Abstract

During prophase of meiosis I, genetic recombination is initiated with a Spo11-dependent DNA double-strand break (DSB). Repair of these DSBs can generate crossovers, which become chiasmata and are important for the process of chromosome segregation. To ensure at least one chiasma per homologous pair of chromosomes, the number and distribution of crossovers is regulated. One system contributing to the distribution of crossovers is the pachytene checkpoint, which requires the conserved gene pch2 that encodes an AAA+ATPase family member. Pch2-dependent pachytene checkpoint function causes delays in pachytene progression when there are defects in processes required for crossover formation, such as mutations in DS B-repair genes and when there are defects in the structure of the meiotic chromosome axis. Thus, the pachytene checkpoint appears to monitor events leading up to the generation of crossovers. Interestingly, heterozygous chromosome rearrangements cause Pch2-dependent pachytene delays and as little as two breaks in the continuity of the paired chromosome axes are sufficient to evoke checkpoint activity. These chromosome rearrangements also cause an interchromosomal effect on recombination whereby crossing over is suppressed between the affected chromosomes but is increased between the normal chromosome pairs. We have shown that this phenomenon is also due to pachytene checkpoint activity.

Key words: meiosis, double-strand break, Drosophila, crossing over, synaptonemal complex, pachytene checkpoint

During meiosis I, several associations are established between parental chromosome pairs including recognition, synapsis and recombination. These events are essential for the segregation of homologous chromosomes and formation of normal haploid gametes.1 Drosophila females are fairly typical in that recombination is initiated with a Spo11-dependent DNA doublestrand break (Fig. 1). The DSB is repaired by using the homologous chromosome as a template (homologous recombination) and can generate either crossover or non-crossover products. This occurs within the context of the synaptonemal complex (SC). The SC is a proteinaceous polymer with two parallel lateral elements held together by transverse filaments that join the homologous chromosomes along their entire length. In Drosophila, the SC is required for most crossovers,2,3 which manifest into the chiasmata that physically link the homologous chromosomes and direct their separation at anaphase.

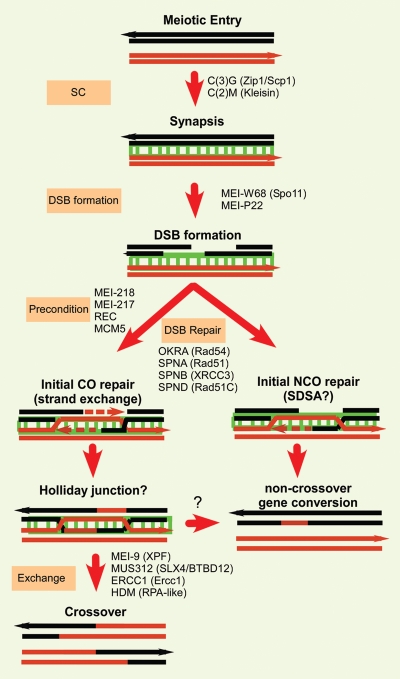

Figure 1.

Meiotic DSB repair pathway in Drosophila females. The Drosophila genes names are shown along with human homologs in parentheses. The SC (shown in green) forms independently of DSBs.24 The DSB repair genes are required for repair of all DSBs and the generation of both crossovers and noncrossover products. The suggestion in the figure, although not proven, is that the precondition genes enable the formation of an intermediate that can be resolved into a crossover.30 A Holliday junction is suggested in the Figure but other structures, such as an unligated intermediate, are possible. In the absence of the precondition genes, intermediates are made that can only become noncrossovers, possibly by an SDSA mechanism. The exchange genes resolve the precondition gene-dependent intermediates as crossovers. There must also be a pathway to get out of this intermediate as a noncrossover (shown by the “?”) to resolve recombination intermediates in exchange mutants.

