Abstract

HIV/AIDS stigma is a common thread in the narratives of pregnant women affected by HIV/AIDS globally and may be associated with refusal of HIV testing. We conducted a cross-sectional study of women attending antenatal clinics in Kenya (N = 1525). Women completed an interview with measures of HIV/AIDS stigma and subsequently information on their acceptance of HIV testing was obtained from medical records. Associations of stigma measures with HIV testing refusal were examined using multivariate logistic regression. Rates of anticipated HIV/AIDS stigma were high—32% anticipated break-up of their relationship, and 45% anticipated losing their friends. Women who anticipated male partner stigma were more than twice as likely to refuse HIV testing, after adjusting for other individual-level predictors (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.15–3.85). This study demonstrated quantitatively that anticipations of HIV/AIDS stigma can be barriers to acceptance of HIV testing by pregnant women and highlights the need to develop interventions that address pregnant women’s fears of HIV/AIDS stigma and violence from male partners.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Stigma, Pregnancy, Kenya, Intimate partner violence

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, women comprise approximately 60% of adults living with HIV [1] and there is evidence that pregnant women have a higher risk of acquiring HIV infection than non-pregnant women [2, 3]. Vertical transmission of HIV from mother-to-child remains a significant problem in the region; UNAIDS estimates that 390,000 children in sub-Saharan Africa were newly infected with HIV in 2008—around 90% of the global burden of new pediatric infections [4]. This situation persists despite the fact that antenatal HIV testing and prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) interventions can reduce vertical transmission of HIV to as low as 1–2% [5]. In many countries, HIV testing is now routinely included in antenatal care (ANC) services, unless the pregnant woman explicitly refuses it [6, 7]. The promise of antenatal HIV testing and PMTCT programs has led UNAIDS to call for a “virtual elimination” of mother-to-child transmission of HIV by 2015 [1]. However, several challenges remain to achieving successful implementation and scale-up of these services. Although ANC services are visited by the majority of pregnant women at least once during pregnancy, in 2008 only 28% of pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa received an HIV test [1].

HIV/AIDS stigma is a common thread in the narratives of pregnant women affected by HIV/AIDS globally [8, 9]. Because a pregnant woman is often the first family member to be tested for HIV, she may be blamed for bringing the virus into the family and may suffer from adverse consequences of her HIV-positive status disclosure. Fears and experiences of stigma or discrimination from health workers, male partners, family, and community members have been identified as potential explanations for the facts that some pregnant women avoid maternity services altogether [10, 11], refuse antenatal HIV testing [12–14], or drop out of PMTCT programs once enrolled [15]. Theoretical frameworks and research on HIV/AIDS stigma also indicate that different dimensions of stigma—including anticipated stigma, perceived community stigma, enacted stigma, and self-stigma—adversely affect quality of life, healthcare access, and health outcomes [16–18]. Despite the consensus that HIV/AIDS stigma plays a significant role in deterring pregnant women from utilizing HIV services, few studies have attempted to quantitatively assess how these different dimensions of stigma affect uptake of HIV testing among pregnant women in high HIV prevalence settings.

Understanding women’s reasons for HIV test refusal is crucial for the development of interventions to increase antenatal HIV testing and extend the coverage of HIV services for pregnant women and their infants. We used data from the Maternity in Migori and AIDS Stigma Study (MAMAS Study) to examine how pregnant women’s perceptions of HIV/AIDS stigma influenced HIV testing uptake at ANC clinics in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Nyanza Province has the highest HIV prevalence in Kenya, with approximately 15% of adults 15–49 years of age testing HIV-positive [19]. Prevalence among pregnant women attending ANC clinics is higher, at an estimated 18% within districts included in this study (Family AIDS Care and Education Services program data [20]). In this manuscript we aim to a) describe the extent to which pregnant women who do not yet know their current HIV status perceive and fear HIV/AIDS stigma, and b) examine the relationships of quantitative measures of HIV/AIDS stigma to pregnant women’s refusal of HIV testing. In particular, we feel that it is important both theoretically and practically to understand the relative importance of different dimensions and sources of HIV/AIDS stigma—especially fears of stigma and negative consequences for self (anticipated stigma) versus general perceptions of stigma in the community (perceived community stigma)—for pregnant women’s uptake of HIV services.

Methods

The MAMAS Study

The MAMAS Study is a longitudinal study of pregnant women attending nine rural ANC clinics in Nyanza Province that aims to examine the effects of HIV/AIDS stigma on pregnant women’s use of health services. The study sites were government health facilities (four sub-district hospitals and five health centers/dispensaries), all receiving support from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief-funded Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES) for HIV prevention, care, and treatment efforts. All the sites were also part of an on-going cluster randomized trial of the integration of HIV services into ANC clinics (Clinicaltrials.gov # NCT00931216). This study received ethical approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethical Review Committee and the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco.

