Abstract

FGF1, a widely expressed proangiogenic factor involved in tissue repair and carcinogenesis, is released from cells through a nonclassical pathway independent of endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Although several proteins participating in FGF1 export were identified, genetic mechanisms regulating this process remained obscure. We found that FGF1 export and expression are regulated through Notch signaling mediated by transcription factor CBF1and its partner MAML. The expression of a dominant negative (dn) form of CBF1 in 3T3 cells induces transcription of FGF1 and sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1), which is a component of FGF1 export pathway. dnCBF1 expression stimulates the stress-independent release of transduced FGF1 from NIH 3T3 cells and endogenous FGF1 from A375 melanoma cells. NIH 3T3 cells transfected with dnCBF1 form colonies in soft agar and produce rapidly growing highly angiogenic tumors in nude mice. The transformed phenotype of dnCBF1 transfected cells is efficiently blocked by dn forms of FGF receptor 1 and S100A13, which is a component of FGF1 export pathway. FGF1 export and acceleration of cell growth induced by dnCBF1 depend on SphK1. Similar to dnCBF1, dnMAML transfection induces FGF1 expression and release, and accelerates cell proliferation. The latter effect is strongly decreased in FGF1 null cells. We suggest that the regulation of FGF1 expression and release by CBF1-mediated Notch signaling can play an important role in tumor formation.

Keywords: CBF1, FGF1, MAML, Notch, cell transformation, melanoma, S100A13, SphK1

Introduction

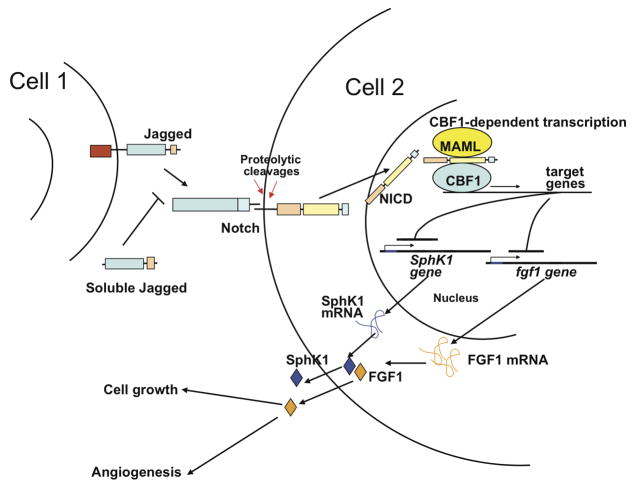

The Notch and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) pathways are two ubiquitous metazoan signaling systems that play critical roles in embryonic and postnatal development of the organism (Fortini, 2009; Ornitz and Itoh, 2001). Transmembrane Notch receptors (Notch 1–4) specifically bind transmembrane Notch ligands (Jagged 1 and 2, Delta-like 1, 3 and 4) located on neighboring cells (Sahlgren and Lendahl, 2006). The interaction between a Notch receptor and its ligand results in a series of proteolytic cleavages and production of a soluble cytosolic intracellular Notch receptor domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus where it binds the transcription factor CBF1 (also known as RBPJ and CSL) (Fortini, 2009). This binding is followed by the recruitment of the nuclear protein MAML1 and formation of a ternary complex (CBF1+NICD+MAML), that functions as a transcriptional activator of CBF1-dependent genes (Leong and Karsan, 2006). Notch signaling has been demonstrated to be crucial for embryonic and postnatal development including vasculogenesis, heart development, vein/artery specification, and angiogenesis (Gridley, 2007).

The effects of Notch signaling are mediated by its interplay with other signaling pathways. Among them is the evolutionarily conserved FGF/FGFR signaling system - (Katoh, 2007). FGF signaling plays important roles in the formation and maintenance of the cardiovascular system and in the pathology of several types of tumors (Presta et al., 2005). Biological activities of the FGFs are exerted through four transmembrane protein kinase receptors (FGFR1-4) and thus require FGF access to the extracellular environment (Ornitz and Itoh, 2001). While most FGFs are exported through the classical endoplasmic reticulum- (ER) and Golgi-mediated secretion mechanism, two members of the family, FGF1 and FGF2, which are ubiquitously expressed in the mammalian organism, do not contain a signal peptide in their primary structure, and thus are exported independently of the ER-Golgi (Nickel, 2005; Prudovsky et al., 2008). FGF1 export is induced by cellular stresses, such as heat shock, hypoxia and serum starvation (Prudovsky et al., 2008), and FGF1 is released as a part of a copper-dependent multiprotein complex, which also contains the small calcium-binding protein S100A13 (Landriscina et al., 2001), p40 kDa form of synaptotagmin 1 (LaVallee et al., 1998) and sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) (Soldi et al., 2007).

Although, considerable knowledge has accumulated about the nonclassical export of FGF1 and other signal peptide-less proteins (Nickel and Rabouille, 2009; Prudovsky et al., 2008) the information about its genetic regulation is scarce. We reported that the expression of a recombinant soluble form of the Notch ligand Jagged1 (sJg1), corresponding to the extracellular domain of Jagged1, attenuated Notch signaling (Small et al., 2001). Interestingly, sJg1 expression also stimulated the transcription and export of FGF1 (Small et al., 2003). We hypothesize that Notch signaling suppresses FGF1 expression and release. Following this hypothesis, repression of CBF1-dependent Notch signaling should result in FGF-dependent enhancement of cell proliferation. Indeed, in certain cell types, such as keratinocytes (Demehri et al., 2009; Kolev et al., 2008) and pancreatic ductal cells (Hanlon et al.), down regulation of Notch signaling results in cell transformation, however, the role of FGF signaling in this phenomenon has not been studied. The complexity of the problem is increased by the reports that in addition to CBF1, Notch signaling proceeds through CBF1-independent pathways (Nofziger et al., 1999; Perumalsamy et al.; Sanalkumar et al.; Sanalkumar et al.). To understand the role of CBF1 signaling in the regulation of FGF1 expression and secretion, and in FGF-dependent cell transformation we used dominant negative mutants of CBF1 (dnCBF1) and MAML (dnMAML). We found that the export of FGF1 and the expression of FGF1 and sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1), a protein of the FGF1 release complex, are under negative control by CBF1, and the inhibition of CBF1-dependent transcription results in the acquisition of the FGFR- and FGF1-dependent transformed cell phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Genetic constructs

The dnCBF1 (pCMX-N/RBP-J (R218H)) construct was received from the RIKEN BRC DNA bank (Tsukuba, Japan), where it had been deposited by T. Honjo (University of Kyoto, Japan). dnCBF1 open reading frame was further cloned in the multiple cloning site of the vector pcDNA3.1Myc (Invitrogen). A dominant negative mutant of Xenopus laevis FGF receptor 1 (dnFGFR1) comprising the extracellular and transmembrane domains of FGFR1 but lacking its cytoplasmic domain was cloned into the adenoviral expression vector pAdLox. A dominant negative form of S100A13 (6Myc:dnS100A13) (Landriscina et al., 2001) lacking ten C-terminal amino acids was also cloned in pAdLox. β-galactosidase (LacZ) expressing adenovirus was purchased through Quantam Biotechnologies. Retroviral dnMAML:GFP construct was obtained from Jon Aster (Harvard University). In this construct, aminoacids 12–74 of human MAML, which are C-terminally tagged with EGFP, were cloned in the retroviral construct Mig R1.

Cell Culture

Murine NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and stable NIH 3T3 cell transfectants were maintained in DMEM (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). Stable transfectants were additionally supplemented with 0.4 g/l Geneticin (Invitrogen-GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA.). A375 melanoma cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), immortalized SphK1 +/+ and SphK1 null mouse embryo fibroblasts (Soldi et al., 2007), immortalized FGF1+/+ and FGF1 null mouse osteoblasts (Miller et al., 2000) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT).

Immortalization of FGF1 null cells

FGF1 null (Miller et al., 2000)and wild type (WT) mouse osteoblasts were propagated in DMEM (Hyclone) with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone). After two passages, osteoblasts stopped proliferating and two weeks later foci of immortalized cells appeared. Immortalized fibroblasts were propagated for at least 100 passages. Immortalized FGF1 null and WT cells were analyzed by PCR using primers specific for the first FGF1 exon and their genotypes were confirmed.

