Abstract

The plant pathogen Dickeya chrysanthemi EC16 (formerly known as Petrobacterium chrysanthemi EC16 and Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16) was found to produce a new triscatecholamide siderophore, cyclic trichrysobactin, the related catecholamide compounds, linear trichrysobactin, and dichrysobactin, as well as the previously reported monomeric siderophore unit, chrysobactin. Chrysobactin is comprised of L-serine, D-lysine and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA). Trichrysobactin is a cyclic trimer of chrysobactin joined by a triserine lactone backbone. The chirality of the ferric complex of cyclic trichrysobactin is found to be in the Λ configuration, similar to Fe(III)-bacillibactin, which contains a glycine spacer between the DHBA and L-threonine components and opposite that of Fe(III)-enterobactin, which contains DHBA ligated directly to L-serine.

Nearly all bacteria require iron for growth. The insolubility of ferric hydroxide in aerobic conditions at neutral pH (Fe(OH)3, Ksp = 10−39) however, severely limits the amount of available iron(III) in solution. Bacteria have therefore evolved multiple pathways of iron acquisition in order to obtain this essential nutrient. In response to low iron environments, bacteria produce and secrete siderophores, low-molecular weight organic compounds which bind iron(III) with high affinity, capturing iron(III) from the surrounding environment and delivering it to the cells. Several hundred structures of bacterial siderophores are known, most of which are comprised of a mixture of functional groups which coordinate Fe(III), commonly catechols, hydroxamic acids, and α-hydroxycarboxylic acids.

