Abstract

An in vitro system that recapitulates the in vivo effect of AU-rich elements (AREs) on mRNA deadenylation has been developed from Xenopus activated egg extracts. ARE-mediated deadenylation is uncoupled from mRNA body decay, and the rate of deadenylation increases with the number of tandem AUUUAs. A novel ARE-binding protein called ePAB (for embryonic poly(A)-binding protein) has been purified from this extract by ARE affinity selection. ePAB exhibits 72% identity to mammalian and Xenopus PABP1 and is the predominant poly(A)-binding protein expressed in the stage VI oocyte and during Xenopus early development. Immunodepletion of ePAB increases the rate of both ARE-mediated and default deadenylation in vitro. In contrast, addition of even a small excess of ePAB inhibits deadenylation, demonstrating that the ePAB concentration is critical for determining the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation. These data argue that ePAB is the poly(A)-binding protein responsible for stabilization of poly(A) tails and is thus a potential regulator of mRNA deadenylation and translation during early development.

Keywords: In vitro deadenylation, AU-rich elements, development, mRNA stability, poly(A) tail

During early development, transcription is limited, and embryogenesis relies primarily on translational control mechanisms to regulate protein expression from a maternal store of mRNAs. One way translation levels are modulated is through regulated changes in mRNA poly(A) tail length. In general, polyadenylation of an mRNA leads to its translational up-regulation, whereas deadenylation reduces translation (Standart and Jackson 1990; Richter 1999). Changes in poly(A) tail length have little effect on the stability of the mRNA body until the mid-blastula transition (MBT) (Audic et al. 1997; Voeltz and Steitz 1998). Thus, the pre-MBT embryo is useful for studying the role of cis-acting elements on mRNA adenylation and deadenylation and the resulting effects of poly(A) tail length on mRNA translatability.

In the cytoplasm of vertebrate cells, the poly(A) tails of mRNAs are bound by the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP1), a highly conserved ∼70-kD protein that stabilizes the poly(A) tail by protecting it from deadenylases and 3′–5′ exonucleases (Bernstein et al. 1989; Ross 1995). The N terminus of PABP1 consists of four RNA binding domains (RBDs I–IV). Most evidence suggests that RBDs I and II are the domains that bind the poly(A) tail, although all four RBDs have high affinity for RNA (Kuhn and Pieler 1996; Deardoff and Sachs 1997). PABP bound to the poly(A) tail interacts (via RBD II) with the translation factor eIF4G, which bridges to the cap-binding protein eIF4E at the 5′ end of the mRNA (Christensen et al. 1987; Tarun and Sachs 1996; Imataka et al. 1998; Kessler and Sachs 1998; Wells et al. 1998; Otero et al. 1999). The resulting circularization of the mRNA molecule stimulates assembly of the translation initiation complex at the 5′ cap, thereby increasing the rate of translation (Gallie and Tanguay 1994; Preiss and Hentze 1998).

Sequence elements within the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of an mRNA can promote adenylation or deadenylation. Most mRNAs contain a poly(A) addition signal (consensus AAUAAA), which directs 3′ end formation and polyadenylation of the newly transcribed mRNA in the nucleus (Wickens et al., 2000). Some mRNAs also contain a cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE, consensus sequence of UUUUA1–2U) within their 3′-UTR that acts in conjunction with AAUAAA to promote poly(A) tail lengthening and translational activation in maturing oocytes and early embryos (Richter 2000; Wickens et al. 2000). In Xenopus, egg maturation coincides with the breakdown of the nuclear membrane and the redistribution of at least one deadenylase, the default deadenylase (DAN, also called PARN) (Korner et al. 1998). mRNAs that do not contain a CPE are substrates for default deadenylation coincident with translational inactivation of these mRNAs (Fox and Wickens 1990; Varnum and Wormington 1990).

Messages can also contain 3′-UTR elements that signal deadenylation. During early Xenopus development, several sequences act in a stage-specific manner. For example, members of the Eg mRNA family (including Eg1-cdk2, Eg2, Eg5, and c-mos) contain a CPE that enhances polyadenylation in the mature egg, but also contain the Eg-specific deadenylation element (EDEN) which promotes deadenylation following egg fertilization (Bouvet et al. 1994; Sheets et al. 1994). The highly conserved AU-rich element (ARE) found in the 3′-UTR of Xenopus c-myc also directs deadenylation of a chimeric mRNA following egg fertilization (Voeltz and Steitz 1998). The ARE of human GMCSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor), which contains seven AUUUA sequences, directs slow deadenylation of a chimeric mRNA in the Xenopus stage VI oocyte and rapid ARE-directed deadenylation of the mRNA following egg fertilization (Voeltz and Steitz 1998).

During Xenopus early development, the body of the mRNA following ARE-dependent deadenylation remains stable until the mid-blastula transition (MBT) (Voeltz and Steitz 1998). In contrast, in mammalian tissue culture cells, ARE-dependent deadenylation results in rapid degradation of the mRNA body (Wilson and Treisman 1988; Shyu et al. 1991; Chen and Shyu 1994). Whereas many ARE-binding proteins have been identified (Brennan and Steitz 2001), only two have been shown in vivo to influence the stability of an ARE-containing transcript: HuR appears to be stabilizing (Fan and Steitz 1998; Levy et al. 1998; Peng et al. 1998; Ford et al. 1999) whereas hnRNP D appears destabilizing (Loflin et al. 1998), but neither protein has a measurable effect on the rate of ARE-dependent deadenylation in vitro or in vivo.

Our goal here was to identify factors involved in ARE-dependent deadenylation during Xenopus early development. We have developed an in vitro system from Xenopus activated egg extracts that recapitulates ARE-mediated deadenylation in vivo (Voeltz and Steitz 1998). Since ARE-mediated deadenylation is uncoupled from mRNA body decay, the effects of overexpression or depletion of factors on deadenylation alone can be assessed. These analyses have surprisingly uncovered the existence of a novel PABP, ePAB (for embyonic PABP), that also specifically binds AREs. Its expression and properties argue that ePAB is the primary PABP that regulates poly(A) tail length and hence the translatability of mRNAs (with or without an ARE) during Xenopus early development.

Results

An in vitro system for AUUUA-mediated deadenylation

Xenopus egg extracts have been useful in studying both default and EDEN-specific deadenylation in vitro (Legagneux et al. 1995; Dehlin et al. 2000). Therefore, we tested whether mature/activated egg extracts could also be used to study ARE-mediated deadenylation. Mature eggs were activated with calcium ionophore, and high-speed supernatant extracts (HSS) were prepared and optimized as described previously (Leno and Laskey 1991). The reporter transcripts used (Fig. 1) contained the 62-nucleotide ARE from human GMCSF, which was previously shown to direct rapid in vivo deadenylation following Xenopus egg fertilization or activation (Voeltz and Steitz 1998).

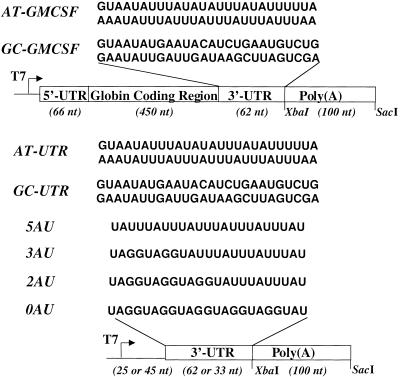

Figure 1.

Substrates used for in vitro and in vivo deadenylation. Full-length chimeric mRNAs AT-GMCSF and GC-GMCSF contain the Xenopus globin 5′-UTR (66 nt), human β-globin coding region (450 nt), the indicated 3′-UTR (62 nt), and a poly(A) tail of 100 nt. Poly(A)− transcripts AT-UTR and GC-UTR contain a short leader sequence (25 nt) followed by the UTR sequence (62 nt). Poly(A)+ transcripts AT-UTR, GC-UTR, 0AU, 2AU, 3AU, and 5AU contain a short leader sequence (45 nt), followed by the UTR sequence (62 or 35 nt) and a poly(A) tail of 100 nt.

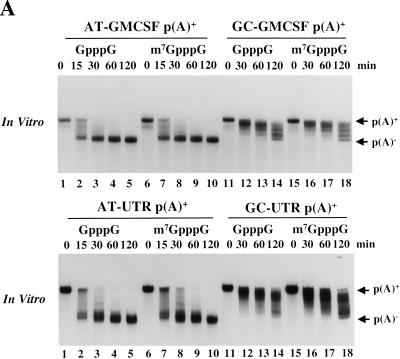

Figure 2A (top panel) shows that an mRNA substrate containing the wild-type ARE (AT-GMCSF) is rapidly deadenylated in vitro relative to substrate containing the mutated ARE (GC-GMCSF), faithfully reproducing the in vivo activities of these 3′-UTRs (Voeltz and Steitz 1998). To determine whether the ARE can also direct deadenylation of a short RNA that does not contain a coding region, we examined the poly(A)+ AT-UTR and GC-UTR substrates (Fig. 1). The rate of deadenylation of the noncoding AT-UTR p(A)+ (Fig. 2A, bottom panel) was similar to that of the longer AT-GMCSF p(A)+ transcript (Fig. 2A, top panel) in vitro (t1/2 ∼ 15 min), suggesting that neither length nor translation are requirements for active deadenylation. The mutant ARE transcripts GC-GMCSF p(A)+ and GC-UTR p(A)+ (Fig. 2A, lanes 11–18) had much lower rates of deadenylation (t1/2 ∼ 2 h) and produced a laddered pattern of products. We believe that this activity is due to the presence of the default deadenylase DAN (Korner et al. 1998) in the extract.

