Abstract

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates cell growth and metabolism in response to diverse external stimuli. In the presence of mitogenic stimuli, mTOR transduces signals that activate the translational machinery and promote cell growth. mTOR functions as a central node in a complex net of signaling pathways that are involved both in normal physiological, as well as pathogenic events. mTOR signaling occurs in concert with upstream Akt and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and several downstream effectors. During the past few decades, the mTOR-mediated pathway has been shown to promote tumorigenesis through the coordinated phosphorylation of proteins that directly regulate cell-cycle progression and metabolism, as well as transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in the oncogenic processes. The importance of mTOR signaling in oncology is now widely accepted, and agents that selectively target mTOR have been developed as anti-cancer drugs. In this review, we highlight the past research on mTOR, including clinical and pathological analyses, and describe its molecular mechanisms of signaling, and its roles in the physiology and pathology of human diseases, particularly, lung carcinomas. We also discuss strategies that might lead to more effective clinical treatments of several diseases by targeting mTOR.

Keywords: mTOR, rapamycin, lung cancer, molecular targeting therapy

Introduction

In the 1970s, a soil sample obtained from Easter Island (“Rapa Nui” in the native language) was found to contain a bacterial strain, Streptomyces hygroscopicus, that produced an antifungal metabolite. This metabolite was purified and found to be a macrocyclic lactone and named “rapamycin” after its birthplace. Subsequently, rapamycin (sirolimus) was found to exhibit immunosuppressive effects and to suppress cell proliferation [1], which spurred on further investigation into its properties and its target protein. The target was originally identified in yeast in the 1990s as a protein, a mutant of which confers resistance to the growth inhibitory effects of rapamycin, and thus designated TOR (target of rapamycin) [2, 3]. Simultaneously, the effect of rapamycin was shown to be dependent on an intracellular cofactor, the peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase, immunophilin FK506-binding protein 12 (FKBP12) [2]. Thus, TOR is also referred to as FKBP12-rapamycin associated protein (FRAP) [4, 5].

FKBP12 binds to the FKBP12-rapamycin binding (FRB) domain of TOR (Figure 1) [3, 4, 6, 7], and this complex inhibits the intrinsic kinase activity of TOR, including autophosphorylation, and inhibits access of TOR to its substrates [2].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the mTOR-signalling pathway from growth factor receptor through mTOR. Arrows represent activation, whereas bars represent inhibition. Abbreviations: PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; AMPK, AMP-activated kinase; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; Rheb, Ras homologue enriched in brain; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; FKBP12, immunophilin FK506-binding protein 12; FRB, FKBP12-rapamycin binding domain; 4E-BP1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; S6K, ribosomal p70 S6 kinase.

Mammalian homologue of TOR (mTOR), a component of catalytic complexes

Structure and profile

Every eukaryote genome contains a TOR gene. While some yeast species possess two TOR genes, higher eukaryotes possess only a single TOR gene, for example, mTOR (mammalian homologue of TOR) in mammals [2, 8].

TORs are a family of large proteins (- 290 kDa) that share 40%-60% identity, presumably reflecting the important role this protein plays in cell function [9]. The TORs form a group of kinases known as the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase (PIKK) family, which is characterized by the presence of a carboxy terminal serine/threonine kinase domain similar to that found in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K) [10]. The PIKK family of kinases possesses an FRB domain that lies amino terminal to the kinase domain and the members of this family are involved in basic cellular functions such as the control of cell growth, cell cycle and DNA damage checkpoints, and in the maintenance of telomere length [2]. As one of these members, the TOR acts as a central sensor for nutrient/energy, and is predominantly modulated by PI3K–Akt-dependent mechanisms (Figure 1). In response to mitogenic stimuli, mTOR positively regulates the translational machinery, accelerating events that promote cell growth [10, 11]. Accordingly, dysfunction of PIKK-related kinases results in a variety of disorders, ranging from immunodeficiency to cancer [9].

Two TOR complexes

Although there is a single mTOR gene in mammals, the mTOR product functions as a component of two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Figure 2) [3, 5, 12]. mTORC1 consists of mTOR, GβL/LST8 and regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (raptor), while mTORC2 consists of mTOR, GβL, and rapamycin-insensitive component of mTOR (rictor) [12]. Activation of either mTORC regulates protein synthesis and cell growth: rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 initiates translation in response to various stimuli and thus, regulates the timing of when a cell grows, (temporal regulation), while rapamycin-insensitive mTORC2 promotes a process whereby cells accumulate mass and increase in cell size and thus, regulates where a cell grows via re-organization of the actin network (spatial regulation) [2, 12]. When growing cells are treated with rapamycin, both mTORC1 and mTORC2 are depleted, leading to the down regulation of general protein synthesis, upregulation of macroautophagy and consequent activation of several stress-responsive proteins. Thus, mTORC1 signaling and also mTORC2 signaling, partially or indirectly, drive anabolic processes and antagonizes catabolic processes in a rapamycin-sensitive manner [2].

Figure 2.

Model of two mTOR signaling networks in mammalian cells: mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR Complex 2 (mTORC2) and their interacting proteins. mTORC1 mediates the rapamycin-sensitive signals determining the cell size. mTORC2 signaling is rapamycin insensitive and controls the actin cytoskeleton determining the cell shape. Upstream regulators of TORC2 are not clarified. Arrows represent activation, whereas bars represent inhibition. Abbreviations: PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; Rheb, Ras homologue enriched in brain; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; raptor, regulatory-associated protein of mTOR; rictor, rapamycin-insensitive component of mTOR; 4E-BP1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; eIF4E, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; S6K, ribosomal p70 S6 kinase; TOS, TOR signaling motif; rS6, 40S ribosomal protein S6.

Both mTOR complexes function predominantly in the cytoplasm. However, experiments using a nuclear export receptor inhibitor indicate that mTOR may actually be a cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling protein.This nuclear shuttling appears to play a role in the phosphorylation of mTORC1 substrates induced by mitogenic stimulation and in the consequent upregulation of translation [13]. This dual subcellular localization was also demonstrated by immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) in a study on human carcinomas (Chapter “mTOR and Lung Cancer”).

mTORC1: mTOR, raptor and GβL

Raptor, a component of mTORC1, is a 150-kDa protein that tethers the complex to its downstream effectors via a TOR signaling (TOS) motif found in mTOR substrates (Figure 2) [14]: p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) [15]. The raptor-mTOR interaction is nutrient-sensitive and is dependent on the presence of GβL which stabilizes raptor/mTOR binding and potentiates mTOR activity [16]. Through its interactions with these two partners, mTOR regulates cell growth, in part by phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K, and by the consequent phosphorylation of the far downstream molecule 40S ribosomal protein S6 (rS6) [16].

mTORC2: mTOR, rictor and GβL

Rictor, a component of mTORC2, is a protein of about 200 kD that contains no obvious catalytic motifs [17]. mTORC2 plays a role in reorganization of the cytoskeletal structure, and thereby determines the cell shape. Knockdown of rictor results in the loss of both actin polymerization and cell spreading [17]. mTORC2, in turn, modulates cell survival and proliferation by direct phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473. In this line, mTORC2 is proposed to be the putative 3-phospho-inositide-dependent protein kinase 2 (PDK2), and acts in association with PDK1 which phosphorylates Akt on Thr308 in vitro [18]. These phosphorylation events convert Akt to a fully activated state (Figure 2) [3, 12, 17]. FKBP12-rapamycin neither binds to nor affects the kinase activity of mTORC2 [17].

Physiological roles for mTOR

mTOR integrates a plethora of essential signaling pathways in response to diverse stimuli. For example, the increase in cell mass resulting from macromolecular biosynthesis and the increase in DNA content, both of which occur during each cell cycle, are regulated by mTOR. Indeed, homozygous mTOR−/− is an embryonic-lethal mutation in mice due to impaired cell growth [19]. Thus, mTOR is a conserved central coordinator of fundamental biological events, regulating many physiological events [20, 21].