Pregnant women who did not know their current HIV status (never tested or tested negative more than 3 months ago) were recruited for the MAMAS Study, taken through a signed informed consent process, and interviewed just before their ANC visit by a trained interviewer using a questionnaire programmed on a small handheld computer (PDA). Additional inclusion criteria included the visit being her first ANC attendance for this pregnancy, being 18 years of age or older, and being at a gestational age of 28 weeks or less. Subsequently, all pregnant women were routinely offered voluntary HIV counseling and testing as part of the ANC visit (rapid testing) and, if they consented, information on their acceptance of HIV testing and their HIV serostatus were obtained from their medical records after their ANC visit. Recruitment and baseline interviews for the MAMAS Study took place between November 2007 and April 2009, although study activities were interrupted temporarily during the post-election period (January–March 2008). The current analyses use data from the baseline interviews of this longitudinal study.

Measures

Stigma and Discrimination Scales

HIV/AIDS stigma was measured using multi-item scales that have been developed and demonstrated to be valid and reliable in sub-Saharan African settings, as described below. These stigma scales were given to those participants who reported that they had heard of HIV/AIDS (98%), according to a preceding question.

“Anticipated stigma” refers to the anticipation that one will personally experience specific types of stigma or discrimination if one is found to be HIV-positive and one’s HIV-positive status is disclosed to others. A 9-item scale for measuring this construct was developed and tested in a study in Botswana [21]. In the scale items, a respondent is asked, “Do you think any of the following things might happen to you, if you were to test positive for HIV and others found out about your HIV status?” Items include losing friends, being treated like an outcast by the community, being treated badly at work or school, experiencing break-up of marriage or relationship, suffering from physical abuse by spouse/partner, losing one’s job/livelihood, being treated badly by health professionals, and/or being disowned or neglected by family. For each item, participants indicated whether they anticipated the event or not (Y/N response, coded 1/0). A total anticipated stigma score was created by taking the mean of the responses for the 9 items, for women who had non-missing data for at least 6 of the items. Reliability of this total score was found to be high in our sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) and a factor analysis revealed one underlying factor (data not shown). Variables were also created to examine anticipated stigma by source; we created dichotomous measures of anticipated stigma from the male partner (answered yes to either or both of the male partner items), from family members (answered yes to either or both of the family items), and from others (answered yes to one or more of the items regarding others).

In contrast, we also measured women’s general attitudes and perceptions about persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and how PLWHA are treated in the community, and we refer to this as “perceived community stigma”. We used the stigma scale developed by National Institute of Mental Health Project Accept to measure this construct [22]. The scale consists of 22 items, such as, “People who have HIV/AIDS are cursed” and “People living with HIV/AIDS in this community face ejection from their homes by their families”. Participants were asked to rate these statements on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The scale assesses three dimensions: negative attitudes and beliefs associated with PLWHA (negative attitudes, 8 items), perceptions of acts of discrimination faced by PLWHA within the community (discrimination, 7 items), and attitudes and beliefs related to fair treatment of PLWHA (equity, 4 items). The scale was previously tested in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Thailand, and the three sub-scales were found to have acceptable reliability [23]. Following the example of the scale developers, mean sub-scale scores were computed for women who had no more than one missing item in that sub-scale, and the mean total score was computed only for those who had valid scores on all three sub-scales. Scores on the scales ranged from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree); with negative items reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated higher perceptions of HIV/AIDS stigma. In our sample, reliability of the total stigma score, the negative attitudes sub-scale, the discrimination sub-scale, and the equity sub-scale were found to be 0.85, 0.78, 0.75, and 0.70, respectively (Cronbach’s α). Due to the relatively low reliability of the equity sub-scale, we did not use it in further analyses, similar to the approach of the scale’s authors [23].

Refusal of HIV Testing

Data on the women’s HIV testing uptake were obtained from clinic records after the woman’s ANC visit was completed. The woman’s situation was categorized as: (1) accepted testing, (2) refused testing, or (3) no HIV testing service available. For analyses with refusal of HIV testing as the outcome, only women who were actually offered HIV testing (HIV testing service was available at the facility on the day of their first ANC visit) were included.