Given the importance of crossovers in the process of chromosome segregation, it is not surprising that their number and distribution is regulated. This can be observed in several ways. First, the distribution of crossovers along each chromosome is not random. There are more crossovers in the middle third of the chromosomes and the frequency of crossing over is suppressed in regions closer to the centric heterochromatin (centromere effect). Second, the frequency of chromosomes without a crossover is lower than expected. Despite an average of only approximately 1.3 crossovers per chromosome, the frequency of X-chromosomes without a crossover is less than 5%.4 Third, the frequency of double crossovers is less than expected. This is due to the process of interference and reflects the observation that once a crossover site is established on a chromosome arm, additional crossovers in the vicinity (10–20 cM) occur less often. Finally, some mutants in Drosophila alter the distribution of crossing over, supporting the idea that the distribution as well as the frequency is under genetic control.5

Genes required for the repair of all meiotic DSBs encode homologs of Rad52 epistasis group proteins known to be involved in DSB repair in other systems. Two additional classes of Drosophila meiotic genes (exchange and precondition) are especially interesting since they are only required for crossing over (Fig. 1). The exchange class of genes may be directly involved in the part of the DSB repair pathway that generates crossovers. These genes appear to encode a protein complex based on the MUS312/BTBD12 protein.6 This complex includes the MEI-9 (an XPF ortholog) endonuclease and may function as a Holliday junction resolvase.7 If this complex is defective, as in mus312 or mei-9 mutants, noncrossover recombinants can still be generated and the small number of residual crossovers occurs with the same distribution as wild-type (e.g., less frequency towards the centromeres). Conversely, the precondition class of genes may be involved in a process that determines the number and distribution of crossovers. All four of these genes encode MCM-like proteins.8–10 Mutations in precondition genes not only reduce crossovers, but also affect the distribution. Essentially, the centromere effect is lost allowing an equal proportion of crossovers to occur distally as proximally. Therefore, this group of genes has been proposed to be involved earlier in the DSB repair pathway in a process that determines the subset of DSBs destined to become crossovers.

Checking your Axis at the Pachytene Checkpoint

Meiotic DSB repair during prophase is monitored by at least two checkpoints. First, the DSB repair checkpoint functions in meiotic and mitotic cells and monitors the repair of DSBs. In Drosophila females, defects in DSB repair trigger a delay in the oocyte developmental program, as if the meiotic program of DSB repair must be completed first. This process depends on the MEI-41 protein kinase, a homolog of ATR in mammals and leads to dorsal—ventral polarity defects in the developing embryo if meiotic DSBs fail to be repaired in the mother.11 The second checkpoint is referred to as the pachytene checkpoint and requires the conserved gene pch2, which encodes an AAA+ATPase family member. It was first discovered in budding yeast as being responsible for the pachytene delays observed in synapsis mutants.12 Similarly, a Pch2-dependent pachytene checkpoint causes apoptosis in C. elegans mutants with defective synapsis.13

We discovered that the Pch2-dependent pachytene checkpoint functions in Drosophila and delays pachytene progression in DSB-repair and exchange mutants.14 Indeed, DSB repair mutants induce two checkpoint responses, the DSB repair and pachytene checkpoints. Pachytene checkpoint responses includes a delay in the phosphorylation of H2AV, a chromatin response to DSBs,15 and a delay in choosing an oocyte among two pro-oocytes (Fig. 2). Unlike the checkpoint response in yeast and C. elegans, the Drosophila mutants eliciting checkpoint activity show no synapsis defects. As such, an important and unanswered question in all systems is the nature of the initial event(s) that triggers the checkpoint response. One common feature is striking; in all three organisms the checkpoint-dependent effects do not depend on DSBs.13,16 This was shown in Drosophila using mutations in the Spo11 homolog, mei-W68 and mei-P22, which are required for making meiotic DSBs. When a mutation in a DSB-repair or exchange gene is combined with a mutation in mei-W68 or mei-P22, oocyte selection delays are still observed. Insights into the underlying process that the checkpoint responds to may come from the analysis of the Drosophila precondition genes. Genes like mei-218 and rec are required for the pachytene delays in repair and exchange mutants,14 suggesting that precondition genes may be required for the signal which is detected by the pachytene checkpoint.

Figure 2.

