Abstract

The biological functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) can be delineated into dioxin response element (DRE)-dependent or -independent activities. Ligands exhibiting either full or partial agonist activity, e.g., 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and α-naphthoflavone, have been demonstrated to potentiate both DRE-dependent and -independent AHR function. In contrast, the recently identified selective AHR modulators (SAhRMs), e.g., 1-allyl-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-indazole (SGA360), bias AHR toward DRE-independent functionality while displaying antagonism with regard to ligand-induced DRE-dependent transcription. Recent studies have expanded the physiological role of AHR to include modulation of hematopoietic progenitor expansion and immunoregulation. It remains to be established whether such physiological roles are mediated through DRE-dependent or -independent pathways. Here, we present evidence for a third class of AHR ligand, “pure” or complete antagonists with the capacity to suppress both DRE-dependent and -independent AHR functions, which may facilitate dissection of physiological AHR function with regard to DRE or non-DRE-mediated signaling. Competitive ligand binding assays together with in silico modeling identify N-(2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)-9-isopropyl-2-(5-methylpyridin-3-yl)-9H-purin-6-amine (GNF351) as a high-affinity AHR ligand. DRE-dependent reporter assays, in conjunction with quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of AHR targets, reveal GNF351 as a potent AHR antagonist that demonstrates efficacy in the nanomolar range. Furthermore, unlike many currently used AHR antagonists, e.g., α-naphthoflavone, GNF351 is devoid of partial agonist potential. It is noteworthy that in a model of AHR-mediated DRE-independent function, i.e., suppression of cytokine-induced acute-phase gene expression, GNF351 has the capacity to antagonize agonist and SAhRM-mediated suppression of SAA1. Such data indicate that GNF351 is a pure antagonist with the capacity to inhibit both DRE-dependent and -independent activity.

Introduction

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor, which is found in the cytoplasm in its latent form bound to heat shock protein 90, and translocates into the nucleus upon ligand-mediated activation (Beischlag et al., 2008). Once inside the nucleus, it binds to the AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT), which displaces heat shock protein 90, and this complex binds to dioxin response elements (DRE) on its direct target genes. Binding to DRE sequences leads to transcription, which was first described for genes that encode for phase I metabolic enzymes, such as CYP1A1/1A2. These enzymes are responsible for the conversion of a number of carcinogens [e.g., benzo(a)pyrene] from procarcinogens into genotoxic intermediates. The most potent prototypic exogenous agonist for the AHR is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), a highly toxic environmental pollutant. Thus the AHR was originally associated with toxic responses at both the cellular and whole-organism level. However, in recent years the AHR has been shown to play an important role in an array of physiological processes. Examination of the physiological role of the AHR was greatly facilitated by the development of Ahr-null mice, leading to the observation of multiple phenotypic defects including immune system dysfunction, reduced reproductive success, and altered liver vascular development (Schmidt and Bradfield, 1996). Further studies have implicated the AHR in additional physiological roles, such as anti-inflammatory endpoints, and T cell differentiation (Quintana et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2009). The activation of the AHR leads to the stimulation of a T cell population that secretes interleukin (IL)-17, thus generating a proinflammatory autoimmune potential (Kimura et al., 2008; Veldhoen et al., 2008). The critical role that the AHR plays in this process was underscored by the ability of the AHR antagonist 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide (CH-223191) to attenuate TH17 cell development in vivo and subsequent secretion of IL-17 and IL-22 (Veldhoen et al., 2009). Another biological endpoint that is influenced by AHR activity is the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells in cell culture (Boitano et al., 2010). The presence of the AHR antagonist StemRegenin 1 [4-(2-(2-(benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-9-isopropyl-9H-purin-6-ylamino)ethyl)phenol; SR1] leads to ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells that maintain an undifferentiated phenotype and retain the ability to engraft immunodeficient mice. These studies underscore the potential of AHR antagonists as therapeutic agents.

This interest in the physiological processes regulated by the AHR has also led to an increased interest in differentiating between classes of AHR ligand and their effects on AHR-mediated transcriptional activity, to modulate possible beneficial roles of the AHR, while inhibiting its potentially toxic effects. A distinct class of ligands has recently been characterized, which are able to bind to the AHR and fail to activate the DRE-mediated responses, yet are able to repress cytokine-induced acute-phase gene expression. These compounds, classified as selective AHR modulators (SAhRMs)1, are interesting in a therapeutic sense, in that the effects of DRE-mediated AHR activity would be repressed while the potentially beneficial anti-inflammatory properties would be retained (Murray et al., 2010c). Two distinct compounds have been characterized as SAhRM, SGA360, and 3′,4′-dimethoxy α-naphthoflavone (αNF); collectively, they have been shown to repress a variety of cytokine-induced acute-phase genes, including SAA1, CRP, LBP, C3, C1S, and C1R (Murray et al., 2010b, 2011). Others also use the term SAhRM in another context, that of a compound that may be used therapeutically in the treatment of breast cancer through AHR-estrogen receptor α cross-talk, this compound exhibits partial agonist activity (Safe and McDougal, 2002). However, in this article the use of the term SAhRM will adhere to the definition in the footnote. After the discovery of this class of compounds, it was hypothesized that a class of AHR antagonists may exist, which not only inhibits the DRE response, but also fails to exhibit SAhRM activity. Though a number of AHR antagonists are known and have been used in past studies, these compounds were characterized only in the context of antagonism of an agonist and thus may only antagonize DRE-mediated AHR activity. Also whether these AHR antagonists exhibit SAhRM activity remains to be explored.

This article establishes that N- [2-(3H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]-9-isopropyl-2-(5-methyl-3-pyridyl)purin-6-amine (GNF351) is an AHR ligand that functions as a “pure antagonist.”2 We have found that this compound displays antagonist activity at a lower concentration than most previously cited AHR antagonists, exhibits no AHR agonist activity, and antagonizes both the DRE-mediated and acute-phase gene repression activities of the AHR. These findings will prove valuable toward further characterization of the AHR and its ability to be activated by various classes of ligands, as well as yielding further insight into its possible role as a therapeutic agent.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

GNF351 was acquired from the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (San Diego, CA). TCDD was kindly provided by Dr. Stephen Safe (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX). 1-Allyl-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-indazole (SGA360) was synthesized as described previously (Murray et al., 2010b). αNF and 6,2′,4′-trimethoxyflavone (TMF) were acquired from Indofine Chemicals (Hillsborough, NJ). 3′-Methoxy-4′-nitroflavone (MNF) was a kind gift from Dr. T. Gasiewicz (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY). Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) was purchased from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany). 2-Methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide) (CH-223191) was purchased from Chembridge Corporation (San Diego, CA). Human recombinant IL-1B was acquired from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Cell Culture.