Other Predictors of HIV Testing Refusal

Other individual-level variables examined (due to their associations with HIV testing refusal in theory or the literature) included the woman’s socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, gestational age, religion, marital status, polygamous relationship, occupation, and ethnicity), her knowledge of mother-to-child transmission, her knowing someone with HIV/AIDS, and her knowledge of husband’s/male partner’s HIV testing status. Knowledge of mother-to-child transmission and knowing someone with HIV/AIDS were hypothesized to be positively associated with HIV testing uptake, since women would be aware of the potential risks of HIV transmission and benefits of testing. Not knowing if the male partner had been tested for HIV was hypothesized to be negatively related to HIV test uptake, as an indicator of lack of couple communication on this issue, which has been shown to negatively affect women’s willingness to accept an HIV test [24]. Other variables included in the analyses were site (health facility where the woman was recruited and interviewed) and timing (months between study start date and interview date).

Analytic Methods

Psychometric properties of the HIV/AIDS stigma measures were assessed by calculating reliability (Cronbach’s α) for the total and sub-scales, and conducting factor analysis. Next, associations of stigma measures and other predictor variables with HIV testing refusal were examined by calculating unadjusted ORs and 95% CIs, while accounting for clustering by site (health facility). In order to be able to control for potential confounding factors, while accounting for clustering by site, we then ran a random effects multivariate logistic regression model [25] with site modeled as a random effect, including different HIV/AIDS stigma measures, as well as other individual-level predictors that had significance levels <0.05 in univariate analysis. Analyses were conducted with SPSS Statistics 17.0 and Intercooled Stata 9.0.

Results

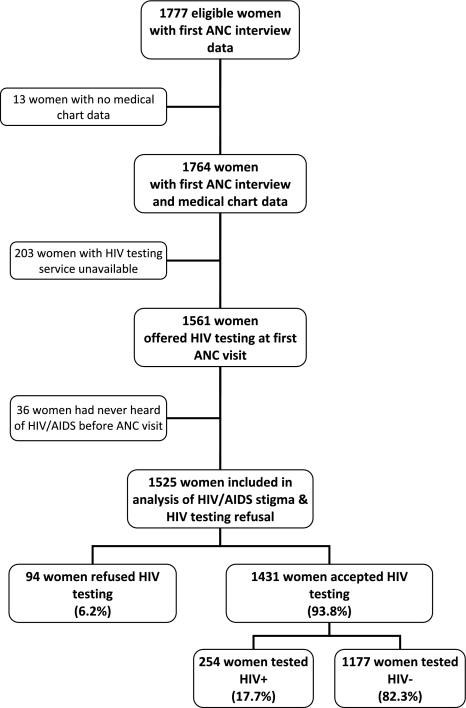

The refusal rate among women approached to participate in the study was 3.3% (67 women) and of those who enrolled in the study only nine women subsequently withdrew. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram for inclusion in the current analyses. The sample for our analyses of HIV/AIDS stigma and HIV test refusal includes 1525 women (86% of all women interviewed). The women in this group did not significantly differ from those not included (252) in terms of age, education, religion, marital status, ethnicity, months of pregnancy, or parity (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for inclusion in analyses of stigma and HIV test refusal

Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 presents the characteristics of pregnant women from the nine rural ANC clinics included in the current analysis (n = 1525). As reflected in the table, the majority of the participants were relatively young women (mean 23.6 years, SD = 5.4) of low socio-economic status (only 16% had more than a primary school education), Catholic or Seventh Day Adventist (52.2%), and of the dominant ethnic group in the study districts (92% were from the Luo ethnic group). Twenty-one percent of the women were experiencing their first pregnancy, while 36.3% had three or more previous pregnancies.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of MAMAS study participants included in the analysis (N = 1525)

| Age, n (%) | |

| ≤20 | 579 (38.0) |

| 21–30 | 767 (50.3) |

| ≥31 | 179 (11.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Only primary school (elementary) or less | 1277 (83.7) |

| Secondary school (high school) or more | 248 (16.3) |

| Reading literacy, n (%) | |

| Easily | 664 (43.5) |

| With difficulty | 616 (40.4) |

| Not at all | 245 (16.1) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Roman Catholic | 287 (18.8) |

| Seventh Day Adventist | 509 (33.4) |

| Other | 728 (47.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Luo | 1407 (92.3) |

| Other | 118 (7.7) |

| Household goods, n (%) | |

| Refrigerator | 16 (1.0) |

| Electricity | 56 (3.7) |

| Television | 159 (10.4) |

| Mobile phone | 723 (47.4) |

| Radio | 1149 (75.3) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Housework | 323 (21.2) |

| Selling things/fish monger | 329 (21.6) |

| Farming/agricultural work/manual labor | 772 (47.5) |

| Other | 147 (9.7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Not currently married | 188 (12.3) |

| Currently married | 1336 (87.7) |

| Currently living with male partner, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1331 (87.3) |

| No | 193 (12.7) |

| Male partner has other wives (n = 1331 women currently living with a male partner), n (%) | |