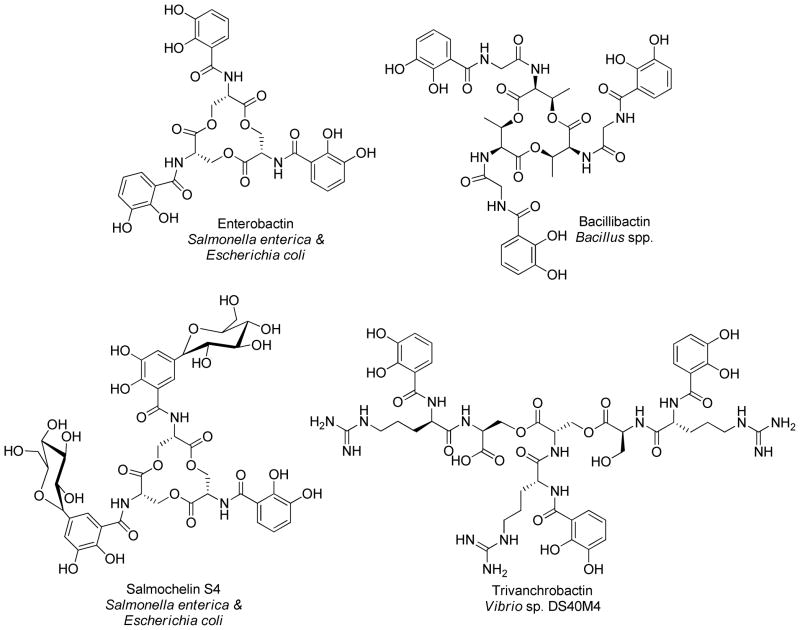

The triscatecholate siderophores, enterobactin and bacillibactin, stand out for their exceptionally high affinity for Fe(III) (Fe-ent3− Kf = 1049, Fe-bb3−, Kf = 1047.6).1, 2 Enterobactin, produced by many different Gram negative enteric and pathogenic bacteria, and bacillibactin, produced by Gram positive, Bacillus spp., both coordinate iron(III) through three 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid units that are appended to a cyclic trilactone scaffold of either L-serine (enterobactin) or L-threonine (bacillibactin) (Figure 1).3–5 Additionally, bacillibactin incorporates a glycine spacer between the L-threonine and DHBA units.5 Until recently, enterobactin and bacillibactin along with the salmochelins (glucosylated derivatives of enterobactin, isolated from Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic E. coli)6 (Figure 1) were the only known triscatecholate siderophores. In addition, a new siderophore biosynthetic route was identified in Streptomyces griseus for the production of griseobactin, which is predicted to be a cyclic trimeric ester of 2,3-dihydroxy-benzyol-arginyl-threonine.7 Recently, we reported the isolation and structure characterization of trivanchrobactin, a new linear triscatecholate siderophore which differs from enterobactin by incorporating an arginine spacer between each DHBA and serine (Figure 1).8 Originally the monomer unit, vanchrobactin, was reported as the siderophore produced by Vibrio anguillarum serotype O2.9 Chrysobactin is a related monocatecholate siderophore comprised of L-serine, D-lysine, and DHBA, and produced by the plant pathogen Dickeya dadantii 3937 (formerly known as Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 and Pectobacterium chrysanthemi 3937).10 On the basis that both vanchrobactin and trivanchrobactin siderophores have been reported, and given the structural similarities of vanchrobactin and chrysobactin, we hypothesized that some bacteria may also synthesize a chrysobactin trimer as the dominant siderophore.

Figure 1.

Triscatecholate siderophores.

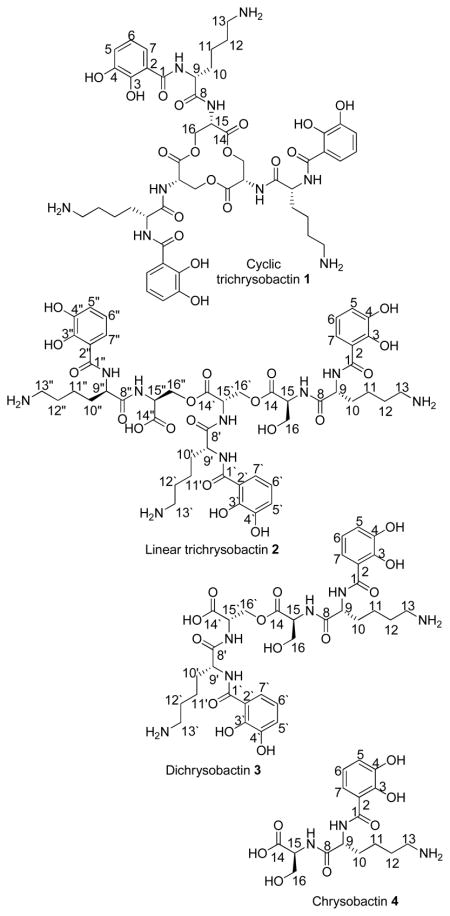

Herein we report the isolation and structure determination of a new triscatecholamide tri-serine lactone siderophore, cyclic trichrysobactin (1), produced by the plant pathogen Dickeya chrysanthemi EC16. Additionally, three related compounds, a linear trichrysobactin (2), dichrysobactin (3), and the known siderophore chrysobactin (4) (α-N-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-D-lysyl-L-serine)10, a monomer unit of trichrysobactin, were isolated and characterized.

Results and Discussion

Siderophores produced by D. chrysanthemi EC16 were isolated from the cell-free culture supernatant by adsorption to Amberlite XAD-2 resin. The siderophores were eluted in MeOH and further purified by preparative scale RP-HPLC. Four compounds that reacted with the Fe(III)-chrome azurol sulfonate (CAS) complex, consistent with the presence of putative apo-siderophores, were purified by RP-HPLC (Supporting Information Figure S1).11 The molecular formula of 1 was established as C48H63N9O18 by HRESIMS; the molecular formula of 2 as C48H65N9O19; the molecular formula of 3 as C32H44N6O13; and the molecular formula of 4 as C16H24N3O7. The molecular weight of 4 was consistent with that of the known siderophore chrysobactin.10 The structure of chrysobactin 4 was further confirmed by NMR analysis (Table 2, Supporting Information Figures S10–S13).

Table 2.

