Abstract

Serial forced displacement has been defined as the repetitive, coercive upheaval of groups. In this essay, we examine the history of serial forced displacement in American cities due to federal, state, and local government policies. We propose that serial forced displacement sets up a dynamic process that includes an increase in interpersonal and structural violence, an inability to react in a timely fashion to patterns of threat or opportunity, and a cycle of fragmentation as a result of the first two. We present the history of the policies as they affected one urban neighborhood, Pittsburgh’s Hill District. We conclude by examining ways in which this problematic process might be addressed.

Keywords: Serial forced displacement, Segregation, Redlining, Urban renewal, Planned shrinkage, HOPE VI, Gentrification, Foreclosure, Community disintegration

Introduction

As students of the effects of urban policy on health, we found ourselves in a major debate. One of us1 had studied the links between planned shrinkage and the AIDS epidemic, while the other2 had examined urban renewal and mental health, and we debated which had had more dire consequences for the health of people of color and poor people. During fieldwork in 2001, Fullilove’s team visited five US cities to learn the history of urban renewal. The team documented that communities that had been displaced by urban renewal had also experienced planned shrinkage. Furthermore, the team noted, those communities were facing yet another episode of displacement due to HOPE VI.3 We were surprised by the repeated experience of upheaval. On investigation, we became convinced that the cumulative effects of the series of displacements needed to be considered to understand the current states of health and social organization in US communities. The purpose of this paper is to list the critical set of policies that compose serial displacement, describe the key consequences of repeated displacement, provide a case study of serial displacement in one neighborhood, and propose an agenda of reform.

The Policies That Compose the Series

The dominant policies we have identified are segregation, redlining, urban renewal, planned shrinkage/catastrophic disinvestment, deindustrialization, mass criminalization, gentrification, HOPE VI, and the foreclosure crisis. Other processes could be added. The crack epidemic, for example, was a powerful disorganizing force. It seems, however, that the main harm from the crack epidemic was due to excessive criminal penalties attached to use and sales and the lack of adequate prevention and treatment.4,5 Hence, we believe that the effects of crack are captured by including mass criminalization in the list. Another example is disaster, which causes upheaval and has effects similar to those of urban renewal. Therefore, disaster could, and should, be included in the series in cities like New Orleans where it has occurred. We recognize that similar arguments could be made about a number of other policies and processes that are not included on this list, and this list represents somewhat arbitrary choices on our part. Thus, our list is a starting point for discussion of the concept we are proposing here.

Segregation is an important feature of American urban life. As Thomas Hanchett has documented in his book, Sorting Out the New South City,6 people of different races and classes were intermingled in American cities 150 years ago. The policies of separation were instituted gradually, but inexorably, leading to a radical separation by both race and class, what Massey and Denton later called “American Apartheid.”7 Such separation continues to be a feature of American life, at this point, most prominent in the organization of residential areas.

Redlining, instituted by the federal government’s Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1937, was designed to steer investment away from risky places. These were defined as those places with older buildings and non-white residents. Literally, the presence of a single Negro family meant that an area was given the worst possible rating, thus setting up the material basis for white flight. Hanchett observed, “The handsomely printed map with its sharp-edged boundaries made the practice of deciding credit risk on the basis of neighborhood seem objective and put the weight of the U.S. government behind it…”

As to the effects in Charlotte, Hanchett found:

…the HOLC survey influenced investment practices for decades. The map froze patterns of the mid-1930s and objectified borderlines between areas, with sometimes odd effects. Dilworth proved a striking example. The survey sliced the suburb into three areas… Dilworth Road East in the A section, for instance, remained a very desirable middle-class area in the 1970s. Kingston Avenue two blocks away in the B section, just a bit more built-up in 1937, became a mix of rental and owner-occupied dwellings during the same period. Park Avenue, one block parallel to Kingston and lined with exactly the same kind of houses, happened to fall within the C section on the HOLC map. It became entirely rental and was allowed to run down, and many of its houses were demolished by the 1970s. (p. 213)

Urban renewal refers to the program instituted under the federal Housing Act of 1949.8 That act authorized the seizing of land, using the powers of eminent domain, in areas deemed “blighted.” These areas were cleared and the land sold at reduced prices to developers for new, “higher” uses. Large areas of land were cleared and the land was used for cultural centers, universities, housing projects, and other developments. Approximately one million people were displaced in 2,500 projects carried out in 993 American cities; 75% of those displaced were people of color.