Generation of stable cell transfectants

NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC) were transfected with dnCBF1:Myc, and the respective empty vector using the Fugene reagent (Roche) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Transfected cell clones were selected in medium containing 800 μg/ml G418. The expression of dnCBF1:Myc in isolated transfected clones was tested by immunoblotting using anti-Myc antibodies (Covance).

Production of viruses and viral transfection

Recombinant adenoviruses were produced, purified and titrated as described (Hardy et al., 1997). Briefly, CRE8 cells were transfected with SfiI-digested pAdlox-derived constructs, and infected with the ψ5 virus. Lysates were prepared 2 days after infection. Viruses were passed twice through CRE8 cells, and purified from the second passage using a cesium density gradient. The viruses were quantified by optical density at 260 nm, and the bioactivity was determined by the plaque forming unit assay.

Adenoviral transduction was performed in serum-free DMEM with approximately 103 viral particles/cell in the presence of poly-D-Lysine hydrobromide (Sigma) (5×103 molecules/viral particle) for 2 hours at 37°C. Then the adenovirus-containing medium was removed and replaced with serum-containing medium. Cells were plated for experiments 24–48 hours after transduction. The efficiency of transduction for dnFGFR1 and dnS100A13:6Myc was assessed by immunofluorescence using respectively monoclonal anti-FGFR1 antibodies (Neilson and Friesel, 1995) and monoclonal anti-Myc antibodies (Covance) followed by the secondary FITC-conjugated antibodies.

dnMAML retrovirus was produced in the Recombinant Viral Vector Core of MMCRI. The packaging cell line Bosc was transfected with the dnMAML:GFP coding retroviral construct using polybrene. Conditioned medium from the 2 days culture of producer cell line was collected and filtered to remove cell debris. Actively growing recipient cells were incubated for 2 h with retrovirus-containing conditioned medium in the presence of 5 μg/ml hexadimethrine bromide. The medium was replaced with fresh growth medium after 2 h. After 48 h, GFP fluorescence was observed in 30–70% of the cells. Cells were then trypsinized, and GFP-positive cells were selected using flow cytometry (FACSVantage, BD) in the Flow Cytometry Core of MMCRI.

Luciferase assays of transcriptional activity

To assess the effect of dnCBF1 on CBF1-mediated transcription, stable transfected cells and vector- transfected control cells were plated on fibronectin-coated (10 μg/cm2) cell culture dishes at approximately 50% confluence, and transiently co-transfected using Fugene 6 (Roche) with 500 ng of a luciferase construct driven by four tandem copies of the (CBF1) response element. Co-transfection with 100 ng of the TK Renilla (Promega) construct was used as internal control for transfection efficiency. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and the luciferase/renilla activity measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Similar approach was applied to assess the effect of dnCBF1 upon the activity of the SphK1 promoter. In this experiment, we compared NIH 3T3 cells preliminary transduced with the adenoviruses coding for dnCBF1 and LacZ (control). A reporter construct containing the luciferase cDNA under the 5′ UTR (5200 bp) of the human SphK1 gene (gift of Lina Obeid, University of South Carolina) was used.

Analysis of FGF1 and SphK1 expression

RT-PCR analysis of FGF1 expression was performed with total RNA isolated from dnCBF1 transfected and control vector transfected cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Total RNA (1 μg) was used as a template for the PCR reaction performed with the Platinum Tap One Step RT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen). The following PCR primers were utilized: forward 5′-ATGGCTGAAGGGGAGATCACAACC-3′ and reverse 5′-CGCGCTTACAGCTCCCGTTC-3′. Cyclophilin or β-actin expression served as a control for RNA loading. The amplification products were visualized by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Similar method was used to analyze SphK1 expression in NIH 3T3 cells adenovirally transduced with dnCBF1 or LacZ (control). The following primers were used: forward 5′-CTTCTGGGCTGCGGCTCTATTCTG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTGCCCGTGGTTGCTTTCC-3′.

Microarray analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was isolated form NIH 3T3 cell 48 h after adenoviral transduction with dnCBF1 or LacZ (control) using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Comparative analysis of differential gene expression induced by dnCBF1was performed using Agilent Whole Muse Genome Oligo Microarrays.

Analysis of FGF1 release

Cells were used for the studies of FGF1 release 48 h after adenoviral transduction with FGF1. The heat shock-induced FGF1 release assay was performed by incubation of cells at 42°C for 110 minutes in serum-free DMEM containing 5 U/ml of heparin (Sigma), as previously described (Jackson et al. 1992). Control cultures were incubated at 37°C for the same period. Conditioned media were collected, filtered, and FGF1 was isolated for immunoblot analysis using heparin-Sepharose chromatography. Cell viability was assessed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the medium using the Promega CytoTox kit. In the experiments with A375 melanoma cells, endogenous FGF1 was isolated by heparin-Sepharose chromatography form cells lysates prepared by the treatment of cell pellets with 1% Triton X100.

Cell growth rate analysis

To assess cell growth rate, cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in TC6 plates or at 5,000 or 10,000 cells per well in TC12 plates. At days 1–12 after plating, cells were trypsinized and counted using a hematocytometer. Four wells were counted for each time point.

DNA synthesis assay

dnCBF1 transfectant NIH 3T3 cells and control vector transfectants were plated on fibronectin coated glass coverslips, grown to 100% confluency and transferred to quiescence medium containing 0.2% serum. Forty eight hours later, BrDu was added to the medium in final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Twenty four hours after that, cells were fixed in 100% ethanol, treated with 1 N HCl at 50°C and immunofluorescently stained with mouse monoclonal anti-BrDu antibodies (Dako) followed by secondary FITC-conjugated antibodies. The percentage of BrDu labeled cells was determined using the combination of fluorescence and phase contrast microscopy.

Colony formation in soft agar

NIH 3T3 cells transfected with dnCBF1 or with empty vector were plated in TC6 well plates with 0.5% agar cushion, in the overlay containing DMEM, 10% BCS (Hyclone) and 0.33% agar at 1000 cells per well. As indicated, some dishes were also treated with 1μM of the FGFR-specific inhibitor, PD1666866 (a generous gift from RL Panek, Pfizer). In a separate series of experiments, cells were transduced with dnFGFR1, dnS100A13 or LacZ (control) encoding adenoviruses, and plated in soft agar 24 h after transduction. Cells were fed with 0.5 ml of fresh medium every 4 days. Eighteen days after plating, the colonies were stained with p-iodonitrotetrazolium (Sigma) for visualization. Quantification of colony formation was achieved by counting all violet-stained colonies visible by naked eye.

Tumor formation on chicken CAM and in nude mice

Tumor formation on chicken CAM was studied using chicken embryos from Charles River Laboratories. NIH 3T3 cells were adenovirally transduced with LacZ or dnCBF1. Next day, 40 μl drops of DMEM containing 2×106 of LacZ or dnCBF1 transduced cells were placed through the windows in the egg shells onto the chicken embryo CAMs. Embryos were incubated for additional 7 days and then tumor formation was assessed.

To assess the ability of dnCBF1 transfected cells to form tumors in mice, 2×106 dnCBF1 or vector transfectant cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of a 4-week-old female nude mice (Taconic). Animals were used in compliance with the guidelines of NIH, and the use of animals was approved by the MMCRI IACUC. Four mice were used for each cell type. When tumors reached the diameter of 7 mm, mice were euthanized and tumors fixed in 10% neutral formalin. Paraffin sections of tumors were prepared by the Histopathology Core of Maine Medical Center Research Institute. For morphological studies, deparaffinized sections were stained with hematoxylin. To assess the vascularization of tumors, deparaffinized section were processed for immunoperoxidase detection of endothelial marker CD31/PECAM (anti-PECAM antibodies from Dako were used).

