Abstract

The control of mammalian mRNA turnover and translation has been linked almost exclusively to specific cis-elements within the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of the mature mRNA. However, instances of regulated turnover and translation via cis-elements within the coding region (CR) of mRNAs are accumulating. Here, we describe the regulation of post-transcriptional fate through trans-binding factors (RNA-binding proteins and microRNAs) that function via CR sequences. We discuss how the CR enriches the post-transcriptional control of gene expression, and predict that new high-throughput technologies will enable a more mainstream study of CR-governed gene regulation.

Key words: coding region, mammalian post-transcriptional gene expression, microRNAs, RNA-binding proteins, polysomes, translation, mRNA turnover

Introduction

In mammalian cells, a tight regulation of gene expression on multiple levels ensures proper responses to acute damaging agents, proliferative stimuli and developmental cues. Protein expression patterns are strongly influenced by a wide array of post-transcriptional processes affecting every aspect of mRNA metabolism, from its synthesis to its degradation.1–3 Among these processes, changes in the stability and translation of mature mRNA potently affect protein output. Two main types of mRNA-binding regulators have been implicated in the control of mRNA stability and translation: RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and noncoding RNAs, particularly microRNAs.

RBPs that regulate turnover and translation (sometimes named TTR-RBPs) associate with target mRNAs via different RNA-binding domains and regulate their stability and translation. Mammalian TTR-RBPs constitute a large family of proteins that includes human antigen (Hu) proteins [HuR (HuA), HuB, HuC, HuD], AU-binding factor 1 (AUF1), T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1) and TIA-1-related (TIAR) proteins, tristetraprolin (TTP), polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PTB), CUG triplet repeat RNA-binding protein (CUGBP), fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), the coding region determinant-binding protein (CRD-BP) and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP) A1, A2, C1/C2 (reviewed in ref. 4 and 5). The vast majority of these RBPs have been shown to affect mRNA turnover and translation by interacting with the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, and in some cases with the 5′UTR.3,6,7

MicroRNAs are ∼22 nt-long noncoding RNAs, which are loaded onto RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) that contain the Argonaute (Ago) RBPs as core components. In mammalian cells, they typically repress the translation of target mRNAs and/or destabilize mRNA by forming incomplete Watson-Crick base-paring.8,9 Like RBPs, almost all microRNAs have been reported to function by interacting with the 3′UTR of target mRNAs, but they occasionally interact with the 5′UTR.10–12 Through their influence on the production of proteins encoded by target mRNAs, both RBPs and RISC-loaded microRNAs have been implicated in important biological processes, including cell differentiation, cell cycle progression, carcinogenesis and the response to immune and stress stimuli.

As mentioned above, the UTRs provide fertile ground for regulation by both RBPs and RISC-bound microRNAs, sometimes binding individually, but often binding combinatorially. Thus, RBPs can compete or cooperate with other RBPs to elicit changes in mRNA abundance and/or translation;13,14 likewise, microRNAs can synergize with other microRNAs that interact with a shared target transcript.11 Recent examples are also emerging of functional interconnections (cooperative or competitive) between RBPs and RISC-microRNAs on shared UTRs.15,16

A small but growing number of studies indicate that RBPs and microRNAs elicit similar post-transcriptional gene regulation by interacting with coding region (CR) elements. Here, we review prominent examples of post-transcriptional gene control via the CR. With novel deep-sequencing methodologies for transcriptome analysis, we anticipate that much more regulation through the CR will soon come into view.

The UTR Bias

As the CR is the template for amino acid information and protein biosynthesis, this mRNA region was widely considered to be the exclusive domain of ribosomes. Accordingly, the past two decades' efforts to identify cis-elements of post-transcriptional control focused on the 5′UTR and the 3′UTR. In the 5′UTR, several regulatory motifs have been described, for example the polypyrimidine tract, the internal ribosome entry site (IRES), the iron response element (IRE), and the 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine (5′TOP) tract (reviewed in ref. 6); several sites of interaction with microRNAs have also been reported in the 5′UTR.10–12 In the 3′UTR, translation and stability are governed by sequences such as the cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements (CPEs), U- and AU-rich elements (AREs), GU-rich elements (GREs) and other elements rich in CUGs, CUs, etc.17–19 Additionally, the vast majority of mammalian microRNAs described have been shown to function through binding to 3′UTR sequences.8