| Yes | 394 (29.6) |

| No | 937 (70.4) |

| Male partner’s occupation (n = 1330), n (%) | |

| Selling things | 142 (10.7) |

| Farming/agricultural work | 508 (38.2) |

| Fishing | 161 (12.1) |

| Manual labor | 205 (15.4) |

| Other type of job | 314 (23.6) |

| Mean months of pregnancy at time of first ANC visit (woman’s report) (median, range) | 5.1 (5, 0.4–9.0) |

| Mean number of pregnancies (median, range) | 3.2 (3, 1–16) |

| Mean number of live births (median, range) | 2.2 (2, 0–15) |

| Mean number of living children (median, range) | 1.8 (2, 0–10) |

HIV/AIDS Stigma

Tables 2 and 3 show levels of anticipated stigma and perceived community stigma for the women included in the present analyses. Rates of anticipated stigma associated with disclosure of HIV-positive status were very high—for example, 28% of women feared rejection by their family, 32% anticipated break-up of their relationship with their male partner, and 45% anticipated that they would lose their friends. Comparison of total anticipated stigma and perceived community stigma scores for women interviewed in the first 10 months of the study (approximately half the sample) with those interviewed later revealed that mean stigma scores were significantly higher in the earlier period (anticipated stigma: 0.2981 vs. 0.2676, t = 1.97, P = 0.049; perceived community stigma: 0.9133 vs. 0.7803, t = 6.79, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Anticipated HIV/AIDS stigma (N = 1525)

| Anticipated HIV/AIDS stigma item: Do you think any of the following things might happen to you, if you were to test positive for HIV and others found out about your HIV status? Do you think you would…? | Women responding “yes” n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Be treated badly by health workers (O) | 152 (10.0) |

| 2. Lose your job/livelihood (O) | 336 (22.0) |

| 3. Be denied care by family if sick (F) | 371 (24.3) |

| 4. Be rejected by family (F) | 432 (28.3) |

| 5. Be treated badly at work or school (O) | 466 (30.6) |

| 6. Be physically abused by your partner (P)a | 391 (25.6) |

| 7. Experience break-up of your relationship (P)b | 489 (32.1) |

| 8. Become a social outcast (O) | 513 (33.6) |

| 9. Lose your friends (O) | 688 (45.1) |

| Anticipated any stigma from male partner (P) (items 6 and/or 7) | 569 (37.3) |

| Anticipated any stigma from family (F) (items 3 and/or 4) | 563 (36.9) |

| Anticipated any stigma from others (O) (items 1,2,5,8, and/or 9) | 941 (61.7) |

| Mean combined anticipated stigma score (median, range) | 0.28 (0.22, 0–1) |

a46 Women (3.0%) refused to answer this question

b65 Women (4.3%) refused to answer this question

Table 3.

Perceived community stigma scale and sub-scales

| Scale or sub-scale | Number of items | Number of women with complete data | Mean | Median | Range (maximum possible score of 3) | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 18 | 1504 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0–2.39 | 0.85 |

| Negative attitudes | 7 | 1515 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0–2.86 | 0.78 |

| Perceived discrimination | 7 | 1509 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0–3.00 | 0.75 |

| Equity | 4 | 1523 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0–3.00 | 0.70 |

Sub-scales were constructed as in Genberg et al. [23], after excluding one additional item, “People with HIV/AIDS should not have the same freedoms as everyone else”. This item was dropped from the Total and Equity scales, due to very low correlation with the other scale items in this sample

HIV Test Refusal and Test Results

For those women who were offered HIV testing, refusal of an HIV test ranged from 16% in the early months of the study (March–May 2008), to 2% towards the end of the study (December 2008–February 2009), for an overall refusal rate of 6% for the entire study period. This trend in increasing acceptance of HIV testing by pregnant women at the study sites is also reflected in FACES program data for the districts (not shown). Of those study participants who accepted testing, 18% tested HIV-positive.

Predictors of HIV Test Refusal

Table 4 shows the associations of socio-demographic variables and other potential individual-level predictors with HIV test refusal, accounting for clustering by site. As can be seen in the table none of the socio-demographic characteristics examined were significantly associated with HIV test refusal. The woman’s lack of knowledge about her male partner’s HIV testing status and her not knowing anyone with HIV/AIDS were significantly and positively associated with HIV test refusal. In addition, those interviewed in the months closer to the study start date were significantly more likely to refuse HIV testing. The overall anticipated stigma score, as well as the combined measure of anticipated male partner stigma, were strongly associated with HIV test refusal, whereas neither the combined measures of anticipated stigma from family or others, nor any of the perceived community stigma total or sub-scales were significantly associated with HIV test refusal. Looking individually at the anticipated stigma items, those that were significantly associated with HIV test refusal were anticipations of break-up of relationship with partner (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.19–2.85, P = 0.006), physical abuse from partner (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.04–2.61, P = 0.032), neglect by family (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.13–2.68, P = 0.013), bad treatment by health workers (OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.2–3.69, P = 0.008), and losing job or livelihood (OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.10–2.73, P = 0.017).