Results

1. Inhibition of CBF1-dependent transcription stimulates FGF1 expression and non-classical release of FGF1

To address the role of CBF1-mediated Notch signaling in FGF1 export, we stably transfected NIH 3T3 cells with an expression construct that encodes dnCBF1 containing the point mutation R218H in the DNA-binding domain of CBF1, which converts it into a potent negative regulator of the CBF1-dependent transcription (Chung et al., 1994) apparently as a result of sequestration of NICD. We obtained several clones of NIH 3T3 transfectants with different levels of dnCBF1 expression. Clone 9 with high dnCBF1 expression (Figure 1A) was used in further experiments. As a control, we used NIH 3T3 cells stably transfected with an expression vector containing the gene of neomycin transferase.

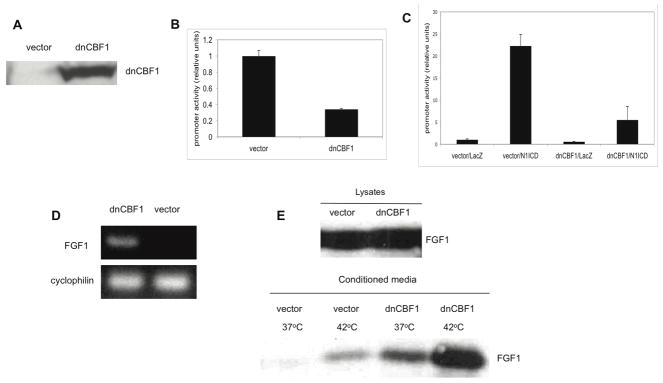

Figure 1. dnCBF1 expression results in the inhibition of CBF1-dependent transcription, stimulation of FGF1 expression and stress-independent FGF1 export.

A. Immunoblotting assay of dnCBF1:Myc expression in transfectant NIH 3T3 cells. Lysates of 5×105 of dnCBF1- and vector-transfected cells were loaded per lane and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Anti-Myc monoclonal antibodies were used for immunoblotting. B. Luciferase assay of CBF1-dependent transcription in dnCBF1 transfectant NIH 3T3 cells and control vector transfected cells. Cells were transiently co-transfected with a TK-renilla construct and a CBF1-luciferase construct. CBF1-dependent promoter activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent S.D. C. Luciferase assay of dnCBF1 effect upon N1ICD-stimulated CBF1-dependent transcription. dnCBF1 transfectant NIH 3T3 cells and control vector transfected cells were adenovirally transduced with N1ICD or LacZ and then transiently co-transfected with a TK-renilla construct and a CBF1-luciferase construct. Error bars represent S.D. D. RT-PCR assay of endogenous FGF1 transcription in vector- and dnCBF1-transfected cells. Cyclophilin was used as loading control. E. dnCBF1- and vector-transfected cells were adenovirally transduced with FGF1. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 or 42°C in serum-free medium. FGF1 was isolated from the medium using heparin-Sepharose chromatography, and 10% of cell lysate or FGF1 equivalent of the total medium were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using rabbit anti-FGF1 antibodies.

CBF1-dependent transcription was evaluated in the dnCBF1 transfected cells by using a luciferase gene reporter under the control of a promoter containing four CBF1-binding elements as previously described (Small et al., 2003). dnCBF1 transfection resulted in a more than three-fold decrease of the CBF1-dependent transcription as compared to control vector-transfected cells (Figure 1B). In additional experiments, we verified that dnCBF1 also strongly suppressed CBF1 signaling induced by cell transduction with Notch1 ICD (Figure 1C).

The RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that dnCBF1 transfectant cells were characterized by the induction of FGF1 transcription (Figure 1D). Despite the induction of FGF1 transcription, its level in dnCBF1 transfectant NIH 3T3 cells was not sufficient to reliably evaluate FGF1 release. Thus, the study of FGF1 export was performed on cells adenovirally transduced with FGF1 as previously described (Duarte et al., 2008). We found that unlike vector transfected cells, which released FGF1 only after heat shock, dnCBF1 transfected cells spontaneously released FGF1 at normal temperature at a level similar to the heat-shock stimulated export from control cells (Figure 1E). Heat shock of dnCBF1 transfected cells resulted in an additional increase in FGF1 export.

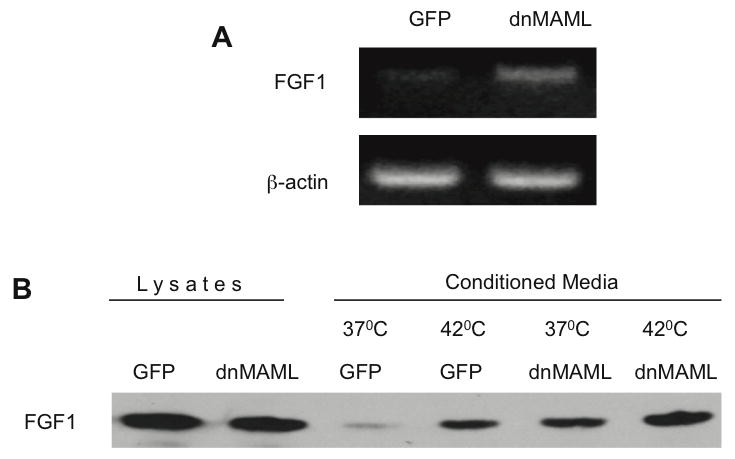

The results obtained using dnCBF1 expressing cells were further confirmed using cells stably transduced with a retroviral construct expressing a dominant negative form of another key component of the CBF1 complex - transcription factor MAML. dnMAML:GFP-transduced cells exhibited enhanced transcription of endogenous FGF1 (Figure 2A) and stress-independent export of adenovirally transduced FGF1 (Figure 2B) as compared with control NIH 3T3 cells expressing GFP

Figure 2. Similar to dnCBF1, dnMAML expression results in stimulation of FGF1 expression and release.

A. RT-PCR assay of endogenous FGF1 transcription in dnMAML:GFP and GFP expressing cells. β-actin was used as loading control. B. dnMAML:GFP and GFP expressing cells were adenovirally transduced with FGF1. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 or 42°C in serum-free medium. FGF1 was isolated from the medium using heparin-Sepharose chromatography, and 10% cell lysate or FGF1 equivalent of the total medium were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using rabbit anti-FGF1 antibodies.