Regulator of cell growth and early development

mTOR is one of the factors that coordinate the cell cycle transition. mTOR positively regulates the G1/S transition by suppression of cyclin D1 turnover [22], and by enhanced degradation of the cyclin dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor, p27 [1,23].

Moreover, mTOR, in particular mTORC1, contributes to the early development and differentiation/growth of lung acinar epithelium, chondrocytes, myocytes and adipocytes [21, 24-26]. In these tissues, mTOR mediates activation of the transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and regulates the glycolytic enzymes, leading to increased glucose uptake and glycolysis [27, 28]. This implies that mTOR may also play a role in the pathology of metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes.

Memory and aging

Rapamycin antagonizes long-term memory in mouse, synapse-specific long-term facilitation in Aplysia as well as cellular senescence in cultured cells. Thus, mTOR physiologically promotes long-term memory and senescence [2].

Autophagy and apoptosis

Under nutrient-starved conditions, cells can degrade cytoplasmic contents by the process of “autophagy”, whereby macromolecules are recycled within a vacuole called an autophagosome, presumably as a means to ensure survival [29]. mTOR negatively regulates the induction of this catabolic process by partially preventing the turnover of amino acid and glucose transporters [1, 30]. When mTOR is inactive, autophagy proceeds, and conversely, when mTOR is activated, the autophagic process is inhibited [29, 30].

mTOR also controls cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis. This involves mTOR phosphorylation and activation of S6K, which in turn binds to mitochondrial membranes, where it phosphorylates and inactivates the pro-apoptotic molecule BAD [31]. In addition, activated S6K has been reported to increase the apoptosis-inhibiting protein survivin [32], and to enhance degradation of the apoptosis-promoting protein PDCD4 (programmed cell death 4) [33].

Another indirect, but important downstream effector of mTOR is eIF4E, which functions as a positive regulator of cell survival. Unphosphorylated 4E-BP1 binds to eIF4E and suppresses its function (Figure 2) (Chapter “Translation”). In particular, 4E-BP1 undergoes caspase-dependent cleavage during apoptosis, and binds strongly to eIF4E, thus inhibiting cell survival [30, 34]. However, phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by mTOR results in its dissociation from eIF4E, which then becomes functionally active [15, 16]. Therefore, mTOR indirectly inhibits apoptosis by functional suppression of 4E-BP1, a promoter of apoptosis.

Transcription and ribosome biogenesis

The protein synthetic capacity of a cell depends on the amounts of ribosomes and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) present. Transcription of ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and tRNAs by RNA polymerases I and III account for as much as 80% of nuclear transcriptional activity and is tightly regulated by the mTOR pathway [35]. The activity of several other transcription factors, particularly those involved in metabolic and biosynthetic pathways, including signal transducer and activator of transcription -1 and -3 (Stat-1 and Stat-3)[36] and the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ [25], are also regulated by mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation in a rapamycin-sensitive manner.

Translation

All nuclear-transcribed, eukaryotic mRNAs contain a ‘cap’ structure, m7GpppN at their 5′ termini (‘N’ is any nucleotide and ‘m’ is a methyl group). This cap is specifically bound by the initiation factor eIF4E, which facilitates the recruitment of ribosomes to the mRNA [2, 3, 37]. 4E-BP1 dimerizes with eIF4E and blocks cap-dependent translation, but its phosphorylation by mTOR causes the release of eIF4E and promotes cap-dependent translation [38]. During this process, raptor mediates mTOR binding to 4E-BP1 through the TOS motif in 4E-BP1 (Figure 2) [21, 39].

mTORC1 also mediates phosphorylation of Thr389 in S6K1, leading to its activation and consequent phosphorylation of rS6. This results in the increased translation of a subset of mRNAs containing a 5′ tract of oligopyrimidine (TOP) that encode components of the translation apparatus, such as ribosomal proteins and elongation factors [40].

Actin organization

mTORC2 signal organizes the actin cytoskeleton via protein kinase C-α (PKCα), the small GTPases Rho and Rac, and thereby regulates cell motility [17]. Since rapamycin inhibits tumor cell motility, rapamycin may indirectly suppress rapamycin-insensitive mTORC2, in addition to mTORC1.

Angiogenesis

mTOR has been found to promote angiogenesis. This involves inhibitor of κB kinase-β (IKKβ), which activates the mTOR pathway and phosphorylates and inactivates the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/2), a complex that inhibits mTOR kinase activity (Figure 1) [41]. Downstream of mTOR, TSC1/2 activates HIF-1α, and subsequently upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production [9]. These sequential cascades drive the angiogenic process in both normal and tumor tissues.

Signaling cascades utilizing mTOR

As has been described, mTOR integrates various signals to regulate cell growth. mTOR lies at the interface of two major signaling pathways, one initiated by PI3K and the other by an energy-sensing pathway that involves serine threonine kinase 11 (also called LKB1) (Figure 1) [42, 43].

Physiological and pathological inputs

A number of biologically important stimuli have been shown to induce mTOR signaling: growth factors, nutrients (amino-acid, glucose and oxygen etc.), energy and stress [28].

First, binding of insulin or insulin-like growth factor (IGF) to its receptor (IGFR) leads to the recruitment and phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS). IGFR and IRS then interact with PI3K through specific phosphorylated tyrosine residues, which leads to the activation of mTOR [5].

Second, amino acids, in particular, leucine, enhance mTORC1 activation via inhibition of TSC1/2 or via stimulation of Ras homologue enriched in brain (Rheb), which is a small GTPase required for mTOR activation (Figure 1) [5, 14]. Arginine activates cell migration in a manner that is dependent on mTOR/S6K, but not on Erk1/2 in enterocytes [44].

Third, mTORC1 indirectly senses the energy status of the cell through the LKB1-mediated pathway, which functions in parallel to the PI3K pathway. LKB1, a tumor suppressor inactivated in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, activates AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) in response to energy deprivation (Figure 1) [42, 45]. This activation of AMPK in response to low cellular energy (high AMP/ATP ratio) downregulates energetically demanding processes, such as protein synthesis, and stimulates ATP-generating processes. Activated AMPK also phosphorylates and activates TSC2 by enhancing its GAP activity, resulting in the inhibition of mTORC1 [45]. Therefore, targeting AMPK may be a possible approach to cancer therapy.

Lastly, mTOR activity is repressed not only under conditions of energy deprivation, but also conditions of stress, such as hypoxia, heat shock, and low cellular energy state [2]. The hypoxic signal is transduced to mTORC1 via two homologous proteins REDD1 and REDD2, which are upregulated by HIF-1α. REDD acts downstream of PI3K and functions to inhibits mTORC1 signaling [2].

Upstream effector molecules of mTOR regulators

In response to the upstream inputs mentioned above, PI3K phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol -4,5-bis-phosphate (PIP2)to form phosphatidy-linositol-3,4,5,-trisphosphate (PIP3), which binds to Akt as well as PDK1 and facilitates their re-localization to the membrane. Akt is a member of the AGC [PKA/PKG/PKC] protein kinase family and regulates cell proliferation, survival, metabolism, and transcription [42, 46]. Co-localization of Akt with PDK1 results in the partial activation of Akt through phosphorylation at Thr308 [46]. Full activation of Akt requires additional phosphorylation at Ser473 by the putative kinase PDK2, which includes mTORC2 complex, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase and other kinases (Figure 2) [5, 47-49] Thus, mTORC2 performs a positive feedback role in the activation of Akt, and could thereby indirectly activate mTORC1. Akt suppresses the activity of the downstream TSC1/2 complex which otherwise inhibits the activity of Rheb [5]. This TSC1/2 complex functions as a key player in the regulation of the mTOR pathway by mediating inputs from the PI3K/PTEN/Akt and Ras/Erk1/2 signaling pathways, and by regulating translation initiation in response [3]. Activated Erk1/2 directly phosphorylates TSC2 at Ser664, (and possibly Ser1798 as well) [28, 50]. This site differs from those phosphorylated by Akt (Ser939, The1462 and possibly additional sites) [51], but either causes functional inactivation of TSC1/2 [2]. Of note, TSC2 is also a substrate of S6K [28].