Huh7 cells, a human hepatoma-derived cell line, as well as the stable reporter cell lines HepG2 40/6 and H1L1.1c2, were maintained in α-minimal essential medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma). Cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37°C, with an atmospheric composition of 95% air and 5% CO2. The human hepatoma-derived reporter line HepG2 40/6 contains the stably integrated pGudluc 6.1 DRE-driven reporter (Long et al., 1998), whereas the murine hepatoma-derived reporter line H1L1.1c2, which was originally obtained from Dr. M. Denison (University of California, Davis, CA) contains the stably integrated pGudluc 1.1 vector (Garrison et al., 1996).

Ligand-Binding Assays.

Binding assays were conducted as described previously (Flaveny et al., 2009). In brief, the AHR photoaffinity ligand 2-azido-3-[125I]iodo-7,8-dibromodibenzo-p-dioxin (PAL) was synthesized as described previously (Poland et al., 1986). To generate hepatic cytosol samples, mouse livers from B6.Cg-Ahrtm3.1 Bra Tg (Alb-cre, Ttr-AHR)1GHP “humanized” AHR mice were homogenized with MENG buffer (25 mM MOPS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3, and 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) with 20 mM sodium molybdate and protease inhibitors (Sigma). Samples were centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000g. Binding assays were conducted in the dark except for the photo-cross-linking of PAL. Next, 0.21 pmol (8 × 105 cpm/tube) of PAL (a saturating quantity) was combined with 150 μg of the hepatic cytosolic protein sample. This combination was then incubated with increasing concentrations of SR1 or GNF351 at room temperature for 20 min. These samples were then photolyzed (402 nm) at 8-cm distance for 4 min, after which 1% charcoal/dextran (final concentration) was incubated at 4°C for 5 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min to remove remaining unbound PAL. Samples were then subjected to gel electrophoresis on an 8% tricine-polyacrylamide gel, after which they were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and visualized by autoradiography. Radioactive bands were cut from the membrane and quantified by gamma-counting.

Cell-Based Luciferase Reporter Assay.

Reporter cell lines used in luciferase reporter assays were grown in six-well plates and treated with AHR ligands dissolved in DMSO (0.1% final concentration) and incubated for 4 h. For antagonism experiments the antagonist was added 5 min before the addition of TCDD. Lysis buffer [25 mM Tris-phosphate, pH 7.8, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM 1,2-diaminhocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100] was then added to each well. The activity of each sample was measured using a TD-20e luminometer using luciferase assay substrate (Promega, Madison, WI) as suggested by the manufacturer.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription.

mRNA was isolated from cell cultures using TRI reagent according to the manufacturer's specifications (Sigma). RNA was converted to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR.

Sequences of primers used for quantitative PCR have been described previously (Murray et al., 2010b). PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix for iQ (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to determine mRNA levels, and analysis was conducted using MyIQ software, in conjunction with a MyIQ-single-color PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Acute-Phase Gene Repression Assay.

A human hepatoma-derived cell line (Huh7) was pretreated for 1 h with AHR ligands and incubated at 37°C in a cell culture incubator. After 1 h, IL-1β and IL-6 were added to the appropriate wells at a concentration of 2 ng/ml for each cytokine. The cells were incubated for an additional 6 h, followed by removal of the media from the cells and 1 ml of TRI reagent was added per well. Quantitative PCR was performed on the samples, with the levels of SAA1 transcripts normalized to L13a.

Mouse Ear Edema Assay.

Mouse ear edema assays were conducted as described previously (Murray et al., 2010b). In brief, 6-week-old male C57BL6/J mice (wild type) were anesthetized. Then, 1.5 μg of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in 50 μl of high-performance liquid chromatography-grade acetone (Sigma) was applied directly to the right ear, followed by application of the test compounds. The left ear received vehicle only. After a 6-h treatment period, the mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation. To quantify levels of inflammation, edema thickness was measured using a micrometer.

AHR Modeling and Ligand Docking.

Ligand binding modeling was conducted as described previously (Bisson et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple comparison post test using Prism (version 5.01) software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) to determine statistical significance between treatments. Data represent the mean change in a given endpoint ± S.E.M. (n = 3/treatment group) and were analyzed to determine significance.

Results

GNF351 Is an AHR Ligand.

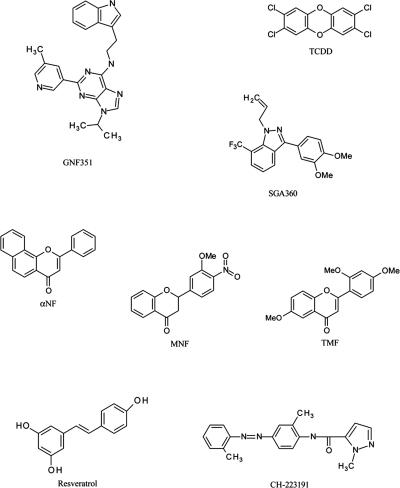

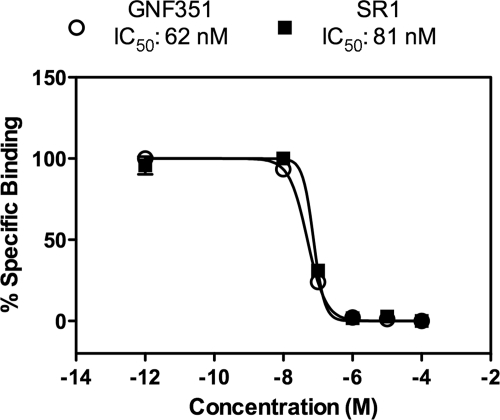

A screen conducted to identify compounds with the capacity to expand CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells in vitro identified SR1, which elicits its activity through antagonism of the AHR (Boitano et al., 2010). In fact, SR1 is a potent AHR antagonist that exhibits species selectivity in that it inhibits human AHR but not mouse or rat AHR. Medicinal chemistry optimization was used to synthesize GNF351, a closely related analog of SR1 that also displayed potent AHR antagonist activity. The structure of GNF351, as well as other AHR agonists and antagonists used or discussed in this study, are found in Fig. 1. To establish that GNF351 is a direct ligand for the AHR, a ligand competition binding assay using the PAL was performed. Figure 2 demonstrates that GNF351 is capable of competing with the photoaffinity ligand for binding to the human AHR and has a relative affinity for the AHR similar to that of SR1. These data demonstrate that GNF351 has a relatively high affinity for the receptor.