2. Cells with inhibited CBF1-dependent transcription exhibit a transformed phenotype in vitro

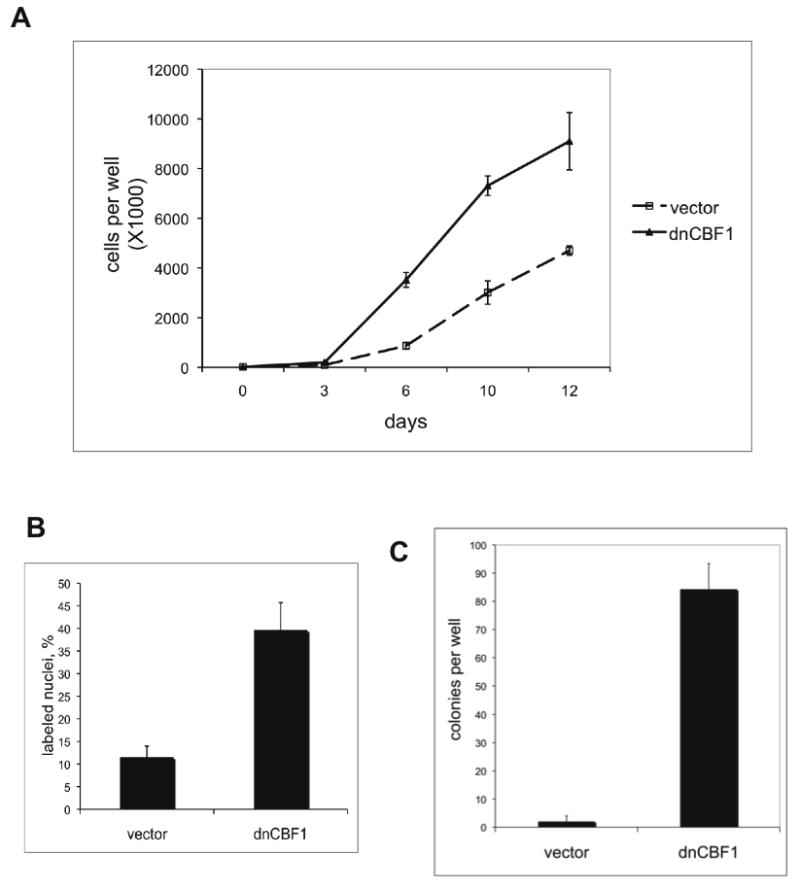

FGF1 is a potent mitogen, and genetic attachment of an N-terminal signal peptide to FGF1 converts it to an oncogene (Forough et al., 1993). Because dnCBF1 induces FGF1 expression and release, we decided to assess whether the suppression of the CBF1-dependent transcription induces the transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. In the first series of experiments, we compared the growth rates of dnCBF1- and vector-transfected cells. Cells were plated at equal densities, and cell numbers were monitored over a period of 12 days. We found that dnCBF1 induced a strong increase in cell growth rate (Figure 3A). In the next experiment, we used BrDu labeling to elucidate the ability of dnCBF1 transfectant cells to exit cell cycle under quiescence conditions. We demonstrated that in serum deprived cultures the percentage of replicating dnCBF1 transfectants was at least three times higher than in case of vector transfectants (Figure 3B). We also assessed the ability of dnCBF1 to induce anchorage-independent cell growth, another characteristic of the transformed phenotype. dnCBF1 transfected and control cells were plated at low density in soft agar and allowed to grow for 2.5 weeks. By the end of that period, dnCBF1 transfected cells formed multiple colonies visible by naked eye (results of colonies count present on Figure 3C), while most of vector transfected cells died as a result of anoikis, and only rare groups of 2 or 3 cells were observed under microscope (data not shown).

Figure 3. dnCBF1 expression results in the acceleration of NIH 3T3 cells proliferation and formation of colonies in soft agar.

A. dnCBF1 expressing or vector transfected NIH 3T3 cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in TC6 plates. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 3, 6, 10 and 12 after plating. B. dnCBF1 transfectant NIH 3T3 cells and control vector transfectants were plated on glass coverslips, grown to 100% confluency and transferred to quiescence medium containing 0.2% serum. Forty eight hours later, BrDu was added to the medium. Twenty four hours after that, cells were fixed and the percentage of labeled cells was determined using immunofluorescence microscopy. C. dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were plated in 0.3% agar at 1,000 cells per well in TC6 plates. Eighteen days after plating, the colonies were stained with p-iodonitrotetrazolium and counted.

3. Inhibition of FGFR signaling abolishes the transformed phenotype of cells with attenuated Notch signaling

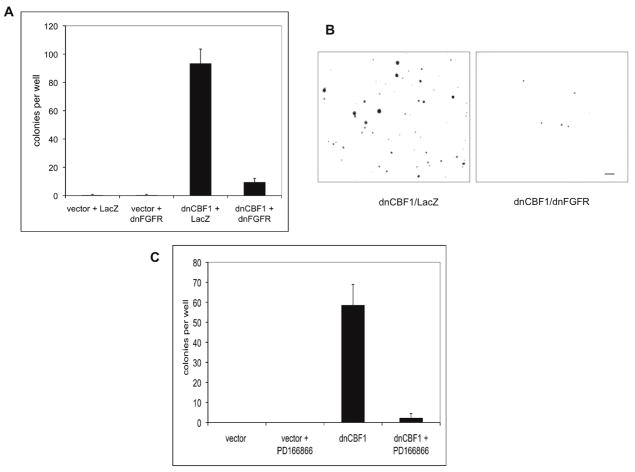

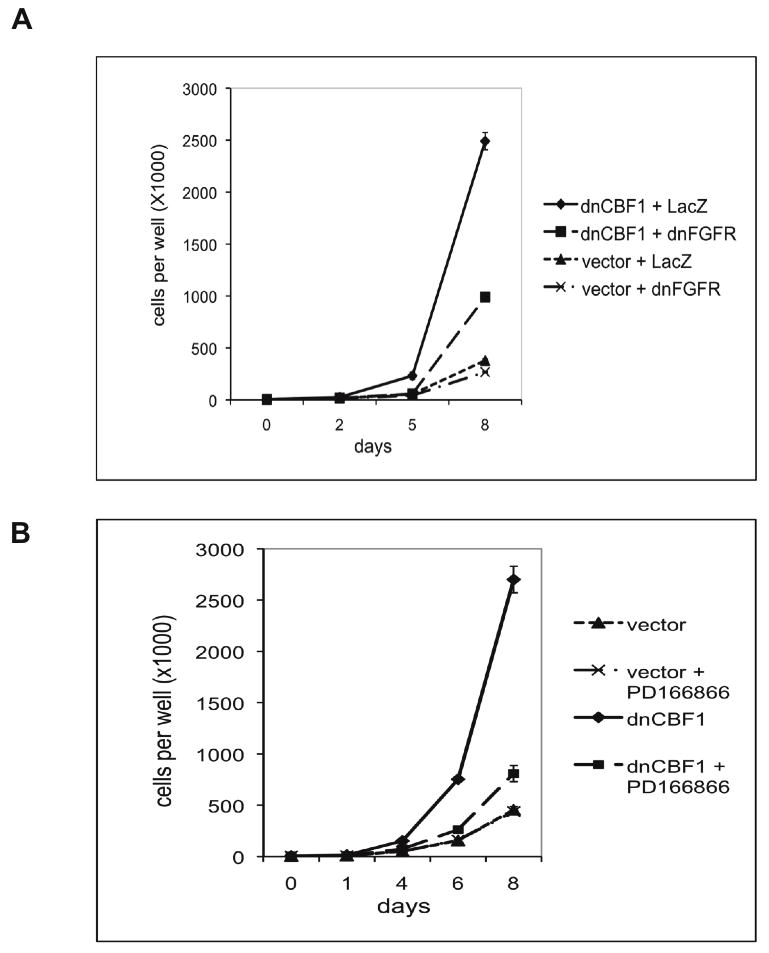

Because dnCBF1 induced both a transformed cell phenotype, and FGF1 expression and release, we next evaluated the role of FGFR signaling in dnCBF1-dependent cell transformation. dnCBF1 transfected cells were transduced with an adenovirus encoding a dominant negative mutant of FGFR1. dnFGFR1 comprised the extracellular and transmembrane domains of FGFR1 but lacked its cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain. The expression of this dnFGFR1 was demonstrated to efficiently and specifically inhibit FGFR signaling (Neilson and Friesel, 1995). Control dnCBF1 cells were adenovirally transduced with LacZ. Immunofluorescence study demonstrated that 24 h after transduction at least 90% of transduced cells expressed dnFGFR1 or LacZ (data not shown). At this time point, cells were plated to study growth rate or colony formation in soft agar. Unlike LacZ, dnFGFR1 expression resulted in the slowing down of the growth rate of dnCBF1 transfected cells to the level of NIH 3T3 cells transfected with the empty vector (Figure 4A). In subsequent experiments, FGF signaling was inhibited by a specific chemical inhibitor of FGFR activity PD166866. Similar to dnFGFR1 transduction, PD166866 treatment decreased the growth rate of dnCBF1 transfected cells to a level characteristic for vector transfected control cells (Figure 4B). At the same time, PD166866 did not interfere with the growth of control cells. dnFGFR1 transduction (Figure 5A,B) and PD166866 treatment (Figure 5C) also resulted in a dramatic reduction of colony formation in soft agar. Collectively, the experiments with dnFGFR1 and PD166866 demonstrate that the transformed phenotype induced by the inhibition of the CBF1-mediated transcription depends on FGFR signaling.

Figure 4. dnCBF1-induced acceleration of cell proliferation depends on FGFR signaling.

A. dnCBF1-or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were adenovirally transduced with dnFGFR1 or LacZ and plated at 5,000 cells per TC12 plate well and incubated. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 2, 5 and 8 after plating. B. dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were plated at 5,000 cells per TC12 plate well and incubated in absence or presence of 1μM of the FGFR-specific inhibitor PD1666866. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 1, 4, 6 and 8 after plating.

Figure 5. dnCBF1 expression results in anchorage-independent growth, which requires FGFR signaling.

