Abstract

Community displacing events, natural or human made, are increasing in frequency. By the end of 2009, over 36 million people were known to be displaced worldwide. Displacement is a traumatic experience with significant short- and long-term health consequences. The losses and costs associated with displacement—social connections, employment, property, and economic capital—are felt not only by the displaced individuals but also the communities they have left behind, and the communities that receive displaced individuals. Many researchers have explored the link between health and reduced social, cultural, and economic capital. Most of the displacement literature focuses on the effect of displacement on the displaced individual; however, many families move as a group. In this study, we examined the family process of managing displacement and its associated capital losses by conducting interviews with 20 families. We found that families undergo a four-phase process of displacement: antecedent, uprooting, transition, and resettlement. The losses families experience impact the health and well-being of individuals, families, and communities. The degree to which the displacement process ends successfully, or ends at all, can be affected by efforts to both create connections within the new communities and rebuild economic and social capital.

Keywords: Displacement, Upheaval, Family process, Refugee, Uproot, Capital

Introduction

As the number of events displacing communities, including political and social civil unrest, armed conflict, and natural disaster, increase, the ties that make communities function are demolished almost daily. Globally, 36.5 million people had been displaced at the end of 2009.1 Hurricanes Katrina and Rita displaced 500,000 people in 2005, many of whom are still not completely resettled.2 The 2010 earthquake in Haiti left more than 1,000,000 people homeless.3 While at least 160,000 people are living in temporary shelters,4 the total displacement impact of the 2011 earthquakes and tsunami in Japan is not yet known.

Individuals who are forced out of their community are psychologically injured and experience various kinds of personal and collective losses.5 These massive intra- and interpersonal losses set off complex processes that may not only give rise to new diseases, but also affect how old and new diseases are propagated.6–16 An ecological study by Wallace17 provides an illustrative example. In the 1970s, the destruction of low-income housing in poverty-stricken areas of the South Bronx in New York City led to a massive movement of residents into adjacent neighborhoods, which was followed by a sudden increase in the number and type of diseases in those areas. Major public health problems included crack addiction, crime, HIV infection, and tuberculosis, which spread rapidly throughout the overcrowded receiving communities (i.e., the communities in which the displaced families settled), the larger city, and the region.17

Included in the harms wrought by displacement is the loss of social, cultural, and economic capital.18–27 Social capital refers to such features of social relations as reciprocal expectations, trustworthiness, and effective norms and sanctions. Specifically, social capital embodies a set of resources that reside in the interactions among individuals; conceptually, it is more powerful than social networks or social connections, in that it has tradable value.27,28 Cultural capital encompasses shared language, traditions, and systems of beliefs and values that are used by members of a group to ascribe meanings to events and experiences, to define roles and their distribution among members of given social groups, and to set norms for social interactions.29 Economic capital consists of financial means and economic opportunities, including material resources. Economic capital can be seen as a public good belonging to group members and subject to formal and informal group rules and norms. The three forms of capital—social, cultural, and economic—enable members of a social group to act together and achieve otherwise unattainable outcomes. Because social capital exists only in the relationships among individuals within physical and social structures, the severance of social ties inherent in displacement inevitably impacts on the extent of social capital and hence cultural and economic capital.30,31

Most of the displacement literature focuses on the effect of displacement on the individual; however, many families choose to move as a group or are encouraged to do so by immigration regulations.32 In this study, we looked at the process of displacement and the associated capital losses through the experience of families.

Methods

Study Sample and Data Collection Twenty families were recruited for this study. Family referred to the group of individuals who were displaced together and was defined by participants. Study selection criteria included the self-reported experience of displacement, the availability of at least two members of the family group who were from different generations, and the ability to communicate with the interviewer in a common language. As determined by the participants, displacement had to be the only option available to maintain or achieve their families’ well-being.Three in-depth audio-recorded interviews, lasting between 30 minutes and 2 hours, were conducted with each family between September and December 1996. At least one interview included family members from two generations. The majority of interviews were conducted face-to-face in participants’ homes, with a few conducted at workplaces, in public areas, or over the telephone.Interviewers transcribed all of the interviews and created a summary of each family’s story. The 20 sets of summaries, field notes, interview transcripts, and essays written by each interviewer on a theme related to displacement provided a robust qualitative dataset for our analysis.This study was approved by the Harlem Hospital Institutional Review Board. All participants signed informed consent forms.

