Abstract

Objective

The authors sought to clarify the structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for 22 DSM-IV disorders: 12 common axis I disorders and all 10 axis II disorders.

Method

The authors examined syndromal and subsyndromal axis I diagnoses and five categories reflecting number of endorsed criteria for axis II disorders in 2,111 personally interviewed young adult members of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel.

Results

Four correlated genetic factors were identified: axis I internalizing, axis II internalizing, axis I externalizing, and axis II externalizing. Factors 1 and 2 and factors 3 and 4 were moderately correlated, supporting the importance of the internalizing-externalizing distinction. Five disorders had substantial loadings on two factors: borderline personality disorder (factors 3 and 4), somatoform disorder (factors 1 and 2), paranoid and dependent personality disorders (factors 2 and 4), and eating disorders (factors 1 and 4). Three correlated environmental factors were identified: axis II disorders, axis I internalizing disorders, and externalizing disorders versus anxiety disorders.

Conclusions

Common axis I and II psychiatric disorders have a coherent underlying genetic structure that reflects two major dimensions: internalizing versus externalizing, and axis I versus axis II. The underlying structure of environmental influences is quite different. The organization of common psychiatric disorders into coherent groups results largely from genetic, not environmental, factors. These results should be interpreted in the context of unavoidable limitations of current statistical methods applied to this number of diagnostic categories.

Psychiatric disorders are clinical-historical constructs whose etiology and pathophysiology are largely unknown, and hence most psychiatric nosologies, including DSM-IV (1) and ICD-10 (2), arrange disorders into categories primarily on the basis of clinical similarities. Our field has long hoped for an etiologically based classification of psychiatric disorders. Of the possible organizing principles for such an approach, familial/genetic factors have frequently been emphasized (3–5).

The potential utility of examining the broad structure of psychiatric and substance use disorders was first demonstrated by Krueger and colleagues (6–8) and then by others (e.g., references 9, 10). These analyses, examining a range of epidemiological samples, provided consistent evidence that common psychiatric disorders could be divided into two broad categories: internalizing disorders—dominated by major depression and anxiety disorders—and externalizing disorders—dominated by antisocial personality disorder and drug and alcohol use disorders.

Such epidemiological investigations, while instructive, do not directly provide insight into the causes of the patterns of co-occurrence. By contrast, similar studies performed in genetically informative samples, such as twins, can distinguish between the structures of psychiatric disorders produced by genetic factors on the one hand and environmental factors on the other. However, it might be asked: What is the value of such an approach in the genomic era? Examining the impact of individual molecular variants on risk for multiple psychiatric disorders will explain only very small proportions of the shared genetic variance (11). Twin studies, by contrast, assess aggregate genetic effects and therefore examine the degree of sharing across disorders of all genetic risk variants. While molecular methods can lead to a clarification of common pathophysiological pathways, the global questions that psychiatric nosologists have traditionally been interested in (e.g., how closely related genetically are two disorders?) can be best addressed at the aggregate level using genetically informative designs like twin studies (12).

One previous study examined seven common psychiatric and substance use disorders in members of the Virginia Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders (13). Consistent with previous epidemiological investigations, that study identified two genetic factors that loaded strongly on, respectively, three internalizing disorders (major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobias) and four externalizing disorders (alcohol dependence, drug abuse or dependence, antisocial personality disorder, and conduct disorder). A parallel analysis of the effects of the environmental factors did not produce clear internalizing and externalizing factors, which suggests that genetic rather than environmental factors are responsible for the coherent underlying structure of common psychiatric disorders. Other researchers have documented the genetic coherence of an externalizing dimension of psychopathology (e.g., references 14, 15).

The present study, conducted in the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel (NIPHTP), represents a follow-up and expansion of our earlier effort (13) in two critical ways. First, we examined a much broader array of common axis I disorders. Second, while the previous study included only one axis II disorder (antisocial personality disorder), the present analysis includes all 10 of the DSM-IV personality disorders. This addition permitted us, for the first time, to study systematically the genetic and environmental relationships between axis I and axis II disorders, a key component of the current conceptual framework for psychiatric disorders first introduced in DSM-III (16). One limitation of our approach is worth highlighting. Despite our relatively large sample, many of the individual disorders we wished to study were too rare to be examined solely at a fully syndromal level. Therefore, for the personality disorders, as we have done in the past (17–19) and others have advocated (20–24), we examined the number of endorsed criteria. For most of the axis I disorders, we also examined patients with subsyndromal cases (and show that such individuals had disorders that reflected milder manifestations of the same underlying liability as those with fully syndromal disorders).

The goal of this study, then, was to investigate the underlying genetic and environmental structure of a large proportion of common axis I DSM-IV disorders and all DSM-IV axis II disorders. We sought to clarify for the first time the broad structure of common axis I and axis II psychiatric syndromal and subsyndromal disorders as seen from an etiological perspective, in this case from a genetic point of view.

Method

Sample and Assessment Methods

Twins were recruited from the NIPHTP (25). Twins in the NIPHTP were identified through the Norwegian National Medical Birth Registry, which was established on January 1, 1967, and receives mandatory notification of all live births. Questionnaire studies were previously conducted in 1992 (twins born 1967–1974) and in 1998 (twins born 1967–1979). Altogether, 12,698 twins received the second questionnaire, and 8,045 (3,334 pairs and 1,377 single responders) responded after one reminder (cooperation rate, 63%).

