Abstract

Background

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) is a myocardial disease that predominantly affects the right ventricle (RV). Its hallmark feature is fibrofatty replacement of the RV myocardium. Apoptosis in ARVC/D has been proposed as an important process that mediates the slow, ongoing loss of heart muscle cells which is followed by ventricular dysfunction. We aimed to establish whether cardiac apoptosis can be assessed noninvasively in patients with ARVC/D.

Methods

Six patients fulfilling the ARVC/D criteria were studied. Regional myocardial apoptosis was assessed with 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy.

Results

Overall, the RV wall showed a higher 99mTc-annexin V signal than the left ventricular wall (p = 0.049) and the interventricular septum (p = 0.026). However, significantly increased uptake of 99mTc-annexin V in the RV was present in only three of the six ARVC/D patients (p = 0.001, compared to 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV wall of the other three patients).

Conclusion

Our results are suggestive of a chamber-specific apoptotic process. Although the role of apoptosis in ARVC/D is unsolved, the ability to assess apoptosis noninvasively may aid in the diagnostic course. In addition, the ability to detect apoptosis in vivo with 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy might allow individual monitoring of disease progression and response to diverse treatments aimed at counteracting ARVC/D progression.

Keywords: Arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy/dysplasia, Scintigraphy, Apoptosis, 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia (ARVC/D) is a disease that predominantly affects the right ventricle (RV), although biventricular involvement may occur in advanced disease [1]. ARVC/D is characterized by structural derangements that may cause a broad range of signs and symptoms. Yet, disease expression is highly variable and incomplete in most patients, confounding both the diagnostic process and clinical management, particularly during early disease stages [2].

The histopathological hallmark of ARVC/D is fibrofatty replacement of the RV myocardium. Apoptosis has been proposed as an important mechanism that mediates the slow, ongoing loss of heart muscle cells which is followed by ventricular dysfunction [3]. How fibrofatty replacement and apoptosis are related in ARVC/D is a matter of speculation. The possibility to detect apoptosis in vivo in ARVC/D may lead to a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanism underlying disease progression [4]. In vivo imaging of cardiac apoptosis with the use of 99mTc-annexin V has been proven feasible, as 99mTc-annexin V binds to exposed phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer surface of apoptotic cells [5]. Accordingly, 99mTc-annexin V has been effectively used to noninvasively visualize regions of apoptosis in patients with various pathologies [6–9], as well as in experimental models [10, 11]. We aimed to establish whether cardiac apoptosis can be assessed noninvasively in patients with ARVC/D.

Methods

Patients

The institutional review board approved the study protocol and informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. Six ARVC/D patients were examined. The patients, who fulfilled the ARVC/D Task Force criteria [12], were randomly taken from the cohort of ARVC/D patients at our institution. Patients were evaluated when they were in a clinically stable condition (no ventricular tachyarrhythmias or heart failure symptoms during the 2 months prior to inclusion). In all patients, molecular genetic analysis was performed and focused on known mutations related to ARVC/D; these included plakophilin-2 (PKP2), desmoplakin (DSP), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmocollin-2 (DSC2), plakoglobin (JUP), and transmembrane protein 43 (TMEM43) [13, 14]. No patient had a history of coronary artery disease, diabetes or hypertension.

Scintigraphy

Patients were intravenously injected with 600 MBq of 99mTc HYNIC-rh-annexin V (99mTc-annexin V), and 4 h after administration, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans were acquired using a dual-headed gamma camera equipped with a 3/8” NaI(Tl) crystal and combined with a low-dose CT scanner (Infinia; General Electric Medical Systems, Haifa, Israel). SPECT scans were acquired with low-energy, high-resolution collimators, a 15% energy window on the 140 keV photopeak, according to a step-and-shoot protocol with a total of 90 frames and 30 s per frame in a 128×128 matrix and a zoom of 1.28. SPECT images were iteratively reconstructed (OSEM) and corrected for attenuation using the low-dose CT scans from the Infinia scanner (no intravenous contrast material).

