Abstract

Struening et al.1 demonstrated a widening disparity of low birthweight (LOB) rates among New York City health areas from 1980–1986, clearly a dynamic process. In contrast, the New York City Department of Health reported static citywide LOB rate in 1988–2008.2 Struening et al.1 is extended here at the health district level with mapping and regression analyses. Additionally, birthweight data are reported for babies born in 1998–2001 to a group of African-American and Dominican women in Upper Manhattan. The data reported in this paper indicate that both fetal programming of the mother herself (life course model) and stress during or shortly before pregnancy may play a role in LOB. Current stress may arise from past events. Intergenerational effects, thus, could arise from stresses on the grandmother and their residual impacts on the mother as well as new stresses on the mother as an adult. The average weight of babies born to the Upper Manhattan mothers who were born in 1970–1974 was 3,466 g, with 1.6% below 2,500 g; that of babies of mothers born in 1975–1979, 3,320 g, with 6% below 2,500 g. The latter group was born during the 1975–1979 housing destruction. Intergenerational impacts of that event may be reflected in this elevated rate of LOB. Health district maps of LOB incidence ranges show improvement from 1990–2000 and then deterioration in 2005 and 2008. Bivariate regressions of socioeconomic (SE) factors and LOB incidence showed many strong associations in 1990; but by 2000, the number and strength of these associations declined. In 1990, 2000, and 2008, black segregation was the SE factor most strongly associated with LOB. Black segregation and murder rate explained about 85% of the pattern of 1990 LOB. Regressing the 1970–1980 percent population change against the SE factors showed effects even in 2000. The 1990 murder rate and 1989 percentage of public assistance explained over half the 2008 LOB incidence pattern. The housing destruction of the 1970s continued to influence LOB incidence indirectly in 2008. The ability of community and individual to cope with current stressors may hinge on resilience status, which is shaped by past events and circumstances. The present interacts with the past in many ways. Serial displacement exemplifies this interaction of immense importance to public health.

Keywords: Serial displacement, Intergenerational effects, Geography of low-weight births, Influences on low-weight birth patterns

Introduction

Low-weight births have long occupied the American health disparities research agenda because African-American mothers have a much higher risk of a low-weight baby than do white mothers. Struening et al.1 examined the effect of the 1970–1980 change in number of housing units on frequency distribution of low-weight births in the 380 health areas of New York City. Although the average and median proportion of live singleton babies weighing less than 2,500 g declined between 1970 and 1980 and between 1980 and 1986, variance and range increased greatly, as did the maximum. Well over half of the variability in proportion of births below 2,500 g in the health areas with over 90% of the population African American and with increases in low birth weight (LOB) over 1% between 1970 and 1980 was explained by the decrease in number of housing units between 1970 and 1980. Struening et al. reviewed the literature on factors fostering high proportions of LOB: housing overcrowding, family instability, family income, and neighborhood socioeconomic status. They concluded that the housing destruction of the 1970s led to a polarization in the quality of births between the poor communities of color and the rest of New York City: “The range of minimum and maximum values, which increased from 0.144 to 0.190 to 0.226 for 1970, 1980, and 1986, respectively, document the change in degree of polarization. Health areas in the high low birth weight tail experienced the greatest amount of housing destruction and community devastation between 1970 and 1980.”

The New York City Department of Health’s 2008 Summary of Vital Statistics2 presented a graph showing proportion of live births of less than 2,500 g by year from 1988–2008. The caption includes the sentence, “The percent of low birthweight babies has remained stable for the past 20 years.” This situation contrasts with the decline documented by Struening et al.1 in percents of LOB between 1970 and 1986: 8.9% (1970), 8.2% (1980), and 8.0% (1986) despite the increase in LOB in communities of high housing destruction. Indeed, for some years during 1988–2008, the citywide percent of LOB greatly exceeded that of 1970 (figure 24).

The literature on LOB and psychosocial and socioeconomic (SE) factors is rich and of long standing. David et al.3 showed that African American mothers had low-weight babies at a much higher incidence than African mothers, implying that US SE factors distressed African American mothers. Roberts4 showed that neighborhood and neighborhood characteristics influenced patterns of low-weight births in Chicago. Texeira et al.5 found that pregnant women troubled by anxiety had a higher uterine artery resistance than those without anxiety. State and trait anxiety both were effective. They concluded that this physiological impairment from anxiety might explain at least part of the consistent relationship between maternal anxiety and low-weight births.

Barker et al. examined life courses and long-term health of Finns in the Finnish registry. Birth weight and early childhood growth determined many adult health patterns such as risk of coronary heart disease.6 People in the registry who were low-weight neonates exhibited much higher prevalence of anxiety in their senior years.7 This cohort showed hypersensitivity to stress of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis. This anxiety probably arose well before age 60. Between the finding of Texeira et al. that anxious pregnant women have a physiological impairment which may lead to low-weight births and the finding of the team studying the Finnish registry that low-weight babies ended up as anxious adults, a potential vicious circle arises which implies intergenerational effects of anxiety and stress.