Conversely, PIP3 accumulation is antagonized by the lipid phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10), which converts PIP3 to PIP2 (Figure 2) [3, 52]. Therefore, one critical outcome of PTEN inactivation is an increase in mTOR activity [3, 12]. Rheb, in turn, binds directly to the kinase domain in mTOR and drives the formation of that mTOR-Raptor complex in a GTP-dependent manner [53, 54].

Within mTOR, four phosphorylation sites have been identified: Ser1261, Thr2446, Ser2448 and Ser2481, the last being an autophosphorylation site [55]. While Ser1261 is the only site directly demonstrated to affect mTOR activity [56], subsequent phosphorylation of Ser2481 was also shown to correlate with the activation status of mTOR [57, 58]. Although phosphorylation at Thr2446/Ser2448 was shown to be PI3K/Akt-dependent, S6K, and not Akt itself, has been proposed to be the kinase responsible for phosphorylation of these two sites [59, 60]. The significance of this potential feedback loop is unknown, as it is not yet clear whether Thr2446/Ser2448 phosphorylation has a positive, negative, or no effect on mTOR function. Although Ser2448 phosphorylation by S6K is independent of Akt activation, it is blocked by rapamycin [60].

Although, to date, studies on the signal modulating functions of mTOR have focused on mTORC1, recent studies raise the possibility that mTORC2 is regulated similar to mTORC1. It has been shown that mTORC2 is involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and in cell migration [2, 17]. Furthermore, TSC1/2 regulates cell adhesion and migration [61], suggesting that mTORC2 may at least, partially act downstream of TSC1/2.

Downstream targets of the mTOR signaling network

mTORC1 phosphorylates S6K which also belongs to the AGC family of serine-threonine kinases and is implicated in the positive regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Full activation of S6K requires phosphorylation at two sites: Thr389, the target of mTORC1, and Thr229, the target of PDK1 [2, 3, 62]. Activated S6K, through activation of rS6, increases the translation of 5′-TOP mRNAs [40]. 5′-TOP mRNAs exclusively encode components of the translation apparatus, such as ribosomal proteins, elongation factors and IGF, and account for 15%–20% of total cellular mRNAs [3, 40].

4E-BP1 is phosphorylated at Thr35, Thr45, Ser64 and Thr69 by mTORC1, and these phosphorylations elicit eIF4E-mediated cap-dependent translation [38].

Regulatory loops by intricate mTOR network

Akt and mTOR are linked to each other via positive and negative regulatory circuits, which restrain their simultaneous hyperactivation (Figure 2). This system may have evolved as a safe-guard mechanism against deregulated cell survival and proliferation.

Negative regulation of IRS by S6K

A negative feedback loop leading from the mTOR-S6K1 pathway to the upstream IRS-PI3K-Akt cascade has been widely studied. Originally, loss of TSC1 or TSC2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts was found to inhibit insulin-mediated PI3K signaling [63]. This inhibition occurs as a result of PI3K inactivation via direct phosphorylation and inactivation of IRS by S6K, as well as by suppression of PI3K at the transcriptional level (Figure 2) [3, 64]. The benign nature of TSC-related tumors may be explained by the action of this negative feedback loop: although increased activity of mTOR and the downstream targets of Akt (GSK-3, FOXO, and others) initially fuels cell proliferation, subsequent feedback inhibition of Akt signaling acts to restrict tumor progression [28]. Consistently, one feature of rapamycin is that although it is quite potent in model systems, it exhibits only modest activity in the clinic [3, 64, 65]. One reason is that since rapamycin abrogates feedback inhibition through mTOR, it restores activity of Akt. This could pose a significant strategic dilemma when designing anti-cancer regimens using rapamycin, hence therapeutic approaches that simultaneously target both Akt and mTOR-raptor may ultimately prove more efficacious [28].

Feedback inhibition via mTOR is also relevant to the development of metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes. Under conditions where mTOR signaling is activated, for example due to deficiency in TSC or excess nutrients, the mTOR-mediated feedback loop dampens the duration and strength of IRS-PI3K signaling and thus leads to insulin resistance.

mTOR and disease

As we have seen, mTOR plays crucial roles in the processes of tissue development, morphogenesis, and organogenesis via an intricate network of signaling. Therefore, it is not surprising that deregulation of mTOR signaling is found in a variety of human disorders.

Non-neoplastic disease

Immunological Disorders: mTOR has been shown to activate T cells, which may explain the potency of the mTOR inhibitors sirolimus and everolimus as immunosuppressive agents in renal transplantation. These drugs have also shown promise in liver (sirolimus) and cardiac transplantation (everolimus), as well as in some autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and others [66].

Cardiovascular Disease: Cardiac hypertrophy caused by overgrowth of cardiomyocytes is dependent on the PI3K/mTORC1 pathway [52]. This finding prompted the testing of sirolimus in trials for cardiac hypertrophy. In addition, the use of intracoronary stents in the treatment of ischemic heart disease often causes smooth muscle cell hyperplasia surrounding the stent, a response that is also mediated through mTOR. This side effect frequently results in re-stenosis of the artery. These observations have led to clinical tests of sirolimus in drug-eluting stents for ischemic heart disease [67].

Metabolic Disorders: Both type 2 diabetes and obesity are associated with insulin resistance. Past studies have demonstrated that one of the causes is dysfunction of the IRS via a negative feedback loop from mTOR-S6K. Therefore, mTORC1 inhibitors may be useful for these particular types of metabolic disorders [63].

Cancer

General notions

It has recently been noted that constitutive PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation is critically involved in a variety of human cancers, including ovarian, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas [28, 68]. Activation of mTOR has been observed in leukemia [30], hepatocellular carcinoma [69], and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of head and neck (Table 1) [30, 70]. In particular, phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) immunoreactivity on tissue sections was reported in 63.5% of hepatocellular carcinoma, and significant association was found between p-mTOR expression and tumor size or metastasis [69].

Table 1.

Activation of the intermediate effectors in mTOR cascade in human malignancies

| Frequencies in lung cancer | References | Other tumors | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR | NSCLC ∼66% | 28, 68, 76, | Leukemia, liver head & neck | 69, 70, |

| SCLC ∼11% | 84, 85, 90 | kidney | 78, 80 | |

| S6K | NSCLC ∼58% | 84, 85 | breast ovary | 60, 73 |

| SCLC ∼20% | ||||

| rS6 | NSCLC ∼60% | 86,90 | sarcoma | 80 |

| SCLC ∼32% | ||||

| 4E-BP1 (inactivation) | NSCLC ∼25% | 90 | breast ovary endometrium | 38, 76,94 |

| SCLC ∼21% |

Cancer-related changes in mTOR kinase substrates include constitutive activation of S6K in ovarian tumor cell lines and in breast carcinomas (Table 1) [71-73]. eIF4E is elevated in cancers of the lung, bladder, head and neck, liver, colon and breast and leads to enhanced translation of VEGF, MYC and ornithine decarboxy-lase [3, 9, 74, 75]. By contrast, expression levels of 4E-BP1, a suppressor of eIF4E, are inversely correlated with the progression of breast cancer cells [9, 76]. Therefore, deregulation of the kinase-driven pathway involving Akt-mTOR-S6K/4E-BP1 plays a role in the pathology of many cancers. Indeed, rapamycin has clinically been approved for the treatment against renal cell carcinomas (RCC) and is currently being evaluated for other cancers [1, 77-79].