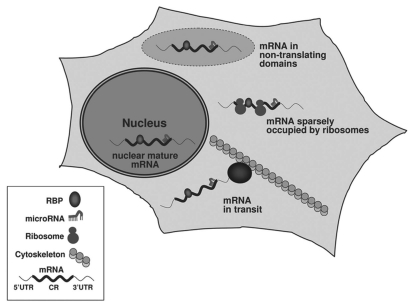

While the CR has received less attention, much of the cellular mRNA is in fact excluded from polysomes (e.g., nuclear mRNAs and cytoplasmic mRNAs in transit or storage) or is occupied sparsely by ribosomes20,21 (Fig. 1). Therefore, the non-translating mRNA pool and mRNA segments are available for interaction by RBPs and noncoding RNAs. The resurgence in interest in CR regulatory elements is largely driven by the recent discovery of CR-directed microRNAs, although several RBPs that function through target CR sequences have also been identified. Below, we discuss several reports of CR-directed trans-binding factors (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CR-bound RBPs and microRNAs in the mammalian cell. RBPs and microRNAs may be found associated with mRNAs during transport, while mRNAs are stored in specialized cytoplasmic locales (e.g., stress granules or processing bodies), or in polysomes with low ribosome occupancy. Mature mRNAs may also associate with RBPs and microRNAs in the nucleus.

Table 1.

mRNAs regulated through the CR

| Factors | Target mRNAs | Regulators | Function | References |

| CR-binding RBPs | APP | hnRNPC FMRP |

Translation ↑ Translation ↓ |

31 30, 31 |

| β-TrCP | CRD-BP (1) | Stability à | 28 | |

| c-Myc | CRD-BP (1) | Stability ↑ | 22–27 | |

| c-fos | Unr | Stability ↓ | 33 | |

| PAI-2 | Unknown 50-kDa RBP | Stability ↓ | 35 | |

| MnSOD | Unknown RBP | Stability ↓ | 34 | |

| VEGF | Unknown RBP | ?? (2) | 36 | |

| CR-binding miRNAs | p16 | miR-24 | ↓ (3) | 37 |

| HuR | miR-519 | ↓ | 43 | |

| Dicer | Let-7 | ↓ | 38 | |

| Nanog | miR-296, miR-470 | ↓ | 40 | |

| Oct4 | miR-470 | ↓ | 40 | |

| Sox2 | miR-134 | ↓ | 40 | |

| Hoxa9 | miR-126 | ↓ | 41 | |

| Dnmt3b | miR-148 | ↓ | 42 | |

| ZNFs | miR-181a | ↓ | 44 |

Examples of RBPs and microRNAs that interact with the CR. Mammalian mRNAs regulated via changes in stability and translation through CR sequences. Columns list factors interacting with the CR (RBPs, microRNAs), the target mRNAs regulated via CR elements, the RBPs/microRNAs involved, the effect on expression the mRNA, and relevant references. (1) CRD-BP is also named IMP-1 and IGF2BP1; (2) reduction is likely due to lowered mRNA stability; (3) all microRNAs reduced expression of targets by diminished mRNA stability and/or translation.

CR-interacting RBPs

CRD-BP.

Despite the overall scarcity of CR cis-elements described in mammalian mRNAs, the first such sequence was actually described almost two decades ago by the Ross laboratory.22 A 182-nt segment within the c-myc CR, the coding region determinant (CRD), strongly increased the half-life of the c-myc mRNA. The CRD-BP was later identified as a protein with four K homology (KH) domains which enhanced c-myc mRNA stability by protecting the transcript from endonucleolytic attack; other names of CRD-BP include IGF-II mRNA-binding protein (IMP-1, IMP-2, IMP-3) and zip code-binding protein (ZBP1).23–27 To stabilize the c-myc mRNA, CRD-BP requires additional factors, including hnRNP I, Syncrip, YBX1R and DHX9.27 Recently, CRD-BP was also reported to bind to the CR of the β-TrCP mRNA and stabilized it, thereby increasing the abundance of the encoded protein, β-TrCP. In colon cancer cells responding to β-catenin signaling, CRD-BP promoted the expression of both c-myc and β-TrCP, leading to the activation of NFκB and the inhibition of apoptosis.28

FMRP.

The fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) has important developmental roles and is encoded by FMR1, a gene whose mutation is linked to the fragile X mental retardation syndrome.29 FMRP binds the CR of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA and represses APP mRNA translation in response to the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist DHPG (dihydroxyphenylglycol).30 The inhibition of APP expression appears to be due, at least in part, to the FMRP-mediated recruitment of APP mRNA to processing bodies (PBs), specialized sites of mRNA degradation and translational repression.31

hnRNP C.

We recently reported that hnRNP C bound to the APP mRNA CR, causing an enhancement in APP translation.31 This function was explained, at least in part, by the competition between hnRNP C and FMRP for binding to the same RNA segment within the APP CR. According to the proposed model,31 these two RBPs regulate APP mRNA translation competitively: FMRP suppresses APP translation by recruiting APP mRNA into PBs, while hnRNP C enhances APP translation by competing with FMRP binding and hence blocking the localization of APP mRNA in PBs.