A,B. dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were adenovirally transduced with dnFGFR1 or LacZ and plated in 0.3% agar at 1,000 cells per TC6 plate well. Eighteen days after plating, the colonies were stained with p-iodonitrotetrazolium and counted (A). Photographs of stained colonies were taken using an inverted microscope with a 4X objective (B). Bar −2 mm. C. dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were plated in 0.3% agar at 1,000 cells per TC6 plate well and incubated in absence or presence of 1μM of the FGFR-specific inhibitor PD1666866. Eighteen days after plating, the colonies were stained with p-iodonitrotetrazolium and counted.

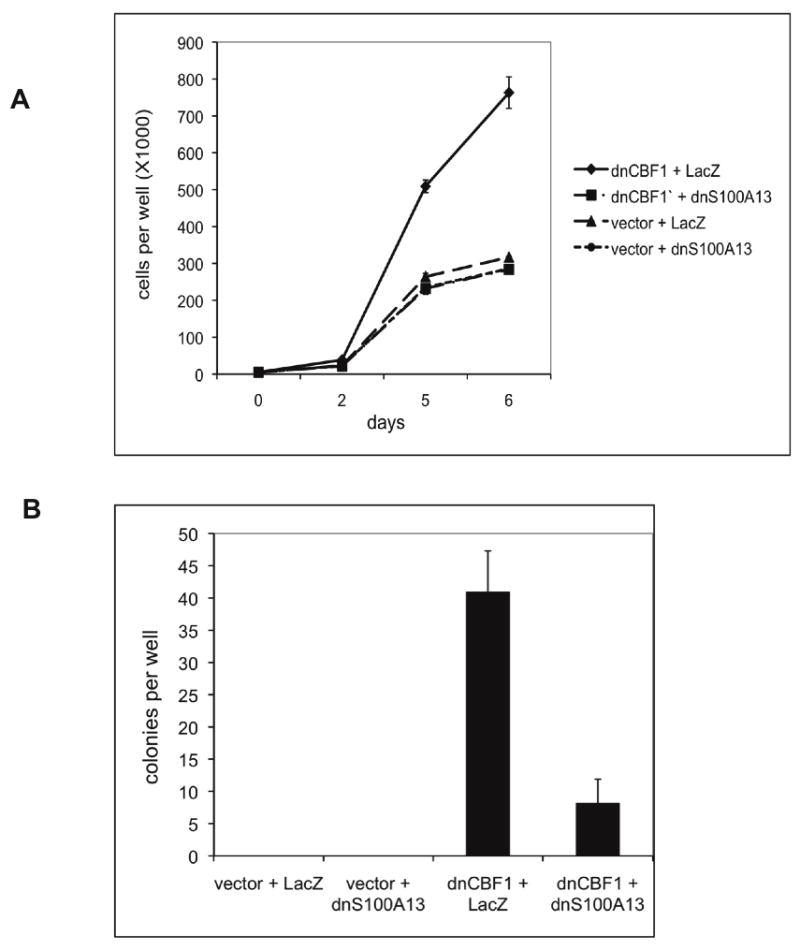

4. S100A13 is critical for transformation of the cells with repressed CBF1-dependent transcription

S100A13 is a critical component of the FGF1 non-classical export complex (Landriscina et al., 2001). To elucidate the role of S100A13 in the transformed phenotype induced by the inhibition of the CBF1-dependent transcription, we explored the effect of a dn form of S100A13 (Landriscina et al., 2001) upon the proliferation rate and growth in soft agar of dnCBF1 transfectant cells. Adenoviral constructs coding for dnS100A13 or for LacZ (control) were used for cell transduction. Immunofluorescence study demonstrated that 24 h after transduction at least 90% of transduced cells expressed dnS100A13 or LacZ (data not shown). Unlike LacZ, the expression of dnS100A13 decreased the growth rate of dnCBF1 to the level of vector transfected NIH 3T3 cells (Figure 6A). Additionally, dnS100A13 drastically inhibited colony formation in soft agar by dnCBF1 cells (Figure 6B). Thus, the in vitro transformed phenotype induced by the inhibition of CBF1-dependent transcription is mediated at least in part by S100A13.

Figure 6. dnS100A13 attenuates the transformed phenotype induced by dnCBF1.

A. dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were adenovirally transduced with dnS100A13 or LacZ and plated at 5,000 cells per TC12 plate well. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 2, 5 and 6 after plating. B. dnCBF1-or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells were adenovirally transduced with dnFGFR1 or LacZ and plated in 0.3% agar at 1,000 cells per TC6 plate well. Eighteen days after plating, the colonies were stained with p- iodonitrotetrazolium and counted.

5. FGF1 export and enhancement of cell proliferation in cells with repressed CBF1-dependent transcription depend on sphingosine kinase 1

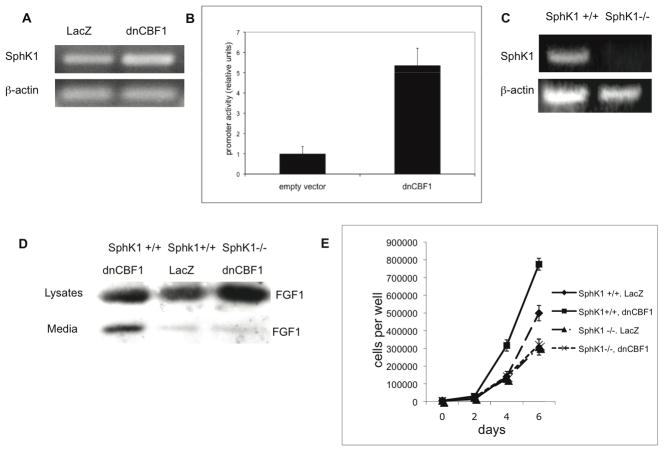

Comparative gene expression analysis using Agilent Whole Muse Genome Oligo Microarrays was applied to further explore mechanisms underlying the induction of FGF1 export in cells with repressed CBF1-dependent transcription. The comparison of gene expression in NIH 3T3 cells adenovirally transduced with dnCBF1 and LacZ (control) revealed that dnCBF1 induced a 4.5 fold increase of the expression of SphK1, a recently identified component of the stress-induced FGF1 export multiprotein complex (Soldi et al., 2007). RT-PCR analysis confirmed a significant increase of SphK1 expression in dnCBF1 transduced cells (Figure 7A). Luciferase assay demonstrated that dnCBF1 enhanced SphK1 promoter activity more than five fold (Figure 7B). We used SphK1 null mouse embryo fibroblasts (Figure 7C) to assess the role of SphK1 in dnCBF1-induced FGF1 export. SphK1 −/− and control SphK1 +/+ cells were adenovirally cotransduced with FGF1 and dnCBF1 or LacZ (control). While dnCBF1 transduction induced FGF1 export in SphK1 +/+ cells, it failed to produce such effect in SphK1 null cells (Figure 7D). In a separate series of experiments, dnCBF1 transduction significantly enhanced the growth of SphK1+/+ cells but not of SphK1 null cells (Figure 7E). Apparently, SphK1 plays an important role in the induction of FGF1 export and cell transformation, which result of the inhibition of CBF1-dependent transcription.

Figure 7.

A,B. Inhibition of CBF1-mediated signaling enhances SphK1 transcription. A. RT-PCR assay of endogenous SphK1 transcription in NIH 3T3 cells adenovirally transduced with LacZ- and dnCBF1. β-actin was used as loading control. B. Luciferase assay of dnCBF1 effect on SphK1 promoter activity in NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were transiently co-transfected with a TK-renilla construct, an SphK1 promoter luciferase reporter construct and either a dnCBF1 or empty vector. Promoter activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent SD. C,D. dnCBF1- induced FGF1 export depends on SphK1. C. RT-PCR assay of SphK1 expression in SphK1−/− and SphK1 +/+ cells. β-actin was used as loading control. D. SphK1−/− and SphK1 +/+ cells were adenovirally cotransduced with FGF1 and either LacZ or dnCBF1. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C in serum-free medium. FGF1 was isolated from the medium using heparin-Sepharose chromatography, and 10% of cell lysate or FGF1 equivalent of the total medium were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using rabbit anti-FGF1 antibodies. E. Stimulation of cell growth by dnCBF1 depends on SphK1. SphK1 −/− and SphK1 +/+ cells were adenoviraly transduced with dnCBF1 or LacZ and plated at 5,000 cells per TC12 plate well. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 2, 4 and 6 after plating.