The data for this analysis are from an interview study, conducted from 1999 to 2004, assessing DSM-IV axis I and axis II disorders (26). Interviewers were largely senior clinical psychology students at the end of their 6-year training course (including at least 6 months of clinical practice) and psychiatric nurses with years of clinical experience. They were trained by professionals with extensive experience with the instrument. The interviews were mostly conducted face-to-face, although for practical reasons 231 interviews (8.3%) were conducted by telephone. Each twin in a pair was interviewed by a different interviewer.

As outlined in detail elsewhere (26), the 6,442 eligible participants were defined as the 3,153 complete pairs in which both members completed the second questionnaire and agreed to be contacted again, as well as 68 pairs unintentionally drawn directly from the NIPHTP.

Altogether, 2,794 twins (44% of those eligible) were interviewed. Noncooperation was overwhelmingly the result of nonresponse to the written invitation; active refusals were rare (0.8%) (26). The study was approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethical Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they received a complete description of the study. Of those interviewed, 36.5% were male, and the mean age was 28.2 years (SD=3.9).

As outlined elsewhere (27), zygosity was determined by the use of questionnaire items for the entire sample (28) and by micro-satellite markers for 676 of the like-sex pairs, which, when used together in a discriminant analysis for participants for whom DNA was unavailable, predicted a zygosity misclassification rate of ~1% of pairs, a rate far too low to substantially bias results (29).

These analyses included only the same-sex pairs from this sample—2,111 individuals, including both members of 669 monozygotic and 377 dizygotic pairs and 19 individual twins without their co-twin. Only twin pairs in which both twins initially had agreed to participate were interviewed; for the 19 individual twins, the co-twin changed his or her mind after the initial consent.

Axis I Disorders

Axis I disorders other than conduct disorder were assessed using a Norwegian computerized version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) (30)—a comprehensive structured diagnostic interview assessing DSM-IV axis I disorders (1) that has been shown to have good test-retest and interrater reliability (31–33). Both the paper-and-pencil version and the computerized version of the M-CIDI have previously been used in Norway (34, 35).

Twelve axis I disorders were included in these analyses: major depression, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, eating disorders, somatoform disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, illicit drug abuse or dependence, and conduct disorder. Except for conduct disorder, initial analyses of these disorders were performed using DSM-IV diagnoses automatically generated by the M-CIDI data program. However, stable solutions were unobtainable because of small or zero cell frequencies for a number of these diagnoses. We therefore created three ordered categories (unaffected, subsyndromal, and fully syndromal) for 10 of these disorders, which substantially improved the stability of our estimates. Our definitions for the subsyndromal categories are detailed briefly in Table 1 and in more detail in Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

TABLE 1.

Summary Criteria for Subthreshold Forms of Common Axis I Disorders

| Disorder | Summary Criteria for Subthreshold Form of the Disorder |

|---|---|

| Panic disorder | Assessed using two probe questions evaluating criterion A1 and required the experience of a panic attack without being in danger. |

| Agoraphobia | Assessed by a probe question evaluating criterion A and required reporting a strong fear of being away from home, traveling in a bus or train, being in a public place, traveling alone, or crossing a bridge. |

| Phobia | Assessed by a probe question evaluating criterion A and required an unusually strong fear or avoidance of living things, the sight of blood, getting an injection, going to the dentist or hospital, heights, storms, thunder or lightning, being in water, flying in an airplane, being in a closed space, or any other specified situation. |

| Social phobia | Assessed by two probe questions for criterion A and required an unusually strong fear or avoidance of seven possible social situations (e.g., eating, drinking, or writing while being watched, participating or speaking in a meeting) in addition to a fear of behaving in nine possible ways (e.g., showing anxiety, throwing up, losing control of bladder or bowels, blushing). |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Assessed by a probe question evaluating criterion A and required the occurrence of a period of feeling worried, tense, or anxious most of the time for a minimum duration of 3 months. |

| Eating disorder | Assessed from criterion A for anorexia nervosa and criteria A and B for bulimia nervosa and required either loss of at least 6.5 kg and being perceived as too thin, or a period of binge eating and strict dieting, a lot of exercise, use of medication, vomiting, or fasting. |

| Somatoform disorder | Assessed by probe questions addressing criterion A of conversion disorder, criterion 5 of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, criterion B of somatization disorder, criterion A of undifferentiated somatization disorder, criterion A of hypochondriasis, and criterion A of pain disorder. |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | Required the admission of having had periods of drinking too much and consuming at least five units of alcohol per day twice a month or more. |

| Drug abuse or dependence | Required the use of illicit or improper use of prescribed drugs 10 or more times to get high. Nicotine dependence is not included. |

| Conduct disorder | Rating by interviewer as subthreshold (≥1) conduct disorder A criterion. |

We assessed the validity of our subsyndromal categories in two ways. First, we compared all the cross-disorder phenotypic correlations using the original dichotomous full-syndrome variables (tetrachoric correlations) with the three-category variables (polychoric correlations); 95% confidence intervals for these two correlations overlapped for 65 of 66 correlations. Second, using a multiple-threshold model in PRELIS 2.3 (36), we tested whether the three categories represented differing levels of severity on a single continuum of liability. This test failed at the 5% level three of 46 times, consistent with chance expectations (37).

