Abstract

In plants, the cell wall is a major determinant of cell morphogenesis. Cell enlargement depends on the tightly regulated expansion of the wall, which surrounds each cell. However, the qualitative and quantitative mechanisms controlling cell wall enlargement are still poorly understood. Here, we report the molecular and functional characterization of LRX1, a new Arabidopsis gene that encodes a chimeric leucine-rich repeat/extensin protein. LRX1 is expressed in root hair cells and the protein is specifically localized in the wall of the hair proper, where it becomes insolubilized during development. lrx1-null mutants, isolated by a reverse-genetic approach, develop root hairs that frequently abort, swell, or branch. Complementation and overexpression experiments using modified LRX1 proteins indicate that the interaction with the cell wall is important for LRX1 function. These results suggest that LRX1 is an extracellular component of a mechanism regulating root hair morphogenesis and elongation by controlling either polarized growth or cell wall formation and assembly.

Keywords: Cell morphogenesis, cell polarization, cell wall, extensin, LRRs, root hair

Plant cells are surrounded by a rigid wall, which confers stability and protection to the cell but also restricts its enlargement and prevents cell migration. Consequently, many aspects of plant development are dependent on the proper regulation of cell wall expansion. The primary plant cell wall is composed of a network of cellulose microfibrills, which are interconnected with xyloglucan chains and embedded in a hydrated pectin matrix (Carpita and Gibeaut 1993). Three main classes of cell wall structural proteins have been described as follows: proline-rich-proteins (PRPs), glycine-rich-proteins (GRPs), and hydroxyproline-rich-glycoproteins (HRGPs), also called extensins (Keller 1993; Showalter 1993; Cassab 1998). Extensins contain Ser-Hyp4 pentapeptide repeats, which are glycosylated by galactose and arabinosyl side chains (Wilson and Fry 1986). Extensin gene expression is induced or up-regulated in tissues under tensile stress (Shirsat et al. 1996), strong mechanical pressure (Keller and Lamb 1989), upon wounding (Wycoff et al. 1995), and pathogen infection (Garcia-Muniz et al. 1998). Subsequent protein insolubilization has been interpreted as a mechanism to strengthen the cell wall in which an increased resistance is required (Fry 1986). Extensins might also be more generally involved in plant development as regulators of cell wall expansion (Carpita and Gibeaut 1993) or as linkers between the cell wall and the plasma membrane (Knox 1995).

In recent years, several key enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis and remodeling have been identified, clarifying how cell wall expansion proceeds (for review, see Nicol and Höfte 1998; Cosgrove 1999; Delmer 1999). However, the molecular mechanisms that locally regulate cell wall modifications and relay information on the cell wall status to the cytoplasm, are still largely unknown. Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) proteins, which mediate protein–protein interactions in many different cellular processes (Kobe and Deisenhofer 1994) might also have a regulatory or signaling function in the expanding plant cell wall. In plants, LRRs form the extracellular domain of several receptor-like kinases involved in development, hormone perception, and pathogen response (Song et al. 1995; Torii et al. 1996; Clark et al. 1997; Li and Chory 1997; Jinn et al. 2000). The extracellular polygalacturonase inhibiting proteins (PGIPs), which have a role in plant defense and possibly during development, are also LRR proteins (Jones and Jones 1997).

Root hairs have been established as a useful model to study cell expansion and cell shape specification in higher plants (Schiefelbein 2000). Root hairs are made of single cells, are easily accessible, and follow a precise morphogenetic pathway providing landmarks to assess developmental alterations. Root hairs are formed by specialized rhizodermal cells (trichoblasts), which, by reorienting cell expansion, form a long tubular structure almost perpendicular to the main cell axis. In Arabidopsis, root hair initiation takes place at the basal end of the trichoblast, when these cells enter the differentiation zone (Dolan et al. 1994). The root hair emerges as a bulge, which subsequently elongates by tip growth. The latter represents an extreme case of asymmetric growth and relies on a precise cytoplasmic polarization, restricting exocytosis of new material to the small apical area, in which the actual cell expansion occurs. The actin cytoskeleton, microtubules, and gradient of calcium concentration over the plasma membrane at the tip have been shown to be important for root hair growth and orientation (Schiefelbein et al. 1992; Bibikova et al. 1997, 1999; Wymer et al. 1997; Miller et al. 1999).

Genetic dissection of root hair development in Arabidopsis has identified several loci specifying root hair morphogenesis (Schiefelbein and Somerville 1990; Schiefelbein et al. 1993; Masucci and Schiefelbein 1994; Grierson et al. 1997; Parker et al. 2000; Favery et al. 2001). However, only two of the genes encoded at those loci have been cloned to date, RHD3, which encodes a GTP-binding protein acting in vacuole biogenesis (Galway 1997; Wang 1997) and KOJAK, a cellulose synthase-like protein necessary for cell wall biosynthesis in root hairs (Favery et al. 2001). The rhd3 mutation is epistatic and results in plants with a short stature with waving root hairs, whereas the kojak mutation results in root hairs with a weak cell wall that ruptures soon after root hair initiation.

Here, we report the molecular and functional characterization of LRX1, a new Arabidopsis gene encoding a chimeric, extracellular protein containing both a LRR and an extensin protein domain. LRX1 expression is restricted to root hair cells and LRX1 is localized in the root hair proper, where it is tightly associated with the cell wall. The analysis of lrx1-null mutants and plants overexpressing a truncated form of LRX1 revealed that this gene is an important factor in the process of root hair development. These results suggest that LRX1 represents a cell wall component involved in the regulation of cell expansion.

Results

LRX1 encodes a LRR/extensin chimeric protein

Computer analysis suggested that the tomato extensin gene TOML-4 (Zhou et al. 1992), in fact, encodes a LRR/extensin protein (Jones and Jones 1997). We obtained the full-length gene by screening a tomato genomic library with the PCR-amplified 5′ region of the TOML-4 gene. Subsequent sequence analysis confirmed that TOML-4 encodes a protein with an amino-terminal LRR domain in frame with a carboxy-terminal extensin domain (data not shown). Comparison with entries in the Arabidopsis DNA database revealed a total of 11 genes homologous to the TOML-4 LRR domain. The gene with the highest homology to TOML-4 was named LRX1 (LRR/EXTENSIN1).