Although multigenerational studies on birth quality and its determinants are scarce for humans, animal models are numerous. One of the most recent reports concerns the famous cycling of the snowshoe hare population.8 The peak-to-peak period of the cycle is about 10 years; that of the major predator (Canadian lynx) is also 10 years but lagged behind that of the hare. Predation is the major determinant of the hare’s cycle. At the peak of the lynx cycle, predation pressure on the hare is intense (percentage of chance of being eaten).

Sheriff et al.8 noticed that when predation pressure crashed, the increase in hare population was delayed for no obvious reason. Food was abundant; predators were at low population levels. Sheriff et al. found that the females of the intensely preyed-upon generation had high levels of hare stress hormone in their urine and gave birth to fewer and smaller offspring. The second generation (the fewer and smaller offspring) also had high levels of stress hormone in their urine and also gave birth to fewer and smaller offspring than the generations of the upswing and peak of the hare population cycle. Thus, the stress of intense predation lingered to the F3 generation although the only generation to have experienced it was the F1.

In this paper, I shall discuss the possible factors behind the stubborn health problem noted by the New York Department of Health in the context of Struening et al.1 I shall examine (1) population level geographic patterns of low-weight birth incidence across the 30 health districts of New York City over time and (2) birth weights of babies born to women living in Upper Manhattan who themselves were born during different stages of the housing destruction described by Struening et al. Both intergenerational influences and conditions prevalent around the time of the birth will be examined as potential contributions to incidence of low-weight births.

Methods

The two sets of data and analyses here consist of birth records of a cohort born in 1998–2001 to mothers recruited by the Center for Children’s Environmental Health at the Joseph Mailman School of Public Health (Columbia University) and health district data (both birth weights of live births for 1989–2008 from the Annual Summary of Vital Statistics published by the New York City Department of Health and SE census data posted on InfoShare). New York City designated 30 health districts in the late 1960s, each with roughly 100,000–300,000 people.

Statgraphics 5 Plus for Windows was used for the statistical analyses of these two data sets.

The recruitment of the expectant mothers of the birth cohort is described in Wallace et al.9 The babies’ weights were grouped according to the year of the mother’s birth: before 1965, 1965–1969, 1970–1974, 1975–1979, and 1980 and later. The descriptive statistics of these grouped birth weights were generated (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum). T test and Mann–Whitney non-parametric test were applied to compare the means of the grouped weights. The percent of low-weight newborns in each group was also calculated.

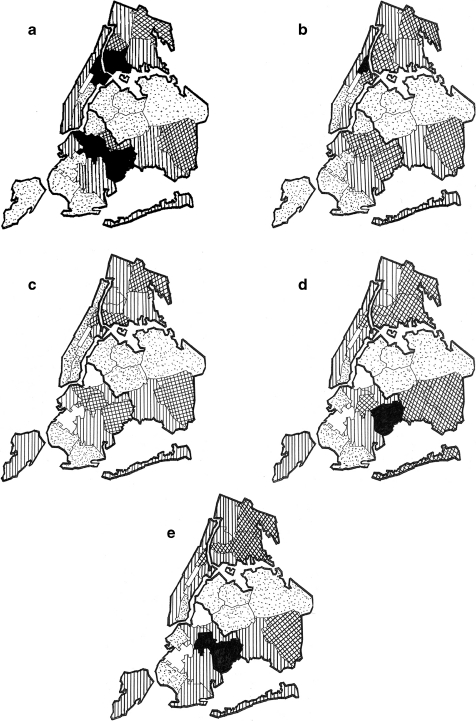

The mean annual incidences of low-weight births of the health districts were mapped for 1989–1991, 1994–1996, 1999–2001, 2004–2006, and the sole year of 2008. The maps displayed Health Districts with the following ranges of incidence: 12% or above, 10–11.9%, 8–9.9%, 6–7.9%, and below 6%.

Bivariate and stepwise backwards multivariate regressions were performed with the percent of low-weight births of the Health Districts as the dependent variable and the SE variables as the independent variables to explore associations between incidence of low-weight births and SE factors. The SE factors included population change between decadal censuses (1970–1980, 1970–1990), median income, percent in poverty, percent with public assistance, percent unemployed, percent adults without a high school diploma, the racial/ethnic composition of the health district, and incidence of homicides per 100,000 persons. Except for the population data which included 1970 census data, the SE variables were drawn from 1980, 1990, and 2000. The regressions explored associations of the mean low-weight birth incidence of 1989–1991 with the SE variables of 1990, with the exception of the 1970–1980 and 1970–1990 percent changes in population. The same regressions were conducted for the mean low-weight birth incidences of 1999–2001, with the appropriate SE variables from the 2000 Census. The percent of live births with weights under 2,500 g in 2008 was the dependent variable for the last set of regressions and the SE variables were necessarily from the 2000 census because the data were not yet available from the 2010 Census at the Health District level.