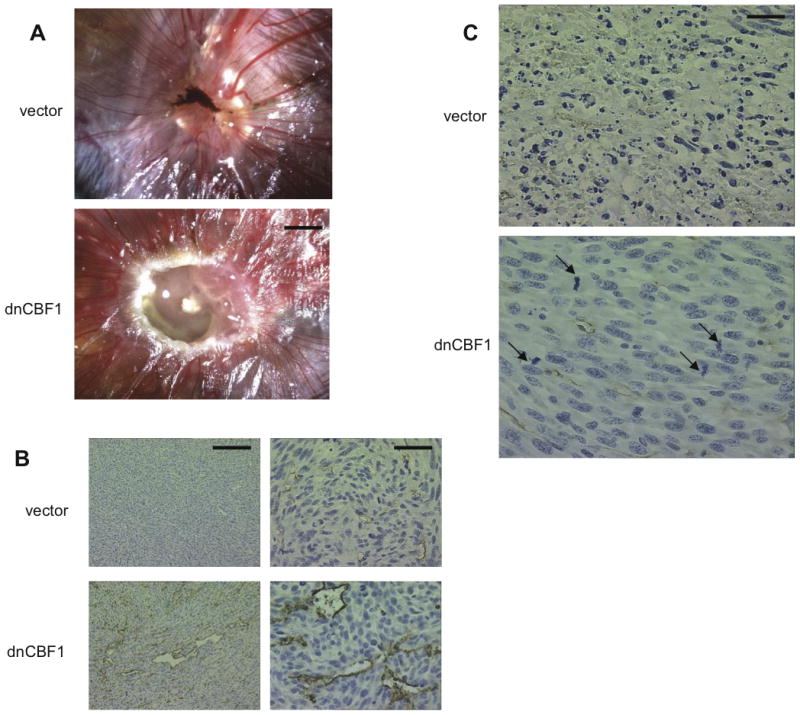

6. Cells with inhibited CBF1-dependent transcription form rapidly growing tumors

The acquisition of the in vitro transformed phenotype by dnCBF1-expressing cells prompted us to evaluate their ability to form tumors in vivo. In the initial series of experiments, we assessed tumor formation in chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model. While, control NIH 3T3 adenovirally transduced with LacZ failed to form tumors on CAM, 80% of chicken embryos injected dnCBF1-transduced NIH 3T3 cells formed distinct tumors (Figure 8A). In the next series of experiments, one-month-old female nude mice were subcutaneously inoculated with dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells. The formation of tumors was monitored by visual observation and palpation. All mice injected with dnCBF1-transfected cells formed 5–8 mm diameter subcutaneous tumors by day 18 after cell injection. In sharp contrast, mice injected with vector-transfected cells formed 5–6 mm diameter tumors only by day 50 after cell injection. At day 18, control cell-injected mice did not display visible signs of tumors. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumors formed by dnCBF1 transfected cells revealed extensive vascularization as detected by PECAM immunostaining, a specific marker of endothelial cells (Figure 8B). These tumors exhibited a large number of mitotic figures reflecting high proliferation level (Figure 8C). Conversely, the tumors formed by control cells displayed few mitotic figures, and their core contained abundant apoptotic cells (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. dnCBF1 transfected cells form rapidly growing tumors in chicken CAM and nude mice.

A. 2×106 dnCBF1- or LacZ-transduced NIH 3T3 cells were placed in a drop of DMEM on top of 10 days old chicken embryo CAMs. Embryos were incubated for additional 7 days and photographs taken. Bar −2 mm. B, C. Nude mice were subcutaneously injected with 2 × 106 dnCBF1- or vector-transfected NIH 3T3 cells. dnCBF1 tumors were extracted at day 18, when all injected mice exhibited visible tumor formation, and control vector-transfected tumors - on day 50, when in two of four mice tumors became visible. B. Tumor sections were immunohistochemically stained for PECAM and counterstained with hematoxylin. Bars 200 μ (left column) and 50 μ (right column). C. Numerous apoptotic bodies in the core of a vector tumor and mitotic figures (marked by arrows) in the core of a dnCBF1 tumor. Bar 25 μ.

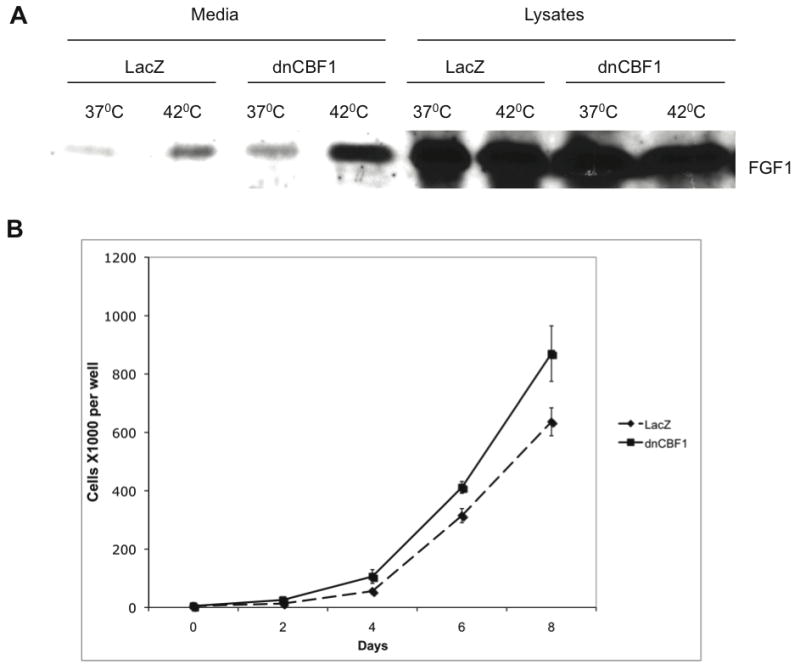

7. dnCBF1 induces the export of endogenous FGF1 from melanoma cells and enhances their proliferation

It was critically important to confirm the role of Notch signaling in the regulation of endogenous FGF1 secretion. To this end, we chose human melanoma A375 cells, which have a high level of FGF1 expression and, as we found, release it under stress conditions (Di Serio et al., 2008). Using melanoma cells was especially significant because our recent collaborative studies demonstrated high levels of expression of S100A13, a critical component of FGF1 export complex, in aggressive human melanomas (Massi et al.). We found that transduction of A375 with dnCBF1 resulted in a strong enhancement of both spontaneous and heat shock-induced export of endogenous FGF1 (Figure 9A). In separate experiments, we found that similar to NIH 3T3 cells, dnCBF1 significantly enhanced the proliferation of A375 cells (Figure 9B).

Figure 9. dnCBF1 expression results in stimulation of endogenous FGF1 release from melanoma cells and enhancement of their growth.

A. A375 melanoma cells were adenovirally transduced with LacZ (control) or dnCBF1. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 or 42°C in serum-free medium. FGF1 was isolated from the media and lysates using heparin-Sepharose chromatography, and FGF1 equivalents of the total media and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using rabbit anti-FGF1 antibodies. B. A375 cells were adenoviraly transduced with dnCBF1 or LacZ and plated at 5,000 cells per TC12 plate well. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 2, 4, 6 and 8 after plating.

8. Role of FGF1 in cell transformation induced by the inhibition of CBF1- dependent transcription

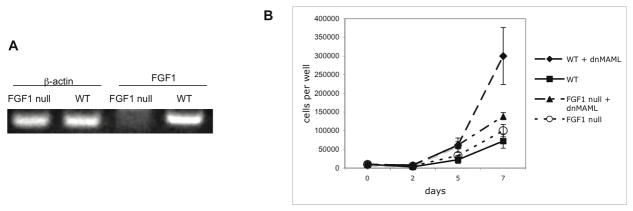

To further explore the role of FGF1 in the transformed phenotype induced by inhibition of Notch signaling, we used spontaneously immortalized osteoblasts derived from FGF1 null mice (Miller et al., 2000) (Figure 10A). These cells were stably transduced with the retroviral construct coding for dnMAML:GFP chimera. Fluorescent cells were selected using flow cytometry. The growth rate of dnMAML transduced cells and non-transduced control cells was assessed. dnMAML transduction resulted in a strong enhancement of the growth rate of wild type osteoblasts (Figure 10B). However, this effect was only barely detectable in FGF1 null cells (Figure 10B).