Organization of the Drosophila Germarium. Region 1 is where the mitotic divisions occur to generate 16 cell cysts. In region 2a, each 16-cell cyst has two cells (pro-oocytes) in zygotene or pachytene. Oocytes can be identified by the SC (green), or cytoplasmic markers such as ORB (blue), although the SC is the most reliable and earliest visible marker. DSBs are generated in region 2a and can be detected by an antibody to phosphorylated H2AV15 (not shown). In region 2b and 3, the decision is made for one of the pro-oocytes to become a nurse cell. Pachytene checkpoint activity can be detected as delays in either the appearance and persistence of phosphorylated H2AV, the presence of two pro-oocytes in region 3 cysts14 or the persistence of Pch2 expression.17

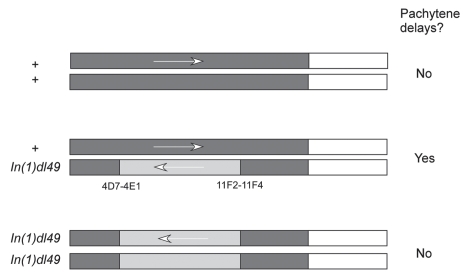

In our most recent work,17 defects in the meiotic chromosome axis were found to cause pachytene delays. Chromosome axis defects have been observed in two ways. First, mutants in genes that encode components of the chromosome axis, such as ord and c(2)M, cause a delay in choosing the winning pro-oocyte. Second, heterozygous chromosome rearrangements also cause Pch2-dependent pachytene delays (Fig. 3). For example, a single inversion or translocation heterozygote causes pachytene delays while the homozygotes do not. These results suggest that as little as two breaks in the continuity of the paired chromosome axes are sufficient to evoke checkpoint activity. Surprisingly, synapsis is not required for these checkpoint-induced effects. That is, delays in c(2) M mutants or inversion heterozygotes do not depend on the SC transverse element protein C(3)G. An interesting possibility is that, during meiosis, the homologous pairs of chromosomes interact by an SC-independent mechanism. If the chromosomes fail to align along their length, then axis defects may develop. Thus, a problem in homolog alignment may lead to defects in the organization of the chromosome axis, which then stimulates checkpoint activity and causes pachytene delays.

Figure 3.

Effect of inversions on pachytene delays. Pachytene delays are observed when chromosome rearrangements are heterozygous. The inverted part of the chromosome is shown in yellow. A pachytene delay occurs in c(3)G mutants and, therefore, do not depend on synapsis. The misalignment of two homologous chromosomes may be detected by a synapsis-independent pairing mechanism that may lead to defects in the axial structure of the chromosomes.

Is the Pachytene Checkpoint a Conserved Pathway?

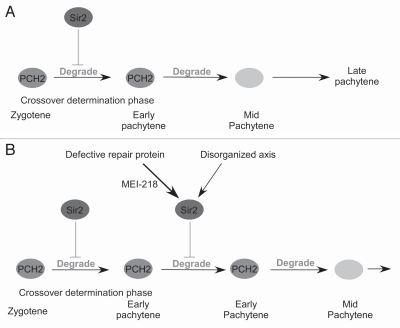

In budding yeast, the histone deacetylase Sir2 has been implicated in the pachytene checkpoint pathway.12 To look for evidence of a conserved pathway, we examined Drosophila sir2 mutants and found this gene to be required for the pachytene delays caused by repair mutants and axis defects.17 Thus, like pch2, the sir2 mutant is defective in the pachytene checkpoint, suggesting multiple components of the core pathway may be conserved. Where to place Sir2 in the checkpoint pathway relative to Pch2 (upstream or downstream) is not known. However, we have found that Sir2 is required for high levels of Pch2, suggesting that, when there is a defect that causes pachytene delays such as in the chromosome axis, Sir2 activity suppresses degradation of Pch2 prior to late pachytene (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Model for how the pachytene checkpoint regulates pachytene. A crossover determination phase allows the distribution and level of exchange per chromosome to be established, prior to and independent of DSB repair. PCH2 activity may regulate the crossover determination phase and restrict this time frame to the zygotene and early pachytene stages of prophase. (A) In wild-type, PCH2 is normally degraded prior to mid-pachytene, which turns off the checkpoint signal, ends the crossover determination phase. (B) Defects in DSB repair proteins or in the axis structure of the homologs cause Sir2 to prolong PCH2 activity, which extends the crossover determination phase and increases the chance of DSBs becoming crossovers. The increase in the number of crossovers could be due to the lengthening of this phase or altering the regulation of proteins that affect crossover formation.