Table 4.

Associations of predictor variables with HIV test refusal (Unadjusted) (N = 1525)

| Variable | HIV test refusers (N = 94) n (%)b |

HIV test acceptors (N = 1431) n (%)b |

OR for refusala | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| Mean age | 23.9 | 23.6 | 1.02 | 0.98–1.07 | 0.323 |

| Low education (only primary or less education) | 77 (81.9) | 1200 (83.9) | 0.73 | 0.40–1.33 | 0.307 |

| Currently married | 80 (86.0) | 1256 (87.8) | 1.01 | 0.53–1.94 | 0.966 |

| In a polygamous relationship | 23 (24.7) | 371 (25.9) | 0.88 | 0.52–1.48 | 0.639 |

| First pregnancy | 17 (18.1) | 309 (21.6) | 0.89 | 0.50–1.58 | 0.699 |

| Working in farming or manual laborc | 32 (34.4) | 690 (48.3) | 1.12 | 0.69–1.83 | 0.635 |

| Luo ethnic group | 91 (96.8) | 1316 (92.0) | 2.65 | 0.78–8.87 | 0.117 |

| HIV/AIDS stigma measures | |||||

| Anticipated stigma | |||||

| Anticipated stigma from partnerd | 47 (50.0) | 522 (36.5) | 2.07 | 1.29–3.33 | 0.002 |

| Anticipated stigma from familye | 45 (47.9) | 518 (36.2) | 1.53 | 0.96–2.42 | 0.074 |

| Anticipated stigma from othersf | 61 (64.9) | 880 (61.5) | 1.45 | 0.90–2.32 | 0.129 |

| Mean anticipated stigma combined score (n = 1511)g | 0.3499 | 0.2805 | 2.13 | 1.06–4.28 | 0.035 |

| Perceived community stigma | |||||

| Mean negative attitudes sub-scale (n = 1515) | 0.8346 | 0.7878 | 1.21 | 0.70–2.09 | 0.504 |

| Mean perceived discrimination sub-scale (n = 1509) | 0.8784 | 0.8967 | 0.86 | 0.47–1.56 | 0.614 |

| Mean total perceived community stigma score (n = 1504)h | 0.8414 | 0.8540 | 0.92 | 0.45–1.85 | 0.808 |

| Other individual-level predictors | |||||

| Mean months since the study began (Nov 20, 2007) | 8.99 | 10.66 | 0.91 | 0.86–0.97 | 0.003 |

| Knowledge of mother-to-child transmission | 74 (81.3) | 1256 (88.5) | 0.81 | 0.44–1.49 | 0.504 |

| Knows someone with HIV/AIDS | 63 (67.0) | 1109 (77.6) | 0.44 | 0.27–0.73 | 0.001 |

| Does not know if partner has tested for HIVi | 31 (33.0) | 308 (21.5) | 1.95 | 1.19–3.20 | 0.008 |

aEstimates account for clustering by site (health facility), using random effects logistic regression

bResults are presented as n(%) in these columns, unless otherwise indicated to be means. The denominators for percentages differ slightly in some cases, due to small numbers of missing responses

cAs compared to those working in housework, selling things (including fish), or other occupations (combined)

d72 Women refused to answer one or both of the anticipated partner stigma items

e35 Women refused to answer one or both of the anticipated family stigma items

f26 Women refused to answer one or both of the anticipated “other” stigma items

gMean anticipated stigma score was computed for women who had non-missing data for at least 6 of the 9 items

hMean perceived community stigma sub-scale scores were computed for women who had no more than one missing item in that sub-scale, and the mean total score was computed for those who do not have more than 1 item missing on any sub-scale

i22 Women refused to answer the question about her knowledge of her male partner’s HIV testing status

Multivariate Analysis of HIV/AIDS Stigma and Other Predictors on HIV Test Refusal

For multivariate analysis we used random effects logistic regression, with all estimates adjusted for months since study start, and accounting for clustering by site (health facility). In this adjusted model, anticipated stigma from the male partner remained strongly associated with HIV test refusal (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.15–3.85, P = 0.016), after adjustment for all the other variables in the model (Table 5). The other significant predictors from univariate analysis also retained their significant independent associations with test refusal after adjustment—those who knew someone with HIV/AIDS were less likely to refuse HIV testing (OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.31–0.89, P = 0.016), and those with lack of knowledge of their male partner’s HIV testing status were almost twice as likely to refuse testing (OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.05–2.99, P = 0.033). Measures of anticipated family stigma, anticipated stigma from others, and perceived community stigma were not significantly associated with the outcome in this model.