Figure 2.

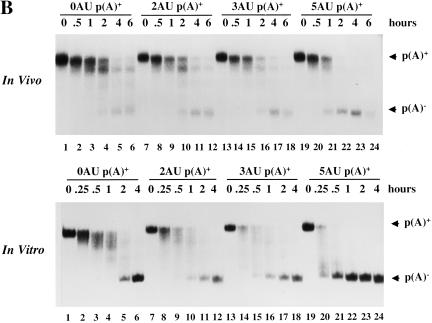

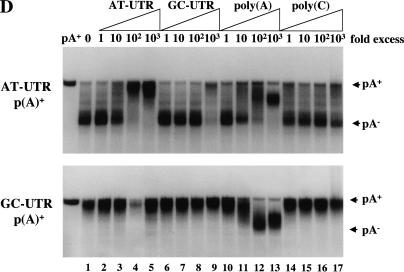

In vitro deadenylation assay. (A) The indicated [α-32P]UTP labeled and polyadenylated substrates (see Fig. 1) containing either a GpppG (lanes 1–5,11–14) or m7GpppG cap (lanes 5–10,15–18) were incubated at 22°C in activated egg extract. Aliquots were removed for analysis at the times indicated and fractionated by 6% PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. (B) [α-32P]UTP-labeled, m7GpppG capped, and polyadenylated transcripts containing different numbers of tandem AUUUA repeats (see Fig. 1) were cytoplasmically injected into mature/activated eggs (top panel) or incubated in the in vitro system (bottom panel). RNA was isolated at the times indicated. (C) Data from B were quantitated by PhosphorImager and plotted as the % poly(A)− (calculated as the cpm in the p(A)− position divided by the total cpm between the p(A)+ and p(A)− markers) as a function of time. (D) Fifty fmoles [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ (top panel) or GC-UTR p(A)+ (bottom panel) were incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled competitor RNAs for 30 min in the in vitro system. Unlabeled competitor AT-UTR or GC-UTR was added at 1× (50 fmoles), 10× (500 fmoles), 102× (5 pmoles), and 103× (50 pmoles) relative to substrate, while homopolymeric poly(A) or poly(C) (Sigma) was added at 1× (2.5 ng), 10× (25 ng), 102× (250 ng), and 103× (2.5 μg).

Because methylation of the 5′ cap structure alters deadenylation and decay rates in HeLa cell systems (Dehlin et al. 2000; Gao et al. 2000), we assessed its effect on deadenylation in our extract. Figure 2A (top and bottom panels) shows that AT-GMCSF p(A)+ and AT-UTR p(A)+ substrates are deadenylated at equivalent rates when capped with either GpppG or m7GpppG. Cap methylation also does not affect the rate of default deadenylation of the GC mutant substrates, although we have not tested whether the GpppG capped substrates become methylated during incubation in the extract.

In mammalian cells, the number of tandem AUUUAs present in the 3′-UTR correlates with in vivo rates of mRNA deadenylation and decay (Lagnado et al. 1994; Zubiaga et al. 1995). To determine whether the deadenylation rate in Xenopus eggs and egg extract responds similarly, we constructed substrates with 0, 2, 3, and 5 tandem copies of the AUUUA sequence (0AU, 2AU, 3AU, and 5AU, Fig. 1). Each polyadenylated RNA was first microinjected into mature activated eggs, revealing that the number of AUUUAs indeed correlates with deadenylation rates in vivo: 5 AUUUA > 3AUUUA > 2AUUUA > 0AUUUA. (Fig. 2B,C, top panel). The same relative rates were then observed in the in vitro system (Fig. 2B,C, bottom panel). A minimum of two tandem AUUUA copies is required to obtain a rate greater than that of default deadenylation (data not shown). We conclude that the egg extract in vitro system faithfully reproduces in vivo effects of the ARE on mRNA deadenylation.

Identification of trans-acting factors

To begin to characterize trans-acting factors directing ARE-mediated deadenylation, we assessed their RNA-binding properties in competition experiments. Radiolabeled AT-UTR p(A)+ or GC-UTR p(A)+ substrates (see Fig. 1) were incubated for 30 min in egg extract in the presence of increasing concentrations of the following unlabeled RNAs: AT-UTR, GC-UTR, poly(A), or poly(C) (Fig. 2D). AT-UTR (lanes 2–5) proved to be a potent competitor of ARE-mediated deadenylation, detectably reducing deadenylation at only 10-fold excess over substrate; GC-UTR (lanes 6–9) began to compete only at 1000-fold excess. Poly(A) addition (lanes 10–13) efficiently competed ARE-mediated deadenylation at 10–100-fold excess, whereas no competition was observed for poly(C), even at a 1000-fold excess (lanes 14–17). In contrast to results obtained for the AT-UTR p(A)+ substrate, addition of a 10–100-fold excess of poly(A) activated deadenylation of the GC-UTR p(A)+ substrate (lanes 10–13), presumably by displacing the protective PABP from the poly(A) tail (Bernstein et al. 1989). Further poly(A) addition then began to inhibit deadenylation of the GC-UTR p(A)+ substrate at very high concentrations (>1000-fold excess). These data suggest an ARE-dependent stabilization of the poly(A) tail in the presence of poly(A) competitor. The addition of 1000-fold excess of poly(A) reproducibly resulted in the accumulation of partially deadenylated products for both transcripts (Fig. 2D, lanes 12 and 13), perhaps because of competition for the deadenylase.

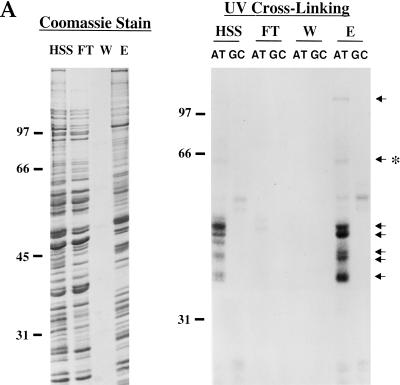

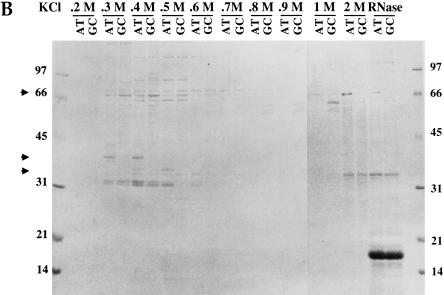

Initially we attempted to purify factors involved in ARE-dependent deadenylation by column chromatography, but no activity was recovered following fractionation by cation or anion exchange columns, heparin sepharose, RNA affinity columns, sucrose gradients, or by ammonium sulfate precipitation. Nor did recombination of separated fractions restore activity. Thus, we pursued factors that selectively bind an ARE sequence, AT-UTR (see Fig. 1), after enriching RNA-binding proteins present in the active egg extract by passage over heparin sepharose. The HSS extract was loaded onto heparin sepharose at moderate salt (100 mM KCl) in assay buffer, extensively washed, and eluted with a salt gradient in assay buffer. The Coomassie stained gel (Fig. 3A, left panel) of the 1 M KCl fraction revealed enrichment for certain bands, confirmed to be RNA binding proteins by UV crosslinking to [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR and GC-UTR RNAs. Note that both the retention of ARE-specific RNA binding proteins (indicated by arrows in Fig. 3A, right panel) by the heparin column and their elution at 1 M KCl (Fig. 3A, right panel, cf. lanes HSS and E) were essentially quantitative.

Figure 3.

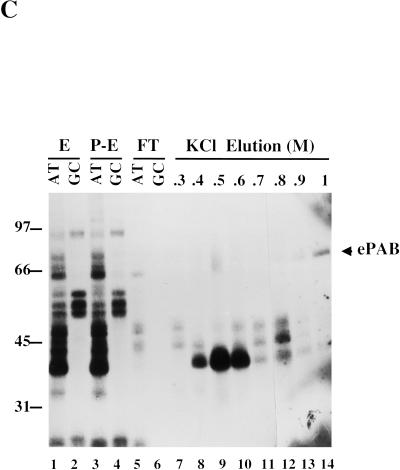

Purification of the ARE-binding protein ePAB. (A) The activated egg extract (HSS) was loaded onto heparin sepharose, washed (W, final wash) and eluted with 1 M KCl (E). Equivalent fractions of these samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie (left panel). Comparable fractions were also crosslinked to [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR or GC-UTR transcripts (right panel). Arrows denote ARE-specific crosslinked bands, one of which (*) is ePAB. (B) Colloidal blue (Sigma) staining of a 15% SDS gel analysis of the KCl elution profile from the AT-UTR (AT) and GC-UTR (GC) AADA columns. The molarity at the start of the elution of each fraction is indicated at the top. RNase A was used to elute proteins remaining bound to the columns following the 2M KCl elution. Arrows indicate the three proteins bound specifically to the AT-UTR column. (C) Fractions from the heparin sepharose column (E is the 1M elution, P-E is the same sample after pre-clearing on AADA beads) and the ATUTR AADA column (FT is the flow through at 0.1 M KCl, and KCl elution fractions are from 0.3 to 1M) were UV-crosslinked to a [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR (AT) (lanes 1,3,5,7–14) or GC-UTR (GC) (lanes 2,4,6) probe. Purified ePAB in lane 14 is indicated by an arrow.