An intriguing and possibly conserved link is between Pch2 and higher-order chromosome structure development. Synapsis and/or axis defects induce checkpoint activity in budding yeast, C. elegans and Drosophila. However, it is unclear why Drosophila c(3)G mutants fail to cause checkpoint-dependent pachytene delays while the homologous mutants in yeast and C. elegans do. Perhaps, in budding yeast and C. elegans, the role of central element components in synapsis is coupled to their role in axis alignment. In budding yeast, Pch2 may have a role controlling the assembly of the chromosome axes.18 Furthermore, defects in synapsis adversely affect crossover levels and may also affect the structure of the chromosome axis. In Drosophila, axis assembly may not depend on the SC since axis alignment can occur independent of synapsis. For example, ORD and C(2)M proteins localize in the absence of synapsis (in c(3)G mutants). In addition, the prominent somatic pairing in Drosophila may allow for meiotic homolog interactions that would not be possible in other organisms in the absence of synapsis. In the mouse, the link between Pch2 function and the chromosome axis is even more apparent. Mutations in the mouse pch2 homolog, Trip13, have defects in meiotic chromosome structure and recombination.19,20 Trip13 is also required for depletion of axis-associated HORMA domain proteins HORMAD1 and HORMAD2 as synapsis proceeds along meiotic chromosomes.21 The mouse Pch2 results also pose a striking difference compared to the other organisms; so far, there is no evidence of a checkpoint function for Trip13.

The results summarized above in both budding yeast and mouse show that loss of Pch2 can have defects in unperturbed meiosis. To help explain these mouse and budding yeast results, it has been proposed that Pch2 has two functions, one in a checkpoint pathway and the other in normal meiosis to regulate chromosome structure and recombination.20 In the context of this model, the mouse lacks the Pch2 checkpoint function while budding yeast has been proposed to have both. During budding yeast meiosis, pch2 seems to directly or indirectly affect the timing of DSB repair and recombination levels or distribution, as well as the checkpoint.18,22,23 In support of this argument is the observation in budding yeast that Pch2 localizes to two locations, the nucleolus and foci on the meiotic chromosomes. It is possible that the chromosome-localized Pch2 is required for the recombination function since in sir2 mutants, only the nucleolar localization is lost.12 Unlike the mutations in yeast and mice, meiosis in Drosophila and C. elegans seems to function normally in the absence of Pch2. Following the above model, Drosophila and C. elegans Pch2 may only have the checkpoint function during meiosis.

An alternative explanation to the distinct checkpoint and recombination functions of Pch2 may be that the pachytene checkpoint is important for the normal progression of meiosis. A potential unifying theme with Pch2 function in all organisms is the link with axial chromosome structure. Whether in a checkpoint role or in normal meiosis, Pch2 appears to integrate meiotic recombination with higher order chromosome structures. The difference between organisms with only a checkpoint mutant phenotype (Drosophila, C. elegans) and those with a recombination mutant phenotype (yeast, mouse) could be whether Pch2 is required to regulate normal meiosis. In some organisms, meiosis progresses without the need for timing adjustments by the Pch2 pathway. In other organisms, critical recombination and chromosome structure events may be poorly coordinated without the aid of the Pch2 pathway. Pch2 in yeast may be required to coordinate the timing of crossover formation and synapsis.16 This would explain why loss of pch2 function leads to effects on crossover number and distribution in some experimental systems and not others and why when crossover defects are observed, they can be temperature dependent.18 One model would be that early meiotic prophase in Drosophila and C. elegans is more efficient than in other organisms; that is, the pairing process may proceed so rapidly and reliably that the checkpoint is unnecessary under wild-type conditions. Several factors may contribute to the efficient interaction of homologous chromosomes. Both organisms form SC in the absence of DSBs.24,25 Homologous chromosomes pair efficiently in Drosophila somatic cells, which may enhance the pairing and synapsis process in meiotic cells. The duration of zygotene (the stage in which chromosome alignment is occurring) is rapid in Drosophila, estimated to occur within 12–24 hours (Joyce E and McKim K, unpublished). Similarly, pairing and synapsis of C. elegans homologs is aided by specialized pairing centers at one end of each chromosome.26 We suggest that the relative importance of the pachytene checkpoint under normal laboratory conditions may depend on the efficiency of homolog pairing and axis alignment.