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression of HIV/AIDS stigma measures and other significant individual-level predictor variables on HIV test refusal (n = 1503)a

| Variable | Number of women in the category (n) | Adjusted OR for HIV test refusalb | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing someone with HIV/AIDS | ||||

| Doesn’t know anyonec | 349 | |||

| Knows someone | 1154 | 0.52 | 0.31–0.89 | 0.016 |

| Knowledge of male partner HIV testing | ||||

| Knows whether or not he testedc | 1152 | |||

| Doesn’t know whether or not he tested | 331 | 1.77 | 1.05–2.99 | 0.033 |

| Refused to answer | 20 | 2.45 | 0.64–9.35 | 0.191 |

| Anticipated stigma from male partner | ||||

| Noc | 879 | |||

| Yes | 565 | 2.10 | 1.15–3.85 | 0.016 |

| Refused to answer | 59 | 1.99 | 0.65–6.07 | 0.229 |

| Anticipated stigma from family members | ||||

| Noc | 919 | |||

| Yes | 558 | 1.02 | 0.54–1.92 | 0.954 |

| Refused to answer | 26 | 1.04 | 0.20–5.49 | 0.960 |

| Anticipated stigma from others | ||||

| Noc | 551 | |||

| Yes | 933 | 1.03 | 0.55–1.93 | 0.924 |

| Refused to answer | 19 | 1.14 | 0.16–8.21 | 0.895 |

| Total perceived community stigma score | 1503 | 0.62 | 0.28–1.39 | 0.247 |

a N is less than 1525 due to small numbers of missing values on individual variables

bAll estimates adjusted for time since the study began (categorical variable in 3-month chunks) and the other variables in the table. Estimates also account for clustering by site (health facility) as a random effect

cReference category

Discussion

Among women interviewed at their first antenatal clinic visit of the index pregnancy in selected government health facilities in Nyanza Province, Kenya, anticipated HIV/AIDS stigma from the male partner and lack of knowledge of the partner’s HIV status were found to be the main factors associated with refusal of HIV testing. We also found that women were more likely to accept HIV testing if they knew someone who was HIV-positive.

This study demonstrated that anticipated stigma regarding HIV/AIDS stigma can be a barrier to acceptance of HIV testing by pregnant women, even in an environment where HIV testing in the antenatal clinic is becoming the norm. Although refusal of HIV testing at the health facilities participating in this study declined from a high of 16% to only 2% of women by the end of the study, we would argue that even a small percentage of women refusing HIV testing is important in this high HIV prevalence setting. In a location where almost one in every five pregnant women is HIV-positive, every woman who refuses HIV testing represents an important missed chance to prevent mother-to-child transmission and promote maternal and child health. In many other settings in Kenya and other sub-Saharan African countries, high rates of refusal of HIV testing by pregnant women continue to be seen, and it is likely that HIV/AIDS stigma plays a role in these settings as well [14, 26].

We found that a woman’s specific fears of stigma and negative events for herself after an HIV-positive test result were important predictors of HIV test refusal—more important than her general perceptions of HIV/AIDS stigma experienced by PLWHA in the community. This corresponds with the psychological literature on stigma that suggests that anticipations of personal experiences of stigma and discrimination are stronger motivators of behavior than general perceptions of what happens to “other people” [27]. In addition, among the anticipated stigma items, we found that fears of stigma and discrimination from male partners were more important negative influences on HIV test acceptance than fears of stigma and discrimination from others (friends, family, co-workers, health workers, others in the community, etc.). Male partners can often have the biggest direct impact on the woman’s life and thus it is not surprising that fears about negative reactions from these influential close persons would be most predictive. Studies in other settings have also found stigma from partners and family to be influential [28]. Another important point is that HIV-positive pregnant women often appear healthy and do not disclose their HIV status [29]. Thus, their HIV status is not apparent to others and fears of stigma and discrimination from people in the wider community may be less salient.

We found that fears of negative male partner reactions (fear of domestic violence and rejection by one’s partner) and lack of knowledge about male partner HIV testing were the most important influences on women’s decision regarding HIV testing, in line with results from other East African settings [12, 13, 30]. While our analyses suggest that general perceptions of stigma related to HIV/AIDS may be declining over time in this population, it seems that gender norms and relations, as well as power dynamics within male–female relationships, are slower to change. An HIV-infected woman may face stigma from her male partner because he perceives that HIV/AIDS infection means that she has been promiscuous—thus violating the gender norm of female sexual faithfulness to a single male partner [31]. These perceptions lead to conflict in the couple, often resulting in negative consequences for the woman (such as rejection, abandonment, and/or violence).

