most invariant core residues 32 to 36, 42 to 47, 50 to 54, 84 to 86, and 140 to 143. The average Cα RMSDs were plotted versus residue number (A) and mapped onto a representative protease molecule with the most variable regions depicted in red and the most invariant regions depicted in blue (B). The seven most variable regions of the protease are labeled in both panels.

Extensive structural differences are observed near the active site as indicated by large RMSDs for residues 156 to 168. These differences are most pronounced for the β strands E2 and F2, which form the antiparallel β sheet constituting the majority of the active site. This region is least variable near the catalytic triad, while the average RMSDs increase significantly toward the loop connecting these β strands (Fig. 2B). Though the architecture of the protease catalytic triad is conserved, these observations suggest a potential dynamic interaction between the antiparallel β sheet of the protease active site and substrate products. Further studies are necessary to probe the nature and extent of such dynamic interplay. Nevertheless, though the Cα atoms of active-site residues shift relative to the protease core, these residues superpose well onto the apoenzyme with a RMSD range of 0.3 to 0.5Å. Moreover, the residue side chains adopt similar rotamer conformations and interact with the same surrounding residues, suggesting that potential flexibility in the protease active site would not disrupt its tertiary structure.

Analysis of viral product binding.

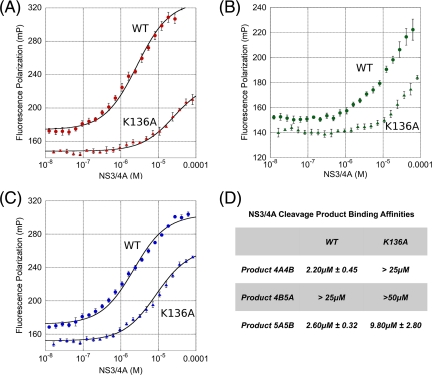

Fluorescence polarization experiments reveal that the viral products bind with different affinities to the protease, with the Kd for 4B5A over 10-fold weaker than those for 4A4B and 5A5B (Fig. 3). Crystal structures reveal that these viral products bind in a conserved manner, forming an anti parallel β sheet with protease residues 154 to 160 and burying 500 to 600 Å2 of solvent-accessible surface area (19). The peptide product backbone torsion angles are very similar, with positions P1 to P4 being the most similar and residues P5 to P7 deviating progressively toward the C terminus. A constrained P2 φ torsion angle of about −60° is observed in product complexes 3-4A, 4A4B, and 5A5B. Interestingly, these P2 residues could sterically tolerate the substitution of proline, which is found at the P2 position in substrates 4B5A, TRIF, and MAVS. The ability of the P2 residue to adopt this constrained backbone torsion is a likely determinant in the recognition process, allowing for the proper positioning of the P1 cysteine for catalysis in the active site.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence polarization of viral product binding. (A to C) Fluorescence polarization binding experiments were conducted with the inactive S139A protease (wild type [WT]) (circles) and the S139A/K136A variant (triangles) with fluorescein-tagged peptide products 4A4B (A), 4B5A (B), and 5A5B (C). For all conditions, trace amounts of peptide were incubated for 2 h with increasing concentrations of NS3/4A protease in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 75 mM potassium chloride, 20% glycerol, 0.5 μM zinc chloride, and 4 mM DTT. Each panel depicts a single representative trial, though the reaction for each condition was repeated five times. (D) Data for each trial were processed independently by least-squares regression fitting with the Hill equation, and the averages and standard deviations of equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated.