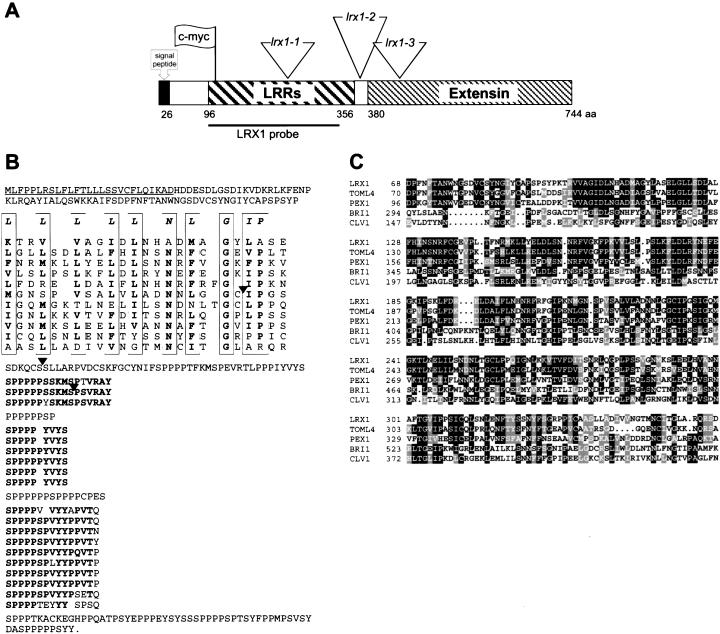

LRX1 is located on chromosome I, BAC clone F12F1, and consists of an intronless ORF of 2235 bp, encoding a protein of 744 amino acids. Comparison between the LRX1 genomic sequence isolated from an Arabidopsis genomic library and the cDNA sequence amplified by RACE–PCR confirmed the absence of introns. The position of the transcription start and the polyadenylation signal were localized 36 nt upstream and 2442 nt downstream of the ATG protein translation start, respectively (data not shown). The protein primary structure consists of a predicted signal peptide, a short domain that shows no significant homology to known functional motifs, a LRR domain of 260 amino acids and a carboxy-terminal extensin-like domain of 363 amino acids (Fig. 1A,B). The LRR domain contains 11 repeats of 22–25 residues matching the plant extracytoplasmic LRR consensus sequence LxxLxxLxxLxLxxNxLxGxIPxx (Jones and Jones 1997) (Fig. 1B). The LRR domain of LRX1 shares 53% of sequence identity with the amino-terminal domain of PEX1, a maize pollen-specific LRR/extensin whose LRR domain went unnoticed (Rubinstein et al. 1995a), and 73% with the LRR domain of TOML-4 (Zhou et al. 1992) (Fig. 1C). LRX1 also shows a strong similarity with 10 other putative Arabidopsis proteins, all containing a conserved LRR domain and a variable extensin domain (data not shown). Numerous SerPro4 motifs, which are organized in three different higher-order repeat sequences [SP5(Y/S)SKMSPSVRAY; SP4YVYS; SP4(S/V)P(V/L)YYPxVTx, where x is P, Q, S, N, or Y], constitute much of the carboxy-terminal domain of LRX1 (Fig. 1B). The extensin domain contains nine Tyr-x-Tyr triplets, which are considered as potential sites for either intra- or intermolecular covalent cross-linking (Kieliszewski and Lamport 1994). The LRX1 gene was found only once in the Arabidopsis genome sequence and Southern blot analysis confirmed that LRX1 is a single copy gene (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Structure of the LRX1 gene. (A) Schematic representation of the gene indicating the different domains of the encoded protein, the En-1 element insertion sites in the three mutant lines (triangles), the position of the c-myc tag used for immunolocalization of LRX1 (flag), and the fragment used as probe in hybridization experiments (LRX1 probe). (B) Deduced amino acid sequence of the LRX1 gene. The predicted signal peptide is underlined and the different domains have been arranged to highlight their organization. The LRRs are aligned on the plant extracellular LRR consensus sequence (first line in the frames). The conserved amino acids are indicated in bold. The diverse higher-order repeats of the extensin domain are aligned and the amino acids conserved within those repeats are indicated in bold. Black arrowheads indicate the position of the three En-1 insertions shown in A. (C) Alignment of the LRR domains of LRX1, PEX1 (maize, Z34465), TOML-4 (tomato, M76671), CLV1 (Arabidopsis, U96879), and BRI1 (Arabidopsis, AF017056). Identity and similarity are indicated by black and grey shading, respectively.

LRX1 is expressed in differentiating root hair cells

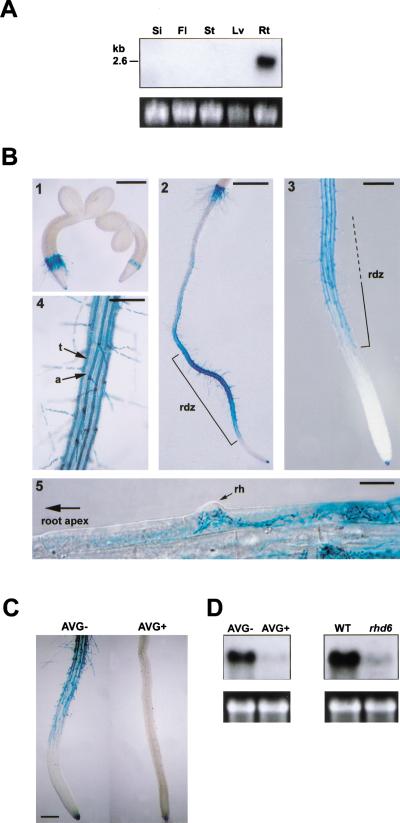

The expression pattern of LRX1 was determined by Northern hybridization and analysis of transgenic plants harboring the bacterial uidA gene under the control of the LRX1 promoter (pLRX1∷GUS). Northern hybridization revealed a single band of ∼2.6 kb exclusively present in root RNA extracts (Fig. 2A) corresponding in size to the LRX1 cDNA obtained by RACE–PCR. The expression of the pLRX1∷GUS construct was analyzed in 10 independent transgenic lines. Consistent with the data obtained with Northern hybridization, GUS activity was only detected in roots and was first observed in the epidermal cells of the collet transition zone, in which the first root hairs are formed shortly after germination (Fig. 2B, panel 1). Upon further development of the seedlings, expression was observed to be restricted to trichoblasts along the differentiation zone (Fig. 2B, panels 2–4). GUS activity was first detected in cells in which a small bulge could be identified as an emerging root hair (Fig. 2B, panel 5) and persisted during root hair formation. In mature parts of the root, GUS activity gradually faded. No expression was detected in either the meristem region or the elongation zone of the root, whereas columella cells in the root cap were stained (Fig. 2B, panel 3). The same GUS expression pattern was reiterated in lateral roots (data not shown).

Figure 2.

LRX1 expression pattern (A) Organ-specific expression of LRX1. Total RNA was extracted from green siliques (Si), flowers and flower buds (Fl), inflorescence stems (St), and rosette leaves (Lv), of 35–40-day-old wild-type Columbia plants. Roots (Rt) were harvested from 14-day-old seedlings grown vertically on MS medium. For Northern analysis, 10 μg of total RNA was hybridized with a 32P-labeled LRX1 probe and 25S rRNA was used as loading control (bottom). (B) Transgenic seedlings containing the LRX1 promoter fused to the uidA gene were histochemically stained at different developmental stages to reveal the tissue-specific expression of LRX1. GUS activity (blue staining) was first detected in the epidermal root hair forming cells of the collet region, 2 d after germination (1). In 4-day-old seedlings, GUS activity was mainly detected in rhizodermal cells of the root differentiation zone (rdz) and in the root cap (2,3). In the differentiation zone, only trichoblast cell files (t), which alternate with atrichoblast cell files (a), show GUS activity (4). GUS expression is first visible within cells undergoing root hair (rh) initiation (5). Bars, 400 μm (1,3), 800 μm (2), 200 μm (4), and 20 μm (5). (C) GUS expression in AVG-treated seedlings. AVG treatment (AVG+) prevented root hair formation and blocked GUS expression compared with control seedlings (AVG−). Bar, 250 μm. (D) LRX1 expression in AVG-treated seedlings and rhd6 mutants. Total RNA was extracted from seedlings grown on MS medium containing the ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor L-α-(2-amino-ethoxyvinyl)glycine (left, AVG+), from rhd6 mutants, which do not develop root hairs (right, rhd6), and from wild-type control plants grown on normal MS medium (left, AVG−; right, WT). Total RNA (10 μg) was used for Northern analysis. 25S rRNA was used as loading control (bottom).