NMR Data for Chrysobactins 1 and 4 (800 MHz for 1H; 200 MHz for 13C) in CD3OD

| Position | Cyclic Trichrysobactin (1)

|

Chrysobactin (4)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH (J inHz) | COSY | HMBC | δC | δH (J in Hz) | |

| DHBA | ||||||

| 1 | 170.1, C | 170.8, C | ||||

| 2 | 117.8, C | 117.4, C | ||||

| 3 | 148.9, C | 149.4, C | ||||

| 4 | 147.1, C | 147.2, C | ||||

| 5 | 119.8, CH | 6.98, dd (8.1,1.6) | 6 | 2,3,4,5 | 119.8, CH | 6.98, dd (8.0, 1.6) |

| 6 | 120.09, CH | 6.77, t (8.0) | 5,7 | 1,2,3,4,5 | 119.9, CH | 6.78, t (8.0) |

| 7 | 120.08, CH | 7.36, dd (8.0,0.8) | 6 | 1,3,4,5 | 119.7, CH | 7.35, dd (8.0, 0.8) |

| Lysine | ||||||

| 8 | 174.4, C | 174.0, C | ||||

| 9 | 54.6, CH | 4.67, m | 10,10 | 1,8,10,11 | 56.2, CH | 4.76, dd (8.8, 5.6) |

| 10 | 32.5, CH2 | 1.96, m | 9,10,11 | 8,9,10,11 | 32.7, CH2 | 2.04, m |

| 1.80, m | 9,10,11 | 8,9,10,11 | 1.89, m | |||

| 11 | 23.8, CH2 | 1.49, m | 10,11,12 | 9,10,12,13 | 23.7, CH2 | 1.55, m |

| 1.42, m | 10,11,12 | 9,10,12,13 | ||||

| 12 | 28.2, CH2 | 1.67, m | 13,11 | 10,11,13 | 28.1, CH2 | 1.74, m |

| 13 | 40.5, CH2 | 2.90, t (6.4) | 12 | 11,12 | 40.5, CH2 | 2.96, m |

| Serine | ||||||

| 14 | 170.6, C | 173.1, C | ||||

| 15 | 53.8, CH | 4.80, t (4.0) | 16,16 | 8,14,16 | 54.3, CH | 4.53, t (4.0) |

| 16 | 65.8, CH2 | 4.66, m | 15,16 | 14,15 | 62.7, CH2 | 3.96, dd (11.2, 4.8) |

| 4.43, dd (11.2, 4.8) | 15,16 | 14,15 | 3.87, dd (11.2, 4.0) | |||

The parent ion mass (m/z 1054.44 [M+H]+) and fragmentation pattern observed in the tandem mass spectrum (ESI-MS/MS) of 1 suggest a cyclic trimer of chrysobactin joined by three serine ester bonds (Figure 2). The ESI-MS/MS of 1 shows two major daughter ions (m/z 790.32 and 265.12) corresponding to fragmentation releasing a dihydroxybenzoyl (DHB)-Lys unit, from 1. Fragment ions m/z 703.30 and 352.16, corresponding to the [M+H]+ of two-thirds and one-third of 1, result from fragmentation at two serine ester bonds. Other fragments which arise from subsequent loss of DHB, lysine and serine units from the intact cyclic trimer 1 are also observed (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ESI-MS/MS of 1. The circled region corresponds to 1/3 of 1, m/z 352.16 [M+H]+ and the remaining 2/3 of 1, m/z 703.30 [M+H]+ is outlined by a dotted line.

Table 1.

Molecular Ions and Common Mass Fragments of 1–4.

| Cyclic Trichrysobactin (1) [M+H]+ | Linear Trichrysobactin (2) [M+H]+ | Dichrysobactin (3) [M+H]+ | Chrysobactin (4) [M+H]+ | Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1054.44 | 1072.50 | 721.32 | 370.17 | Parent Ion |

| 918.42 | 936.46 | Loss of DHB* | ||

| 790.32 | 808.35 | Loss of Lys* | ||

| 703.30 | 721.32 | Loss of Ser* | ||

| 567.27 | 585.28 | 585.28 | Loss of DHB* | |

| 439.20 | 457.20 | 457.21 | Loss of Lys* | |

| 352.16 | 370.17 | 370.17 | Loss of Ser* | |

| 265.12 | 265.13 | 265.13 | 265.12 | DHB-Lys* |

| 234.13 | 234.15 | Lys-Ser* | ||

| 137.03 | DHB* | |||

| 129.11 | 129.11 | 129.11 | 129.11 | Lys* |

Relative to the ion listed immediately above in the column. For simplicity, certain ESI/MSMS fragments are not listed in this table because they are not common for all compounds 1–4.