In addition to these reports, we have observed the unique involvement of mTOR in bone and soft tissue tumors. Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) of surgical specimens revealed that mTOR was expressed in 66%, and activated in 26% of sarcomas [80]. Among them, mTOR activation was frequently found in sarcomas of the peripheral nerve sheath (malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor), of skeletal muscle origin (rhabdomyosarcoma) and those exhibiting epithelial features (synovial sarcoma and chordoma) [80]. Thus, mTOR-mediated signaling may function in the differentiation and/or maintenance of morphological phenotypes of particular groups of mesenchymal tumors. Although mTOR/S6K normally integrates signals that promote growth and differentiation of chondrocyte, adipocyte and muscle cells [25, 26, 81], we did not observe frequent activation of mTOR in their tumor counterparts, except in tumors of skeletal muscle origin. Thus, the functional involvement of mTOR appears to be different in tumor versus normal tissue. Alternatively, mTOR may transiently function in a specific stage during oncogenesis.

Hamartoma syndromes

Hamartomas are benign tumors affecting various organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, brain, skin, kidneys and the lung. One underlying cause of hamartomas is aberrantly high activity of mTORC1 and its upstream and downstream signaling effectors [2, 52]. One representative of this syndrome is tuberous sclerosis, which results from mutation of TSC1/2. It is an autosomal dominant, multisystem disease characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas and benign or rarely malignant neoplasms distributed at various sites throughout the body, especially in the brain, skin, retina, kidney and the heart [2]. Preclinical studies have shown that the sensitivity of tumors in hamartoma syndrome to rapamycin analogues (rapalogs) correlate with aberrant activation of the PI3K pathways. Results of clinical trials showed that mTOR inhibitors are generally well tolerated and induce tumor regression in a subset of patients [1, 2].

mTOR and lung cancer

Activation profile of mTOR cassette proteins

Deregulated activity of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is one of the principal drivers in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). This is reflected in the fact that NSCLC as well as its cell lines frequently exhibit aberrantly active Akt and hyperphosphorylation of the mTOR-S6K-rS6 pathway [68, 82-86]. The final effector of this cascade, eIF4, can transform NIH 3T3 cells, and is overexpressed in SCC of the lung [87]. These findings support a molecular model whereby mTOR promotes tumorigenesis and/or progression by activation of the downstream eIF4 complex [3]. In addition, there have been several reports showing that higher activity of mTOR signaling more or less correlates with lymph node metastasis [83]. Thus, targeting the signal through the mTOR cassette proteins [Akt, mTOR, S6K, rS6 and 4E-BP1] and their upstream growth factor receptors, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), is a tantalizing idea for new cancer therapies. Further elucidation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathways, in particular, the activation profiles in different cancer types, may define molecular signatures for each case and facilitate the development of more effective mTOR-based therapies. To this end, to evaluate the activation patterns of effectors of the mTOR signaling cascade that function through S6K-rS6/4E-BP1 in the clinical cases of lung carcinoma, we examined the activation of mTOR signaling effectors by IHC and immunoblot analyses, and focused on the relationship of mTOR signaling to EGFR/Akt. These results, together with those from other reports, are summarized as follows (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of activation in the effectors of mTOR cascade in non-small cell lung carcinoma

| Histology | mTOR | S6-kinase | rS6 | 4E-BP1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | ∼90% | ∼73% | ∼73% | ∼23% |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | ∼40% | ∼28% | ∼42% | ∼24% |

| Large cell carcinoma | ∼60% | ∼43% | ∼71% | ∼43% |

p-mTOR: mTOR activation, evaluated by IHC staining for p-mTOR, was observed in 50-60% of all lung cancer cases, including 66% of NSCLC and 11% of small cell carcinoma (SCLC) [83]. Thus, mTOR activation is minimally involved in SCLC. The frequency of positivity and the staining pattern varied depending on the histological type. p-mTOR was positive in up to 90% of adenocarcinoma (AC), 60% of large cell carcinoma (LCC) and 40% of SCC cases (Table 2) [82-84]. Statistically, the frequency of p-mTOR-positive cases was significantly higher in AC compared to other types of NSCLC and significantly lower in SCLC. In addition, staining for p-mTOR was more intense in AC compared to other histological types, and was generally observed in the acinar structure of a well differentiated subtype (Figures 3 and 4), suggesting that mTOR plays a role in the morphogenesis or differentiation of the glandular structure [82, 83]. p-mTOR was observed exclusively in the cytoplasm in AC, but was observed in the nucleus in 25% of the SCC cases. This may reflect the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling behavior of the mTOR protein which has been described to be indispensable for activation of its substrates, S6K and 4E-BP1 [13, 88, 89]. This pattern of mTOR activation was confirmed by immunoblotting: p-mTOR, which migrated at approximately 289 kD, was generally more abundant in tumor tissue compared with adjacent non-neoplastic tissue, and was more abundant in AC compared to other histological types (Figure 5) [82].

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for activated mTOR (p-mTOR). Focally positive staining in a nest of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Intense p-mTOR staining in the acinar structure in adenocarcinoma (AC), and faint staining in large cell carcinoma (LCC). Rare positivity in small cell carcinoma (SCLC). Original magnification, ×100. Reproduced from “Critical and Diverse Involvement of Akt/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling in Human Lung Carcinomas” by Y. Dobashi, et al., Cancer. 115:107-118, 2009. Copyright John Wiley & Sons Limited. Reproduced and modified with permission.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining for proteins of the mTOR pathway. A case of adenocarcinoma (harboring mutation of L858R in EGFR) showed positive stainingfor activated mTOR (p-mTOR), p-S6K and p-rS6, but not for p-4E -BP1. All activated proteins were observed in the cytoplasm, but p-S6K positivity was also found in the nuclei, and p-4E-BP1 was observed in apoptotic cells (arrow). Original magnification, ×200. mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; 4E-BP1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; S6K, p70S6 kinase; rS6, 40S ribosomal protein S6. Reproduced from “Paradigm of kinase-driven pathway downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor/Akt in human lung carcinomas” by Y. Dobashi, etal., Human Pathology 42, 214-226, 2011. Copyright Elsevier Limited. Reproduced and modified with permission.

Figure 5.

Protein levels analyzed by immunoblotting analysis in representative cases. The intensity of the signals was expressed as ratios relative to β-actin, which was arbitrarily assigned a value of 10 (not shown in this Figure). In the case of p-4E-BP1, the faster migrating bands were subjected to quantification. Abbreviations: N, non-neoplastic tissue; T, tumor tissue; AC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SmCC, small cell carcinoma, mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; S6K, p70S6 kinase; rS6, 40S ribosomal protein S6; 4E-BP1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1. Reproduced from “Paradigm of kinase-driven pathway downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor/Akt in human lung carcinomas” by Y. Dobashi, et al., Human Pathology 42, 214-226, 2011. Copyright Elsevier Limited. Reproduced and modified with permission.