The AT-UTR sequence (see Fig. 1) was chosen as an affinity reagent to purify ARE-binding proteins since it is sufficient to promote rapid deadenylation both in vivo (Voeltz and Steitz 1998) and in vitro (Fig. 2A) and can also compete for ARE-specific deadenylation in vitro (Fig. 2D). The eluate from the heparin column (Fig. 3A, lane E) was dialyzed back into assay buffer and then pre-incubated with adipic acid dihydrazide agarose (AADA) beads to reduce nonspecific binding to the RNA affinity column. The pre-cleared fraction was bound in batch to AT-UTR covalently coupled at its 3′ end to AADA beads in the presence of 0.5 mg/mL heparin as a nonspecific competitor. A GC-UTR RNA affinity column was run in parallel to identify which RNA binding proteins are specific for the ARE. Colloidal blue staining of an SDS gel of fractions eluted by a linear KCl gradient from both the AT-UTR and GC-UTR columns revealed three proteins (∼ 40 kD at 0.3–0.4 M, 36 kD at 0.4–0.5 M, and 65 kD at 1–2 M) specifically retained by AT-UTR (Fig. 3B, cf. lanes AT and GC). Crosslinking of the fractions eluted from the AT-UTR column to UTP-labeled AT-UTR demonstrated that these proteins can also crosslink to the ARE (Fig. 3C).

Two of the isolated proteins were identified as known ARE-binding proteins: the ∼40-kD protein crossreacts with anti-hnRNP D antibody (Dempsey et al. 1998), and the ∼36-kD protein was identified as ElrA, the Xenopus homolog of HuR (Good 1995), by both Western blot analysis and MALDI-MS (data not shown). The third ∼65-kD protein could not be identified by MALDI-MS and did not react with anti-PABP1 antibody (Gorlach et al. 1994).

ePAB, a new PABP

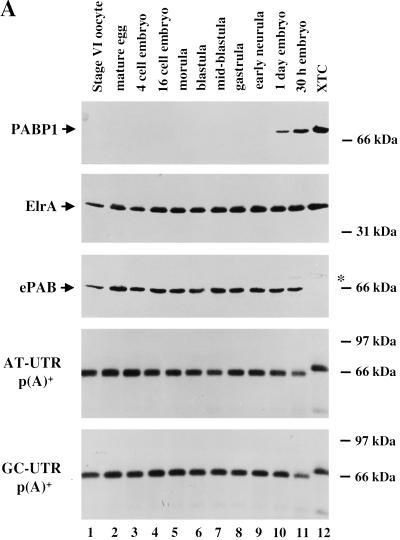

To identify the ∼65-kD protein present in the 1–2 M eluate from the AT-UTR column, the band was excised from the gel (Fig. 3B) and subjected to trypsin digestion, with subsequent microsequencing of three tryptic peptides (performed by the W.M. Keck Facility at Yale). Degenerate primers (5′-Deg and 3′-Deg) corresponding to two of these tryptic peptides were used to amplify by PCR the intervening cDNA sequence from a λ II Xenopus ovary cDNA library (Cote et al. 1999). The complete cDNA sequence was then obtained by PCR amplification of the λ II ovary cDNA library using gene-specific and vector-specific primer pairs.

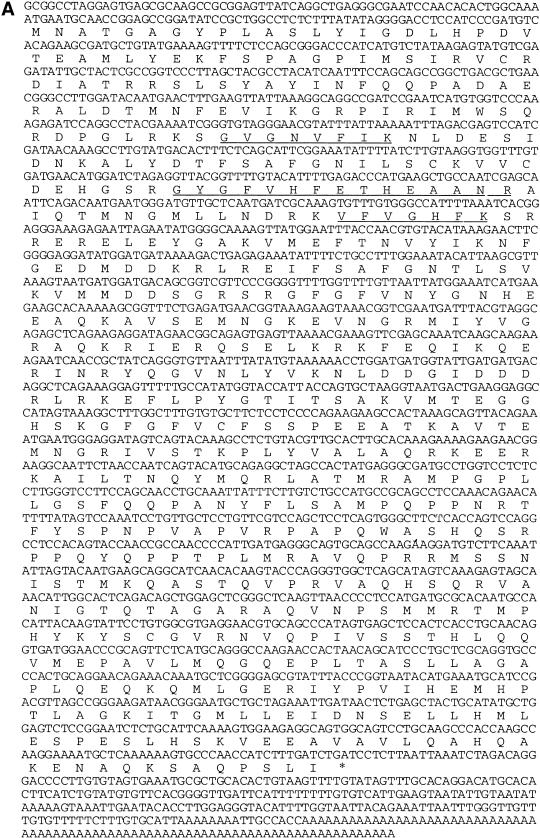

The cDNA encodes a novel isoform of the poly(A) binding protein, which we have named ePAB for embryonic PABP. The complete cDNA and predicted amino acid sequence of Xenopus ePAB are shown in Figure 4A, with the peptides identified by microsequencing underlined. The open reading frame encodes a 629 amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 70.6 kD. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of ePAB, Xenopus PABP1, human PABP1, and human inducible PABP (iPABP) (Fig. 4B) reveals that ePAB has 72% identity to human and Xenopus PABP1 and 67% identity to iPABP. The N-terminal regions, including RBDs I–IV, are 82% conserved between ePAB and Xenopus PABP1, whereas the C-terminal regions are only 56% identical (Xenopus and human PABP1 are 95% identical in both regions).

Figure 4.

DNA and predicted amino acid sequences of the Xenopus ePAB gene. (A) Underlined are amino acids identified by microsequence analysis of tryptic peptides. The 5′ untranslated region may not be complete, but there are two upstream UGAs in frame with the initiating methionine, arguing that the coding region is complete. In the 3′ untranslated region, a putative polyadenylation signal (minor class, AUUAAA) is located 12 nucleotides upstream of the poly(A) tail. (B) Amino acid sequences of Xenopus ePAB (629 aa), Xenopus (Xl) PABP1 (633 aa, accession no. P20965) (Zelus et al. 1989), human (Hs) PABP1 (636 aa, accession no. P11940) (Grange et al. 1987), and human (Hs) iPABP (644 aa) (accession no. NM003819) (Yang et al. 1995) are compared. Shaded regions denote identity. RBDs I, II, III and IV extend from human PABP1 positions 6 to 90, 92 to 176, 191 to 269, and 288 to 372, respectively (Burd et al. 1991).

ePAB is the major poly(A)-binding protein expressed during Xenopus early development

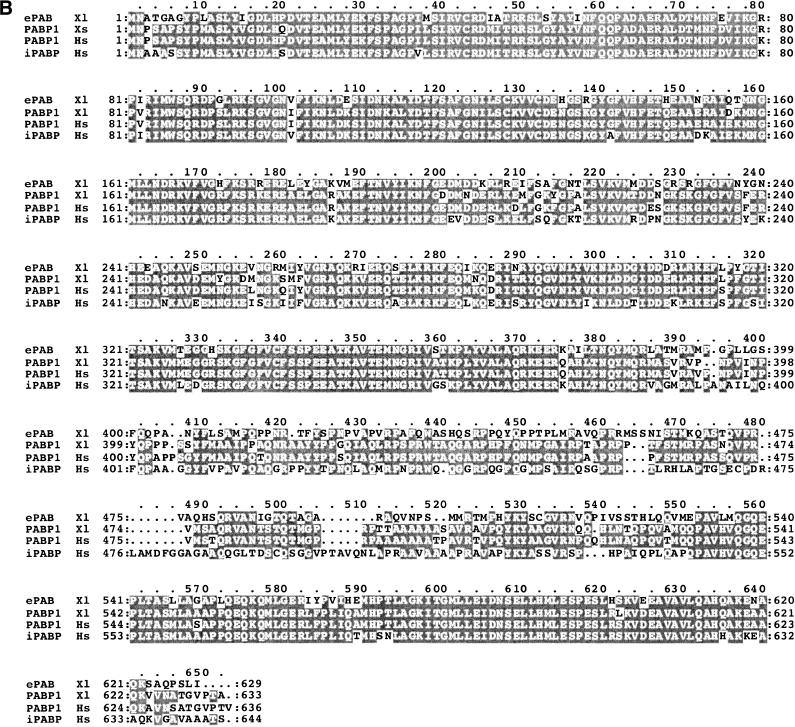

To analyze the expression of ePAB protein, polyclonal antibodies were produced in rabbits using the divergent C-terminal 243 amino acids of ePAB as immunogen. Blots of gel-fractionated proteins from various stages of Xenopus early development were immunostained and compared to kidney-derived Xenopus tissue culture (XTC) extract (Fig. 5A). Monoclonal antibody to HuR identified ElrA, which is expressed at constant levels throughout development (Wu et al. 1997) and served as a loading control. The level of ePAB remains constant throughout early development (stage VI oocyte through the 30-h embryo) but is not detectable in XTC cells. In contrast, as previously reported (Zelus et al. 1989), PABP1 is not detected by immunostaining with monoclonal antibody (Gorlach et al. 1994) until 24 h following fertilization, but is present at moderate levels in XTC cells. The anti-PABP1 antibody did not crossreact with ePAB, while the anti-ePAB antibody did crossreact weakly with PABP1 (data not shown). We conclude that ePAB is the major PABP expressed in the stage VI oocyte through the neurula stage of Xenopus early development.