ESI-MS/MS analysis of 2 suggests a linear trimer, composed of three chrysobactin units linked by two serine ester bonds. The parent ion m/z 1072.50 [M+H]+, and major fragment ions of 2 are 18 mass units higher than that of 1, consistent with the presence of free terminal serine hydroxy and carboxylic acid groups in 2 (Table 1, Figure S2). ESI-MS/MS analysis of 3 suggests a dimer of chrysobactin linked by one serine ester bond. The parent ion at m/z 721.32 [M+H]+ is observed, along with two major fragment ions m/z 457.21 and 265.13 corresponding to (Ser)2-Lys-DHB and DHB-Lys residues resulting from fragmentation at one Lys-Ser amide bond of 3. Fragments m/z 370.17 and 352.15, arising from fragmentation at the serine ester bond, are also observed (Table 1, Figure S3). ESI-MS/MS of 4, m/z 370.17 [M+H]+, shows major fragments m/z 265.12, 234.15, 137.03, and 129.11 resulting from loss of Ser, loss of DHB, loss of Ser-Lys, and loss of DHB-Ser from 4 (Table 1, Figure S4). ESI-MS/MS fragments of 1–4 are summarized in Table 1. Amino acid analysis by Marfey’s method12 established the presence of D-lysine and L-serine in each of compounds 1–4.

The 1H and 13C NMR assignments for 1 were confirmed by two dimensional 1H-1H COSY, HSQC and HMBC experiments (Table 2, and Supporting Information Figures S5-S9). The aromatic splitting patterns in the 1H NMR spectra of 1–4 are indicative of a 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl moiety (DHBA). Cyclic trichrysobactin 1 is a symmetrical molecule and therefore the NMR data for 1 closely resembles that of the monomer chrysobactin 4 (Table 2, and Supporting Information Figures S10–S13). The 13C NMR spectrum of 1 has 16 distinct carbon resonances corresponding to three carbonyl carbons (δ 170.1 to 174.4), five methylene carbons (δ 23.8 to 40.5 for lysine and δ 65.8 for serine), two methine carbons (δ 54.6 for lysine and δ 53.8 for serine) and six aromatic carbon resonances (δ 117.8–148.9). The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 shows 13 distinct resonances corresponding to three aromatic protons (δ 6.8–7.4), 10 methylene protons (δ 1.4–2.9 for lysine and δ 4.4, 4.7 for serine), and two methine protons (δ 4.67 for lysine and δ 4.80 for serine). The HMBC correlation between the lysine α-proton (δ 4.67) and the carbonyl carbon of the DHBA moiety (δ 170.1) indicates that DHBA is attached to the N-terminus of lysine. Furthermore, the HMBC correlation between the serine α-proton (δ 4.80) and the lysine carbonyl carbon (δ 174.4) establishes the lysine-serine linkage. Additional long range HMBC correlations confirm the connectivity of DHBA and amino acid residues in 1 (Table 2).

The key feature in the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 which distinguishes it from 4 is the downfield shift of the serine methylene protons of 1 (δ 4.43 and δ 4.66) compared to the serine methylene protons of 4 (δ 3.96 and δ 3.87), consistent with the presence of a neighboring ester group in 1, versus a free serine hydroxy group in 4. The serine methine proton of 1 (δ 4.80) is also shifted downfield compared to that of 4 (δ 4.53), but to a lesser degree.