Because root hair development is dependent on and promoted by ethylene, we tested the expression of the reporter gene in pLRX1∷GUS seedlings treated with the ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor L-α-(2-amino-ethoxyvinyl)gly (AVG) (Tanimoto et al. 1995). AVG treatment almost completely prevented both root hair development and GUS expression in pLRX1∷GUS seedlings compared with untreated control plants (Fig. 2C). Endogenous LRX1 gene expression was also almost completely abolished in AVG-treated wild-type plants (Fig. 2D, left). Similarly, LRX1 expression was strongly reduced in the almost root hairless rhd6 mutant (Masucci and Schiefelbein 1994) (Fig. 2D, right). These results confirm that LRX1 expression is highly correlated with root hair development.

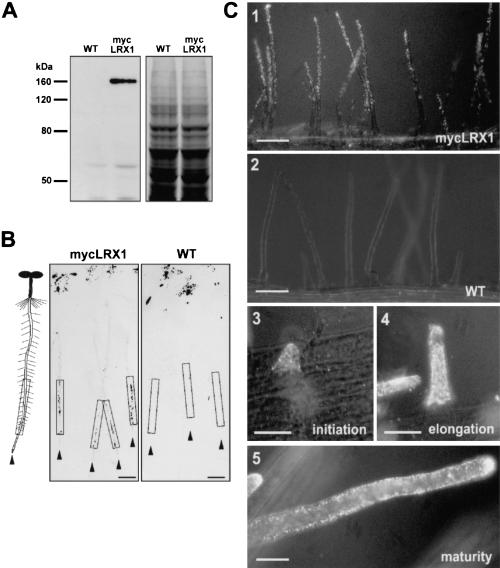

LRX1 is located in the root hair proper and is insolubilized during development

To determine the cellular localization of LRX1, transgenic plants expressing a c-myc-tagged LRX1 protein under the control of the LRX1 promoter sequence (mycLRX1 plants) were generated (Fig. 1A). This approach was used to specifically detect LRX1, considering the number of related LRX genes whose products might cross-react with antibodies raised against LRX1. On protein blots, anti-c-myc monoclonal antibodies (myc-mAbs) detected a single polypeptide of 160 kD in root protein extracts of mycLRX1 plants but not of wild-type plants (Fig. 3A). The difference between the apparent molecular mass and the calculated size of the LRX1 protein sequence (85 kD) is probably a result of extensive glycosylation of the extensin domain. To investigate the organ distribution of the LRX1 protein, we performed tissue-print immunolocalization of mycLRX1 in young seedlings. In mycLRX1 plants, signals were detected along the root at positions corresponding to the differentiation zone, whereas no signal above background was detected in control plants (Fig. 3B). The tagged protein was also localized at the cellular level by whole-mount immunolabeling. Root hairs proper were specifically labeled, whereas the rest of the trichoblast cells were not decorated (Fig. 3C, panels 1–3). In agreement with the pLRX1∷GUS expression pattern, no labeling was observed in either atrichoblast, meristematic, or elongating cells (data not shown). MycLRX1 was detected throughout root hair development as follows: during initiation (Fig. 3C, panel 3), elongation (Fig. 3C, panel 4) and even after root hair maturation (Fig. 3C, panel 5). Labeling was evenly detected all over the root hair structure, indicating a regular distribution of the protein (Fig. 3C, panel 1). Thus, whole-mount immunolocalization revealed that mycLRX1 is present specifically in root hairs at all developmental stages. However, in tissue-print analysis, mycLRX1 was detected only along the differentiation zone. This difference suggests that LRX1 is soluble in the early stages of root hair development and becomes insolubilized in later stages. As HRGPs have been shown to be insolubilized in the cell wall by oxidative cross-linking (Fry 1982; Bradley et al. 1992) the LRX1 extensin domain might mediate the interaction of mycLRX1 with other cell wall components during root hair development.

Figure 3.

Identification and immunolocalization of the LRX1 protein by epitope tagging. (A) Protein gel blot of root extracts from wild-type (WT) and transgenic (mycLRX1) plants expressing the c-myc-tagged LRX1 protein under control of the LRX1 promoter. Blots were incubated with the mouse myc-mAbs (left) and a duplicate gel was stained with Coomassie blue to test for equal loading (right). (B) Tissue print immunoblot. Four-day-old wild-type (WT) and transgenic mycLRX1 (mycLRX1) seedlings were pressed on nitrocellulose membranes to transfer soluble proteins. A scheme of seedlings at the same scale as the blots is represented at left of the panels for orientation. Arrowheads indicate the position of each root tip and frames delimit the root differentiation zone. The dark spots at the top of the membrane were caused by anthocyanins of the cotyledons also transferred onto the membrane. Signals were visible in the differentiation zone of mycLRX1 plants (mycLRX1) but not in controls (WT). Bars, 1 mm. (C) Whole-mount immunolocalization of mycLRX1. Three-day-old wild-type (WT) and mycLRX1 (mycLRX1) seedlings were fixed and immunolabeled with myc-mAbs. The c-myc epitope was found to be associated with root hairs in mycLRX1 (1), but not in wild-type (2) seedlings. Labeling was visible from root hair initiation (3), throughout root hair elongation (4), and after root hair maturation (5). Bars, 100 μm (1,2), 25 μm (3–5).

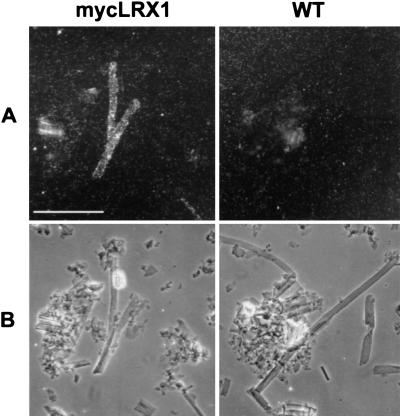

To determine whether mycLRX1 is immobilized in the cell wall, root cell walls were purified by extraction in phenol-acetic acid to remove soluble proteins as well as cytoplasmic and membrane components. The insoluble cell wall fraction was then immunolabeled with myc-mAbs. Elongated thin-walled structures, identified as root hair debris, were regularly decorated in mycLRX1 plant material (Fig. 4A,B, left), whereas such structures were not labeled in wild-type material (Fig. 4A,B, right). This indicates that a significant amount of mycLRX1 protein strongly interacts with the root hair cell wall and cannot be extracted.

Figure 4.

Immunodetection of mycLRX1 in purified cell walls. Wild-type (WT) and mycLRX1 (mycLRX1) roots were ground in liquid nitrogen and cell walls were purified before immunolabeling with myc-mAbs and gold-conjugated secondary antibodies. After silver enhancement, the preparation was observed under epipolarized light (A) to reveal the labeling, or transmitted light (B) to identify cell types. Tubular structures, identified as root hair debris were regularly labeled in mycLRX1 material, whereas such structures were not decorated in wild-type preparations. Bar, 100 μm.