Drosophila may have a unique second Pch2-dependent checkpoint pathway that monitors an early, as of yet unknown, function of repair proteins since this activity does not have an obvious parallel in other organisms. The DSB repair mutations cause a DSB-independent delay in oocyte selection similar to axis mutations.14,17 We have not determined if the repair mutations cause pachytene delays due to axis defects. However, an additional delay is also observed in the phosphorylation of H2AV, a chromatin remodeling response to DSBs. There are also differences in the requirements of the two types of inputs. The delays caused by the DSB repair and exchange mutants require the precondition genes whereas the delays caused by axis defects do not. Finally, while Pch2 expression persists longer in pachytene in both cases, the repair mutants also cause an increase in Pch2 levels.17 Assuming the two pathways converge, one needs to explain why exchange mutants cause delays in the DSB repair response but axis mutants do not. It is possible that these differences reflect when the defect is sensed or the intensity of the resulting signal. If the pachytene checkpoint is stimulated by a defect in an exchange mutant earlier in prophase or to a greater extent than in an axis mutant, then this could account for the differing effects on the phosphorylation of H2AV.

The Interchromosomal Effect on Crossing Over is Mediated by the Pachytene Checkpoint

The function of the pachytene checkpoint is not well understood. The function of checkpoints in general is to enable a cell to correct a problem before an irreversible event in the cell cycle occurs. We have found that there is more crossing over in exchange mutants such as hdm than in a hdm; pch2 double mutant.14 Thus, the pachytene checkpoint allows the meiotic cell to generate additional crossovers when there is a problem in the DSB repair pathway. We propose that the pachytene checkpoint in Drosophila delays meiotic progression when there are defects in the pathway to generate crossovers. The purpose of this delay is to enable the generation of more crossovers. This observation could be used to enhance genetic screens for meiotic mutants. Mutations that only mildly reduce meiotic crossing over may go undetected in genetic screens due to the robustness of the pachytene checkpoint and pch2 mutant flies may be an excellent sensitized genetic background in which to identify new meiotic mutants.

As noted above, heterozygosity for a chromosome rearrangement can cause pachytene delays. Since we have proposed that an effect of the pachytene checkpoint is to increase the number of crossovers, we hypothesized that it could be responsible for the interchromosomal effect. This is the observation that inversion heterozygosity, usually in the form of a balancer, suppresses crossing over on the affected chromosome but results in an increase in crossing over between the normal chromosome pairs. There has been a great deal of study on this phenomenon;27 however, the cause has not been determined. A model proposed by Lucchesi and Suzuki27 suggested an idea very similar to what we have proposed for the pachytene checkpoint. In inversion heterozygotes, the pairing process between homologs is perturbed, causing a delay in pachytene and an extended opportunity to make more crossovers. Because of the similarities between the interchromsomal effect and the pachytene checkpoint, we tested if pch2 is required for the increases in crossing over caused by heterozygous balancers. Indeed, we found that most of the extra crossovers found in balancer heterozygotes like FM7 and CyO were dependent on Pch2. Thus, it seems reasonable that the axis defects caused by balancer heterozygotes have several effects. They cause a suppression of crossing over on the affected chromosomes28 but also induce pachytene delays, which increases the number of crossovers on the unaffected chromosomes.

How the pachytene checkpoint facilitates more crossovers is not known. One possibility is that the delay extends a “crossover determination phase”. Since pachytene delays are associated with persistent expression of Pch2, such a crossover determination phase could be defined by the expression of Pch2 (Fig. 4).17 Interestingly, there is genetic evidence for a limited period of time in pachytene during which crossovers can be formed.29,30 We tested this possibility by overexpressing Pch2, which recapitulates the pachytene delays and extends Pch2 expression during checkpoint activation, yet only partially accrues the increase in crossover levels. Therefore, time is not the only crossover-promoting factor affected by checkpoint activation. Indeed, crossover sites may be determined during a short period around the time of DSB formation.31 This is consistent with the observation that the precondition genes function prior to DSB formation (Joyce E and McKim K, unpublished and reviewed in ref. 14).