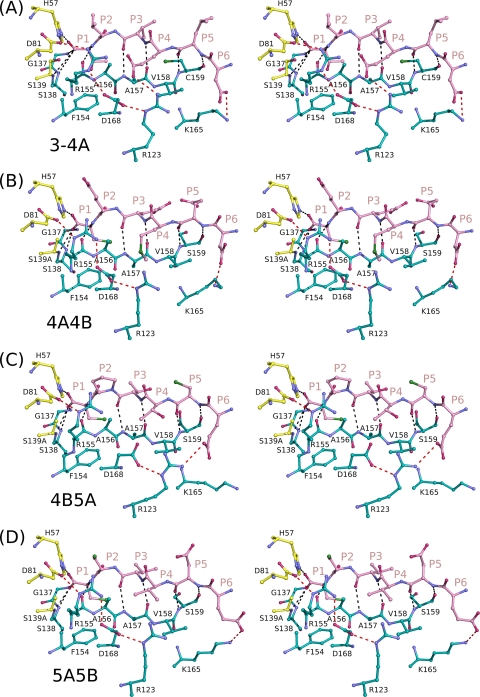

There are many conserved features in viral product binding, involving both backbone and side chain interactions (Fig. 4). For example, eight hydrogen bonds between backbone amide and carbonyl groups are completely conserved in the product complexes, involving protease residues G137, S138, S139A, R155, A157, and S159. S159 (C159 in product complex 3-4A) and A157 each contribute two hydrogen bonds with bound products at positions P5 and P3, respectively. The P1 residue, which is cysteine in all substrates but 3-4A, interacts favorably with the π system of electrons of F154. All P1 terminal carboxyl groups sit in the oxyanion hole, hydrogen bonding with the Nε nitrogen of H57 and the amide nitrogens of residues 137 to 139. Though the coordinates of the P1 terminal oxygen atom are not included in the full-length NS3/4A structure, geometric restraints would position it similarly to the other peptide products. Thus, the same set of protease residues contacts all peptide sequences, although the precise nature of these interactions varies depending on the particular residue involved in each contact.

Fig. 4.

Stereo view of viral product binding to NS3/4A protease. N-terminal NS3/4A cleavage products 3-4A (A), 4A4B (B), 4B5A (C), and 5A5B (D) are shown binding to the protease active site, with the electrostatic interactions of backbone and side chain atoms depicted in black and red, respectively.

Despite these similarities, there are also unique features that likely underlie the particular specificity of NS3/4A for each substrate (Fig. 4). For example, the four acidic residues in product 4A4B lead to a highly charged peptide in solution. In the bound state, however, the atomic geometry suggests that the P5 glutamate is protonated and hydrogen bonding with the carboxyl group of the P3 glutamate, which itself forms an ionic interaction with the terminal nitrogen of K136. In fact, K136 interacts differently with all four viral products, forming (i) a hydrogen bond with the P2 carbonyl oxygen of 3-4A, (ii) a salt bridge with the P3 glutamate of 4A4B, and (iii) an extended conformation that does not interact considerably in product complexes 4B5A and 5A5B. Fluorescence polarization data confirm a more significant loss in binding affinity of product 4A4B for the K136A protease variant than of products 4B5A and 5A5B (Fig. 3). Thus, the affinity of a substrate product likely arises from the side chain interactions unique to that particular product.

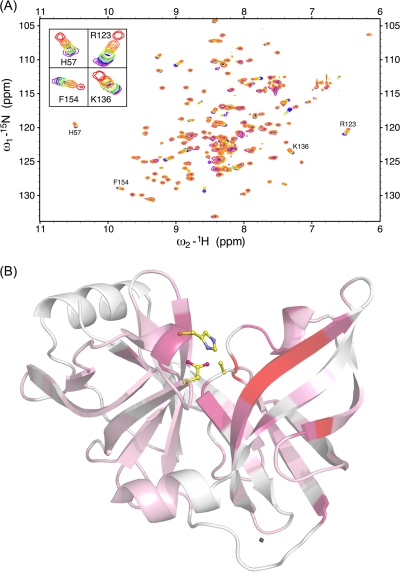

NMR solution studies of product 4A4B binding.

The NS3/4A protease active site is located on the surface of the protein and thus is highly solvent exposed. The analysis of viral and host cell product binding is therefore complicated by the proximity of symmetry-related molecules within the crystal lattice. To investigate the possibility of crystal packing effects confounding structural observations, we carried out NMR HSQC titration experiments using peptide product 4A4B spanning P7 to P1 (Fig. 5A). HSQC chemical shift perturbations upon product titration are consistent with the molecular interactions observed in the crystal complex. The normalized chemical shift perturbations for each protease residue were compared to the buried surface area calculated directly from product complex 4A4B (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the same set of protease residues with large chemical shift perturbations also interact extensively with product 4A4B in the crystal structure. The NMR solution studies recapitulate our structural observations and suggest that our crystal structure analyses are indeed representative of the interactions occurring in solution.

Fig. 5.