In contrast to the results obtained with tissue specimens, we did not observe significantly higher levels of p-mTOR in AC-derived cultured cells compared with SCLC- or SCC-derived cells (our unpublished data). Therefore, mTOR appears to be upregulated only in vivo in well differentiated AC, possibly because the cultured cells had lost the differentiated phenotype.

p-S6K: S6K activation was observed in up to 40% of the samples (43 to 58% in NSCLC and -20% of SCLC cases). Among the NCSLC cases, 52 to 73% of AC, 28% of SCC and 43% of LCC cases were positive [82-84]. p-S6K positivity was observed at a significantly higher frequency in the AC (p<0.05) [83]. Approximately, 50% of those positive cases showed nuclear staining, consistent with the idea that S6K also shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus [88]. Among the p-S6K positive NSCLC cases, 94% were p-mTOR positive, reflecting the close association between mTOR and S6K activities (Figure 4) [82, 83].

p-rS6: rS6 was activated in up to 56% of the cases (55-60% of NSCLC and 32% of SCLC). There was a higher prevalence of positivity in the AC and LC cases: 67 - 73% of the AC and -71% of the LCC cases were positive, while 42.0% was positive in SCC [82, 83, 85, 86]. p-rS6 positivity was observed to occur at significantly higher frequency in AC. The staining was almost exclusively cytoplasmic (Figure 4). However, tumor cells in the mitotic phase, regardless of histological type, occasionally exhibited positive staining. Among the p-rS6-positive NSCLC cases, 80% were also p-mTOR positive and 70% were p-S6K positive. This may indicate extensive “penetration” of the signal from mTOR to rS6. Immunoblot detection of p-rS6 was observed as a band of approximate 32 kD size, and was more frequently detected in AC compared to SCC cases, similar to what was observed by IHC (Figure 5) [83].

p-4E-BP1: 4E-BP1 activation was observed in 24% of the cases (25% of NSCLC and 21% of the SCLC cases) [83, 90]. We observed that 23% of the AC, 24% of the SCC, and 43% of the LCC cases exhibited positivity. The positive staining was almost exclusively cytoplasmic, but tumor cells in the mitotic phase and apoptotic cells occasionally exhibited positive staining, regardless of histological type (Figure 4). Among the p-4E-BP1-positive NSCLC cases, 64% were also p-mTOR positive. By immunoblotting, p-4E-BP1 was observed as a doublet of approximate 17 kD size. We observed little difference in p-4E -BP1 abundance among the different histological types, similar to the results obtained by IHC (Figure 5) [83].

These results overall suggest the potential utility of tailored therapies for lung carcinoma that would depend on the histological type. The mTOR pathway would appear to be an appealing therapeutic target since mTOR activation is significantly higher in well differentiated AC, and there exist established inhibitors, i.e. rapamycin. Indeed, the combined regimen of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) and an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) showed a synergistic effect in suppressing cell growth and motility in TKI-resistant cultured NSCLC cells [83, 90, 91].

Correlation between effector molecule phosphorylation and EGFR status

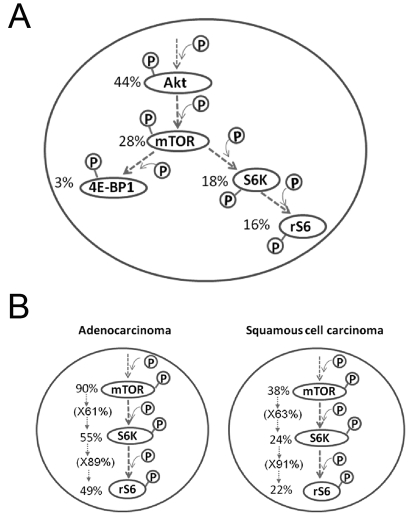

Based on the known relationships among effector molecules mediating mTOR intracellular signaling, we evaluated the staining patterns of interacting-mTOR cassette proteins by IHC (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

(A). Prevalence of activation of the intermediate effectors in Akt/mTOR-mediated pathway evaluated by immunohistochemistry. The values indicate positive ratios in total cases of all non-small cell lung carcinoma. (B). Activation of effectors in mTOR/S6K/rS6 pathway in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma evaluated by immunohistochemistry. The values indicate positive ratios in total cases. Abbreviations: mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; S6K, p70S6 kinase; rS6, 40S ribosomal protein S6; 4E-BP1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1.

p-Akt and p-mTOR: Akt is a principal positive regulator of mTOR and is activated in 44% of all cases (43 to 90% of the NSCLC and up to 50% of SCLC) [68, 83, 84]. Among the p-Akt-positive cases, 63% were also p-mTOR-positive. However, 68% of the p-Akt-negative cases also showed p-mTOR positivity [83, 90]. Within each histological type, mTOR was activated regardless of the status of Akt in AC. In SCC, 44% of the p-Akt positive and 32% of p-Akt negative cases were also positive for p-mTOR [83, 90]. Therefore, there was no clear correlation between Akt and mTOR activation in NSCLC, either as a whole or within each histological type.

p-mTOR and p-4E-BP1 or p-S6K/p-rS6: With regards to downstream effectors of mTOR, no clear correlation was found between p-mTOR and p-4E-BP1, and only 10% of the p-mTOR-positive cases showed activation of 4E-BP1 (Figure 6A). The correlation between p-mTOR and p-S6K activation was nearly identical among AC and SCC cases. Among the AC cases, 60% of p-mTOR-positive cases were p-S6K positive, while 90% of the p-S6K-positive cases were p-rS6-positive. Among the SCC cases, although only 38% were p-mTOR-positive, 63% of these p-mTOR-positive cases were p-S6K-positive and 91% of those p-S6K positive cases were p-rS6-positive. Thus, within both histological types, the signal emanating from mTOR is transduced to S6K in 60%, and to rS6 in 90% of those cases (Figure 6B). Constitutive activation of Akt-mTOR-S6K-rS6 was estimated to comprise 21% of the NSCLC and 16% of all cases of lung carcinomas (Figure 6A)[83].

Overall, mTOR was activated significantly more frequently in AC, up to 90% of the cases and a smaller fraction of the SCC cases. mTOR activation was independent of the activation status of its upstream molecules, and the downstream effectors S6K and rS6 were also activated more often in AC. The mTOR signal is mediated predominantly through S6K, and not through 4E-BP1, as reflected in the activation of each, 60% versus 10%, respectively. These results suggest that mTOR/S6K activation is involved in the differentiation, maintenance and possibly, the morphogenesis of a defined subset of lung carcinomas, in particular AC [2, 3, 44, 82]. Otulakowski et al. observed an enhanced p-rS6 signal throughout the lung epithelium after birth, suggesting that the S6K-rS6 cascade may play a critical role in the morphogenesis and/or acinar differentiation of lung epithelial structure [24]. This may explain the intense signal of the mTOR-S6K-rS6 axis seen in the glandular structure, including its cancer counterpart, AC (Figures 3 and 4) [82, 83]. Since 4E-BP1 expression has been observed in mesenchymal cells of the lung after birth [24], there is the possibility that the mTOR/4E-BP1 axis predominantly functions in non-neoplastic mesenchymal tissues.

Correlation with EGFR

It has been widely accepted that inappropriate signaling through EGFR is one of the principal drivers of lung cancer. In addition, activating mutations in the TK domain of EGFR have been found in up to 10% of NSCLC cases worldwide, and up to 40% within a defined Asian population [90, 92]. These cancers are very sensitive to TKIs [92]. In order to maximize the benefit derived from the suppression of EGFR signaling, many laboratories have undertaken analyses of the EGFR cascade and its role in lung carcinoma. Thus, we examined the status of EGFR and and the results obtained by IHC and immunoblotting for mTOR cassette proteins were combined with those genetic analyses. When the activation paradigm was evaluated in the context of EGFR/Akt as an upstream initiator, we observed that 18% of NSCLC cases exhibited activation of all three proteins, i.e. they simultaneously stained positive for p-EGFR, p-Akt and p-mTOR, which implies EGFR-Akt dependent mTOR activation (Figure 7A) [83]. Therefore, mTOR may be one of the essential downstream modulators of the EGFR-Akt cascade, although not an exclusive one [90]. When we focused on NSCLC cases harboring EGFR mutation, which were mostly AC, we observed constitutive activation of EGFR/Akt/mTOR in 67% of these cases (Figure 7B). The EGFR mutations were notably associated with higher levels of p-S6K and p-rS6 proteins: among overall cases of NSCLC, up to 54% showed activation of p-S6K and p-S6, but among those harboring an EGFR mutation, 90% showed activation [83, 85]. In contrast, activation of 4E-BP1 was observed in only 35%. Therefore, mutation of EGFR is associated in the majority of cases with constitutive activation of the Akt/mTOR/S6K/rS6 pathway, but not of p -4E-BP1 [83].