Identification and characterization of transposon-tagged lrx1 mutants

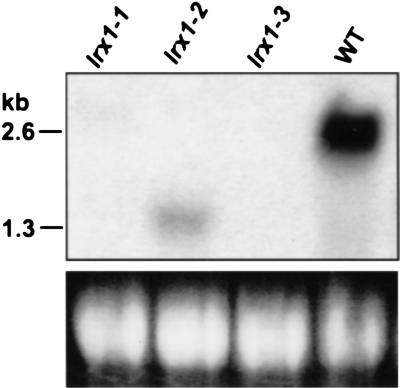

To investigate the biological function of LRX1, we identified lrx1 loss-of-function mutants by screening an En-1-mutagenized Arabidopsis population. Three independent lines were identified that carried an insertion in the LRX1 gene and these were named lrx1-1, lrx1-2, and lrx1-3, according to the position of the insertion in the sequence (Fig. 1A). LRX1 expression was tested in the three mutant lines by Northern hybridization. No transcript could be detected in the lines lrx1-1 and lrx1-3, whereas in the line lrx1-2, a shorter LRX1 transcript of 1.3 kb was detected at a much lower level compared with wild type (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

LRX1 expression in lrx1 mutants. Total RNA was extracted from 14-d-old seedlings grown vertically on the surface of MS plates. Seedlings from wild-type Columbia (WT) and from each of the three lrx1 mutant lines (lrx1-1, lrx1-2, and lrx1-3) were used. Total RNA (20 μg) was loaded per lane and the membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled LRX1 probe (see Fig. 1A). 25S rRNA was used as loading control (bottom).

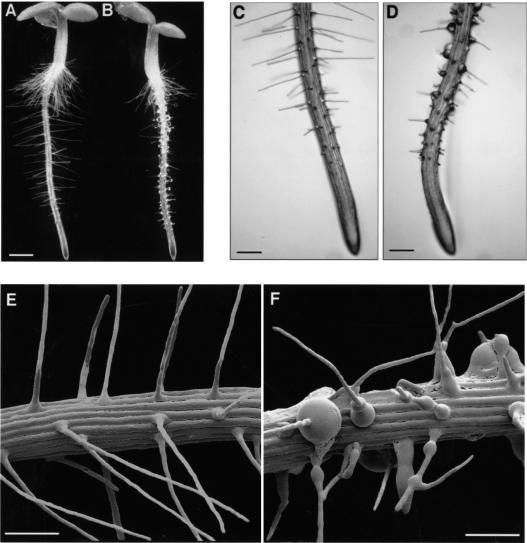

Root hair development was compared between wild-type and homozygous mutant plants grown vertically on the surface of agar plates. In contrast to wild-type plants, which showed an even pattern of straight and thin root hairs (Fig. 6A,C,E), lrx1 mutants exhibited an extremely irregular root hair development (Fig. 6B,D,F). The majority of the root hairs did not elongate completely and was shorter at maturity than wild-type root hairs (Fig. 6A–B). lrx1 root hair development was often arrested early after initiation, resulting in short stumps. Root hairs that proceeded further, frequently branched with one or two lateral branches emerging from the central stalk (Fig. 6F). lrx1 root hairs frequently showed swelling, either at the basis or along the main stalk, resulting in root hairs of irregular diameter or, in some extreme cases, in a spherical structure severalfold the normal diameter of a root hair (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6.

lrx1-1 mutant phenotype. Wild-type and lrx1-1 mutant seedlings were grown vertically for 3 d on the surface of MS plates and were either observed under a stereomicroscope with dark field illumination (A,B), transmitted light (C,D), or frozen in liquid nitrogen and investigated at low temperature in a scanning electron microscope (E,F). Compared with wild type (A,C,E), the lrx1-1 mutant (B,D,F) has fewer fully elongated root hairs (B), and mutant root hairs frequently have a swollen basis (D,F), show an irregular diameter and often branch (F). The three lrx1 mutant lines had identical phenotypes. Bar, 1 mm (A,B), 350 μm (C,D), 250 μm (E,F).

Trichoblast morphology, except for the hair itself, was not affected and the basal location of the root hair initiation site (Dolan et al. 1994) was preserved. Root hair differentiation also took place at the same distance from the root tip in the mutants compared with the wild type, and a similar number of root hairs was initiated (Fig. 6C,D). Furthermore, the alternate pattern of trichoblast and atrichoblast cell files as well as the inner anatomical organization of the root was indistinguishable between mutant and wild-type roots (data not shown). The three mutant lines displayed the same phenotype and can be considered as complete loss-of-function mutants, in view of the absence of LRX1 transcript in two of the lines. lrx1 mutants grew normally on soil and did not display any defect beside the altered root hair development. The mutant phenotype segregated in a 1:3 ratio in the progeny of a lrx1 heterozygous plant, indicating that the lrx1 mutation is recessive.

A complementation test was performed by crossing a transgenic mycLRX1 plant into the lrx1 mutant background. Analysis of the F2 and F3 progeny revealed that the mycLRX1 construct fully rescued the mutant phenotype (data not shown). This result shows that the lrx1 mutation is responsible for the observed root hair phenotype. It also shows that the mycLRX1 transgene is correctly expressed and encodes a fully functional protein, which is localized in the correct subcellular compartment.

A complementation test with previously isolated rhd1, rhd2, rhd3, and rhd4 root hair development mutants (Schiefelbein and Somerville 1990) was performed. The analysis of the F1 seedlings of the corresponding crosses revealed that lrx1 is not allelic to any of the rhd mutants. It was also excluded that lrx1 is allelic to the other described mutants affecting root hair morphogenesis (tip1, Schiefelbein et al. 1993; cow1, Grierson et al. 1997; shv1 to shv3, cen1 to cen3, bst1, and scn1, Parker et al. 2000) by comparing the position of the loci on the genetic map. Therefore, LRX1 constitutes a new gene involved in root hair development.