Fig. 1.

Structures of the AHR antagonist GNF351 and other AHR ligands used in this study.

Fig. 2.

GNF351 is an AHR ligand. A competition AHR ligand binding assay was conducted as described under Materials and Methods. Mouse liver cytosol expressing humanized AHR was used in combination with increasing concentrations of the test compounds, along with the PAL, at a concentration of 420 pM. Samples were exposed to UV light, analyzed by tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a membrane. The radioactive bands were then excised and quantitated using a gamma-counter. Data represent the percentage of specific binding relative to the absence of a competitor ligand.

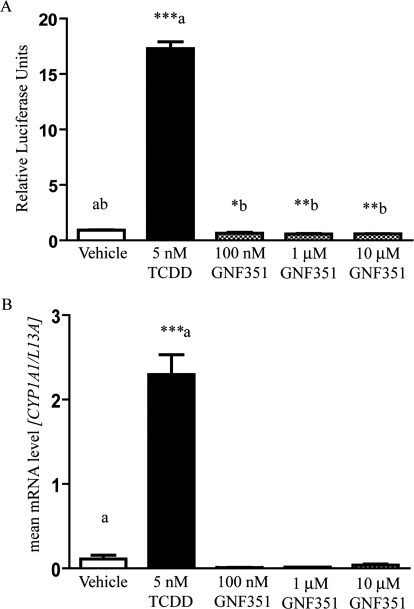

GNF351 Does Not Activate AHR-Dependent DRE-Mediated Transcription.

Because many AHR antagonists also show some degree of agonist activity at higher concentrations, it was necessary to determine whether this was true for GNF351. To determine whether the compound is a partial agonist for the AHR, a transcriptional response assay was conducted using a stable human hepatoma-derived cell line containing the pGudluc 6.1 DRE-driven reporter (HepG2 40/6). Upon treatment with GNF351 for 4 h, no significant agonist activity was observed for 100 nM to 10 μM GNF351 treatments compared with vehicle (Fig. 3A). To determine the effect of GNF351 on levels of endogenous AHR-mediated gene expression, quantitative PCR was performed on HepG2 40/6 cells treated for 4 h with DMSO, TCDD (5 nM), or increasing concentrations of GNF351 (100 nM, 1 μM, and 10 μM). TCDD dramatically induced CYP1A1 mRNA levels, whereas in contrast GNF351 failed to exhibit induction of CYP1A1 even at be highest concentration of 10 μM (Fig. 3B). Indeed, constitutive levels diminished to below basal activity, although this effect was not statistically significant. These results confirmed those generated with the reporter assay system. In addition, these observations suggest that long-term treatment with GNF351 should be an effective means to inhibit basal transcriptional activity of the AHR.

Fig. 3.

GNF351 exhibits a lack of AHR agonist activity at increasing concentrations. A cell-based luciferase reporter assay using human HepG2 40/6 cells was conducted. A, cells were treated with DMSO, TCDD (5 nM), or increasing concentrations of GNF351 for 4 h. B, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed for RNA samples isolated from HepG2 40/6 cells treated with DMSO, TCDD (5 nM), or increasing concentrations of GNF351 for 4 h, and the expression of CYP1A1 levels, normalized to L13a levels, was examined. Each treatment was conducted in triplicate wells. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001), which are relevant to the data sets as labeled in A and compared with control for B. The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a or b).

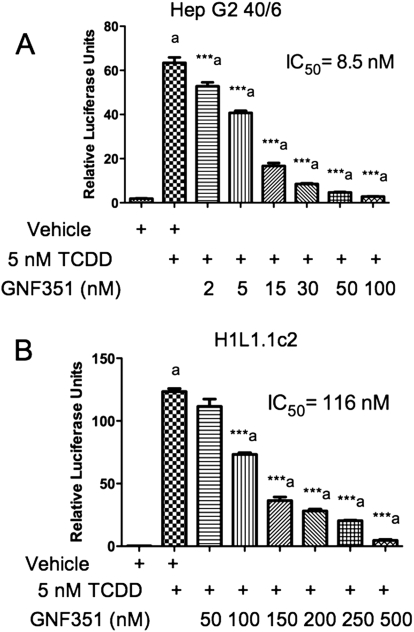

GNF351 Antagonizes Ligand-Mediated AHR Transcriptional Activity.

HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with GNF351 in combination with TCDD for 4 h to determine whether GNF351 inhibits the potent agonist effect seen with TCDD treatment. As the concentration of GNF351 increased, the AHR DRE-mediated response was antagonized in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). To determine whether this effect is species-specific, H1L1.1.1c2 cells were also treated with increasing concentrations of GNF351 in combination with TCDD. Figure 4B shows that GNF351 antagonizes the agonist response in a mouse cell line in a dose-dependent manner, although it took a higher concentration of GNF351 to give the same antagonistic effect as that seen in the HepG2 40/6 cells. This was not unexpected, considering that the murine AHR has a 10-fold higher affinity for TCDD. Taking this into account it would seem that the affinity of GNF351 for the mouse and human AHR are similar. Quantitative PCR was conducted with HepG2 40/6 cells treated with vehicle, TCDD (2 nM), or a combination of GNF351 (100 nM) and TCDD (2 nM) for 4 h. Figure 5 shows that levels of transcribed CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and AHRR decreased with the combined treatment. These three genes have previously been shown to be AHR-responsive (Beischlag et al., 2008). The data further show that the antagonistic effect of GNF351 is not limited to one specific AHR-dependent gene. Considering that a 4-h treatment was able to decrease constitutive AHR target gene expression, it is likely that further repression would be observed with a longer GNF351 treatment.