Additionally, the SE variables of the 1990 and 2000 censuses were regressed against the population changes of 1970–1980 and 1970–1990 to explore whether population instability was associated with such factors as homicide incidence, unemployment, segregation, and other variables that were associated with patterns of incidence of low-weight births.

An index of segregation was calculated as follows: the percent African-American of the health district was divided by the percent African-American of the entire city. A similar index of segregation was calculated for the “Hispanic” population. These indices were independent variables in the bivariate regressions also.

Results

Upper Manhattan Birth Cohort

The birth weights of the babies born to the mothers studied in Wallace et al.9 are summarized in the text table below. These mothers lived in areas affected by the 1970s mass housing loss. Contrary to the weathering explanation by Geronimus10 and contrary to the cross-sectional finding by Rauh et al.11 that the older the African-American mother, the lower the baby’s birth weight, mothers born 1975–1979 had markedly smaller babies than mothers born in 1970–1974. Indeed, 6% of the babies born to the mothers of the 1975–1979 cohort had weights less than 2,500 g, whereas only 1.6% of those born to the 1970–1974 cohort had such low weights. However, all the maternal age classes had much lower incidence of low-weight births than did the home neighborhoods and than did the entire city.

| Mother’s birth year | before 1965 | ’65-‘69 | ’70-’74 | ’75-’79 | ’80 and later |

| Number | 15 | 38 | 63 | 116 | 61 |

| Babies’ mean birth weight (g) | 3375 | 3405 | 3466 | 3320 | 3391 |

| SD | 503 | 470 | 535 | 504 | 448 |

| %below 2500g | 6.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 6 | 3.3 |

Thus, the babies born to mothers born during the 1970s destruction of housing had a much higher probability of LOB than those born to mothers born immediately before that event.

The Changing Geography of Low Birthweight Incidence 1990–2008

Maps

The target for LOB incidence set in Healthy People 201012 is 5%. No health district reached that level during the 1989–2008 period although two eventually came close.

For 1989–1991 (Figure 1a), the average for Central Harlem was 18.4%; for Morrisania and Mott Haven (Bronx) about 13.5%; and for Bedford (Brooklyn), 13.2%. The other health districts in the worst category had incidences close to 12%.

FIGURE 1.

Maps of incidences of low-weight births by health district. Black incidence of 12% or above, cross-hatching incidence 10–11.9%, stripes incidence of 8–9.9%, stipple incidence of 6–7.9%, white incidence below 6%. a Annual average incidence 1989–1991, b annual average incidence 1994–1996, c. annual average incidence 1999–2001, d annual average incidence 2004–2006, e annual incidence 2008.

By 1994–1996 (Figure 1b), only Central Harlem had an annual average LOB incidence above 12%: 14.8%. Additionally, the Lower West Side of Manhattan entered the 6–7.9% category, dropping from 8.2% to 7.1%.

By 1999–2001 (Figure 1c), many districts had further improved. None had incidence of 12% or more. All but two districts of Manhattan dropped into the 6–7.9% category. Of the two Manhattan districts not in the 6–7.9% category, East Harlem improved from the 10–11.9% to the 8–9.9% category. Two Brooklyn districts (Sunset Park and Williamsburgh–Greenpoint) entered the best category (<6%). All but two districts of the Bronx had improved into the middle category of 8–9.9%. However, Richmond (Staten Island) worsened into that middle category.

Figure 1d (2004–2006) shows deterioration from the improvements of 1999–2001. Of the Manhattan districts, only the Lower East Side remained in the 6–7.9% category. In the Bronx, only two districts remained in the 8–9.9% category. Brownsville’s incidence exceeded 12%; and Jamaica West in Queens, 10%.

In 2008 (Figure 1e), Brownsville was joined by Bedford in the worst category (over 12%). However, Mott Haven in the Bronx and Jamaica West in Queens improved into the 8–9.9% category. Sunset Park’s LOB incidence approached the national target (5.3%).

Regressions

In simple regressions, the 1989–1991 average LOB incidences were associated significantly with most of the selected measures (Table 1). The two measures with highest R2 were black segregation and murders per 100,000. Unemployment rate also shows a high R2. When we look at the regressions of these socioeconomic measures as dependent variables with the percent change in population between 1970 and 1980 as the independent, we see that many are strongly associated with that extraordinary change in population: percent in poverty, percent with public assistance, and murders/100,000 especially.

Table 1.