NS3/4A 1H, 15N NMR HSQC titration data. (A) NMR spectra reveal 15N-labeled NS3/4A chemical shift perturbations upon titration of increasing concentrations of substrate 4A4B product peptide. Cross-peaks are colored according to the concentration of peptide product 4A4B, ranging from 0 mM (blue) to 2.5 mM (red). For clarity, the titration data for the highest peptide concentration (2.5 mM) are depicted only in the insets. (B) The apo-NS3/4A crystal structure was colored according to the chemical shift changes between the apoenzyme state and 2.5 mM product 4A4B. Protease residues undergoing chemical shifts are colored by a spectrum ranging from pink (small shifts) to red (large shifts). All unassigned residues are depicted in white.

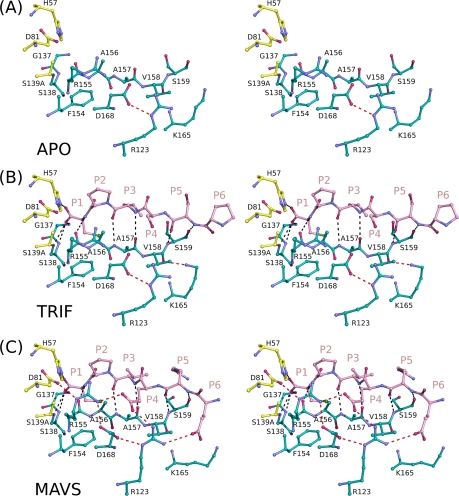

Analysis of host cell product complexes TRIF and MAVS.

Active-site superpositions (residues 137 to 139 and 154 to 160) reveal that TRIF and MAVS peptide products both bind to the protease active site in a conserved three-dimensional shape (Fig. 6). Both substrate products form antiparallel β sheets with protease residues 154 to 160. There is no clear electron density in the TRIF complex for the proline residues spanning P13 to P7. Nevertheless, the residues from P6 to P1 overlap closely with the corresponding residues in the MAVS complex. The P1 cysteine residues of both substrate products interact with the aromatic ring of F154. Eight hydrogen bonds are observed in both structures, involving the amide nitrogens or carboxyl oxygens of residues G137, S138, S139A, R155, A157, and S159. A157 and S159 each contribute two hydrogen bonds with the P3 and P5 residues, respectively. In both structures, the carbonyl groups at position P1 interact with the protease oxyanion hole, defined by the backbone amide nitrogens of residues 137 to 139. Thus, the postcleavage products of the cellular substrates TRIF and MAVS bind to the protease active site in a conserved manner despite their large variations in primary sequence.

Fig. 6.

Stereo view of host cell product binding to NS3/4A protease. The apoenzyme structure (A) and N-terminal cleavage products TRIF (B) and MAVS (C) are shown binding to the protease active site, with the electrostatic interactions of backbone and side chain atoms depicted in black and red, respectively.

There are also many differences in the binding of TRIF and MAVS involving mainly side chain interactions with the protease (Fig. 6). For example, MAVS interacts closely with the protease electrostatic network formed by residues D81, R155, D168, and R123. The P4 glutamate of MAVS interacts with R155 and R123 in this network, while the P6 glutamate forms a salt bridge with R123. The TRIF peptide product, however, lacks such extended residues on this surface of the molecule, and the electrostatic network is notably absent, with the participating residues adopting conformations observed in the apoenzyme structure. Previous studies demonstrate that a large fraction of full-length TRIF exists as polyproline II helices and that the interaction of NS3/4A with a polyproline II helix facilitates TRIF cleavage (11). The absence of clear electron density for the proline residues suggests that full-length TRIF may be necessary to stabilize the polyproline track in a conformation capable of specific interaction with NS3/4A.

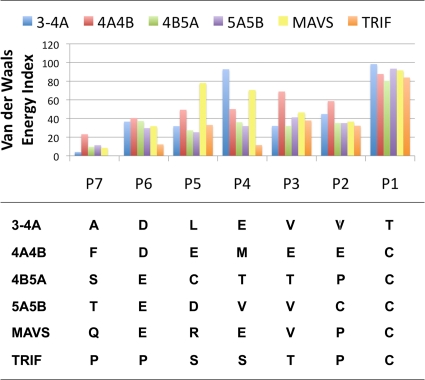

Comparison of host cell and viral product binding.