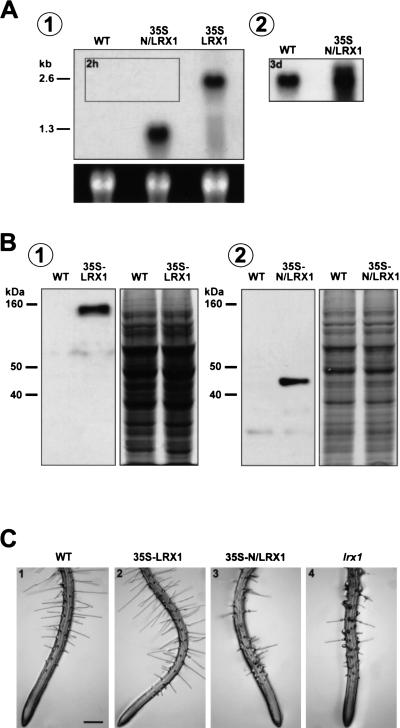

Constitutive overexpression of full-length and truncated LRX1 proteins

The LRX1 gene under the control of the 35S CaMV promoter was transformed into wild-type Arabidopsis. Several transgenic lines displayed an LRX1 transcript level much higher than wild-type plants and one representative line was selected for further analysis. The higher LRX1 expression in the roots of the 35S-LRX1 transgenic plants compared with wild type was demonstrated by Northern hybridization and protein immunoblotting (Fig. 7A,B). For immunodetection, an anti-LRX1 polyclonal antiserum raised against the LRR domain of LRX1 was used. The phenotype of the 35S-LRX1 plants was analyzed on MS plates and on soil. No difference in growth or morphology could be detected between transgenic and wild-type plants, indicating that an excess of LRX1 does not affect plant development (Fig. 7C, panel 2). Complementation of the lrx1 mutant by the 35S-LRX1 construct confirmed that the overexpressed LRX1 is functional (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Overexpression of the complete (35S-LRX1) and truncated (35S-N/LRX1) LRX1 protein. The sequences coding for the full-length or truncated LRX1 protein were transformed into Arabidopsis under the control of the 35S CaMV promoter. (A) Total RNA was extracted from roots of 14-d-old wild-type seedlings (WT), transgenic seedlings overexpressing the truncated LRX1 (35S-N/LRX1) and transgenic seedlings overexpressing the complete LRX1 (35S-LRX1). Total RNA (5 μg) was loaded per lane and the membrane was hybridized with a 32P- labeled LRX1 probe (Fig. 1A). The blot was exposed first for 2 h (1) and the framed area in 1 was further exposed for 3 d (2). Transgene transcript levels were more than 100-fold higher than the endogenous LRX1 transcript. The bottom panel shows 25S ribosomal RNA as a loading control. (B) Immunoblot of root protein extracts from wild-type and 35S-LRX1 plants (1) and wild-type and 35S-N/LRX1 plants (2). The membrane was immunoreacted with anti-LRX1 antiserum. The endogenous LRX1 protein was not detectable with these antibodies. A duplicate gel was stained with Coomassie blue as loading control (right). (C) Phenotype of the lines used in A and B. 35S-LRX1 plants (2) are indistinguishable from wild-type plants (1), whereas 35S-N/LRX1 plants (3) show the same phenotype as lrx1 mutants (4). Bar, 350 μm.

To study the role of the LRR domain, transgenic plants were generated that expressed under the control of the 35S CaMV promoter, a modified LRX1 protein whose extensin domain had been deleted (35S-N/LRX1). Protein immunoblotting revealed high expression of a 45-kD polypeptide in 15 of 18 transgenic lines (data not shown). The size of the detected protein is in good agreement with the calculated mass of the truncated LRX1 protein (35 kD). All of the lines expressing the N/LRX1 protein displayed a strong defect in root hair development, which completely reproduced the lrx1 mutant phenotype (Fig. 7C, panel 3). No other alteration in development was observed in these transgenics. One representative homozygous transgenic line harboring a single T-DNA insertion and showing a high N/LRX1 expression was further characterized by Western and Northern analysis (Fig. 7A, B, panel 2). Northern hybridization showed that the endogenous LRX1 expression was not reduced in 35S-N/LRX1 plants (Fig. 7A, panel 2). Hence, the observed phenotype is not caused by silencing of the endogenous LRX1 gene, but is the result of a dominant-negative effect due to the overexpression of the truncated LRX1 protein.

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the function of LRX1, a new Arabidopsis gene encoding an extracellular protein sharing homology with extensins and LRR proteins. Analysis of three lrx1 null mutants revealed that LRX1 is an important component in the regulation of root hair morphogenesis. The absence of LRX1 causes specific root hair defects such as abortion, swelling, and branching. Moreover, LRX1 expression is completely associated with root hair development because seedlings that are inhibited in this process, either as the result of a mutation (i.e., the rhd6 mutant) or treatment with AVG, did not show LRX1 expression. By use of plants producing a c-myc-tagged LRX1, the protein could be localized in the root hair proper throughout all stages of root hair development. The whole-mount immunolocalization of mycLRX1 very likely reflects the exact localization of the endogenous LRX1 protein because the recombinant protein was able to fully complement the lrx1 mutation. The absence of labeling in the epidermal part of trichoblast cells is consistent with the observation that in lrx1 mutants these cells are normal except for the altered hair development.

LRR/extensins form a sub-family of LRR proteins

LRX1 encodes an amino-terminal domain that matches the consensus sequence of plant extracellular LRRs (Jones and Jones 1997). The latter form the ligand-binding domain of receptor-like kinases such as CLAVATA1 (Clark et al. 1997), a protein thought to activate a signaling cascade on interaction with the secreted peptide CLAVATA3 (Trotochaud et al. 2000). LRRs can also directly regulate enzyme activity, as found for polygalacturonase-inhibiting proteins (Toubart et al. 1992). However, the LRR domain of LRX1 shows only a relatively low identity with either LRR–RLKs or PGIPs. Thus, the comparable number of LRRs found in LRX1 (11) and PGIPs (10) is unlikely to reflect a common inhibitory activity. In contrast, the LRR domain of LRX1 shows a high similarity (53% and 73% of identity, respectively) with the LRR domain of the maize PEX1 (Rubinstein et al. 1995a) and the tomato TOML-4 (Zhou et al. 1992; Jones and Jones 1997), which are both LRR/extensin proteins. This suggests that LRR/extensins constitute a new sub-family of LRR proteins, which is conserved among distantly related taxa. Interestingly, PEX1 has been localized in the walls of growing pollen tubes, a cell type which, like root hairs, elongates by tip growth (Rubinstein et al. 1995b). Therefore, involvement in tip growth might be a general feature of LRX1-like proteins. However, it is possible that among the 11 members comprising the large LRX family in Arabidopsis, some are required for different cell wall-related processes.

The extensin domain is required for insolubilization of LRX1 in the cell wall and is crucial for LRX1 function

As extensins are frequently insolubilized in the cell wall upon developmental cues or stress (Showalter 1993), it is possible that the function of the extensin domain of LRX1 is to direct the protein to a particular domain within the cell wall and/or to insolubilize it. The immunodetection of mycLRX1 in planta and in purified cell wall fractions provides strong evidence of the immobilization of LRX1 in the cell wall, possibly through oxidative cross-linking (Fry 1986; Brady and Fry 1997) at the nine Tyr-x-Tyr sites present in the extensin domain. The even distribution of LRX1 along the root hair proper is a possible consequence of the protein insolubilization and LRX1 might actually be translocated to the cell wall and exert its function only at the tip of the growing root hair. During ongoing growth, the cell wall at the tip becomes a part of the lateral wall, resulting in the observed distribution of LRX1. Moreover, our results suggest that the extensin domain is required for the correct LRX1 function. Overexpression of an LRX1 protein deprived of its extensin domain (N/LRX1) phenocopies the lrx1 mutants, whereas the overexpression of the full-length LRX1, although expressed at a level similar to N/LRX1, does not result in an altered root hair development. This suggests that the absence of the extensin domain allows N/LRX1 to compete for and block the interaction sites used by the endogenous LRX1 protein. In contrast, the overexpressed full-length LRX1 protein containing the extensin domain merely substitutes for the endogenous protein, as shown by complementation of the lrx1 mutant.