Planned shrinkage was a policy of concentrating population in some areas of the city, while withdrawing public and private resources from abandoned areas. This is a catastrophic form of disinvestment, as it lowers investment below the level required for urban sustainability. The best-known application of this policy was in New York City in the 1970s, when its institution precipitated the burning of minority neighborhoods by closing selected fire stations. Wallace has studied the health and social consequences and found that planned shrinkage dispersed the poor to circumjacent neighborhoods, broke social networks, destroyed nascent political organization, and spread diseases and violence throughout the New York metropolitan area.9 Because of New York’s supreme position in the interrelationship of the world’s cities—the international urban hierarchy—the collapse of health in that metropolitan area has had international repercussions.

Deindustrialization—the undoing of American industrial development which dates back to the colonial era—followed the inability of American industry to remain competitive.10 This has been attributed to the Cold War, which siphoned the best engineers and the most investment into weapons-related research and development, ultimately to the peril of the whole industrial system.11 The United States has more recently begun what we call “decollarization,” the exporting of white collar/service jobs, which threatens to remove the last leg from the three-legged stool of employment: agriculture, industry, and service/technical.

Mass criminalization is related to the collapse of manufacturing jobs in the following manner. With the collapse of industry as a source of employment, alternative employment emerged, including a major industry of drug dealing. Drug dealing was linked to an increase in addiction, violence, and the spread of infectious disease. The explosion of violence that accompanied the crack–cocaine epidemic triggered an avalanche of harsh policies that put many Americans behind bars. The criminalization of African American men has been particularly pervasive and deleterious.12,13

Gentrification, the replacement of lower income residents with more wealthy ones, has gathered speed in cities across the United States.14 Gentrification is often viewed as a “natural” process, rather like the tides, but the study of serial displacement makes it clear that this process is itself eased by pro-gentry policies and built on the destruction of the prior inhabitants’ communities by the series of policies noted above.15

HOPE VI was enacted by the federal government in 1992. Directed at “distressed” housing communities, the program offered money to cities to redo existing public housing as mixed-income housing. Although it was advertised as solving a problem of hyperconcentration of the poor, many HOPE VI projects simply moved the poor to new areas of concentrated poverty. Sometimes, those areas were outside city limits, in nearby suburbs.16

The foreclosure crisis that began in 2000 has affected many cities in the United States. It has fallen hardest on people of color.17 As a result of deregulation of banking, there was a marked increase in “subprime” loans, those made to people with marginal credit, the group with the highest foreclosure rates. Black and Hispanic homeowners have lost their investments and have been forced to move. The neighborhoods affected are part of the system of displacement, but often one ring out from the areas involved in urban renewal and planned shrinkage. The foreclosure crisis has undermined neighborhood functioning.

The Consequences of Serial Forced Displacement

At present, a persistent policy of serial forced displacement of African Americans has created a persistent de facto internal refugee population that expresses characteristic behavioral and health patterns. These include raised levels of violence, family disintegration, substance abuse, sexually transmitted disease, and so on. These harms are evidently a result of the cumulative effects—including high levels of stress—of multiple displacements.

A stage-state model of social disintegration was proposed to describe what happens to communities affected by such a series of policies.18 The stage-state model is based on the work of Alexander Leighton, who posited that communities exist in a continuum from integration to disintegration.19 He defined integration as internal interconnection, characterized by mutual support. He placed disintegration at the other end of the continuum of social organization and characterized it as individualism. The stage-state model hypothesized that communities that suffered from a series of negative events would exhibit partial collapse after each. In the absence of adequate mitigation, this meant that the collapse was a downhill progression from integration towards disintegration, punctuated by changes in the state of social relationships.

Beverly Watkins carried out a study of Harlem, a community known to have suffered from a series of harmful policies.20 She found that the community did indeed show evidence of increasing dysfunction after each negative event. As predicted by Leighton, families fragmented, social organization declined, and disease increased. Violent behavior emerged as a new behavioral language adopted for communication in the context of the “noisy” channel of social disintegration.21

Serial displacement directed at a minority neighborhood wreaks havoc on the surrounding areas. Wallace showed how planned shrinkage policies of fire service withdrawal shotgunned AIDS over the Bronx section of New York, expanding the focus of infection from what would have been a small nexus of intravenous drug users concentrated in the old “South Bronx” to a borough-scale phenomenon that reflected the intersection of social networks fragmented by forced displacement that would have otherwise remained distinct.9

On the national scale, Wallace and Wallace found that economic displacement—deindustrialization/rustbelt—for which African Americans were “last hired, first fired,” served as a powerful impetus for the national diffusion of AIDS.1

More recent work implicates the psychosocial stresses of both forced migration and deindustrialization in the US obesity epidemic.22 African American death rates of obesity-related disorders such as diabetes and hypertension range from a quarter to half again the rate for White Americans, a circumstance attributable to the policy-driven concentration and persistence of psychosocial stress in that population associated with serial displacement.