Fig. 4.

GNF351 antagonizes the DRE-mediated response in AHR in human and murine cells. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of GNF351 in combination with 5 nM TCDD in stable human hepatoma-derived reporter cells (HepG2 40/6) (A) and with 2 nM TCDD in stable murine hepatoma-derived reporter cells (H1L1.1.1c2) (B) for 4 h, after which lysis buffer was added, and a luciferase assay conducted on the lysate. Each data set is the result of triplicate well treatments. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results marked (***, P < 0.001), which are relevant to the data sets as labeled. The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a).

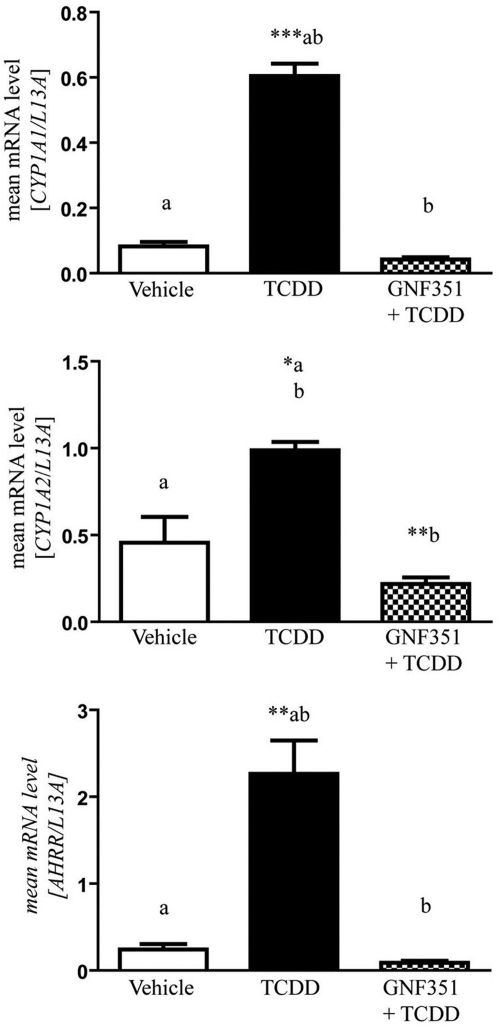

Fig. 5.

GNF351 causes a decrease in levels of AHR-transcribed gene. Quantitative reverse-transcription-PCR was performed using HepG2 40/6 cells treated with DMSO, TCDD (2 nM), and GNF351 (100 nM) with TCDD (2 nM) for 4 h. mRNA levels were assessed for CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and AHRR and normalized to L13a levels. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a or b).

AHR Activity Stimulated by the Endogenous Agonist I3S Is Antagonized by GNF351.

It has been established that the AHR antagonist CH-223191 inhibits TCDD-mediated activation of the AHR but fails to block β-naphthoflavone-mediated activation of the AHR (Zhao et al., 2010). This study then leads to the question as to whether GNF351 can block other AHR ligands as well as TCDD. The indole metabolite 3-indoxyl-sulfate (I3S) was shown to be an endogenous agonist for the AHR (Schroeder et al., 2010). To determine whether GNF351 is capable of antagonizing the DRE response of endogenous agonists, HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of GNF351 and 100 nM I3S. A luciferase assay was used to determine at what concentrations GNF351 suppressed the agonist response. GNF351 antagonized the agonist effect of I3S at all three concentrations examined (Fig. 6). Therefore, GNF351 is capable of antagonizing the DRE-mediated response induced by physiologically relevant endogenous ligands as well as exogenous agonists.

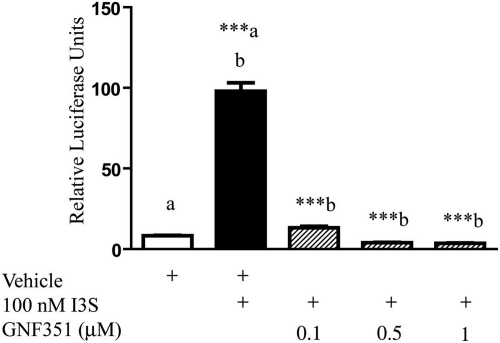

Fig. 6.

GNF351 antagonizes the effect of an endogenous AHR agonist. HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with DMSO, I3S (100 nM), and increasing concentrations of GNF351 with 100 nM I3S. Luciferase readings were taken after cells were lysed. Treatments were conducted in triplicate wells. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results (***, P < 0.001) compared as labeled. The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a or b).

GNF351 Exhibited Sustained Antagonism.

To determine the temporal efficiency of GNF351 antagonism of a DRE-mediated response, HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with GNF351 (100 nM) and cotreated with TCDD (5 nM) over a 24-h time course at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h. GNF351 was able to antagonize TCDD-mediated activation of AHR completely at the 12-h point (Fig. 7). At 16 h, GNF351 still displayed antagonist activity, but was less effective. By 24 h, TCDD also exhibited complete agonist activity, most likely caused by metabolism and/or transport of GNF351 from the cell. This shows that GNF351 is able to antagonize the DRE response for up to 16 h, although it is most effective at 12 h or less. Figure 7B also illustrates this point, showing that GNF351 was still 50% effective at approximately 16 h.

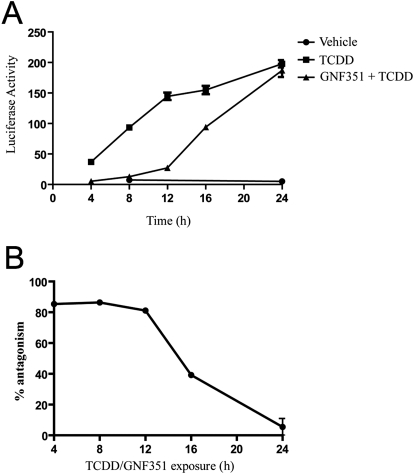

Fig. 7.