Average low-weight birth incidence, 1989–1991

| R2 (adjusted) | P | F ratio | Pos/Neg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple regressions: low-weight birth incidence average 1989–1991 = dependent variable | ||||

| Independent variable | ||||

| Percent difference population 1970–1980 | 0.4175 | 0.0001 | 21.79 | Neg |

| 1989 median income | 0.355 | 0.0003 | 19.96 | Neg |

| 1989% on public assistance | 0.5844 | <0.0001 | 41.78 | Pos |

| Percentage in poverty (1989) | 0.4204 | 0.0001 | 22.83 | Pos |

| Adults with no high school diploma | 0.2366 | 0.0038 | 9.99 | Pos |

| Black segregation | 0.7737 | <0.0001 | 100.16 | Pos |

| Murders per 100,000 (1990) | 0.7082 | <0.0001 | 71.39 | Pos |

| Unemployed persons/pop 16–64 years | 0.6656 | <0.0001 | 58.73 | Pos |

| Independent variable = percent population difference 1970–1980 | ||||

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Murders/100,000 (1990) | 0.6456 | <0.0001 | 53.84 | Neg |

| Black segregation | 0.1952 | 0.0084 | 8.03 | Neg |

| Percentage in poverty 1989 | 0.7383 | <0.0001 | 82.81 | Neg |

| Percentage on public assistance 1989 | 0.7392 | <0.0001 | 83.21 | Neg |

| Adults with no high school diploma | 0.5031 | <0.0001 | 30.36 | Neg |

| Unemployed persons/pop 16–64 years | 0.3724 | 0.0002 | 18.21 | Neg |

| Multivariate stepwise backward regressions: dependent variable = low-weight birth incidence average 1989–1991 | ||||

| Black segregation, murder/100000 | 0.8542 | <0.0001 | 85.94 | |

| LOB = 6.055 + 1.829 (black segregation) + 0.052(murders/100,000) | ||||

| Percent public assistance, percent poverty, unemployed | 0.7542 | <0.0001 | 30.66 | |

| LOB = 3.678 + 0.423(percent public assistance) − 0.256 (percent poverty) + 0.837(unemployed) | ||||

| Percent public assistance, adults with no diploma | 0.6645 | <0.0001 | 29.72 | |

| LOB = 9.08 + 0.409(%pub assist) − 0.138(adults with no diploma) | ||||

The stepwise regressions on Table 1 show that black segregation and murders/10,000 explained about 85% of the 1989–1991 pattern of annual average LOB incidence. Other combinations of socioeconomic measures also explained high proportions of the pattern: percent public assistance, percent poverty, and unemployment rate; and percent public assistance and adults without high school diplomas. However, the primary combination of these factors was black segregation and murders/100,000.

By year 2000, the number of SE factors that yield an R2 over 0.1 was reduced (Table 2) compared with 10 years previous. Black segregation was the sole factor with R2 above 0.6. The number of SE factors significantly associated with the percentage of the 1970–1980 population changed and their strength of association also declined. In stepwise regression, black segregation swamped all other factors associated with LOB incidence. With black segregation removed from the stepwise regression, murder rate and percent public assistance yielded an R2 of 0.57, with percent public assistance negatively associated in the model.

Table 2.

Average low-weight birth incidence, 1999–2001

| Simple regressions: low-weight birth incidence average 1999–2001 = dependent variable | ||||

| Independent variable | R2 (adjusted) | P | F ratio | Pos/Neg |

| Percent population 1970–1980 | 0.1307 | 0.0282 | 5.36 | Neg |

| Percent difference population 1970–1990 | 0.1549 | 0.018 | 6.31 | Neg |

| 1999% on public assistance | 0.3422 | 0.0004 | 16.09 | Pos |

| black segregation | 0.8027 | <0.0001 | 118.99 | Pos |

| murders per 100,000 (2000) | 0.5822 | <0.0001 | 41.41 | Pos |

| unemployed persons/pop 16–64 years | 0.4523 | <0.0001 | 24.95 | Pos |

| Independent variable = percent population difference 1970–1980 | ||||

| Dependent variable | ||||

| murders/100,000 (2000) | 0.3081 | 0.0009 | 13.91 | neg |

| black segregation | 0.11 | 0.0411 | 4.58 | neg |

| unemployed persons/pop 16–64 years | 0.4275 | 0.0001 | 22.66 | neg |

| In multivariate stepwise regression with LOB average 1999–2001 as dependent variable, Black segregation was the sole independent variable. | ||||

| Backwards stepwise regression with black segregation removed and LOB as dependent variable: | ||||

| R2 (adjusted) | P | F ratio | ||

| Murder rate2000 and% with public assist1999 | 0.5679 | <0.0001 | 25.2 | |

| LOB1999–2001 = 6.413 + 0.055(murderrate2000)-0.0147(%publicassist1999) | ||||

| Murder rate1990 and percent with public assistance 1989: | 0.5231 | <0.0001 | 16.96 | |

| LOB 1999–2001 = 7.19 + 0.109(murder rate1990) − 0.167 (percent public assistance 1989) | ||||

In 2008 (Table 3), black segregation was associated with LOB incidence with an R2 over 0.7. The 2007 Summary of Vital Statistics included health district murder rates. These murder rates were associated with the 2008 LOB incidences with an R2 of almost 0.6. Black segregation, of course, swamped all other factors in stepwise regression. With black segregation removed from the stepwise regression, murder rate of 2007 swamped all other factors. Murder rate of 2000 and unemployment of 2000 yielded an R2 of slightly over half. However, the murder rate of 1990 and the 1989 percentage of public assistance as independent variables in stepwise regression yielded an R2 somewhat greater than that of the 2000 murder and unemployment rates.