Empirical studies by Barker and colleagues suggest that these effects will persist across generations due to epigenetic effects.23 It is increasingly clear that, to interrupt these effects, it is not enough to reduce stress on a pregnant mother. It is necessary to have reduced stress on her mother, and her grandmothers before her, as effects may persist across three generations.

This suggests that the effects of policy-driven forced economic and spatial displacement of African Americans will remain with us for some considerable time, and will not be ameliorated by programs that further displace affected populations in the name of “ending the culture of poverty.” Ending serial forced displacement will, in time, end those patterns. The “culture of poverty” is the effect of an imbalance in the power relations between groups which is, after all, an outfall of an embedding culture of apartheid that enmeshes us all.24

A Brief Examination of Serial Forced Displacement in One Neighborhood

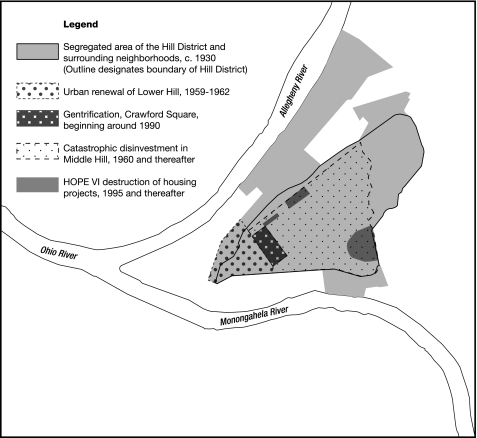

The Hill District in Pittsburgh, PA, was settled by immigrants from Eastern Europe who arrived to work in the area’s steel industry.3 African Americans were among the first settlers of the area, but were a distinct minority until the First World War. The large wave of immigration from the South during the Great Migration increased the numbers of African Americans. They were forced to live in distinct sections of Pittsburgh, creating the large urban ghetto of the Hill District, among others25 (See Figure 1). Redlining, which mapped over segregation, effectively shut off new investment in areas like the Hill District.

Figure 1.

Serial displacement in Pittsburgh's Hill District.

Living under these oppressive conditions, but united in their neighborhood, African Americans organized themselves politically and socially and built a strong community composed of many organizations.26 The area grew in political strength and began to have sufficient political power to challenge the white-only political rule in the city. During this period, residents remembered living in close proximity to neighborhoods, all suffering the same indignities of aging housing and the same pleasures of the neighborhood. Eva-Maria Simms, who interviewed people about their memories of childhood, detailed the strong net of relationships that anchored the young.27 She considered this era, from 1930 to 1960, to be characterized by the quote, “You thought it was just your little world.” Simms noted,

Their “little block” became the anchor for venturing into and understanding the larger world. “We knew each other, the neighbors knew us, they’d look out for us, it’s much different than it is now…we weren’t afraid of anything” (Willa). (p. 78)

After World War II, business and civic leaders organized a plan for urban renewal that targeted the Hill District. Calling the area “blighted,” they cleared more than a hundred acres of land and displaced thousands of people for a cultural campus that was never fully realized: the city did build an arena used originally for light opera and later ice hockey. The displaced people were moved into housing projects, other parts of the Hill District, and other segregated neighborhoods. The urban renewal cut the Hill District off from the rest of city by eliminating roads and public transit and installing a major highway between the neighborhood and downtown.

By this time, in the 1960s, deindustrialization had begun to gather momentum. Pittsburgh is among those rust belt cities that lost most of its industry in a very short period of time. The loss of the steel mills that had drawn African Americans and other unskilled people to the city reverberated through every aspect of the city’s life. The greatest burden was that thousands of unemployed black workers lacked the skills to enter the new economy of health care and education that began to take shape. Chronic unemployment became a permanent feature of life in the Hill. In the absence of legitimate opportunity, drugs and violence flourished.28 Mass criminalization followed and added another form of displacement and social rupture to the growing list.