Unr.

This cold-shock domain (CSD)-containing RBP, previously implicated in IRES function,32 was shown to bind to the major CR determinant of instability (mCRD) within the c-fos mRNA. By interacting with the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), Unr promoted the translation-coupled decay of c-fos mRNA.33

Unknown CR-binding RBPs.

The manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) mRNA has a CR determinant that confers stability to the transcript.34 Similarly, the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 (PAI-2) mRNA has stability elements within the CR that prevent its degradation by interacting with an as-yet-unknown 50- to 52-kDa RBP.35 The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA also has a regulatory region within the CR which affects mRNA stability, but the RBP(s) involved remains to be identified.36

CR-interacting microRNAs

The past few years have also seen a rising number of examples of microRNAs that target sequences within the mRNA CR. For example, the CR of p16 mRNA, which encodes an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, was shown to be the target of miR-24, which primarily repressed its translation.37 Likewise, let-7 interacted with the CR of the Dicer mRNA and suppressed expression of Dicer, a critical RNase implicated in microRNA biogenesis.38,39 Expression of differentiation factors Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 was similarly repressed through the association of microRNAs miR-296, miR-470 and miR-134 with the corresponding CRs.40 MicroRNAs targeting the CRs of mRNAs encoding the homeobox protein Hoxa9, the zinc finger protein ZNF, the methyltransferase DNMT3B and the RBP HuR (miR-126, miR-181a, miR-148 and miR-519, respectively) similarly repressed the biosynthesis of the encoded proteins.41–44

Progress in the identification of CR-directed microRNAs has been hampered by the exclusion of CR sequences from the databases accessed by microRNA prediction algorithms (e.g., TargetScan, PicTar, miRBase, etc.). However, recent transcriptome-wide sequencing analyses have revealed that CRs likely harbor numerous microRNA sites. For example, HITS-CLIP analysis by the Darnell laboratory showed that 25% of associations between Ago protein and mRNAs were in the CR,45 although the putative microRNA-mRNA interactions at these CR sites await individual study.

Conclusion

For two decades, there were only anecdotal examples of CR cis-elements affecting the mRNA's post-transcriptional fate. With the recent discovery that numerous microRNAs function through CR sequences, there has been a surge in interest in regulatory elements present within the CR. The increased access to high-throughput, transcriptome-wide sequencing technologies, as well as the inclusion of CR sequences in microRNA-mRNA prediction algorithms will be especially important to propel progress.

A greater appreciation of CR-acting microRNAs will consequently rise the recognition of CR-acting RBPs. Indeed, RBPs and RISC-microRNAs share an affinity for mature mRNAs, both rely on the same cellular machineries to repress or increase gene expression (PBs, ribosomes, ribonucleases, etc.,), and in several instances, they have important functional interactions, sometimes cooperative or competitive.15,16

It remains to be determined whether CR-directed microRNAs/RBPs interact with mRNAs engaged in transport, with mRNAs present in specialized cytoplasmic domains, or with translating mRNAs sparsely occupied with ribosomes. The increased availability of technologies that identify exact RBP/microRNA binding sites and ribosome occupancy, will allow these important questions to be addressed in depth. With renewed appreciation that CRs encode key information on mRNA turnover and translation, the stage is ready to incorporate CR-interacting factors into the increasingly rich constellation of regulators of mammalian gene expression programs.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging-Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CR