Table 3.

Low-weight birth incidence, 2008

| Simple regressions: low-weight birth incidence 2008 = dependent variable | ||||

| Independent variable | R2 (adjusted) | P | F ratio | Pos/Neg |

| Black segregation 2000 | 0.727 | <0.0001 | 78.23 | Pos |

| Murders per 100,000 (2007) | 0.5972 | <0.0001 | 43.99 | Pos |

| Murders per 100,000 (2000) | 0.5156 | <0.0001 | 31.87 | Pos |

| Unemployed persons/pop 16–64 years (2000) | 0.3959 | 0.0001 | 20 | Pos |

| Murder rate 1990 | 0.3588 | 0.0003 | 17.23 | Pos |

| Unemployed 1990 | 0.3599 | 0.0001 | 19.53 | Pos |

| Percent public assistance 1990 | 0.1648 | 0.015 | 6.72 | Pos |

| In multivariate stepwise regression with LOB 2008 as dependent variable, black segregation was the sole independent variable | ||||

| Backwards stepwise regression with black segregation removed and LOB as dependent variable: | ||||

| Murder rate 2007 and unemployed 2000: only murder rate 2007 remained as independent variable. | ||||

| Murder rate 2000 and unemployed 2000 | 0.5069 | <0.0001 | 15.91 | |

| LOB 2008 = 7.5 + 0.305 (murder rate 2000) − 0.206 (unemployed 2000) | ||||

| Murder rate 1990 and percent with public assistance 1989: | 0.5438 | <0.0001 | 18.29 | |

| LOB 2008 = 7.82 + 0.1459 (murder rate 1990) − 0.2737 (percent public assistance 1989) | ||||

Table 4 summarizes the results of the bivariate regressions and the mapping. In particular, the changes in number of health districts with LOB incidence above 12% and above 8% over time tracks the improvement and subsequent deterioration in LOB incidence across the city. In 2008, more health districts had an incidence above 8% than in the 1989–1991 average. In 2000, the above 12% category was empty; in 2008, it contained two health districts.

Table 4.

Timeline summary of health district results

| Year | Factors associated with LOB incidence in order of R2 | Factors associated with 1970–1980 population change in order of R2 | Health districts with LOB above 12% | Health districts with LOB above 8% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 20 | |||

| 1990 | Black segregation (1990) | Percent with public assistance | ||

| Murders/100,000 (1990) | Percent in poverty | |||

| Unemployment (1989) | Murders/100,000 | |||

| Percent with public assistance (1989) | Adults without high school diploma | |||

| Percent in poverty (1989) | Unemployment | |||

| Percent 1970–1980 population change | Black segregation | |||

| Median income (1989) | ||||

| Adults without high school diploma | ||||

| 1995 | na | na | 1 | 20 |

| 2000 | Black segregation (2000) | Unemployment (1999) | 0 | 18 |

| Murders/100,000 (2000) | Murders/100,000 (2000) | |||

| Unemployment (1999) | Black segregation (2000) | |||

| Percent with public assistance (1999) | ||||

| Percent 1970–1990 population change | ||||

| Percent 1970–1980 population change | ||||

| 2005 | na | na | 1 | 20 |

| 2008 | Black segregation (2000) | na: no health district data from 2010 Census yet | 2 | 22 |

| Murders/100,000 (2007) | ||||

| Murders/100,000 (2000) | ||||

| Unemployment (1999) | ||||

| Murders/100,000 (1990) | ||||

| Unemployment (1989) | ||||

| Percent with public assistance (1989) |

The listed factors had R2 above 0.1

Discussion

Four recent publications explored the geography and SE variability of LOB, especially the contrast between African-American and white births. Love et al. 13 examined Geronimus’s “weathering” hypothesis by acquiring birth certificate data of the mothers who gave birth in 1989–1991 in Cook County, IL, United States. Four groups were created: upper–upper, upper–lower, lower–upper, and lower–lower. The first designation of each group is the economic class of the mother’s neighborhood of birth, the second that of the neighborhood in which she lived when she gave birth. The rates of LOB, small for gestational age, and pre-term birth were calculated by maternal characteristics, including age, and stratified by neighborhood median income classification. In the simple comparison between African-American and white mothers, Geronimus’ “weathering” can be easily seen: the higher the age range of the African-American mothers, the higher the incidence of LOB. However, when babies of the African-American mothers classed in the upper–upper group were compared with those born of lower–lower group, only the latter showed “weathering.” Because “weathering” was not seen in the lower–upper classification, the authors concluded that LOB and small-for-gestational age incidences depended heavily on maternal economic stresses in adult life, rather than fetal programming of the mothers. However, the authors did not use an important piece of data on the mothers’ birth certificates: the mother’s own birth weight. LOB is linked to many poor outcomes which could hamper both upward economic mobility and retention of higher economic status. Thus, the data used by the authors cannot really prove that the only factor in the “weathering” phenomenon is adult economic circumstance and cannot rule out intergenerational effects.