Figure 5.

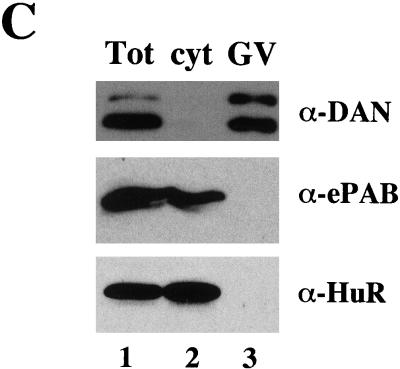

ePAB expression during Xenopus early development. (A) Extract from various stages of development [1/2-egg equivalent per lane: stage VI oocyte, mature egg, 4-cell embryo (1.5 h), 16-cell embryo (2.5 h), morula (3.5 h), blastula (5 h), mid-blastula (7 h), gastrula (9 h), early neurula (12 h), 1-day embryo, and 30-h embryo] and XTC cells were fractionated by 15% PAGE and immunostained with anti-ePAB (third panel), monoclonal anti-PABP1 (top panel), or monoclonal anti-HuR, identifying ElrA (second panel), antibodies. The blot that was initially probed with anti-PABP1 was later reprobed for ePAB; the asterisk (*) marks the remaining signal from anti-PABP1, therefore indicating the mobility of PABP1 relative to ePAB. The same samples were also UV-crosslinked to [α-32P]ATP labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ (fourth panel) and GC-UTR p(A)+ (bottom panel). (B) Egg extract was crosslinked to: [α-32P]ATP-labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ (lane 1), [α-32P]ATP-labeled GC-UTR p(A)+ (lane 4), or [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR (lane 7). Crosslinked samples (Total) were immunoprecipitated with anti-ePAB (α-ePAB, lanes 3,6,9) or preimmune (α-Pre, lanes 2,5, or 8) serum. The arrow denotes the ∼65-kD crosslinked band precipitated by anti-ePAB. (C) Stage VI oocytes were manually enucleated and 1/2-oocyte equivalents of the total (Tot), cytoplasmic (cyt), and nuclear (GV) fractions were immunostained with anti-ePAB, monoclonal anti-PABP1, and monoclonal anti-HuR, identifying ElrA, antibodies.

Crosslinking experiments confirmed that ePAB is the sole poly(A)-binding protein detectable during Xenopus early development. The same extracts as examined above were UV-crosslinked to either AT-UTR p(A)+ or GC-UTR p(A)+ (Fig. 5A, bottom panels) labeled with [α-32P]ATP so that proteins binding to the poly(A) tail would be detected (Fig. 5A). The major crosslinked band for both substrates was a ∼65-kD protein, present throughout development. A larger ∼70-kD crosslinked band present only in XTC extract corresponds to the mobility of PABP1.

The identification of the ∼65-kD ([α-32P]ATP-labeled) crosslinked band in the egg extract as ePAB was established by immunoprecipitation. Following crosslinking and treatment with RNases A and One, anti-ePAB antibodies efficiently precipitated a labeled 65-kD band, whereas the preimmune serum did not (Fig. 5B, cf. lane 3 with lane 2 and lane 6 with lane 5). Even when crosslinked to [α-32P]UTP-labeled substrate (AT-UTR), ePAB could be selected from the much more complicated profile of RNA binding proteins by our anti-ePAB antibody (lanes 7 and 9). We conclude that ePAB not only is the major poly(A) binding protein during early development but interacts with AREs in our egg extract active in ARE-mediated deadenylation.

Mammalian PABP1 is localized to the cytoplasm (Gorlach et al. 1994) whereas PABP2, a 32-kD protein that functions in nuclear polyadenylation, is present predominantly in the nucleus (Wahle 1991). To determine the cellular localization of ePAB, stage VI oocytes were manually enucleated, and cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were subjected to Western analysis using anti-ePAB antibodies. Figure 5C shows that the cytoplasmic compartment contains all the detectable ePAB protein. The blots were also immunostained for the cytoplasmic ElrA protein (bottom panel) (Wu et al. 1997) and the nuclear DAN (top panel) (Korner et al. 1998), establishing both successful fractionation and loading.

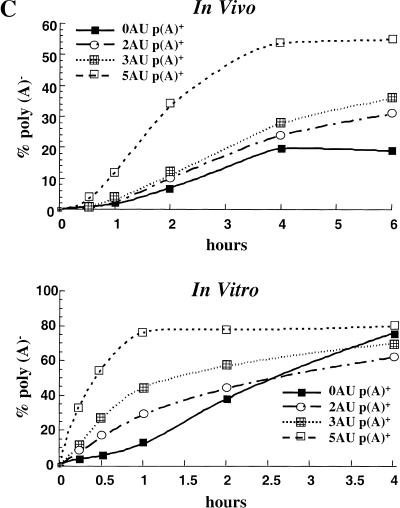

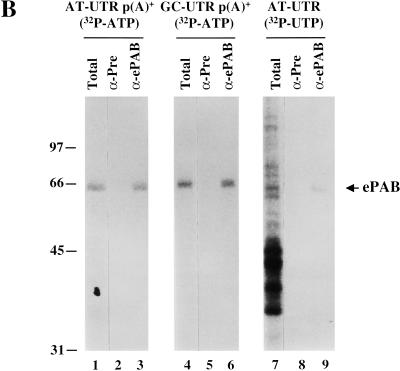

ePAB protects the poly(A) tail of mRNAs with or without an ARE

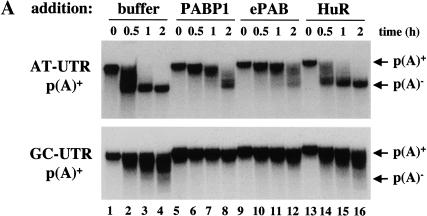

Overexpression of PABP1 in Xenopus mature eggs has been reported to slow the rate of default deadenylation, demonstrating that PABP1 can function to protect poly(A) tails from deadenylation (Wormington et al. 1996). To determine whether ePAB similarly regulates ARE-mediated deadenylation, we added recombinant 6xHis-tagged ePAB to the HSS extract and assessed the rate of deadenylation of AT-UTR p(A)+ and GC-UTR p(A)+ substrates. Addition of recombinant ePAB (equivalent to the level of endogenous ePAB) inhibited the deadenylation of both substrates (Fig. 6A, lanes 9–12) relative to extract that received no recombinant protein (Fig. 6A, lanes 1–4) or was supplemented with an equivalent amount of recombinant 6xHis HuR, another RBD-containing RNA binding protein (Fig. 6A, lanes 13–16). Inhibition by ePAB was similar to that seen by the addition of equivalent concentrations of 6xHis-tagged Xenopus PABP1 (Fig. 6A, lanes 5–8). Interestingly, even a small excess of ePAB protein (twice the level of endogenous) dramatically decreased the deadenylation of substrates with or without an ARE.

Figure 6.