Host cell product binding was analyzed on a broader basis by comparison with the binding of viral substrates, previously reported by our group (29). Both viral (3-4A, 4A4B, 4B5A, and 5A5B) and host cell (TRIF and MAVS) substrate products bind to the protease active site in a conserved three-dimensional shape. The peptide backbone torsional angles are very similar, being most conserved at position P1 and deviating slightly toward position P6. All peptide products adopt constrained P2 Ψ torsion angles, even those containing nonproline residues at this site. However, van der Waals analyses of substrate products indicate large variations in side chain interactions with the protease. All of the NS3/4A substrates contain either cysteine or threonine at position P1, while five of the six contain an acid at position P6. The P1 and P6 substrate residues each contribute the same amount of van der Waals energies in all product complexes (Fig. 7). The amino acid makeup of viral cleavage sequences is much more diverse at positions P5 to P2, and in general, the van der Waals energies at each position correlate with amino acid size. For example, the P4 glutamates in substrates 3-4A and MAVS, and to a lesser extent the P4 methionine in substrate 4A4B, are associated with larger van der Waals energies than the substrates with smaller P4 residues. Likewise, the larger glutamate residues at both P3 and P2 of substrate 4A4B also correlate with greater contact energies than for the other substrates, which contain smaller amino acids at these positions.

Fig. 7.

van der Waals energies of viral substrate binding. The van der Waals binding energies for subsites P7 to P1 of each NS3/4A cleavage product (3-4A, 4A4B, 4B5A, 5A5B, TRIF, and MAVS) are graphically depicted, with their primary amino acid sequences tabulated at the bottom.

Though similar in shape, protease substrate binding can be further categorized into two groups: (i) product complexes 3-4A, 4A4B, 5A5B, and MAVS bind with an intact electrostatic network involving residues D81, R155, D168, and R123, while (ii) product complexes 4B5A and TRIF bind without this network such that R155, D168, and R123 maintain conformations observed in the apoenzyme. Notably, the 4B5A and TRIF cleavage sites contain fewer charged residues than the other substrates, which may underlie their inability to form the electrostatic network. Binding studies demonstrate that both 4B5A and TRIF have relatively weaker affinities for NS3/4A than the other substrates (11, 31). However, most biochemical studies have been conducted on small peptides corresponding to the immediate cleavage sequences of TRIF and 4B5A. Indeed, kinetic studies revealed that full-length TRIF is processed more efficiently than peptides corresponding to the cleavage sequence (11). Additional molecular interactions by the full-length proteins or by adaptor proteins in the authentic cellular environment may better facilitate substrate binding. Nevertheless, the current structural analyses suggest that NS3/4A substrates vary in specificity by their ability to form and stabilize the protease electrostatic network; the sequence specificity is particularly influenced by amino acid variation at positions P6, P4, and P2.

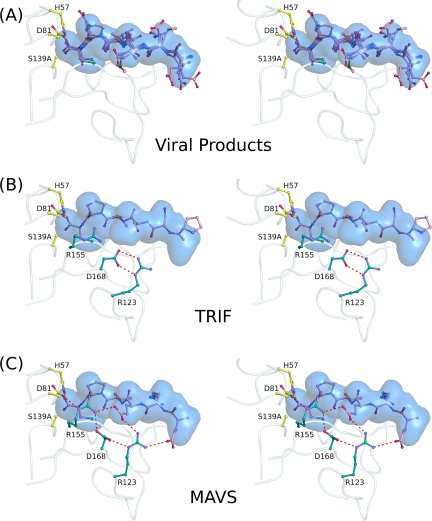

Analysis using the viral substrate envelope.

The binding of NS3/4A cellular substrates was analyzed in terms of the viral substrate envelope (Fig. 8), which was previously defined as the van der Waals volume shared by any three of four viral products (29). This shape could not be predicted by the primary sequences alone, which highlights the conserved mode of viral substrate recognition despite their high sequence diversity. The backbone chains of both TRIF and MAVS fit entirely within the substrate envelope, as well as the side chains of TRIF spanning P5 to P1. The side chains of MAVS are also mostly confined within the substrate envelope, except for the longer side chains of the P6 glutamate, P5 arginine, and P4 glutamate. The carboxylic acids of these glutamate residues interact extensively with the protease electrostatic network, while the P5 arginine packs against loop residues 159 to 162. As these interactions occur outside the viral substrate envelope, we speculate that mutations that disrupt the electrostatic network, such as R155K and D168A, would preferentially reduce the proteolytic processing of MAVS compared to TRIF.

Fig. 8.