Two papers examined neighborhood stressor effects on birth weight. Schempf et al.14 looked at births in Baltimore in 1995–1996 and used such neighborhood level characteristics as racial and economic stratification, violent crime rate (as a measure of social disorganization), and physical deterioration. Individual-level data were collected postpartum and included sociodemographic, psychosocial, and risk behavior factors. Although stress, perceived locus-of-control, and social support explained a small part of the difference in incidence of LOB between the best and worst neighborhoods, controlling, in addition, for such risk behaviors as smoking, drug use, and delayed prenatal care rendered the difference non-significant. The authors concluded that neighborhood conditions operate through the mediating factor of coping risk behaviors. Nkansah-Amankra et al.15 acquired data on 8,064 South Carolina women, their neonates, and their neighborhoods. Individual-level stress was measured and neighborhood disadvantage was classified. The results of modeling showed that stress greatly raised the risk of both LOB and preterm birth only for women living in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

In the fourth paper, Grady16 analyzed racial disparities in LOB across the census tracts of New York City in 2000. Similar results to this paper are reported in Grady: black segregation in 2000 was a major independent influence of pattern of LOB incidence. Additionally, census tract poverty rate was the major independent influence on incidence of LOB at the individual level. Thus, the two factors operated at different scales but both were important determinants of patterns of LOB.

Center Data

The birth weight data from the Children’s Center for Environmental Health at the Mailman School of Public Health (Columbia University) included over 200 babies born to women residing in Upper Manhattan (above 110 St. and west of Fifth Ave.). In the two groups of particular interest, 63 babies were born to women born before the upheaval of 1975–1979 and 116 to those born during the upheaval period. These groups are large enough to generate sound statistics. Average birth weight of neonates born to women who were themselves born during the upheaval was much lower than that of neonates born to women born before the upheaval. The percent of babies in the low-weight category born to mothers who were born during the upheaval was about four times that of the babies of mothers who were born before the upheaval, a hint that pregnancy during the upheaval was stressful to women in the affected areas and that these effects carried over into the F3 generation, just like the snowshoe hares.

This pattern of lower birth weights of babies born to younger women contradicts the findings of both Geronimus10 and Rauh et al.11 The Center neonates were born to women who did not smoke at all, take drugs at all, or drink on a regular basis. They participated in prenatal care and took advantage of all the perks that the Center offered, such as non-pesticidal pest control and apartment cleaning and repair, dietary supplements, and detailed advice on healthy living. Yet, somehow the women born during the upheaval had smaller babies on average and a much higher percent of low-weight babies than the older women born before the upheaval. This result is so startling that it merits a much larger study, perhaps with a large number of sets of birth certificates linked between mother and baby.

The women recruited by the Center were so healthy and health-minded that the rates of LOB even for those born during the 1975–1979 upheaval were much lower than the citywide rate. This is important because it also shows that the risk behaviors noted by Schempf et al.14 are also important in LOB production.

However, the data on the Center neonates somewhat contradicts the results of Schempf et al.14 that neighborhood disorganization operated through the medium of maternal coping risk behavior, such as smoking, toward the low-birth weight outcome. The Center mothers did not indulge in such risk behaviors. It appears that being born during a particular time of targeted de-housing and resulting social disorganization had direct effect on the babies and eventually on their own babies. Although low birth weight may be strongly associated with coping risk behaviors in the context of high levels of social disorganization and resulting street violence, stressors may also impact directly. The Center data are also somewhat at odds with the findings of Love et al.13 because an effect of fetal environment appears in these data.

What the Health District Maps Show

The maps of low birth weight incidences by health district show great improvement from around 1990 to around 2000, with the exception of Richmond (Staten Island). The number of health districts with less than 8% of live births below 2,500 g increased from 10 in 1989–1991 to 13 in 1999–2001. In 1989–1991, 10 health districts had incidences exceeding 10%; in 1999–2001, only seven. By 2004–2006, the tide changed. By 2008, two health districts had incidences exceeding 12%; only nine had incidences under 8%.

As the outfalls of the 1970–1980 housing destruction (high rates of murder and other violence; of illegal drug sales and substance abuse; of multipartner sexual activity; of precarious housing) began to recede in the 1990s, their impacts on LOB incidence also began to recede. Studies in New York and Baltimore had linked rates of low-weight birth with these outfalls, especially violence.14,17,18 The factors behind the deterioration from the low incidences of 1999–2001 require exploration beyond merely mapping, but we can speculate that the downturn in the economy in the early 2000s and the slide into serious economic recession after 2007 played an important role in combination with the foreclosure and housing crisis of the late 2000s.