The possible role of LRX1 in cell expansion

Because root hair expansion is restricted to the tip, cell morphology largely depends on the proper regulation of the cellular events occurring at that location. The lrx1 root hair phenotype might thus be explained by a defective cell expansion, resulting from a spatially deregulated exocytosis or altered deposition of new cell wall material. In this perspective, LRX1 might contribute to establish or stabilize root hair polarization and tip growth by physically connecting the cell wall and the plasma membrane. The importance of such interactions in cell polarization was suggested by the observation that in Fucus embryos the cell wall is necessary to fix the polarization axis that determines the rhizoid outgrowth (Kropf et al. 1988; Fowler and Quatrano 1997). Because root hair polarization and growth orientation depend on both the microtubules (MTs) and the [Ca2+] gradient at the tip (Bibikova et al. 1997, 1999; Wymer et al. 1997), the root hair defects observed in the lrx1 mutants identify MTs and membrane Ca2+ channels as possible direct or indirect targets for LRX1 action. Alternatively, LRX1 could function in the regulation and organization of cell wall expansion at the tip of root hairs, either by recruiting enzymes into critical domains of the cell wall or by directly regulating their activity. Defective regulation of the cell wall assembly might disturb tip growth and result in deformed root hairs. The morphological defects of rhd4 root hairs that are in some extent similar to those observed in lrx1 mutants, were shown to be associated with an irregular thickness of the cell wall, possibly as a consequence of a disturbed wall expansion (Galway et al. 1999). Moreover, the recent identification of KOJAK as a cellulose synthase-like enzyme shows that cell wall alteration can lead to root hair abortion by the rupture of the wall (Favery et al. 2001).

In summary, we have characterized LRX1 as a member of a new family of extracellular LRR/extensin proteins. LRX1 is one of the very few identified proteins that act in plant cell morphogenesis and shape determination. It constitutes a novel candidate for the regulation of cell wall expansion. Experiments are currently underway to characterize putative interacting partners of LRX1 and to genetically dissect the pathway it is involved in. Furthermore, using the complementation of the lrx1 mutant phenotype as a parameter for protein function, we have an excellent tool to investigate in detail the different parts of the LRX1 extensin moiety, which appears to be important for the function of the protein both in regard to insolubilization and targeting to the correct cell wall domain.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia was used for all experiments. The rhd1, rhd2, rhd3, and rhd4 mutants were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. rhd6 and tip1 were a gift of J. Schiefelbein and cow1-2 was provided by C. Grierson. The lrx1 mutants were isolated from an En-1 mutagenized Arabidopsis population (Wisman et al. 1998) by PCR screening as reported in Baumann et al. (1998) by use of the LRX1 gene specific primers MUT1f, MUT1r, MUT2f, MUT2r, and a probe derived from the LRX1 cDNA fragment 332–1148 spanning the LRR domain (referred to as LRX1 probe). The precise positions of the En-1 insertions were obtained by cloning and sequencing the PCR products spanning the right and left border of the En-1 element. Mutant plants were backcrossed at least four times with wild-type plants to remove additional insertions.

Plants were grown in soil, under continuous light at 24°C in growth chambers. Alternatively, seeds were surface sterilized, stratified in darkness for 2–3 d at 4°C, and grown vertically at 24°C, under continuous illumination along the surface of half-strength MS medium, supplemented with 2% sucrose and 0.6% Phytagel (Sigma). Transgenic seedlings were selected on half-strength MS plates with 0.8% Phytoagar (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycine. All analyses using transgenic lines were performed in the T3 or T4 generation.

DNA primers

The following DNA primers were used for plasmid constructs, probe amplification, and screening of the En-1-mutagenized population. The numbers in parentheses refer to the position of the 5′ end of the primer relative to the transcription start of LRX1. lrx1f, 5′-AGTCGTTGCTGGCATTGACC-3′ (332); lrx1r, 5′-ATCCACAGGGCGAGCAAGC-3′ (1148); pGUSf, 5′-TAT GAACTTACCATTCCAAGC-3′ (-1562); pGUSr, 5′-GAAGAT CTAGAGGGAACGAAGAGGAGGGA-3′ (71); MUT1f, 5′-GACCACGACGATGAAAGCGACTTTTGG-3′ (114); MUT2f, 5′-AGATCGGAAACCTCAAGAAAGTGACG-3′ (817); MUT1r, 5′-AGCTCGAACGCTAGGTGACATCTTGG-3′ (1700); MUT2r, 5′-CATATGAGACGCTTGGCATCGGTGG-3′ (2235); MYCf, 5′-CCCCCCCGAGGTCGACGGTATC-3′; MYCr, 5′-ATCCC TCGGGATCGATTTCGAACC-3′; 35SLRX1f, 5′-TAAAATGA ATTCTCTTGACCCATAAGC-3′ (8); 35SLRX1r, 5′-AAAGTT CTAGATTGTGAGTAGTCTCG-3′ (2337); 35SN/LRX1r, 5′-CAAAGATCTAGACTGTTTATCCGATC-3′ (1130); recLRRf, 5′-CTGCATGCTACCCGAAAACCCGAGTCG-3′ (310); and recLRRr, 5′-AGCTGCAGCCGGTGATGCAGTTCATGG-3′ (1097).

LRX1 genomic clone isolation and RACE–PCR

An EMBL3 Arabidopsis thaliana genomic library (Clontech) was screened with the 32P-labeled LRX1 probe. A SphI–NcoI genomic fragment containing the LRX1 gene with 1.8 kb of 5′- and 0.83 kb of 3′-untranslated sequence was isolated, cloned, and sequenced to confirm its identity (referred to as pλLRX1). The actual transcription start site of the LRX1 gene, the polyadenylation signal, and the cDNA sequence were determined by 5′- and 3′- RACE–PCR by use of the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen) and the gene-specific primers MUT1r and MUT2f. The resulting PCR products were cloned and sequenced (eight independent clones for each PCR product). The LRX1 cDNA sequence has been deposited with GenBank under accession number AY026364.

Constructs and plant transformation

For the LRX1 promoter∷GUS fusion construct (pLRX1∷GUS), 1.6 kb of the promoter region was amplified by PCR from pλLRX1 with the primers pGUSf and pGUSr, digested with XbaI and HindIII, and cloned into pGPTV-KAN (Becker 1992). For expression of the c-myc-tagged LRX1 protein (mycLRX1 construct), a sixfold duplicated copy of the human c-myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL) sequence was amplified by PCR from the vector CD3–128 (Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center) by use of the primers MYCf and MYCr, digested with AvaI, and ligated into the single AvaI restriction site of pλLRX1 (position 329 in the LRX1 cDNA). A clone with the c-myc tag in the sense orientation was selected, linearized with NotI, and subcloned into pART27 (Gleave 1992). For constitutive expression of the full-length (35S–LRX1) and truncated (35S–N/LRX1) LRX1 proteins, the LRX1 coding sequences were amplified by PCR from pλLRX1 with the primer combinations 35SLRX1f/35SLRX1r and 35SLRX1f/35SN/LRX1r, digested with EcoRI and XbaI, and cloned into pART7. The expression cassette of pART7 was then subcloned into the binary vector pART27 (Gleave 1992).