The phenotypic tetrachoric and polychoric correlations for this sample between all 22 axis I and II disorders examined in these analyses are listed in Table S2 in the online data supplement.

Axis II Disorders

A Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) (38) was used to assess all 10 DSM-IV personality disorders and conduct disorder. The DSM-III-R and DSM-IV versions of this interview have been used previously in large-scale studies in Norway (39, 40). The SIDP-IV, a comprehensive semistructured diagnostic interview for the assessment of DSM-IV personality disorders, contains nonpejorative questions organized into topical sections rather than by individual personality disorder, thereby improving the interview flow. The SIDP-IV interview was conducted after the M-CIDI, which helped to distinguish long-standing behaviors from temporary states resulting from axis I disorders.

The SIDP-IV uses the “5-year rule,” meaning that behaviors, cognitions, and feelings that predominated for most of the past 5 years are judged to be representative of an individual’s personality. Each DSM-IV criterion is scored on a 4-point scale (0=absent, 1=subthreshold, 2=present, or 3=strongly present). To keep results parallel with other personality disorders, we examined only the A criterion for antisocial personality disorder.

With traditional cutoff scores, too few individuals met full DSM-IV criteria for the 10 personality disorders for statistical analysis (17–19). We therefore modeled the personality disorders as an ordinal count of the number of positively endorsed criteria. Furthermore, defining a criterion to be present with a score of 1 or higher produced more stable results than using a cutoff of 2 or higher. This approach is justified by results from previous studies of these 10 personality disorders (17–19) in which, using a multiple-threshold model, we showed that the four response options for scoring individual personality disorder criteria reflected varying levels of “severity” on a single continuum of liability.

Because few individuals endorsed most of the criteria for individual personality disorders, we collapsed the total criterion count into five categories to reduce the frequency of null cells. We have also tested the validity of this approach by examining the fit of the multiple-threshold model, which asks whether the number of endorsed criteria reflects differences of severity on a single normal continuum of liability. This assumption was supported for all 10 personality disorders (17–19). For ease of expression, we refer in this article to “personality disorders” in place of the more accurate but cumbersome term “five categories of endorsed criteria for personality disorders.” We previously reported the high inter-rater reliability for the assessed personality disorder obtained by two raters scoring 70 audiotaped interviews (27) (intraclass correlations for number of endorsed criteria ranged from 0.81 to 0.96).

Statistical Methods

Our analytic approach involved three major steps: 1) estimating polychoric correlations for 44 (2×22) variables, including within-twin cross-disorder, cross-twin within-disorder, and cross-twin cross-disorder correlations, for monozygotic and dizygotic twins separately; 2) estimating genetic and environmental correlations between all 22 disorders, based on multivariate biometric modeling; and 3) applying exploratory factor analysis to the resulting genetic and environmental correlation matrices.

First, monozygotic and dizygotic polychoric correlations with corresponding asymptotic weights were estimated in Mplus 5.21 for the monozygotic and same-sex dizygotic twin pair data (41). The robust weighted least squares mean and variance estimator was used. Under this method, all twin correlations for all disorder variables are estimated pairwise using all available ordinal raw data for each combination of variables. The weights are the estimated variances of these correlation parameters. These were obtained in Mplus using the TECH3 output and save data options. These asymptotic variances up- or down-weight the contribution of each of the respective polychoric correlations.

Next, a saturated Cholesky decomposition of the monozygotic and dizygotic twin correlations among our 22 disorders was performed in Mx. A diagonally weighted least squares fit function was implemented in Mx (42) to maximize the agreement between the observed statistics and those predicted by the model. The squared deviations between observed and expected correlations were weighted by the inverse of the asymptotic covariances of each statistic; these weights were computed using Mplus. Because of the large number of variables in the model, we had to use limited-information diagonally weighted least squares instead of the more desirable full-information maximum-likelihood approach. A diagonally weighted least squares fit function was implemented in Mx to fit a two-group (monozygotic and dizygotic pairs) Cholesky model including additive genetic (A) and unique environmental (E) parameters to these estimated polychoric correlations and asymptotic weights. Because standard estimating functions could not be used, ordinary statistical indexes were not available to evaluate model-data fit and to compare nested models.

After obtaining estimates of the A and E parameters of the Cholesky decomposition model, the estimated Cholesky path coefficients were converted and rescaled into A and E correlation matrices for the 22 variables, which then served as the input to exploratory factor analyses performed in Mplus 5.21. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted using an unweighted least squares estimator because of the nonpositive definite properties of the A and E correlation structures. The geomin rotation method in Mplus was used to obtain the oblique rotation of the chosen exploratory factor analysis solution. We used oblique rotations because we wanted to examine the magnitude of the relationship between the resulting genetic and environmental factors.

The exploratory factor analysis of the genetic correlation matrix produced four eigenvalues above unity: 9.88, 3.19, 1.85, and 1.53. A scree plot was consistent with an inflection break at either three or four factors. The fourth factor identified a coherent factor of five disorders (genetic factor 4 below) and so merited retention. By contrast, a fifth factor included only one syndrome with a substantial loading (eating disorders)—a clear sign of overextraction. Furthermore, the four-factor solution provides a reasonable summary of the matrix of genetic correlations seen in Table S3 in the online data supplement.