Figure 10. Differential proliferative effects of dnMAML expression in wild type and FGF1 null osteoblasts.

A. RT-PCR assay of FGF1 expression in FGF1 null and WT osteoblasts. β-actin was used as loading control. B. Retrovirally transduced with dnMAML and control untransduced WT and FGF1 null osteoblasts were plated at 10,000 cells per TC12 plate well. Cells were trypsinized and counted at day 2, 5 and 7 after plating.

Discussion

FGF1 is widely expressed in the tissues of vertebrate organisms (Ornitz and Itoh, 2001). It stimulates such physiologic processes as angiogenesis (Thompson et al., 1988) and neurite outgrowth (Renaud et al., 1996). At the same time, FGF1 is involved in pathologies, such as hereditary hypertension (Tomaszewski et al., 2007), fibrosis (Yu et al., 2003) and certain types of cancer (Kwabi-Addo et al., 2004; Okunieff et al., 2003; Woolley et al., 2000). Nearly ubiquitous expression and various activities of FGF1 imply that the release of this growth factor requires stringent regulation. We found that stress-independent non-classical export of FGF1 is induced when dominant negative forms of transcription factors CBF1 and MAML inhibit the CBF1-dependent Notch signaling. In addition, dnCBF1 and dnMAML induced the transcription of FGF1, as well as SphK1 an important component of the FGF1 export complex. Thus, both the expression and secretion of FGF1 are under the negative control of CBF1-dependent transcription, which is a key downstream element of the Notch signaling pathway (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Negative regulation of FGF1 expression and release by CBF1-mediated Notch signaling (hypothetic model).

CBF1- and MAML-dependent Notch signaling induces the expression of downstream transcriptional repressor(s), which inhibit the expression of FGF1 and SphK1, and FGF1 export.

The cross-talk between Notch signaling and FGF1 could play a role in the regulation of the repair of damaged tissues. Because both Notch receptors and ligands are transmembrane proteins and Notch signaling depends on direct intercellular contacts, tissue damage can result in the inhibition of Notch signaling by disrupting the tissue microenvironment. Indeed, decrease in the level of Notch1ICD and Hes1 expression occurs shortly after wounding of murine corneal epithelium (Djalilian et al., 2008). In turn, the inhibition of Notch signaling can induce the transcription and export of FGF1, which stimulates local cell proliferation and migration, processes critical for wound repair. Additionally, released FGF1 stimulates angiogenesis required for wound healing. Eventually, the process of wound healing results in the re-establishment of cell-cell contacts, a precondition of efficient Notch signaling. Interestingly, FGF1 also stimulates the expression of Notch ligand Jagged 1 (Zimrin et al., 1995). In repaired tissues, the restored Notch signaling could suppress FGF1 transcription and export: a presumptive negative feedback loop.

As demonstrated in this study, cells with inhibited CBF1-dependent transcription acquire a transformed phenotype, which is dependent on FGFR1 signaling and expression of FGF1. In vivo, dnCBF1 transfected cells formed fast growing tumors. This can be explained both by enhanced cell proliferation and FGF1-dependent stimulation of tumor angiogenesis (Figure 11). The effect of Notch signaling upon cell proliferation varies depending on cell type. For example, Notch activation induces malignant transformation of T-lymphocytes (Shih Ie and Wang, 2007). Alternatively, down regulation of Notch signaling results in transformation of keratinocytes (Demehri et al., 2009; Kolev et al., 2008). Mice transgenic for dnMAML form rapidly growing epidermal carcinomas (Proweller et al., 2006). Notch signaling was also demonstrated to inhibit the proliferation of endothelial cells (Liu et al., 2006). The induction of FGF1 expression and export can be a cause of cell transformation in certain cell types where Notch signaling is inhibited. Particularly, we demonstrated that in A375 melanoma cells dnCBF1 stimulates both FGF1 export and proliferation.

It remains to be determined how CBF1-dependent transcription regulates export and expression of FGF1. First, it must be stressed that these are two independent phenomena. Indeed, the reported dnCBF1-induced release of adenovirally transduced FGF1 clearly did not rely on the stimulation of FGF1 transcription. Second, the expression of a large number of genes, primarily transcription factors, is stimulated by CBF1. Most notable among them are transcription repressors of the Hes and Hrt families (Fortini, 2009). However, overexpression of Hrt1 and Hrt2 in dnCBF1-expressing cells did not result in the inhibition of FGF1 export in NIH 3T3 cells transfected with dnCBF1 (data not shown). Also, unlike dnCBF1, dnHes1 failed to induce FGF1 release (data not shown). On the other hand, we found that dnCBF1 enhances the transcription of SphK1, an important component of the FGF1 release pathway. Moreover, stimulating effects of dnCBF1 upon cell proliferation and FGF1 export depend on SphK1. Further experiments with over expression and knockdown of CBF1-regulated genes and studies of binding of their products to the promoters of FGF1 and SphK1 genes should result in the elucidation of specific regulators of FGF1 expression and export.

The reported induction of FGF1 export caused by the inhibition of dnCBF1-dependent transcription raises a question whether the non-classical secretion of other signal peptide-less proteins is under the negative control of Notch signaling. Indeed, although there apparently exists several distinct mechanisms of non-classical protein release (Nickel, 2005; Prudovsky et al., 2008) it has been shown that the export of proteins such as IL1α (Mandinova et al., 2003), epimorphin (Hirai et al., 2007) and prothymosin (Matsunaga and Ueda) exhibit characteristics similar to FGF1. The release of these polypeptides and potentially FGF2, which has the highest degree of homology to FGF1 in the whole FGF family, could also be regulated by Notch signaling.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor 1: NIH; Contract grant numbers: RR15555 (Project 4), R01 HL35627 and R01 HL32348

Contract grant sponsor 2: Maine Cancer Foundation

We are grateful to the RIKEN BRC DNA bank (Tsukuba, Japan) and Dr. T. Honjo (University of Kyoto, Japan) for the generous gift of the dnCBF1 construct. We are also grateful to Drs. W.S. Pear (University of Pennsylvania) and J. Aster (Harvard University) for the generous gift of the dnMAML expression construct. We thank Dr. R. Proia (NIH, Bethesda, MD) for SphK1 knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts and Dr. L. Obeid (University of South Carolina, Charlestone) for the SphK1 luciferase reporter construct. The study has been supported by a Maine Cancer Foundation grant to IP and NIH grants P20 RR15555 to RF (Project 4 – IP), HL35627 to IP and HL32348 to IP. In this work, we used the services of the Flow Cytometry Core and Histopathology Core supported by NIH grant P20 RR181789 (D. Wojchowski, PI), and Protein, Nucleic Acid and Cell Imaging Core, Mouse Transgenic and In Vivo Imaging Core and Recombinant Viral Vector Core supported by grant P20 RR15555 (RF, PI).