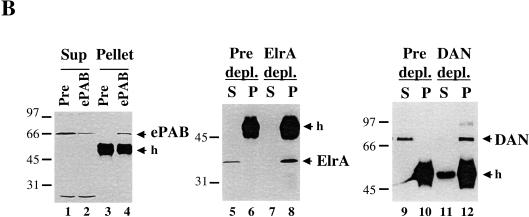

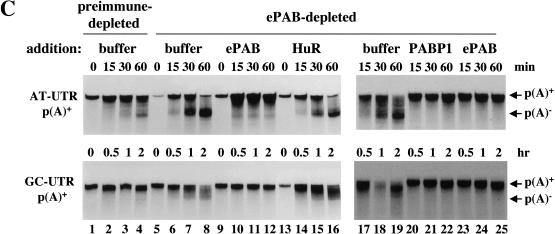

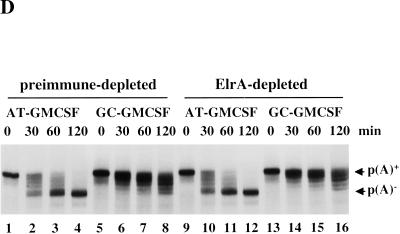

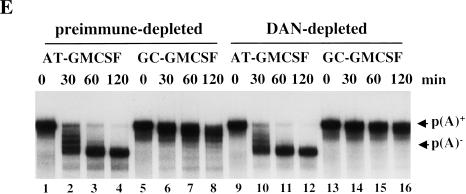

Effect of trans-acting factors on in vitro deadenylation. (A) [α-32P]UTP labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ (top panel) or GC-UTR p(A)+ (bottom panel) was incubated under in vitro assay conditions with the addition of buffer alone (lanes 1–4), or equivalent concentrations (∼10 ng/μL HSS) of recombinant 6xHis PABP1 (lanes 5–8), 6xHis ePAB (lanes 9–12), or 6xHis HuR (lanes 13–16), and aliquots were removed for analysis at the times indicated. (B) Western blot analyses of egg extracts immunodepleted (depl.) for ePAB (lanes 1–4), ElrA (lanes 5–8), or DAN (lanes 9–12). The bands corresponding to these as well as molecular weight marker proteins and the heavy chain of immunoglobulin (h) are indicated. In each case, the supernatant (Sup or S) and pellet (Pellet or P) fractions were analyzed, with the corresponding preimmune serum (Pre) used in parallel. (C) [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ (top panel) or GC-UTR p(A)+ (bottom panel) substrate was incubated in preimmune-depleted (lanes 1–4) or α-ePAB-depleted (lanes 5–25) extract supplemented with: buffer alone (lanes 5–8,17–19), or equivalent concentrations (∼10 ng/μL HSS) of recombinant 6xHis ePAB (lanes 9–12,23–25), 6xHis HuR (lanes 13–16), or 6xHis PABP1 (lanes 20–22). Aliquots were withdrawn for RNA analysis at the times indicated. (D) [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-GMCSF p(A)+ or GC-GMCSF p(A)+ substrate was incubated in either ElrA-depleted (lanes 9–16) or preimmune-depleted extract (lanes 1–8) under deadenylation assay conditions and aliquots withdrawn for RNA analysis at the times indicated. (E) [α-32P]UTP-labeled AT-GMCSF p(A)+ or GC-GMCSF p(A)+ substrate was incubated in either DAN-depleted extract (lanes 9–16) or preimmune-depleted extract (lanes 1–8) under deadenylation assay conditions for the times indicated and analyzed as above.

In a converse experiment, we immunodepleted more than 80% of ePAB from HSS extract using anti-ePAB antibodies. The deadenylation activity of the ePAB-depleted extract (Fig. 6B, lane 2) relative to the preimmune-depleted HSS extract (Fig. 6B, lane 1) was assayed by incubation with either AT-UTR p(A)+ or GC-UTR p(A)+ (Fig. 6C). Lanes 5–8 compared to 1–4 show that both substrates were deadenylated at a more rapid rate after depletion of ePAB. Recombinant ePAB protein was then added to the ePAB-depleted extract to return the level to that of endogenous ePAB (∼10 ng recombinant 6xHis-tagged protein/μL HSS). Figure 6C, lanes 9–12, shows that the effects of ePAB depletion are reversed for both substrates. In contrast, adding an equivalent amount of recombinant 6xHis HuR to the ePAB-depleted extract did not inhibit deadenylation (lanes 13–16). These results demonstrate that ePAB functions in vitro to protect the poly(A) tail of substrates with or without an ARE.

To determine whether PABP1 could function similarly to inhibit deadenylation in an ePAB-depleted extract, the extract was supplemented with either buffer (Fig. 6C, lanes 17–19) or equivalent concentrations (∼10 ng recombinant 6xHis-tagged protein/μL HSS) of PABP1 (Fig. 6C, lanes 20–22) or ePAB (Fig. 6C, lanes 23–25). Indeed, PABP1 and ePAB similarly inhibit deadenylation in the ePAB-depleted extract.

Immunodepletion of ElrA and DAN do not affect ARE-mediated deadenylation

ElrA (the Xenopus homolog of HuR) was one of the proteins that bound specifically to the ARE-affinity column (Fig. 3). Overexpression of HuR in mammalian tissue culture cells leads to a 2–3-fold stabilization of ARE-containing transcripts (Fan and Steitz 1998; Levy et al. 1998; Peng et al. 1998). To test whether ElrA functions to stabilize an ARE-containing transcript by affecting its rate of deadenylation, we asked whether immunodepletion of ElrA from the in vitro system affects ARE-mediated deadenylation. Using anti-HuR polyclonal antibody, > 95% of ElrA was immunodepleted from the extract (Fig. 6B, lanes 7 and 8). The level of ARE-mediated deadenylation of the AT-GMCSF p(A)+ substrate was measured and compared to extract depleted with preimmune antibody (lanes 5 and 6). Figure 6D shows no quantitative effect on either ARE-mediated deadenylation (cf. lanes 9–12 with lanes 1–4) or default deadenylation (cf. lanes 13–16 with lanes 5–8).

The deadenylase DAN is responsible for the default deadenylation of mRNAs that do not contain a CPE in the mature egg (Korner et al. 1998). It is possible that DAN also functions in ARE-mediated deadenylation, perhaps by becoming more processive in the presence of factors specifically recruited to an ARE-containing transcript. Polyclonal antibody to DAN (Korner et al. 1998) was therefore used to immunodeplete DAN (greater than 95%) from the in vitro system (Fig. 6B, lane 11). Compared to the preimmune-depleted extract (Fig. 6B, lane 9), no difference in the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation was observed (Fig. 6E, cf. lanes 9–12 with lanes 1–4). However, depletion of DAN did result in a reduction in the rate of default deadenylation on the GC-GMCSF substrate in vitro (cf. lanes 13–16 with lanes 5–8), as expected (Korner et al. 1998).

Finally, an ∼40-kD protein that reacts with anti-hnRNPD antibody eluted at 0.3–0.4M KCl from the AT-UTR column (Fig. 3B). This polyclonal antibody (Dempsey et al. 1998) immunostains four bands in Xenopus egg extract that range from 35 to 45 kD (data not shown) and presumably correspond to the four isoforms of hnRNP D described in mammalian cells. Immunodepletion attempts yielded only 50–75% depletion, and did not reveal any role for hnRNP D in ARE-mediated deadenylation (data not shown).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that Xenopus activated egg extracts can be used to study ARE-mediated deadenylation uncoupled from decay in vitro. The number of tandem AUUUAs present within the substrate correlates with the rate of deadenylation in vitro, faithfully reproducing the effect of 3′-UTR sequences observed in injected mature/activated eggs (Fig. 2B,C). A similar correlation was previously observed between mRNA decay rate and the number of AUUUAs in mammalian tissue culture cells (Lagnado et al. 1994; Chen and Shyu 1995; Zubiaga et al. 1995). Our data are the first to establish a relationship between the number of AUUUAs and the rate of deadenylation, separate from an effect on decay.

We purified from this extract a novel cytoplasmic ARE and poly(A) binding protein, ePAB. Two lines of evidence argue that ePAB, rather than PABP1, is the major poly(A) binding protein functioning to protect poly(A) tails in the stage VI oocyte through early development. First, ePAB protein is expressed throughout early development, whereas PABP1 is not detectable (Fig. 5). Secondly, immunodepletion of ePAB from our in vitro system markedly increases the rate of deadenylation of poly(A)+ substrates in vitro (Fig. 6C). Deadenylation is extremely sensitive to the levels of ePAB, since even a two-fold increase in ePAB results in the inhibition of both ARE-mediated and default deadenylation in vitro (Fig. 6A). In contrast, depletion of the ARE-binding protein ElrA or the default deadenylase DAN does not noticeably affect the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation (Fig. 6D,E).

A novel embryonic poly(A) binding protein, ePAB

ePAB encodes a 629-amino-acid protein with 72% identity to Xenopus and human PABP1 (Fig. 4B) and contains four highly conserved RNA binding domains (RBDs) I–IV (Burd et al. 1991). Comparison of RBDs I and II from ePAB and PABP1 reveals that 19 of the 20 amino acids that make side chain contacts to poly(A) in the high-resolution crystal structure of PABP1 (Deo et al. 1999) are conserved in ePAB. However, even in the N-terminal region that includes RBDs I–IV, the proteins are only 82% identical, whereas this region is more highly conserved for PABP1 from different species (> 95% human to Xenopus). Divergence of the RNA binding domains may contribute to the specificity of ePAB for ARE-containing sequences, though both yeast Pab1p and Xenopus PABP1 have high affinity for poly(U) as well as poly(A) (Nietfeld et al. 1990; Burd et al. 1991). Likewise, differences between RBD II of PABP1 and ePAB may change its affinity for eIF4G (Kessler and Sachs 1998; Otero et al. 1999). The C-terminal region of ePAB is significantly more divergent, with only 56% identity to PABP1. Though ePAB is less similar to human iPABP than to PABP1, many of the amino acids in ePAB and iPABP that differ from PABP1 are changed to the same amino acid (see Fig. 4B). It remains to be determined whether there is a mammalian homolog of ePAB.

ePAB is the predominant poly(A)-binding protein during Xenopus early development

We have demonstrated by both Western blot analysis and UV-crosslinking to substrates with [α-32P]ATP-labeled poly(A) tails that ePAB is the predominant poly(A)-binding protein expressed during Xenopus early development (Fig. 5A). Previously, Xenopus PABP1 was shown to be undetectable prior to neurulation by Western blot analysis (Zelus et al. 1989). This led to the hypothesis that PABP1 was present at levels so low that the binding sites presented by egg mRNAs would not be filled. The total binding sites calculated for the Xenopus stage VI oocyte is 2–3 × 1011, assuming 4 PABP sites (of 25 nucleotides) per poly(A)+ tail (Sagata et al. 1980). We have estimated the concentration of ePAB in the stage VI oocyte by comparing a Western blot of a 1/2 oocyte equivalent to a titration of known quantities of recombinant ePAB protein (data not shown). The stage VI oocyte contains ∼50 ng or roughly 5 × 1011 molecules of ePAB (calculated molecular weight, 70.6 kD), arguing that there are 1–2 times as many molecules of ePAB in the oocyte as there are binding sites on the poly(A) tails of total oocyte mRNAs. A similar correlation between the number of PABP molecules and poly(A) binding sites has been observed in the Spisula oocyte (de Melo Neto et al. 2000).