Exploratory factor analysis of the specific environmental correlation matrix revealed six factors with eigenvalues exceeding unity: 5.17, 2.70, 1.46, 1.34, 1.19, and 1.10. Examining the scree plot suggests a break between three and four factors. Adding a third factor identified a coherent bipolar factor with salient loadings on five disorders (environmental factor 3 below). Adding a fourth factor, by contrast, identified a minimally coherent factor with loadings on only two disorders—positive on drug abuse or dependence and negative on dependent personality disorder. We again saw this as evidence of overextraction, so we present results from a four-factor genetic and a three-factor unique environmental solution.

Results

The estimated genetic and environmental correlation matrices are presented in Tables S3 and S4 in the online data supplement. Table 2 presents the heritability of the individual disorders estimated from our model.

TABLE 2.

Estimated Proportion of Variance in Liability to Common DSM-IV Axis I and All Axis II Disorders Due to Genetic Effects (Heritability) and Individual-Specific Environment

| Disorder | Heritability (a2) | Individual-Specific Environmental Effects (e2) |

|---|---|---|

| Major depression | 0.43 | 0.57 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.51 | 0.49 |

| Eating disorder | 0.42 | 0.58 |

| Social phobia | 0.57 | 0.43 |

| Agoraphobia | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| Specific phobia | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| Somatoform disorder | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| Dysthymia | 0.28 | 0.72 |

| Panic disorder | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| Drug abuse or dependence | 0.59 | 0.41 |

| Conduct disorder | 0.57 | 0.43 |

| Paranoid personality disorder | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Schizoid personality disorder | 0.34 | 0.66 |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 0.38 | 0.62 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Histrionic personality disorder | 0.32 | 0.68 |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | 0.35 | 0.65 |

| Dependent personality disorder | 0.37 | 0.63 |

| Avoidant personality disorder | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 0.34 | 0.66 |

Genetic Factors

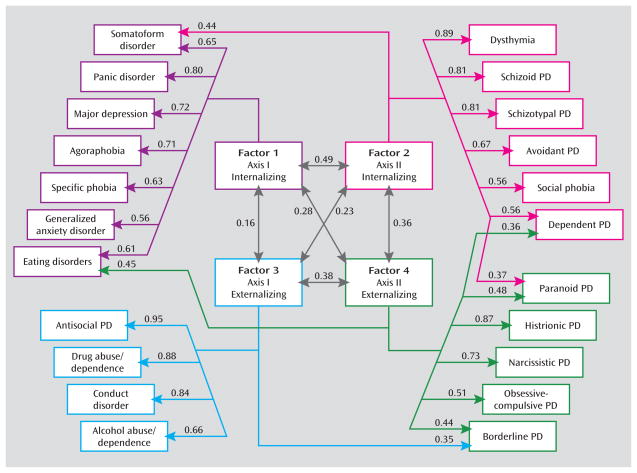

Parameter estimates from the four genetic factors are presented in Table 3 and in Figure 1 (which includes all paths accounting for ≥10% of the genetic variance, that is, with loadings >0.316). Three broad patterns of findings are noteworthy. First, the four factors are all coherent and substantively interpretable. Factor 1 has strong loadings on four anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder), major depression, eating disorders, and somatoform disorders. This factor reflects axis I internalizing disorders. Factor 2 is dominated by four personality disorders—schizoid, schizotypal, avoidant, and dependent—as well as dysthymia and social phobia. We name this factor axis II internalizing disorders, although it also contains two disorders traditionally placed on axis I. Factor 3 has strong loadings on four disorders reflecting antisocial behaviors (conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder) and substance use disorders (alcohol and drug abuse or dependence). This factor identifies an axis I externalizing disorders dimension although it includes one category (antisocial personality disorder) that is traditionally placed on axis II. Factor 4 contains the five remaining personality disorders—histrionic, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, borderline, and paranoid—and is best interpreted as an axis II externalizing disorders dimension.

TABLE 3.

Geomin Rotated Genetic Factor Loadings for Syndromal and Subsyndromal Common DSM-IV Axis I and All Axis II Disordersa

| Disorder | Factor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Axis I Internalizing | 2. Axis II Internalizing | 3. Axis I Externalizing | 4. Axis II Externalizing | |

| Panic disorder | 0.80 | −0.08 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| Major depression | 0.72 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Agoraphobia | 0.71 | 0.11 | 0.29 | −0.11 |

| Somatoform disorder | 0.65 | 0.44 | −0.20 | −0.13 |

| Specific phobia | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Eating disorder | 0.61 | −0.02 | −0.18 | 0.45 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| Dysthymia | 0.18 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Schizoid personality disorder | −0.18 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.21 | −0.07 |

| Avoidant personality disorder | 0.01 | 0.67 | −0.11 | 0.20 |

| Dependent personality disorder | 0.07 | 0.56 | −0.02 | 0.36 |

| Social phobia | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.05 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Drug abuse or dependence | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.07 |

| Conduct disorder | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.84 | −0.06 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 0.01 | −0.22 | 0.66 | 0.23 |

| Histrionic personality disorder | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.13 | 0.87 |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | −0.30 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.73 |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.51 |

| Paranoid personality disorder | 0.18 | 0.37 | −0.05 | 0.48 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.44 |

Shaded cells indicate loadings ≥ √0.10, or ≥0.316.