Analysis We conducted a two-stage analysis of this qualitative dataset. In the first stage, we developed an extended summary of displacement events, which supported the construction of a timeline for each family and identification of themes characterizing the displacement process. In the second phase of the analysis, we examined and coded the costs associated with displacement using the concepts of social, cultural, and economic capital.

Results

Table 1 provides a breakdown of the families by country and reasons for displacement. The 20 families represented 18 countries and six different types of displacement situations. Experiences of displacement ranged from the immigration of Italians to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century to the arrival of immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in the United States near the end of that same century. Limited economic opportunity was the most common reason for displacement. Ethnic and/or religious persecution was also a frequently reported reason for displacement, which not only forced families to leave for safety reasons (for example, Family 3), but through institutionalized discriminatory practices, i.e., severely hampered educational and economic prospects within the country of origin (Family 19).

Table 1.

Summary of families’ displacement experiences [all relations in the table are with respect to the offspring in the nuclear family]

| Family # | Country of origin | Reasons for displacement | Capital gains | Capital losses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | • Limited economic opportunities | • Career opportunities for mother | • Familiar and beloved house |

| • Reunite with elderly, dying parent | • Time spent with elderly, dying parent | • Friends and community | ||

| • Secured employment | ||||

| 2 | Iraq | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Safety | • Family’s affluence |

| • Freedom | • Time to spend with children | |||

| • Adverse effect on child’s social development | ||||

| 3 | Germany | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Safety | • Value of educational degree |

| • Freedom | • Religious faith | |||

| • Emotional trauma | ||||

| 4 | Ukraine | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Freedom | • Family possessions |

| • Improved economic status, housing and availability of food | ||||

| • Feeling equal (not inferior) | ||||

| • Support from resettlement organizations | ||||

| 5 | Latvia | • Institutional persecution | • Economic opportunities | • Social status |

| • Limited employment opportunities | • Son’s ability to pursue a sport career | • Mother’s career ended | ||

| • Father’s business | ||||

| 6 | Egypt | • Limited economic opportunities | • Integration in ethnocultural community | • Father’s loss of value of occupational skill |

| • Maintaining heritage | ||||

| 7 | Russia | • Fear of communism | • Economic opportunities | • Inconsistency in children’s education |

| Venezuela | • Uncertain future | |||

| 8 | Dominican Republic | • Limited economic opportunities | • Improvement in social status | • Difficulty with cultural identity for younger generation |

| 9 | Russia | • Ethnic/religious Persecution | • Religious freedom | • Places of significance |

| • Economic opportunities | • Family possessions | |||

| 10 | USA | • Son’s illness | • Healthy environment for son | • Weakened family relationship |

| • Mother learned a profession | • Adverse effects on child’s social development | |||

| 11 | Cuba | • Political persecution | • Safety | • Family members |

| • Some economic gain | • Disconnection from homeland | |||

| • Opportunities for children | • Sense of community | |||

| 12 | Italy | • Limited economic opportunities | • Family cohesion and closeness | • Homes and friends |

| USA | • Good jobs and homes at times | • Financial stability | ||

| • Need to rely on others | ||||

| 13 | USA | • Disclosure of sexual orientation | • Personal independence | • Strained relationship with family |

| • Improved relationship with mother and one brother | • Abusive relationships | |||

| 14 | Ecuador | • Son’s illness | • Medical care for sick child | • Economic opportunities |

| • Educational opportunity for child | • Safety (from neighborhood crimes) | |||

| 15 | Greece | • Limited economic opportunities | • Economic opportunities | • Family and friends |

| 16 | Guyana | • Ethnic/political persecution | • Opportunities for children | • Disconnection from homeland |

| • Limited economic and education opportunities | • Employment opportunities for mother | • Familiar foods and places | ||

| 17 | Russia | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Opportunities for children | • Family possessions |