An alternative is that checkpoint activity modifies proteins that regulate the total number of crossovers. Crossover patterns may be established and modified during a short time period, possibly independent of DSBs during the zygotene—pachytene transition. While the SC is required for crossing over in Drosophila, once it forms, it limits the number of crossovers to approximately one per chromosome arm due to interference. In addition to being defective in the pachytene checkpoint, we have found that sir2 mutants also exhibit an increased number of cells with visible SC in the 16 cell cysts (Joyce E and McKim K, unpublished). This result suggests that Sir2 activity may inhibit polymerization of SC components. Thus, in the presence of axis defects, an increase in Sir2 activity may cause a subtle decrease in the amount of C(3)G protein that is incorporated onto the meiotic chromosomes. Indeed, checkpoint activation was frequently associated with weaker C(3) G staining in late pachytene oocytes.14 A decrease in SC component incorporation may not be enough to affect the crossover promoting function of the SC, but may reach a threshold capable of attenuating the ability of the SC to limit the number of crossovers through interference or other mechanisms. Interestingly, a similar idea has been proposed from observing the effects of reducing the dosage of the C. elegans SC protein SYP-1.32 And predating our work and the recent C. elegans report was the finding that in c(3)G heterozygotes, which presumably make half the wild-type levels of protein, there is an increase in crossing over.33,34 Therefore, an inverse relationship exists between crossover numbers and the level of SC, which may be modulated by Sir2, presumably through histone deacetylase activity.

Future Directions

Perhaps one of the most important directions for the future is to elucidate the nature of the checkpoint pathway. The site of action of Pch2 checkpoint function is not known. In yeast, nucleolar localization of Pch2 depends on Sir2. We have observed that Drosophila Pch2 is associated with the outside of the nuclear envelope.17 In neither case, however, is this localization known to be essential for the checkpoint to function.12 We have found that the MCM-related precondition genes as well as Pch2 and Sir2 are required for the checkpoint, but it is not known if they function in a linear pathway or how they interact. Sir2 is intriguing because it raises the possibility that proteins can be found that are deaceylated as part of the checkpoint response. These may be proteins that are either involved in the timing of the meiotic program, crossover production or both. Interestingly, acetylation of cohesion proteins such as SMC3, which form part of the meiotic chromosome axis, is required for cohesion.35 Of equal importance will be identifying the upstream signals which activate the checkpoint. Our finding that axis defects cause pachytene delays suggest that checkpoint activity could be modulated by changes in chromatin structure. Additional clues to these mysteries may come from the discovery of proteins that interact with the AAA+ATPase Pch2. For instance, it will be of interest to see if these proteins are conserved and may help elucidate Pch2's mechanism of action. Pch2 seems to affect pachytene timing, but how is this controlled, and is there a crossover determination phase whose duration affects the frequency of crossovers? Finally, since the checkpoint affects crossover levels, insights may be found into what establishes the location and distribution of crossovers.

Acknowledgements

A fellowship from the Busch foundation to Eric F. Joyce and grant from the National Science Foundation to Kim S. McKim supported this work.

Extra View to: Joyce EF, McKim KS. Chromosome axis defects induce a checkpoint-mediated delay and interchromosomal effect on crossing over during Drosophila meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001059.