FIGURE 1.

Parameter Estimates From the Best Overall Model for Genetic Factors for Syndromal and Subsyndromal Common DSM-IV Axis I and All Axis II Disordersa

aFour factors were identified using an oblique geomin rotation. Only those paths are depicted that account for more than 10% of the genetic variance in disease liability—that is, have a path estimate of ≥0.316. For all path estimates in the model, see Table 3. PD=personality disorder.

Second, the interfactor correlations quantify the degree of sharing of genetic risk factors for these four groupings of disorders. Most closely related are the two internalizing disorder factors (correlation = 0.49) followed by the two externalizing factors (0.38). The two axis II groups are moderately intercorrelated (0.36), and the correlation between the two axis I groups was quite low (0.16).

Third, five disorders had notable cross-loadings on other factors: somatoform disorder (loadings from both factors 1 and 2), borderline personality disorder (factors 3 and 4), eating disorders (factors 1 and 4), and both paranoid and dependent personality disorders (factors 2 and 4).

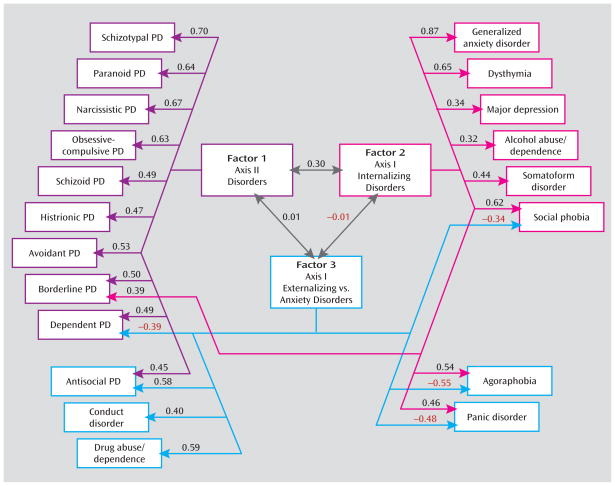

Environmental Factors

The factor loadings for the three environmental factors are presented in Table 4 and Figure 2 (which includes all paths with loadings ≥0.316). Four broad patterns of findings are noteworthy. First, two disorders are missing in Figure 2—eating disorders and specific phobia, which did not load appreciably on any of the three environmental factors. Second, the overall factor pattern does not resemble that seen for the genetic factors. The first factor includes nine of the 10 axis II disorders and reflects a common set of environmental experiences that predispose nonspecifically to all forms of personality disorders. Factor 1 can best be termed axis II personality disorders. Factor 2 loads primarily on axis I internalizing disorders, including most (but not all) of the anxiety disorders, major depression, dysthymia, and somatoform and eating disorders. Alcohol abuse or dependence also loads moderately on this factor, which nonetheless is probably most accurately identified as an axis I internalizing disorders factor. The third factor had substantial positive loadings on three of the classical externalizing disorders (antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, and drug abuse or dependence) and negative loadings on agoraphobia and panic disorder.

TABLE 4.

Geomin Rotated Environmental Factor Loadings for Syndromal and Subsyndromal Common DSM-IV Axis I and All Axis II Disordersa

| Disorder | Factor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Axis II Disorders | 2. Axis I Internalizing Disorders | 3. Externalizing Versus Anxiety Disorders | |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 0.70 | −0.01 | −0.15 |

| Paranoid personality disorder | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | 0.67 | −0.09 | 0.13 |

| Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder | 0.63 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Avoidant personality disorder | 0.53 | 0.03 | −0.23 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.13 |

| Schizoid personality disorder | 0.49 | −0.11 | −0.18 |

| Dependent personality disorder | 0.49 | 0.06 | −0.39 |

| Histrionic personality disorder | 0.47 | 0.08 | −0.03 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.58 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | −0.12 | 0.87 | 0.01 |

| Dysthymia | 0.19 | 0.65 | 0.00 |

| Social phobia | −0.14 | 0.62 | −0.34 |

| Agoraphobia | 0.10 | 0.54 | −0.55 |

| Panic disorder | 0.20 | 0.46 | −0.48 |

| Somatoform disorder | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.26 |

| Major depression | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | −0.11 | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Drug abuse or dependence | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.59 |

| Conduct disorder | 0.30 | −0.05 | 0.40 |

| Specific phobia | −0.09 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| Eating disorders | −0.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

Shaded cells indicate loadings ≥ √0.10, or ≥0.316.

FIGURE 2.

Parameter Estimates From the Best Overall Model for Individual-Specific Environmental Factors for Syndromal and Subsyndromal Common DSM-IV Axis I and All Axis II Disordersa

aThree factors were identified using an oblique geomin rotation. Only those paths are depicted that account for more than 10% of the individual-specific environmental variance in disease liability—that is, have a path estimate of ≥0.316. For all path estimates in the model, see Table 4. Two disorders—eating disorders and specific phobia—are not represented in this figure because they failed to load substantially on any of the three identified factors. PD=personality disorder.

Third, the modest interfactor correlation observed between factors 1 and 2 (correlation = 0.30) indicates some sharing of environmental risk factors for axis II disorders and axis I internalizing disorders. However, the correlations between factors 1 and 3 and factors 2 and 3 are essentially zero, which suggests that there is no sharing of predisposing environmental experiences across these groups.