| • Limited educational opportunities | ||||

| 18 | Russia | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Unclear | • Friends |

| • Uncertain future | • Family home and possessions | |||

| • Mother’s and father’s careers | ||||

| 19 | Korea | • Limited economic and educational opportunities | • Economic opportunities | • Family and friends |

| Argentina | • Valued possessions | |||

| • Careers | ||||

| • Places of emotional significance | ||||

| 20 | Iran | • Ethnic/religious persecution | • Religious freedom | • High standard of living |

| • Limited educational opportunities | • Economic and educational opportunities | • Friends | ||

| • Morals and values of homeland | ||||

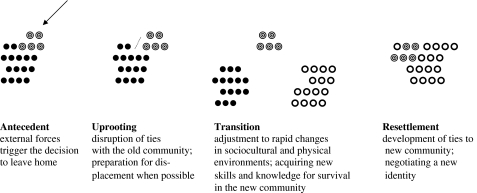

Despite many situational differences among the 20 families, a common process of displacement, consisting of four phases, was identified. In the beginning, social and economic pressures led to atomization of the family, creating a small group that was disconnected from its larger social network. This fragmented and vulnerable unit traveled to a new community and made repeated attempts to regain its lost social ties. This process of disconnection and reconnection was accompanied by massive shifts in social, cultural, and economic capital. The four phases of displacement described in the section that follows are shown schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phases of displacement.

The Phases

Antecedent

In the antecedent phase, one or more changes in social, political, or economic conditions triggered the process of displacement. In some cases, this change created an urgent, often unsafe, situation. Family 2 was compelled to leave following a series of kidnappings and other disappearances of members of their ethnic group. In other cases, the change served as the final push for the move, while still at other times, the change afforded a new opportunity to escape long-term adverse conditions. One woman’s account provides an example of the latter:

The iron curtain was lifted. Then [son and daughter-in-law], they go first, then we a little bit later, because my mother… was very sick… and I couldn’t leave her and I couldn’t take her. She died in 1989. My father died earlier. But we wanted a little bit in the elderly years, a little bit freedom, a little bit that we can be Jewish people, that we can speak Jewish, that our children will see the free world. We wanted to go to Israel, but [our family] are very happy here in America… we decided to be together with the children and we came to America (Family 5).

As the above quote illustrates, family preservation was a major factor in the decision to uproot. For instance, when one member of the family was adversely affected, the desire to maintain family solidarity forced the entire family into displacement. Family members, particularly parents, were willing to tolerate personal losses and hardship if displacement resulted in improvements in children’s opportunities for success and happiness. For instance, Family 20 endured the loss of a high standard of living, family home, and many possessions, as well as their friends and cultural values and norms, in exchange for gaining religious freedom and educational opportunities for their children. In another family, a father explained a similar reasoning for moving his family from Guyana to New York City to improve the employment opportunities for his wife and the educational opportunities for his children. These were limited by racial conflict in the country of origin (Family 16).

Although families engaged in efforts to predict possible outcomes in the face of imminent displacement, information about intended destinations and consequences of displacement was scarce. Most families could prepare very little for what lay ahead. Seeped with uncertainty about pending upheaval, the antecedent period was described as an emotionally wrenching and difficult period.

Uprooting

Uprooting, the second phase in the process of displacement, involved breaking longstanding ties with friends, family, and communities. It entailed resigning from jobs and withdrawing from schools and religious affiliations. As a result, individuals were no longer able to engage in their routine daily activities. In addition to the ensuing loss of stability and security, families in this phase were disconnected from friends at work, school, and places of worship. Some were forced to sever ties with friends and extended family members long before leaving in order to protect those who remained behind. These families were no longer able to call on others in the community for help with day-to-day activities and emotional support. A woman in our sample described her experience:

Beginning with the resignation from work, then filling out hundreds of forms and being cut out from all society, like an untouchable… everyone that knows you would be afraid to see you because the fact that you were leaving meant there was something wrong with you… [we] had to take the kids out of school so they wouldn’t be harassed (Family 17).