We further show that depletion of ePAB from extracts accelerates deadenylation of both ARE and non-ARE containing substrates, whereas reconstitution with recombinant ePAB protein restores protection of the poly(A) tail. Strikingly, addition of recombinant ePAB, elevating the level to only twice that of endogenous protein (Fig. 6A), results in complete inhibition of deadenylation. Our data suggest that Xenopus PABP1 and ePAB have similar capacities to protect the poly(A) tails of mRNAs with or without an ARE, at least in vitro (Fig. 6A,C). Whether ePAB has other functions that differ from PABP1 remains to be determined. The dramatic sensitivity of deadenylation to the level of ePAB suggests that endogenous levels of ePAB are very precisely tuned to allow regulated changes in poly(A) tail length in the egg and during early embryogenesis.

A role for ePAB in ARE-mediated deadenylation

ePAB was the highest affinity RNA-binding protein to be eluted (at 1–2 M KCl) from the ARE column (Fig. 3B). This suggests that ePAB might function in ARE-mediated deadenylation. Over ten years ago, it was proposed that 3′-UTR cis-acting elements might destabilize messages by competing PABP off the poly(A) tail (Bernstein et al. 1989). It will be interesting to determine whether a single molecule of ePAB can interact simultaneously with both the poly(A) tail and ARE of an mRNA, as does HuR (Ma et al. 1997).

We observed that only a 10-fold excess of poly(A) specifically inhibits deadenylation of ARE-containing substrates in vitro (Fig. 2D, top panel), suggesting that factors critical for ARE-mediated deadenylation also have high affinity for poly(A). In contrast, 10- to 100fold excess of poly(A) stimulated deadenylation of transcripts that did not contain an ARE (Fig. 2D, bottom panel). We therefore tested whether the concentration dependence of poly(A) inhibition of ARE-mediated deadenylation correlates with the disappearance of any crosslinks by incubating [α-32P]ATP-labeled AT-UTR p(A)+ substrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of poly(A) before crosslinking (data not shown). We found that similar levels of poly(A) (10-fold excess) competed both ARE-mediated deadenylation and the ePAB crosslink, whereas the crosslinking of other ARE-specific bands was enhanced only at 10–100-fold excess poly(A) (data not shown). These data suggest that ePAB could be the critical factor mediating ARE-specific deadenylation. Moreover, the reason that excess poly(A) does not activate deadenylation of the AT-UTR p(A)+ substrate as it does the GC-UTR p(A)+ substrate (Fig. 2D, lanes 11 and 12) may be that other ARE-binding proteins bind and stabilize the poly(A) tail once ePAB is displaced.

Poly(A)-binding proteins have been suggested to function by recruiting deadenylating activities to the poly(A) tail (Sachs and Davis 1989). In yeast, Pab1p not only protects the poly(A) tail but also recruits the PAN deadenylase (Lowell et al. 1992). However, since the immunodepletion of ePAB did not slow the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation (Fig. 6C), it seems unlikely that ePAB actively targets ARE-containing substrates for deadenylation in a fashion analagous to yeast Pab1p. Nor does ElrA play this role, because immunodepletion of greater than 95% of this ARE-specific binding protein likewise did not affect the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation (Fig. 6D, cf. lanes 1–4 with lanes 9–12).

What is the deadenylase active in ARE-dependent deadenylation in vitro? DAN is clearly present and responsible for default deadenylation since its depletion reduced in vitro activity on non-ARE-containing substrates (Fig. 6E). In contrast, DAN depletion did not noticeably reduce the rate of ARE-mediated deadenylation (Fig. 6E, cf. lanes 1–4 with lanes 9–12). This suggests that DAN is not involved, although it is possible that the processive deadenylase activity observed is due to the small amount (less than 5%) of DAN remaining in extract. More work will be required to establish both the identity of the ARE-specific deadenylase and the role of ePAB in modulating its activity during Xenopus early development.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction and use in transcription

AT-GMCSF21–2 and GC-GMCSF21–2 plasmids were constructed and in vitro transcribed to produce AT-GMCSF and GC-GMCSF substrates as previously described (Voeltz and Steitz 1998).

AT-UTRpGEM and GC-UTRpGEM constructs were produced by subcloning the BglII/XbaI 3′-UTR insert from AT-GMCSF21–2 and GC-GMCSF21–2, respectively, into the BamHI/XbaI site present in pGEM 3Z. Poly(A)− AT-UTR and GC-UTR transcripts were transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase from XbaI cut plasmids.

AT-UTRp(A)+ psp and GC-UTRp(A)+psp constructs were produced by subcloning the BglII/SacI insert from AT-GMCSF21–2 and GC-GMCSF21–2, respectively, into the BamHI/SacI site present in pSP73 (Promega). AT-UTR p(A)+ and GC-UTR p(A)+ transcripts are made by T7 transcription from SacI cut plasmids.

0AU (pA)+, 2AU (pA)+, 3AU (pA)+, and 5AU (pA)+ psp constructs were made by annealing complementary oligonucleotides 5′0AU + 3′0AU, 5′2AU + 3′2AU, 5′3AU + 3′3AU, and 5′5AU + 3′5AU, respectively, digesting the annealed products with BglII/XbaI, inserting the resulting fragment into the BglII/XbaI site of AT-GMCSF21–2, and then subcloning the BglII/SacI inserts [now including the 100 nucleotide poly(A) tail] from these 21–2 clones into the XbaI/SacI site of pSP73. 0AU (pA)+, 2AU (pA)+, 3AU (pA)+, and 5AU (pA)+ transcripts were made by transcription of SacI cut plasmids with T7 RNA polymerase.

GST-ePAB-Cterm was constructed by subcloning the 750-bp NheI/XbaI C-terminal fragment of the ePAB coding region, encoding amino acids 386 to 629 (Fig. 3B), into the SmaI site of pGEX-4T2.

6xHis-ePAB

A full-length 6xHis ePAB protein expression clone was made by amplification of ePAB by PCR with primers GBamF2 and GXhoR2 and cloning into BamHI/XhoI site of petPL6xHis (gift from J. Lykke-Andersen).

6xHis HuR

A full-length HuR expression clone was made by digestion of pcDNA-HuR with EcoRI/XbaI (gift from C. Brennan), and ligation of the EcoRI/XbaI HuR cDNA insert into the petPL6xHis vector cut with SmaI.

6xHis PABP1

A full-length PABP1 expression clone was made by amplification of Xenopus PABP1 by PCR of pSP64T-PABP (Zelus et al., 1989) (kind gift from R. Moon) with primers XPABP-F and XPABP-R and cloning into the BamHI/XhoI site of petPL6xHis.

Oligonucleotides/primers

5′GSP, 5′-CAATTCAGACGATGAATGGGATGTT-3′; 3′GSP, 5′-ATCATTGAGCAACATCCCATTCATC-3′; T3ZAP, 5′-TA ACCCTCACTAAAGGGAACAAAAGC-3′; 5′Deg, 5′-GGNTA YGGNTTYGTNCAYTTYGA-3′; 3′Deg, 5′-TTPAAPTGNCC NACPAANACYTT-3′; XPABPF2, 5′-GAGCAGATCTATGAA TCCCAGTGCTCCC-3′; XPABPR, 5′-GTGCCTCGAGTTAA GCAGTTGGCACTCC-3′; GBamF2, 5′-CGGGATCCATGAA TGCAACCGGAGCCGGATATCCGCT-3′; GXhoR2, 5′-CCG CTCGAGTCAGATCAAAGATGGTTGGGCACTT-3′; 5′0AU, 5′-GAAGATCTTAGGTAGGTAGGTAGGTAGGTATTCTA GAGC-3′; 3′0AU, 5′-GCTCTAGAATACCTACCTACCTACC TACCTAAGATCTTC-3′; 5′2AU, 5′-GAAGATCTTAGGTAGGTAGGTATTTATTTATTCTAGAGC-3′; 3′2AU, 5′-GCTCT AGAATAAATAAATACCTACCTACCTAAGATCTTC-3′; 5′3 AU, 5′-GAAGATCTTAGGTAGGTATTTATTTATTTATTCT AGAGC-3′; 3′3AU, 5′-GCTCTAGAATAAATAAATAAATAC CTACCTAAGATCTTC-3′; 5′5AU, 5′-GAAGATCTTATTTA TTTATTTATTTATTTATTCTAGAGC-3′; 3′5AU, 5′-GCTCTAGAATAAATAAATAAATAAATAAATAAGATCTTC-3′.