Fourth, the six disorders that had substantial loadings on two factors provide further insights into the structure of environmental risks for psychiatric disorders. Antisocial personality disorder was transitional between factors 1 and 3, and agoraphobia and panic disorder between factors 2 and 3. Factor 3 had secondary negative cross-loadings on two additional anxiety/dysphoria disorders: social phobia and dependent personality disorder.

Discussion

Our goal in this study was to clarify the structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common axis I disorders and all axis II personality disorders as assessed by a criterion count. Using multivariate twin analyses, we identified, from the 22 disorders examined, four coherent genetic factors: axis I internalizing, axis II internalizing, axis I externalizing, and axis II externalizing.

Although not without important limitations (see below), these findings provide, for the first time, a view of the etiological structure of a substantial proportion of common psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, this structure, especially the genetic factors, is coherent and clinically sensible. The structure of the genetic risks for these disorders is neither extremely simple (e.g., just one dimension of underlying risk) nor bewilderingly complex. Of the many interesting results from these analyses, three are particularly noteworthy.

First, we replicated and extended the results of our earlier multivariate twin analysis, which included only seven disorders but clearly identified genetic internalizing and externalizing factors (13). The present study provides further support for the importance and generalizability of the internalizing and externalizing genetic dimensions of risk for common psychiatric disorders. While we identified separate internalizing and externalizing factors for axis I and II disorders, they were moderately intercorrelated.

Second, our results provide—for the first time to our knowledge—some support, from a genetic perspective, for the decision in DSM-III to distinguish between axis I and axis II disorders. The genetic substrate for axis II disorders is, in our analyses, at least partially separable from those factors that predispose to axis I disorders. However, the axis I and II disorders that loaded on our genetic factors are not isomorphic with those articulated by DSM-III. Two axis I disorders—dysthymia and social phobia—were included in the internalizing axis II cluster. The concept of dysthymia evolved in part from the concept of “depressive personality” (16, 43). Our results suggest that from a genetic perspective, it may be better placed with the personality disorders than in the mood disorders section. A debate has long simmered about the relationship between social phobia and avoidant personality disorder (see, for example, references 44–47). Our results suggest that from a genetic perspective, social phobia belongs with avoidant personality disorder on axis II.

Our results supporting a genetic distinction between axis I and axis II disorders might be seen as surprising, given previous evidence that they are highly comorbid and hard to distinguish empirically (48). Another plausible interpretation of our findings, particularly for internalizing disorders, is that different sets of genetic risk factors predispose to psychiatric disorders that are typically transient and episodic in nature and those that are characteristically more chronic.

Third, “transitional” disorders with substantial loadings on two genetic factors provide further insights into the structure of the genetic risk for psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, the existence of these transitional disorders indicates that the psychiatric disorders in our current classification do not neatly fall into our four proposed clusters. Individuals with high criterion counts for borderline personality disorder were predicted by our results to require elevated genetic risk for both axis I and II externalizing disorders. Paranoid personality disorder stood out because it required risk genes from both the axis II internalizing and externalizing dimensions. Eating disorders had the most unusual configuration, requiring high risk on both the axis I internalizing and the axis II externalizing dimensions.

We also identified three unique environmental factors. The first resulted from environmental experiences predisposing to all personality disorders. The second reflected environmental factors altering risk solely to internalizing axis I disorders. Consistent with our Virginia study (13), with respect to individual-specific environmental risk factors, alcohol abuse or dependence more closely resembled major depression and generalized anxiety disorder than antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, or drug abuse or dependence. The third environmental factor reflected environmental exposures that predisposed to the anxiety disorders while protecting against the core externalizing disorders (or vice versa). The inverse relationship between anxiety and externalizing traits is, in our analyses, largely environmental in origin.

It is illustrative to compare the location of a few sets of disorders in genetic versus environmental space. From a genetic perspective, dysthymia sorts with the personality disorders, yet its environmental risk factors place it much closer to major depression. Environmentally, alcohol abuse or dependence shares most risk factors with internalizing disorders but shares genetic risk factors with the axis I externalizing disorders. Environmentally, borderline personality disorder has links with all personality disorders and with axis I internalizing disorders; genetically, it is closely tied to axis I and II externalizing disorders.

Consistent with our earlier study (13), the division of common psychiatric disorders into internalizing versus externalizing factors results from genetic and not from environmental risk factors. By contrast, the division into axis I versus axis II disorders arises from the effects of both genes and the environment.

Our results are also congruent with our previous analysis in this sample of the structure of genetic risk factors for personality disorders (27). That study, which examined only the 10 personality disorders, identified three genetic factors, the first of which loaded most heavily on histrionic, narcissistic, and borderline personality disorders—clearly reflecting our axis II externalizing factor. The second factor loaded more specifically on antisocial and borderline personality disorders—approximating our broader axis I externalizing genetic factor. The third genetic factor loaded most heavily on avoidant and schizoid personality disorders, with weaker loadings on dependent and schizotypal personality disorders—reflecting our axis II internalizing genetic factor.

Limitations

These results need to be interpreted in the context of nine additional potentially significant limitations. First, our results are obtained in native-born young adult Norwegian twins and may not generalize to other ethnic or age groups.