The structures of 2 and 3 were inferred from mass spectrometry, 1H and 13C NMR, and amino acid analysis (Supporting Information Table S1 and Figures S14-S17). The presence of two serine ester linkages in 2 and one serine ester linkage in 3 was established by comparison of the proton integration as well as the chemical shifts of the serine methylene protons of 2 and 3 compared to those of 1 and 4. The methylene protons adjacent to the serine hydroxy groups involved in ester formation (δ 4.44 [4H] for 2 and δ 4.43 [2H] for 3) are shifted downfield relative to the methylene protons adjacent to the free serine hydroxy group (δ 3.95 [1H], δ 3.83 [1H] for 2 and δ 3.94 [1H], δ 3.82 [1H] for 3). The 1H NMR correlations of 4 are consistent with the reported values.10 Additional NMR experiments, 13C, HSQC and HMBC further confirm that 4 is chrysobactin (Table 2, Supporting Information Figures S10–S13).

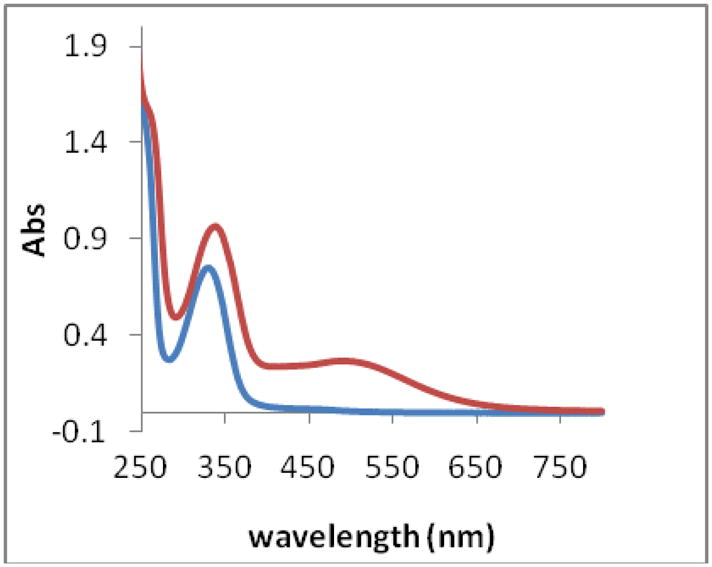

The UV-visible spectrum of Fe(III)-cyclic trichrysobactin is shown in Figure 3. A characteristic catecholate-to-Fe(III) ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) transition is observed in the visible region around 500 nm (ε499nm = 3910 M−1cm−1).13, 14

Figure 3.

UV-visible spectra of apo-cyclic trichrysobactin (blue) and Fe(III) cyclic trichrysobactin (red). [Fe(III) cyclic trichrysobactin] = 0.08 mM, in 80 mM MOPS pH 7.00. (1 cm path length cuvettes).

The absolute configuration at the metal center is a primary recognition point by outer membrane siderophore receptor proteins.15 Interestingly, the ferric complexes of enterobactin and bacillibactin have opposite chirality in their Fe(III) complexes, despite their structural similarities. Fe(ent)3− adopts a Δ configuration and Fe(bb)3− adopts a Λ configuration.14 The chirality of the Fe(III)-cyclic trichrysobactin (Fe(III)-1) complex was analyzed by circular dichroism (CD) (Supporting Information Figure S18). The transitions in the visible region of the CD spectrum of Fe(III)-cyclic trichrysobactin are consistent with the reported CD transitions observed for the tris-complex of ferric chrysobactin.16 The positive CD band around 515 nm (Δε [M−1 cm−1] = +2.6) indicates that the ferric complex of cyclic trichrysobactin has a Λ configuration, similar to the ferric bacillibactin complex. The CD band at 350 nm arises from the chirality of the peptide backbone.14

In summary, D. chrysanthemi EC16 produces a new triscatecholate siderophore, cyclic trichrysobactin (1), as well as a linear trichrysobactin (2), dichrysobactin (3) and the monomer unit, chrysobactin (4). Whether compounds 2–4 are actual siderophores or simply hydrolysis products of 1, is not currently known. The ESIMS, MS/MS, and NMR analyses presented here establish that 1 is a triscatecholamide siderophore comprised of three chrysobactin units joined by a tri-serine lactone backbone. The lysine spacer between DHBA and serine units differentiates 1 from the other triscatecholate siderophores shown in Figure 1.