These findings suggest that efforts need to be strengthened to encourage men to engage in a constructive way in their partner’s antenatal care, including HIV counseling and testing, in rural Kenya [24]. As in other similar settings, pregnant women often see partner consent and approval as an important condition for HIV testing acceptance [32, 33]. Solutions such as couple counseling and testing with facilitated disclosure [34], or if not possible, equipping women with skills for safe disclosure and partner communication about HIV/AIDS, need to be explored.

Although this study did not specifically examine reasons for the observed decrease in HIV testing refusal, we know that great emphasis was placed on encouraging HIV testing of pregnant women in Kenya during the study period. When the study began in 2007, the Migori and Rongo District Ministry of Health teams had newly begun their cooperation with FACES, with a mandate to strengthen PMTCT services. During the study period, the participating health facilities were strengthened through training, mobile team visits, and the employment of lay health workers and volunteers through FACES. Thus, the same trend of increasing HIV test acceptance was seen across the 60 clinics supported by FACES in these two districts. Despite the persistence of many barriers (including HIV/AIDS stigma), it appears that well trained and supported health workers are able to convince most pregnant women to accept HIV testing in this setting. A recent analysis of data on HIV test acceptance at ANC clinics in Kenya found that site factors were more important than participant factors in predicting HIV test acceptance among pregnant women [35].

The current study has some limitations. First, the study only included pregnant women who had at least one ANC visit and came for their first visit within the first 28 weeks of pregnancy. It is possible that women in the community who come for their first ANC visit later in pregnancy or who do not come for ANC at all may be most affected by HIV/AIDS stigma. Thus, our study may underestimate the effects of HIV/AIDS stigma on HIV test refusal. We are currently collecting community-based qualitative data to explore this issue further. In addition, our results may be subject to social desirability bias. Data on HIV/AIDS stigma were collected through face-to-face interviews, which may have resulted in underreporting.

Although it appears that HIV testing refusal may have declined in this setting, along with some reductions in HIV/AIDS stigma, the next important challenge for the future is what happens after an HIV-positive test result. In most sub-Saharan Africa settings, less than half of HIV-positive women receive PMTCT interventions and even fewer of these women enroll in HIV care and treatment for their own health [1]. Successful perinatal prevention of HIV requires women to navigate a cascade of events that begins with offering HIV testing and continues through enrollment in care and adherence to the prescribed antiretroviral regimen [36]. Even when women do accept HIV testing, high loss to follow-up in PMTCT programs threatens the public health potential of this model [37, 38]. Given the important role of anticipated HIV/AIDS stigma in refusal of HIV testing shown in this study, it will be important to examine the role of anticipated and experienced HIV/AIDS stigma in uptake of the services offered after HIV testing, as well as in uptake of other maternal child health services.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Kenyan women who participated in the study and shared their experiences with us. We acknowledge the important logistical support of the KEMRI-UCSF Collaborative Group and especially Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES). We thank the FACES CCHAs in Migori and Rongo for their diligent work in collecting the data. We gratefully acknowledge the Director of KEMRI and the Director of KEMRI’s Centre for Microbiology for their support in conducting this research. We also thank Katie Doolan, Nicole Kley, John Oguda, Abbey Hatcher, and Anna Leddy for their important contributions to this research. The project described was supported by Award Number K01MH081777 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Janet M. Turan, Phone: +415-597-9304, Phone: +650-322-2754, FAX: +415-597-9300, Email: Janet.Turan@ucsf.edu

Elizabeth A. Bukusi, Email: ebukusi@rctp.org

Maricianah Onono, Email: maricianah@yahoo.com.

William L. Holzemer, Email: bill.holzemer@rutgers.edu

Suellen Miller, Email: suellenmiller@gmail.com.

Craig R. Cohen, Email: CCohen@globalhealth.ucsf.edu

References

- 1.World Health Organization, UNAIDS, UNICEF. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector: Progress report 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/tuapr_2009_en.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2010.

- 2.Gray RH, Li X, Kigozi G, et al. Increased risk of incident HIV during pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1182–1188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moodley D, Esterhuizen TM, Pather T, Chetty V, Ngaleka L. High HIV incidence during pregnancy: compelling reason for repeat HIV testing. AIDS. 2009;23(10):1255–1259. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a5934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS, World Health Organization. AIDS Epidemic Update 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. 2009. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2010.