Second, as many important psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, autism, bipolar illness) were not included in these analyses, no claims can be made for our identification of the structure of risk factors for all psychiatric illness.

Third, using traditional statistical methods, we were unable to estimate results separately in male and female participants. While we controlled for prevalence differences across the sexes, we cannot rule out the possibility that we have averaged results of the two sexes that might meaningfully differ from one another. However, three findings reduce our concern that we have thereby introduced significant biases in our findings. In our earlier multivariate study in the Virginia Twin Registry (13), once we accounted for differences in prevalence, we were able, in a much larger twin sample, to constrain to equality parameter estimates across the sexes. In all of our previous analyses of the axis I and II disorders in this Norwegian sample, we have failed to find evidence for sex-specific genetic or environmental effects (17–19, 27, 49–52). Finally, we examined several models of our 22 disorders treating the criterion counts and subthreshold and threshold diagnoses as normally distributed variables. While this approach does not correctly capture the distributional properties of our variables, it nonetheless provides some useful information. Compared to the full model with separate parameter estimates for male and female participants, a model constraining all the genetic and environmental parameters to equality in the two sexes provided a much better fit using the Bayesian information criterion, a fit index particularly well suited for complex models (53).

Fourth, we were unable to test, using standard twin model fitting, whether the addition of shared environmental factors would improve the fit of this large multivariate model. However, a wide range of previous analyses with most of the disorders included in our model failed to find evidence for substantial shared environmental effects (17–19, 27, 47, 49–52, 54). Furthermore, treating the criterion counts and subthreshold and threshold diagnoses as normally distributed, we compared the full model and a model that dropped all of the shared environmental parameters. It fitted much better using the Bayesian information criterion and also was clearly superior to a model that dropped all the additive genetic parameters. While we cannot rule out a modest degree of confounding of genetic with shared environmental effects, it is unlikely that this confounding is substantial.

Fifth, we could not formally test the number of genetic and environmental factors extracted. We therefore had to rely on the more traditional methods of the scree plot and clinical interpretation. We feel confident, however, that four genetic and three specific environmental factors represent the most parsimonious structure that well accounts for the observed results.

Sixth, we lacked the ability to calculate confidence intervals for the individual parameter estimates. Given the size of our sample, we suspect that our parameter estimates are known with only moderate accuracy (55). However, it is the broad pattern of our findings rather than the specific value of any individual parameter that is probably of greatest value in these analyses.

Seventh, substantial attrition was observed from the original birth registry through three waves of contact. However, detailed analyses of the predictors of nonresponse across waves (26) revealed that cooperation was strongly predicted by sex, zygosity, age, and education but not psychiatric symptoms or self-report personality disorder items that have been shown empirically to predict DSM-IV personality disorder criteria in the personal interview phase. For example, among 45 predictors, including 22 mental health variables, only two—older age and monozygosity—predicted cooperation in the personal interview phase. Twin analyses of 25 mental health-related variables from earlier questionnaires reflecting psychiatric and personality disorder symptoms and substance use revealed no significant differences between those who completed a personal interview and those who did not (26). Thus it is unlikely that attrition introduced bias in the estimates of the etiological role of genetic and environmental risk factors for this broad range of mental health indicators. Our sample is probably broadly representative of the Norwegian population with respect to psychopathology.

Eighth, could our results be sensitive to the specific method of factor extraction? In addition to the oblique geomin rotations, we examined solutions obtained by the orthogonal varimax and oblique promax methods. All four genetic factors and the first environmental factor were stable across rotational methods, with only small differences on the second and third environmental factors (e.g., higher cross-loadings for antisocial personality disorder and drug abuse or dependence). The main features of our results, especially the four genetic factors, were stable with respect to the method of factor extraction.

Finally, could method variance account for critical parts of our findings? We used two separate instruments with different formats for the assessment of axis I versus conduct and personality disorders. However, our results suggest that this concern is unwarranted. Our second genetic factor contained five axis II personality disorders and two axis I disorders. Antisocial personality disorder and conduct disorder, both assessed in our personality disorder interview, were placed in the third genetic factor and the third environmental factor each time with other axis I disorders. This pattern of results is not consistent with a method variance account.

Conclusions

We have long sought to ground our diagnostic categories in etiological processes. While not free of methodological limitations, this study nonetheless provides, for the first time, a comprehensive picture of the structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for most common DSM-IV axis I disorders and all axis II disorders. The genetic structure of these disorders, as indexed by syndromal and subsyndromal diagnoses of the axis I disorders and criterion counts for the personality disorders, was relatively simple, consisting of four factors reflecting the two major dimensions of internalizing versus externalizing and axis I versus axis II. However, for five disorders, substantial genetic influences from two of these factors were required to adequately explain their etiology. The structure of the environmental influences on these disorders, by contrast, looked quite different, indicating that the organization of common psychiatric disorders into these coherent groups was largely a result of genetic and not environmental influences. Our findings reinforce accumulating evidence over the past half century that genetic factors play a critical role not only in the etiology of individual disorders but also in the structure of disorders as they occur and co-occur in human populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grant MH-068643 and grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, the Norwegian Council for Mental Health, and the European Commission under the program “Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources” of the Fifth Framework Program (no. QLG2-CT-2002-01254).