In many cases, governmental restrictions limited the amount of cash and valuables that the émigrés could take with them. Governments confiscated family homes that were not sold prior to leaving and took cash savings over and above the amount that was permitted to leave the country. Families were forced to sell or give away their possessions and spend their life savings in a short period of time, leaving limited cash resources for moving and resettlement costs. While some valued possessions could be saved, others were lost forever. For instance, one grandmother was able to take her wedding crystal, but a lifetime’s collection of books had to be left behind (Family 9). A young man also recalled that rather than allow the government to prosper on their behalf, his family decided to spend the money they would not be able to take on expensive activities (taking taxis) or items (cakes) (Family 17).

Transition

The transition phase was characterized by rapid changes in physical and social environments. Families in this phase were between communities, as they had severed ties with the old community, but had not yet developed connections to the new one. Families were actively engaged in adapting to their new community by confronting barriers and mourning their losses. Survival was the main goal. Families had to learn a new language, find employment, become familiar with new surroundings, and obtain basic amenities such as shelter and clothing. In some cases, not knowing the language prevented families from mastering their new environment. For example, when a family did not have a command of the language, their employment opportunities were further limited. Some families lacked resources that would have enabled them to learn the language.

One woman confessed to her frustration with the language barrier and the subsequent sense of isolation it created:

Many times I felt as if life was being choked out of me. I wanted to talk with people; I wanted to know what was happening in the world around me (Family 19).

Cultural losses were also significant during the transition phase. Familiarity with social norms and cultural rituals was replaced with the unfamiliar. The knowledge of one’s society and its norms, accumulated over many years and so valuable in the old community, were no longer applicable in the new community. Families coped by finding ethnocultural communities or surrounding themselves with the art, food, and language of their culture within their home. Adjustment required a relearning process, which involved constant negotiation between the old and new cultures and continued to be a strong theme and a significant challenge throughout the displacement process.

A critical task during the transition phase was finding employment. Families’ search for employment was guided by two conflicting needs. First, the need for survival created an urgency to find employment—any employment—as quickly as possible. Second, the need to build upon prior experience pressured individuals to seek employment within their professions. After one participant’s husband was unable to find work in his field, she tried to find employment for herself by reconciling her previous experience with her current capabilities.

…My mother-in-law’s friend helped me to get some job. She sent me to the Board of Education and I told her I used to be a teacher but I don’t speak English, so I’ll be happy to take any job, and they said, would I like to go in the lunchroom and serve lunch to the kids. I say any job… I have to make some money, and what can I do? (Family 5).

Employment had a significant impact on the availability of family members for family activities. Physical distance was created when employment forced family members to take jobs away from the family. This is best exemplified by a wife and mother (Family 18) who, although able to continue her career as an engineer, was transferred between projects by her company and had to live away from her family for four years. The lack of availability of family members manifested as emotional distance. In Family 2, the parents invested most of their time and energy into building a new business, leaving their children to be cared for by a nanny. Feelings of abandonment were expressed by the children in interviews conducted with them as adults.

Families mourned what they had lost as a result of displacement. Losses included familiar people and places, as well as material possessions. Families regretted not being able to visit special places such as family gravesites (Family 9) or being able to smell familiar scents such as coffee bean plants in the morning (Family 11). Possessions that had been lost, left behind, or given away had to be replaced:

I used to cry every day. My husband and I felt lost. We sold everything we owned in Argentina to come to America. We had to start everything again. We used to work for 18 hours [a day,] seven days a week (Family 19).

When available, families depended on the help of other family members or formal organizations. The New York Association for New Americans played a significant role in assisting families from the former Soviet Union with accessing apartments, language classes, and employment. Informal sources of support were also tapped into by families. For example, relatives provided care for children while the parents tried to establish themselves in the new community. Some received generous support from others who had resettled before them. One Holocaust survivor recalled the assistance he received.

First of all, my brother-in-law had a cousin… also a refugee, but… in the United States for… 3 or 4 years. He offered me a room in his apartment, and that was very nice. But that was no problem to find a room, you know, because many refugees that had an apartment, rented rooms to other refugees (Family 3).