GNF351 acts as a DRE antagonist for up to 12 h. A, a time-course treatment was conducted using HepG2 40/6 cells. Cells were treated with DMSO, TCDD (5 nM), or GNF351 (100 nM) and TCDD (5 nM). Treatments were conducted at 4-, 8-, 12-, 16-, 20-, and 24-h time increments. At the end of each time point, cells were harvested using lysis buffer as described under Materials and Methods, and luciferase readings were conducted. Time points for DMSO control were taken at 8 and 24 h. B, data generated in A were replotted to determine the approximate ED50. The average of the TCDD values at each time point was determined, and each GNF351+ TCDD value was divided by the TCDD average to determine percentage of antagonism.

Comparison of GNF351 with Other AHR Antagonists.

GNF351 was compared with other previously published AHR antagonists to test for potency of antagonism and agonist effect at a higher dose. A luciferase reporter assay was conducted using HepG2 40/6 cells treated with a 10 μM concentration of a number of antagonists for 4 h to observe whether these compounds acted as agonists at a high dose. The compounds tested included: GNF351, αNF (Wilhelmsson et al., 1994), TMF (Murray et al., 2010a), MNF (Lu et al., 1995), resveratrol (Casper et al., 1999), and CH-223191 (Kim et al., 2006). Figure 8A, left, demonstrates that αNF displays statistically significant partial agonist activity at 10 μM. GNF351 and the other AHR antagonists tested displayed minimal levels of agonist activity. In Fig. 8A, right, HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with a 40 nM concentration of the antagonists, as well as 5 nM TCDD, for 4 h. GNF351 and MNF showed the most significant antagonism of the DRE response at this low concentration, with CH-223191 also showing a significant level of competition. In contrast, αNF, TMF, and resveratrol failed to inhibit TCDD-mediated gene expression at the concentration tested.

Fig. 8.

Agonist and antagonist properties of various AHR ligands. A, left, HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with 10 μM concentration of various AHR ligands to determine whether each compound displayed agonist activity at a higher concentration. Right, HepG2 40/6 cells were treated with 40 nM AHR ligands plus 5 nM TCDD (except vehicle) to test for antagonistic abilities of each compound at a lower concentration. B, left, H1L1.1.1c2 cells were treated with 10 μM of each AHR ligand to determine whether any exhibited agonist activity. Right, H1L1.1.1c2 cells were treated with 100 nM of each ligand in combination with 2 nM TCDD to determine their antagonistic ability. Each treatment is the result of triplicate wells. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results indicated (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001). The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a or b).

In Fig. 8B, the same compounds were tested for agonist and antagonist activity in a mouse reporter stable cell line (H1L1.c2). For the agonist activity assay (Fig. 8B, left), the compounds were used at a final concentration of 10 μM, whereas in the antagonist comparison, the compounds were tested at 100 nM in combination with 2 nM TCDD. αNF and resveratrol mediated significant agonist activity at this high dose. GNF351 seemed to repress basal levels of AHR activity, as seen with human cells, although this did not prove to be statistically significant. In Fig. 8B, right, GNF351 again was able to antagonize TCDD-driven AHR activity compared with other known antagonists. MNF also exhibited significant repression; in contrast, TMF showed significant induction above TCDD treatment alone. Overall, this assay further shows that GNF351 is a more potent AHR antagonist than previously characterized antagonists.

Acute-Phase Response Pathway Is Not Altered by GNF351.

GNF351 was shown to potently repress AHR transcriptional activity via the DRE-mediated response. To establish whether GNF351 was able to antagonize another gene regulatory network modulated by the AHR, an acute-phase gene repression assay was conducted. Huh7 cells were pretreated for 1 h with vehicle, GNF351 (1 μM), TCDD (10 nM), SGA360 (10 μM), and αNF (10 μM). A combination of IL-1β and IL-6 was then added to all wells at a concentration of 2 ng/ml for each cytokine and treated for an additional 6 h. A control well contained vehicle alone. RNA was isolated from the cells, and specific mRNA levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR. GNF351 in combination with IL-1β and IL-6 showed no decrease in SAA1 levels, indicating that GNF351 effectively failed to mediate repression of the acute-phase response (Fig. 9A). As expected, TCDD and SGA360 (an AHR agonist and a SAhRM, respectively) repressed cytokine-mediated SAA1 expression. αNF, an AHR antagonist with partial agonist activity at 10 μM, was capable of exhibiting a statistically significant level of inhibition of SAA1 expression as has been observed previously (Patel et al., 2009).

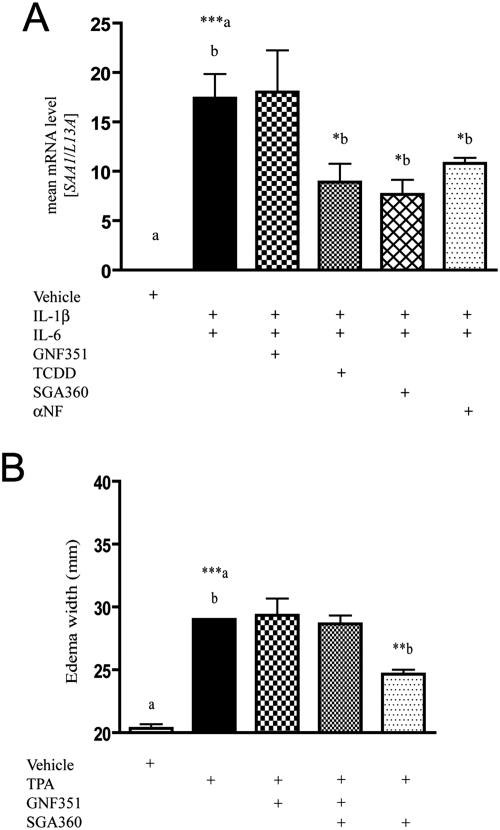

Fig. 9.

GNF351 antagonizes acute-phase response pathways. A, an acute-phase repression assay was conducted in Huh7 cells. Cells were pretreated for 1 h with the following compounds: DMSO (vehicle) alone, DMSO, GNF351 (1 μM), TCDD (10 nM), SGA360 (10 μM), and αNF (10 μM). A combination of IL-1β and IL-6 was then added to all wells, except the vehicle alone (control), at a concentration of 2 ng/ml for each cytokine, and the treatment was continued for an additional 6 h. B, a mouse ear edema assay was conducted as described under Materials and Methods, and data were generated from three 6-week-old male C57BL6/J (wild type) mice. Mice were treated with vehicle (acetone), TPA, GNF351, SGA360, or combinations of these compounds for 6 h. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. with statistically significant results compared as indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). The direct comparisons are shown by the presence of the same letter (a or b).