Figure 7.

Prevalence of activation in EGFR and representative intermediate effectors in Akt/mTOR-mediated pathway evaluated by immunohistochemistry. The values indicate positive ratios in total cases of non-small cell carcinoma (A) and in the cases harboring mutated EGFR (B). Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; rS6, 40S ribosomal protein S6.

With regards to the activation of entire cascade from EGFR/Akt/mTOR through rS6, constitutive activation of all the molecules was found in 12% with a slight preponderance in AC (Figure 7A). However, if we focus on tumors harboring mutations in the EGFR gene, we see constitutive activation of the entire cascade in 50% of the mutants (Figure 7B), and in 60% of the cases where the mutation results in potential TKI-sensitive phenotype (L858R, deletion around 746-750 in exon 19)[83, 85, 90]. This close correlation between EGFR mutation and activation of the cascade was observed even in SCC, although the numbers of SCC cases having a mutated EGFR were much smaller [83].

One notable observation in our study was the absence of activation in the Akt/mTOR/S6K axis in a tumor harboring the T790M mutation, which is known to be TKI-resistant. Although there was only one case examined, TKI-resistant mutants may transduce signals independent of mTOR, in contrast to TKI-sensitive mutants [83].

Clinicopathological analysis

The relationship between the activation of mTOR cassette proteins and clinicopathological features in NSCLC has been previously studied by IHC, but no consistent conclusion could be drawn. This may reflect the large variation in IHC data obtained. The clinicopathological correlations described in the literature to date are as follows.

i) There was a positive correlation between lymph node metastasis and mTOR phosphorylation in SCC, but not in other histological types [82]. Among the SCC cases, metastasis was more frequently observed in the p-mTOR-positive group (58%) versus the negative group (26%) at statistically significant level (p<0.05) [83]. A similar correlation between mTOR activation and lymph node metastasis was also described in gastric carcinoma [83, 93].

ii) Elevated p-S6 is associated with lymph node metastasis in AC, with a significantly shorter time-to metastasis compared with p-rS6 negative groups [83, 86].

It is unclear why lymph node metastasis is associated with mTOR activation in SCC, but with rS6 activation in AC.

iii) Activation of either p-4E-BP1 or p-S6K has been reported to correlate with poor prognosis in ovarian and breast carcinomas [38, 83, 94], and activation of S6K and/or 4E-BP1 was a determinant of cisplatin resistance in NSCLC [95]. Despite this, there was no predictive value in 4E -BP1 or S6K activation for nodal metastasis or overall survival in NSCLC [82, 83].

Taken together, these results show that activation of mTOR-mediated signaling confers clinical aggressiveness in a certain population, and more specifically that the signals that lead to rS6 activation may play a role in nodal metastasis in NSCLC [90].

mTOR kinase inhibitors and their clinical utility

The only specific small molecule inhibitors of mTOR reported to date are rapamycin and its derivatives. Rapamycin, an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, is a white crystalline solid that is insoluble in aqueous solutions, a property that has prevented development of a parenteral formulation [1]. Rapamycin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the 1990s as an immunosuppressant for use following renal transplantation. Rapamycin induces G1-arrest and/or delays in cell cycle transition [1], and in some cell lines, leads to apoptosis. The growth inhibitory effect of rapamycin is partially mediated by suppression of cap-dependent and 5′-TOP-dependent translation [5], but it also inhibits cdk activation and accelerates the turnover of cyclin D1 [22, 23](Chapter “Translation”). Moreover, rapamycin inhibits HIF-1α leading to decreased production of tumor-derived VEGF. It also indirectly affects tumor cells by suppressing the proliferation and survival of sustaintacular vascular smooth muscle cells [2, 5]. Rapamycin has also been shown to radiosensitize endothelial cells and enhance the pro-apoptotic effect of other cytotoxic agents on endothelial cells [96, 97]. In this sense, rapamycin exhibits an antiangiogenic effect [9, 98].

Collectively, these effects converge to suppress tumor cell growth and promote tumor cell death. The potent inhibitory activity of rapamycin has been demonstrated against cultured cells of glioblastoma, lung and pancreatic carcinomas, sarcoma, and other cell types [3, 30, 99, 100]. However, the poor chemical stability of rapamycin has limited its clinical use, and led to the development of three synthetic analogues (rapalogs) with superior pharmacokinetic properties [9]. The most notable analogues currently in use include CCI-779 (Cell Cycle Inhibitor-779, temsirolimus, Wyeth), RAD001 (40-O-[2-hydroxyethyl]-rapamycin, everolimus, Novartis Pharma AG), and AP23573 (Ariad Pharmaceuticals).

CCI-779 is a prodrug that is metabolized to rapamycin. It inhibits the growth of a wide range of cancer types and was assessed in phase I/II trials with escalating doses to determine the maximum tolerated dose level in solid tumors, such as RCC, NSCLC, glioblastoma, prostate, breast, and pancreatic carcinomas [9, 101, 102]. RCC yielded an objective response rate of 57%, and elicited a minor response or objective response in other tumors in more than 30% of the cases [9, 103, 104].

RAD001 has been approved for use as an immunosuppressant in solid organ transplantation. Since it also inhibits growth factor-stimulated proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, it could be another candidate agent in the drug-eluting stents against smooth muscle cell hyperplasia surrounding the coronary artery stent (Chapter “Cardiovascular Disease”). RAD001 was approved for the clinical use for metastatic RCC and a phase III study revealed significant effect in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [79]. Furthermore, it is currently being evaluated in a phase II clinical trial on patients with endometrial carcinomas, since these frequently harbor PTEN mutations [105]. In addition, the combination of RAD001 and imatinib is being evaluated in the phase I/II study in gastrointestinal stromal tumor [9].

AP23573 is the latest small molecule under development and is a phosphorus-containing compound and not a pro-drug [1]. Results of a phase II study reported significant activity in approximately 30% of previously-treated subtypes of sarcomas, including rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma [9, 77]. Currently, there are two large clinical trials examining the use of AP23573 on glioblas-tomas and sarcomas [9].

Taken together, promising results with rapalogs have been obtained in RCC, lung, and breast carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinomas, as well as minor responses in soft tissue sarcoma, uterine endometrial and cervical carcinomas [1, 28, 106].

Anti-cancer therapy utilizing mTOR inhibitors

It has long been recognized in the clinic that only a subset of patients in any given cohort derives significant benefit from a particular chemotherapeutic agent. Since these treatments sometimes expose many patients to side effects yet only help a few, it may be a worthwhile strategy to predict the tumor types and identify in advance who may respond to a specific therapy. Identification of the patients and tumors that can be successfully targeted by rapalogs will require: i) identification of optimal surrogate markers for assessing sensitivity or resistance, and ii) development of combinatorial regimens.

With regard to surrogate markers, clarification of the activation profiles of PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway may help in the selection of tumors that are most likely to respond. In particular, the phosphorylation status of S6K, rS6, and 4E-BP1 are promising markers for assessing the sensitivity to rapalogs, as well as monitoring their clinical efficacy [105, 107]. Loss of PTEN function with consequent activation of Akt, S6K, or 4E-BP1 has been found to be associated with objective responses to mTOR inhibitors, whereas low levels of Akt and S6K phosphorylation were associated with resistance to these inhibitors [42, 105]. Therefore, subgroups showing mTOR activation as assessed by these surrogate markers, irrespective of the status of upstream molecules, could be candidates for mTOR-targeted therapy.

With regard to combinatorial regimens, it will be important to define the combinations of rapalogs and conventional agents that are most effective on tumors in which mTOR cassette protein(s) are hyperactivated. For example, although mTOR signaling is both receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent and -independent, targeting mTOR in combination with anti-ERBB therapeutics for carcinomas of the lung, colon (EGFR), and the breast (ERBB-2), might lead to more profound effects than targeting either alone [10]. Synergistic effects of drugs and counter-measures against drug resistance are described in the next chapter.