Resettlement

As families proceeded to the resettlement phase, they focused their efforts on developing connections to their new communities. They achieved financial stability during this phase by obtaining employment, starting their own business, purchasing a house, or securing their children’s educational future. One man explained:

I’m satisfied in seeing my children receive a good education. I came to do better than I was doing in Guyana. The government is better and I am better off in many ways. If I was in Guyana right now, I’d be fearful of many things. My children have the opportunities to advance themselves (Family 16).

Other families entertained doubts about the irreversible losses that they had incurred. As one family member explained:

[Moving to Pennsylvania] was traumatic in trying to find our way in this community… it hurt me that no one welcomed us to the neighborhood… I cried the first six months… There was much anxiety… There was worry about living comfortably and what retirement would be like since [my husband’s] salary was now cut in half… the anxiety and guilt in moving the family to take this job wears on me (Family 1).

During this phase, families developed a new cultural identity. Families faced three options: (1) assimilation, especially for the younger generations, (2) developing an integrated cultural identity, or (3) maintaining their old cultural systems. An Iraqi family (Family 2) who immigrated to the United States more than 50 years ago strongly believed in assimilation and spoke only in English in public to show respect to the culture and people of their new homeland. Access to an ethnocultural community helped to ensure a sense of continuity and provided concrete assistance with a multitude of needs during the initial phases of upheaval. However, heavy reliance on such communities limited interaction with the larger society and culture, complicating identity reformation and in some cases leading to some degree of marginalization. One participant felt this had occurred in his community.

What Dominicans have done in Washington Heights and Inwood [neighborhoods in New York City] is that… they have taken cultural elements of the environment and cultural elements of their culture of origin and combine them together to create an identity that is different… it allows[for] the preservation of their culture. The problem is it really encapsulates them and it doesn’t allow them to grow (Family 8).

Development of an integrated identity, one that incorporated elements of the old and the new cultures, created confusion and problems with acceptance by members of both communities. A US-born woman of Dominican descent described the problems she faced in this regard:

Family and friends in [the Dominican Republic] would always introduce [her and her sister] as Americans… and I remember that as such a big thing. I had not even thought about that. I had not thought about defining myself as… American or Dominican or Dominican-American… [on another occasion, walking in New York City and speaking English], people saying: “Oh look at these people speaking English making believe they’re American and they’re Dominican,” and we were like, oh God, we didn’t do it on purpose (Family 8).

Families finally achieved a sense of resettlement when one or more family members developed significant connections to the new community. The mother in the above Dominican family explained how her children’s ties with school and community determined where she found happiness:

I prefer life here. I had my children here. I had gotten married here… when I returned to Santo Domingo again I had to leave everything… My children were in school [in the US] where everything was different… I was not very happy… all my family was here [in the US] (Family 8).

Discussion

Summary

In studying the displacement experience of families as a unit, we found a four-phase process of displacement: antecedent, uprooting, transition, and resettlement. During the process, displaced families become disconnected from their larger network of relationships, which were nestled within the physical space they previously occupied.

The costs associated with displacement took several forms and were borne by multiple generations. Breaking social ties reduced families’ access to valuable information, knowledge, and interpersonal resources. Families endure great financial loss in the form of physical materials as well as economic opportunities. “De-skilling,” a reduction or loss in value of skills and knowledge (often due to the language barrier), was a common experience. Finally, life-long linguistic and cultural knowledge lost its value.33

Losses for all families stemmed from the fact that group connections are not always transferable from one sociogeographic setting to another. Families who were able to maintain strong ties among their members drew heavily on the capital within the family. Families worked hard to establish or strengthen ties to the new sociogeographic and/or affinity communities. When preexisting associations provided access to sources of formal or informal social support, families were more successful in reaching the resettlement phase. Prior research has shown that support systems serve as an essential route for contact and for weaving new additions into a community and a community into a socially cohesive entity.34,35 In addition to its role in promoting economic and civic well-being, social cohesion has been shown to favorably affect the physical and mental health of communities and their members.18,30,36,37 Social capital also brings coping skills and opportunities to engage in fun or relaxation, which can further reduce the stress that displaced families and individuals experience.2,20,21,23

Our findings also suggest that families without these support systems experienced a more difficult transition phase and that their progress to the resettlement phase proceeded at a slower rate. Issues such as language barriers, lack of understanding of culture and customs, or experiences of traumatic conflict often prevented families from attaching themselves to the support systems that would help them overcome these barriers. These barriers also hindered families’ contributions to the social and economic capital of their new communities.