Abbreviations

- dn

dominant negative

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

FGF receptor

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- sJg1

soluble Jagged1

- SphK1

sphingosine kinase 1

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. There are no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

References

- Chung CN, Hamaguchi Y, Honjo T, Kawaichi M. Site-directed mutagenesis study on DNA binding regions of the mouse homologue of Suppressor of Hairless, RBP-J kappa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(15):2938–2944. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demehri S, Turkoz A, Kopan R. Epidermal Notch1 loss promotes skin tumorigenesis by impacting the stromal microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Serio C, Doria L, Pellerito S, Prudovsky I, Micucci I, Massi D, Landriscina M, Marchionni N, Masotti G, Tarantini F. The release of fibroblast growth factor-1 from melanoma cells requires copper ions and is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt intracellular signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djalilian AR, Namavari A, Ito A, Balali S, Afshar A, Lavker RM, Yue BY. Down-regulation of Notch signaling during corneal epithelial proliferation. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1041–1049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M, Kolev V, Kacer D, Mouta-Bellum C, Soldi R, Graziani I, Kirov A, Friesel R, Liaw L, Small D, Verdi J, Maciag T, Prudovsky I. Novel cross-talk between three cardiovascular regulators: thrombin cleavage fragment of Jagged1 induces fibroblast growth factor 1 expression and release. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(11):4863–4874. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forough R, Xi Z, MacPhee M, Friedman S, Engleka KA, Sayers T, Wiltrout RH, Maciag T. Differential transforming abilities of non-secreted and secreted forms of human fibroblast growth factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(4):2960–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16(5):633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley T. Notch signaling in vascular development and physiology. Development. 2007;134(15):2709–2718. doi: 10.1242/dev.004184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon L, Avila JL, Demarest RM, Troutman S, Allen M, Ratti F, Rustgi AK, Stanger BZ, Radtke F, Adsay V, Long F, Capobianco AJ, Kissil JL. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in a model of K-ras-induced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 70(11):4280–4286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Kitamura M, Harris-Stansil T, Dai Y, Phipps ML. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J Virol. 1997;71(3):1842–1849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1842-1849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai Y, Nelson CM, Yamazaki K, Takebe K, Przybylo J, Madden B, Radisky DC. Non-classical export of epimorphin and its adhesion to {alpha}v-integrin in regulation of epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 12):2032–2043. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Friedman S, Zhan X, Engleka KA, Forough R, Maciag T. Heat shock induces the release of fibroblast factor 1 from NIH 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10691–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M. Networking of WNT, FGF, Notch, BMP, and Hedgehog signaling pathways during carcinogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolev V, Mandinova A, Guinea-Viniegra J, Hu B, Lefort K, Lambertini C, Neel V, Dummer R, Wagner EF, Dotto GP. EGFR signalling as a negative regulator of Notch1 gene transcription and function in proliferating keratinocytes and cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(8):902–911. doi: 10.1038/ncb1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwabi-Addo B, Ozen M, Ittmann M. The role of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11(4):709–724. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landriscina M, Soldi R, Bagala C, Micucci I, Bellum S, Tarantini F, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. S100A13 participates in the release of fibroblast growth factor 1 in response to heat shock in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):22544–22552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVallee TM, Tarantini F, Gamble S, Carreira CM, Jackson A, Maciag T. Synaptotagmin-1 is required for fibroblast growth factor-1 release. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(35):22217–22223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong KG, Karsan A. Recent insights into the role of Notch signaling in tumorigenesis. Blood. 2006;107(6):2223–2233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZJ, Xiao M, Balint K, Soma A, Pinnix CC, Capobianco AJ, Velazquez OC, Herlyn M. Inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation by Notch1 signaling is mediated by repressing MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways and requires MAML1. Faseb J. 2006;20(7):1009–1011. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4880fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandinova A, Soldi R, Graziani I, Bagala C, Bellum S, Landriscina M, Tarantini F, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. S100A13 mediates the copper-dependent stress-induced release of IL-1{alpha} from both human U937 and murine NIH 3T3 cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 13):2687–2696. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi D, Landriscina M, Piscazzi A, Cosci E, Kirov A, Paglierani M, Di Serio C, Mourmouras V, Fumagalli S, Biagioli M, Prudovsky I, Miracco C, Santucci M, Marchionni N, Tarantini F. S100A13 is a new angiogenic marker in human melanoma. Mod Pathol. 23(6):804–813. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga H, Ueda H. Stress-induced non-vesicular release of prothymosin-alpha initiated by an interaction with S100A13, and its blockade by caspase-3 cleavage. Cell Death Differ. 17(11):1760–1772. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL, Ortega S, Bashayan O, Basch R, Basilico C. Compensation by fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) does not account for the mild phenotypic defects observed in FGF2 null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(6):2260–2268. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2260-2268.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson KM, Friesel RE. Constitutive activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 by a point mutation associated with Crouzon syndrome. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(44):26037–26040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel W. Unconventional secretory routes: direct protein export across the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Traffic. 2005;6(8):607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel W, Rabouille C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(2):148–155. doi: 10.1038/nrm2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofziger D, Miyamoto A, Lyons KM, Weinmaster G. Notch signaling imposes two distinct blocks in the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Development. 1999;126:1689–1702. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okunieff P, Fenton BM, Zhang L, Kern FG, Wu T, Greg JR, Ding I. Fibroblast growth factors (FGFS) increase breast tumor growth rate, metastases, blood flow, and oxygenation without significant change in vascular density. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;530:593–601. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, Itoh N. Fibroblast growth factors. Genome Biol. 2001;2(3) doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-3-reviews3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perumalsamy LR, Nagala M, Sarin A. Notch-activated signaling cascade interacts with mitochondrial remodeling proteins to regulate cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107(15):6882–6887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta M, Dell’Era P, Mitola S, Moroni E, Ronca R, Rusnati M. Fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):159–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proweller A, Tu L, Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Lu MM, Seykora J, Millar SE, Pear WS, Parmacek MS. Impaired notch signaling promotes de novo squamous cell carcinoma formation. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7438–7444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudovsky I, Tarantini F, Landriscina M, Neivandt D, Soldi R, Kirov A, Small D, Kathir KM, Rajalingam D, Kumar TK. Secretion without Golgi. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(5):1327–1343. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud F, Desset S, Oliver L, Gimenez-Gallego G, Van Obberghen E, Courtois Y, Laurent M. The neurotrophic activity of fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) depends on endogenous FGF1 expression and is independent of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(5):2801–2811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlgren C, Lendahl U. Notch signaling and its integration with other signaling mechanisms. Regen Med. 2006;1(2):195–205. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanalkumar R, Dhanesh SB, James J. Non-canonical activation of Notch signaling/target genes in vertebrates. Cell Mol Life Sci. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0391-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanalkumar R, Indulekha CL, Divya TS, Divya MS, Anto RJ, Vinod B, Vidyanand S, Jagatha B, Venugopal S, James J. ATF2 maintains a subset of neural progenitors through CBF1/Notch independent Hes-1 expression and synergistically activates the expression of Hes-1 in Notch-dependent neural progenitors. J Neurochem. 113(4):807–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Ie M, Wang TL. Notch signaling, gamma-secretase inhibitors, and cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67(5):1879–1882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small D, Kovalenko D, Kacer D, Liaw L, Landriscina M, Di Serio C, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. Soluble Jagged 1 represses the function of its transmembrane form to induce the formation of the Src-dependent chord-like phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):32022–32030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small D, Kovalenko D, Soldi R, Mandinova A, Kolev V, Trifonova R, Bagala C, Kacer D, Battelli C, Liaw L, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. Notch activation suppresses fibroblast growth factor-dependent cellular transformation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(18):16405–16413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldi R, Mandinova A, Venkataraman K, Hla T, Vadas M, Pitson S, Duarte M, Graziani I, Kolev V, Kacer D, Kirov A, Maciag T, Prudovsky I. Sphingosine kinase 1 is a critical component of the copper-dependent FGF1 export pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(15):3308–3318. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Anderson KD, DiPietro JM, Zwiebel JA, Zametta M, Anderson WF, Maciag T. Site-directed neovessel formation in vivo. Science. 1988;241(4871):1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.2457952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski M, Charchar FJ, Lynch MD, Padmanabhan S, Wang WY, Miller WH, Grzeszczak W, Maric C, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Dominiczak AF. Fibroblast growth factor 1 gene and hypertension: from the quantitative trait locus to positional analysis. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1915–1924. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley PV, Gollin SM, Riskalla W, Finkelstein S, Stefanik DF, Riskalla L, Swaney WP, Weisenthal L, McKenna RJ., Jr Cytogenetics, immunostaining for fibroblast growth factors, p53 sequencing, and clinical features of two cases of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Mol Diagn. 2000;5(3):179–190. doi: 10.1054/modi.2000.9405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Wang F, Jin C, Huang X, Miller DL, Basilico C, McKeehan WL. Role of fibroblast growth factor type 1 and 2 in carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury and fibrogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(4):1653–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63522-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimrin AB, Villeponteau B, Maciag T. Models of in vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell differentiation on fibrin but not matrigel is transcriptionally dependent. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213(2):630–638. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]