Chrysobactin (4), is a previously reported siderophore originally isolated from Dickeya dadantii 3937, (formerly known as E. chrysanthemi and P. chrysanthemi).10, 17 D. chrysanthemi is a plant pathogen that causes soft rot in a variety of plants. More recently, chrysobactin has been isolated from another plant pathogen E. carotova subsp. carotovora W3C105.18 Chrysobactin mediated iron(III)-uptake in D. dadantii 3937 plays an important role in plant infection and in fact, the production of chrysobactin by D. dadantii 3937 is required for virulence.19–21

It is well recognized that hexadentate enterobactin has a much higher affinity for iron(III) than triscatecholate complexation,1, 22 as established by comparison of the pM values: pM is a measure of concentration of Fe(III) left uncomplexed in solution (specifically –log[Fe(III)]uncomplexed) under conditions of 1 mM Fe(III) and 10 mM ligand, at a defined pH. For example, the pM value for FeIIIent3− at pH 7.4 is 35.5, whereas that for the triscatecholate complex of 2,3-dihydroxy-N-N-dimethylbenzamide (DMB), FeIII(DMB)33− is ~15.23, 24 The pM value for FeIII(chrysobactin)3 has been estimated to be about 17.3, although a mixture of species may be present.16, 25 Therefore, we anticipate the Fe(III) stability constant with the hexadentate cyclic trichrysobactin (1) to be much larger than chrysobactin (4). Experiments are in progress to examine the solution thermodynamics of Fe(III)-1.

The biosynthesis of chrysobactin (4) in D. dadantii 3937 is carried out by a previously identified nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS).26–29 The biosynthesis of cyclic trichrysobactin produced by P. chrysanthemi EC16 is anticipated to occur similarly, although with two sequential repetitions of the NRPS system leading to the triserine lactone of cyclic trichrysobactin. Given that the biosynthetic pathways for enterobactin and chrysobactin are remarkably similar, it is not surprising that a cyclic trichrysobactin has been identified. Perhaps, in previous work cyclic trichrysobactin was not identified in D. dadantii 3937 due to the susceptibility of the tri-serine lactone to hydrolysis in aqueous solutions. Nevertheless, the question remains, whether cyclic trichrysobactin is specific to D. chrysanthemi EC16, or whether it could also be produced by D. dadantii 3937? Investigations are underway to probe siderophore biosynthesis in D. chrysanthemi EC16.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

A Varian Cary-Bio 300 UV-visible spectrophotometer was used for ultraviolet and visible spectrophotometry. Circular dichroic (CD) spectra were recorded on an AVIV 202 spectrophotometer. 1D (1H and 13C), and 2D (1H-1H gCOSY, 1H-1H TOCSY, HSQC, and HMBC) NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance II 800 Ultrashield Plus spectrometer with a cryoprobe in d4-methanol (CD3OD; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). Molecular masses and partial connectivity of the chrysobactins (1–4) were determined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESIMS) and tandem mass spectrometry (ESIMS/MS), with argon as a collision gas, using a Micromass QTOF-2 mass spectrometer (Waters Corp.).

Bacterial Strain

Dickeya chrysanthemi EC16 (previously known as E. chrysanthemi and P. chrysanthemi)17 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC strain 11662). The bacterial strain was maintained on Difco Luria Bertani (LB) Miller (BD Biosciences) medium plates.