References

- 1.Hawley RS. Exchange and chromosomal segregation in eucaryotes. In: Kucherlapati R, Smith G, editors. Genetic Recombination. Washington, DC: American Society of Microbiology; 1988. pp. 497–527. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JC. Chromosome segregation influenced by two alleles of the meiotic mutant c(3)G in Drosphila melanogaster. Genetics. 1972;71:367–400. doi: 10.1093/genetics/71.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page SL, Hawley RS. c(3)G encodes a Drosophila synaptonemal complex protein. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3130–3143. doi: 10.1101/gad.935001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKim KS, Jang JK, Manheim EA. Meiotic recombination and chromosome segregation in Drosophila females. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:205–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041102.113929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter ATC, Sandler L. On recombinationdefective meiotic mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1974;76:453–475. doi: 10.1093/genetics/76.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen SL, Bergstralh DT, Kohl KP, LaRocque JR, Moore CB, Sekelsky J. Drosophila MUS312 and the vertebrate ortholog BTBD12 interact with DNA structure-specific endonucleases in DNA repair and recombination. Mol Cell. 2009;35:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein HL, Symington LS. Breaking up just got easier to do. Cell. 2009;138:20–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKim KS, Dahmus JB, Hawley RS. Cloning of the Drosophila melanogaster meiotic recombination gene mei-218: a genetic and molecular analysis of interval 15E. Genetics. 1996;144:215–228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanton HL, Radford SJ, McMahan S, Kearney HM, Ibrahim JG, Sekelsky J. REC, Drosophila MCM8, drives formation of meiotic crossovers. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:40. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lake CM, Teeter K, Page SL, Nielsen R, Hawley RS. A genetic analysis of the Drosophila mcm5 gene defines a domain specifically required for meiotic recombination. Genetics. 2007;176:2151–2163. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghabrial A, Schupbach T. Activation of a meiotic checkpoint regulates translation of Gurken during Drosophila oogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:354–357. doi: 10.1038/14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.San-Segundo PA, Roeder GS. Pch2 links chromatin silencing to meiotic checkpoint control. Cell. 1999;97:313–324. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhalla N, Dernburg AF. A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2005;310:1683–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1117468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce EF, McKim KS. Drosophila PCH2 is required for a pachytene checkpoint that monitors doublestrand-break-independent events leading to meiotic crossover formation. Genetics. 2009;181:39–51. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.093112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrotra S, McKim KS. Temporal analysis of meiotic DNA double-strand break formation and repair in Drosophila females. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu HY, Burgess SM. Two distinct surveillance mechanisms monitor meiotic chromosome metabolism in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2473–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyce EF, McKim KS. Chromosome axis defects induce a checkpoint-mediated delay and interchromosomal effect on crossing over during Drosophila meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi N, Barot A, Jamison C, Borner GV. Pch2 links chromosome axis remodeling at future crossover sites and crossover distribution during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:1000557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Schimenti JC. Mouse pachytene checkpoint 2 (trip13) is required for completing meiotic recombination but not synapsis. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roig I, Dowdle JA, Toth A, de Rooij DG, Jasin M, Keeney S. Mouse TRIP13/PCH2 is required for recombination and normal higher-order chromosome structure during meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojtasz L, Daniel K, Roig I, Bolcun-Filas E, Xu H, Boonsanay V, et al. Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:1000702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borner GV, Barot A, Kleckner N. Yeast Pch2 promotes domainal axis organization, timely recombination progression and arrest of defective recombinosomes during meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3327–3332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711864105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanders S, Alani E. The pch2Delta mutation in baker's yeast alters meiotic crossover levels and confers a defect in crossover interference. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:1000571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKim KS, Green-Marroquin BL, Sekelsky JJ, Chin G, Steinberg C, Khodosh R, Hawley RS. Meiotic synapsis in the absence of recombination. Science. 1998;279:876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dernburg AF, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, Villeneuve AM. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1998;94:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macqueen AJ, Phillips CM, Bhalla N, Weiser P, Villeneuve AM, Dernburg AF. Chromosome Sites Play Dual Roles to Establish Homologous Synapsis during Meiosis in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;123:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucchesi JC, Suzuki DT. The interchromosomal control of recombination. Ann Rev Genet. 1968;2:53–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherizen D, Jang JK, Bhagat R, Kato N, McKim KS. Meiotic recombination in Drosophila females depends on chromosome continuity between genetically defined boundaries. Genetics. 2005;169:767–781. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Jang JK, Kato N, McKim KS. mei-P22 encodes a chromosome-associated protein required for the initiation of meiotic recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2002;162:245–258. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhagat R, Manheim EA, Sherizen DE, McKim KS. Studies on crossover specific mutants and the distribution of crossing over in Drosophila females. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;107:160–171. doi: 10.1159/000080594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bishop DK, Zickler D. Early decision; meiotic crossover interference prior to stable strand exchange and synapsis. Cell. 2004;117:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi M, Mlynarczyk-Evans S, Villeneuve AM. The synaptonemal complex shapes the crossover landscape through cooperative assembly, crossover promotion and crossover inhibition during Caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. Genetics. 2010;186:45–58. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.115501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gowen MS, Gowen JW. Complete linkage in Drosophila melanogaster. Am Nat. 1922;61:286–288. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinton CW. Enhancement of recombination associated with the c3G mutant of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1966;53:157–164. doi: 10.1093/genetics/53.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidinger-Pauli JM, Unal E, Koshland D. Distinct targets of the Eco1 acetyltransferase modulate cohesion in S phase and in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2009;34:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]