Analysis of scintigraphic data

To define the anatomical borders of the myocardium within the thorax, anatomical tomographic images are essential and the low-dose CT images of the Infinia could not be used for this purpose. Therefore, tomographic anatomical images from contrast-enhanced CT or cardiac MR imaging performed prior to implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation and within 2 months of 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy were reviewed for all subjects. To align the anatomical images with the SPECT data, first the matrix size of the anatomical images was adjusted to the matrix size of the SPECT data (128×128) and second the images were automatically aligned (MultiModality; HERMES Medical Solutions, Sweden). To semiquantify 99mTc-annexin V myocardial uptake, three regions of interest (ROI) including the RV wall, interventricular septum (IVS) and left ventricle (LV) free wall were drawn on three summed mid-myocardial horizontal long axis anatomical images. To correct for background activity (i.e. nonspecific uptake), a separate region was drawn on both lungs. As there were no differences between the two lung regions, these values were aggregated to one value (mean counts per pixel). The ROIs were determined on the anatomical images and were subsequently copied to the aligned SPECT images. 99mTc-annexin V uptake in each separate ROI was calculated as the ratio of the mean counts per pixel in the specific myocardial region to the mean counts per pixel in the total myocardium (i.e. the sum of all three ROIs). Both the regional and the total myocardial activity were corrected for background activity by subtraction of nonspecific uptake. The attenuation-corrected SPECT data were used for analysis. The reader was blinded to the clinical information.

Follow-up

Long-term follow-up data were obtained from at least one of three sources: visit to the outpatient clinic; review of the patient’s hospital records; personal communication with the patient’s physician. This analysis focused on the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias, appropriate ICD discharge, and sudden cardiac death. One patient was lost to follow-up. The mean follow-up was 27 ± 8 months (range 18–57 months).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Mean values were compared for differences using the (un)paired Student’s t-test when appropriate. For multiple comparisons, means were compared for differences using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc Bonferroni correction (SPSS for Windows 16.0.2.1; SPSS, Chicago, IL). A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Clinical spectrum

Table 1 summarizes the demographic/clinical data. All patients fulfilled the ARVC/D Task Force criteria [12]. Their mean age at clinical presentation was 36.7 ± 13.9 years (range 19–55 years) and 33% (two) were women. In five patients, ventricular tachycardia (VT) with left bundle branch block morphology was the first expression of ARVC/D. One patient presented with syncope. Two patients had a positive family history of premature sudden cardiac death. All patients had normal LV function by echocardiography and all patients had an ICD. All patients had a history of haemodynamically unstable VT. Four patients were on antiarrhythmic agents. One patient had the C796R mutation in PKP2, while one had the T335A mutation in DSG2. In the remaining patients, no DNA mutations were found. One patient (patient 6) had severe segmental dilatation of the RV on echocardiography (major ARVC/D Task Force criterion [12]). The other five patients had regional RV hypokinesia (patients 2, 3 and 5), mild segmental dilatation of the RV (patient 4) and mild global RV dilatation with normal LV function (patient 1) on echocardiography (minor ARVC/D Task Force criteria [12]).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with ARVC/D

| Patient no. | Gender | Age at scintigraphy (years) | Symptoms at diagnosis | Age at diagnosis (years) | Mutation | Medication | ARVC/D Task Force criteria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history | ECG depolarization/conduction | ECG repolarization | Arrhythmias | RV dysfunction | ||||||||||||

| Disease confirmed at necropsy (major) | Sudden cardiac death (minor)a | ARVC/D (minor) | Epsilon wave (major) | Late potential (minor) | Negative T wave (minor) | LBBB-VT (minor) | >1,000 PVC/24 h (minor) | Severe (major) | Mild (minor) | |||||||

| 1 | M | 24 | Syncope | 21 | PKP2: | Sotalol | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| C796Rb | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | F | 55 | VT | 49 | No | – | − | + | + | − | NA | + | + | − | − | + |

| 3 | F | 48 | VT | 38 | No | Sotalol | − | − | − | − | NA | + | + | NA | − | + |

| 4 | M | 33 | VT | 30 | No | Sotalol | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | NA | − | + |

| 5 | M | 19 | VT | 16 | No | Sotalol | − | − | − | − | NA | + | - | NA | − | + |

| 6 | M | 41 | VT | 27 | DSG2: | – | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | NA | + | − |

| T335Ac | ||||||||||||||||

LBBB left bundle branch block, NA not analysed, PVC premature ventricular complex.

aDeath before 35 years of age due to suspected ARVC/D.

bC796R missense mutation in plakophilin-2.

cT335A missense mutation in desmoglein-2.