Given these findings, the receiving communities stand to benefit from the social integration of displaced individuals and groups. Communities that invest in physical and social structures such as meeting places and mechanisms for sharing of resources are more likely to possess durable networks and are therefore better equipped to promote social integration. Developing and maintaining local institutions that promote collective actions and efficacy cannot only help to address problems taxing displaced families and the communities in which they settle, but by improving community stability, such investments have the potential to prevent future population displacement.

Strengths and Limitations

By collecting extensive in-depth data from multiple members of the family, we were able to use the different perspectives of family members to develop a model of displacement process that captured the overall family displacement experience. Our study location, New York City, was uniquely suited for the current study. Many displaced individuals arrive in, and often resettle in, large urban areas. While urban environments provide many economic opportunities, they are also complex and intimidating social and physical environments, particularly for those arriving from rural or small communities.

Our qualitative study was not intended to have high generalizability and is limited by the small sample size and convenience sampling strategy. In addition, our study participants had relatively high socioeconomic standing which may have facilitated their adjustment and success in the receiving communities. Moving to the United States, a resource-rich nation, may have led to more favorable outcomes and/or faster resettlement. The majority of internationally displaced populations resettle in neighboring developing countries that are less likely to possess adequate socioeconomic and material resources to support or integrate refugees, migrants and other displaced groups.38 Internally displaced populations from low socioeconomic backgrounds may also be at a disadvantage because of the emphasis put on individual agency and policies that limit their ability to choose a receiving community that is “better off” than their community of origin. We were successful in recruiting a sample of families with heterogeneous displacement experience in order to glean a common process through diverse experiences. Nonetheless, there are many other displacement experiences that were not captured in our sample.

Despite these limitations, our study provides new information about the entire process of family displacement and about short- and long-term impact on personal and interpersonal capital. These are unique and previously unexplored research areas with high relevance to the health and well-being of the rising number of displaced individuals and communities. Our model of family management of displacement would benefit from further confirmation and refinements using other study populations and displacement situations.

Conclusion

The families interviewed for this study were widely diverse in their composition, ethnocultural background and life experiences. Yet their accounts collectively describe displacement as a process consisting of four phases, and add to our knowledge about the full course of the displacement experience. The study findings also contribute to our understanding of the process of reconnection and the importance of social connectedness. Loss is an inevitable consequence of displacement and restitution of what is lost is never guaranteed.

To a growing number of people, displacement has been or will be an inescapable and difficult experience. Attention should be paid to the intangible losses families are bringing with them and the effects on the health and well-being of these individuals and their communities. The degree to which the displacement process ends successfully, or ends at all, can be affected through efforts aimed at recreating social connections. While we emphasize the stake-holding role of the receiving communities and the role they can play in alleviating problems leading to and arising from displacement, we acknowledge that displacement has a global impact and that these ends are achieved only with the aid and commitment of the larger political systems, and should be advocated on national and international levels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Environmental Health, under the “Healthy Home Initiative,” to the Harlem Center of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. We thank the students of Qualitative Research Methods I in 1996 for their work on collecting, transcribing, and analyzing the data and the students of Qualitative Research Methods II in 2001 for their insightful comments on the analysis plan and early results. We also thank Donna Patris for her assistance in collecting articles for the literature review and confirming references.

Contribution MT Fullilove conceptualized the study, oversaw the data collection, helped with the writing of the paper, and provided valuable mentoring on all aspects of data analysis and writing. D Greene, P Tehranifar, and LJ Hernandez-Cordero participated in the analysis and contributed to the initial writing of the paper. D Greene and P Tehranifar led the writing. LJ Hernandez-Cordero and MT Fullilove offered critical insights and revisions to the final paper.

Contributor Information

Danielle Greene, Email: dgreene@health.nyc.gov.

Parisa Tehranifar, Email: pt140@columbia.edu.