What the Regressions Show

Ecosystem resilience theory can help interpret the results of the regressions. Holling19 articulated this theory in 1973 to explain how ecosystems deal with impacts and why they suddenly without warning may shift into an entirely different structure and function. For example: a lake may become eutrophic in a very short time. The relationships between species in an ecosystem may be either loose or tight. Ecosystems with many loose connections are resilient: they can absorb an impact with little or no visible sign. However, the impact will sever some loose connections and cause the others to become tighter. As time goes on and the ecosystem absorbs more impacts, it shifts to a tightly connected brittle network. Finally, impacts become amplified through the tight connections and eventually cause a “domain shift” (Holling’s term). Coincidentally, Granovetter20 articulated his theory of loose and tight social ties in 1973. Resilient human communities are composed of dense layers of social networks connected by many loose ties and do not collapse when impacted by the usual urban problems, but confront them and minimize them. At about the same time, theories of developmental resilience appeared in the psychology literature, as reviewed and further developed by Masten.21 Children who experienced trauma had a number of possible developmental trajectories; those with diverse family and community resources tended to develop normally. Those with narrow family and community resources retained their psychological wounds and had poor trajectories of development.

In the context of black segregation, the housing destruction of 1974–1978 led to severe domain shift as has been described in papers such as those published in the NYAM Bulletin (vol 66, #5). Massey and Denton22 describe the mechanisms of establishing and maintaining Black segregation. Certainly, the previous waves of forced displacement such as urban renewal played a role in the distribution of African-Americans in New York City in the late 1960s–early 1970s.23 The disaster of 1974–1978 shattered brittle communities and led to the epidemics of violence, drug trade, substance abuse, and other risk behaviors. The relationship between the upheaval and these outcomes has been described in many publications.24–26 Social controls in these shattered communities could not reach efficacy in the sense of Sampson et al.27 Indeed, Sampson et al. showed that residential stability is an important factor in efficacious community control.

The outfalls of the 1974–1978 upheaval peaked around 1993 and then receded rapidly (see the Summary of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health (NYC DoH) for 1993–2000 for such measures as homicide, drug deaths, and tuberculosis incidences). One may speculate that 15 years of relative residential stability led to reassertion of social control and regeneration of social support. However, the regressions show a long-lasting influence of the population upheaval of 1970–1980, both directly and indirectly. In 1990, many SES factors still showed high levels of association with the 1970–1980 population change, especially the 1990 murder rate, percent in poverty, and percent on public assistance. By 2008, the effects of the 1970–1980 population change were indirect and operated through such outfalls as the 1990 murder rate and 1989 percentage on public assistance. Indeed, the 1990 murder rate and percent on public assistance yielded a slightly higher R2 in stepwise regression with 2008 LOB as the dependent variable than did the 2000 murder rate and 2000 unemployment rate. This contrasts with the situation in 2000 when the 2000 murder rate and 2000 percentage with public assistance yielded a slightly larger R2 in the stepwise regression than did the identical 1990 factors.

By 2005, the improvements in LOB incidence seen since 1990 had begun to unravel. By 2008, deterioration was highly evident. It appears that the individual women and the entire communities that experienced the 1974–1978 upheaval and the outfalls of that upheaval through the early 1990s were vulnerable in the long-term to such events as the economic downturn of the late 2000s and the housing/foreclosure crisis. This vulnerability signals lack of resilience and fragility. Thus, past and present events interact in this deterioration in LOB incidence patterns.

The four recently published papers13–16 all examined cross-sectional data for a single year or a few years. Here, I have looked at patterns at several points in time and seen differences in both the geography of low-weight birth incidence and in the independent variables of significant influence. The particular pattern of deterioration in 2005 and 2008 hints at a deep and long-term effect of delayed outfalls of the 1974–1978 mass housing destruction, namely heightened vulnerability through decreased resilience. Historic trajectory must be part of research on low-birthweight disparities. The pattern of deterioration is also consonant with the kind of intergenerational effects seen in the Upper Manhattan birth cohort. Babies born to women who were born during a disaster or were small children during a disaster may reflect the greater vulnerability and lack of resilience of their mothers, compared with babies born to women who were born or grew up in secure, stable communities.

Conclusion

Compared with the declines in rates of LOB 1970–1986, the 1988–2008 failure to improve casts a long shadow over NYC public health. The NYC DoH statement about citywide stasis oversimplifies reality as the maps and regressions in this paper show. Because of the fragility of the people and communities affected by both the 1974–1978 upheaval and its delayed outfalls 1980s–early 1990s, the geography of LOB incidence shows active dynamics, not stasis.