Myocardial 99mTc-annexin V uptake

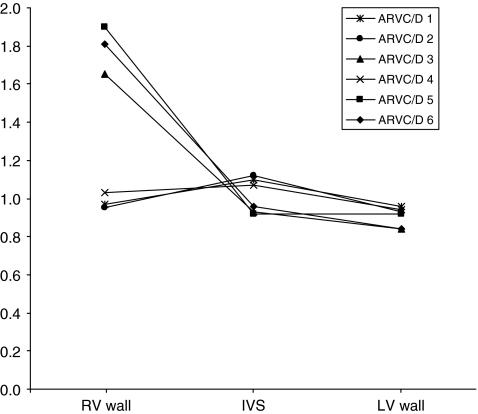

Figure 1 shows a typical example of a patient who exhibited increased 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV wall (patient 2). Overall, the RV wall showed a higher 99mTc-annexin V uptake (1.328 ± 0.437) than the LV wall (0.936 ± 0.175, p = 0.049) or the IVS (0.902 ± 0.222, p = 0.026). There was no difference in 99mTc-annexin V uptake between the LV wall and the IVS (p = 0.986). However, the overall higher uptake of 99mTc-annexin V in the RV wall could be explained by the fact that 50% of patients (patients 3, 5 and 6) showed increased 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV compared to the other three patients (patients 1, 2 and 4; 1.788 ± 0.133 vs 0.983 ± 0.034 respectively, p = 0.001; Fig. 2).

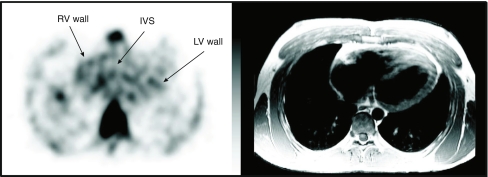

Fig. 1.

Coregistered transaxial images of patient 3 (left cardiac MR image, right 99mTc-annexin SPECT scintigraphy image). There is increased 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV wall (IVS interventricular septum, LV left ventricular free wall)

Fig. 2.

99mTc-annexin uptake in the RV wall, IVS and LV wall calculated as the ratio of the uptake (mean counts per pixel) in the vvparticular myocardial region to the uptake in the total myocardium (i.e. the sum of all three ROIs)

Within 2 months of 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy, cardiac MR images were available in three patients (patients 2, 3 and 4). Only patient 3 showed increased uptake of 99mTc-annexin V. The increased uptake of 99mTc-annexin V was located in the lateral wall of the RV, while the MR images showed an overall dilated RV with regional dyskinesia of the apex. It is therefore not possible to draw any conclusions as to a potential correlation between cardiac MRI RV abnormalities and the location of increased uptake of 99mTc-annexin V.

Follow-up

The extent of 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV wall did not distinguish patients with arrhythmias within 2 years after 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy from those without, nor did it distinguish patients in whom a gene mutation was found from those in whom it was not (Table 2).

Table 2.

Follow-up in ARVC/D patients on the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias, appropriate ICD discharge and sudden cardiac death

| Patient no. | 99mTc-annexin V uptake | Year of diagnosis | VT | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | VT | ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | VT | ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | VT | ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | VT | ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | VT | ICD shock | Sudden cardiac death | ||||

| 1 | Normal | 2001 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | Increased | 1998 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | - | − |

| 3 | Increased | 1994 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | Normal | 2001 | Lost to follow-up | |||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Increased | 2001 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | - |

| 6 | Normal | 1990 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | |||||||||