Culture and Isolation

Growth conditions for D. chrysanthemi EC16 were modified from a previously published procedure.10 For siderophore production, a single colony of D. chrysanthemi EC16 was inoculated into 200 mL of Difco LB Millar (BD Biosciences) media and grown overnight at 30 °C shaking at 180 RPM. 10 mL of the overnight culture of D. chrysanthemi EC16 was then inoculated into a low-iron minimal nutrient medium (2 L, pH 7.4) containing trace metal grade NaCl (0.1 M), KCl (0.01 M), MgSO4 (0.8 mM), NH4Cl (0.02 M), citric acid (23.8 mM), Na2HPO4 (0.02 M) and g1ycerol (41 mM) in acid-washed Erlenmeyer flasks (4 L). The liquid chrome azurol sulfonate (CAS)11 test was used to indicate the presence of iron(III)-binding ligands in the culture medium. Two 2 L cultures were grown at room temperature on an orbital shaker (180 RPM) for approximately 48 h, after which cells were removed by centrifugation (6000 RPM, 30 min). Cultures were in the stationary phase of growth at the time of harvesting. Amberlite XAD-2 resin (Supelco) was added to the cell-free culture supernatant (ca. 100g/L) and shaken for 3 h at 120 RPM. The supernatant was filtered off, and the XAD-2 resin was then transferred into a glass chromatography column (2 cm internal diameter, i.d.), and washed with doubly deionized H2O (2 L). Siderophores were eluted with 100% MeOH (400 mL). The MeOH eluent was concentrated under vacuum. Siderophores were purified by RP-HPLC on a preparative C4 column (22 mm i.d., × 250 mm length, Vydac) with a gradient from H2O (doubly deionized with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)) to 50% MeOH over 57 min. The eluent was continuously monitored at 215 nm. Fractions were collected manually and concentrated under vacuum. Fractions containing siderophores were identified by the CAS assay. Siderophores were further purified by RP-HPLC with a semi-preparative C4 column (10 mm i.d. × 250 mm L, Vydac) using the same program as outlined above. Purified siderophores were lyophilized and stored at −80 °C. Siderophores eluted at 23.2 min (4), 33.8 min (3), 37.5 min (2) and 38.7 min (1). Approximately 1.5 mg of cyclic trichrysobactin (1), 1.0 mg of chrysobactin (4) and 0.5 mg of linear trichrysobactin and dichrysobactin (2 and 3) were isolated per 2 L culture.

Cyclic Trichrysobactin (1)

yellow-brown oil; UV λMOPS, pH 7max (log ε) 330 nm (3.97); CDΔε (M−1 cm−1) (354 nm) = +11.02 (MOPS, pH 7, c = 0.09 mM); 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR data, Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 1054.4369 [M+H]+ (calcd for C48H63N9O18, 1054.4349).

Linear Trichrysobactin (2)

yellow-brown oil; UV λMOPS, pH 7max (log ε) 328 nm (3.91); CDΔε (M−1 cm−1) (353 nm) = +12.82 (MOPS, pH 7, c= 0.06 mM); 1H and 13C data, Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 1072.4475 [M+H]+ (calcd for C48H65N9O19, 1072.4432).

Dichrysobactin (3)

yellow-brown oil; 1H and 13C data, Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 721.3045 [M+H]+ (calcd for C32H44N6O13, 721.3021).

Chrysobactin (4)

yellow-brown oil; 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR data, Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 370.1614 [M+H]+ (calcd for C16H24N3O7, 370.1597).