African-American communities seem more vulnerable to effects of the 1974–1978 upheaval and its outfalls because previous upheavals of urban renewal, redlining, and block busting generated a stunning lack of diversity (dearth of “weak ties” à la Granovetter). The upheaval of the 1970s itself had multigenerational impacts. Serial mass displacements act like serial ecological impacts on natural biological communities: they erode resilience and lead to domain shifts à la Holling. Even if individuals move from the impacted communities, the resilience of the individual migrants has been eroded à la Masten. That migration leads to a rise in LOB incidence in the receiving communities such as Richmond and Westchester.

Besides the not strictly genetic physiological mechanisms of inheritance such as epigenetics and placental programming, we have to consider cultural transmission. Repeated attacks on African-American communities may possibly have generated a culture of anxiety and hyper-vigilance, contributing to trait anxiety, among other outcomes. Yet, very little research on the public health outfalls of culturally transmitted, event-reinforced anxiety has appeared in the literature. Segregation results in communities that share and transmit this culture. Is this dynamic part of the reason that segregation is a major determinant of health district incidence of LOB?

Much further research is needed to answer questions about the interaction between historic and present stressors in determining patterns of low birth weight incidence at a variety of scales from the individual to the community to the municipality and metropolitan region. Much more exploration of intergenerational links is clearly needed to understand these interactions. A database such as that used in Love et al.13 would be a treasure for the needed analyses, if all the available data were used that could address the question.

Clearly, there are vast areas of research yet to be explored on the question of disparities in incidence of low weight births. However, even now, we know enough to develop the public health policy of reducing the anxiety of pregnant women that stems from the threat and uncertainty of precarious housing and of communities being repeatedly destroyed by mass de-housing.

Acknowledgment

The data from the Center for Children’s Environmental Health at the Joseph Mailman School of Public Health (Columbia University) were acquired under the supervision of Robin Wyatt and Virginia Rauh and supported by the following grants: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants #P50 ES09600 and 5 RO1 ES08977-02 and US Environmental Protection Agency grant #R 827027-02.

Rodrick Wallace helped draft Fig. 1a–e.

References

- 1.Struening E, Wallace R, Moore R. Housing conditions and the quality of children at birth. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1990;66(5):463–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistical Analysis and Reporting Unit. Summary of Vital Statistics 2008. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of Vital Statistics; 2010: 53.

- 3.David R, Collins J. Differing birthweight among infants of US-born blacks, African-born blacks, and US-born whites. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1209–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts E. Neighborhood social environments and the distribution of low birthweight in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:597–603. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Texiera J, Fisk N, Glover V. Association between maternal anxiety in pregnancy and increased uterine artery resistance index: cohort based study. Br Med J. 1999;318:153–157. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker D, Osmond C, Kajantie E, Eriksson J. Growth and chronic disease: findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:445–458. doi: 10.1080/03014460902980295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raikkonen L, Pesonen A, Heinonen K. Prenatal growth, postnatal growth, and trait anxiety in late adulthood—the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheriff M, Krebs C, Boonstra R. The ghosts of predators past: population cycles and the role of maternal programming under fluctuating predation risk. Ecology. 2010 doi: 10.1890/09-1108.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace D, Wallace R, Rauh V. Community stress, demoralization, and body mass index: evidence for social signal transduction. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:2467–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geronimus A. Black/White differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:589–597. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauh V, Andrews H, Garfinkel R. The contribution of maternal age to racial disparities in birthweight: a multilevel perspective. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1815–1824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthy People 2010 objective for low-weight birth incidence: http://www.healthypeople/2010/document/html/objectives/16-10.htm

- 13.Love C, David R, Rankin K, Collins J. Exploring weathering: effects of lifelong economic environment and maternal age on low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth in African-American and white women. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(2):127–34. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schempf A, Stobino D, O’Campo P. Neighborhood effects on birthweight: an exploration of psychosocial and behavioral pathways in Baltimore, 1995–1996. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok K, Hussey J, Watkins K, Xiaofeng L. Effects of maternal stress of low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:215–226. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady S. Racial disparities in low birthweight and the contribution of residential segregation: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3013–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Campo P, Xue X, Wang M, Caughy M. Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1113–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.7.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace D, Wallace R. Scales of geography, time, and population: the study of violence as a public health problem. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1853–1858. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.12.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holling C. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Ann Rev Ecol Syst. 1973;4:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granovetter M. The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol. 1973;78:1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masten A, Obradovic J. Disaster preparation and recovery: lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecology and Society. 2008; 13: article 9. http//www.Ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss1/art9.

- 22.Massey D, Denton N. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz J. The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and Redevelopment of the Inner City. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace R. Urban desertification, public health and public order: planned shrinkage, violent death, substance abuse, and AIDS in the Bronx. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:801–836. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90175-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace R, Wallace D. Origins of public health collapse in New York City: the dynamics of planned shrinkage, contagious urban decay, and social disintegration. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1990;66(5):391–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace D, Wallace R. A Plague on Your Houses: How New York City Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled. London, England:: Verso Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson R, Raudenbush S, Earls F. Neighborhood and violent crime a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]