Rationale for combination with rapalogs

Cancer is generally a heterogeneous disease involving activation of multiple pathways, and cases where cell proliferation is dependent on a single molecule are rare [10, 90]. Indeed, primary and acquired resistance to mTOR inhibitors was observed in several types of human cancers [1, 83] and this, together with negative signaling feedback (Chapter “Regulatory Loops by Intricate mTOR Network”), limits the efficacy of rapamycin in treating cancer [3, 65]. Moreover, when administered as a single agent, therapeutic doses of rapamycin need to be higher, with a consequent greater incidence of side effects.

mTOR is activated through various pathways emanating from a number of upstream elements, some of which are in turn down-regulated as a result of mTOR activation, comprising a negative feedback loop [28, 65]. Thus, mTOR inhibition combined with inhibition of its upstream signaling molecule(s) may have a greater therapeutic effect. Along this line, the combination of rapamycin and a PI3K inhibitor (e.g. XL147, Exelixis)[107] or Akt inhibitor (KP372-1, perifosine)[108, 109], are being investigated as the means to suppress rapamycin-induced Akt kinase activity, although each of those agents alone has limited efficacy due to lack of kinase specificity [65]. In addition, recent reports have described a dual-kinase inhibitor of PI3K/mTOR, PI-103 or NVP-BEZ235, which hold considerable promise [110, 111].

RAD001 can synergize with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and vinorelbine to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells [112], and can synergize with cisplatin to induce apoptosis in lung cancer cells {Petroulakis, 2006 #566}{La Monica, 2009 #1718}{Beuvink, 2005 #829}. Similarly, CCI-779 showed a synergistic cytotoxic effect on primitive neuroectodermal tumor cells when used in combination with cisplatin and camptothecin [9, 114]. Several TKIs have already been developed against NSCLC harboring mutated EGFR and the sensitivity to EGFR TKIs has been shown to be determined by the extent of inhibition in the Akt/mTOR/S6 pathway [83, 85, 90]. Thus, rapalogs may be useful in combination with EGFR-TKI against lung carciomas, in particular, those having EGFR mutation.

Theoretically, it may be possible to superimpose inhibition of the Akt/mTOR/S6K/rS6 axis by rapamycin with conventional regimens against any kind of malignant tumor in which the mTOR cassettes are constitutively activated [10, 90]. This type of expanded use of RAD001 has been demonstrated in combination with the EGFR/VEGFR inhibitor AEE788, which together exhibited a great suppressive effect on the growth of glioblastoma cells [3, 30, 115].

Future directions

The clinical benefit of targeted therapy against cancer is typically limited to a subset of patients, who in many cases are defined by a specific genomic lesion within their tumor cells, such as an activating mutation within the kinase domain [10]. However, the number of cancers that can be clearly characterized by specific genomic aberrations is not so large. Therefore, the use of rapalogs for molecularly targeted therapy is promising since the role played by mTOR in malignancy is multifaceted.

Ongoing clinical trials indicate that rapalogs show remarkable clinical potential in a variety of diseases. Although the anticancer effects of rapalogs may be augmented in combination with other agents, we must fully understand the pathways that regulate mTOR and how these intricate pathways are altered and how the upstream and downstream effectors are activated in each patient. Otherwise, mTOR inhibition could prevent the negative feedback loop and thereby exacerbate some pathological states. On the other hand, as noted in Chapter “Downstream Targets of the TOR Signaling Network”, the effectors downstream of mTORC1 themselves may also serve as potential drug targets. The molecular characterization of these downstream pathways will also facilitate the identification of markers useful for diagnosis, establishment of specific therapeutic regimens, disease prognosis and for monitoring the effects of rapalogs.

The mammalian cell contains roughly 600 kinases, suggesting that each kinase phosphorylates 20 substrates on average [2]. Consequently, we expect that additional mTOR substrates may be discovered, which may help us to better understand the mechanisms by which mTOR controls growth and help us develop novel mTOR inhibitors.

Just as the data from experimental models is used to inform the development of clinical strategies, we look forward to the results of clinical trials using rapamycin feeding back to the laboratory to further elucidate the roles of mTOR in cancer and to reveal hitherto unknown functions for mTOR in cancer.