Lourdes J. Hernandez-Cordero, Email: ljh19@columbia.edu

Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Email: mf29@columbia.edu.

References

- 1.Statistical yearbook 2009: trends in displacement, protection and solutions. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Garfield R, Redlener I. Prevalance and predictors of mental health distress post-Katrina: findings from the Gulf Coast Child and Family Health Study. Disast Med Pub Health Prepar. 2008;2:77–86. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318173a8e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher M. Rain adds to misery of 1.3 million left homeless after Haiti earthquake. The Times. 2010. Accessed May 18, 2011.

- 4.Tabuchi H, Pollack A. Powerful Aftershock Complicates Japan’s Nuclear Efforts. New York Times. April 7, 2011, 2011; World.

- 5.Fullilove M. Root shock: how tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America and what we can do about it. New York, NY: Vallentine Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker C, Arseneault AM, Gallant G. Resettlement without the suppport of an ethnocultural community. J Adv Nurs. 1999;20:1064–1072. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20061064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beiser M, Hou F, Hyman I, Tousignant M. Poverty, family process, and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):220–227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birman S, Beehler S, Harris E, et al. International Family, Adult, and Childen Enhancement Services (FACES): a community-based comprehensive model for refugee children in resettlement. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(1):121–132. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fullilove M. Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psycology of place. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;253:1516–1523. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauff EVP. Organized violence and the stress of exile: predictors of mental health in a community cohort of Vietnamese refugees three years after resettlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:360–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanango S. Counseling families affected by socio-politcal factors and economic hardships. Int J Adv Couns. 2004;26(4):351–361. doi: 10.1007/s10447-004-0170-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert MC, Brown V, Villagi F, Boiret I. Malnutrition in displaced persons in Zaire. Lancet. 1994;343:1296. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipson K. The health and adjustment of Iranian immigrants. West J Nurs Res. 1992;14:20–39. doi: 10.1177/019394599201400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall G, Schell T, Elliot M. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(5):571–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silove D, Sinnerbrink I, Field A, Maincavasagar V, Steel Z. Anxiety, depression, and PTSD in asylum-seekers: associations with pre-migration trauma. Br J Psyhiatr. 1997;170:351–357. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sastry N, VanLandingham M. One year later: mental illness prevalence and disparities among New Orleans residents displaced by hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(S3):S725–S731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace R. A syngergism of plauges: "planned shirnkages" contagious housing destruction and AIDS in the Bronx. Environ Res. 1988;47:1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0013-9351(88)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomas J. Social capital and health: implications for public health and epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(9):1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawachi I, Kennedy B. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:215–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putnam RD. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of the American community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2000. p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1501–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:1121–1127. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krisotakis G, Gamarnikow E. What is social capital and how does it relate to health? Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00097-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen DA, Farley T. Prescription for a healthy nation: a new approach to improving our lives by fixing our everyday world. Boston, MA: Beacon; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poortinga W. Social relations or social capital? Individual and community health effects of bonding social capital. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:255–270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpiano R. Neighborhood social capital and adult health: an empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health Place. 2007;13(3):639–655. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood L, Giles-Corti B. Is there a place for social capital in the psychology of health and place? J Environ Psychol. 2008;28:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1995;94(supplement):S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Kelly M. Twanda’s triumph: social and cultural capital in the transition to adulthood in the urban ghetto. Int J Urban Reg Res. 1994;18:89–111. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawachi I, Kennedy B. The relationship of income inequality to mortality: does the choice of indicator matter? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1121–1127. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borjas G, Bronars S. Immigration and the family. J Labor Econ. 1991;9:121–148. doi: 10.1086/298262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granovetter M. Strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol. 1973;78:1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viruell-Fuentes EA, Schulz AJ. Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2167–2175. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fullilove M. Promoting social cohesion to improve health. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1998;53(2):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walberg P, McKee M, Schkolnikov V, Chenet L, Leon D. Economic change, crime and mortality crisis in Russia: regional analysis. BMJ. 1998;317(7154):312–318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.2008 Global trends: refugees, asylum-seekers, returnees, internally displaced and stateless persons. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 2009. [Google Scholar]