Host cell product binding and the NS3/4A substrate envelope. (A) The NS3/4A substrate envelope is calculated from the consensus van der Waals volume shared by any three of the four viral products. (B) The TRIF cleavage product is largely confined within the substrate envelope. (C) MAVS is located mostly within the substrate envelope except for the side chain atoms spanning P6 to P4.

DISCUSSION

The recognition and proteolysis of the viral polyprotein and host cell adaptor proteins by NS3/4A protease play an integral role in the ability of HCV to replicate and evade the innate immune response to viral infection (12, 21). In this study, crystal structures of the NS3/4A protease domain revealed that viral and host cell products bind to the protease active site in similar three-dimensional shapes, defined by the viral substrate envelope reported previously (29). The MAVS product complex reveals the formation of an extensive electrostatic network involving protease residues D81, R155, D168, and R123, which also form in viral product complexes 3-4A, 4A4B, and 5A5B. No such networks form in the TRIF and 4B5A complexes, and residues in this region of the protease adopt the same conformations observed in the apo state. The absence or presence of electrostatic networks also correlates with the affinities of product binding, with the Kd of 4B5A being 10-fold weaker than those of products 4A4B and 5A5B. The greater catalytic efficiencies of NS3/4A for substrates 4A4B and 5A5B relative to 4B5A (31) may also derive from the formation of electrostatic networks. However, a short peptide may only partially mimic how the viral cleavage sequences are processed along the viral polyprotein in the natural cellular environment. Additional molecular features may further modulate the binding of TRIF and 4B5A, perhaps facilitated by the proline-rich regions contained in both proteins (11). Thus, the specificity of substrate processing by NS3/4A protease seems to arise from at least two distinct molecular interaction patterns, which likely influence the order and kinetics of polyprotein processing during the HCV life cycle.

In fact, these structural observations can be further linked to the known biology of NS3/4A processing during viral replication. Previous NS3-mediated cleavage assays of HCV polyprotein substrates revealed that NS4A is essential for the trans cleavage of junction 4B5A but is not required for the processing of junctions 4A4B and 5A5B (2, 22). Our structural analyses provide further insight into the molecular interactions underlying these previous findings. The NS4A cofactor likely stabilizes the tertiary protease fold required for the binding of NS3/4A substrates, and the binding of substrate 4B5A may absolutely depend on this particular protease conformation. Substrates 4A4B and 5A5B, however, may be able to induce these conformational changes through charge interactions, even in the absence of cofactor NS4A. Thus, our findings support the previous published data for NS3 HCV polyprotein processing, and future research is warranted to better ascertain the dynamic mechanisms of substrate recognition.

The ability of HCV to establish chronic human infections is highly dependent on the ability of the virus to effectively replicate while simultaneously evading the host cell immune response. The virally encoded NS3/4A protein plays an integral role in this process by mediating the cleavage of essential viral proteins and antiviral host cell adaptors. NS3/4A protease is thus a prime therapeutic target, and great efforts have been devoted to the development of protease inhibitors, which have demonstrated efficacy in late phases of human clinical trials. Nevertheless, the high rate and error-prone nature of HCV replication have led to the emergence of resistance against the most promising protease inhibitors to date, such as boceprevir, telaprevir, and ITMN-191 (16, 17, 20, 30, 32, 36). Inhibitor potency often derives from molecular interactions that are not essential for substrate recognition and cleavage. Mutations in these regions of the protease can selectively prevent drug binding while still allowing for the recognition and cleavage of viral and host cell substrates. Thus, identification of the protease residues that are important for substrate binding is crucial and will ultimately facilitate the design of drugs that target these particular residues. A more detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying viral and host cell substrate recognition is therefore essential in facilitating a more rational approach to the design of more robust NS3/4A protease inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NMR chemical assignments were kindly provided by Herbert Klei of Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank David Smith of the LS-CAT beamline at Argonne National Laboratory for data collection for the apoenzyme; we also thank Shivender Shandilya and Vukica Šrajer for data collection for the TRIF complex at BioCARS, Madhavi Nalam and Rajintha Bandaranayake for assistance with structural refinement, and Aysegul Ozen, Seema Mittal, and Madhavi Kolli for their computational support.

Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the BioCARS Sector 14 was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, under grant RR007707. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor for the support of this research program (grant 085P1000817). National Institutes of Health grants R01-AI085051 and 2R01-GM4347 supported this work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexopoulou L., Holt A. C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R. A. 2001. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413:732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartenschlager R., Ahlborn-Laake L., Mous J., Jacobsen H. 1994. Kinetic and structural analyses of hepatitis C virus polyprotein processing. J. Virol. 68:5045–5055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bode W., Huber R. 1978. Crystal structure analysis and refinement of two variants of trigonal trypsinogen: trigonal trypsin and PEG (polyethylene glycol) trypsinogen and their comparison with orthorhombic trypsin and trigonal trypsinogen. FEBS Lett. 90:265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brunger A. T. 1992. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature 355:472–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter P., Wells J. A. 1988. Dissecting the catalytic triad of a serine protease. Nature 332:564–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 50:760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davis I. W., et al. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delaglio F., et al. 1995. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6:277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeLano W. L. 2008. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 10. Emsley P., Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferreon J. C., Ferreon A. C., Li K., Lemon S. M. 2005. Molecular determinants of TRIF proteolysis mediated by the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. J. Biol. Chem. 280:20483–20492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foy E., et al. 2005. Control of antiviral defenses through hepatitis C virus disruption of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:2986–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foy E., et al. 2003. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science 300:1145–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gallinari P., et al. 1998. Multiple enzymatic activities associated with recombinant NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 72:6758–6769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goddard T. D., Kneller D. G. SPARKY 3. University of California, San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 16. He Y., et al. 2008. Relative replication capacity and selective advantage profiles of protease inhibitor-resistant hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protease mutants in the HCV genotype 1b replicon system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1101–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kieffer T. L., et al. 2007. Telaprevir and pegylated interferon-alpha-2a inhibit wild-type and resistant genotype 1 hepatitis C virus replication in patients. Hepatology 46:631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krishnan R., Sadler J. E., Tulinsky A. 2000. Structure of the Ser195Ala mutant of human alpha-thrombin complexed with fibrinopeptide A(7-16): evidence for residual catalytic activity. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56:406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krissinel E., Henrick K. 2007. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372:774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lenz O., et al. 2010. In vitro resistance profile of the hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor TMC435. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1878–1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li K., et al. 2005. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:2992–2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin C., Pragai B. M., Grakoui A., Xu J., Rice C. M. 1994. Hepatitis C virus NS3 serine proteinase: trans-cleavage requirements and processing kinetics. J. Virol. 68:8147–8157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Major M. E., Feinstone S. M. 1997. The molecular virology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 25:1527–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCoy A. J., et al. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40:658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morris R. J., Perrakis A., Lamzin V. S. 2002. ARP/wARP's model-building algorithms. I. The main chain. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58:968–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nalam M. N., et al. 2010. Evaluating the substrate-envelope hypothesis: structural analysis of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors designed to be robust against drug resistance. J. Virol. 84:5368–5378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prabu-Jeyabalan M., Nalivaika E. A., Romano K., Schiffer C. A. 2006. Mechanism of substrate recognition by drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease variants revealed by a novel structural intermediate. J. Virol. 80:3607–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Romano K. P., Ali A., Royer W. E., Schiffer C. A. 2010. Drug resistance against HCV NS3/4A inhibitors is defined by the balance of substrate recognition versus inhibitor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sarrazin C., et al. 2007. SCH 503034, a novel hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor, plus pegylated interferon alpha-2b for genotype 1 nonresponders. Gastroenterology 132:1270–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steinkuhler C., et al. 1998. Product inhibition of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Biochemistry 37:8899–8905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tong X., et al. 2008. Characterization of resistance mutations against HCV ketoamide protease inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 77:177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. WHO 8 February 2010, posting date Vaccine research: hepatitis C. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis

- 34. Wittekind M., Weinheirner S., Zhang Y., Goldfarb V. August 2002. Modified forms of hepatitis C NS3 protease for facilitating inhibitor screening and structural studies of protease:inhibitor complexes. U.S. patent 6,333,186

- 35. Yao N., Reichert P., Taremi S. S., Prosise W. W., Weber P. C. 1999. Molecular views of viral polyprotein processing revealed by the crystal structure of the hepatitis C virus bifunctional protease-helicase. Structure 7:1353–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yi M., Ma Y., Yates J., Lemon S. M. 2009. Trans-complementation of an NS2 defect in a late step in hepatitis C virus (HCV) particle assembly and maturation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoneyama M., et al. 2005. Shared and unique functions of the DExD/H-box helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in antiviral innate immunity. J. Immunol. 175:2851–2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]