- 5.Lehman DA, John-Stewart GC, Overbaugh J. Antiretroviral strategies to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV: striking a balance between efficacy, feasibility, and resistance. PLoS Med. 2009;6(10):e1000169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassett MT. Ensuring a public health impact of programs to reduce HIV transmission from mothers to infants: the place of voluntary counseling and testing. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):347–351. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Cock KM, Marum E, Mbori-Ngacha D. A serostatus-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Africa. Lancet. 2003;362(9398):1847–1849. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond V, Chase E, Aggleton P. Stigma, HIV/AIDS and prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Zambia. Eval Program Plan. 2002;25(4):347–356. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(02)00046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorsen VC, Sundby J, Martinson F. Potential initiators of HIV-related stigmatization: ethical and programmatic challenges for PMTCT programs. Dev World Bioeth. 2008;8(1):43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Painter TM, Diaby KL, Matia DM, et al. Sociodemographic factors associated with participation by HIV-1-positive pregnant women in an intervention to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Cote d’Ivoire. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(3):237–242. doi: 10.1258/0956462053420158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turan JM, Miller S, Bukusi EA, Sande J, Cohen CR. HIV/AIDS and maternity care in Kenya: how fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):938–945. doi: 10.1080/09540120701767224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilewo C, Massawe A, Lyamuya E, et al. HIV counseling and testing of pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: experiences from a study on prevention of mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(5):458–462. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200112150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pool R, Nyanzi S, Whitworth JA. Attitudes to voluntary counselling and testing for HIV among pregnant women in rural south-west Uganda. AIDS Care. 2001;13(5):605–615. doi: 10.1080/09540120120063232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsson EC, Waiswa P, Thorson A, et al. Low uptake of HIV testing during antenatal care: a population-based study from eastern Uganda. AIDS. 2009;23(14):1924–1926. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832eff81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bwirire LD, Fitzgerald M, Zachariah R, et al. Reasons for loss to follow-up among mothers registered in a prevention-of-mother-to-child transmission program in rural Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(12):1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, et al. HIV-related stigma: adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–1177. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, et al. Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National AIDS and STI Control Programme. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, KAIS 2007, Final Report. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health, Kenya; September 2009, http://www.nacc.or.ke/2007/images/downloads/official_kais_report_2009.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2010.

- 20.Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES). Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission (PPCT) Summary Report. Kisumu, Kenya: KEMRI-UCSF. 2008. http://www.faces-kenya.org/updates/pdfs/2008_9-PMTCT-program-summary.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2010.

- 21.Weiser SD, Heisler M, Leiter K, et al. Routine HIV testing in Botswana: a population-based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genberg BL, Kawichai S, Chingono A, et al. Assessing HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination in developing countries. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):772–780. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orne-Gliemann J, Desgrees-Du-Lou A. The involvement of men within prenatal HIV counselling and testing. Facts, constraints and hopes. AIDS. 2008;22(18):2555–2557. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c54d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloh CE. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. New York, NY: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stringer EM, Chi BH, Chintu N, et al. Monitoring effectiveness of programmes to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(1):57–62. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: the impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(4):634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brickley DB, Le Dung Hanh D, Nguyet LT, Mandel JS, Giang le T, Sohn AH. Community, family, and partner-related stigma experienced by pregnant and postpartum women with HIV in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1197–1204. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9501-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visser MJ, Neufeld S, de Villiers A, Makin JD, Forsyth BW. To tell or not to tell: South African women’s disclosure of HIV status during pregnancy. AIDS Care. 2008;20(9):1138–1145. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antelman G, Smith Fawzi MC, Kaaya S, et al. Predictors of HIV-1 serostatus disclosure: a prospective study among HIV-infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS. 2001;15(14):1865–1874. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109280-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: an examination of the evidence. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(3):189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pignatelli S, Simpore J, Pietra V, et al. Factors predicting uptake of voluntary counselling and testing in a real-life setting in a mother-and-child center in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(3):350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bajunirwe F, Muzoora M. Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz DA, Kiarie JN, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, John FN, Farquhar C. HIV testing men in the antenatal setting: understanding male non-disclosure. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(11):765–767. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anand A, Shiraishi RW, Sheikh AA, et al. Site factors may be more important than participant factors in explaining HIV test acceptance in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in Kenya, 2005. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(10):1215–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killam WP, Tambatamba BC, Chintu N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in antenatal care to increase treatment initiation in HIV-infected pregnant women: a stepped-wedge evaluation. AIDS. 2010;24(1):85–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833298be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzi M, Zachariah R, Teck R, et al. High acceptability of voluntary counselling and HIV-testing but unacceptable loss to follow up in a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in rural Malawi: scaling-up requires a different way of acting. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(12):1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinkonde JR, Sundby J, Martinson F. The prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in Lilongwe, Malawi: why do so many women drop out. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17(33):143–151. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]