Simms found that memories of childhood related by people growing up in the period between 1960-1980—an era denoted by the quote, “There was no clear path…”—differed from those of people growing up before urban renewal. The structure of the community had altered. Dense, interconnected, neighborhood-wide networks that shared responsibility for rearing children had been replaced by a more patchwork system of extended families and some neighbors sharing responsibilities for their own. One respondent told Simms,

You mean was it a community? Yeah. But it was changing…On the one hand, certain people could correct me. But on the other hand the people on the second floor had no say-so at all. Because we didn’t know them all that well. People were moving in and out, so it was hard to really get to know people well. So it was only the older people in the community that was really the correctors. (p. 80)

A period of disinvestment followed urban renewal and deindustrialization. Gradually, businesses and other institutions pulled out of the Hill, and it was left to molder. A substantial proportion of the houses were lost because of lack of maintenance and poor civic services. People who had moved to those houses as a result of urban renewal were forced to move again, and many had to leave the Hill as the housing stock collapsed and social disorder increased. The Hill came to be known as a dangerous place, causing most Pittsburghers to stay away. The population of the Hill declined dramatically, falling to 9,830 in 1990 from 38,100 in 1950.29

In the late 1980s, a new development, called Crawford Square, was built at the edge of the neighborhood closest to the arena. High rents made it impossible for the poor left on the Hill to rent there, nor could many people who had had to move away afford to come back. Thus, it became the home of newcomers who were emotionally linked to downtown, not the historic Hill. This was followed by HOPE VI developments that razed public housing projects to build mixed-income housing. People who had moved to the housing projects as a result of earlier displacements were forced to move again. Many moved out of the area, some out of the city of Pittsburgh.

Simms identified the period 1980–2004 as a third era, its character captured in the quote, “It’s crazy now in this world.” The “village” of earlier decades was now limited to extended families, and Simms noted that many families had contracted so that only the single mother was responsible for raising the children. Uncertainty had given way to a sense of danger. Simms reported,

Darien created a powerful neologism to characterize the mood that permeated his teenage years: unexpectancy. He said, “In general, you never know what might happen, you know, in the hood, just you coming out that door, just to see what’s outside, could be a ‘surprise’ everyday. Unexpectancy…You know, you never knows what lies around what corner, but you just gotta be able to be prepared and just hope, you know, you know as they say look both ways before you cross the street, so. That’s basically how it is here. Just look both ways.” (p. 82)

Simms summed up the differences as follows:

| Situatedness | Relationship to adults | Racism and poverty | |

| First Era, 1930–60 | Sense of familiarity and belonging | Large social structure of care and authority | At the edge of awareness |

| Second Era, 1960–80 | Many have moved, more strangers, families draw in to protect children | Smaller structure, but oversight exerted by elders | People sense difference |

| Third Era, 1980–2004 | Single-parent families struggle in isolation | Small circle of adults: “Everybody’s for their self” | Tension between class and ethnic groups |

It is important to note that these policies—segregation, redlining, urban renewal, deindustrialization, planned shrinkage/catastrophic disinvestment, HOPE VI, and gentrification—were all contested by the residents of the Hill. They have drawn on their proud history to demand that the neighborhood be restored and to insist on the right of African Americans to be a part of the Hill going into the future. In 2007, a set of proposals to introduce gambling at the arena triggered a movement that quickly evolved into a campaign for a community benefits agreement. A coalition of 100 organizations joined together as the “One Hill Coalition” with a united set of demands they presented to the city, county, and the Pittsburgh Penguins, the occupants of the arena. In 2008, the struggle of the One Hill Coalition resulted in a historic community benefits agreement, designed to rectify some of the harms dating back to the era of urban renewal.30 The creation of such a large coalition of many organizations—ranging from community development groups to environmental organizations—is a guide for the development of the power needed to end serial displacement.31

What Can We Do about it?

Fullilove examined efforts by clergy to rebuild the Bradhurst neighborhood of Harlem.32 The clergy restored abandoned buildings using various government programs to create social housing where the rents were within the reach of the poor. Our data showed that that restoration of functioning activated positive social interactions. For example, the restoration of businesses at one street corner led to increased movement and increased safety. The return of the public space to good order, in turn, facilitated market-rate investment, whose rents were far out of reach of the average Harlem resident. The well-to-do spent their time shopping and socializing in places the poor could not afford. As result, the emerging social organization was that the rich and the poor were organizing into two separate, mutually suspicious groups.

The resolution of the problems created by serial displacement involves interventions in the economic, social, and physical sectors of the urban environment. This includes a focus on the fundamental civil and human rights that every individual possesses. It must include special attention to the needs of the most vulnerable. For a conference on AIDS in New York City,33 Rodrick and Deborah Wallace proposed the following solutions to address this complex agenda:

Help every family to be strong

End forced displacement of minority communities

Bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States

Rebuild community networks in devastated neighborhoods

Rebuild low-income housing

End mass criminalization of minority and poor people

Enforce anti-discrimination laws

Such a broad agenda can only be carried out by a strong coalition of many interested civic, social, religious, environmental, ecological, and education groups. Coalitions join together because of their common interest. We believe that a clear understanding of the devastating effects of serial forced displacement can form the basis for very broad coalitions, directed at stabilizing American cities and creating a strong basis for health.