In vitro transcription and UV-crosslinking

Internally labeled and 5′-capped transcripts for microinjection or incubation in egg extract (Fig. 1) were in vitro transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of m7GpppG or GpppG cap (Pharmacia) and [α-32P]UTP (Amersham) to yield a specific activity of 105 cpm/ng. Capped substrates for UV-crosslinking were made similarly by labelling with [α-32P]UTP or [α-32P]ATP (Amersham). Extracts or fractionated samples were incubated in the presence of internally labeled substrate RNAs (200 kcpm (2–10 ng)/10 μL reaction) and competitor RNA (usually 0.1 mg/mL rRNA) in extraction buffer (EB100, 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2) for 15 min at 22°C. UV-crosslinking (Stratalinker) at 254 nm was performed on ice for 2 × 8600 E. Samples were then digested for 20 min at 37°C with 0.5 mg/mL RNase A and 0.2 U/μL RNase One (Promega), and then resolved by 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

High-speed supernatant production

Extracts of activated X. laevis eggs were prepared according to standard protocols (Leno and Laskey 1991) with some modification. Female frogs were hormonally induced to lay eggs by injection with 500 I.U. chorionic gonadotropin (Sigma). Eggs were collected at room temperature in high-salt Barths (110 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaHCO3, 15 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.4), rinsed in ddH2O, and dejellied in 2% cysteine (pH 7.8). Dejellied eggs were subsequently rinsed four times with Barths (88 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 15 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.4) plus 0.5 mM CaCl2, and activated by addition of 20 μL of 1 mg/mL calcium ionophore (Sigma). After 5 min, the eggs were washed first with Barths and then 3 times with ice cold EB100 + 2 mM β-ME. The final wash included cytochalasin B, leupeptin, pepstatin A, and aprotinin (10μg/mL each). High-speed supernantant (HSS) was made by subjecting the eggs to the following spins in an SW50.1 rotor: packing spin, 1500 rpm for 1 min; crushing spin, 10,000 rpm for 10 min; three clarification spins, 10,000 rpm for 20 min, 100,000 rpm for 60 min, and 100,000 rpm for 30 min, with the cytoplasmic fraction collected after each spin (Leno and Laskey 1991). Glycerol (15% v/v) was added to the HSS prior to freezing by dropping 30 μL aliquots into liquid N2 at a final protein concentration of ∼20 mg/mL.

In vitro assay, microinjections, and RNA analysis

Typically, 10,000 cpm (2 fmol) of gel-purified in vitro transcribed RNA was incubated with 2 μL HSS per 10 μL reaction in EB100. Reactions were incubated at 22°C. At the times indicated, 10-μL samples were removed and frozen at −80°C. Xenopus eggs were obtained by standard procedures (Leno and Laskey 1991) and were incubated in 4% Ficoll in 1/3× MMR (33 mM NaCl, 0.6 mM KCl, 0.3 mM MgCl2, 0.66 mM CaCl2, 1.7 mM Na-HEPES at pH 7.8) prior to cytoplasmic injection with 18 nL (20–40 pg) RNA in ddH2O. Ten eggs were collected per timepoint, frozen at −80°C, and RNA was isolated and analyzed on 6% gels as described previously (Voeltz and Steitz 1998). Positions of poly(A)+ and poly(A)− RNAs indicated in the figures correspond to the positions of co-run unincubated markers.

Purification of ePAB

HSS (8 mL at ∼20 mg/mL) was loaded onto a 5-mL HiTrap heparin-sepharose column (Amersham) in loading buffer (EB100 + 0.05% NP-40 + 1 mM DTT) and washed with 70 mL of loading buffer. RNA binding proteins were then eluted with 10 mL of elution buffer (50 mM Hepes at pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 M KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM DTT) and dialyzed for 4 h against loading buffer containing 10% glycerol. The dialyzed heparin eluate was then incubated with 2 mL of packed volume pre-equilibrated AADA beads (Sigma) for 1 h at RT. The unbound fraction (precleared sample) was subjected to the following RNA affinity chromatography protocol, based largely on Caputi et al. (1999). The AT-UTR and GC-UTR transcripts used to make the RNA affinity columns were synthesized in the absence of cap analog by large-scale (trace-labeled) transcription with T7 RNA polymerase from XbaI linearized templates AT-UTRpGEM and GC-UTRpGEM, respectively. The transcription reaction was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and free nucleotides were removed with a G25 spin column (Pharmacia). The resulting transcripts (4 pmoles) were covalently linked to AADA beads with ≥ 80% efficiency as monitored by trace-labeled substrate. The RNA beads (AT-UTR or GC-UTR) were then incubated with the precleared sample in the presence of 0.5 mg/mL heparin in loading buffer at RT, nutating for 1 h before packing into a column for FPLC. The following steps were performed at 4°C. The agarose column was washed with 25–30 mL loading buffer and bound proteins were eluted with a 40-mL 0.1 to 1 M KCl linear gradient in loading buffer. A 2 M KCl wash followed by a final elution step with EB100 + RNase A (100 mg) were used to elute the remaining bound proteins. Each fraction was dialyzed against loading buffer before protein analysis, in all cases performed by 15% SDS-PAGE. Purified ePAB present in the 2 M elution fraction was excised from the gel, and the sequences of three tryptic peptides were determined by the W.M. Keck Facility at Yale University. Degenerate oligonucleotides 5′Deg and 3′Deg were designed based on two of the determined sequences and used to amplify a 60-nt fragment from a Xenopus ovary ZapII cDNA library (kindly provided by K. Mowry). Gene-specific primers 5′GSP and 3′GSP were used in combination with a vector-specific primer, T3ZAP, to amplify the 5′ and 3′ ends of the ePAB cDNA from the ZAP II cDNA library.

Recombinant protein production, antiserum production, Western analysis, and immunoprecipitation

Recombinant GST-ePAB-Cterm protein was isolated from BL-21 E. coli cells transformed with the GST-ePAB-Cterm vector following induction for 4 h at 30°C with 0.1 mM IPTG. The GST-ePAB-Cterm recombinant protein was eluted from glutathione sepharose-4B (Amersham) with 10 mM glutathione and used to raise antisera to ePAB by subcutaneous injection into rabbits (performed by Yale University's Immunization Services). 6xHis ePAB, 6xHis XPABP1, and 6xHis HuR expression constructs encoding full-length 6xHis ePAB, 6xHis PABP1, and 6xHis HuR proteins, respectively, were transformed into BL-21, and protein expression was induced by 0.1 mM IPTG induction for 2 h at 30°C. Recombinant proteins were subsequently purified by incubation with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) followed by extensive washing, and elution of 6xHis tagged ePAB, PABP1, or HuR protein with 200 mM imidazole. 6xHis-tagged proteins were dialyzed back into EB100 plus 10% glycerol before addition to the in vitro system.

Western analysis was performed using the following concentrations of primary and secondary antibody: 1:2000 anti-ePAB, 1:2000 anti-PABP1 monoclonal (Gorlach et al. 1994), 1:30,000 anti-HuR monoclonal 3A2 (Gallouzi et al. 2000), 1:2000 anti-DAN (Korner et al. 1998), 1:5000 donkey anti-rabbit or 1:5000 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitation and depletion reactions were performed in EB100 by incubating HSS at a 1:5 dilution (500 μL) for 2 h at 25°C with Protein A-Sepharose (PAS) (Amersham) pre-bound to 25 μL of one of the above antibodies or anti-hnRNP D (Dempsey et al. 1998). Equivalent amounts of supernatant and PAS-bound material were fractionated by 15% SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western analysis. Preimmune and antibody-depleted HSS fractions were subsequently analyzed for deadenylation activity. Proteins radiolabeled by transfer from crosslinked RNA substrates were immunoprecipitated by incubating RNase-treated crosslinking reactions (described above) with PAS-bound preimmune serum or antibodies.

Extracts from various stages of Xenopus development (Fig. 5A) were prepared by homogenization of equivalent numbers of oocytes, eggs, or embryos in EB100 buffer. Eggs were fertilized by a standard protocol (Leno and Laskey 1991). Samples were spun at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and supernatants collected. Proteins were fractionated by 15% SDS-PAGE, with unstained low molecular weight markers (BioRad).