The T-DNA constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and plant transformation was performed following the floral dip method described by Clough and Bent (1998). Transgenic plants were selected on MS agar plates containing kanamycine and the number of segregating T-DNA loci was assessed by segregation of the kanamycine resistance in the next generation. Resistant plants were transferred to soil and selected to obtain T3 homozygous seeds.

GUS histochemical analysis

Histochemical staining for GUS activity was performed by incubation in 50 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide (X-gluc), in 50 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, at 37°C for 16 h. For AVG treatments, plants were grown on the surface of normal MS medium for 3 d, transferred onto MS plates supplemented with 20 mM L-α-(2-amino-ethoxyvinyl)glycine (Sigma) and grown for 5 additional days before histochemical staining or Northern analysis. As control, plants were transferred onto MS plates without AVG and subsequently grown for 5 d.

Protein immunoblotting

Plant material was ground in liquid nitrogen and proteins were extracted on ice with 0.5 M CaCl2 in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, and proteinase inhibitors (Complete mini, Boehringer-Mannheim). Proteins were precipitated with deoxycholic acid/tricarboxylic acid and resuspended in Laemmli buffer. Alternatively, proteins were directly extracted in Laemmli buffer at 100°C for 5 min (35S–N/LRX1 extract). Proteins were resolved by 6% to 8% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) with the Mini Trans-Blot transfer cell (BioRad). Transfer was performed at 10 mA, for 16 h at 4°C, in 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 15% (vol/vol) methanol. Alternatively (35S–N/LRX1 extract), transfer was done in the Trans-Blot SD semi-dry transfer cell (BioRad), in 0.0375% (wt/vol) SDS, 48 mM Tris, 39 mM glycine, 20% (vol/vol) methanol at 0.8 mA/cm2 of membrane for 30 min. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween-20 (TBS-T) with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk. Primary antiserum dilutions were as follows: rabbit anti-LRX1 IgG, 1:10,000; mouse anti-c-myc 9E10.2, 1:5000 (Abcam). Secondary antiserum dilutions were as follows: goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG, 1:5000 (BioRad); goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG, 1:20,000 (Sigma). All antibodies were diluted in TBS-T, incubations were done at room temperature for 1 h and were followed by four washes of 15 min in TBS-T. Chemiluminescence detection was performed with ECL+ reagents according to the manufacturer recommendations (Amersham).

Tissue print, whole-mount, and cell wall immunolocalization

Tissue-print experiments were performed as described by Cassab (1992). Immunodetection was performed with mouse anti-c-myc 9E10.2, 1:500 (Abcam) and rabbit anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies, 1:1000 (Boehringer Mannheim) followed by detection using the alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate of BioRad.

Whole-mount immunolocalizations were done with 3-d-old seedlings, which were fixed for 30 min at room temperature in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), rinsed four times in HEPES buffer, and 6 h in 2% (wt/vol) BSA, 4× SSC. Incubations with antisera diluted in 4× SSC, 2% (wt/vol) BSA were performed at 4°C for 16 h [primary antibodies, mouse anti-c-myc 9E10.2, 1:1000 (Abcam); secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse 1 nm of gold-conjugate IgG, 1:1000 (British BioCell International)], and followed by four washes of 1 h each in 4× SSC, 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween-20. Finally, samples were rinsed four times in ultra-pure water for 15 min each, and the signal was amplified with silver enhancement reagents (British BioCell International). Observations were made with a Leitz Laborlux microscope equipped with epipolarized illumination.

Cell wall preparations were obtained by grinding fresh root material from 14-d-old seedlings in liquid nitrogen followed by extraction in phenol:acetic acid according to Fry (1988). The purified cell walls were resuspended in 80% acetone and laid down on Biobond-coated microscope slides (British BioCell International). Immunodetection was then performed on the slides as follows: material was blocked for 2 h in TBS-T, 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (British BioCell International), 5% (wt/vol) BSA. Incubations with antisera diluted in TBS-T, 1% (vol/vol) normal goat serum, 1% (wt/vol) BSA, were done for 2 h at room temperature [primary antibody, mouse anti-c-myc 9E10.2, 1:200 (Abcam); secondary antibody,: goat anti-mouse 1 nm of gold-conjugate IgG, 1:250 (British BioCell International)] and followed by three washes of 10 min each in TBS-T. Three additional washes of 3 min in pure water were performed before amplification of the signal with silver enhancement reagents (British BioCell International).

Phenotype observations

Light microscopical observations were done with a Leica stereomicroscope LZ M125. For scanning electron microscopy, seedlings grown on the surface of MS medium were transferred onto humid nitrocellulose membranes on metal stabs and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were partly freeze dried in high vacuum (<2 × 10−4 Pa) at −90°C for 30 min and sputter coated with platinum in a preparation chamber SCU 020 (BAL-TEC) before observation at −120°C in a SEM 515 scanning electron microscope (Philips).

Production of polyclonal antibodies

The sequence encoding the LRR domain of LRX1 was amplified by PCR using the primers recLRRf and recLRRr. Purified PCR products were digested with SphI and PstI, cloned into pQE-30 (Qiagen), and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21. Single colonies were selected and grown to an OD600 of 0.6 before induction with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, lysed in 5 vol of 8 M urea, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.01 M Tris (pH 8), for 2 h at room temperature, and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (30 min, 10,000g). The His6x–recLRR fusion protein was recovered and purified by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose bead column (Qiagen). Two rabbits were immunized with the purified His6x–recLRR protein, IgG were purified by protein A affinity chromatography and used for immunoblotting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Beat Frey and Urs Jauch for technical assistance with SEM; Dr Ellen Wisman and the MPIZ, Köln for the access to the En-1 mutagenized Arabidopsis collection; Drs. John Schiefelbein and Claire Grierson for kindly providing the seeds of rhd6, tip1, and cow1 mutants; the ABRC for the rhd1, rhd2, rhd3, and rdh4 mutants as well as the CD3–128 plasmid; Drs. Catherine Feuillet and Eric van der Graaff for helpful discussions and careful reading of the manuscript and Dr. Nikolaus Amrhein for his continuous support. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31–51055.97) and the University of Zürich.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

While this work was in press, TRHJ, a new gene encoding a potassium transporter important for root hair development was cloned by Rigas et al. (2001).

Footnotes

E-MAIL bkeller@botinst.unizh.ch; FAX 41-1-6348204.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.200201.