GNF351 Fails to Repress TPA-Mediated Ear Edema.

To determine whether GNF351 exhibited SAhRM activity in vivo a mouse ear edema assay that we previously characterized was done. In this model TPA is used to induce edema, an effect that can be inhibited by the SAhRM SGA360 (Murray et al., 2010b). Three mice were used per treatment, and treatments were vehicle (acetone), TPA, TPA + GNF351, TPA + GNF351 + SGA360, and TPA + SGA360. Figure 9B reveals that TPA increased edema width, whereas GNF351 failed to decrease edema width, showing that GNF351 has no SAhRM activity, and SGA360 alone repressed TPA-mediated ear edema as has been shown previously (Murray et al., 2010b). It is noteworthy that GNF351 was able to prevent the ability of SGA360 to repress TPA-mediated ear edema, demonstrating that the effects of SGA360 are AHR-dependent. These results indicate that GNF351 can antagonize the activity directed by a SAhRM and illustrates the utility of GNF351 as a means to determine whether SAhRM activity is mediated through an AHR-dependent or -independent mechanism.

GNF351 Interacts with the AHR Binding Pocket in a Homology Model.

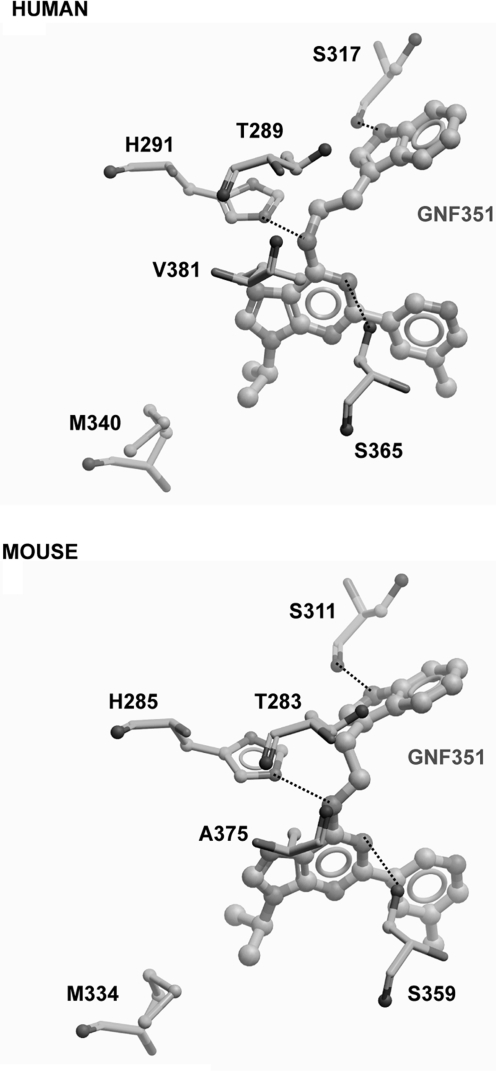

Next, we wanted to test whether GNF351 can efficiently and directly interact with the AHR ligand binding pocket. A computer-generated model of the AHR binding pocket based on its similarity to other PAS (PER/ARNT/SIM)-domain proteins has been established (Bisson et al., 2009). Modeling images were generated for both human and mouse receptor and showed that GNF351 fits into the ligand binding pocket of the AHR for both species (Fig. 10; Supplemental Fig. 1). In this model system, the lower the binding energy value for a particular ligand the higher its affinity for the AHR. Flavones that were previously identified as AHR ligands have binding energies ranging from −4.3 to −2.74 kcal/mol (Bisson et al., 2009). The binding energies for both model systems show that GNF351 binding is energetically favorable in both the human receptor (−7.45 kcal/mol) and mouse receptor (−9.32 kcal/mol). The ligand binding data in Fig. 2 further support the modeling results. The noncovalent interactions between GNF351 and the receptor occur with amino acid residues Ser317, His291, and Ser365 in human and Ser311, His285, and Ser359 in mouse.

Fig. 10.

Homologous AHR binding pocket model for GNF351. In silico modeling was conducted as described previously. GNF351 is shown to bind to human AHR (top) and mouse AHR (bottom).

Discussion

Through the use of an AHR DNA binding mutant it has been established that the AHR can repress cytokine-mediated acute-phase gene expression without binding to a DRE (Patel et al., 2009). In this study it was observed that the partial agonist/antagonist αNF could repress SAA1 expression to a level observed with the potent agonist TCDD. This led to the hypothesis that there are AHR ligands that can mediate acute-phase gene repression without exhibiting significant agonist activity. The AHR ligands 4-[1-allyl-7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-indazol-3yl]benzene-1 (WAY-169916), SGA360, and 3′,4′-dimethoxy-αNF have now been identified as SAhRM that essentially do not exhibit agonist activity, yet can repress cytokine-mediated acute-phase gene expression (Murray et al., 2010b,c, 2011). During chronic diseases such as cancer and rheumatoid arthritis systemic inflammation may occur that leads to an acute-phase response in the liver. The liver can produce large amounts of serum amyloid A that often mediates enhanced systemic inflammatory signaling and can lead to clinically relevant health complications such as amyloidosis. Thus, SAhRM may be of therapeutic value in the treatment of systemic inflammation in chronic inflammatory diseases.