coding region

- RBP

RNA-binding protein

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- 1.Mitchell P, Tollervey D. mRNA stability in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orphanides G, Reinberg D. A unified theory of gene expression. Cell. 2002;108:439–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore MJ. From birth to death: the complex lives of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science. 2005;309:1514–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1111443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: implications for cellular senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:243–255. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1977–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickering BM, Willis AE. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilusz CJ, Wormington M, Peltz SW. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ørom UA, Nielsen FC, Lund AH. MicroRNA-10a binds the 5′UTR of ribosomal protein mRNAs and enhances their translation. Mol Cell. 2008;30:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marasa BS, Srikantan S, Masuda K, Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Yang X, et al. Increased MKK4 abundance with replicative senescence is linked to the joint reduction of multiple microRNAs. Sci Signal. 2009;2:69. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henke JI, Goergen D, Zheng J, Song Y, Schüttler CG, Fehr C, et al. microRNA-122 stimulates translation of hepatitis C virus RNA. EMBO J. 2008;27:3300–3310. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal A, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Kawai T, Yang X, Martindale JL, Gorospe M. Concurrent versus individual binding of HuR and AUF1 to common labile target mRNAs. EMBO J. 2004;23:3092–3102. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao B, Hu Y, Brewer G. Competitive binding of AUF1 and TIAR to MYC mRNA controls its translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:511–518. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HH, Kuwano Y, Srikantan S, Lee EK, Martindale JL, Gorospe M. HuR recruits let-7/RISC to repress c-Myc expression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1743–1748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1812509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkie GS, Dickson KS, Gray NK. Regulation of mRNA translation by 5′- and 3′-UTR-binding factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:182–188. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlasova IA, Bohjanen PR. Posttranscriptional regulation of gene networks by GU-rich elements and CELF proteins. RNA Biol. 2008;5:201–207. doi: 10.4161/rna.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barreau C, Paillard L, Osborne HB. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikulits W, Pradet-Balade B, Habermann B, Beug H, Garcia-Sanz JA, Müllner EW. Isolation of translationally controlled mRNAs by differential screening. FASEB J. 2000;14:1641–1652. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.11.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein PL, Herrick DJ, Prokipcak RD, Ross J. Control of c-myc mRNA half-life in vitro by a protein capable of binding to a coding region stability determinant. Genes Dev. 1992;6:642–654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisdom R, Lee W. The protein-coding region of c-myc mRNA contains a sequence that specifies rapid mRNA turnover and induction by protein synthesis inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1991;5:232–243. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrick DJ, Ross J. The half-life of c-myc mRNA in growing and serum-stimulated cells: influence of the coding and 3′ untranslated regions and role of ribosome translocation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2119–2128. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeilding NM, Procopio WN, Rehman MT, Lee WM. c-myc mRNA is downregulated during myogenic differentiation by accelerated decay that depends on translation of regulatory coding elements. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15749–15757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle GA, Betz NA, Leeds PF, Fleisig AJ, Prokipcak RD, Ross J. The c-myc coding region determinant-binding protein: a member of a family of KH domain RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5036–5044. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weidensdorfer D, Stöhr N, Baude A, Lederer M, Köhn M, Schierhorn A, et al. Control of c-myc mRNA stability by IGF2BP1-associated cytoplasmic RNPs. RNA. 2009;15:104–115. doi: 10.1261/rna.1175909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noubissi FK, Elcheva I, Bhatia N, Shakoori A, Ougolkov A, Liu J, et al. CRD-BP mediates stabilization of betaTrCP1 and c-myc mRNA in response to beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2006;441:898–901. doi: 10.1038/nature04839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Till SM. The developmental roles of FMRP. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:507–510. doi: 10.1042/BST0380507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westmark CJ, Malter JS. FMRP mediates mGluR5-dependent translation of amyloid precursor protein. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee EK, Kim HH, Kuwano Y, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Subaran SS, et al. hnRNP C promotes APP translation by competing with FMRP for APP mRNA recruitment to P bodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:732–739. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt SL, Hsuan JJ, Totty N, Jackson RJ. unr, a cellular cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with five coldshock domains, is required for internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA. Genes Dev. 1999;15:437–438. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang TC, Yamashita A, Chen CY, Yamashita Y, Zhu W, Durdan S, et al. UNR, a new partner of poly(A)-binding protein, plays a key role in translationally coupled mRNA turnover mediated by the c-fos major coding-region determinant. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2010–2023. doi: 10.1101/gad.1219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis CA, Monnier JM, Nick HS. A coding region determinant of instability regulates levels of manganese superoxide dismutase mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37317–37326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tierney MJ, Medcalf RL. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 contains mRNA instability elements within exon 4 of the coding region. Sequence homology to coding region instability determinants in other mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13675–13684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dibbens JA, Miller DL, Damert A, Risau W, Vadas MA, Goodall GJ. Hypoxic regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA stability requires the cooperation of multiple RNA elements. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:907–919. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lal A, Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Pullmann R, Jr, Srikantan S, et al. p16(INK4a) translation suppressed by miR-24. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:1864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14879–14884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forman JJ, Coller HA. The code within the code: microRNAs target coding regions. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1533–1541. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen WF, Hu YL, Uttarwar L, Passegue E, Largman C. MicroRNA-126 regulates HOXA9 by binding to the homeobox. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4609–4619. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01652-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duursma AM, Kedde M, Schrier M, le Sage C, Agami R. miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. RNA. 2008;14:872–877. doi: 10.1261/rna.972008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Kuwano Y, Gorospe M. miR-519 reduces cell proliferation by lowering RNA-binding protein HuR levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20297–20302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809376106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang S, Wu S, Ding J, Lin J, Wei L, Gu J, et al. MicroRNA-181a modulates gene expression of zinc finger family members by directly targeting their coding regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7211–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]