References

- Baumann E, Lewald J, Saedler H, Schulz B, Wisman E. Successful PCR-based reverse genetic screens using an En-1–mutagenised Arabidopsis thaliana population generated via single-seed descent. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Kemper E, Schell J, Masterson R. New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:1195–1197. doi: 10.1007/BF00028908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova TN, Zhigilei A, Gilroy S. Root hair growth in Arabidopsis thaliana is directed by calcium and an endogenous polarity. Planta. 1997;203:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s004250050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova TN, Blancaflor EB, Gilroy S. Microtubules regulate tip growth and orientation in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999;17:657–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DJ, Kjellbom P, Lamb CJ. Elicitor- and wound-induced oxidative cross-linking of a proline-rich plant cell wall protein: A novel, rapid defense response. Cell. 1992;70:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90530-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JD, Fry SC. Formation of di-isodityrosine and loss of isodityrosine in the cell walls of tomato cell-suspension cultures treated with fungal elicitors or H2O2. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:87–92. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: Consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassab GI. Localization of cell wall proteins. In: Reid PD, Pont-Lezica RF, editors. Tissue printing. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- ————— Plant cell wall proteins. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1998;49:281–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1997;89:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Enzymes and other agents that enhance cell wall extensibility. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1999;50:391–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer DP. Cellulose synthase: Exciting times for a difficult field of study. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1999;50:245–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L, Duckett C, Grierson C, Linstead P, Schneider K, Lawson E, Dean C, Poethig S, Roberts K. Clonal relationships and cell patterning in the root epidermis of Arabidopsis. Development. 1994;120:2465–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Favery B, Ryan E, Foreman J, Linstead P, Boudonck K, Steer M, Shaw P, Dolan L. KOJAK encodes a cellulose synthase-like protein required for root hair cell morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:79–89. doi: 10.1101/gad.188801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JE, Quatrano RS. Plant cell morphogenesis: Plasma membrane interactions with the cytoskeleton and cell wall. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. Isodityrosine, a new cross-linking amino acid from plant cell wall glycoprotein. Biochem J. 1982;204:449–455. doi: 10.1042/bj2040449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cross-linking of matrix polymers in the growing cell walls of angiosperms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:165–186. [Google Scholar]

- ————— . The growing plant cell wall: Chemical and metabolic analysis. Harlow, UK: Longman Scientific & Technical; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Galway ME, Heckman JW, Schiefelbein JW. Growth and ultrastructure of Arabidopsis root hairs: The rhd3 mutation alters vacuole enlargement and tip growth. Planta. 1997;201:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01007706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galway ME, Lane DC, Schiefelbein JW. Defective control of growth rate and cell diameter in tip growing root hairs of the rhd4 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Can J Bot. 1999;77:494–507. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Muniz N, Martinez-Izquierdo JA, Puigdomenech P. Induction of mRNA accumulation corresponding to a gene encoding a cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein by fungal elicitors. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:623–632. doi: 10.1023/a:1006056000957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleave AP. A versatile binary vector system with a T-DNA organizational structure conducive to efficient integration of cloned DNA into the plant genome. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:1203–1207. doi: 10.1007/BF00028910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson CS, Roberts K, Feldmann KA, Dolan L. The COW1 locus of Arabidopsis acts after RHD2, and in parallel with RHD3 and TIP1, to determine the shape, rate of elongation, and number of root hairs produced from each site of hair formation. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:981–990. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinn TL, Stone JM, Walker JC. HAESA, an Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase, controls floral organ abscission. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:108–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Jones JDG. The role of leucine-rich repeat proteins in plant defenses. Adv Bot Res. 1997;24:89–167. [Google Scholar]

- Keller B. Structural cell wall proteins. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1127–1130. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller B, Lamb CJ. Specific expression of a novel cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein gene in lateral root initiation. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:1639–1646. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski MJ, Lamport DT. Extensin: Repetitive motifs, functional sites, post-translational codes, and phylogeny. Plant J. 1994;5:157–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.05020157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox JP. The extracellular matrix in higher plants: Developmentally regulated proteoglycans and glycoproteins of the plant cell surface. FASEB J. 1995;9:1004–1012. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7544308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Deisenhofer J. The leucine-rich repeat: A versatile binding motif. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf D, Kloareg B, Quatrano R. Cell wall is required for fixation of the embryonic axis in Fucus zygotes. Science. 1988;239:187–190. doi: 10.1126/science.3336780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci J, Schiefelbein J. The rhd6 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana alters root hair initiation through an auxin-associated and ethylene-associated process. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1335–1346. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DD, de Ruijter NCA, Bisseling T, Emons AMC. The role of actin in root hair morphogenesis: Studies with lipochito-oligosaccharide as a growth stimulator and cytochalasin as an actin perturbing drug. Plant J. 1999;17:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol F, Höfte H. Plant cell expansion: Scaling the wall. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:12–17. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Cavell AC, Dolan L, Roberts K, Grierson CS. Genetic interactions during root hair morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1961–1974. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigas S, Debrosses G, Haralampidis K, Vicente-Agullo F, Feldmann KA, Grabov A, Dolan L, Hatzopoulos P. THR1 encodes a potassium transporter required for tip growth in Arabidopsis root hairs. Plant Cell. 2001;13:139–151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein AL, Broadwater AH, Lowrey KB, Bedinger PA. Pex1, a pollen-specific gene with an extensin-like domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995a;92:3086–3090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein AL, Marquez J, Suarez Cervera M, Bedinger PA. Extensin-like glycoproteins in the maize pollen tube wall. Plant Cell. 1995b;7:2211–2225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein J, Somerville C. Genetic control of root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 1990;2:235–243. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein J, Shipley A, Rowse P. Calcium influx at the tip of growing root hair cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1992;187:455–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00199963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein J, Galway M, Masucci J, Ford S. Pollen tube and root hair tip growth is disrupted in a mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:979–985. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein JW. Constructing a plant cell. The genetic control of root hair development. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1525–1531. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirsat AH, Bell A, Spence J, Harris JN. The Brassica napus extA extensin gene is expressed in regions of the plant subject to tensile stresses. Planta. 1996;199:618–624. [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell. 1993;5:9–23. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WY, Wang GL, Chen LL, Kim HS, Pi LY, Holsten T, Gardner J, Wang B, Zhai WX, Zhu LH, et al. A receptor kinase-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, Xa21. Science. 1995;270:1804–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto M, Roberts K, Dolan L. Ethylene is a positive regulator of root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1995;8:943–948. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8060943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii KU, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Matsuura Y, Yokoyama R, Whittier RF, Komeda Y. The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell. 1996;8:735–746. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toubart P, Desiderio A, Salvi G, Cervone F, Daroda L, De Lorenzo G. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding the endopolygalacturonase-inhibiting protein (PGIP) of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plant J. 1992;2:367–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1992.t01-35-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud AE, Jeong S, Clark SE. CLAVATA3, a multimeric ligand for the CLAVATA1 receptor-kinase. Science. 2000;289:613–617. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Lockwood SK, Hoeltzel MF, Schiefelbein JW. The ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE3 gene encodes an evolutionarily conserved protein with GTP-binding motifs and is required for regulated cell enlargement in Arabidopsis. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:799–811. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LG, Fry JC. Extensin: A major cell wall glycoprotein. Plant Cell Environ. 1986;9:239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Wisman E, Cardon GH, Fransz P, Saedler H. The behaviour of the autonomous maize transposable element En/Spm in Arabidopsis thaliana allows efficient mutagenesis. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:989–999. doi: 10.1023/a:1006082009151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wycoff KL, Powell PA, Gonzales RA, Corbin DR, Lamb C, Dixon RA. Stress activation of a bean hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein promoter is superimposed on a pattern of tissue-specific developmental expression. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:41–52. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymer CL, Bibikova TN, Gilroy S. Cytoplasmic free calcium distributions during the development of root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1997;12:427–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12020427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Rumeau D, Showalter AM. Isolation and characterization of two wound-regulated tomato extensin genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:5–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00029144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]