GenBank accession no.: The sequence of ePAB has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF338225.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Patel, Dr. J. Lykke-Anderson, Dr. M. Solomon, Dr. A. Weiner, and Dr. B. DeDecker for helpful suggestions on the manuscript. The following provided generous gifts of reagents: Dr. G. Dreyfuss (monoclonal antibody to PABP1), Dr. M. Wormington (polyclonal antibody to DAN), Dr. N. Maizels (polyclonal antibody to hnRNP D), Dr. R. Moon (psp64T-PABP), N. Cahill (Xenopus oocyte nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts), H. Tan (photography), J. Harburger (plasmids 3AU21–2 and 5AU21–2), and Dr. K. Mowry (Xenopus λII ovary cDNA library). Special thanks go to Dr. R. Laskey and T. Mills for help in developing egg extracts active in ARE-dependent deadenylation. This work was supported by grant CA16038 from the National Institutes of Health. J.A.S. is an investigator with HHMI.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL joan.steitz@yale.edu; FAX (203) 624-8213.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.872201.

References

- Audic Y, Omilli F, Osborne HB. Postfertilization deadenylation of mRNAs in Xenopus laevis embryos is sufficient to cause their degradation at the blastula stage. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:209–218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein P, Peltz S, Ross J. The poly(A)-poly(A)-binding protein complex is a major determinant of mRNA stability in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:659–670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvet P, Omilli F, Yannick A-B, Legagneux V, Roghi C, Bassez T, Osborne HB. The deadenylation conferred by the 3′ untranslated region of a developmentally controlled mRNA in Xenopus embryos is switched to polyadenylation by deletion of a short sequence element. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1893–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, C.M. and Steitz, J.A. 2001. HuR and mRNA Stability. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burd CG, Matunis EL, Dreyfuss G. The multiple RNA-binding domains of the mRNA poly(A)-binding protein have different RNA-binding activities. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3419–3424. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi M, Mayeda A, Krainer AR, Zahler AM. hnRNP A/B proteins are required for inhibition of HIV-1 pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1999;18:4060–4067. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Shyu A-B. Selective degradation of early-response-gene mRNAs: Functional analyses of sequence features of the AU-rich elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8471–8482. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Shyu A-B. AU-rich elements: Characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AK, Kahn LE, Bourne CM. Circular polysomes predominate on the rough endoplasmic reticulum of somatotropes and mammotropes in the rat anterior pituitary. Amer J Anat. 1987;178:1–10. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001780102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote CA, Gautreau D, Denegre JM, Kress TL, Terry NA, Mowry KL. A Xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol Cell. 1999;4:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardoff JA, Sachs AB. Differential effects of aromatic and charged substitutions in the RNA binding domains of the yeast poly(A)-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:67–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlin E, Wormington M, Korner CG, Wahle E. Cap-dependent deadenylation of mRNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:1079–1086. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo Neto OP, Walker JA, Sa CM, Standart N. Levels of free PABP are limited by newly polyadenylated mRNA in early Spisula embryogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3346–3353. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.17.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey LA, Hanakahi LA, Maizels N. A specific isoform of hnRNP D interacts with DNA in the LR1 heterodimer: Canonical RNA binding motifs in a sequence-specific duplex DNA binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29224–29229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo RC, Bonanno JB, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Recognition of polyadenylate RNA by the poly(A)-binding protein. Cell. 1999;98:835–845. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan XC, Steitz JA. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3448–3460. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LP, Watson J, Keene JD, Wilusz J. ELAV protein stabilize deadenylated intermediates in a novel in vitro mRNA deadenylation/degradation system. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:188–201. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Wickens M. Poly(A) removal during oocyte maturation: A default reaction selectively prevented by specific sequences in the 3′ UTR of certain maternal mRNAs. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:2287–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR, Tanguay R. Poly(A) binds to initiation factors and increases cap-dependent translation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17166–17173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallouzi I, Brennan CM, Stenberg MG, Swanson MS, Eversole A, Maizels N, Steitz JA. HuR binding to cytoplasmic mRNA is perturbed by heat shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:3073–3078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Fritz DT, Ford LP, Wilusz J. Interaction between a poly(A)-specific ribonuclease and the 5′ cap influences mRNA deadenylation rates in vitro. Mol Cell. 2000;5:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good P. A conserved family of elav-like genes in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach M, Burd CG, Dreyfuss G. The mRNA poly(A)-binding protein: Localization, abundance, and RNA-binding specificity. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:400–407. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange T, de Sa CM, Oddos J, Pictet R. Human mRNA polyadenylate binding protein: Evolutionary conservation of a nucleic acid binding motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:4771–4787. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.12.4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H, Gradi A, Sonenberg N. A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly(A)-binding protein and functions in poly(A)-dependent translation. EMBO J. 1998;17:7480–7489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler SH, Sachs AB. RNA recognition motif 2 of yeast Pab1p is required for its functional interaction with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:51–57. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner CG, Wormington M, Muckenthaler M, Schneider S, Dehlin E, Wahle E. The deadenylating nuclease (DAN) is involved in poly(A) tail removal during the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1998;17:5427–5437. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn U, Pieler T. Xenopus poly(A) binding protein: Functional domains in RNA binding and protein–protein interaction. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:20–30. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagnado C, Brown C, Goodall G. AUUUA is not sufficient to promote poly(A) shortening and degradation of an mRNA: The functional sequence within AU-rich elements may be UUAUUUA(U/A)(U/A) Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7984–7995. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legagneux V, Omilli F, Osborne HB. Substrate-specific regulation of RNA deadenylation in Xenopus embryo and activated egg extracts. RNA. 1995;1:1001–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leno GH, Laskey RA. Methods in cell biology. In: Kay BK, Peng HB, editors. Xenopus Laevis: Practical Uses in Cell and Molecular Biology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 561–578. [Google Scholar]

- Levy NS, Chung S, Furneaux H, Levy AP. Hypoxic stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6417–6423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loflin P, Chen C-Y, Xu N, Shyu A-B. Unraveling a cytoplasmic role for hnRNP D in the in vivo mRNA destabilization directed by the AU-rich element. Genes & Dev. 1998;13:1884–1897. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell J, Rudner D, Sachs A. 3′-UTR-dependent deadenylation by the yeast poly(A) nuclease. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:2088–2099. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WJ, Chung S, Furneaux H. The Elav-like proteins bind to AU-rich elements and to the poly(A) tail of mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3564–3569. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietfeld W, Mentzel H, Pieler T. The Xenopus laevis poly(A) binding protein is composed of multiple functionally independent RNA binding domains. EMBO J. 1990;9:3699–3705. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero LJ, Ashe MP, Sachs AB. The yeast poly(A)-binding protein Pab1p stimulates in vitro poly(A)-dependent and cap-dependent translation by distinct mechanisms. EMBO J. 1999;18:3153–3163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng SS-Y, Chen C-YA, Xu N, Shyu A-B. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–3470. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss T, Hentze MW. Dual function of the messenger RNA cap structure in poly(A)-tail-promoted translation in yeast. Nature. 1998;392:516–520. doi: 10.1038/33192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation in development and beyond. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:446–456. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.446-456.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD. Influence of polyadenylation-induced translation on metazoan development and neuronal synaptic function. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 785–805. [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:423–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.423-450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs AB, Davis RW. The poly(A) binding protein is required for poly(A) shortening and 60S ribosomal subunit-dependent translation initiation. Cell. 1989;58:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N, Shiokawa K, Yamana K. A study on the steady-state population of poly(A) + RNA during early development of Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 1980;77:431–448. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets MD, Fox CA, Hunt T, Woude GV, Wickens M. The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:926–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu A-B, Belasco J, Greenberg M. Two distinct destabilizing elements in the c-fos message trigger deadenylation as a first step in rapid mRNA decay. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:221–231. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standart N, Jackson R. Do the poly(A) tail and 3′ untranslated region control mRNA translation? Cell. 1990;62:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Sachs AB. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum S, Wormington M. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation does not require specific cis-sequences: A default mechanism for translational control. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:2278–2286. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz GK, Steitz JA. AUUUA sequences direct mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay during Xenopus early development. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7537–7545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. A novel poly(A)-binding protein acts as a specificity factor in the second phase of messenger RNA polyadenylation. Cell. 1991;66:759–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90119-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M, Goodwin EB, Kimble J, Strickland S, Hentze M. Translational control of developmental decisions. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational Control of Gene Expression. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 295–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Treisman R. Removal of poly(A) and consequent degradation of c-fos mRNA facilitated by 3′ AU-rich sequences. Nature. 1988;336:396–399. doi: 10.1038/336396a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormington MW, Searfoss AM, Hurney CA. Overexpression of poly(A) binding protein prevents maturation-specific deadenylation and translational inactivation in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1996;15:900–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Good P, Richter JD. The 36-kilodalton embryonic-type cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein in Xenopus laevis is ElrA, a member of the ELAV family of RNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6402–6409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Duckett CS, Lindsten T. iPABP, an inducible poly(A)-binding protein detected in activated human T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6770–6776. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelus BD, Gievelhaus DH, Eib DW, Kenner KA, Moon RT. Expression of the poly(A)-binding protein during development of Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2756–2760. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubiaga A, Belasco J, Greenberg M. The nonamer UUAUUUAUU is the key AU-rich sequence motif that mediates mRNA degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2219–2230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]