Chiral Amino Acid Analysis

Dry samples of purified chrysobactins (1–4) (~0.5 mg each) were hydrolyzed in HCl (6M; 200 μL) for 17 h at 110 °C. Solutions were brought to room temperature, evaporated to dryness and re-dissolved in H2O (100 μL). A 1% (w/v) solution (200 μL) of Marfey’s reagent (Nα-(2,4-dinitro-5-fluorophenyl)-L-alaninamide (FDAA))12 in acetone along with NaHCO3 (1M, 40 μL) was added to the siderophore hydrolysate solution. The reaction was heated for 1 hr at 40 °C, after which HCl (2 M; 20 μL) was added to terminate the reaction. The derivatized samples were analyzed by HPLC on an analytical YMC ODS-AQ C18 column (4.6 mm, i.d. × 250 mm L, Waters Corp.) using a linear gradient from 90% triethylamine phosphate (TEAP) (50 mM; pH 3.0)/10% CH3CN to 60% TEAP (50 mM; pH 3.0)/40% CH3CN over 45 min. The eluent was continuously monitored on a Waters UV-visible detector (340 nm). The derivatized samples were compared to chiral amino acid standards prepared the same way. Assignments were confirmed by coinjection of the derivatized siderophore sample with amino acid standards. Retention times (min) of the FDAA amino acid derivatives used as standards were: L-serine (21.2 (mono-α-derivative), 44.6 (bis-derivative)), D-serine (23.5 (mono-α-derivative), 48.9 (bis-derivative)), L-lysine (18.5 (mono-α-derivative), 24.0 (mono-ε-derivative), 44.7 (bis-derivative)), D-lysine (19.8 (mono-α-derivative), 24.0 (mono-ε-derivative), 49.0 (bis-derivative)). FDAA derivatized hydrolysis products of 1 were: D-lysine (19.1, 24.0, 48.9), L-serine (21.0, 44.4). FDAA derivatized hydrolysis products of 2 were: D-lysine (19.3, 24.6, 49.1), L-serine (21.2, 44.8). FDAA derivatized hydrolysis products of 3 were: D-lysine (19.3, 24.4, 48.9), L-serine (21.0, 44.8). FDAA derivatized hydrolysis products of 4 were: D-lysine (19.5, 24.8, 49.0), L-serine (21.2, 44.9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding from NIH GM38130 (A.B.) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank J. Pavlovich (MS) and H. Zhou (NMR) at UCSB and R. Radford (CD) and A. Tezcan (CD) at UCSD for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: The RP-HPLC trace of the MeOH XAD-2 extract of the supernatant of P. chrysanthemi EC16, ESIMS/MS spectra of 2–4, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of 1–4, and 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC Spectra of 1 and 4, tabulated NMR data for 2 and 3 and the CD spectrum of Fe(III)-1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Loomis LD, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:906–911. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dertz EA, Stintzi A, Raymond KN. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:1087–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obrien IG, Gibson F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;215:393–401. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(70)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollack JR, Neilands JB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38:989–992. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson MK, Abergel RJ, Raymond KN, Arceneaux JEL, Byers BR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bister B, Bischoff D, Nicholson GJ, Valdebenito M, Schneider K, Winkelmann G, Hantke K, Sussmuth RD. BioMetals. 2004;17:471–481. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000029432.69418.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patzer SI, Braun V. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:426–435. doi: 10.1128/JB.01250-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandy M, Han A, Blunt J, Munro M, Haygood M, Butler A. J Nat Prod. 2009;73:1038–1043. doi: 10.1021/np900750g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soengas RG, Anta C, Espada A, Paz V, Ares IR, Balado M, Rodriguez J, Lemos ML, Jimenez C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7113–7116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persmark M, Expert D, Neilands JB. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3187–3193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marfey P, Ottesen M. Carlsberg Res Comm. 1984;49:585–590. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karpishin TB, Gebhard MS, Solomon EI, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2977–2984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bluhm ME, Hay BP, Kim SS, Dertz EA, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:5475–5478. doi: 10.1021/ic025531y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abergel RJ, Zawadzka AM, Hoette TM, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12682–12692. doi: 10.1021/ja903051q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persmark M, Neilands JB. BioMetals. 1992;5:29–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01079695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samson R, Legendre J, Christen R, Saux M, Achouak W, Gardan L. Int J Syst Evol Microbio. 2005;55:1415–1427. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes HH, Ishimaru CA. BioMetals. 1999;12:83–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1009223615607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enard C, Diolez A, Expert D. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2419–2426. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2419-2426.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franza T, Mahe B, Expert D. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:261–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neema C, Laulhere JP, Expert D. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:967–973. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avdeef A, Sofen SR, Bregante TL, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:5362–5370. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris WR, Carrano CJ, Cooper SR, Sofen SR, Avdeef AE, McArdle JV, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:6097–6104. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris WR, Carrano CJ, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:2722–2727. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomisic V, Blanc S, Elhabiri M, Expert D, Albrecht-Gary AM. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:9419–9430. doi: 10.1021/ic801143e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franza T, Enard C, Vangijsegem F, Expert D. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1319–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franza T, Expert D. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6874–6881. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6874-6881.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauscher L, Expert D, Matzanke BF, Trautwein AX. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2385–2395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franza T, Expert D. In: Iron Uptake and Homeostasis in Microorganims. Cornelis P, Andrews SC, editors. Caister Academic Press; Norfolk, UK: 2010. pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.