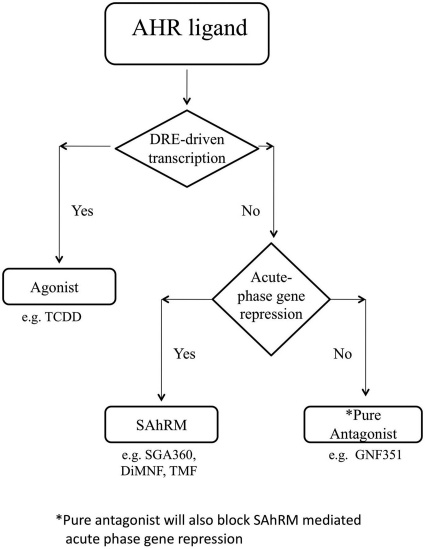

If one only considers the ability of an AHR ligand to block agonist-induced DRE-mediated transcriptional activity as the criteria for an antagonist, then SAhRM would be considered an antagonist. However, the discovery of non-DRE-mediated AHR activity has necessitated that the definition of a “pure” antagonist be redefined to require that the functional definition incorporate non-DRE-mediated AHR activity. Most previously characterized AHR antagonists (e.g., CH-223191, MNF) have not been examined in the context of non-DRE-mediated AHR activity (Lu et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2006), thus it remains to be established if they function as pure antagonists or as inhibitors of DRE-mediated transcription. Thus, previous studies with AHR antagonists may represent an incomplete picture of the effects of comprehensive AHR antagonism. Here, we have demonstrated that GNF351 is a pure antagonist that meets these criteria2. Furthermore this also demonstrates that there are three distinct classes of AHR ligands; agonists, SAhRMs, and pure antagonists. A flow diagram is shown in Fig. 11 illustrating the experimental scheme that leads to the determination of three classes of AHR ligands.

Fig. 11.

Experimental scheme to determine the class of an AHR ligand.

A recent study has shown that AHR antagonists may be selective in their ability to diminish AHR activity (Zhao et al., 2010). Their results indicate that the antagonist CH-223191 is capable of blocking agonist effects mediated by TCDD and certain other halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons, but not activity mediated by flavonoids, such as β-naphthoflavone or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. This study may support the notion that different ligands cause conformational changes in the binding pocket, which may only block competition from certain subsets of ligands. We have demonstrated that GNF351 is able to successfully antagonize the effects of a diverse array of AHR ligands, including TCDD, 3-indoxyl sulfate, and SGA360, which represent three different types of AHR ligands. Though the AHR-dependent transcriptional effects of the compounds tested are blocked, this observation does not preclude the possibility that the activity of other AHR agonists may not be affected.

The characterization of a high-affinity pure antagonist will prove useful for a number of applications. For instance, this distinct class of ligands will allow the biological activity of the AHR to be explored in more depth. Studies using antagonists that effectively block more than one AHR pathway should lead to further insights into the mechanisms of DRE and non-DRE AHR activity. Recently, the AHR antagonist SR1 has been shown to exhibit significant biological effects, such as mediating human hematopoietic stem cell expansion in vitro, and therefore antagonists may also be used to determine underlying physiological mechanisms in which the AHR is involved (Boitano et al., 2010). It is noteworthy that this study did not address whether AHR antagonism in this example occurs through blocking DRE or non-DRE activity; a SAhRM could be used to help address this issue. Also the use of antagonists has already been demonstrated to inhibit IL-6 expression in tumor cells through displacement of the AHR/ARNT heterodimer from the IL-6 promoter and thus may prove useful in therapeutic intervention (DiNatale et al., 2010).

A key feature that the use of GNF351 offers is the lack of agonist activity even at higher doses. Some of the previously known AHR antagonists are imperfect candidates as complete inhibitors of DRE-driven transcription because of the exhibition of partial agonist activity at higher concentrations. One example of this type of antagonist is αNF, which has been shown to exhibit partial agonist activity in both human and murine reporter cells. GNF351 not only fails to induce transcriptional activity at higher concentrations, it also inhibits basal AHR activity. The physiological consequences of decreasing basal activity of AHR have yet to be thoroughly explored. GNF351 exhibits greater potency than a variety of AHR antagonists tested here. Most antagonists require micromolar concentrations to completely inhibit TCDD-mediated transcription. In contrast, as little as 100 nM GNF351 completely inhibited TCDD induction of transcriptional activity in a human cell line. Because GNF351 is effective at lower experimental doses, it is more likely that off-target effects would be minimized by the use of this compound. It is also shown here that GNF351 binds with relatively high affinity to the ligand-binding pocket of the AHR, which should block the binding of an array of exogenous and endogenous ligands. Modeling data presented here shows that GNF351 binds to AHR, but the mechanism by which the compound exhibits its antagonistic activities needs to be determined. Studies of the mechanisms by which ligands, including antagonists, affect AHR function are needed, perhaps after the AHR binding pocket has been successfully crystallized. This is important in the further pursuit of the AHR as a viable drug target for diseases such as cancer and with autoimmune responses. The use of GNF351 in such experiments could allow for receptor activity to be ablated to investigate its possible therapeutic uses.

The existence of pure antagonists will prove useful in various experimental conditions, but it should not be presumed that they would block every aspect of AHR function. For example, it may be unlikely that an antagonist would disrupt protein-protein interactions in which the unliganded AHR participates, presumably in the cytoplasm. An antagonist does not simply ablate the presence of the AHR, and therefore the antagonist-bound receptor should not be considered the same as the absence of receptor. In this study, we have succeeded in identifying a pure AHR antagonist and further expanding what is meant by this term. GNF351 will be useful in a variety of experimental models and should aid in discovering more about the biological functions of the AHR. Currently, the best in vivo models in which to study AHR function involve the repression of AHR expression either in a conditional knockout mouse or Ahr-null mice. Both of these models ablate AHR expression throughout development, and any experiments performed with these mice need to take into account the effects of the long-term absence of AHR expression. In cell culture AHR can be ablated using small interfering RNA, although achieving complete loss of AHR expression is difficult, taking 48 to 72 h. Also, the loss of expression may differ from blocking AHR activity. Therefore, GNF351 will be useful in studying the absence of AHR function for defined time periods for comparison with receptor expression knockdown models. Clearly, future studies are needed to determine the absorption characteristics and half-life of GNF351 for use as an antagonist in vivo. This will allow the receptor to be studied during definitive time points, such as the role of the AHR in development or during disease states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcia H. Perdew for excellent editorial assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant ES04869].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.110.178392.

The online version of this article (available at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The online version of this article (available at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

1 The term SAhRM is defined as an AHR ligand that exhibits essentially no agonist activity with regard to DRE-mediated transcription yet is capable of repressing cytokine-mediated acute-phase gene expression.

2 The term “pure antagonist” is defined as an AHR ligand that exhibits no agonist activity with regard to DRE-mediated transcription, fails to facilitate non-DRE-dependent suppression of gene expression and thus not a SAhRM, and exhibits competitive inhibition of both agonist- and SAhRM-dependent signaling. However, whether a pure antagonist will block all non-DRE-mediated AHR activity will require further studies.