References

- 1.Vignot S, Faivre S, Aguirre D, Raymond E. mTOR-targeted therapy of cancer with rapamycin derivatives. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:525–537. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petroulakis E, Mamane Y, Le Bacquer O, Shahbazian D, Sonenberg N. mTOR signaling: implications for cancer and anticancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:195–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fingar DC, Blenis J. Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 2004;23:3151–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmelzle T, Hall MN. TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell. 2000;103:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15:807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespo JL, Hall MN. Elucidating TOR signaling and rapamycin action: lessons from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:579–591. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.4.579-591.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janus A, Robak T, Smolewski P. The mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) kinase pathway: its role in tumourigenesis and targeted antitumour therapy. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2005;10:479–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR path way: a target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. An expanding role for mTOR in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JE, Chen J. Cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein is involved in rapamycin-sensitive signaling and translation initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14340–14345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011511898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proud CG. mTOR-mediated regulation of translation factors by amino acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schalm SS, Fingar DC, Sabatini DM, Blenis J. TOS motif-mediated raptor binding regulates 4E-BP1 multisite phosphorylation and function. Curr Biol. 2003;13:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Latek RR, Guntur KV, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol Cell. 2003;11:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami M, Ichisaka T, Maeda M, Oshiro N, Hara K, Edenhofer F, Kiyama H, Yonezawa K, Yamanaka S. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6710–6718. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6710-6718.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacinto E, Hall MN. Tor signalling in bugs, brain and brawn. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:117–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fingar DC, Richardson CJ, Tee AR, Cheatham L, Tsou C, Blenis J. mTOR controls cell cycle progression through its cell growth effectors S6K1 and 4E-BP1/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:200–216. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.200-216.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takuwa N, Fukui Y, Takuwa Y. Cyclin D1 expression mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase through mTOR-p70(S6K)-independent signaling in growth factor-stimulated NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1346–1358. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pene F, Claessens YE, Muller O, Viguie F, Mayeux P, Dreyfus F, Lacombe C, Bouscary D. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mTOR/P70S6-kinase pathways in the proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2002;21:6587–6597. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otulakowski G, Duan W, O'Brodovich H. Global and Gene-specific Translational Regulation in Rat Lung Development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0284OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JE, Chen J. regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity by mammalian target of rapamycin and amino acids in adipogenesis. Diabetes. 2004;53:2748–2756. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phornphutkul C, Wu KY, Auyeung V, Chen Q, Gruppuso PA. mTOR signaling contributes to chondrocyte differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2008 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pouyssegur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM. Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature. 2006;441:437–443. doi: 10.1038/nature04871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Autophagy in metazoans: cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:439–448. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B, Desai SA, MacCorkle-Chosnek RA, Fan L, Spencer DM. A novel conditional Akt ‘survival switch’ reversibly protects cells from apoptosis. Gene Ther. 2002;9:233–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaira V, Lee CW, Goel HL, Bosari S, Languino LR, Altieri DC. Regulation of survivin expression by IGF-1/mTOR signaling. Oncogene. 2007;26:2678–2684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang SK, Minai-Tehrani A, Lim HT, Shin JY, An GH, Lee KH, Park KR, Kim YS, Beck GR Jr, Yang HS, Cho MH. Decreased level of PDCD4 (programmed cell death 4) protein activated cell proliferation in the lung of A/J mouse. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23:285–293. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proud CG. The eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding proteins and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:541–546. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang CK, Liu H, Zheng XF. mTOR binds to the promoters of RNA polymerase I- and III-transcribed genes. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:953–957. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.5.10876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristof AS, Marks-Konczalik J, Billings E, Moss J. Stimulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1)-dependent gene transcription by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33637–33644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armengol G, Rojo F, Castellvi J, Iglesias C, Cuatrecasas M, Pons B, Baselga J, Ramon y Cajal S. 4E-binding protein 1: a key molecular “funnel factor” in human cancer with clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7551–7555. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Li W, Parra JL, Beugnet A, Proud CG. The C terminus of initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 contains multiple regulatory features that influence its function and phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1546–1557. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1546-1557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Li W, Williams M, Terada N, Alessi DR, Proud CG. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90(RSK1) and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 2001;20:4370–4379. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DF, Hung MC. All roads lead to mTOR: integrating inflammation and tumor angiogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:3011–3014. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.24.5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan X, Helman LJ. The biology behind mTOR inhibition in sarcoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:1007–1018. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-8-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhoads JM, Niu X, Odle J, Graves LM. Role of mTOR signaling in intestinal cell migration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G510–517. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00189.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, McCormick F, Tempst P, Coadwell J, Hawkins PT. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1998;279:710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toker A, Newton AC. Akt/protein kinase B is regulated by autophosphorylation at the hypothetical PDK-2 site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8271–8274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arvisais EW, Romanelli A, Hou X, Davis JS. AKT-independent phosphorylation of TSC2 and activation of mTOR and ribosomal protein S6 kinase signaling by prostaglandin F2alpha. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26904–26913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol. 2005;15:702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foster KG, Fingar DC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14071–14077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.094003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Acosta-Jaquez HA, Keller JA, Foster KG, Ekim B, Soliman GA, Feener EP, Ballif BA, Fingar DC. Site-specific mTOR phosphorylation promotes mTORC1-mediated signaling and cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4308–4324. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01665-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soliman GA, Acosta-Jaquez HA, Dunlop EA, Ekim B, Maj NE, Tee AR, Fingar DC. mTOR Ser-2481 autophosphorylation monitors mTORC-specific catalytic activity and clarifies rapamycin mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 285:7866–7879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caron E, Ghosh S, Matsuoka Y, Ashton-Beaucage D, Therrien M, Lemieux S, Perreault C, Roux PP, Kitano H. A comprehensive map of the mTOR signaling network. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:453. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiang GG, Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25485–25490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holz MK, Blenis J. Identification of S6 kinase 1 as a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-phosphorylating kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26089–26093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Astrinidis A, Cash TP, Hunter DS, Walker CL, Chernoff J, Henske EP. Tuberin, the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 tumor suppressor gene product, regulates Rho activation, cell adhesion and migration. Oncogene. 2002;21:8470–8476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pullen N, Dennis PB, Andjelkovic M, Dufner A, Kozma SC, Hemmings BA, Thomas G. Phosphorylation and activation of p70s6k by PDK1. Science. 1998;279:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manning BD. Balancing Akt with S6K: implications for both metabolic diseases and tumori-genesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:399–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, Picard F, Joaquin M, Sticker M, Fumagalli S, Allegrini PR, Kozma SC, Auwerx J, Thomas G. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2004;431:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature02866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, Lane H, Hofmann F, Hicklin DJ, Ludwig DL, Baselga J, Rosen N. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young DA, Nickerson-Nutter CL. mTOR-beyond transplantation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gershlick AH. Drug eluting stents in 2005. Heart. 2005;91(Suppl 3):iii24–31. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.060277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balsara BR, Pei J, Mitsuuchi Y, Page R, Klein-Szanto A, Wang H, Unger M, Testa JR. Frequent activation of AKT in non-small cell lung carcinomas and preneoplastic bronchial lesions. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2053–2059. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng Z, Fan X, Jiao Y, Ban K. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates expression of beta-catenin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molinolo AA, Hewitt SM, Amornphimoltham P, Keelawat S, Rangdaeng S, Meneses Garcia A, Raimondi AR, Jufe R, Itoiz M, Gao Y, Saranath D, Kaleebi GS, Yoo GH, Leak L, Myers EM, Shintani S, Wong D, Massey HD, Yeudall WA, Lonardo F, Ensley J, Gutkind JS. Dissecting the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling network: emerging results from the head and neck cancer tissue array initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4964–4973. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong AS, Kim SO, Leung PC, Auersperg N, Pelech SL. Profiling of protein kinases in the neoplastic transformation of human ovarian surface epithelium. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:305–311. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Couch FJ, Wang XY, Wu GJ, Qian J, Jenkins RB, James CD. Localization of PS6K to chromosomal region 17q23 and determination of its amplification in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1408–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Easton JB, Houghton PJ. mTOR and cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:6436–6446. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jones RM, Branda J, Johnston KA, Polymenis M, Gadd M, Rustgi A, Callanan L, Schmidt EV. An essential E box in the promoter of the gene encoding the mRNA cap-binding protein (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) is a target for activation by c-myc. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4754–4764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Leventaki V, Atwell C, Cho-Vega JH, Tian L, Claret FX, Rassidakis GZ. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway contributes to tumor cell survival in anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6589–6597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang H, Coleman J, Miskimins R, Miskimins WK. Expression of constitutively active 4EBP-1 enhances p27Kip1 expression and inhibits proliferation of MCF7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2003;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rowinsky EK. Targeting the molecular target of rapamycin (mTOR) Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:564–575. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000143964.74936.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pantuck AJ, Seligson DB, Klatte T, Yu H, Leppert JT, Moore L, O'Toole T, Gibbons J, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Prognostic relevance of the mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinoma: implications for molecular patient selection for targeted therapy. Cancer. 2007;109:2257–2267. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG, Tomassetti P, Pavel ME, Hoosen S, Haas T, Lincy J, Lebwohl D, Oberg K. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dobashi Y, Suzuki S, Sato E, Hamada Y, Yanagawa T, Ooi A. EGFR-dependent and independent activation of Akt/mTOR cascade in bone and soft tissue tumors. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1328–1340. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J. Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1472–1487. doi: 10.1101/gad.995802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dobashi Y, Suzuki S, Matsubara H, Kimura M, Endo S, Ooi A. Critical and diverse involvement of Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in human lung carcinomas. Cancer. 2009;115:107–118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dobashi Y, Suzuki S, Kimura M, Matsubara H, Tsubochi H, Imoto I, Ooi A. Paradigm of kinase-driven pathway downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor/Akt in human lung carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hiramatsu M, Ninomiya H, Inamura K, Nomura K, Takeuchi K, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Nakagawa K, Yamori T, Matsuura M, Morikawa T, Ishikawa Y. Activation status of receptor tyrosine kinase downstream pathways in primary lung adenocarcinoma with reference of KRAS and EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Conde E, Angulo B, Tang M, Morente M, Torres-Lanzas J, Lopez-Encuentra A, Lopez-Rios F, Sanchez-Cespedes M. Molecular context of the EGFR mutations: evidence for the activation of mTOR/S6K signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:710–717. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McDonald JM, Pelloski CE, Ledoux A, Sun M, Raso G, Komaki R, Wistuba, Bekele BN, Aldape K. Elevated phospho-S6 expression is associated with metastasis in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7832–7837. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, Rong L, Yoshida K, Ler LW, Sonenberg N. eIF4E–from translation to transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23:3172–3179. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ruvinsky I, Meyuhas O. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: from protein synthesis to cell size. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang X, Shu L, Hosoi H, Murti KG, Houghton PJ. Predominant nuclear localization of mammalian target of rapamycin in normal and malignant cells in culture. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28127–28134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dobashi Y, Koyama S, Kanai Y, Tetsuka K. Kinase-driven pathways of EGFR in lung carcinomas: perspectives on targeting therapy. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1714–1732. doi: 10.2741/3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]