Discussion

Apoptosis is a significant pathophysiological feature of ARVC/D and is a consistent post-mortem finding in both the RV and LV [1, 15]. In this study, 99mTc-annexin V scintigraphy was performed with the purpose of establishing whether apoptosis can be visualized in vivo in patients with ARVC/D. Our results demonstrated increased 99mTc-annexin V uptake in the RV free wall of three ARVC/D patients, suggestive of RV-specific apoptotic activity in these patients. The variation in myocardial uptake of 99mTc-annexin V between patients is not surprising and might partly be explained by the random distribution and the episodic nature of the apoptotic process [16]. Furthermore, patients differed with respect to the time since diagnosis and severity of morphological abnormalities. These variations were probably reflected by differences in myocardial uptake of 99mTc-annexin V.

All our ARVC/D patients had a history of documented VT episodes. Mallat et al. speculated that apoptosis in ARVC/D might result from repetitive ventricular tachyarrhythmia episodes [15]. Furthermore, apoptotic myocytes are frequently found in regions of the myocardium which are not subjected to invasion by adipocytes and fibrosis, suggesting that the loss of myocytes through apoptosis occurs as a primary process before adipocytes and fibrous tissues fill the vacant cellular space. Also, Valente et al. have reported that apoptosis is present in endomyocardial biopsy samples of patients with ARVC/D, especially in the early symptomatic phase of the disease [17].

The exposure of PS on the cell surface is a general marker of apoptotic cells. Externalization of nonapoptotic PS is induced by several activation stimuli, including engagement of immunoreceptors. Externalized PS is observed in apoptotic, injured, infected, senescent and necrotic cells, and becomes a target for recognition by phagocytes [18–20]. Thus, in addition to acting as a marker of apoptosis, annexin V may be a marker of inflammation and cell stress. Accordingly, the myocardial uptake of 99mTc-annexin V is most likely not only a marker of apoptosis, but may also partly reflect local inflammation. Patchy inflammatory infiltrates in RV are consistently reported in ARVC/D, both in in vitro and in in vivo examinations [3, 21, 22].

Patchy cell death combined with inflammatory infiltration is a common histological finding in ARVC/D [23]. The inflammation might be a reaction to proinflammatory cytokines induced by cell death and/or apoptosis or caused by an infectious myocarditis (e.g. viral infection) [21, 24]. Although it is most likely that these factors are, at least to some extent, interrelated, it is not known whether there is a causal relationship between inflammation and cell death in ARVC/D. However, it remains unclear whether myocarditis in ARVC/D is disease-initiating (a primary event) or a reaction to processes initiated by ARVC/D.

Study limitations and clinical usefulness

The first limitation of our study is the small number of patients. The observation of 99mTc-annexin V myocardial uptake in three out of six patients might be explained by the random distribution and the episodic nature of the apoptotic process. Second, no cardiac biopsies were obtained. Therefore, a validation of the 99mTc-annexin V myocardial uptake with histology was not possible.

Recently modification of the highly specific ARVC/D Task Force criteria (published in 1994) has been proposed [25]. The revision incorporates new knowledge and technology to improve especially the sensitivity of the Task Force criteria without changing the high specificity. However, at the time of patient inclusion the 1994 criteria were used [12]. As expected, because of the relatively unchanged specificity, reevaluation of the patients included in our study according to the new criteria did not change the clinical diagnosis in any patient.

Conclusion

Apoptosis may be detected noninvasively in ARVC/D, and this may lead to a better understanding of the role of apoptosis in the pathophysiology of ARVC/D. Whether it will allow monitoring of the disease course or the response to various treatments aimed at counteracting disease progression remains to be studied.