Footnotes

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126:983–987. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraepelin E. In: Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians (Translation of Psychiatrie) 6. Metoui H, translator. Vol. 1. Canton, Mass: Science History Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kretschmer E. Physique and Character. London: Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): a longitudinal-epidemiological study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG. The higher-order structure of common DSM mental disorders: internalization, externalization, and their connections to personality. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:1245–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: the NEMESIS study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slade T, Watson D. The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, Faraone SV, Gejman PV, Kelsoe J, Lehner T, Levinson DF, Moran A, Sklar P, Sullivan PF Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Coordinating Committee. Genomewide association studies: history, rationale, and prospects for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:540–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS. Reflections on the relationship between psychiatric genetics and psychiatric nosology. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1138–1146. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, McGue M, Patrick CJ. Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders: a twin-family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young SE, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Krauter KS, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibition. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:684–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. (DSM-III) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Aggen SH, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Dimensional representation of DSM-IV cluster A personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: a multivariate study. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1583–1591. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torgersen S, Czajkowski N, Jacobson K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roysamb E, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Dimensional representations of DSM-IV cluster B personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: a multivariate study. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1617–1625. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Neale MC, Orstavik RE, Torgersen S, Tambs K, Roysamb E, Harris JR, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental influences on dimensional representations of DSM-IV cluster C personality disorders: a population-based multivariate twin study. Psychol Med. 2007;37:645–653. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Charting the future of axis II. J Pers Disord. 2000;14:17–29. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Bender DS, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Morey LC, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG. Dimensional representations of DSM-IV personality disorders: relationships to functional impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1919–1925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widiger TA, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: finding a common ground. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:110–130. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.2.110.62628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widiger TA, Samuel DB. Diagnostic categories or dimensions: a question for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:494–504. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramer V, Torgersen S, Kringlen E. Personality disorders and quality of life: a population study. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel: a description of the sample and program of research. Twin Res. 2002;5:415–423. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tambs K, Ronning T, Prescott CA, Kendler KS, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Torgersen S, Harris JR. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health twin study of mental health: examining recruitment and attrition bias. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:158–168. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Czajkowski N, Roysamb E, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for DSM-IV personality disorders: a multivariate twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1438–1446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health twin program of research: an update. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:858–864. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neale MC. A finite mixture distribution model for data collected from twins. Twin Res. 2003;6:235–239. doi: 10.1375/136905203765693898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittchen HU, Pfister H. DIA-X Interviews (M-CIDI): Manual für Screening-Verfahren und Interview: Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Erganzungsheft (DIA-X-Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-12 Monate); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-12 Monate); PC-Programm zur Durchführung des Interviews (Längsund Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt, Germany: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the World Health Organization–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H. Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:568–578. doi: 10.1007/s001270050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubio-Stipec M, Peters L, Andrews G. Test-retest reliability of the computerized CIDI (CIDI-Auto): substance abuse modules. Subst Abuse. 1999;20:263–272. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kringlen E, Torgersen S, Cramer V. A Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1091–1098. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landheim AS, Bakken K, Vaglum P. Gender differences in the prevalence of symptom disorders and personality disorders among polysubstance abusers and pure alcoholics: substance abusers treated in two counties in Norway. Eur Addiction Res. 2003;9:8–17. doi: 10.1159/000067732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. PRELIS 2: User’s Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feild H, Armenakis A. On use of multiple tests of significance in psychological research. Psychol Rep. 1974;35:427–431. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Iowa City: University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helgeland MI, Kjelsberg E, Torgersen S. Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1941–1947. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical Modeling. Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University Medical School, Department of Psychiatry; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider K. Psychopathic Personalities. London: Cassell; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reich J. Avoidant personality disorder and its relationship to social phobia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rettew DC. Avoidant personality disorder, generalized social phobia, and shyness: putting the personality back into personality disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:283–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ralevski E, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Tracie Shea M, Yen S, Bender DS, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Avoidant personality disorder and social phobia: distinct enough to be separate disorders? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Orstavik RE, Tambs K, Kendler KS. The relationship between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia: a population-based twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1722–1728. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krueger RF. Continuity of axes I and II: toward a unified model of personality, personality disorders, and clinical disorders. J Pers Disord. 2005;19:233–261. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Illicit psychoactive substance use, abuse, and dependence in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins. Psychol Med. 2006;36:955–962. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ørstavik RE, Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The relationship between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder: a population-based twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1866–1872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tambs K, Czajkowsky N, Roysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Aggen SH, Harris JR, Orstavik RE, Kendler KS. Structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for dimensional representations of DSM-IV anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:301–307. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kendler KS, Myers J, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The heritability of cluster A personality disorders assessed by both personal interview and questionnaire. Psychol Med. 2007;37:655–665. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markon KE, Krueger RF. An empirical comparison of information-theoretic selection criteria for multivariate behavior genetic models. Behav Genet. 2004;34:593–610. doi: 10.1007/s10519-004-5587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazzeo SE, Mitchell KS, Bulik CM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Assessing the heritability of anorexia nervosa symptoms using a marginal maximal likelihood approach. Psychol Med. 2009;39:463–473. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS. The power of the classical twin study to resolve variation in threshold traits. Behav Genet. 1994;24:239–258. doi: 10.1007/BF01067191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.