References

- 1.Wallace D, Wallace R. A Plague on Your Houses: How New York Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled. London, England: Verso; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fullilove MT. Root shock: the consequences of African American dispossession. J Urban Health. 2001;78:72–80. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fullilove MT. Root shock: how tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America and what we can do about it. New York: Ballantine Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fryer RG, Heaton, Levitt SD, Murphy KM. Measuring the Impact of Crack Cocaine. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2005. Working Paper No. 11318.

- 5.Watkins BX, Fullilove MT. The crack epidemic and the failure of epidemic response. Temple Political Civil Rights Law Rev. 2001; 10(2): 371.

- 6.Hanchett TW. Sorting out the new south city: race, class, and urban development in Charlotte, 1875–1975. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss MA. The origins and legacy of urban renewal. In: Mitchell JP, editor. Federal Housing Policy and Programs: Past and Present. New Brunswick: Rutgers University; 1985. pp. 253–276. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace R. A synergism of plagues: “planned shrinkage,” contagious housing destruction, and AIDS in the Bronx. Environ Res. 1988;47:1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0013-9351(88)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry B, Bennett H. The Deindustrialization of America: Plant Closings, Community Abandonment, and the Dismantling of Basic Industry. NY: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace R, Ullmann J, Wallace D, Andrews H. Deindustrialization, inner city decay, and the hierarchical diffusion of AIDS in the US. Environ Plan A. 1999;31:113–139. doi: 10.1068/a310113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauer M. Rush to Incarcerate: The Sentencing Project. New York: The New Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane SD. Why Are Our Babies Dying? Pregnancy, Birth and Death in America. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lees L, Slater T, Wyly E. Gentrification. NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell JA, Spencer ML. Giving them the old “one-two”: gentrification and the K.O. of impoverished urban dwellers of color. Howard Law Rev. 2003; 46: 433–490.

- 16.Hyra DS. The New Urban Renewal: The Economic Transformation of Harlem and Bronzeville. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez J. Redlining revisited: mortgage lending patterns in Sacramento 1930–2004. Int J Urban Reg Res. 2009;33:291–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00873.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fullilove MT. AIDS and social context. Chapter in AIDS-related Cancers and Their Treatment. Eds. Feigal EG, Biggar R, Levine A. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2000: 371–385.

- 19.Leighton AH. My Name is Legion: Foundations for a Theory of Man in Relation to Culture. New York: Basic Books, Inc.; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins BX. Fantasy, Decay, Abandonment, Defeat, and Disease: Community Disintegration in Central Harlem 1960–1990. New York, NY: Columbia University; 2000.

- 21.Wallace R, Fullilove MT, Flisher AJ. AIDS, violence and behavioral coding: information theory, risk behavior and dynamic process on core-group sociogeographic networks. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:339–352. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace R, Wallace D. Gene Expression and Its Discontents: The Social Production of Chronic Disease. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barker D, Forsen T, Uutela A, Osmond C, Erikson J. Size at birth and resilience to effects of poor living conditions in adult life: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2002;323:1261–1262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7324.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Memmi A. The Colonizer and the Colonized. Boston: Beacon; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darden JT. Afro-Americans in Pittsburgh: The Residential Segregation of a People. Lexington, Massachusetts: D.C. Health and Company; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trotter JW, Day JN. Race and renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh since World War II. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simms EM. Children’s lived spaces in the inner city: historical and political aspects of the psychology of place. Humanistic Psychol. 2008;36:72–89. doi: 10.1080/08873260701828888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acker CJ. How crack found a niche in the American ghetto: the historical epidemiology of drug-related harm. BioSocieties. 2010;5:70–88. doi: 10.1057/biosoc.2009.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubove R. Twentieth Century Pittsburgh: The Post Steel Era. Pittsburgh: The University of Pittsburgh Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belko M. Hill District leaders see a new beginning as arena agreement is signed. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/08233/905581-53.stm. Accessed January 6, 2011.

- 31.Thompson E, Thompson M. Homeboy Came to Orange: a Story of People's Power. Newark, NJ: Bridgebuilder Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fullilove MT, Green Lesley L, Fullilove Robert E. Building momentum: an ethnographic study of inner-city redevelopment. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:840–844. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.6.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace, R. How to Overcome Neighborhood Marginalization. Paper presented at New York Stop AIDS Conference, March 23, 2006. New York City, New York.