- AHR

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ARNT

- AHR nuclear translocator

- SAhRM

- selective AHR modulator

- TCDD

- 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- DRE

- dioxin response element

- TH

- T helper

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- IL

- interleukin

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- TPA

- 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- PAL

- 2-azido-3-[125I]iodo-7,8-dibromodibenzo-p-dioxin

- GNF351

- N-(2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)-9-isopropyl-2-(5-methylpyridin-3-yl)-9H-purin-6-amine

- SGA360

- 1-allyl-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-indazole

- αNF

- α-naphthoflavone

- MNF

- 3′-methoxy-4′-nitroflavone

- TMF

- 6,2′,4′-trimethoxyflavone

- CH-223191

- 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid(2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide

- SR1

- 4-(2-(2-(benzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-9-isopropyl-9H-purin-6-ylamino)ethyl)phenol

- I3S

- 3-indoxyl-sulfate

- WAY-69916

- 4-[1-allyl-7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-indazol-3yl]benzene-1.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Murray, Kolleri, and Perdew.

Conducted experiments: Smith, Murray, Tanos, and Bisson.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Tellew, Boitano, and Cooke.

Performed data analysis: Smith, Murray, Bisson, and Perdew.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Smith, Murray, Cooke, and Perdew.

Other: Perdew acquired funding for the research.

References

- Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 18:207–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson WH, Koch DC, O'Donnell EF, Khalil SM, Kerkvliet NI, Tanguay RL, Abagyan R, Kolluri SK. (2009) Modeling of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligand binding domain and its utility in virtual ligand screening to predict new AhR ligands. J Med Chem 52:5635–5641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano AE, Wang J, Romeo R, Bouchez LC, Parker AE, Sutton SE, Walker JR, Flaveny CA, Perdew GH, Denison MS, et al. (2010) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science 329:1345–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper RF, Quesne M, Rogers IM, Shirota T, Jolivet A, Milgrom E, Savouret JF. (1999) Resveratrol has antagonist activity on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor: implications for prevention of dioxin toxicity. Mol Pharmacol 56:784–790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNatale BC, Schroeder JC, Francey LJ, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. (2010) Mechanistic insights into the events that lead to synergistic induction of interleukin 6 transcription upon activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem 285:24388–24397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaveny CA, Murray IA, Chiaro CR, Perdew GH. (2009) Ligand selectivity and gene regulation by the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor in transgenic mice. Mol Pharmacol 75:1412–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison PM, Tullis K, Aarts JM, Brouwer A, Giesy JP, Denison MS. (1996) Species-specific recombinant cell lines as bioassay systems for the detection of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-like chemicals. Fundam Appl Toxicol 30:194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Henry EC, Kim DK, Kim YH, Shin KJ, Han MS, Lee TG, Kang JK, Gasiewicz TA, Ryu SH, et al. (2006) Novel compound 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide (CH-223191) prevents 2,3,7,8-TCDD-induced toxicity by antagonizing the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Pharmacol 69:1871–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Naka T, Nohara K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kishimoto T. (2008) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates Stat1 activation and participates in the development of Th17 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:9721–9726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long WP, Pray-Grant M, Tsai JC, Perdew GH. (1998) Protein kinase C activity is required for aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway-mediated signal transduction. Mol Pharmacol 53:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YF, Santostefano M, Cunningham BD, Threadgill MD, Safe S. (1995) Identification of 3′-methoxy-4′-nitroflavone as a pure aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor antagonist and evidence for more than one form of the nuclear Ah receptor in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 316:470–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IA, Flaveny CA, Chiaro CR, Sharma AK, Tanos RS, Schroeder JC, Amin SG, Bisson WH, Kolluri SK, Perdew GH. (2011) Suppression of cytokine-mediated complement factor gene expression through selective activation of the Ah receptor with 3′,4′-dimethoxy-α-naphthoflavone. Mol Pharmacol 79:508–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IA, Flaveny CA, DiNatale BC, Chairo CR, Schroeder JC, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. (2010a) Antagonism of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling by 6,2′,4′-trimethoxyflavone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IA, Krishnegowda G, DiNatale BC, Flaveny C, Chiaro C, Lin JM, Sharma AK, Amin S, Perdew GH. (2010b) Development of a selective modulator of aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor activity that exhibits anti-inflammatory properties. Chem Res Toxicol 23:955–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IA, Morales JL, Flaveny CA, Dinatale BC, Chiaro C, Gowdahalli K, Amin S, Perdew GH. (2010c) Evidence for ligand-mediated selective modulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity. Mol Pharmacol 77:247–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RD, Murray IA, Flaveny CA, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. (2009) Ah receptor represses acute-phase response gene expression without binding to its cognate response element. Lab Invest 89:695–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland A, Glover E, Ebetino H, Kende A. (1986) Photoaffinity labelling of the Ah receptor. Food Chem Toxicol 24:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E, Caccamo M, Oukka M, Weiner HL. (2008) Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 453:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S, McDougal A. (2002) Mechanism of action and development of selective aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulators for treatment of hormone-dependent cancers (Review). Int J Oncol 20:1123–1128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JV, Bradfield CA. (1996) Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 12:55–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JC, Dinatale BC, Murray IA, Flaveny CA, Liu Q, Laurenzana EM, Lin JM, Strom SC, Omiecinski CJ, Amin S, et al. (2010) The uremic toxin 3-indoxyl sulfate is a potent endogenous agonist for the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochemistry 49:393–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Christensen J, O'Garra A, Stockinger B. (2009) Natural agonists for aryl hydrocarbon receptor in culture medium are essential for optimal differentiation of Th17 T cells. J Exp Med 206:43–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, Stockinger B. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453:106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson A, Whitelaw ML, Gustafsson JA, Poellinger L. (1994) Agonistic and antagonistic effects of α-naphthoflavone on dioxin receptor function. Role of the basic region helix-loop-helix dioxin receptor partner factor Arnt. J Biol Chem 269:19028–19033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Degroot DE, Hayashi A, He G, Denison MS. (2010) CH223191 is a ligand-selective antagonist of the Ah (Dioxin) receptor. Toxicol Sci 117:393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.