Acknowledgments

Dr. H.L. Tan was supported by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, ZonMW-Vici 918.86.616).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- 99mTc

technetium 99m

- ARVC/D

arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia

- IVS

inter-ventricular septum

- LV

left ventricle

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- ROI

region of interest

- RV

right ventricle

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

References

- 1.Asimaki A, Tandri H, Huang H, Halushka MK, Gautam S, Basso C, et al. A new diagnostic test for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1075–1084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus FI, Zareba W, Calkins H, Towbin JA, Basso C, Bluemke DA, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation: results from the North American Multidisciplinary Study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:984–992. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basso C, Thiene G, Corrado D, Angelini A, Nava A, Valente M. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Dysplasia, dystrophy, or myocarditis? Circulation. 1996;94:983–991. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Heerde WL, Robert-Offerman S, Dumont E, Hofstra L, Doevendans PA, Smits JF, et al. Markers of apoptosis in cardiovascular tissues: focus on Annexin V. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:549–559. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00396-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankenberg FG, Katsikis PD, Tait JF, Davis RE, Naumovski L, Ohtsuki K, et al. In vivo detection and imaging of phosphatidylserine expression during programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6349–6354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofstra L, Liem IH, Dumont EA, Boersma HH, van Heerde WL, Doevendans PA, et al. Visualisation of cell death in vivo in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2000;356:209–212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02482-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofstra L, Dumont EA, Thimister PW, Heidendal GA, DeBruine AP, Elenbaas TW, et al. In vivo detection of apoptosis in an intracardiac tumor. JAMA. 2001;285:1841–1842. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kietselaer BL, Reutelingsperger CP, Boersma HH, Heidendal GA, Liem IH, Crijns HJ, et al. Noninvasive detection of programmed cell loss with 99mTc-labeled annexin A5 in heart failure. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:562–567. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.039453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narula J, Strauss HW. Invited commentary: P.S.* I love you: implications of phosphatidyl serine (PS) reversal in acute ischemic syndromes. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:397–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokita N, Hasegawa S, Maruyama K, Izumi T, Blankenberg FG, Tait JF, et al. 99mTc-Hynic-annexin V imaging to evaluate inflammation and apoptosis in rats with autoimmune myocarditis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:232–238. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campian ME, Verberne HJ, Hardziyenka M, de Bruin K, Selwaness M, van den Hoff MJ, et al. Serial noninvasive assessment of apoptosis during right ventricular disease progression in rats. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1371–1377. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.061366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna WJ, Thiene G, Nava A, Fontaliran F, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Fontaine G, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Task Force of the Working Group Myocardial and Pericardial Disease of the European Society of Cardiology and of the Scientific Council on Cardiomyopathies of the International Society and Federation of Cardiology. Br Heart J. 1994;71:215–218. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awad MM, Calkins H, Judge DP. Mechanisms of disease: molecular genetics of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:258–267. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, Connors S, French VM, Drenckhahn JD, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallat Z, Tedgui A, Fontaliran F, Frank R, Durigon M, Fontaine G. Evidence of apoptosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1190–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James TN. Normal and abnormal consequences of apoptosis in the human heart. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:309–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valente M, Calabrese F, Thiene G, Angelini A, Basso C, Nava A, et al. In vivo evidence of apoptosis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:479–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laufer EM, Reutelingsperger CP, Narula J, Hofstra L. Annexin A5: an imaging biomarker of cardiovascular risk. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirt UA, Leist M. Rapid, noninflammatory and PS-dependent phagocytic clearance of necrotic cells. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1156–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouckaert G, Kalai M, Krysko DV, Saelens X, Vercammen D, Ndlovu M, et al. Phagocytosis of necrotic cells by macrophages is phosphatidylserine dependent and does not induce inflammatory cytokine production. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1089–1100. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campian ME, Verberne HJ, Hardziyenka M, de Groot EA, van Moerkerken AF, van Eck-Smit BL, et al. Assessment of inflammation in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2079–2085. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabib A, Loire R, Chalabreysse L, Meyronnet D, Miras A, Malicier D, et al. Circumstances of death and gross and microscopic observations in a series of 200 cases of sudden death associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and/or dysplasia. Circulation. 2003;108:3000–3005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108396.65446.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basso C, Ronco F, Marcus F, Abudureheman A, Rizzo S, Frigo AC, et al. Quantitative assessment of endomyocardial biopsy in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: an in vitro validation of diagnostic criteria. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2760–2771. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calabrese F, Basso C, Carturan E, Valente M, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: is there a role for viruses? Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010;121:1533–1541. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]